Abstract

BACKGROUND

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) reduces mortality, improves functional status, and induces reverse left ventricular remodeling in selected populations with heart failure (HF). The magnitude of reverse remodeling predicts survival with many HF medical therapies. However, there are few studies assessing the effect of remodeling on long-term survival with CRT.

OBJECTIVE

The purpose of this study was to assess the effect of CRT-induced reverse remodeling on long-term survival in patients with mildly symptomatic heart failure.

METHODS

The REsynchronization reVErses Remodeling in Systolic Left vEntricular Dysfunction trial was a multicenter, double-blind, randomized trial of CRT in patients with mild HF. Long-term follow-up of 5 years was preplanned. The present analysis was restricted to the 353 patients who were randomized to the CRT ON group with paired echocardiographic studies at baseline and 6 months post-implantation. The left ventricular end-systolic volume index (LVESVi) was measured in the core laboratory and was an independently powered end point of the REsynchronization reVErses Remodeling in Systolic Left vEntricular Dysfunction trial.

RESULTS

A 68% reduction in mortality was observed in patients with ≥15% decrease in LVESVi compared to the rest of the patients (P = .0004). Multivariable analysis showed that the change in LVESVi was a strong independent predictor (P = .0002), with a 14% reduction in mortality for every 10% decrease in LVESVi. Other remodeling parameters such as left ventricular enddiastolic volume index and ejection fraction had a similar association with mortality.

CONCLUSION

The change in left ventricular end-systolic volume after 6 months of CRT is a strong independent predictor of long-term survival in mild HF.

Keywords: Cardiac resynchronization therapy, Heart failure, Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, Defibrillator, Remodeling

Introduction

Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) improves functional status and cardiac function and reduces heart failure (HF) hospitalizations and mortality in patients with HF with left ventricular systolic dysfunction and QRS prolongation.1–8 Initially, CRT was administered to patients with advanced HF, but more recent studies have shown similar benefits in patients with milder HF.9–11 The reverse remodeling response, as measured by left ventricular (LV) volume changes, has important prognostic significance in pharmacological studies of HF, including randomized studies of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors,12,13 angiotensin receptor blockers,14 β-blockers,15,16 and ivabradine.17 There are many other studies supporting the benefits of pharmacological agents used to induce reverse remodeling in HF.18 With regard to CRT, randomized trials showed that reverse remodeling predicts clinical outcomes and arrhythmic events.19,20 However, the long-term effect of remodeling on mortality is less well studied. Accordingly, the present analysis was designed to assess the effect of LV volume changes on all-cause mortality in the preplanned 5-year follow-up period of the REsynchronization reVErses Remodeling in Systolic Left vEntricular Dysfunction (REVERSE) study.

Methods

The design and primary results of the REVERSE trial have been published previously.9,21,22 Briefly, eligible patients had American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association stage C, New York Heart Association class I (previously symptomatic and currently asymptomatic), or New York Heart Association class II (mildly symptomatic). Patients were required to be in sinus rhythm with a QRS duration of ≥120 ms, an LV ejection fraction (EF) of ≤40%, and a left ventricular end-diastolic dimension of ≥55 mm. The ethics committee of each center approved the study protocol, and all patients gave written informed consent.

Patients were enrolled between September 2004 and September 2006. All patients underwent implantation of a CRT system (device and leads), with or without implantable cardioverter-defibrillator capabilities, according to standard clinical criteria.23,24 Patients who had undergone successful implantation (n = 610) were then randomly assigned in a 2:1 fashion to the active CRT (CRT-ON) group or to the control (CRT-OFF) group. The primary end point of the REVERSE trial was the clinical composite score measured at 12 months.21,25 After the randomization period, CRT was programmed ON in all patients for 5 years postimplantation to assess the long-term effect of this therapy.

Echocardiograms were obtained at baseline (before implant) and after 6 months of randomization with CRT turned off temporarily. Data were analyzed in 1 of 2 core laboratories (Philadelphia, PA, and Pavia, Italy) blinded to clinical data. LV dimensions were recorded by 2-dimensional–directed M-mode echocardiography at the tips of the mitral valve leaflets. Echocardiograms were digitized to obtain LV volumes by using Simpson's method of discs, as recommended by the American Society of Echocardiography,26 from which LVEF was calculated. The change in LV end-systolic volume, indexed by body surface area (LVESVi), was the predefined and independently powered secondary end point of the REVERSE trial. Additional echocardiographic measures included left ventricular end-diastolic volume index (LVEDVi) and EF. Further details of the echocardiographic protocol have been published previously.21

Patients were actively followed up with in-office visits at least every 6 months for 5 years of follow-up, at which time patients were exited from the study. Mortality was assessed during the follow-up period, and each death was adjudicated by an independent adverse event adjudication committee to classify the cause of death according to standard criteria.

