Abstract

Background

Previous studies suggest that minorities cluster in low-quality hospitals despite living close to better performing hospitals. This may contribute to persistent disparities in cancer outcomes.

Objective

To examine how travel distance, insurance status, and neighborhood socioeconomic factors influenced minority under-utilization of high-volume hospitals for colorectal cancer.

Settings

All hospitals in California from 1996–2006

Patients

Colorectal patients from the California Cancer Registry undergoing resection between 1996–2006.

Main Outcome Measures

Multivariable logistic regression models predicting high-volume hospital use were adjusted for age, gender, race, stage, comorbidities, insurance status, and neighborhood socioeconomic factors.

Results

95,363 patients from 417 hospitals were included in the study. High-volume hospitals were independently associated with an 8% decrease in the hazard of death compared to other settings. A lower proportion of minorities used high-volume hospitals despite a higher proportion living nearby. Although insurance status and socioeconomic factors were independently associated with high-volume hospital use, only socioeconomic factors attenuated differences in high-volume hospital utilization of Black and Hispanic patients compared with whites.

Limitations

Use of cross-sectional data, racial and ethnic misclassification

Conclusions

Minority patients do not use high-volume hospitals despite improved outcomes and geographic access. Low socioeconomic status predicts low utilization of high-volume settings in select minority groups. Our results provide a roadmap for developing interventions to increase the use of and access to higher quality care and outcomes. Increasing minority utilization of high-volume hospitals may require community outreach programs and changes in physician referral practices.

Keywords: disparities, minority health, colorectal cancer, high-volume hospitals, socioeconomic factors, insurance

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the fourth most commonly diagnosed malignancy in all US adults and the second most common cause of cancer death.1 Although overall CRC incidence and mortality have declined in the past decades, racial and ethnic disparities in CRC outcomes have persisted.1–6 Observed racial differences in survival have been attributed to diagnosis at advance stages of disease and differences in the receipt of surgical therapy.7–10 In addition, emerging explanations for cancer disparities have pointed to a correlation between the characteristics of the hospitals where minority patients receive treatment and cancer mortality.11,12 In previous research, we found that certain minority groups under-utilize National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers13 despite evidence showing improved outcomes associated with care in these settings.14,15

High-volume hospitals (HVH) have also been shown to have a positive association with outcomes in colorectal cancer.16–21 For example, Harmon et al. reported that increasing hospital volume was associated with decreased length of stay, lower hospital charges, and lower rates of in-hospital mortality.16 Schrag et al. found that increasing hospital volume of colorectal operations was associated with decreased 30-day and 2-year mortality as well as reduced ostomy rates (even after taking into account individual surgeon volume).19 In 2007, Billingsley et al. showed a protective association between the use of high volume and very high volume hospitals and 30-day colon cancer mortality.20 The investigators discovered that the association between volume and colon cancer outcomes was related to differences in clinical resources available in these settings. Most recently, Etzioni et al. found that patients treated in centers that have higher volume experience better overall survival, with differences persisting despite adjustment for individual surgeon volume.21

Nonetheless, recent studies have shown that minorities tend to receive treatment at low-volume and low quality hospitals,22–25 and this is also true for colorectal cancer.24,26 One potential barrier to high quality care may be geographic availability or travel distance. Patients often receive their care locally even when associated with worse outcomes.27 In previous investigations, there appeared to be a negative effect of increasing travel time and distance on utilization of NCI-designated cancer centers.13,28 Still, others have shown that minorities with Medicare use low-quality settings, despite living closer to high-quality hospitals.25 These findings suggest something more at work than travel distance and may indicate differences in provider referral patterns. Minorities with cancer are less likely to be referred to high-volume centers29 and specialists.30 They also live in counties served by fewer specialists with diminished access to surgical facilities and resources31,32 and tend to receive their care from a small pool of lower quality physicians.33

In this study, we sought to understand how geographic accessibility, insurance status, and socioeconomic status (SES) factors influence minority under-utilization of HVH in an all-payer, all age, racially and ethnically diverse dataset. We hypothesize that travel distance and neighborhood SES factors will predict minority use of high volume settings. A more ecological understanding of factors that determine where minorities receive care will guide future interventions to improve minority access to high quality settings potentially addressing disparities in cancer care and outcomes.

