Abstract

Osteogenic cells respond to mechanical changes in their environment by altering their spread area, morphology, and gene expression profile. In particular, the bulk modulus of the substrate, as well as its microstructure and thickness, can substantially alter the local stiffness experienced by the cell. Although bone tissue regeneration strategies involve culture of bone cells on various biomaterial scaffolds, which are often cross-linked to enhance their physical integrity, it is difficult to ascertain and compare the local stiffness experienced by cells cultured on different biomaterials. In this study, we seek to characterize the local stiffness at the cellular level for MC3T3-E1 cells plated on biomaterial substrates of varying modulus, thickness, and cross-linking concentration. Cells were cultured on flat and wedge-shaped gels made from polyacrylamide or cross-linked collagen. The cross-linking density of the collagen gels was varied to investigate the effect of fiber cross-linking in conjunction with substrate thickness. Cell spread area was used as a measure of osteogenic differentiation. Finite element simulations were used to examine the effects of fiber cross-linking and substrate thickness on the resistance of the gel to cellular forces, corresponding to the equivalent shear stiffness for the gel structure in the region directly surrounding the cell. The results of this study show that MC3T3 cells cultured on a soft fibrous substrate attain the same spread cell area as those cultured on a much higher modulus, but nonfibrous substrate. Finite element simulations predict that a dramatic increase in the equivalent shear stiffness of fibrous collagen gels occurs as cross-linking density is increased, with equivalent stiffness also increasing as gel thickness is decreased. These results provide an insight into the response of osteogenic cells to individual substrate parameters and have the potential to inform future bone tissue regeneration strategies that can optimize the equivalent stiffness experienced by a cell.

Introduction

Osteogenic cells possess a highly developed cytoskeleton (1,2), and have been long regarded as efficacious mechanosensors (3,4). There has been widespread investigation into the effect of various mechanical forces, including substrate stiffness (5,6), fluid flow-induced shear stress (7), and applied substrate strain (8) on osteogenic cell behavior. Although a general consensus exists that an understanding of mechanotransduction is necessary for the treatment of disease originating at the cellular level and the development of tissue engineering strategies (2,9,10), the exact nature of the methods by which cells interact with their environment must be delineated if the mechanotransduction of osteogenic cells is to be better understood. Specifically, the combined effects of bulk material modulus, substrate thickness, and the microstructure of the substrate have yet to be investigated.

One of the most common methods of investigating mechanotransduction is the culture of cells on substrates of controllable modulus and it has been shown that a change in substrate modulus can affect osteoblast behavior, including proliferation, migration, and differentiation (11–13). There are various approaches for altering the modulus of substrate materials for in vitro cell culture applications. Collagen, the primary component of the matrix on which bone cells develop, can be modified using a variety of cross-linking methods including chemical cross-linkers, such as glutaraldehyde and 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDAC), as well as exposure to ultraviolet light to achieve a specific bulk substrate modulus (14,15). Polyacrylamide (PA) is widely used in mechanotransduction studies due to the relative ease and reliability with which its modulus can be altered, specifically by varying the percentage of acrylamide and bis-acrylamide used in the polymerization process (16,17). A range of other polymers including polydimethylsiloxane (13), polyethylene glycol (18), and polymethyl methacrylate (19) have also been used as substrates of controllable modulus.

Recently, substrate thickness has been used as a method of varying the stiffness experienced by the cell (20,21). The structural stiffness experienced by the cell is affected by both the substrate geometry, most notably the distance to the substrate boundaries (21), and the substrate modulus, an intrinsic property of the substrate material. On thin substrates (<5 μm) cell-induced contractility forces can propagate through the entirety of the substrate allowing the mechanical properties of the underlying material, often glass coverslips or tissue culture plastic, to influence cell behavior. However, the effect of substrate thickness is also governed by the structure of the substrate in question. Specifically, it has been demonstrated that cell-induced stresses travel only a few microns through linear, homogenous substrates, such as PA (22), whereas cells on fibrous substrates have been shown to be influenced by structures that are hundreds of microns away (20,23); for example, underlying rigid coverslips have been shown to influence cell spreading and morphology on fibrous substrates of up to 130 μm thick (24). The enhanced propagation of mechanical signals has been attributed to the fibrous nature of biological substrates; specifically, it has been proposed that cell-induced forces propagate through individual fibers over long distances (24,25).

The specific effect of fibers on the mechanical properties of fibrous gels has been investigated through computational approaches. A microscale discrete fiber representative element has been linked to a Galerkin macroscale model to study the effects of fibrosity on bulk collagen gel properties (26). This method has been further developed to investigate both fibrous wound behavior (27) and the response of cells to gel fibrosity (24). However, this approach prevents fibers from extending across elements at the macroscopic level. In the relatively thin (70 μm) substrates used in typical cell mechanotransduction experiments (21), collagen fibers may extend through the entire gel thickness.

