Abstract

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) is mechanistically and therapeutically challenging, not only because of the molecular and cellular perturbations that generate vascular abnormalities, but also the modifications to circulatory physiology that result, and are likely to exacerbate vascular injury. First, most HHT patients have visceral arteriovenous malformations (AVMs). Significant visceral AVMs reduce the systemic vascular resistance: supra-normal cardiac outputs are required to maintain arterial blood pressure, and may result in significant pulmonary venous hypertension. Secondly, bleeding from nasal and gastrointestinal telangiectasia leads to iron losses of such magnitude that in most cases, diet is insufficient to meet the ‘hemorrhage adjusted iron requirement.’ Resultant iron deficiency restricts erythropoiesis, leading to anemia and further increases in cardiac output. Low iron levels are also associated with venous and arterial thromboses, elevated Factor VIII, and increased platelet aggregation to circulating 5HT (serotonin). Third, recent data highlight that reduced oxygenation of blood due to pulmonary AVMs results in a graded erythrocytotic response to maintain arterial oxygen content, and higher stroke volumes and/or heart rates to maintain oxygen delivery. Finally, HHT-independent factors such as diet, pregnancy, sepsis, and other intercurrent illnesses also influence vascular structures, hemorrhage, and iron handling in HHT patients. These considerations emphasize the complexity of mechanisms that impact on vascular structures in HHT, and also offer opportunities for targeted therapeutic approaches.

Keywords: anemia, cardiac output, hypoxia, hemorrhage, iron deficiency, paradoxical emboli, pulmonary hypertension, venous thromboemboli

Introduction

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT) results from a single mutation in a causative gene such as endoglin, ACVRL1 (encoding ALK-1), or SMAD4. The hallmark of HHT is the presence of arteriovenous malformations (AVMs), and smaller telangiectatic vessels. Additional phenotypic patterns are recognized in smaller numbers of patients (Shovlin, 2010; McDonald et al., 2011).

Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia severity is usually assessed with reference to:

• the presence of vascular abnormalities at particular sites;

• their severity (by anatomic or physiologic measurements);

• hemorrhage, and/or

• organ-specific consequences due to blood bypassing critical capillary beds.

Recent data have begun to illuminate a pattern of marked environmental modification of specific aspects of the HHT phenotype, for example in relation to blood flow, bleeding, and thromboses. Many ‘environmental’ modifiers can be consequences of the HHT phenotype itself.

This mini review focuses on secondary and tertiary consequences of HHT vascular structures. These contribute to the full clinico-pathologic spectrum of HHT, and are relevant to angiogenic, developmental, and injury considerations presented elsewhere in this series.