METHODS

This study uses the same sources of data, study population, and geographic information systems (GIS) analysis previously described in our study examining minority utilization of National Cancer Institute-designated Cancer Centers.13 Briefly, our data was drawn from a large-state, all payer administrative database comprised of a linkage between the California Cancer Registry (CCR) and the California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development Patient Discharge Database (OSHPD-PDD). We identified all patients with colon and rectal cancer surgically treated between 1996 and 2006. We excluded patients enrolled in California’s largest health maintenance organization (HMO) as these patients are limited in where they can receive treatment. Neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics were based on census block group data on the percent of residents living below 200% of the federal poverty level (% poverty), percent unemployed (% unemployment), and the percent of block group level residents with college education (% college). Geo-coding and calculation of the distance between patients, nearby hospitals, and the hospital where they received treatment was performed using GIS software (ArcGIS 10; Ersi Inc., Redlands, California). A hospital within a radius less than or equal to the calculated median travel distance for the state was considered “nearby.”

For the analysis specific to this study, we defined high volume hospitals as those in the highest quintile of colon and rectal resections by annual volume of all hospitals in California. Statistical analysis was done using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina). Chi-square analysis was used to compare the proportions of each racial and ethnic group living near a high volume setting. A Cox regression model predicting the risk of death after surgery at HVH versus non-HVH was adjusted for age, gender, race, stage, insurance status, and neighborhood socioeconomic factors. Multivariable logistic regression models predicting HVH use were adjusted for age, gender, stage, comorbidities, insurance status, and neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics. The baseline model was limited to demographic and clinical factors. Subsequent models assessed the independent association of each additional set of factors. Model 2 was further adjusted for insurance type. Model 3 assessed the impact of socioeconomic factors. All comparisons were two-tailed and p-values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 79,231 diagnosed with colorectal cancer (CRC) and treated in 417 hospitals were identified. There were 44,691 (56%) patients treated in 83 HVH settings. The median distance for treatment was 4.7 and 5.5 miles for colon and rectal cancer, respectively. This calculated median travel distance was used to define “nearby” hospitals. Table 1 shows the socio-demographic and characteristics of patients included in the analysis. HVH settings were independently associated with an 8% decrease in the hazard of death (hazard ratio 0.92; 95% CI 0.90–0.94) compared to non-HVH settings after adjusting for patient characteristics, insurance status, and neighborhood socioeconomic factors.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics (Colorectal cancer, California 1996–2006)

| Characteristics | Cohort total | HVH N (%) |

Non-HVH N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 79231 | 44691 | 34540 |

| Age (years) | |||

| 0–44 | 3310 (4.2) | 1851 (4.1) | 1459 (4.2) |

| 45–54 | 7745 (9.8) | 4463 (10) | 3282 (9.5) |

| 55–64 | 12929 (16.3) | 7196 (16.1) | 5733 (16.6) |

| 65–74 | 21488 (27.1) | 12091 (27.1) | 9397 (27.2) |

| 75–84 | 24024 (30.3) | 13602 (30.4) | 10422 (30.2) |

| 85-high | 9735 (12.3) | 5488 (12.3) | 4247 (12.3) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 39100 (49.3) | 22166 (49.6) | 16934 (49) |