For the initial analysis of the effect of LVESVi change on mortality, patients were divided into 2 groups by using the commonly used cutoff of a 15% decrease in volume that was prespecified in the REVERSE trial.19,21 Subsequent analyses grouped the changes into quartiles or treated LVESVi change as a continuous variable to allow more detailed assessment of the response.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD and categorical variables as counts and percentages. Time-to-event analyses used Kaplan-Meier estimates and the log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to compute hazard ratios and assess the effect of covariates. Time 0 in these analyses was the date of the 6-month follow-up visit. Subjects were censored using the date of the latest case report form. The covariate analysis of LVESVi (treated as a continuous variable) was performed using the Cox proportional hazards regression model. A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant, and P values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Results

Patient population

Of the 610 patients in the REVERSE trial, 419 were randomized to the CRT-ON group. In this group, 66 subjects were not included in the present analysis for the following reasons: 6 subjects died before their 6-month follow-up, 3 subjects missed their 6-month follow-up, and 57 subjects had inadequate echocardiograms for adequate LVESVi measurements at baseline (n = 23), 6 months (n = 24), or both (n = 8). Thus, 353 patients were included in the present study. Of note, there were no statistically significant differences (P < .05) in baseline characteristics between the included and excluded subjects. The average follow-up duration for the 353 patients was 4.6 years.

The baseline characteristics of the patient population are summarized in Table 1. This was a typical population of patients with mild HF receiving CRT. They were predominantly late middle aged men, with a majority having ischemic heart disease and underlying left bundle branch block (LBBB) on the unpaced electrocardiogram.

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

| LVESVi Change at 6 Months |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased or decreased <15% (n = 170) | Decreased ≥15% (n = 183) | All Patients (n = 353) | p-value | |

| Age, mean (yrs) | 63.8 ± 9.4 | 62.2 ± 11.5 | 63.0 ± 10.6 | 0.15 |

| Male (%) | 148 (87.1) | 122 (66.7) | 270 (76.5) | < 0.0001 |

| Ischemic etiology (%) | 117 (68.8) | 83 (45.4) | 200 (56.7) | < 0.0001 |

| CRT-D (%) | 151 (88.8) | 139 (76.0) | 290 (82.2) | 0.002 |

| NYHA II (%) | 135 (79.4) | 152 (83.1) | 287 (81.3) | 0.41 |

| LBBB | 80 (47.3) | 137 (75.7) | 217 (62.0) | < 0.0001 |

| RBBB | 24 (14.2) | 6 (3.3) | 30 (8.6) | |

| IVCD | 65 (38.5) | 38 (21.0) | 103 (29.4) | |

| LVEF (%) | 26.4 ± 7.3 | 27.2 ± 6.7 | 26.8 ± 7.0 | 0.26 |

| LVESVi (ml/m2) | 97.9 ± 35.7 | 100.8 ± 33.9 | 99.4 ± 34.7 | 0.42 |

| QRS (ms) | 148 ± 20 | 157 ± 21 | 153 ± 20 | < 0.0001 |

| Diabetes (%) | 44 (25.9) | 33 (18.0) | 77 (21.8) | 0.09 |

| ACE Inhibitor or ARB (%) | 163 (95.9) | 177 (96.7) | 340 (96.3) | 0.78 |

| Beta-blocker (%) | 160 (94.1) | 175 (95.6) | 335 (94.9) | 0.63 |

| Diuretics (%) | 137 (80.6) | 144 (78.7) | 281 (79.6) | 0.69 |

Values are presented as n (%). Continuous variables are represented by mean ± standard deviation. Student's t-test or Fisher's exact test are used to test for statistical significance between groups in the first 2 columns.

ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme; ARB = angiotensin receptor blockers;CRT-D = cardiac resynchronization therapy with implantable defibrillator; IVCD = interventricular conduction delay; LBBB = left bundle branch block; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction;LVESVi = left ventricular end-systolic volume index; NYHA = New York Heart Association; RBBB = right bundle-branch block.

Reverse remodeling

The echocardiographic measures of reverse remodeling were assessed after 6 months of CRT. The LVESVi decreased by an average of 14.9 ± 27.5 mL/m2, the LVEDVi decreased by 15.8 ± 32.4 mL/m2, and the EF increased by 3.6% ± 8.3% in this cohort. As shown previously, all these changes were highly significant relative to the unpaced CRT-OFF group.9 The prespecified remodeling end point in this study was a decrease in LVESVi; 183 subjects (52%) had reached the end point of ≥15% decrease in LVESVi. There were some important clinical differences between subjects with a ≥15% decrease in LVESVi and those who did not reach this end point; these results are summarized in Table 1. Those patients with significant remodeling were more likely to be female, have non–ischemic cardiomyopathy, and have typical LBBB. In addition, the unpaced QRS duration was longer.