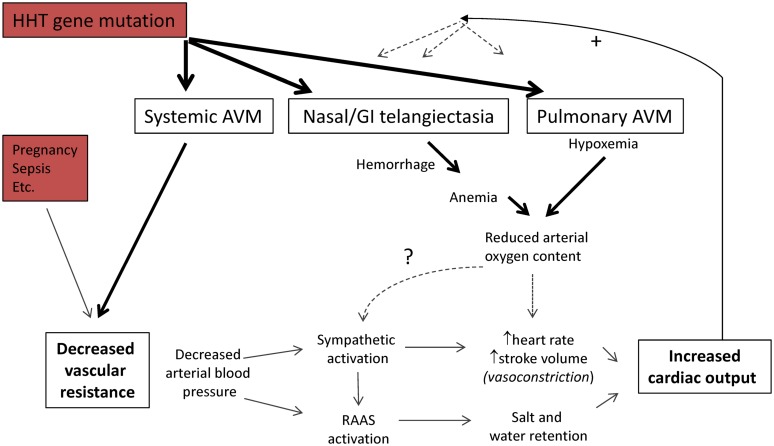

Systemic AVMs and Cardiac Output

Systemic AVMs are one of the classical pathologies associated with high cardiac output states (Mehta and Dubrey, 2009; Figure 1), when cardiac index (cardiac output/body surface area) exceeds 3.9 L/min/m2 (Anand and Florea, 2001). Reduced systemic vascular resistance due to the AVMs leads to a fall in arterial blood pressure. Resultant activation of sympathetic and neurohormonal systems increase cardiac output and maintain vital organ perfusion at the expense of salt and water retention (Anand and Florea, 2001; Mehta and Dubrey, 2009). The increases in cardiac output that are needed to preserve arterial blood pressure in the face of severe reductions in systemic vascular resistance may exceed the pump capacity of healthy hearts, leading to high output cardiac failure (Anand and Florea, 2001; Mehta and Dubrey, 2009). High left atrial filling pressures lead to pulmonary venous hypertension (Anand and Florea, 2001; Mehta and Dubrey, 2009).

FIGURE 1.

Pathophysiology of high cardiac output states. The cardiac output is the volume of blood ejected each minute by a ventricle, and the product of stroke volume, and heart rate/minute. Systemic vascular resistance is defined by . For further details of clinical states that reduce systemic vascular resistance, see Anand et al., 1993; Anand and Florea, 2001; Mehta and Dubrey, 2009. Abbreviations: RAAS, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system. Note the potential positive feedback loops influencing HHT vascular structures.

Relevance to the HHT Phenotype

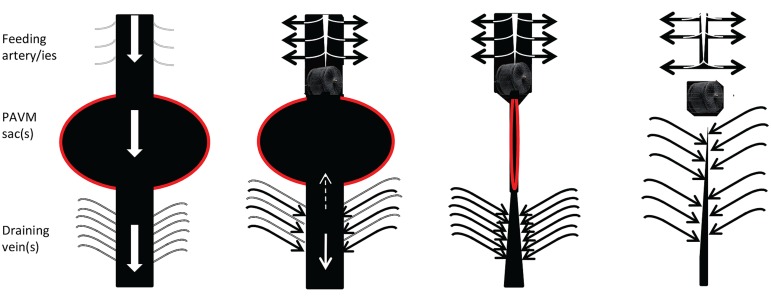

All vessels, including abnormal HHT vascular structures, adapt to the volume and pressure of blood flowing through them. HHT vessels do not behave normally, for example, AVMs do not display the usual adaptation to optimal arterial wall thickness/ lumen radius ratios to minimize wall stress (Owens, 2010). Within specific vascular beds, increased flow modifies vascular structures. In HHT, this is best exemplified by the dilated feeding arteries and draining veins associated with pulmonary AVMs (Figure 2). These regress once pulmonary AVMs are embolized and such regression is one of the hallmarks of successful obliteration of the PAVM sacs.

FIGURE 2.

Cartoon of usual behavior of macroscopic, discrete PAVMs pre and post embolization. (Left) Preferential blood flow through pulmonary arteriovenous malformation (AVM) sacs (red border) leads to reduced perfusion of non-PAVM associated arteries (gray), dilatation of feeding arteries that commonly appear as second or third order vessels; and dilatation/early filling of draining veins. Centre left: immediately following embolization of all feeding arteries, blood flow ceases through the pulmonary AVM, and is redirected to normal arteries. Surprisingly it appears very rare for sac thrombus to embolise before organization. Centre right and far right: over subsequent months, assuming feeding arteries remain occluded and the pulmonary AVM does not acquire new feeding arteries, organization, and remodeling leads to regression of the sac, and normalization of diameters of former feeding arteries/draining veins (For patient images, see Howard et al., 2014).

More widely, higher circulating blood volumes are predicted to impact on HHT vascular structures. Multiple HHT series and case reports indicate that in women with HHT, pregnancy can result in the development of new telangiectasia/AVMs, enlargement of existing AVMs, and hemorrhage which may be life-threatening (Ference et al., 1994; Shovlin et al., 1995, 2008; de Gussem et al., 2014).