| Female | 40131 (50.7) | 22525 (50.4) | 17606 (51) |

| Race | |||

| White | 57764 (72.9) | 34031 (76.1) | 23733 (68.7) |

| Black | 4260 (5.4) | 2042 (4.6) | 2218 (6.4) |

| Hispanic | 9381 (11.8) | 4371 (9.8) | 5010 (14.5) |

| API | 7826 (9.9) | 4247 (9.5) | 3579 (10.4) |

| Cancer Type | |||

| Colon | 62510 (78.9) | 34928 (78.2) | 27582 (79.9) |

| Rectum | 16721 (21.1) | 9763 (21.8) | 6958 (20.1) |

| Stage | |||

| Stage I | 16563 (20.9) | 9681 (22.2) | 6882 (20.3) |

| Stage II | 25057 (31.6) | 13939 (31.9) | 11118 (32.9) |

| Stage III | 21884 (27.6) | 12401 (28.4) | 9483 (28.0) |

| Stage IV | 11235 (14.2) | 6207 (14.2) | 5028 (14.9) |

| Stage unknown | 2786 (3.5) | 1463 (3.3) | 1323 (3.9) |

| Insurance Status | |||

| Private | 28586 (36.1) | 18065 (44.2) | 10521 (33.6) |

| Medicaid | 4016 (5.1) | 1526 (3.7) | 2490 (8.0) |

| Medicare | 38401 (48.5) | 20880 (51.1) | 17521 (56.0) |

| Uninsured | 1190 (1.5) | 425 (1.0) | 765 (2.4) |

|

Neighborhood Characteristics (median, IQR) |

|||

| % unemployment | 96.8 (94.8, 98.2) | 97.0 (95.2, 98.4) | 96.4 (94.4-97.9) |

| % college education | 33.0 (19.4, 50.1) | 37.6 (22.5, 54.2) | 28.1 (16.7, 43.0) |

| % poverty | 76.9 (60.2, 87.7) | 79.3 (63.4, 89.2) | 73.2 (56.5, 85.1) |

Abbreviations: API=Asian/Pacific Islander; HVH=high volume hospital; % unemployment=proportion of those in census block who are unemployed; % college education=proportion of the census block with a college education. % poverty=proportion of those in census block living below 200% Federal Poverty Level (FPL).

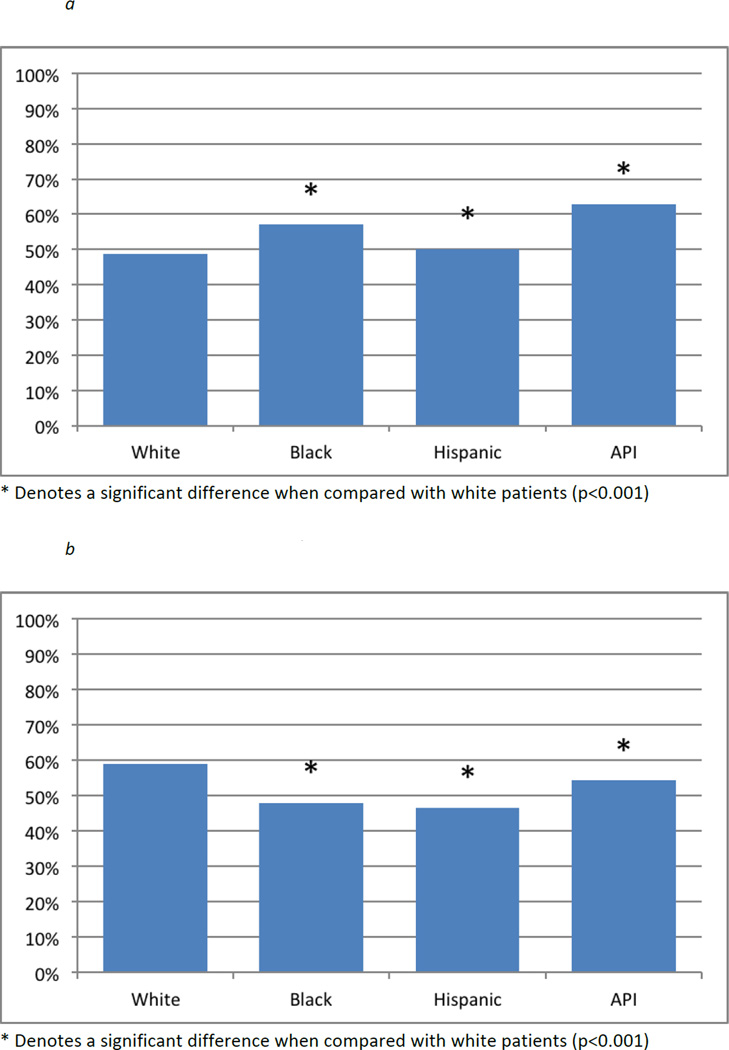

Figure 1a shows the proportions of each racial/ethnic group living within the median travel distance of an HVH, while Figure 1b shows the proportion in each racial/ethnic group who took advantage of living nearby and sought care there. All racial and ethnic minority groups lived near HVH in significantly higher proportions than White patients (all p<0.001). Figure 1B shows that significantly lower proportions of every minority group used HVH compared with White patients (all p<0.001).