The range of methods used to alter substrate stiffness experienced by the cell has led to apparent contradictions regarding the response of osteoblastic cells to their local mechanical environment. For example, osteoblast differentiation has been shown to occur on collagen-coated polymer substrates between 20 and 40 kPa (5,18). Meanwhile, our own previous work has shown that osteoblast differentiation occurs on type 1 collagen substrates of 1 kPa, whereas softer substrates of 300 Pa induce osteoblast differentiation followed by early osteocyte differentiation. Such discrepancies are likely explained by the fact that the bulk modulus of the substrate is usually reported, whereas the precise stiffness experienced by the cell, here termed the equivalent stiffness, is dictated by the material modulus, substrate thickness, and substrate microstructure, which can all vary dramatically depending on the biomaterial fabrication processes (e.g., cross-linking). However, it is difficult to ascertain the equivalent stiffness experienced by the cell and as such it is not yet known precisely how each property contributes to the local mechanical stimulation of osteogenic cells. The field of bone tissue engineering has thus far relied primarily on measurement of bulk material properties to ascertain the effect of extracellular mechanical cues imparted by biomaterial scaffolds on cell differentiation. However, the effects of other extracellular matrix properties such as size and microstructure cannot be ignored and must be investigated in greater detail if the efficacy of various biomaterials in osteogenic differentiation is to be understood.

The objective of this study is to derive an understanding of the individual and combined effects of substrate modulus, fibrosity, thickness, and cross-linking density on the local stiffness experienced by osteoblastic cells. MC3T3-E1 cells were cultured on flat and wedge-shaped nonfibrous PA and fibrous collagen gels, while cell spread area and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity were used as early indicators of cell differentiation. Cross-linked collagen gels (of varied cross-linking density) were then used to determine the effect of fiber cross-linking in conjunction with substrate thickness on the differentiation of osteogenic cells. Finite element (FE) models were generated to represent the contraction of an osteoblastic cell on a soft linearly elastic gel with discrete tensile collagen fibers. These models were used to investigate the transfer of force through collagen gels of different cross-linking density over a range of gel thicknesses. We hypothesize that the equivalent stiffness as experienced by the cell is influenced by gel bulk stiffness, thickness, and cross-linking density and that these factors must be accounted for when investigating mechanotransduction in vitro.

Materials and Methods

Experimental methods

Substrate manufacture

Flat and wedge-shaped collagen gels were prepared as described previously (6). Briefly, rat tail type 1 collagen (Sigma-Aldrich, St-Louis, MO) was neutralized using 10 mM NaOH, and diluted to 4 mg/mL with dH2O. Glass slides were activated by sonicating in 1% 3-aminopropyltrimethoxy silane (Sigma-Aldrich) before being incubated in 0.5% glutaraldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) overnight. The mixture was pipetted onto the activated glass slides (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) while a coverslide, treated with Sigmacote (Sigma-Aldrich), was placed over the gel to allow the gel to set without adhering to the coverslide. Wedge-shaped gels were constructed by placing a 150 μm coverslip on one side of the glass slide, forming a wedge-shaped mold within which the gel was set, as shown in Fig. 1 A. Following gel formation the top coverslip was removed leaving the wedge-shaped gel as shown in Fig. 1 B. Flat gels were formed at ∼70 μm thick, whereas wedge-shaped gels ranged from 0 to 150 μm over a lateral distance of 50 mm. The modulus of collagen gels was controlled through chemical cross-linking with 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDAC)/N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (NHS) (both Sigma Aldrich), resulting in the formation of zero length cross-links between fibers. Formed gels were treated with 0, 20, 50, 100, or 150 mM EDAC/mg collagen at a 9:2 ratio of EDAC/NHS. The moduli of EDAC cross-linked collagen gels have been measured in our previous work as ranging between 0.01 (0 mM/mg) and 1 kPa (150 mM/mg) (6).

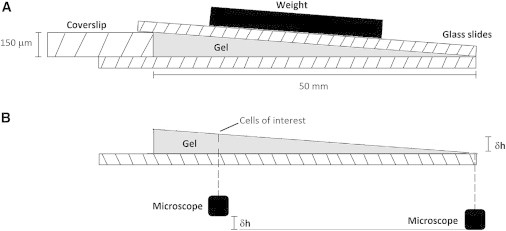

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic showing wedge-shaped gel formation. Gels ranged from a height of 0 to 150 μm across a horizontal distance of 50 mm. (B) Gel height was confirmed by recording the change in the vertical position of the microscope relative to the stage required to focus on the top surface of the gel.

PA gels were formed by varying the concentrations of acrylamide and bis-acrylamide to alter the gel stiffness as described previously (17), before being polymerized with 0.15% TEMED (Sigma Aldrich). Flat and wedge-shaped PA gels were formed between treated glass coverslips as described previously. SulfoSANPAH (Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA), a heterobifunctional cross-linker was diluted to 1 mg/mL in HEPES buffer and used to bind acetic acid diluted collagen (2 mg/mL) to the gel surface to allow for cell attachment (28). Bulk gel moduli of similar PA gels were ascertained from previous studies showing a range of moduli from 0.6 to 153 kPa (17).

