Abstract

Central sleep apnea (CSA) is a highly prevalent, though often unrecognized, comorbidity in patients with heart failure (HF). Data from HF population studies suggest that it may present in 30% to 50% of HF patients. CSA is recognized as an important contributor to the progression of HF and to HF-related morbidity and mortality. Over the past 2 decades, an expanding body of research has begun to shed light on the pathophysiologic mechanisms of CSA. Armed with this growing knowledge base, the sleep, respiratory, and cardiovascular research communities have been working to identify ways to treat CSA in HF with the ultimate goal of improving patient quality of life and clinical outcomes. In this paper, we examine the current state of knowledge about the mechanisms of CSA in HF and review emerging therapies for this disorder.

Keywords: apnea-hypopnea index, continuous positive airway pressure, hypoxia, reactive oxygen species, reoxygenation

Congestive heart failure (HF) remains a major public health problem and continues to be associated with substantial morbidity and mortality. One factor now recognized as contributing to the excess morbidity and mortality in HF is sleep-disordered breathing. This condition is characterized by cycles of significant pauses in breathing and partial neurological arousals that ultimately have an impact on sleep quality and overall health. Sleep-disordered breathing is broadly classified into 2 types: obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and central sleep apnea (CSA). The former is common and occurs in both the general and HF populations, whereas the latter is more uniquely associated with HF (1–3).

In OSA, repeated episodes of partial or complete upper airway obstruction occur during sleep. This obstruction causes loud snoring, repeated episodes of apnea and hypoxia, and arousals from sleep. These episodes of obstruction, hypoxia, and arousal lead to the development and progression of a number of cardiovascular disorders, including systemic hyper-tension, cardiac arrhythmias, myocardial ischemia and infarction, and HF (4,5). Because of its high prevalence in both the general and HF populations, OSA has been well studied, and effective methods to treat it have been developed (4,6). Of these therapies, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the primary therapeutic option, with several studies demonstrating that it significantly improves symptoms, such as snoring, morning headaches, and daytime sleepiness (7–9). CPAP has also been shown to significantly reduce blood pressure, and several studies suggest that it may reduce OSA-related mortality (10–12).

Most often seen in HF patients, CSA is distinguished by the temporary withdrawal of central (brainstem-driven) respiratory drive that results in the cessation of respiratory muscle activity and airflow. In HF patients, CSA commonly occurs in the form of Cheyne-Stokes respiration, a form of periodic breathing with recurring cycles of crescendodecrescendo ventilation that culminates in a prolonged apnea or hypopnea. Like OSA, the presence of CSA in patients with HF is associated with a set of neurohumoral and hemodynamic responses that are detrimental to the failing heart (13–16). However, unlike OSA, the underlying pathophysiology of CSA and its consequences in HF have only more recently been recognized and understood. With this expanding knowledge base, clinicians have been working to identify ways to treat CSA in HF with the ultimate goal of improving patient quality of life (QOL) and clinical outcomes. Thus, in this paper, we will focus on the current state of knowledge about the mechanisms of CSA in HF and review emerging therapies for this disorder.

CSA: PRESENTATION AND RISK FACTORS

Highly prevalent in HF, CSA occurs in 30% to 50% of patients (1–3). Clinically, HF patients with CSA may experience insomnia, fatigue, and/or daytime sleepiness, although the latter is often absent (17–19). Sometimes, a sleep partner may report witnessed apneas or the unusual breathing pattern of Cheyne-Stokes respiration. Patients may also report frequent awakenings, poor quality sleep, shortness of breath, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, and nocturia (1). However, because these common findings can be due to HF itself, the presence of CSA is often overlooked by patients and clinicians, and failure to treat CSA potentially leads to a prognosis worse than that attributable to HF alone.

A number of risk factors have been identified for the development of CSA in HF, including male sex, higher New York Heart Association functional class, lower ejection fraction, waking hypocapnia (arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide [PaCO2] <38 mm Hg), higher prevalence of atrial fibrillation, higher B-type natriuretic peptide levels, and frequent nocturnal ventricular arrhythmias (3,18–20). No questionnaire-based screening tool has been validated to identify CSA in HF; therefore, a high index of suspicion for CSA should exist when 1 or more of these findings are present in a patient with HF (21).

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

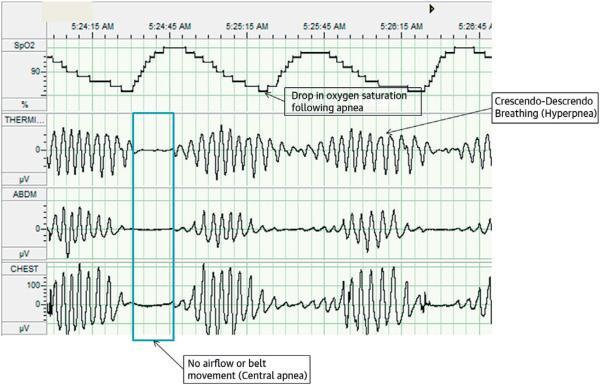

The gold standard test for diagnosing CSA is polysomnography, or overnight sleep study, which is performed in a sleep laboratory. Characteristic polysomnographic findings of CSA include: an onset near the transition into or out of stage 1, nonrapid eye movement sleep; cycles of deep, rapid, crescendodecrescendo breathing followed by periods of hypopnea and/or apnea along with concomitant changes in blood oxygen saturation; and apneic periods accompanied by the absence of chest or abdominal wall activity (Figure 1) (22). A common measure of the severity of CSA is the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), defined as the mean number of apnea and/or hypopnea episodes that occur during sleep divided by the number of hours of sleep, and is expressed in events per hour. According to 1 study, receiver-operating characteristic analysis of different AHI levels revealed that an AHI of 22.5 events/h had the greatest sensitivity and specificity in predicting mortality associated with CSA (23). Another study of ambulatory HF patients showed that mortality rose progressively with every 5 events/h increase in AHI (24). Because the detrimental effects of CSA increase with the increasing number of CSA events, reducing AHI should be the main focus of treatment.

FIGURE 1. Polysomnogram of CSA in a Patient With Heart Failure.

Overnight polysomnography performed in a sleep laboratory remains the gold standard for diagnosing sleep-disordered breathing. The image highlights characteristic findings of central sleep apnea (CSA) on a polysomnogram.

PATHOGENESIS OF CSA IN HF

The pathogenesis of CSA in HF is complex and remains incompletely understood. However, a substantial body of research suggests that an increased respiratory control response to changes in PaCO2 above and below the apneic threshold is central to the pathogenesis of CSA in HF (25–27). An understanding of normal respiratory control in both the awake and sleeping states can aid in understanding the current theories regarding CSA pathogenesis.

The respiratory control system consists of a complex matrix of peripheral and central receptors and rhythm generators interacting continuously with the lung, chest wall, and arterial blood gas content (28–31). This system operates in a negative feedback loop while performing its task of maintaining tightly regulated levels of O2 and CO2 under the numerous demands from human activity, disease, and aging. During wakefulness, normal breathing is influenced by both metabolic and behavioral factors. Metabolic factors (such as exercise-induced acidosis or diuretic-related alkalosis) alter the rate of production of CO2 and modify breathing in response to input from central and peripheral chemoreceptors. On the basis of input from these receptors, tidal volume and breathing rate are modified to maintain CO2 within a tight range. Behavioral factors also alter breathing through involuntary (e.g., stress) and voluntary (e.g., talking or breath holding) respiratory acts.

During sleep, behavioral factors are largely eliminated, leaving the control of breathing entirely to metabolic factors. Therefore, PaCO2 becomes the only stimulus for ventilation during sleep. As such, any increase in PaCO2 will stimulate ventilation, whereas any decrease in PaCO2 will suppress it. Respiration will cease altogether if PaCO2 falls below the tightly regulated level called the apneic threshold. Normally, at the onset of sleep, ventilation decreases and PaCO2 increases. This keeps the prevailing level of PaCO2 well above the apneic threshold, allowing normal, rhythmic breathing to continue throughout the night.

In patients with HF, significant alterations of sleep occur at night due to changes associated with their disease. Three main factors are currently theorized to interact and lead to respiratory instability in HF: hyperventilation, circulatory delay, and cerebrovascular reactivity. Alterations in these 3 factors destabilize normal breathing, leading to respiratory instability and the rhythmic pattern of breathing referred to as Cheyne-Stokes respiration.