Figure 1.

a – Proportion of each racial/ethnic group living near a high-volume hospital, by race (Colorectal cancer, California 1996–2006)

b – Proportion of each racial/ethnic group using a high-volume hospital, by race (Colorectal cancer, California 1996–2006)

A logistic regression model predicting use of HVH by demographic and clinical characteristics is shown in Table 2. In this baseline model, estimates are adjusted for race, gender, age, and stage of disease. There was a negative association between each minority group and HVH use. There was a 36% lower odds [OR 0.64 (95%CI 0.60–0.68)] associated with Black race. Hispanic ethnicity was associated with 40% lower odds [OR 0.60 (95% CI 0.58–0.63)]; and API race/ethnicities were associated with 18% lower odds [OR 0.82 (95% CI 0.78–0.86)] of HVH use in comparison to White patients. Patients with Stage II, III, and IV disease were all less likely to use HVH compared with those with Stage I disease [Stage II OR 0.89 (95%CI 0.86–0.93); Stage III OR 0.94 (95%CI 0.91–0.98); Stage IV OR 0.89 (95%CI 0.85–0.93)].

Table 2.

Logistic regression model predicting the odds of using high volume hospitals (Colorectal cancer, California 1996–2006)

| Model 1: Baseline | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | OR | 95% CI | P value |

| Race | |||

| White | 1 (ref) | ||

| Black | 0.64 | 0.60–0.68 | <0.001* |

| Hispanic | 0.60 | 0.58–0.63 | <0.001* |

| API | 0.82 | 0.78–0.86 | <0.001* |

| Age | |||

| 0–44 | 1 (ref) | ||

| 45–54 | 1.02 | 0.94–1.11 | 0.59 |

| 55–64 | 0.93 | 0.86–1.00 | 0.059 |

| 65–74 | 0.94 | 0.87–1.01 | 0.089 |

| 75–84 | 0.92 | 0.86–0.99 | 0.034* |

| 85-high | 0.90 | 0.83–0.980 | 0.012* |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1 (ref) | ||

| Female | 0.98 | 0.95–1.00 | 0.148 |

| Stage | |||

| I | 1 (ref) | ||

| II | 0.89 | 0.86–0.93 | <0.001* |

| III | 0.94 | 0.91–0.98 | 0.003* |

| IV | 0.89 | 0.85–0.93 | <0.001* |

| Missing data | 0.80 | 0.74–0.86 | <0.001* |

Abbreviations: *=p<0.05, API=Asian Pacific Islander; OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval; ref=reference

In Table 3, we assessed the impact of insurance status (Model 2) and socioeconomic status factors (Model 3) on HVH use. Compared with private insurance, we found an independent and negative association between all insurance types and HVH utilization. Despite these strong associations, the negative correlation between minority race and HVH utilization persisted [Black OR 0.68 (95%CI 0.64–0.73); Hispanic OR 0.64 (95%CI 0.61–0.67); API OR 0.88 (95%CI 0.84–0.92)]. When neighborhood SES factors were added to the model, the difference in odds of utilization of HVH by Black and Hispanic patients decreased 15% and 17%, respectively [Black OR 0.83 (95% CI 0.78–0.89); Hispanic OR 0.81 (95%CI 0.77–0.85)]. Decreasing levels of unemployment and increasing levels of college education were each independently associated with increasing odds of HVH use. In the full model, decreasing levels of poverty were associated with decreased utilization of HVH.

Table 3.