Cell culture

MC3T3-E1 cells, an immortalized preosteoblast cell line were maintained in Alpha Modified Eagle’s Medium (α-MEM) containing 100 ug/mL L-glutamine and supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 units/mL Antibacterial-Antimytotic (all Sigma Aldrich). All experiments were conducted at passage 4. Cells were cultured on flat and wedge-shaped gels of either PA or collagen for 24 h at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. Membrane permeabilization was conducted with 0.1% Triton in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (both Sigma Aldrich) and cells were stained with Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled rhodamine-phalloidin (to stain the actin cytoskeleton) and Hoechst (to stain cell nuclei) (both BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Cells examined for ALP activity were cultured for 7 days before being lysed.

Cell imaging

Cells were imaged using a Leica DM2700 inverted microscope (Wetzlar, Germany) at 10× magnification and the average cell spread area was quantified as a measure of osteogenic differentiation. Gel height at each location was verified by first focusing on the top surface of the glass slide, and then recording the vertical movement of the microscope stage required to focus on the cells of interest. This is further illustrated in Fig. 1 B.

Osteogenic assays

Cells were lysed using Cellytic M with 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (both Sigma Aldrich). ALP activity was quantified using a colorimetric assay (Sigma Aldrich) as described previously (6,29). Results were then normalized to the DNA content of each well.

FE methods

Substrate model generation

The materials under study are a type 1 collagen gel, the microstructure of which may be varied by chemical cross-linking, allowing a greater number of adjacent fibers to form zero length molecular bonds with one another, thus affecting the material's mechanical properties (30). To understand the role of microstructural cross-linking density on the mechanical response of these gels, a micromechanical model was developed using ABAQUS FE software (Dassault Systemes, Vélizy-Villacoublay, France), representing the fibrous and nonfibrous phases of this material discretely within an FE framework. This approach was used to predict the effective properties of random collagen fiber distributions, with a range of cross-linking densities to study their effect on macroscopic material behavior.

The fibers within collagen gels exhibit no preferential orientation and can therefore be considered to be randomly oriented. They measure ∼200 nm (31) in diameter and account for ∼20% of the material volume fraction (32,33). A numerical algorithm was developed to create representative distributions of these fibrous gels in two dimensions, whereby each fiber was assigned a center point, C, which was randomly chosen within a domain measuring 450 × 450 μm. The orientation of each fiber was also chosen to be a random angle θ, where −π ≥ θ > π. The fiber end points were then generated by extrapolating half the length (chosen randomly between the limits 10 and 500 μm) in the direction of the angle θ and its opposite angle θ-180. Fibers were then truncated so as to fall within the confines of the gel as appropriate. For the resulting collagen fiber distribution generated using this procedure see Fig. 2 B. Models were generated for a range of cross-linking densities with cross-linked and noncross-linked fibers being introduced to the model separately. Briefly, for each model, the relevant cross-linked fibers were imported to the ABAQUS sketch facility as a single part through a Python script. This created a series of fibers where each intersecting point was assigned a unique node, whereas a single element joined corresponding nodes to one another. Noncross-linked fibers were introduced as discrete nodes and elements to the relevant Abaqus input file, with a single element spanning the entire length of each fiber. Thus, noncross-linked fibers were prevented from directly interacting with one another, although indirect interaction between noncross-linked fibers could still occur through the gel. This process was repeated for five different fiber permutations in order to minimize the effects of individual fiber location variation on the results.

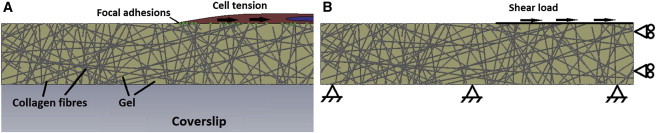

Figure 2.

(A) Schematic of an MC3T3-E1 cell applying force to a fibrous substrate. The force applied by the cell is transferred through the focal adhesion complexes and resisted by the gel. (B) Boundary conditions placed on micromechanics model. A shear load of 1 N was applied to the nodes to simulate the forces exerted by the cell at the cell-substrate interface. To see this figure in color, go online.

Material model

Plane stress FE models were created to simulate a 100 μm wide section of a soft gel containing relatively stiff collagen fibers. Fibers were set as linear, tension only, truss elements (T2D2) with a circular cross section of radius 100 nm, and embedded into the plane stress element (CPS8R) gel region. A Young’s modulus of 10 Pa was assigned to the gel based on previous atomic force microscopy measurements (6). A Young’s modulus of 2 MPa was assigned to the fibers to achieve a range of equivalent stiffness on the same scale as the range present in the PA substrates investigated.

Loading and boundary conditions to simulate cell contraction

Fig. 2 A shows a representation of a single cell interacting with the collagen fibers within an infinitely stiff and thick gel, situated on a glass slide. The cell interacts with the substrate through focal adhesion complexes, and can induce a contractile force on the gel. The resistance of the gel to this force, termed equivalent shear stiffness in this study, is interpreted by the cell and the force induced by the cell is altered until homeostasis is achieved. Fig. 2 B is the FE approximation applied in this study to simulate the interaction between a contracting cell and a fibrous gel on a glass slide. The cell is not discretely modeled, but is represented by a nominal shear load of 1 N, acting at the edges of fibers, based on recent measurements for the dimensions of MC3T3-E1 cells on collagen gels (34). A no-slip boundary condition is used to simulate the rigid coverslip under the gel, whereas a free-slip boundary condition is used where symmetry exists to improve model efficiency. The horizontal movement of the nodes is used as a measure of the equivalent shear stiffness of the gel structure in response to the applied load.