HF patients have a tendency to chronically hyper-ventilate; why this occurs is not completely understood, although several mechanisms are believed to be involved (25,26,32). Pulmonary interstitial congestion due to rostral fluid displacement from the legs to the chest and lungs while in the supine position during sleep activates pulmonary stretch receptors that stimulate ventilation (33–36). Additionally, the underlying cardiac disease activates peripheral chemoreceptors, which triggers an exaggerated response by the body to the lowered level of CO2, resulting in an apnea. This apnea produces a significant increase in CO2, resulting in another exaggerated response–hyperventilation–setting up the cyclical pattern of Cheyne-Stokes respiration (37,38). Upper airway instability also plays a unique role in CSA. With sleep onset, upper airway resistance increases due to the normal sleep-related decrease of muscular tone. It has been proposed that upper airway obstruction may promote ventilatory overshoot following the sudden reduction in upper airway resistance that occurs at the termination of apnea (39–41). Although any or all of these factors can lead to the hyperventilation noted in HF patients with CSA, the resulting increased ventilatory rate prevents the expected rise in PaCO2, leading to apnea.

Due to the decreased cardiac output in HF patients, circulation time increases, which delays detection of changes in blood gases between the peripheral and the central chemoreceptors. This prolongs information feedback from the peripheral chemoreceptors to the brain, which ultimately alters respiration. Studies in HF patients with CSA have shown that lung-to-ear circulation time, a surrogate measure of circulatory delay, correlates inversely with cardiac output, and that circulatory delay influences the cycle duration of the waxing-waning pattern of periodic breathing seen with CSA (42). This was initially believed to be the primary mechanism of CSA development, but now is thought to be just 1 of several factors that destabilize breathing leading to the cyclical breathing pattern seen in CSA.

Respiratory-induced changes in the PaCO2 play a key role in regulating cerebral blood flow. Alterations in cerebral blood flow caused by changes in PaCO2 are referred to as cerebrovascular reactivity. Studies of patients with HF and CSA have shown that they have a diminished cerebrovascular response to CO2 and this may be another important contributor to the breathing instabilities seen in these patients during sleep (43). Because HF patients with CSA have reduced cerebrovascular reactivity to CO2, the normal buffering action to changes in central hydrogen ion concentration ([H+]) is impaired, resulting in a greater increase in the PaCO2 and [H+] at the central chemoreceptor during hypercapnia and a greater reduction in PaCO2 and [H+] during hypocapnia for a given change in PaCO2 (43). This reduces the ability of the central respiratory control center to adequately dampen ventilatory undershoots or overshoots, such as those seen during apnea or at apnea termination. In this way, impaired cerebrovascular reactivity also may contribute to breathing instabilities during sleep and predispose a patient to the onset and perpetuation of CSA (43).

Although numerous factors contribute to CSA development, once begun, the cyclical pattern continues to perpetuate the instability. Each episode results in hypoxia and a relative increase in CO2, which increases the likelihood of the cycle repeating. Stabilization of gas exchange and/or improvement in receptor activation is needed to break the abnormal pattern of breathing.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGIC CONSEQUENCES

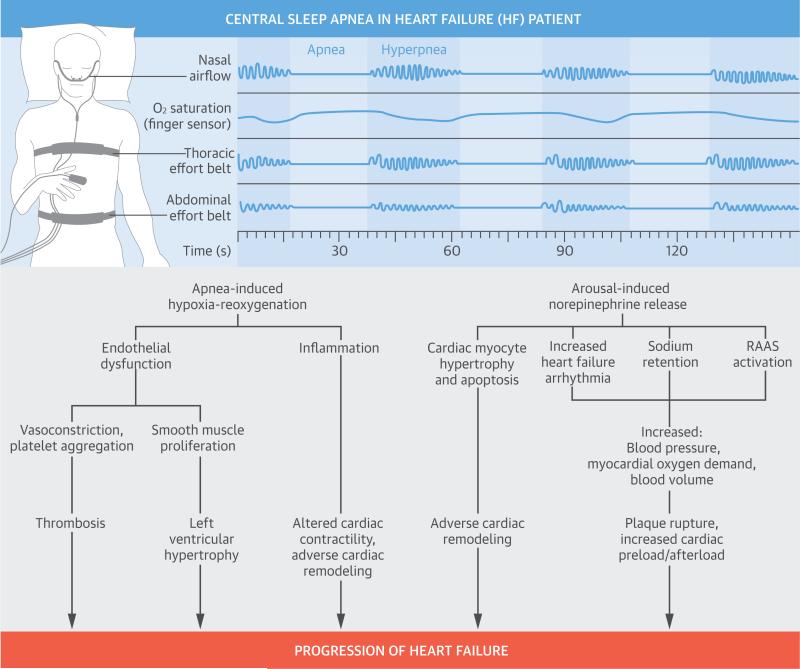

Oscillation of the PaCO2 around the apneic threshold appears to be the key factor in CSA development and perpetuation in patients with HF. The resulting repeated episodes of apnea, hypoxia, reoxygenation, and arousal throughout the night are the factors leading to the pathophysiologic consequences of CSA. There are multiple pathologic effects including sympathetic nervous system activation, oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction (Central Illustration). Data regarding the pathophysio-logical consequences of apnea-induced hypoxiareoxygenation comes largely from studies of patients with OSA. Thus, findings regarding the metabolic and cardiovascular effects of OSA are extrapolated to CSA in the absence of direct evaluation in the CSA population. Data obtained from patients with HF were used when available and are described in the following text.

CENTRAL ILLUSTRATION. Pathophysiologic Consequences of CSA in Heart Failure.

The repeated episodes of apnea, hypoxia, reoxygenation, and arousal throughout the night are the factors leading to the pathophysiologic consequences of central sleep apnea (CSA). These pathologic effects are multiple, and include sympathetic nervous system activation, oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction. All contribute to worsening heart failure. RAAS = renin-angiotensin aldosterone system.

SYMPATHETIC NERVOUS SYSTEM ACTIVATION

A key pathological consequence of CSA in HF is increased sympathetic nervous system activity during sleep. Patients with sleep apnea exhibit repeated bursts of sympathetic activity with each respiratory event cycle and subsequent arousal (14,44). In severe cases of CSA, these surges in sympathetic activity may occur many times during the night and, importantly, arise in addition to the chronic up-regulation in sympathetic activity already present in HF (45). This holds high clinical relevance because increased sympathetic nervous system activity is associated with increased mortality in HF patients (46–48). Evidence for further sympathoexcitation during central apneic events comes from studies demonstrating that overnight urinary excretion of norepinephrine and early morning plasma concentrations of norepinephrine are both elevated in CSA patients (14,49).

The adverse effects of catecholamines in the setting of HF are well recognized (50). Sustained sympathetic stimulation causes tachycardia, peripheral vasoconstriction, sodium retention, and reninangiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) activation. The resulting increases in myocardial oxygen demand, blood pressure, and blood volume lead to increased myocardial ischemia, pre-load, and after-load that together further stress the failing heart. Furthermore, excessive sympathetic activity is associated with cardiac myocyte hypertrophy and apoptosis and focal myocardial necrosis, all of which contribute to cardiac remodeling. Heightened sympathetic activity also precipitates cardiac arrhythmias in the setting of left ventricular (LV) dysfunction, and the additional sympathoexcitation induced by CSA may further enhance arrhythmogenesis (51). Indeed, several studies have found that HF patients with CSA experience increased ventricular irritability including an increased risk for malignant ventricular arrhythmias (15,51–53) and a frequent association between atrial fibrillation and CSA (1).

OXIDATIVE STRESS

Oxidative stress is increasingly recognized as an important pathological mechanism in the development and progression of HF (54,55). On the basis of findings from a number of experimental and clinical studies, recurrent episodes of intermittent hypoxia-reoxygenation, such as those that occur with sleep apneas, appear to increase systemic oxidative stress (56).