Relevance to HHT Clinical Trials

Hemodynamic parameters are increasingly used to evaluate treatment efficacy in HHT clinical trials. Reduction in cardiac index, measured by echocardiography, was the primary efficacy criterion in an evaluation of Bevacizumab in 25 patients with severe hepatic AVMs: 6 months treatment reduced the cardiac index from 5.1 L/min/m2 to 4.1 L/min/m2, and pulmonary hypertension regressed in five cases (Dupuis-Girod et al., 2012). In a separate study evaluating liver transplantation for severe hepatic AVMs, the mean cardiac index fell from 5.75 L/min/m2 to 3.4 L/min/m2 (Dupuis-Girod et al., 2010).

Hemorrhage, Iron Deficiency, and Anemia

Patients with HHT are prone to iron deficiency because of chronic and repeated blood losses from nasal and gastrointestinal telangiectasia. HHT telangiectasia have fragile walls, often lined by a single endothelial layer with no smooth muscle cells or pericytes, despite acting as conduits for blood at arterial pressure (Braverman et al., 1990).

Anemia develops because iron is required to synthesize hemoglobin. Iron handling is generally normal in HHT (Finnamore et al., 2013)- if total body iron stores fall, circulating levels of hepcidin also fall, facilitating iron absorption through the gastrointestinal tract, and iron recycling from hepatocytes and senescent erythrocytes (Ganz, 2013). Over time, if iron intake remains insufficient for needs, body stores are exhausted, leading to iron deficiency. The ‘hemorrhage adjusted iron requirement’ helps predict when iron deficiency is likely to occur, if additional iron supplements are not given (Finnamore et al., 2013).

Additional iron can be ingested orally, and/or administered through iron infusions. However, chronic anemia of a severity sufficient to require red cell (blood) transfusions is common in HHT: One survey reported that 243/915 (26.6%) HHT patients had received a blood transfusion due to epistaxis (nosebleeds, Hoag et al., 2010), and another, that 39/220 (17.7%) patients had required blood transfusions on at least 10 separate occasions (Elphick and Shovlin, 2014).

Limiting HHT blood losses reduces the amount of iron required to avoid iron deficiency and anemia. Strategies include classical otorhinolaryngology surgery; limitation of epistaxis triggers such as hypertension (Purkey et al., 2014), allergic rhinitis/sinusitis (Purkey et al., 2014), dietary (Silva et al., 2013; Elphick and Shovlin, 2014), and drug precipitants (Folz et al., 2005; Devlin et al., 2013; Purkey et al., 2014); and newer medical treatments. Recent attention has focused on hormonal manipulations (Yaniv et al., 2009; Albiñana et al., 2010), thalidomide (Lebrin et al., 2010), tranexamic acid (Gaillard et al., 2014: Geisthoff et al., 2014), and intranasal Bevacizumab (Karnezis and Davidson, 2012; Dupuis-Girod et al., 2014; Riss et al., 2014). There are a number of reports and small, uncontrolled case series reporting the benefits of systemic bevacizumab and other agents, though randomized trials are as yet lacking.

Anemia, Iron, and Cardiac Output

Chronic anemia leads to reduced systemic vascular resistance and high cardiac outputs in the general population (Porter and Watson, 1953; Anand et al., 1993; Hébert et al., 2004). Treatment of iron deficiency has beneficial effects in general heart failure (Ponikowski et al., 2014): benefits observed in the absence of anemia are attributed to the major iron requirements of tissues with high-energy demands such as the heart and skeletal muscle (Cohen-Solal et al., 2014).

For patients with HHT and hepatic AVMs, the largest prospective series identified iron deficiency anemia as the most common precipitant of high output cardiac failure (Buscarini et al., 2011). In the hepatic AVM-Bevacizumab trial (Dupuis-Girod et al., 2012), the relevance of reduced epistaxis (from 221 to 43 min/month), and modest hemoglobin increase, is not yet known.