Statistical methods

A two-way analysis of variance was conducted to determine statistical significance in both the experimental and computational results.

Results

Experimental results

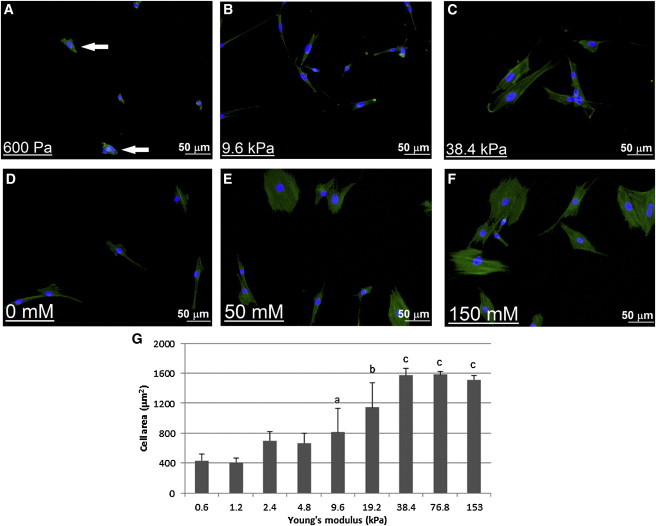

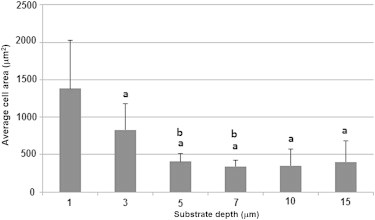

On flat gels of 0.6 or 1.2 kPa, cells adopt an encapsulated morphology and converge into groups as shown in Fig. 3 A. The average cell spread area on these substrates is 400 μm2. Above this stiffness cells separate from one another and begin to elongate, increasing their area to between 700 and 800 μm2 on substrates of between 2.4 and 9.6 kPa (see Fig. 3 G). The cells do not group together on these substrates as shown by the dispersed nature of the cells in Fig. 3 B. On stiffer substrates (19.6 kPa and above), cells increase their area to an average of between 1200 and 1600 μm2 and adopt the spread morphology associated with osteoblasts, see Fig. 3 C. It was also observed that the cells exhibited a larger area on thin PA gels, with cells cultured on a wedge-shaped 1.2 kPa gel having an average area of 1380 ± 644 μm2 and 830 ± 341 μm2 on a 1 and 3 μm thick section of the gel, respectively. However, as shown in Fig. 4, gel depth had no effect on cell area above 5 μm.

Figure 3.

Representative images of MC3T3-E1 cells on polyacrylamide gels of (A) 600 Pa, (B) 9.6 kPa, and (C) 38.4 kPa and collagen gels cross-linked with (D) 0 mM EDAC, (E) 50 mM EDAC, and (F) 150 mM EDAC. White arrows on (A) indicate multiple cells grouped together; and (G) cell spread area of MC3T3-E1 cells cultured on polyacrylamide gels of ∼70 μm. (a) Indicates statistically higher than 0.6 kPa to 4.8 kPa gels. (b) Indicates statistically higher than 0.6 kPa to 9.6 kPa gels. (c) Indicates statistically higher than 0.6 kPa to 19.2 kPa gels. p < 0.05. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 4.

Cell spread area of MC3T3-E1 cells cultured on wedge-shaped soft (1.2 kPa) polyacrylamide gels of various thicknesses. (a) Indicates statistically difference to cells cultured on 1 μm thick gel. (b) Indicates statistical difference to cells cultured on 3 μm thick gel. p < 0.05.

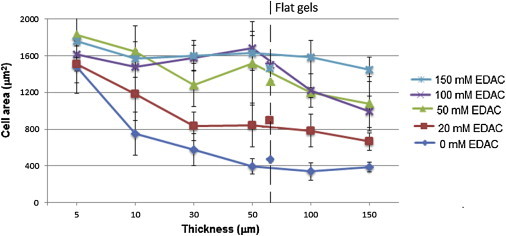

Cell area on cross-linked collagen substrates increased as the cross-linking density was increased. As shown in Fig. 3 G, the lowest average spread area is 478 ± 214 μm2, which occurred on the noncross-linked gel (shown in Fig. 3 D), where the cells typically display an elongated morphology, similar to that observed on the 9.6 kPa PA gel, shown in Fig. 3 B. On gels with a higher density of cross-linking (50 to 150 mM/mg collagen (Fig. 3, E and F), the cells adopt the spread morphology as observed on 38.4 kPa PA gels, shown in Fig. 3 C, while the average spread cell area increases to between 1200 and 1600 μm2. Cell spread area was also shown to increase as the gel thickness was decreased, and this effect was more pronounced on gels with a low cross linking density. As shown in Fig. 5, a large rise in cell area, from 389 ± 54 μm2 to 1478 ± 283 μm2 was observed as the thickness of a noncross-linked collagen gel was decreased from 150 to 5 μm. On more densely cross-linked gels (50 to 150 mM EDAC), the thickness of the structure had less effect on the spread cell area. This is also shown in Fig. 5, where the average cell spread area on 150 mM EDAC-cross-linked gels increases from 1451 ± 132 μm2 to 1761 ± 247 μm2.