Oxidative stress occurs when there is an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and endogenous antioxidant defenses. ROS, which are produced via the electron reduction of molecular oxygen (O2), include superoxide anion radical (•O2−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and the hydroxyl radical (•OH). Excess ROS cause tissue damage through oxidative modification of essential cellular biological molecules, such as lipids, proteins, and deoxyribonucleic acid. ROS are believed to contribute to HF progression through a number of different mechanisms, including impairment of myocardial contractility, involvement in molecular signaling processes that lead to cardiac remodeling, and interference with nitric oxide metabolism, which is critically important to normal endothelial function (54,55).

With sleep apnea, it has been proposed that excess ROS are generated by myocytes and other tissues throughout the body as they attempt to cope with alternating extremes in oxygen levels experienced during repeated episodes of hypoxia-reoxygenation (56). Apnea-induced hypoxia-reoxygenation has been likened to the events occurring with ischemiareperfusion injury seen in the settings of myocardial infarction, stroke, and other ischemic processes (57–60). It is postulated that during ischemiareperfusion, lack of oxygen leads to the accumulation of metabolic intermediates. With reperfusion, these reactions proceed with a sudden increase in ROS, which overwhelms usual cellular antioxidant defenses, leading to uncontrolled oxidation of vital cellular biomolecules (56). Experimental data support this hypothesis, and an expanding body of research suggests that it may apply to patients with sleep apnea as well (56,61–63).

Clinically, changes in endogenous oxidative stress are detected by measuring various biomarkers (i.e., oxidized products of biological molecules that result from the production of ROS) in the blood. Widely used biomarkers of oxidative stress include lipid peroxidation products and oxidized protein and deoxyribonucleic acid (60). In controlled clinical studies of OSA patients, levels of these biomarkers have been shown to be elevated, suggesting increased levels of systemic oxidative stress (60,64–68). Similarly, other studies have evaluated the antioxidant capacity in patients with OSA by measuring small molecule antioxidant levels in the blood. Antioxidant capacity would be expected to fall in the presence of increased oxidative stress; thus, its measurement offers another method of measuring oxidative stress. Indeed, research has demonstrated decreased anti-oxidant levels in sleep apnea (60,69,70). Importantly, oxidative stress has been shown to improve with the application of CPAP therapy (63,71,72). This finding provides important evidence of the potential role that sleep apnea may have in increasing oxidative stress.

INFLAMMATION

Inflammation is recognized as playing a key role in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease (CVD), including HF (73–77). In HF, elevated levels of pro-inflammatory mediators are known to have an adverse impact on LV function through their effects on cardiac contractility, metabolism, and remodeling (78). Inflammation also has been shown to contribute to pulmonary edema as well as to the anorexia and cachexia frequently occurring in patients with advanced HF (75,78). Elevated levels of pro-inflammatory mediators independently predict increased mortality in HF patients (79,80). Similar to oxidative stress, the study of inflammation in sleep apnea has been explored primarily in OSA patients.

Several studies have demonstrated that patients with sleep apnea have enhanced levels of plasma markers of systemic inflammation. In particular, increased amounts of pro-inflammatory cytokines, cellular adhesion molecules, and activated circulating neutrophils have been detected in sleep apnea patients (81–83). These findings suggest that sleep apnea, by contributing to the heightened inflammatory state seen in HF patients with sleep apnea, may promote further HF progression.

Mechanistically, it has been proposed that the increased levels of ROS resulting from apnea-induced hypoxia-reoxygenation may trigger the expression of multiple pro-inflammatory genes via activation of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) (84–85). NF-κB is recognized as 1 of the most important oxidation-sensitive transcription factors, and it plays a key role in activating numerous genes, including many of those associated with CVD (86). Studies measuring NF-κB activity in circulating neutrophils and monocytes in both sleep apnea and control patients have detected increased NF-κB activity in patients with OSA (87,88). Importantly, NF-κB activity is reduced by the application of CPAP therapy, demonstrating a potential causal link between NF-κB activation and the pathophysiology of sleep apnea (87,88).

ENDOTHELIAL DYSFUNCTION

Both oxidative stress and inflammation are major components in the initiation and development of endothelial dysfunction, a critical component of the pathophysiology of many CVDs including HF (89–91). Endothelial dysfunction in HF is characterized by a shift of the actions of the endothelium toward vasoconstriction, inflammation, and thrombosis, which together contribute to the development of impaired coronary and systemic perfusion seen in patients with HF (92,93).

Normal endothelial function critically depends on the presence of nitric oxide. Two major contributors to endothelial dysfunction include reduced bioavailability of nitric oxide and excess formation of ROS within the vascular wall (92,94). Reactive oxygen species are known to reduce bioavailable nitric oxide and exacerbate local oxidant stress by reacting directly with nitric oxide to form the potent oxidant, peroxynitrite (92–95). Apnea-induced intermittent hypoxia-reoxygenation, through its ability to increase ROS, may, therefore, contribute to increased endothelial dysfunction. Research has detected the presence of endothelial dysfunction in patients with OSA (96). CPAP therapy may reverse this abnormality, supporting a potential link between sleep apnea and endothelial dysfunction (96).

TREATMENT

Optimization of HF therapy is of paramount importance, as a number of studies have shown that once HF is clinically improved, CSA may improve as well (97–99). Optimal HF therapy includes diuresis to reduce pulmonary congestion, beta-blockers to blunt the effects of sympathetic nervous system activation, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors to reduce ventricular afterload and improve cardiac output by blockading the effects of the RAAS (100). Additionally, small studies have shown that inotropic therapy and cardiac transplantation also may reduce the severity of or resolve CSA in patients with chronic HF (101–103).

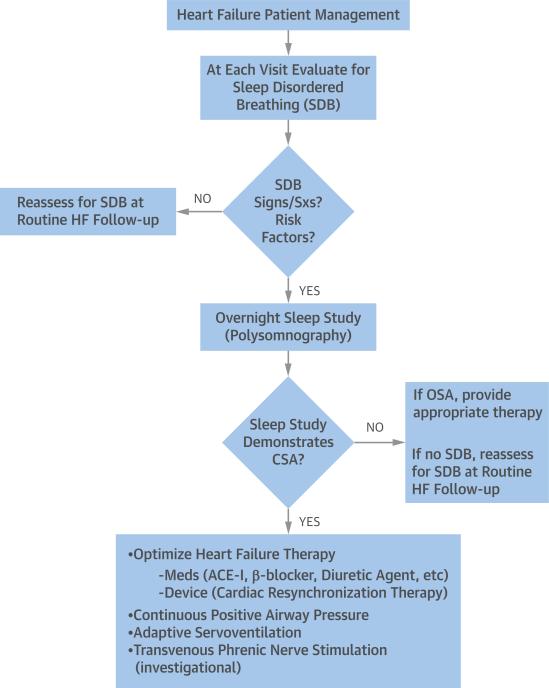

Because CSA often persists despite aggressive treatment of HF, targeted treatment for CSA must be considered. It is important to note that, presently, guidelines offer no consensus regarding the optimal treatment strategy for CSA in patients with HF (Table 1). A number of different therapies have been investigated, and although several have been shown to be of some benefit in reducing CSA or its symptoms, none have proved curative. Also lacking for most proposed therapies are large-scale, prospective, randomized trials establishing their safety and efficacy. Thus, current treatment strategies focus on either improving HF or reducing CSA itself (Figure 2).

TABLE 1.

Central Sleep Apnea and Guidelines

| Organization(s), Year (Ref. #) | CSA Treatment Guidelines |

|---|---|

| American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2011 (124) | 4.2.1.a CPAP therapy targeted to normalize the AHI is indicated for the initial treatment of CSAS related to CHF. (STANDARD) 4.2.2.a BPAP therapy in an ST mode targeted to normalize the AHI may be considered for the treatment of CSAS related to CHF only if there is no response to adequate trials of CPAP, ASV, and oxygen therapies. (OPTION) 4.2.3a ASV targeted to normalize the AHI is indicated for the treatment of CSAS related to CHF. (STANDARD) 4.2.4. Nocturnal oxygen therapy is indicated for the treatment of CSAS related to CHF. (STANDARD) 4.2.6.a The following therapies have limited supporting evidence but may be considered for the treatment of CSAS related to CHF, after optimization of standard medical therapy, if PAP therapy is not tolerated, and if accompanied by close clinical follow-up: acetazolamide and theophylline. (OPTION) |

| American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association, 2013 (100) | 7.3.1.4. Treatment of Sleep Disorders: Recommendation Class IIa 1. Continuous positive airway pressure can be beneficial to increase LVEF and improve functional status in patients with HF and sleep apnea. (Level of Evidence: B) |

| European Society of Cardiology, 2012 (145) | 11.19 Sleep Disturbance and Sleep-Disordered Breathing Nocturnal oxygen supplementation, continuous positive airway pressure, bi-level positive airway pressure, and adaptive servo-ventilation may be used to treat nocturnal hypoxemia. |

| Heart Failure Society of America, 2010 (146) | 6.7 Continuous positive airway pressure to improve daily functional capacity and quality of life is recommended in patients with HF and obstructive sleep apnea documented by approved methods of polysomnography. (Strength of Evidence = B) |

AHI = apnea-hypopnea index; ASV = adaptive servo-ventilation; BPAP = bilevel positive airway pressure; CHF = congestive heart failure; CPAP = continuous positive airway pressure; CSA = central sleep apnea; CSAS = central sleep apnea syndrome; HF = heart failure; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; PAP = positive airway pressure; ST = spontaneous timed.