Thromboses in a Hemorrhagic Condition

Despite their frequent hemorrhages, HHT patients are at risk of deep venous thromboses and pulmonary emboli, i.e., venous thromboemboli (VTE; Shovlin et al., 2007; Livesey et al., 2012). A study of 609 consecutive patients with HHT demonstrated an ∼2.5-fold increase in VTE risk with low serum iron (Livesey et al., 2012). The association was evident in “healthy” HHT patients in the community, and appeared to be mediated through elevated coagulation factor VIII (Livesey et al., 2012), which is a well-established risk factor for first and recurrent VTE in the general population (Kyrle et al., 2000; Cosmi et al., 2008; Vormittag et al., 2009; Pabinger et al., 2013; Kovac et al., 2015).

Approximately 50% of HHT patients have pulmonary AVMs and are also at risk of paradoxical embolic strokes because systemic venous blood can bypass the normal pulmonary capillary filter (Shovlin, 2014a; Shovlin et al., 2014). In a study published 15 years ago, 34/67 patients with pulmonary AVMs had evidence of cerebral infarcts on MRI scans (Moussouttas et al., 2000). Myocardial infarcts are also attributed to paradoxical emboli in HHT patients with pulmonary AVMs (Clark et al., 2013). In a series of 497 consecutive patients with CT-proven pulmonary AVMs due to HHT, a low serum iron was a strong risk factor for a clinical ischemic stroke: for the same pulmonary AVMs, the stroke risk would approximately double with serum iron 6 μmol/L compared to mid-normal range (Shovlin et al., 2014). Platelet studies confirmed overlooked data that iron deficiency is associated with exuberant platelet aggregation to 5HT/serotonin (Woods et al., 1977; Shovlin, 2014b; Shovlin et al., 2014).

Pulmonary AVMs and Hypoxemia

Pulmonary AVMs lead to low oxygen levels in the blood (hypoxemia) because they allow a fraction of pulmonary arterial blood to bypass the pulmonary capillary bed and hence gas exchange (Shovlin, 2014a).

However, in the chronic state, individuals with adequate iron supplies maintain their total arterial oxygen content (CaO2) by increasing hemoglobin using an apparently graded erythrocytotic response (Santhirapala et al., 2014a). Similar findings are observed in the general population at altitude, when compensatory responses can be evident within 7 days (Ryan et al., 2014). For pulmonary AVM patients, compensations were shown to be less successful if iron deficiency was present (Santhirapala et al., 2014a). After successful embolization treatment of pulmonary AVMs, hematologic compensatory responses are lost. Patients appeared to reset to the same CaO2, unless there was an interim correction of iron deficiency (Santhirapala et al., 2014a).

Pulmonary AVMs also result in high cardiac outputs, with exact mechanisms differing to systemic AVMs, due to the lower blood oxygenation. At rest and on exercise, increased stroke volumes are utilized (Whyte et al., 1993; Howard et al., 2014; Vorselaars et al., 2014). The heart rate normally increases on standing, but in patients with pulmonary AVMs and a sudden drop in SaO2 on standing, the heart rate increases further, inversely proportional to the fall in SaO2 (Santhirapala et al., 2014b). After correction of hypoxemia by embolization treatments, hemodynamic compensatory responses are lost (Vorselaars et al., 2014).

The loss of both hematologic and hemodynamic compensatory responses following embolization helps explain why exercise capacity, and oxygen consumption are frequently no higher after embolization, despite substantial increases in SaO2 (Howard et al., 2014; Shovlin, 2014a; Yasuda et al., 2015).

HHT-Independent Factors

Hemodynamics

HHT-independent causes of reduced systemic vascular resistance and high cardiac outputs include exercise, pyrexia, other forms of anemia, pregnancy, sepsis, liver cirrhosis, and use of systemic vasodilating agents (Anand and Florea, 2001; Mehta and Dubrey, 2009).