Figure 5.

Cell area (μm2) of MC3T3-E1 cells cultured on wedge-shaped crosslinked collagen substrates. The average cell area at relevant thickness for each gel is presented. The average cell area on flat gels (∼70 μm thick) is represented by the respective markers for each concentration of crosslinking agent. To see this figure in color, go online.

As shown in Fig. 6 A, similar levels of ALP activity were recorded in cells cultured on all collagen gels, with levels of between 1.4 ± 0.18 mM/ng DNA and 1.7 ± 0.14 mM/ng DNA. In cells cultured on PA gels, the highest levels of ALP activity (between 1.04 and 1.16 mM/ng DNA) were found in cells cultured on gels with a stiffness < 19.6 kPa (see Fig. 6 B). Cells cultured on softer gels exhibited lower levels of ALP activity of between 0.04 and 0.4 mM/ng DNA.

Figure 6.

ALP activity normalized to DNA content measured in cells cultured on (A) collagen gels and (B) polyacrylamide gels, for 7 days. (a) Indicates significantly higher activity than cells cultured on PA gels of 4.8 kPa and below. (b) Indicates significantly higher activity than cells cultured on PA gels of 9.6 kPa and below. p < 0.05.

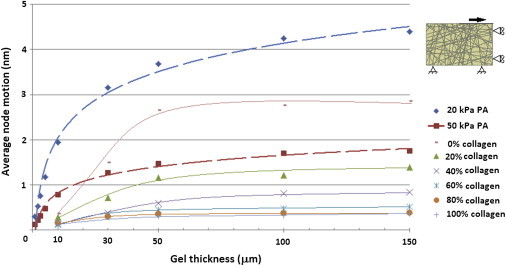

FE results

Fig. 7 shows the average horizontal motion of the nodes subjected to a 1 N load (representing cell contraction) for both the fibrous gel models and nonfibrous gels of various Young’s moduli. The motion of these nodes was used as an indicator of the equivalent shear stiffness of the substrates. The equivalent stiffness of nonfibrous PA gels decreased linearly as gel modulus was increased. It was also seen that a logarithmic increase in equivalent stiffness occurred as gel thickness was reduced, with the motion recorded in a 10 kPa gel reduced from 0.88 nm in a 150 μm to 0.6 pm in a 1 μm gel. It was observed that the introduction of fibers to the gel greatly increased the equivalent stiffness of the substrates, with fibrous gels showing similar levels of motion to nonfibrous gels with Young’s moduli of between 5 and 20 kPa. For fibrous gels, the motion of the nodes decreased from 2.86 to 0.36 nm as the percentage of cross-linked fibers was increased from 0% to 100% in a 150 μm gel, indicating an increase in the equivalent stiffness. A decrease in gel thickness also increased the equivalent stiffness of the gels, although this effect was stronger in gels with a lower percentage of cross-linked fibers. This can be seen most clearly in Fig. 7 where the motion observed in the noncross-linked gel decreases from 2.86 to 0.42 nm as the gel thickness is decreased from 150 to 10 μm, whereas the fully cross-linked gel experiences a decrease in motion from 0.36 to 0.21 nm over the same decrease in thickness.

Figure 7.

Equivalent shear stiffness of nonfibrous polyacrylamide and fibrous cross-linked collagen gels of different thicknesses as calculated using ABAQUS software. To see this figure in color, go online.

The motion experienced by these nodes in a fully cross-linked gel ranges from 0.21 nm at a depth of 10 μm, to 0.36 nm at a depth of 150 μm. This is similar to the level of motion experienced in a nonfibrous gel of 20 kPa. As the percentage of cross-linked fibers in the gel is decreased, the motion undergone by these nodes increased to as high as 2.8 nm for a gel containing no cross-links between fibers at a depth of 150 μm.

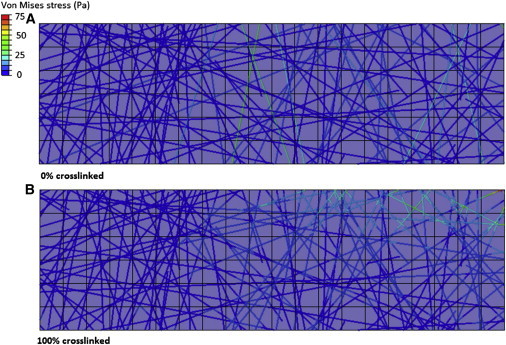

Fig. 8 shows the transfer of force through the fibrous gel in the noncross-linked and fully cross-linked configurations. It can be observed that in the noncross-linked gel force is borne mainly by the fibers which extend through the entire gel depth, whereas in the fully cross-linked gel force is transferred between fibers and so a greater percentage of fibers become involved in the mechanical resistance of the gel.