FIGURE 2. Practical CSA Management in Patients With Heart Failure.

Current treatment strategies for central sleep apnea (CSA) focus on either improving heart failure (HF) or reducing CSA itself. ACE-I = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; OSA = obstructive sleep apnea; SDB = sleep-disordered breathing; Sxs = symptoms.

NONINVASIVE VENTILATORY SUPPORT

Several modes of noninvasive ventilatory support have been investigated to treat CSA in HF. The most common and best studied of these is CPAP therapy. CPAP utilizes a tight-fitting nasal or facial mask attached to an electric blower that applies a constant positive pressure to the airway to maintain patency. It has proven highly effective in treating OSA, for which it is the primary therapeutic modality (4,104). In HF patients with CSA, early, small, short-duration trials of CPAP showed a number of positive effects, including a reduction in central apnea/hypopnea events, ventricular ectopic beats, and nocturnal urinary and daytime plasma norepinephrine levels; an improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and QOL; and a trend toward a reduction in mortality and need for cardiac transplantation (16,52,105,106).

The CANPAP (Canadian Positive Airway Pressure Trial for Patients with Congestive Heart Failure and Central Sleep Apnea) was performed to better evaluate the potential of CPAP for the treatment of CSA in HF (107). CANPAP was a large, prospective, multi-center study that randomized 258 optimally-treated HF patients with an LVEF <40% and CSA with an AHI >15 events/h to receive either CPAP or no CPAP. The primary endpoint of the trial was transplant-free survival. Secondary endpoints included the effects of CPAP on LVEF, QOL, exercise tolerance, number of hospitalizations, and plasma levels of norepinephrine and atrial natriuretic peptide.

Results from CANPAP were mixed. On average, the AHI was reduced from 40 to 19 events/h after 3 months of CPAP therapy, and this reduction was associated with improved nocturnal oxygenation, exercise tolerance, and LVEF as well as lower plasma norepinephrine levels. However, CPAP did not demonstrate any effect on the primary endpoint: transplant-free survival. Additionally, there was an early divergence in survival rates that suggested early worse outcomes in the CPAP-treated group. After a mean follow-up of 2 years, however, the primary outcome was identical in the treated and control groups.

The CANPAP trial experienced a number of limitations that made its results difficult to interpret. Key among them: poor patient compliance with CPAP therapy, which, after 1 year, was being used for only 3.6 h/night. Another important issue was that CPAP therapy did not adequately suppress CSA in 43% of the study patients. This finding raised the question of whether the failure of CPAP to more completely reverse CSA during the trial may have been the reason why the study failed to meet its primary endpoint. To evaluate this possibility, a post-hoc analysis of the CANPAP data was performed (108). Study patients were stratified into 3 groups: control subjects; those treated with CPAP with suppression of CSA to an AHI <15 events/h; and those treated with CPAP without suppression of CSA (AHI >15 events/h). In the 57% of CANPAP patients who had CPAP reduce the AHI to <15 events/h, transplant-free survival was significantly increased compared with the control group (no CPAP), whereas among the 43% of CANPAP patients where CPAP did not reduce the AHI to <15 events/h, the transplant-free survival did not differ from that of the control group. These results appeared to confirm the hypothesis that adequate suppression of CSA might lead to improved transplant-free survival.

Overall, CPAP therapy has been shown to afflict unpredictable and, in some cases, adverse effects on HF patients with CSA. It has been suggested that, because CPAP increases intrathoracic pressure, it may cause adverse effects on both right and left ventricular pre-load and afterload that ultimately worsen rather than improve cardiac function (109). It has also been proposed that these adverse hemodynamic effects may have contributed to the early mortality of the treatment cohort in the CANPAP trial (109).

Because of poor patient compliance and the variable effects with CPAP therapy, a newer and potentially better-tolerated and effective type of noninvasive ventilatory support, called adaptive pressure support servo-ventilation (ASV), has been developed and is currently undergoing clinical trials. ASV was designed to address several aspects of the respiratory disturbance associated with CSA, including ventilatory overshoot and undershoot. Like CPAP, ASV delivers a baseline continuous positive airway pressure; however, ASV devices also are equipped with sensors that can detect central apneas and deliver several breaths at the tidal volume and respiratory rate previously determined to match the patient's minute ventilation during stable breathing. The goal of ASV therapy is to prevent the increase in PaCO2 during apnea and the hyperventilation that follows, thereby breaking the periodic breathing cycle.

Research suggests that ASV may be better tolerated than CPAP (110,111), which is likely due to its use of ventilation algorithms that provide different levels of pressure support on the basis of the type of sleep-disordered breathing detected by the device. This results in greater regulation of the amount of airflow delivered to the patient, making the therapy more comfortable than CPAP. Nonetheless, the patient still must wear a mask, which may be difficult for those who are short of breath or have orthopnea at baseline. Small studies of ASV have shown it to be more effective than CPAP in reducing CSA in HF (110,111). Additionally, these small studies demonstrated that ASV improves LVEF, sleep quality, and QOL. Large, multinational trials are currently underway to see if ASV will also improve morbidity and mortality in HF patients with CSA (112,113).

NOCTURNAL OXYGEN SUPPLEMENTATION

Supplemental nocturnal oxygen therapy at 2 to 4 l/min by nasal cannula has been used to treat CSA in patients with HF. Data from a number of small, short-term studies have shown that it improves the AHI (114–122), exercise capacity (117), and LVEF (114,118,123,124), and reduces serum B-type natriuretic peptide levels (119) and sympathetic nervous system activity (116,123). However, it does not appear to improve daytime sleepiness or cognitive function (116) or to have any consistent effect on QOL or sleep quality (115,116,120).

Research comparing nocturnal oxygen therapy to CPAP or ASV suggests that it confers no outcomes advantage over either therapy (108,125,126). Furthermore, unlike CPAP and ASV, nocturnal oxygen therapy is not effective in eliminating upper airway obstruction that may accompany central apneas. Given these findings, its use is likely best reserved for those patients whose pressure support therapies are found to be ineffective or are poorly tolerated.

NOCTURNAL SUPPLEMENTAL CARBON DIOXIDE

Considering the critical role hypocapnia plays in the development of CSA in HF, the use of nocturnal supplemental carbon dioxide administered by nasal cannula has been investigated as a potential treatment. Small, overnight trials have demonstrated that inhaled carbon dioxide significantly decreases the AHI, but does not improve sleep quality or reduce the number of arousals from sleep (127–130).

In addition to a lack of long-term data regarding its efficacy, supplemental carbon dioxide inhalation is difficult to safely implement in an unsupervised outpatient setting. Andreas et al. (130) also provide evidence that inhaled carbon dioxide may adversely affect sympathetic nervous system activity, which would negate any positive effects it might have on CSA. Thus, supplemental carbon dioxide is not currently recommended to treat CSA in HF.