Hemorrhage

‘Hemorrhagic’ iron losses occur in multiple settings including menstruation, blood donation, and surgery. All lead to greater iron requirements for the HHT patient (Finnamore et al., 2013). Concurrent coagulation disorders, drugs (Devlin et al., 2013), and even dietary agents (Silva et al., 2013; Elphick and Shovlin, 2014) are reported to increase hemorrhagic losses in HHT.

Iron Handling

Iron handling is controlled by hepcidin, a liver-synthesized peptide hormone which is normally expressed at lower levels in iron deficiency, facilitating gastrointestinal iron absorption, and iron recycling from macrophages and hepatocytes, through the iron transporter ferroportin (Ganz, 2013). Active bleeding further represses hepcidin expression via erythroferrone (Kautz et al., 2014). However, inflammatory and other chronic disease states often result in inappropriately high hepcidin levels, and failure to absorb oral iron irrespective of doses ingested (Ganz, 2013). In HHT, the hepcidin/ferroportin axis appears to operate normally: generally, hepcidin levels are appropriately low in iron deficiency, displaying similar relationships to ferritin as for healthy controls (Finnamore et al., 2013). However, intercurrent illnesses are predicted to perturb these normal relationships, and aggravate iron deficiency.

Thromboses

A description of the potential causes of pathological venous and arterial thromboses is beyond the scope of this text. Surprisingly, of 379 patients with HHT who received antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy (usually to treat or prevent VTE, ischemic strokes or cardiac conditions), 153 (40.4%) reported no change in their nosebleeds, and 9 (2.4%) reported an improvement (Devlin et al., 2013).

Conversely, tamoxifen, raloxifene, tranexamic acid, thalidomide, and Bevacizumab that are used to treat HHT-related bleeding are also recognized in certain circumstances to expose patients to enhanced risk of thrombosis. To date, thrombotic events have not been reported in the HHT clinical trials, but a history of previous thrombosis is considered a contraindication to their use in HHT.

Conclusion

From a mechanistic perspective, these circulatory contributors to the phenotype in HHT increase the complexity of the disorder. New paradigms are added to current research foci, and new ontology groupings to potential HHT modifier gene lists. Therapeutic targeting of hemorrhage and visceral AVMs in HHT remain major challenges. The states discussed above remind of the potential value of concurrent, simple treatment approaches, particularly preventing or correcting iron deficiency.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Shovlin thanks colleagues (especially Dr. James Jackson), students, and patients for helpful discussions. Work in Dr. Shovlin’s laboratory is supported by donations from HHT families, including the Averil Macdonald and Margaret Straker Memorial Funds.