Logistic regression models estimating the odds of HVH use for racial/ethnic minority groups, adjusted for insurance status and socioeconomic status factors (Colorectal Cancer, California 1996–2006)

| Model 2: Baseline + Insurance Status |

Model 3: Baseline + Insurance + SES factors |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Characteristics | OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | ||||

| Black | 0.68 | 0.64–0.73 | <0.001* | 0.83 | 0.78–0.89 | <0.001* |

| Hispanic | 0.64 | 0.61–0.67 | <0.001* | 0.81 | 0.77–0.85 | <0.001* |

| API | 0.88 | 0.84–0.92 | <0.001* | 0.86 | 0.82–0.90 | <0.001* |

| Insurance | ||||||

| Private | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | ||||

| Medicaid | 0.39 | 0.37–0.42 | <0.001* | 0.43 | 0.40–0.46 | <0.001* |

| Medicare | 0.70 | 0.67–0.72 | <0.001* | 0.68 | 0.66–0.71 | <0.001* |

| No insurance | 0.36 | 0.31–0.40 | <0.001* | 0.37 | 0.33–0.42 | <0.001* |

| Missing data | 0.67 | 0.64–0.71 | <0.001* | 0.68 | 0.65–0.72 | <0.001* |

| Neighborhood SES (continuous) | ||||||

| % unemployment (decreasing) | 1.02 | 1.02–1.02 | <0.001* | |||

| % college education (increasing) | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | <0.001* | |||

| % poverty (decreasing) | 0.99 | 0.99–0.99 | <0.001* | |||

Model 2 is adjusted for age, gender, stage of disease, and insurance status; Model 3 includes all previously listed factors + neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics.

Abbreviations: *=p<0.05, API=Asian Pacific Islander; OR=odds ratio; CI= confidence interval; ref=reference; SES=socioeconomic status; % unemployment=proportion of those in census block who are unemployed; % college education=proportion of the census block with a college education. % poverty=proportion of those in census block living below 200% Federal Poverty Level (FPL).

DISCUSSION

The current study investigated the association between race, geographic proximity, insurance status, and neighborhood SES with minority use of HVH for the treatment of colorectal cancers in California. We found that HVH settings were independently associated with an 8% decrease in the hazard of death compared to non-HVH settings. Our results show that most patients live in relatively close proximity to hospitals where CRC treatment is obtained (≤5.5 miles). While the proportion of minorities living within this travel distance from a HVH is the same or greater when compared with White patients, fewer minorities were served in these settings. In regression models, there was a negative association between minority race/ethnicity and HVH use. This negative association persisted despite adjustment for insurance status. Select SES characteristics – which indicate higher levels of social status (lower unemployment and higher levels of college education) – predicted increased HVH utilization. The addition of SES factors to our regression models were associated with a reduction in the disparity between Black and Hispanic patient use of HVH compared with their White counterparts. There was no significant effect of SES factors on utilization by API patients.

In contrast to other studies22,28, this study did not find that geographic proximity or insurance explained low minority utilization of HVH. Despite the fact that a higher proportion of racial/ethnic minorities reside within 5 miles of an HVH setting, lower proportions of these patients used it. We also found that all insurance types were negatively associated with use of HVH compared with private coverage. Nonetheless, adjustment for insurance status in our models did not change the negative association between minority race/ethnicity and HVH use.

Our study demonstrated an association between improved colorectal outcomes and the use of HVH settings, consistent with other studies16–21. Our findings are also consistent with recent work by Dimick et al., who also found that Black patients were less likely to use high quality hospitals despite the positive association between Black race and living nearby.25 The investigators also found that neighborhood-level characteristics (residential segregation) predicted lower use of high quality hospitals. Similarly, our previous work has demonstrated that while minorities are more likely to live near NCI cancer centers, Blacks and Hispanics are less likely to be treated there.13 We found that neighborhood college education was the strongest driver of racially discrepant selection into a high quality hospital setting. We found a similarly strong influence of neighborhood education on hospital selection in the current study. In fact, accounting for this factor attenuated the difference between Black and Hispanic patients and their White counterparts.

Our study is novel because we have identified a potentially actionable characteristic to identify communities at risk for bypassing a nearby high quality setting in order to seek care in a low quality setting – settings where minorities have been shown to cluster for cancer care.12,34,35 The results of our study suggest that neighborhood level education influences hospital selection by minorities. While the ongoing implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act emphasized insurance expansion, our findings suggest that insurance alone may not be enough to positively impact access to high quality cancer care; socially based neighborhood norms may more heavily influence choice of location of care. Increasing minority utilization of HVH may thus require community engagement efforts and attention by referring providers to the balance between patient preference and referral to settings associated with improved survival.