CARDIAC PACING

Both cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) and atrial overdrive pacing have been studied for their effect on CSA in patients with HF. It is well established that CRT reduces morbidity and mortality associated with symptomatic HF, and current HF treatment guidelines recommend that it be offered to patients with an LVEF of ≤35%, a wide QRS complex (≥120 ms), and LV dilation (100). In small studies of CRT-indicated HF patients with documented CSA and who received a CRT device, CRT reduced CSA (131–135) and improved sleep quality (135). It is presumed that the associated increase in cardiac output is responsible for its beneficial effects in HF patients with CSA. However, further long-term, prospective, randomized trials are needed to confirm these results. In addition, CRT is restricted in professional practice guidelines to only a subset of HF patients with documented prolongation of the QRS and LV systolic dysfunction (100). These indications limit the potential applicability of CRT to treat CSA in HF patients with a short QRS duration or preserved LVEF.

Another approach, atrial overdrive pacing, which paces the heart at a rate higher than the mean intrinsic atrial rate, has also been investigated in HF patients with CSA. It has been hypothesized that by increasing the nocturnal heart rate, atrial overdrive pacing might increase cardiac output and reduce pulmonary congestion, therefore reducing or preventing CSA occurrence. In several small studies, atrial overdrive pacing was shown to reduce the number of episodes of CSA, improve blood oxygen saturation, and decrease arousals in patients with HF (136,137). One study, however, failed to find any improvement in CSA with atrial overdrive pacing (138). Its effect also appears small when compared to that of CRT. In a single-blind, randomized, crossover study evaluating the combined therapeutic impact of atrial overdrive pacing and CRT on CSA in HF, CRT alone was shown to significantly improve CSA, whereas CRT plus atrial overdrive pacing produced only a small, incremental improvement in CSA (additional reduction in the AHI by 2 events/h) (139).

THEOPHYLLINE AND ACETAZOLAMIDE

Theophyl-line, a respiratory and cardiac stimulant, has been suggested for the treatment of CSA in HF. In 1 small, short-term, double-blind, crossover study in stable HF patients with CSA, theophylline reduced the severity of CSA and oxygen desaturation during the night, but it did not improve LVEF (140). Overall, the cardiostimulatory and arrhythmogenic effects of theophylline limit its use in clinical practice until adequately-powered studies can demonstrate its long-term safety and efficacy in the HF population.

A mild diuretic agent that causes metabolic acidosis, acetazolamide also has been proposed to treat CSA in patients with HF. The metabolic acidosis induced by acetazolamide has been shown to decrease PaCO2 and thus increase the amount of PaCO2 needed to reach the apneic threshold, which may decrease the likelihood of developing CSA (141,142). In a small, short, double-blind, prospective trial in HF patients with CSA, acetazolamide was shown to decrease respiratory events, reduce the severity of nocturnal oxygen desaturation, and improve subjective sleep quality compared with placebo. However, there were no changes in objective measures of sleep quality and LVEF (142). Use of acetazolamide in patients with HF is complicated by the potential for urinary potassium wasting, leading to hypokalemia and increased risk of arrhythmia. Thus, use of this agent to treat CSA in HF awaits larger, longer-term studies of its overall safety and efficacy.

PHRENIC NERVE STIMULATION

Recently, a new investigational treatment for CSA has been introduced utilizing a totally implantable, lead-based system that provides unilateral transvenous stimulation of the phrenic nerve to regulate breathing. As a totally implantable, device-based therapy, it may be better tolerated than CPAP or ASV in HF patients. Additionally, the device initiates and terminates therapy automatically without patient intervention and thus should improve patient adherence to treatment.

Early clinical experience with this technology has been encouraging. In 1 small, multicenter pilot study (143), HF patients with documented CSA by polysomnography underwent acute placement of a neurostimulation lead into either the right brachiocephalic vein or the left pericardiophrenic vein. Patients then underwent polysomnography over 2 nights to compare sleep characteristics during a control night (no phrenic stimulation) with a therapy night (phrenic stimulation during episodes of CSA). Overall, therapy resulted in significant improvement in major indexes of CSA severity, including the AHI, central apnea index, 4% oxygen desaturation index, and arousal index. More recently, in a prospective, international, multicenter, nonrandomized trial involving a broad population of patients with CSA, unilateral transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation resulted in a 56% decrease in the AHI, and other sleep-disordered breathing parameters improved as well. Favorable effects on sleepiness were also noted. The therapy was found to be well tolerated, and therapeutic efficacy was maintained at 6-month follow-up (144). Active research of phrenic nerve stimulation for the treatment of CSA is currently ongoing to further evaluate its safety and efficacy.

CONCLUSIONS

CSA is now recognized as an important, independent risk factor for worsening HF and reduced survival in patients with HF. Unfortunately, CSA is often not identified by clinicians, because its subtle findings often become lost in the signs and symptoms that typically accompany HF. A high index of suspicion for CSA should exist when an HF patient presents with the clinical features or risk factors of CSA, and in these patients, an overnight sleep study should be performed.

Research conducted over the past few decades has greatly expanded our understanding of causes and consequences of CSA in HF. Oscillation of the PaCO2 above and below apneic threshold appears to play a central role in CSA development, although other factors, including diminished cerebrovascular response to changes in CO2, upper airway instability, and increased circulation time (due to decreased cardiac output), likely also contribute. The adverse consequences of CSA in HF that arise from the repeated episodes of apnea, hypoxia, reoxygenation, and arousal throughout the night are multiple and include sympathetic nervous system activation, oxidative stress, systemic inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction. All of these pathologic effects are known to significantly contribute to worsening cardiac function in patients with HF.

Because CSA often manifests due to advanced or worsening HF, optimizing medical therapy and, when appropriate, using device-based therapy (e.g., CRT), are of foremost importance. Research has shown that once HF is clinically improved, CSA often improves as well. In cases where CSA persists despite aggressive treatment of HF, other therapeutic interventions, such as CPAP or supplemental oxygen therapy, should be considered. Both CPAP and nocturnal oxygen supplementation have been shown to reduce episodes of CSA, improve cardiac function and exercise capacity, and reduce sympathetic activity. However, neither therapy has been shown to reduce mortality, and adherence to CPAP therapy remains a significant problem.

More recently, ASV has been introduced to address the shortcomings of CPAP therapy, with early experience suggesting that ASV may be better tolerated than CPAP and more effective in reducing CSA in HF. Whether it confers any mortality benefit is still being investigated. Phrenic nerve stimulation also may offer a promising new way to treat CSA in HF. Early data indicate that it significantly improves major indexes of CSA severity. Furthermore, as a totally implantable, device-based therapy, patient adherence is not an issue. Large-scale, long-term, randomized, controlled trials are still needed, however, to further evaluate its potential clinical impact.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Janice Hoettels, PA, MBA, for her assistance with the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding was provided by Respicardia, Inc. Drs. Costanzo, Ponikowski, Augostini, and Stell- brink are clinical investigators and steering committee members for Respicardia, Inc. Dr. Khayat and Mr. Mianulli are consultants to Respicardia. Dr. Ponikowski has served as a consultant for Coridea. Dr. Abraham is a clinical investigator and consultant for Respicardia, Inc.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- AHI