Survival with CRT

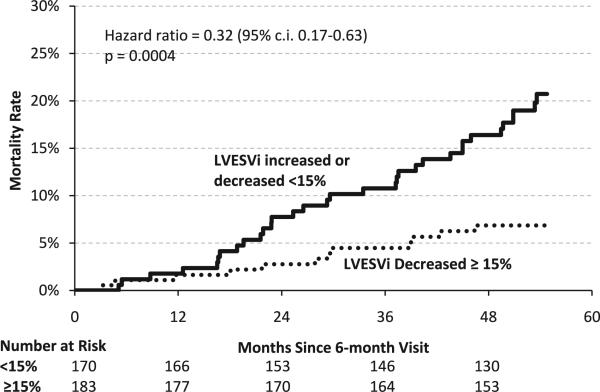

The cohort of the REVERSE trial was followed for 5 years as a preplanned extension phase of the randomized portion of the trial.27 Such long-term follow-up allows for the assessment of mortality, which was low as expected over the first 1–2 years in patients with mild HF.9–11 The mortality curves for the subgroups with and without significant decreases in LVESVi are presented in Figure 1. The curves begin to separate ~15 months after 6-month follow-up, and they continue to separate for the full duration of follow-up. The hazard ratio is 0.32 (P = .0004), indicating a 68% lower mortality rate in subjects who achieved the remodeling end point (≥15% decrease in LVESVi). It is noteworthy that the estimated long-term mortality was low (6.9%) in the subgroup with significant remodeling despite severe systolic dysfunction and QRS prolongation at baseline. Table 2 lists the adjudicated causes of death in the 2 groups. The subgroup achieving the remodeling end point had a lower rate of death in all categories, including sudden and non-sudden cardiac death.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier curves of mortality for the subgroup with ≥15% changes in LVESVI after 6 months of cardiac resynchronization therapy and for the rest of the cohort. CI = confidence interval; LVESVi = left ventricular end-systolic volume index.

Table 2.

Causes of death

| Cause of death | <15% increased or decrease (n = 170) | ≥15% decrease (n = 183) |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiac | ||

| Sudden | 6 (3.5) | 1 (0.5) |

| Nonsudden | ||

| Heart failure | 9 (5.3) | 5 (2.7) |

| Non-heart failure | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) |

| Noncardiac | 16 (9.4) | 5 (2.7) |

| Unknown | 2 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Total | 33 (19.4) | 12 (6.6) |

Values are presented as n (%).

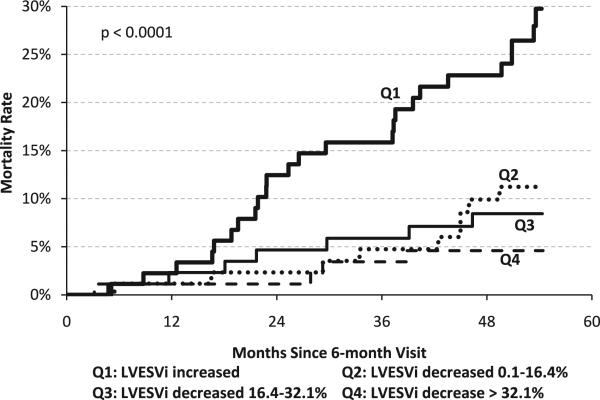

Although a ≥15% decrease in LVESVi is commonly used to define an echocardiographic remodeling response to CRT, this arbitrary cutoff could affect the results. Therefore, the response was subdivided into quartiles to assess the effect on remodeling more accurately. The largest remodeling response (quartile 4) was a >32.1% decrease in LVESVi, whereas patients with an increase in LVESVi despite CRT constituted quartile 1. These results are shown in Figure 2. There was again a significant effect of LVESVi change on mortality (P < .0001), with the lowest mortality being in subjects with the largest decrease and a high mortality in subjects with an increase in LV volume at 6 months.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves of mortality for quartiles based on percentage changes in LVESVi after 6 months of cardiac resynchronization therapy. LVESVi = left ventricular end-systolic volume index.