Figure 8.

Force is transferred mainly through the fibers, which span the entire gel depth in a noncross-linked fibrous gel (A), whereas force is transferred through multiple adjoined fibers in a fully cross-linked gel (B). To see this figure in color, go online.

Discussion

Cell spread area has been previously been shown to be an indicator of the differentiation stage of mesenchymal stem cells, with osteoblast differentiation found to correlate with increased cell area (35,36). Meanwhile, ALP activity is widely known as a key aspect of osteogenic differentiation (37,38). The results of this study show that cells on nonfibrous PA gels exhibited a larger spread cell area (>1600 μm2) on stiffer gels (E > 38 kPa). It was also shown that cells cultured on soft (Young’s modulus < 300 Pa) fibrous collagen substrates exhibit the same large spread area (1200–1600 μm2) as those cultured on stiff (E > 38 kPa) PA gels. Moreover, as the concentration of cross-linking agent used in these fibrous gels was increased, the cell spread area also increased. The FE studies conducted here predict that the equivalent shear stiffness of a fiber-reinforced soft gel is significantly greater than that of a nonfibrous gel. It was also shown that, at high cross-linking concentrations (100% of fibers cross-linked), the effective stiffness experienced by the cells approached that experienced by cells on much stiffer nonfibrous substrates. These results provide an insight into why cell spread area on cross-linked collagen gels, which are very soft (<1 kPa) when measured through nanoindentation, is akin to that of cells cultured on much stiffer nonfibrous gels. Gel thickness was also shown to have an effect on both cell spread area and effective stiffness. Experimental results showed that thinner substrates resulted in an increase in cell spread area, whereas the computational simulations revealed that such results could be related to an increase in effective stiffness as gel thickness was reduced. However, it was noted that effect of gel thickness was less for cells plated on highly cross-linked collagen gels.

A possible limitation of this study is the use of the MC3T3-E1 cell line as a model of primary osteoblasts. However, these cells have been shown to be a suitable model for several aspects of osteoblast behavior, including ALP activity and matrix mineralization (37,39), while they have also been used to investigate cell spread area in response to substrate stiffness (40).

The effects of substrate modulus and thickness on cell behavior have both been studied in detail previously (5,21,24). However, the interplay between the various factors, i.e., bulk modulus, thickness, and in particular material microstructure, has yet to be elucidated. The results presented in this study provide an insight into bone cell behavior and provide a possible explanation for previous contradictions concerning the differentiation of osteogenic cells in response to extracellular matrix stiffness (5,18,41). Specifically, it has been shown that the combined effects of substrate modulus, thickness, and microstructure must be taken into account to determine the mechanical forces experienced at the cellular level.

Gel cross-linking has been a widely used method of altering the stiffness of substrates and scaffolds used in in vitro experiments (6,14,30). An advantage of the method is that the surface chemistry can remain constant while the mechanical properties of the gel are altered. However, as of yet the interaction between gel cross-linking and the thickness of the substrate has not been investigated. In this study, it is shown that a highly cross-linked collagen gel can reduce the effect of gel thickness on cell area. Gel thickness has also been shown to affect cell behavior to different extents depending on the nature of the gel material, with cells on fibrous materials being influenced by gel thicknesses of up to over 130 μm (20), whereas cells on nonfibrous materials are only influenced by structures within 5–10 μm of the cell (21,22). The results of this study further illustrate that the effect of gel thickness on cell area is dependent on the microstructure of the gel, specifically the presence of discrete fibers and the interaction present between those fibers (cross-linking density).

To understand the mechanisms behind this behavior the results of the FE micromechanical simulations presented here must be considered. These simulations show that the effective shear stiffness, a measure of the stiffness as experienced by the cell, of a nonfibrous gel was increased as the gel thickness is decreased. This is because in a thin gel, the stiffness as experienced by the cell is dominated by the comparatively stiff underlying coverslip (21,22). The models also showed that in fibrous gels, such as the collagen gels investigated in this study, contractile forces from the cell were predominantly transferred through the fibers rather than through the remainder of the gel. Specifically, it was shown that fibers that spanned the entire depth of the gel transferred the majority of the force. This provides an explanation for the increase in cell spread area on thinner collagen gels, due to a larger number of fibers extending through the entire depth of a thinner gel. It was also shown that there was a very slight increase in equivalent stiffness as the gels became thinner when all of the fibers in the gel were joined through cross-links, which corresponds to the reduced effect of gel thickness on cell spread area on highly cross-linked collagen gels. This can be explained by the high level of cross-linking between the fibers, which allows force to be transferred through multiple fibers through the entire gel depth, in a way allowing multiple connected fibers to behave as one larger fiber. This in turn increases the equivalent stiffness of the gels and therefore the spread area of cells cultured on these gels.