apnea-hypopnea index

- ASV

adaptive pressure support servo-ventilation

- CPAP

continuous positive airway pressure

- CRT

cardiac resynchronization therapy

- CSA

central sleep apnea

- HF

heart failure

- LVEF

left ventricular ejection fraction

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-kappa B

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

REFERENCES

- 1.Javaheri S. Sleep disorders in systolic heart failure: a prospective study of 100 male patients. The final report. Int J Cardiol. 2006;106:21–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.12.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacDonald M, Fang J, Pittman SD, et al. The current prevalence of sleep disordered breathing in congestive heart failure patients treated with beta-blockers. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:38–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oldenburg O, Lamp B, Faber L, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in patients with symptomatic heart failure: a contemporary study of prevalence in and characteristics of 700 patients. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;9:251–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Somers VK, White DP, Amin R, et al. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: an American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council, and Council on Cardiovascular Nursing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:686–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley TD, Floras JS. Sleep apnea and heart failure: part I: obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation. 2003;107:1671–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000061757.12581.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo P., Jr Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:263–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jenkinson C, Davies RJ, Mullins R, Stradling JR. Comparison of therapeutic and subtherapeutic nasal continuous positive airway pressure for obstructive sleep apnoea: a randomized prospective parallel trial. Lancet. 1999;353:2100–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10532-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montserrat JM, Ferrer M, Hernandez L, et al. Effectiveness of CPAP treatment in daytime function in sleep apnea syndrome: a randomized controlled study with an optimized placebo. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:608–13. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.2006034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Findley L, Smith C, Hooper J, Dineen M, Suratt PM. Treatment with nasal CPAP decreases automobile accidents in patients with sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:857–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.3.9812154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Somers VK, Dyken ME, Clary MP, Abboud FM. Sympathetic neural mechanisms in obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1897–904. doi: 10.1172/JCI118235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campos-Rodriguez F, Pena-Grinan N, Reves-Nunez N, et al. Mortality in obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea patients treated with positive airway pressure. Chest. 2005;128:624–33. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.2.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez-Garcia M-A, Campos-Rodriguez F, Catalan-Serra P, et al. Cardiovascular mortality in obstructive sleep apnea in the elderly: role of long-term continuous positive airway pressure treatment. A prospective observational study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:909–16. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0448OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Javaheri S, Dempsey JA. Central sleep apnea. Compr Physiol. 2013;3:141–63. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c110057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naughton MT, Benard DC, Liu PP, Rutherford R, Rankin F, Bradley TD. Effects of nasal CPAP on sympathetic activity in patients with heart failure and central sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;152:473–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.2.7633695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bitter T, Westerheide N, Prinz C, et al. Cheyne-Stokes respiration and obstructive sleep apnoea are independent risk factors for malignant ventricular arrhythmias requiring appropriate cardioverter-defibrillator therapies in patients with congestive heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:61–74. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naughton MT, Liu PP, Bernard DC, Goldstein RS, Bradley TD. Treatment of congestive heart failure and Cheyne-Stokes respiration during sleep by continuous positive airway pressure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:92–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.1.7812579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanly P, Zuberi-Khokhar N. Daytime sleepiness in patients with congestive heart failure and Cheyne-Stokes respiration. Chest. 1995;107:952–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.107.4.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Javaheri S, Parker TJ, Liming JD, et al. Sleep apnea in 81 ambulatory male patients with stable heart failure. Types and their prevalences, consequences, and presentations. Circulation. 1998;97:2154–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.21.2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sin DD, Fitzgerald F, Parker JD. Risk factors for central and obstructive sleep apnea in 450 men and women with congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:1101–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.4.9903020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calvin AD, Somers VK, van der Walt C, Scott CG, Olson LJ. Relation of natriuretic peptide concentrations to central sleep apnea in patients with heart failure. Chest. 2011;140:1517–23. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khayat R, Small R, Rathman L, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing in heart failure: identifying and treating an important but often unrecognized comorbidity in heart failure patients. J Cardiac Fail. 2013;19:431–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force Sleep-related breathing disorders in adults: recommendations for syndrome definition and measurement techniques in clinical research. The report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Task Force. Sleep. 1999;22:667–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jilek C, Krenn M, Sebah D, et al. Prognostic impact of sleep disordered breathing and its treatment in heart failure: an observational study. Eur J Heart Fail. 2011;13:68–75. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfq183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Javaheri S, Shukula R, Ziegler H, Wexler L. Central sleep apnea, right ventricular dysfunction, and low diastolic blood pressure are predictors of mortality in systolic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2028–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naughton M, Benard D, Tam A, Rutherford R, Bradley TD. Role of hyperventilation in the pathogenesis of central sleep apneas in patients with congestive heart failure. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1993;148:330–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/148.2.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanly P, Zuberi N, Gray R. Pathogenesis of Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients with congestive heart failure: relationship to arterial PCO2. Chest. 1993;104:1079–84. doi: 10.1378/chest.104.4.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dempsey JA. Crossing the apnoeic threshold: causes and consequences. Exp Physiol. 2005;90:13–24. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2004.028985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cherniack NS. Respiratory dysrhythmias during sleep. New Engl J Med. 1981;305:325–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198108063050606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caruana-Montaldo B, Gleeson K, Zwillich CW. The control of breathing in clinical practice. Chest. 2000;117:205–25. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.1.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quaranta AJ, D'Alonzo GE, Krachman SL. Cheyne-Stokes respiration during sleep in congestive heart failure. Chest. 1997;111:467–73. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.2.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lorenzi-Filho G, Genta PR, Figueiredo AC, Inoue D. Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients with congestive heart failure: causes and consequences. Clinics. 2005;60:333–44. doi: 10.1590/s1807-59322005000400012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xie A, Skatrud JB, Puleo DS, Rahko PS, Dempsey JA. Apnea-hypopnea threshold for CO2 in patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:1245–50. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200110-022OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu J, Zhang F, Fletcher EC. Stimulation of breathing by activation of pulmonary peripheral afferents in rabbits. J Appl Physiol. 1998;85:1485–92. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.4.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Solin P, Bergin P, Richardson M, Kaye DM, Walters EH, Naughton MT. Influence of pulmonary capillary wedge pressure on central apnea in heart failure. Circulation. 1999;99:1574–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.12.1574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lorenzi-Filho G, Azevedo ER, Parker JD, Bradley TD. Relationship of carbon dioxide tension in arterial blood to pulmonary wedge pressure in heart failure. Eur Respir J. 2002;19:37–40. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00214502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.White LH, Bradley TD. Role of nocturnal rostral fluid shift in the pathogenesis of obstructive and central sleep apnea. J Physiol. 2013;591:1179–93. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.245159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Solin P, Roebuck T, Johns DP, Walters EH, Naughton MT. Peripheral and central ventilatory responses in central sleep apnea with and without congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:2194–200. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.2002024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Javaheri S. A mechanism of central sleep apnea in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:949–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909233411304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alex CG, Onal E, Lopata M. Upper airway occlusion during sleep in patients with Cheyne-Stokes respiration. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;133:42–5. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1986.133.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Badr MS, Toiber F, Skatrud JB, Dempsey J. Pharyngeal narrowing/occlusion during central sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol. 1995;78:1806–15. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1995.78.5.1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leung RST, Bradley TD. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:2147–65. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.12.2107045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hall MJ, Xie A, Rutherford R, Ando S, Floras JS, Bradley TD. Cycle length of periodic breathing in patients with and without heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:376–81. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.2.8756809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xie A, Skatrud JB, Khayat R, Dempsey JA, Morgan B, Russell D. Cerebrovascular response to carbon dioxide in patients with congestive heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:371–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-807OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spaak J, Egri ZJ, Kubo T, et al. Muscle sympathetic nerve activity during wakefulness in heart failure patients with and without sleep apnea. Hypertension. 2005;46:1327–32. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000193497.45200.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pepper GS, Lee RW. Sympathetic activation in heart failure and its treatment with β-blockade. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:225–34. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.3.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brunner-La Rocca HP, Esler MD, Jennings GL, Kaye DM. Effect of cardiac sympathetic nervous activity on mode of death in congestive heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:1136–43. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaye DM, Lefkovits J, Jennings GL, Bergin P, Broughton A, Esler MD. Adverse consequences of high sympathetic nervous activity in the failing heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26:1257–63. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00332-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cohn JN, Levine TB, Olivari MT, et al. Plasma norepinephrine as a guide to prognosis in patients with chronic congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:819–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198409273111303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van de Borne P, Oren R, Abouassaly C, et al. Effect of Cheyenne-Stokes respiration on muscle sympathetic nerve activity in severe congestive heart failure secondary to ischemic or idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:432–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00936-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Triposkiadis F, Karayannis G, Giamouzis G, Skoularigis J, Louridas G, Butler J. The sympathetic nervous system in heart failure: physiology, pathophysiology, and clinical implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1747–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leung RS, Diep TM, Bowman ME, Lorenzi-Filho G, Bradley TD. Provocation of ventricular ectopy by Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients with heart failure. Sleep. 2004;27:1337–43. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.7.1337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Javaheri S. Effects of continuous positive airway pressure on sleep apnea and ventricular irritability in patients with heart failure. Circulation. 2000;101:392–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.4.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sano K, Watanabe E, Hayano J, et al. Central sleep apnoea and inflammation are independently associated with arrhythmia in patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:1003–10. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seddon M, Looi YH, Shah AM. Oxidative stress and redox signaling in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Heart. 2007;93:903–7. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.068270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsutsui H, Kinugawa S, Matsushima S. Oxidative stress and heart failure. Am J Physiol Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H2181–90. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00554.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lavie L, Lavie P. Molecular mechanisms of cardiovascular disease in OSAHS: the oxidative stress link. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:1467–84. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00086608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McCord JM. Oxygen-derived free radicals in postischemic tissue injury. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:159–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501173120305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dean RT, Wilcox I. Possible atherogenic effects of hypoxia during obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 1993;16:S15–21. doi: 10.1093/sleep/16.suppl_8.s15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lavie L. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome-an oxidative disorder. Sleep Med Rev. 2003;7:35–51. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Suzuki YJ, Jain V, Park A-M, Day RM. Oxidative stress and oxidant signaling in obstructive sleep apnea and associated cardiovascular diseases. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:1683–92. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prabhakar NR. Sleep apneas. An oxidative stress? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:859–60. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.7.2202030c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Levy P, Pepin J-L, Arnaud C, et al. Intermittent hypoxia and sleep-disordered breathing: current concepts and perspectives. Eur Resp J. 2008;32:1082–95. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00013308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khayat R, Patt B, Hayes D. Obstructive sleep apnea: the new cardiovascular disease. Part I: obstructive sleep apnea and the pathogenesis of vascular disease. Heart Fail Rev. 2009;14:143–53. doi: 10.1007/s10741-008-9112-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Christou K, Markoulis N, Moulas AN, Pastaka C, Gourgouliania KI. Reactive oxygen metabolites (ROMs) as an index of oxidative stress in obstructive sleep apnea patients. Sleep Breath. 2003;7:105–10. doi: 10.1007/s11325-003-0105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barcelo A, Miralles C, Barbe F, Vila M, Pons S, Agusti AG. Abnormal lipid peroxidation in patients with sleep apnea. Eur Respir J. 2000;16:644–7. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16d13.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Carpagnano GE, Kharitonov SA, Resta O, Foschino-Barbaro MP, Gramiccioni E, Barnes PJ. Increased 8-isoprostane and interleukin-6 in breath condensate of obstructive sleep apnea patients. Chest. 2002;122:1162–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.4.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lavie L, Vishnevsky A, Lavie P. Evidence for lipid peroxidation in obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2004;27:123–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tan KC, Chow WS, Lam JC, et al. HDL dysfunction in obstructive sleep apnea. Atherosclerosis. 2006;184:377–82. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Christou K, Moulas AN, Pastaka C, Gourgouliania KI. Antioxidant capacity in obstructive sleep apnea patients. Sleep Med. 2003;4:225–8. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(02)00253-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jung HH, Han H, Lee JH. Sleep apnea, coronary artery disease, and antioxidant status in hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:875–82. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Carpagnano GE, Kharitonov SA, Resta O, Foschino-Barbaro MP, Gramiccioni E, Barnes PJ. 8-isoprostane, a marker of oxidative stress, is increased in exhaled breath condensate of patients with obstructive sleep apnea after night and is reduced by continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Chest. 2003;124:1386–92. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.4.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Christou K, Kostikas K, Pastaka C, Tanou K, Antoniadou I, Gourgoulianis KI. Nasal continuous positive pressure treatment reduces systemic oxidative stress in patients with severe obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep Med. 2009;10:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Biasucci L, Vitelli G, Liuzzo S, et al. Elevated levels of interleukin 6 in unstable angina. Circulation. 1996;94:874–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.5.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Neumann FJ, Ott I, Gawaz M, et al. Cardiac release of cytokines and inflammatory responses in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1995;92:748–55. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.4.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Levine B, Kalman J, Mayer L, Fillit H, Packer M. Elevated circulating levels of tumor necrosis factor in severe chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:236–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199007263230405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Oral H, Kapadia M, Nakano G, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-a and the failing human heart. Clin Cardiol. 1995;18:S2–7. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960181605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Torre-Amione G, Kapadia S, Benedict C, Oral H, Young JB, Mann DL. Proinflammatory cytokine levels in patients with depressed left ventricular ejection fraction: a report from the studies of left ventricular dysfunction (SOLVD). J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1201–6. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00589-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mann DL. Inflammatory mediators and the failing heart: past, present, and the foreseeable future. Circ Res. 2002;91:988–98. doi: 10.1161/01.res.0000043825.01705.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Rauchhaus M, Doehner W, Francis DP, et al. Plasma cytokine parameters and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2000;102:3060–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.25.3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Deswal A, Petersen NJ, Feldman AM, Young JB, White BG, Mann DL. Cytokines and cytokine receptors in advanced heart failure: an analysis of the cytokine database from the Vesnarinone trial (VEST). Circulation. 2001;103:2055–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.16.2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ciftci TU, Kokturk O, Bukan N, Bilgihan A. The relationship between serum cytokine levels with obesity and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Cytokine. 2004;28:87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dyugovskaya L, Lavie P, Lavie L. Increased adhesion molecules expression and production of reactive oxygen species in leukocytes of sleep apnea patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:934–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.7.2104126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schulz R, Mahmoudi S, Hattar K, et al. Enhanced release of superoxide from polymorphonuclear neutrophils in obstructive sleep apnea. Impact of continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162:566–70. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.2.9908091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ryan S, Taylor CT, McNicholas WT. Selective activation of inflammatory pathways by intermittent hypoxia in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Circulation. 2005;112:2660–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.556746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ryan S, Taylor CT, McNicholas WT. Systemic inflammation: a key factor in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular complications in obstructive sleep apnea? Thorax. 2009;64:631–6. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.105577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gordon JW, Shaw JA, Kirshenbaum LA. Multiple facets of NF-kB in the heart: To be or not to NF-κB. Circ Res. 2011;108:1122–32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.226928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Htoo AK, Greenberg H, Tongia S, et al. Activation of nuclear factor kB in obstructive sleep apnea: a pathway leading to systemic inflammation. Sleep Breath. 2006;10:43–50. doi: 10.1007/s11325-005-0046-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Greenberg H, Ye X, Wilson D, Htoo AK, Hendersen T, Liu SF. Chronic intermittent hypoxia activates nuclear factor-kappaB in cardiovascular tissues in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;343:591–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Verma S, Anderson TJ. Fundamentals of endothelial function for the clinical cardiologist. Circulation. 2002;105:546–9. doi: 10.1161/hc0502.104540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brunner H, Cockcroft JR, Denfield J, et al. Endothelial function and dysfunction. Part II: Association with cardiovascular risk factors and diseases. A statement by the Working Group on Endothelins and Endothelial Factors of the European Society of Hypertension. J Hypertens. 2005;23:233–46. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200502000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Flammer AJ, Anderson T, Celermajer DS, et al. The assessment of endothelial function-from research into clinical practice. Circulation. 2012;126:753–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.093245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Endemann DH, Schiffrin EL. Endothelial dysfunction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1983–92. doi: 10.1097/01.ASN.0000132474.50966.DA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bauersachs J, Widder JD. Endothelial dysfunction in heart failure. Pharmacol Rep. 2008;60:119–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lopez Farre A, Casado S. Heart failure, redox alterations, and endothelial dysfunction. Hypertension. 2001;38:1400–5. doi: 10.1161/hy1201.099612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Koppenol WH, Moreno JJ, Pryor WA, Ischiropoulos H, Beckman JS. Peroxynitrite, a cloaked oxidant formed by nitric oxide and su-peroxide. Chem Res Toxicol. 1992;5:834–42. doi: 10.1021/tx00030a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lui MM, Lam DC, Ip MS. Significance of endothelial dysfunction in sleep-related breathing disorder. Respirology. 2013;18:39–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Dark DS, Pingleton SK, Kerby GR, et al. Breathing pattern abnormalities and arterial oxygen desaturation during sleep in congestive heart failure syndrome: improvement following medical therapy. Chest. 1987;91:833–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.91.6.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Walsh JT, Andrews R, Starling R, Cowley AJ, Johnston ID, Kinnear WJ. Effects of captopril and oxygen on sleep apnoea in patients with mild to moderate congestive heart failure. Br Heart J. 1995;73:237–41. doi: 10.1136/hrt.73.3.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Baylor P, Tayloe D, Owen D, Sander C. Cardiac failure presenting as sleep apnea. Elimination of apnea following medical management of cardiac failure. Chest. 1988;94:1298–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.94.6.1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:147–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ribiero JP, Knutzen A, Rocco MB, et al. Periodic breathing during exercise in severe heart failure. Reversal with milrinone or cardiac transplantation. Chest. 1987;92:555–6. doi: 10.1378/chest.92.3.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Braver HM, Brandes WC, Kubiet MA, et al. Effect of cardiac transplantation on Cheyne-Stokes respiration occurring during sleep. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76:632–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80174-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mansfield DR, Solin P, Roebuck T, et al. The effect of successful heart transplant treatment of heart failure on central sleep apnea. Chest. 2003;124:1675–81. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.5.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Basner RC. Continuous positive airway pressure for obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1751–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct066953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tkacova R, Liu PP, Naughton MT, et al. Effect of continuous positive airway pressure on mitral regurgitant fraction and atrial natriuretic peptide in patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;30:739–45. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sin D, Logan A, Fitzgerald F, et al. Effects of continuous positive airway pressure on cardiovascular outcomes in heart failure patients with and without Cheyne-Stokes respiration. Circulation. 2000;102:61–6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bradley TD, Logan AG, Kimoff RJ, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure for central sleep apnea and heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2025–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Arzt M, Floras JS, Logan AG, et al. Suppression of central sleep apnea by continuous positive airway pressure and transplant-free survival in heart failure: a post hoc analysis of the Canadian Positive Airway Pressure for Patients with Central Sleep Apnea and Heart Failure Trial (CANPAP). Circulation. 2007;115:3173–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Javaheri S. CPAP should not be used for central sleep apnea in congestive heart failure. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2:399–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Philippe C, Stoica-Herman M, Drouot X, et al. Compliance with and effectiveness of adaptive servoventilation versus continuous positive airway pressure in the treatment of Cheyne-Stokes respiration in heart failure over a six month period. Heart. 2006;92:337–42. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.060038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Teschler H, Dohring J, Wang YM, Berthon-Jones M. Adaptive pressure support servo-ventilation: a novel treatment for Cheyne-Stokes respiration in heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:614–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.9908114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cowie MR, Woehrle H, Wegscheider K, et al. Rationale and design of the SERVE-HF study: treatment of sleep-disordered breathing with predominant central sleep apnoea with adaptive servo-ventilation in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2013;15:937–43. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hft051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. [May 28, 2014];Effect of adaptive servo ventilation (ASV) on survival and hospital admissions in heart failure (ADVENT-HF) Available at: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01128816.