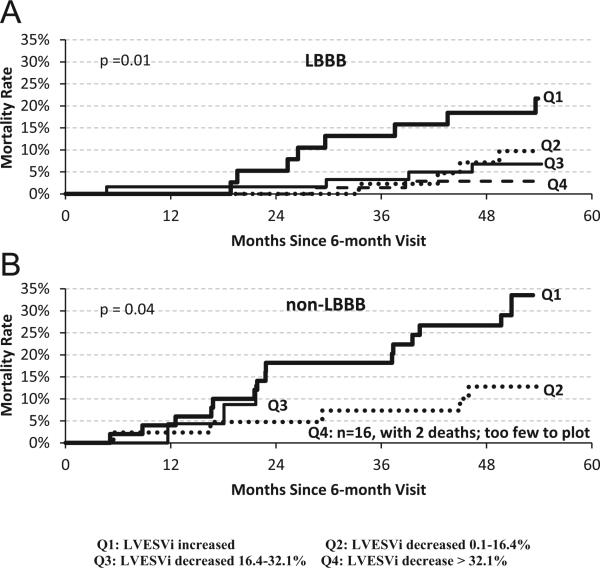

Current guidelines strongly recommend CRT in mild HF only for patients with LBBB28; accordingly, the analysis was repeated in subgroups on the basis of QRS morphology. These results are presented in Figure 3 for the LBBB (n = 217) and non-LBBB (n = 133) cohorts. The P values within both groups were significant, indicating that the change in LVESVi is a significant factor in predicting future mortality in both LBBB and non-LBBB patients.

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier curves of mortality for quartiles based on percentage changes in LVESVi after 6 months of cardiac resynchronization therapy: (A) LBBB; (B) non-LBBB subgroups. LBBB = left bundle branch block; LVESVi = left ventricular end-systolic volume index.

As noted previously, there were some important clinical differences between subjects in the different remodeling subgroups, so a multivariable analysis was performed. For this analysis, the change in LVESVi was treated as a continuous variable. These results are summarized in Table 3. After adjusting for important covariates, remodeling was a strong independent predictor (P = .0002), with a 14% reduction in mortality for every 10% decrease in LVESVi. The other significant predictors of mortality were baseline LVESVi, QRS duration, device type (cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillator [CRT-D] or cardiac resynchronization therapy with pacemaker), and sex, with better survival in subjects with smaller LV volume, subjects with longer QRS duration, CRT-D recipients, and women.

Table 3.

Results of multivariable analysis of mortality after 6 mo of CRT

| Parameter | Comparison | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Change in LVESVi after 6 mo | Per 10% | 0.86 | 0.79-0.93 | .0002 |

| Age | Per 10 y | 1.33 | 0.94-1.87 | .11 |

| Sex | Female vs male | 0.09 | 0.01-0.65 | .02 |

| Ischemic | Ischemic vs non-ischemic | 1.53 | 0.65-3.60 | .33 |

| Baseline LVESVi | Per 10 mL/m2 | 1.16 | 1.07-1.26 | .0003 |

| Baseline QRS duration | Per 10 ms | 0.83 | 0.70-0.99 | .04 |

| LBBB | LBBB vs non-LBBB | 0.56 | 0.28-1.15 | .11 |

| Baseline NYHA | Class I vs class II | 0.71 | 0.32-1.54 | .38 |

| Diabetic | Yes vs no | 0.86 | 0.42-1.76 | .68 |

| Device type | CRT-P vs CRT-D | 2.74 | 1.29-5.81 | .009 |

CI = confidence interval; CRT = cardiac resynchronization therapy;CRT-D = cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillator; CRT-P = cardiac resynchronization therapy with pacemaker; LBBB = left bundle branch block; LVESVi = left ventricular end-systolic volume index; NYHA = New York Heart Association.

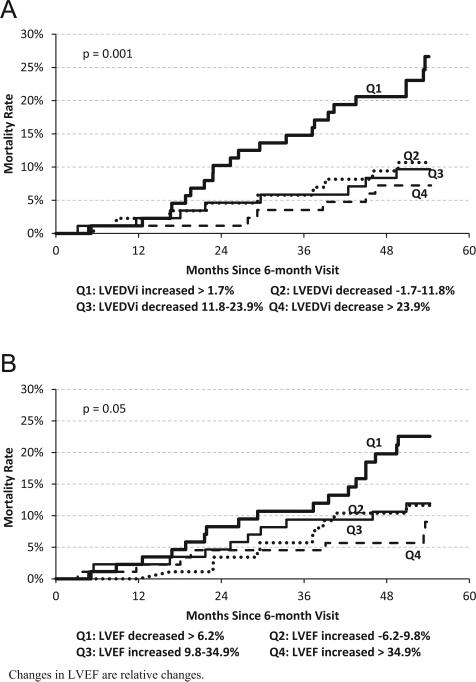

Analyses were also performed with other remodeling parameters. The results for LVEDVi are presented in Figure 4A, and they are strikingly similar to the results for LVESVi. The survival curves grouped by changes in LVEF are shown in Figure 4B. Again, there is a strong association between the magnitude of change in EF and long-term mortality with CRT.