References

- Albiñana V., Bernabeu-Herrero M. E., Zarrabeitia R., Bernabéu C., Botella L. M. (2010). Estrogen therapy for hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT): effects of raloxifene, on endoglin and ALK1 expression in endothelial cells. Thromb. Haemost. 103 525–534 10.1160/TH09-07-0425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand I. S., Chandrashekhar Y., Ferrari R., Poole-Wilson P. A., Harris P. C. (1993). Pathogenesis of oedema in chronic severe anaemia: studies of body water and sodium, renal function, haemodynamic variables, and plasma hormones. Br. Heart J. 70 357–362 10.1136/hrt.70.4.357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand I. S., Florea V. G. (2001). High output cardiac failure. Curr. Treat. Options Cardiovasc. Med. 3 151–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braverman I. M., Keh A., Jacobson B. S. (1990). Ultrastructure and three-dimensional organization of the telangiectases of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. J. Invest. Dermatol. 95 422–427 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12555569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buscarini E., Leandro G., Conte D., Danesino C., Daina E., Manfredi G., et al. (2011). Natural history and outcome of hepatic vascular malformations in a large cohort of patients with hereditary hemorrhagic teleangiectasia. Dig. Dis. Sci. 56 2166–2178 10.1007/s10620-011-1585-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark K., Pyeritz R. E., Trerotola S. O. (2013). Angina pectoris or myocardial infarctions, pulmonary arteriovenous malformations, hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia, and paradoxical emboli. Am. J. Cardiol. 112 731–734 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.04.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Solal A., Leclercq C., Mebazaa A., De Groote P., Damy T., Isnard R., et al. (2014). Diagnosis and treatment of iron deficiency in patients with heart failure: expert position paper from French cardiologists. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 107 563–571 10.1016/j.acvd.2014.07.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosmi B., Legnani C., Cini M., Favaretto E., Palareti G. (2008). D-dimer and factor VIII are independent risk factors for recurrence after anticoagulation withdrawal for a first idiopathic deep vein thrombosis. Thromb. Res. 122 610–617 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Gussem E. M., Lausman A. Y., Beder A. J., Edwards C. P., Blanker M. H., Terbrugge K. G., et al. (2014). Outcomes of pregnancy in women with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Obstet. Gynecol. 123 514–520 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin H. L., Hosman A. E., Shovlin C. L. (2013). Antiplatelets and anticoagulants in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. New Engl. J. Med. 368 876–878 10.1056/NEJMc1213554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis-Girod S., Ambrun A., Decullier E., Samson G., Roux A., Fargeton A. E., et al. (2014). ELLIPSE Study: a Phase 1 study evaluating the tolerance of bevacizumab nasal spray in the treatment of epistaxis in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. MAbs 6 794–799 10.4161/mabs.28025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis-Girod S., Chesnais A. L., Ginon I., Dumortier J., Saurin J. C., Finet G., et al. (2010). Long-term outcome of patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia and severe hepatic involvement after orthotopic liver transplantation: a single-center study. Liver Transpl. 16 340–347 10.1002/lt.21990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis-Girod S., Ginon I., Saurin J. C., Marion D., Guillot E., Decullier E., et al. (2012). Bevacizumab in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia and severe hepatic vascular malformations and high cardiac output. JAMA 307 948–955 10.1001/jama.2012.250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elphick A., Shovlin C. L. (2014). Relationships between epistaxis, migraines, and triggers in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Laryngoscope 124 1521–1528 10.1002/lary.24526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ference B. A., Shannon T. M., White R. I., Zawin M., Burdge C. M. (1994). Life threatening pulmonary hemorrhage with pulmonary arteriovenous malformations and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Chest 106 1387–1392 10.1378/chest.106.5.1387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnamore H., Le Couteur J., Hickson M., Busbridge M., Whelan K., Shovlin C. L. (2013). Hemorrhage-adjusted iron requirements, hematinics and hepcidin define hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia as a model of hemorrhagic iron deficiency. PLoS ONE 8:e76516 10.1371/journal.pone.0076516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folz B. J., Tennie J., Lippert B. M., Werner J. A. (2005). Natural history and control of epistaxis in a group of German patients with Rendu-Osler-Weber disease. Rhinology 43 40–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard S., Dupuis-Girod S., Boutitie F., Rivière S., Morinière S., Hatron P. Y., et al. (2014). Tranexamic acid for epistaxis in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia patients: a European cross-over controlled trial in a rare disease. J. Thromb. Haemost. 