- 114.Sasayama S, Izumi T, Seino Y, Ueshima K, Asanoi H. Effects of nocturnal oxygen therapy on outcome measures in patients with chronic heart failure and Cheyenne-Stokes respiration. Circ J. 2006;70:1–7. doi: 10.1253/circj.70.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hanly P, Millar T, Steljes D, Baert R, Frais M, Kryger M. The effect of oxygen on respiration and sleep in patients with congestive heart failure. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:777–82. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-10-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Staniforth A, Kinnear W, Starling R, Hetmanski D, Cowley A. Effect of oxygen on sleep quality, cognitive function, and sympathetic activity in patients with chronic heart failure and Cheyne-Stokes respiration. Eur Heart J. 1998;19:922–8. doi: 10.1053/euhj.1997.0861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Andreas S, Clemens C, Sandholzer H, Figulla H, Kreuzer H. Improvement of exercise capacity with treatment of Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients with congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27:1486–90. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sasayama S, Izumi T, Matsuzaki M, et al. Improvement of quality of life with nocturnal oxygen therapy in heart failure patients with central sleep apnea. Circ J. 2009;73:1255–62. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-08-1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Shigemitsu M, Nishio K, Kusuyama T, Itoh S, Konno N, Katagiri T. Nocturnal oxygen therapy prevents progress of congestive heart failure with central sleep apnea. Int J Cardiol. 2007;115:354–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Franklin K, Eriksson P, Sahlin C, Lundgren R. Reversal of central sleep apnea with oxygen. Chest. 1997;111:163–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Javaheri S, Ahmed M, Parker T, Brown C. Effects of nasal O2 on sleep-related disordered breathing in ambulatory patients with stable heart failure. Sleep. 1999;22:1101–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/22.8.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Krachman S, Nugent T, Crocetti J, D'Alonzo G, Chatila W. Effects of oxygen therapy on left ventricular function in patients with Cheyne-Stokes respiration and congestive heart failure. J Clin Sleep Med. 2005;1:271–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Toyama T, Seki R, Kasama S, et al. Effectiveness of nocturnal home oxygen therapy to improve exercise capacity, cardiac function and cardiac sympathetic nerve activity in patients with chronic heart failure and central sleep apnea. Circ J. 2009;73:299–304. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-07-0297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Aurora RN, Chowdhuri S, Ramar K, et al. The treatment of central sleep apnea syndromes in adults: practice parameters with an evidence-based literature review and meta-analyses. Sleep. 2012;35:17–40. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Krachman SL, D'Alonso GE, Berger TJ, Eisen HJ. Comparison of oxygen therapy with nasal continuous positive airway pressure on Cheyne-Stokes respiration during sleep in congestive heart failure. Chest. 1999;116:1550–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.6.1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Campbell AJ, Ferrier K, Neill AM. Effect of oxygen versus adaptive pressure support servo-ventilation in patients with central sleep apnoea-Cheyne-Stokes respiration and congestive heart failure. Intern Med J. 2012;42:1130–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2011.02623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Lorenzi-Filho G, Rankin F, Bies I, et al. Effects of inhaled carbon dioxide and oxygen on Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients with heart failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:1490–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.5.9810040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Steens RD, Millar TW, Su X, et al. Effects of inhaled 3% CO2 on Cheyne-Stokes respiration in congestive heart failure. Sleep. 1994;17:61–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/17.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Szollosi I, Jones M, Morrell MJ, et al. Effect of CO2 inhalation on central sleep apnea and arousals from sleep. Respiration. 2004;71:493–8. doi: 10.1159/000080634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Andreas S, Weidel K, Hagenah G, et al. Treatment of Cheyne-Stokes respiration with nasal oxygen and carbon dioxide. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:414–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12020414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kara T, Novak M, Nykodym J, et al. Effect of cardiac resynchronization therapy on sleep disordered breathing in patients with systolic heart failure. Chest. 2008;134:87–93. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Skobel EC, Sinha AM, Norra C, et al. Effect of cardiac resynchronization therapy on sleep quality, quality of life, and symptomatic depression in patients with chronic heart failure and Cheyne–Stokes respiration. Sleep Breath. 2005;9:159–66. doi: 10.1007/s11325-005-0030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Oldenburg O, Faber L, Vogt J, et al. Influence of cardiac resynchronisation therapy on different types of sleep disordered breathing. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9:820–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Gabor JY, Newman DA, Barnard-Roberts V, et al. Improvement in Cheyne–Stokes respiration following cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:95–100. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00093904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Sinha AM, Skobel EC, Breithardt OA, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy improves central sleep apnea and Cheyne-Stokes respiration in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:68–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Garrigue S, Bordier P, Jais P, et al. Benefit of atrial pacing in sleep apnea syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:404–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Weng CL, Chen Q, Ma YL, He QY. A meta-analysis of the effects of atrial overdrive pacing on sleep apnea syndrome. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2009;32:1434–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2009.02474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Luthje L, Unterberg-Buchwald C, Dajani D, Vollmann D, Hassesfuss G, Andreas S. Atrial overdrive pacing in patients with sleep apnea with implanted pacemaker. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:118–22. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1258OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Luthje L, Renner B, Kessels R, et al. Cardiac resynchronization therapy and atrial overdrive pacing for the treatment of central sleep apnoea. Eur Heart J. 2009;11:273–80. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfn042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Javaheri S, Parker TJ, Wexler L, et al. Effect of theophylline on sleep-disordered breathing in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:562–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608223350805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Nakayama H, Smith CA, Rodman JR, Skatrud JB, Dempsey JA. Effect of ventilatory drive on carbon dioxide sensitivity below eupnea during sleep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:1251–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2110041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Javaheri S. Acetazolamide improves central sleep apnea in heart failure. A double-blind, prospective study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:234–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200507-1035OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Ponikowski P, Javaheri S, Michalkiewicz D, et al. Transvenous phrenic nerve stimulation for the treatment of central sleep apnoea in heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:889–94. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]