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier curves of mortality for quartiles based on reverse remodeling changes after 6 months of cardiac resynchronization therapy: (A) LVEDVi; (B) LVEF. LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESVi = left ventricular end-systolic volume index.

Discussion

The primary result of the present analysis is that the change in LVESVi with CRT was a strong independent predictor of long-term mortality in mild HF. Specifically, in subjects with a ≥15% decrease in LVESVi after 6 months of CRT, all-cause mortality was 1.6%/y. This was a 68% lower mortality relative to the rest of the cohort. A more detailed analysis of response identified a high-risk cohort with further LV dilation despite CRT, which constituted ~25% of the population. Mortality was >4-fold higher in this subgroup (29.8% vs 6.9% for ≥15% decrease in LVESVi). Finally, the magnitude of other echocardiographic measures of remodeling (LVEDVi and EF) also had a strong association with long-term survival.

The effect of LV volume changes on mortality has been assessed previously in both pharmacological and CRT studies. In the SOLVD treatment trial,29 subjects receiving enalapril had a mean LVESVi decrease of 12.3%. Correspondingly, those patients in the active drug arm had a 16% relative risk reduction in mortality. Other studies of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers have consistently shown the important prognostic effect of echocardiographic volume changes on long-term outcomes and survival.14,18 Studies of carvedilol have also shown an association between reverse remodeling and reduced mortality.15,16 Similar findings were shown with ivabradine therapy in patients already receiving β-blocker therapy.17 Interestingly, an increase in mortality has been observed in the pharmacological treatment that increases LV volumes. This was shown in the trial of ibopamine.30 These findings are supported further by a recent meta-analysis comprising 30 mortality studies, 25 drug/device therapies, and 88 remodeling trials of these therapies in patients with HF. Short-term LV remodeling was associated with lower mortality,18 with more pronounced mortality effects in patients with a greater reduction in LV volumes.

CRT and β-blockers are linked to the greatest magnitude of LV reverse remodeling compared to other HF drug therapies.18 More than 95% of patients in more recent randomized clinical trials of CRT have been receiving β-blockers.10,11 Reverse remodeling by β-blockers depends on dose.15 In the REVERSE trial, 60% were receiving at least 50% of guideline-recommended dose and 30% target dose.31 CRT can be used as in combination with β-blocker therapy, and this combination may be the most potent in terms of reverse remodeling, which is reflected in our results. To our knowledge, the REVERSE trial is the first study to show that reverse remodeling by a nonpharmacological HF therapy is an independent predictor of long-term survival.

Several studies of CRT demonstrated an association between remodeling and composite end points including survival. Ypenburg et al32 reported an association between the extent of LV volume changes and mortality and HF hospitalizations. Similarly, Yu et al33 showed that a 10% decrease in LVESV significantly lowers the risk of mortality and HF events. Finally, the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial–Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy study showed a reduction of the composite end point of HF hospitalization and survival in both the CRT and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator groups.10 The present results suggest that a large decrease in LVESVi is associated with a decrease in both nonsudden and sudden death. The effect of reverse remodeling on HF mortality is not surprising, given the above-mentioned association between remodeling and the reduction of HF hospitalization. LV volume changes have also been shown to decrease ventricular arrhythmia in both the REVERSE19 and Multi-center Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial–Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy34 studies, so again it suggests that a long-term decrease in sudden death may be expected. There was also an apparent decrease in noncardiac death. Whether this was due to the identification of a sicker subgroup of patients more prone to die from the sequela of HF, such as renal failure or infection, or due to mortality classification, difficulties cannot be determined from these results.

The effect of reverse remodeling on long-term mortality was noted for the non-LBBB subgroups. This is particularly interesting, as current guidelines do not recommend CRT for these patients with mild HF due to the results of large randomized trials.10,11 The remodeling response is much smaller in non-LBBB subjects,35–37 which is consistent with poorer outcomes. However, the present results indicate improved survival in those subjects who have a significant decrease in LVESVi with CRT. Further study is needed to assess whether there are predictors of remodeling response in the non-LBBB cohort who may benefit from CRT.