12 1494–1502 10.1111/jth.12654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz T. (2013). Systemic iron homeostasis. Physiol. Rev. 93 1721–1741 10.1152/physrev.00008.2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisthoff U. W., Seyfert U. T., Kübler M., Bieg B., Plinkert P. K., König J. (2014). Treatment of epistaxis in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia with tranexamic acid – a double-blind placebo-controlled cross-over phase IIIB study. Thromb. Res. 134 565–571 10.1016/j.thromres.2014.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hébert P. C., Van der Linden P., Biro G., Hu L. Q. (2004). Physiologic aspects of anaemia. Crit. Care Clin. 20 187–212 10.1016/j.ccc.2004.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoag J. B., Terry P., Mitchell S., Reh D., Merlo C. A. (2010). An epistaxis severity score for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Laryngoscope 120 838–843 10.1002/lary.20818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard L. S., Santhirapala V., Murphy K., Mukherjee B., Busbridge M., Tighe H. C., et al. (2014). Cardiopulmonary exercise testing demonstrates maintenance of exercise capacity in hypoxemic patients with pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. Chest 146 709–718 10.1378/chest.13-2988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnezis T. T., Davidson T. M. (2012). Treatment of hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia with submucosal and topical bevacizumab therapy. Laryngoscope 122 495–497 10.1002/lary.22501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kautz L., Jung G., Valore E. V., Rivella S., Nemeth E., Ganz T. (2014). Identification of erythroferrone as an erythroid regulator of iron metabolism. Nat. Genet. 46 678–684 10.1038/ng.2996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovac M., Kovac Z., Tomasevic Z., Vucicevic S., Djordjevic V., Pruner I., et al. (2015). Factor V Leiden mutation and high FVIII are associated with an increased risk of VTE in women with breast cancer during adjuvant tamoxifen – Results from a prospective, single center, case control study. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 26 63–67 10.1016/j.ejim.2014.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyrle P. A., Minar E., Hirsch M., Bialonczyk C., Stain M., Schneider B., et al. (2000). High plasma levels of factor VIII and the risk of recurrent venous thromboembolism. New Engl. J. Med. 343 457–462 10.1056/NEJM200008173430702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebrin F., Srun S., Raymond K., Martin S., van den Brink S., Freitas C., et al. (2010). Thalidomide stimulates vessel maturation and reduces epistaxis in individuals with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Nat. Med. 16 420–428 10.1038/nm.2131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livesey J. A., Manning R. A., Meek J. H., Jackson J. E., Kulinskaya E., Laffan M. A., et al. (2012). Low serum iron levels are associated with elevated plasma levels of coagulation factor VIII and pulmonary emboli/deep venous thromboses in replicate cohorts of patients with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Thorax 67 328–333 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-201076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald J., Bayrak-Toydemir P., Pyeritz R. E. (2011). Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: an overview of diagnosis, management, and pathogenesis. Genet. Med. 13 607–616 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3182136d32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta P. A., Dubrey S. W. (2009). High output heart failure. QJM 102 235–241 10.1093/qjmed/hcn147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussouttas M., Fayad P., Rosenblatt M., Hashimoto M., Pollak J., Henderson K., et al. (2000). Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: cerebral ischemia and neurologic manifestations. Neurology 55 959–964 10.1212/WNL.55.7.959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens C. D. (2010). Adaptive changes in autogenous vein grafts for arterial reconstruction: clinical implications. J. Vasc. Surg. 51 736–746 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.07.102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pabinger I., Thaler J., Ay C. (2013). Biomarkers for prediction of venous thromboembolism in cancer. Blood 122 2011–2018 10.1182/blood-2013-04-460147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponikowski P., van Veldhuisen D. J., Comin-Colet J., Ertl G., Komajda M., Mareev V., et al. (2014). Beneficial effects of long-term intravenous iron therapy with ferric carboxymaltose in patients with symptomatic heart failure and iron deficiency. Eur. Heart J. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu385 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter W. B., Watson J. G. (1953). The heart in anaemia. Circulation 8 111–116 10.1161/01.CIR.8.1.