These results have important implications for the development of future tissue engineering strategies. Specifically, they demonstrate that the material properties measured through commonly used techniques such as atomic force microscopy (5,42), nanoindentation (43,44), and confined/unconfined compression (45,46) may not reflect the mechanical stimulation experienced at the cellular level. This is of particular significance when investigating fibrous materials, such as those commonly used in bone tissue engineering strategies (14,47,48). The results presented here highlight the fact that greater attention must be paid to the effects of the local mechanical environment (i.e., cellular level) if further advances are to be made in the field of bone tissue engineering.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first time the combined effects of substrate modulus, thickness, and microstructure on cell behavior have been investigated and this study provides an enhanced understanding of the forces actually experienced by osteogenic cells in two-dimensional in vitro experiments. The results presented here show that commonly used methods of substrate modulus measurement cannot accurately interpret the overall stiffness as experienced by the cell. Future studies should consider the substrate modulus, thickness, and micromechanical structure during comparison of cell behavior on different substrates. The findings in this study can improve the current understanding of osteogenic mechanotransduction and pave the way for a more successful transfer of in vitro experimental findings to tissue regeneration strategies.

References

- 1.Tanaka-Kamioka K., Kamioka H., Lim S.-S. Osteocyte shape is dependent on actin filaments and osteocyte processes are unique actin-rich projections. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1998;13:1555–1568. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.10.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonewald L.F. The amazing osteocyte. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011;26:229–238. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kapur S., Baylink D.J., Lau K.H. Fluid flow shear stress stimulates human osteoblast proliferation and differentiation through multiple interacting and competing signal transduction pathways. Bone. 2003;32:241–251. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00979-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.You L., Temiyasathit S., Jacobs C.R. Osteocytes as mechanosensors in the inhibition of bone resorption due to mechanical loading. Bone. 2008;42:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Engler A.J., Sen S., Discher D.E. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mullen C.A., Haugh M.G., McNamara L.M. Osteocyte differentiation is regulated by extracellular matrix stiffness and intercellular separation. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2013;28:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ponik S.M., Triplett J.W., Pavalko F.M. Osteoblasts and osteocytes respond differently to oscillatory and unidirectional fluid flow profiles. J. Cell. Biochem. 2007;100:794–807. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weyts F.A.A., Bosmans B., Weinans H. Mechanical control of human osteoblast apoptosis and proliferation in relation to differentiation. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2003;72:505–512. doi: 10.1007/s00223-002-2027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Papachroni K.K., Karatzas D.N., Papavassiliou A.G. Mechanotransduction in osteoblast regulation and bone disease. Trends Mol. Med. 2009;15:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santos A., Bakker A.D., Klein-Nulend J. The role of osteocytes in bone mechanotransduction. Osteoporos. Int. 2009;20:1027–1031. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0858-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keogh M.B., O’Brien F.J., Daly J.S. Substrate stiffness and contractile behavior modulate the functional maturation of osteoblasts on a collagen-GAG scaffold. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:4305–4313. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsai S.W., Liou H.M., Hsu F.Y. MG63 osteoblast-like cells exhibit different behavior when grown on electrospun collagen matrix versus electrospun gelatin matrix. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e31200. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Evans N.D., Minelli C., Stevens M.M. Substrate stiffness affects early differentiation events in embryonic stem cells. Eur. Cell Mater. 2009;18:1–13. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v018a01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tierney C.M., Haugh M.G., O’Brien F.J. The effects of collagen concentration and cross-link density on the biological, structural and mechanical properties of collagen-GAG scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2009;2:202–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chau D.Y., Collighan R.J., Griffin M. The cellular response to transglutaminase-cross-linked collagen. Biomaterials. 2005;26:6518–6529. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Y.L., Pelham R.J., Jr. Preparation of a flexible, porous polyacrylamide substrate for mechanical studies of cultured cells. In: Richard B.V., editor. Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press; Waltham, MA: 1998. pp. 489–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tse J.R., Engler A.J. Preparation of hydrogel substrates with tunable mechanical properties. In: Bonifacino J.S., Dasso M., Harford J.B., Lippincott-Schwartz J., Yamada K.M., editors. Current Protocols in Cell Biology. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2001. pp. 10.16.1–10.16.16. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khatiwala, C. B., S. R. Peyton, and A. J. Putnam. 2006. Osteogenic differentiation of Mc3t3–E1 cells regulated by substrate stiffness requires Mapk activation. American Institute of Chemical Engineers Annual Meeting, San Francisco, CA.