There are several clinical implications of these data. First, the present findings confirm that echocardiographic measures of remodeling are an important end point for CRT response. Such responses at 6 months are a strong predictor of mortality, so this should be considered as an end point for studies designed to optimize CRT, as it would save considerable sample size and time over studies using mortality as an end point. Second is the observation that further LV dilation despite CRT is a poor prognostic sign with a high mortality. These patients should be considered for intervention including alternative advanced HF therapy optimization of programming parameters, lead repositioning, or even discontinuation of CRT. Finally, the clinical predictors of long-term mortality with CRT are similar to the predictors of clinical response in mild HF.9–11,34–36 Specifically, in addition to the change in LVESVi, female sex, increased unpaced QRS duration, CRT-D devices, and smaller LV volumes were associated with lower mortality. CRT-D had been previously shown to be associated with reduced mortality,38 while other factors were shown to be associated with reduced HF hospitalizations.9–11

This study should be interpreted in the face of several methodological limitations. The REVERSE study was double-blinded only during the randomized phase, including the echocardiographic assessment. It is conceivable that this affected treatment at different phases of the study. In addition, titration of medications was discouraged during the randomized phase and this may affect long-term outcomes. Finally, this study evaluated only subjects with mild HF.

Conclusion

In the long-term follow-up of REVERSE patients with CRT, reverse remodeling, defined as a ≥15% decrease in LVESVi, was associated with a 68% reduction in mortality. Analysis adjusting for baseline covariates showed a 14% reduction in mortality for every 10% decrease in LVESVi. Finally, the subgroup of patients who continue to remodel despite CRT (LVESVi increases) has a markedly increased mortality.

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVES.

Pharmacologic therapies for systolic heart failure that are associated with reverse left ventricular remodeling produce a mortality benefit. The present study assessed the long-term effect of reverse remodeling on mortality with cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT). A ≥15% decrease in left ventricular end-systolic volume index, which is the standard measure of remodeling with CRT, was associated with a 68% reduction in all-cause mortality. Similar results were observed with other remodeling parameters, including a decrease in left ventricular end-diastolic volume index or an increase in ejection fraction. Equally important, the subgroup of patients who continue to remodel despite CRT have a markedly increased mortality. These findings indicate that reverse remodeling should be a goal of CRT and is an appropriate short-term (6-month) end point for interventions aiming to optimize this treatment. Such interventions include physiological measures to optimize left ventricular lead position or programmed pacing parameters. However, continued left ventricular dilation with CRT is a marker of a poor prognosis and warrants aggressive treatment, such as alternative heart failure therapies or inhibiting CRT.

Acknowledgments

The REVERSE trial was supported by Medtronic. Dr Gold served as consultants to and received research grants from Medtronic and St Jude Medical; he also received consulting fees from Biotronik, Sorin, and Boston Scientific. Dr Linde served as consultants to and received research grants from Medtronic and St Jude Medical; she also received honoraria from Biotronik and St Jude Medical. Dr Daubert served as consultants to and received research grants from Medtronic. Dr Abraham received consulting fees from Biotronik, Medtronic, and St Jude Medical. Mr Hudnall and Mr Cerkvenik are employees of Medtronic.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CRT