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purkey M. R., Seeskin Z., Chandra R. (2014). Seasonal variation and predictors of epistaxis. Laryngoscope 124 2028–2033 10.1002/lary.24679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riss D., Burian M., Wolf A., Kranebitter V., Kaider A., Arnoldner C. (2014). Intranasal submucosal bevacizumab for epistaxis in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Head Neck [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan B. J., Wachsmuth N. B., Schmidt W. F., Byrnes W. C., Julian C. G., Lovering A. T., et al. (2014). AltitudeOmics: rapid hemoglobin mass alterations with early acclimatization to and de-acclimatization from 5260 m in healthy humans. PLoS ONE 9:e108788 10.1371/journal.pone.0108788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santhirapala V., Williams L. C., Tighe H. C., Jackson J. E., Shovlin C. L. (2014a). Arterial oxygen content is precisely maintained by graded erythrocytotic responses in settings of high/normal serum iron levels, and predicts exercise capacity: an observational study of hypoxaemic patients with pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. PLoS ONE 9:e90777 10.1371/journal.pone.0090777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santhirapala V., Chamali B., McKernan H., Tighe H. C., Williams L. C., Springett J. T., et al. (2014b). Orthodeoxia and postural orthostatic tachycardia in patients with pulmonary arteriovenous malformations: a prospective 8-year series. Thorax 69 1046–1047 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-205289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shovlin C. L. (2010). Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Blood Rev. 24 203–219 10.1016/j.blre.2010.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shovlin C. L. (2014a). Pulmonary arteriovenous malformations. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 190 1217–1228 10.1164/rccm.201407-1254CI [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shovlin C. L. (2014b). Iron deficiency, ischaemic strokes, and right-to-left shunts: from pulmonary arteriovenous malformations to patent foramen ovale? Intract. Rare Dis. Res. 3 60–64 10.5582/irdr.2014.01008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shovlin C. L., Chamali B., Santhirapala V., Livesey J. A., Angus G., Manning R., et al. (2014). Ischaemic strokes in patients with pulmonary arteriovenous malformations and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: associations with iron deficiency and platelets. PLoS ONE 9:e88812 10.1371/journal.pone.0088812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shovlin C. L., Sodhi V., McCarthy A., Lasjaunias P., Jackson J. E., Sheppard M. N. (2008). Estimates of maternal risks of pregnancy for women with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome): suggested approach for obstetric services. BJOG 115 1108–1115 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01786.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shovlin C. L., Sulaiman N. L., Govani F. S., Jackson J. E., Begbie M. E. (2007). Elevated factor VIII in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT): association with venous thromboembolism. Thromb. Haemost. 98 1031–1039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shovlin C. L., Winstock A. R., Peters A. M., Jackson J. E., Hughes J. M. B. (1995). Medical complications of pregnancy in hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia. Quart. J. Med. 88 879–887. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva B. M., Hosman A. E., Devlin H. L., Shovlin C. L. (2013). Lifestyle and dietary influences on nosebleed severity in hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Laryngoscope 123 1092–1099 10.1002/lary.23893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vormittag R., Simanek R., Ay C., Dunkler D., Quehenberger P., Marosi C., et al. (2009). High factor VIII levels independently predict venous thromboembolism in cancer patients: the cancer and thrombosis study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 29 2176–2181 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.190827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorselaars V. M., Velthuis S., Mager J. J., Snijder R. J., Bos W. J., Vos J. A., et al. (2014). Direct haemodynamic effects of pulmonary arteriovenous malformation embolisation. Neth. Heart J. 22 328–333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte M. K., Hughes J. M., Jackson J. E., Peters A. M., Hempleman S. C., Moore D. P., et al. (1993). Cardiopulmonary response to exercise in patients with intrapulmonary vascular shunts. J. Appl. Physiol. 75 321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods H. F., Youdim M. B. H., Boullin D., Callender S. (1977). “Monoamine metabolism and platelet function in iron-deficiency anaemia: iron metabolism,” in Proceedings of the CIBA Foundation Symposium 51 (Amsterdam: Elsevier; ), 227–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaniv E., Preis M., Hadar T., Shvero J., Haddad M. (2009). Antiestrogen therapy for hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Laryngoscope 119 284–288 10.1002/lary.20065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda W., Jackson J. E., Layton D. M., Shovlin C. L. (2015). Hypoxaemia, sport and polycythaemia: a case from Imperial College London. Thorax 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]