- 19.Dalby M.J., Gadegaard N., Oreffo R.O.C. The control of human mesenchymal cell differentiation using nanoscale symmetry and disorder. Nat. Mater. 2007;6:997–1003. doi: 10.1038/nmat2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leong W.S., Tay C.Y., Tan L.P. Thickness sensing of hMSCs on collagen gel directs stem cell fate. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;401:287–292. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sen S., Engler A.J., Discher D.E. Matrix strains induced by cells: computing how far cells can feel. Cell Mol Bioeng. 2009;2:39–48. doi: 10.1007/s12195-009-0052-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maloney J.M., Walton E.B., Van Vliet K.J. Influence of finite thickness and stiffness on cellular adhesion-induced deformation of compliant substrata. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 2008;78:041923. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.78.041923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feng C.H., Cheng Y.C., Chao P.H.G. The influence and interactions of substrate thickness, organization and dimensionality on cell morphology and migration. Acta Biomater. 2013;9:5502–5510. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rudnicki M.S., Cirka H.A., Billiar K.L. Nonlinear strain stiffening is not sufficient to explain how far cells can feel on fibrous protein gels. Biophys. J. 2013;105:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.05.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma X., Schickel M.E., Hart R.T. Fibers in the extracellular matrix enable long-range stress transmission between cells. Biophys. J. 2013;104:1410–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stylianopoulos T., Barocas V.H. Volume-averaging theory for the study of the mechanics of collagen networks. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2007;196:2981–2990. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chandran P.L., Barocas V.H. Deterministic material-based averaging theory model of collagen gel micromechanics. J. Biomech. Eng. 2007;129:137–147. doi: 10.1115/1.2472369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fischer R.S., Myers K.A., Waterman C.M. Stiffness-controlled three-dimensional extracellular matrices for high-resolution imaging of cell behavior. Nat. Protoc. 2012;7:2056–2066. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Birmingham E., Niebur G.L., McNamara L.M. Osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells is regulated by osteocyte and osteoblast cells in a simplified bone niche. Eur. Cell. Mater. 2012;23:13–27. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v023a02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haugh M.G., Murphy C.M., O’Brien F.J. Cross-linking and mechanical properties significantly influence cell attachment, proliferation, and migration within collagen glycosaminoglycan scaffolds. Tissue Eng. Part A. 2011;17:1201–1208. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2010.0590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDaniel D.P., Shaw G.A., Plant A.L. The stiffness of collagen fibrils influences vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype. Biophys. J. 2007;92:1759–1769. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.089003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saidi I.S., Jacques S.L., Tittel F.K. Mie and Rayleigh modeling of visible-light scattering in neonatal skin. Appl. Opt. 1995;34:7410–7418. doi: 10.1364/AO.34.007410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Driessen N.J.B., Peters G.W.M., Baaijens F.P.T. Remodelling of continuously distributed collagen fibres in soft connective tissues. J. Biomech. 2003;36:1151–1158. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00082-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mullen C.A., Vaughan T.J., McNamara L.M. Cell morphology and focal adhesion location alters internal cell stress. J. R. Soc. Interface. 2014;11:20140885. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2014.0885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song W., Kawazoe N., Chen G. Dependence of spreading and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells on micropatterned surface area. J. Nanomater. 2011;2011 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kilian K.A., Bugarija B., Mrksich M. Geometric cues for directing the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:4872–4877. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903269107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quarles L.D., Yohay D.A., Wenstrup R.J. Distinct proliferative and differentiated stages of murine MC3T3-E1 cells in culture: an in vitro model of osteoblast development. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1992;7:683–692. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650070613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Golub E., Boesze-Battaglia K. The role of alkaline phosphatase in mineralization. Curr. Opin. Orthop. 2007;18:444–448. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sudo H., Kodama H.A., Kasai S. In vitro differentiation and calcification in a new clonal osteogenic cell line derived from newborn mouse calvaria. J. Cell Biol. 1983;96:191–198. doi: 10.1083/jcb.96.1.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khatiwala C.B., Peyton S.R., Putnam A.J. Intrinsic mechanical properties of the extracellular matrix affect the behavior of pre-osteoblastic MC3T3-E1 cells. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C1640–C1650. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00455.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rowlands A.S., George P.A., Cooper-White J.J. Directing osteogenic and myogenic differentiation of MSCs: interplay of stiffness and adhesive ligand presentation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C1037–C1044. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.67.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang C., Butler P.J., Zhang S. Substrate stiffness regulates cellular uptake of nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 2013;13:1611–1615. doi: 10.1021/nl400033h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lahiri D., Benaduce A.P., Agarwal A. Wear behavior and in vitro cytotoxicity of wear debris generated from hydroxyapatite-carbon nanotube composite coating. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2011;96:1–12. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mante F.K., Baran G.R., Lucas B. Nanoindentation studies of titanium single crystals. Biomaterials. 1999;20:1051–1055. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00257-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haugh M.G., Jaasma M.J., O’Brien F.J. The effect of dehydrothermal treatment on the mechanical and structural properties of collagen-GAG scaffolds. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A. 2009;89:363–369. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bitar M., Salih V., Nazhat S.N. Effect of multiple unconfined compression on cellular dense collagen scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2007;18:237–244. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-0685-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Keogh M.B., O’ Brien F.J., Daly J.S. A novel collagen scaffold supports human osteogenesis—applications for bone tissue engineering. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;340:169–177. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-0939-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim H.W., Knowles J.C., Kim H.E. Hydroxyapatite porous scaffold engineered with biological polymer hybrid coating for antibiotic Vancomycin release. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2005;16:189–195. doi: 10.1007/s10856-005-6679-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]