cardiac resynchronization therapy

- CRT-D

cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillator

- EF

ejection fraction

- HF

heart failure

- LBBB

left bundle branch block

- LV

left ventricular

- LVEDVi

left volume ventricular end-diastolic index

- LVESVi

left ventricular end-systolic volume index

- REVERSE

REsynchronization reVErses Remodeling in Systolic Left vEntricular Dysfunction

References

- 1.Cazeau S, Leclercq C, Lavergne T, Walker S, Varma C, Linde C, Garrigue S, Kappenberger L, Haywood GA, Santini M, Bailleul C, Daubert JC. Multisite Stimulation in Cardiomyopathies (MUSTIC) Study Investigators. Effects of multisite biventricular pacing in patients with heart failure and intraventricular conduction delay. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:873–880. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103223441202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abraham WT, Fisher WG, Smith AL, et al. MIRACLE Study Group. Multicenter InSync Randomized Clinical Evaluation. Cardiac resynchronization in chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1845–1853. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linde C, Leclercq C, Rex S, et al. Long-term benefits of biventricular pacing in congestive heart failure: results from the MUltisite STimulation in cardiomyopathy (MUSTIC) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:111–118. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01932-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins SL, Hummel JD, Niazi IK, Giudici MC, Worley SJ, Saxon LA, Boehmer JP, Higginbotham MB, De Marco T, Foster E, Yong PG. Cardiac resynchronization therapy for the treatment of heart failure in patients with intraventricular conduction delay and malignant ventricular tachyarrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1454–1459. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)01042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young JB, Abraham WT, Smith AL, Leon AR, Lieberman R, Wilkoff B, Canby RC, Schroeder JS, Liem LB, Hall S, Wheelan K. Multicenter InSync ICD Randomized Clinical Evaluation (MIRACLE ICD) Trial Investigators. Combined cardiac resynchronization and implantable cardioversion defibrillation in advanced chronic heart failure: the MIRACLE ICD Trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2685–2694. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.20.2685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bristow MR, Saxon LA, Boehmer J, Krueger S, Kass DA, De Marco T, Carson P, DiCarlo L, DeMets D, White BG, DeVries DW, Feldman AM. Comparison of Medical Therapy, Pacing, and Defibrillation in Heart Failure (COMPANION) Investigators. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2140–2150. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cleland JG, Daubert JC, Erdmann E, Freemantle N, Gras D, Kappenberger L, Tavazzi L. Cardiac Resynchronization-Heart Failure (CARE-HF) Study Investigators. The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1539–1549. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cleland JG, Daubert JC, Erdmann E, Freemantle N, Gras D, Kappenberger L, Tavazzi L. Longer-term effects of cardiac resynchronization therapy on mortality in heart failure [the CArdiac REsynchronization-Heart Failure (CARE-HF) trial extension phase]. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1928–1932. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linde C, Abraham WT, Gold MR, St John Sutton M, Ghio S, Daubert C. REVERSE (REsynchronization reVErses Remodeling in Systolic left vEntricular dysfunction) Study Group. Randomized trial of cardiac resynchronization in mildly symptomatic heart failure patients with left ventricular dysfunction and previous heart failure symptoms. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1834–1843. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for the prevention of heart-failure events. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1329–1338. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0906431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang AS, Wells GA, Talajic M, et al. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for mild-to-moderate heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2385–2395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Konstam MA, Kronenberg MW, Rousseau MF, Udelson JE, Melin J, Stewart D, Dolan N, Edens TR, Ahn S, Kinen D. Effects of the angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, enalapril, on the long-term progression of left ventricular dilatation in patients with asymptomatic systolic dysfunction. Circulation. 1993;88:2277–2283. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.5.2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Konstam MA, Patten RD, Thomas I, et al. Effects of losartan and captopril on left ventricular volumes in elderly patients with heart failure: results of the ELITE ventricular function substudy. Am Heart J. 2000;139:1081–1087. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.105302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pitt B, Poole-Wilson PA, Segal R, Martinez FA, Dickstein K, Camm AJ, Konstam MA, Riegger G, Klinger GH, Neaton J, Sharma D, Thiyagarajan B. Randomised trial of losartan versus captopril on mortality in patients with symptomatic heart failure: the Losartan Heart Failure Survival Study ELITE II. Lancet. 2000;355:1582–1587. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bristow MR, Gilbert EM, Abraham WT, Adams KF, Fowler MB, Hershberger RE, Kubo SH, Narahara KA, Ingersoll H, Krueger S, Young S, Shusterman N. MOCHA Investigators. Carvedilol produces dose related improvements in left ventricular function and survival in subjects with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 1996;94:2807–2816. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.11.2807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Colucci WS, Kolias TJ, Adams KF, Armstrong WF, Ghali JK, Gottlieb SS, Greenberg B, Klibaner MI, Kukin ML, Sugg JE, REVERT Study Group Metoprolol reverses left ventricular remodeling in patients with asymptomatic systolic dysfunction: the REversal of VEntricular Remodeling with Toprol-XL (REVERT) trial. Circulation. 2007;116:49–56. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.666016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tardif JC, O'Meara EO, Komajda M, Böhm M, Borer JS, Ford I, Tavazzi L, Swedberg K, SHIFT Investigators Effects of selective heart rate reduction with ivabradine on left ventricular remodeling and function: results from the SHIFT echocardiography substudy. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2507–2515. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kramer DG, Trikalinos TA, Kent DM, Antonopoulos GV, Konstam MA, Udelson JE. Quantitative evaluation of drug and device effects on ventricular remodeling as predictors of therapeutic effects on mortality in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:392–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gold MR, Linde C, Abraham WT, Gardiwal A, Daubert JC. The impact of cardiac resynchronization therapy on the incidence of ventricular arrhythmias in mild heart failure. Heart Rhythm. 2011;8:679–684. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2010.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barsheshet A, Wang PJ, Moss AJ, Solomon SD, Al-Ahmad A, McNitt S, Foster E, Huang DT, Klein HU, Zareba W, Eldar M, Goldenberg I. Reverse remodeling and the risk of ventricular tachyarrhythmias in the MADIT-CRT (Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial-Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:2416–2423. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linde C, Gold M, Abraham WT, Daubert JC, for the REVERSE Study Group Rationale and design of a randomized controlled trial to assess the safety and efficacy of cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction with previous symptoms or mild heart failure—the REsynchronization reVErses Remodeling in Systolic left vEntricular dysfunction (REVERSE) study. Am Heart J. 2006;151:288–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daubert JC, Gold MR, Abraham WT, Ghio S, Hassager C, Goode G, Szili-Török T, Linde C, REVERSE Study Group Prevention of disease progression by cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic left ventricular dysfunction: insights from the European cohort of the REsynchronization reVErses Remodeling in Systolic left vEntricular dys-function (REVERSE) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1837–1846. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gregoratos G, Abrams J, Epstein AE, Freedman RA, Hayes DL, Hlatky MA, Kerber RE, Naccarelli GV, Schoenfeld MH, Silka MJ, Winters SL. ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 guideline update for implantation of cardiac pacemakers and antiarrhythmia devices: summary article. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/NASPE Committee to Update the 1998 Pacemaker Guidelines). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1703–1719. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02528-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Priori SG, Aliot E, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, et al. Update of the guidelines on sudden cardiac death of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:13–15. doi: 10.1016/s0195-0668x(02)00809-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Packer M. Proposal for a new clinical end point to evaluate the efficacy of drugs and devices in the treatment of chronic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2001;7:176–182. doi: 10.1054/jcaf.2001.25652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Linde C, Gold MR, Abraham WT, St John Sutton M, Ghio S, Cerkvenik J, Daubert C, REsynchronization reVErses Remodeling in Systolic left vEntricular dysfunction Study Group Long-term impact of cardiac resynchronization therapy in mild heart failure: five year results from the REsynchronization reverses Remodeling in Systolic left vEntricular dysfunction (REVERSE) study. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2592–2599. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Epstein AE, DiMarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused update incorporated into the ACCF/AHA/HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:e6–e75. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The SOLVD Investigators Effect of enalapril on survival in patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fractions and congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:293–302. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108013250501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rousseau MF, Konstam MA, Benedict CR, Donckier J, Galanti L, Melin J, Kinan D, Ahn S, Ketelslegers JM, Pouleur H. Progression of left ventricular dysfunction secondary to coronary artery disease, sustained neurohormonal activation and effects of ibopamine therapy during long-term therapy with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Am J Cardiol. 1994;73:488–493. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90680-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linde CM, Gold M, Abraham WT, Daubert JC, on behalf of the REVERSE Study Group Baseline characteristics of patients randomised in REsynchronization reverses Remodeling in Systolic left vEntricular dysfunction (REVERSE) study. Congest Heart Fail. 2008;14:66–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2008.07613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ypenburg C, van Bommel RJ, Borleffs CJ, Bleeker GB, Boersma E, Schalij MJ, Bax JJ. Long-term prognosis after cardiac resynchronization therapy is related to the extent of left ventricular reverse remodeling at midterm follow-up. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:483–490. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu CM, Bleeker GB, Fung JW, Schalij MJ, Zhang Q, van der Wall EE, Chan YS, Kong SL, Bax JJ. Left ventricular reverse remodeling but not clinical improvement predicts long-term survival after cardiac resynchronization therapy. Circulation. 2005;112:1580–1586. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.538272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Solomon SD, Foster E, Bourgoun M, Shah A, Viloria E, Brown MW, Hall WJ, Pfeffer MA, Moss AJ. MADIT-CRT Investigators. Effect of cardiac resynchronization therapy on reverse remodeling and relation to outcome: Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial: Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy. Circulation. 2010;122:985–992. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.955039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sutton MSJ, Ghio S, Plappert T, Tavazzi L, Scelsi L, Daubert C, Abraham WT, Gold MR, Hassager C, Herre JM, Linde C. REsynchronization reVErses Remodeling in Systolic left vEntricular dysfunction (REVERSE) Study Group. Cardiac resynchronization induces major structural and functional reverse remodeling in patients with New York Heart Association class I/II heart failure. Circulation. 2009;120:1858–1865. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.818724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldenberg I, Moss AJ, Hall W, et al. Predictors of response to cardiac resynchronization therapy in the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial With Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy (MADIT-CRT). Circulation. 2011;124:1527–1536. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.014324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gold MR, Thebault C, Linde C, Abraham WT, Gerritse B, Ghio S, St John Sutton M, Daubert JC. Effect of QRS duration and morphology on cardiac resynchronization therapy outcomes in mild heart failure: results from the Resynchronization Reverses Remodeling in Systolic Left Ventricular Dysfunction (REVERSE) study. Circulation. 2012;126:822–829. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.097709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gold MR, Daubert JC, Abraham WT, Hassager C, Dinerman JL, Hudnall JH, Cerkvenik J, Linde C. Implantable defibrillators improve survival in patients with mildly symptomatic heart failure receiving cardiac resynchronization therapy: analysis of the long-term follow-up of Remodeling in Systolic Left Ventricular Dysfunction (REVERSE). Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2013;6:1163–1168. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.113.000570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]