While no data exists on interventions to reduce disparities in treatment options for CRC, a systematic review found that the most effective interventions to improve the likelihood of CRC screening involved patient education through direct contact (e.g., phone, in-person), patient navigator services, and provider-directed efforts (particularly training for providers working with patients of low health literacy).36 Similar efforts may be needed to educate low SES patients about the potential for differences in cancer outcomes based on location of care. Similarly, interventions to educate minority-serving providers about the importance of high-quality cancer care may help them make better referral and treatment recommendations. A systematic review of the decision making process for minorities with cancer found that providers and provider-patient interactions strongly influence a patients’ decision to pursue treatment.37 Patients treated by providers who failed to advocate strongly for certain treatment modalities or who did not engage their patients in culturally sensitive decision-making are more likely to delay or even choose non-optimal treatment strategies. Provider-level interventions will also need to address previously identified unconscious racial biases which lead to differential treatment and referral recommendations.38,39

LIMITATIONS

An important limitation to consider in our study is the use of cross-sectional registry data. We cannot conclude any causal link between patient characteristics such as race and the location of CRC care. Nonetheless, the strong associations we have uncovered between neighborhood SES factors and HVH use are of great importance. The results of our study clearly identify populations that may benefit from interventions to improve access to high quality care. Another limitation of registry data is that the racial and ethnic classification in the registry can be discordant with patient self-reports.40–43 A previous analysis of CCR data found that misclassification in the registry data likely results in an underestimate of Hispanic cancer cases.44 Given this misclassification, we may erroneously estimate the use of HVH by Hispanic patients. Nonetheless, our findings still provide robust guidance about communities in need of improved access to high quality care regardless of race and ethnicity. We agree with Aspinall and Jacobsen when they argue that disparities “can routinely and successfully be challenged only if organisations are able to demonstrate this in the analysis of their ethnically coded datasets.”45 The magnitude of disparities seen in this study suggests that disparities in HVH utilization by minorities are real and present, even with misclassification. Finally, the study is somewhat limited due to the solitary focus on CRC. We chose CRC because it is a high incident cancer46, affects men and women nearly equally, there are persistent disparities, and the disease is treated in a wide variety of settings, both high and low volume. It is possible that minority patients may seek care for more complex malignancies in HVH settings in equal rates to White patients. In order to confirm the findings in the current investigation, the study should be repeated in other types of cancers.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite the limitations, we found that minority patients do not use HVH settings despite geographic access. Since these settings have been strongly associated with higher quality CRC care and improved survival, efforts to increase access in select populations may positively impact long-standing disparities. Our study identified low SES as a negative predictor of HVH utilization. In doing so, we have provided a roadmap for developing targeted interventions to increase the use of and access to higher quality care and outcomes for racial/ethnic minorities. Future studies should evaluate use of HVH settings in other cancers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Patricia Carbajales for her help with the GIS geocoding and spatial analysis.

Dr. Rhoads and Dr. Huang were supported by the NIH National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Loan Repayment Program. Dr. Rhoads’ work on this project was also supported by funds from the Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Award, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, New Jersey and the National Cancer Institute (1R21CA161786-01A).

Footnotes

All authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

This manuscript was presented at the Surgical Forum of the American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress in San Francisco, California (October 26–30, 2014).

Study conception and design: Huang, Ngo, Rhoads

Acquisition of data: Huang, Ma, Ngo, Rhoads

Analysis and interpretation of data: Huang, Ma, Rhoads

Drafting of manuscript: Huang, Tran, Rhoads

Critical revision: Huang, Tran, Rhoads

REFERENCES

- 1.Irby K, Anderson WF, Henson DE, Devesa SS. Emerging and widening colorectal carcinoma disparities between Blacks and Whites in the United States (1975–2002) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:792–797. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gross CP, Smith BD, Wolf E, Andersen M. Racial disparities in cancer therapy. Cancer. 2008;112:900–908. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polite BN. Colorectal Cancer Model of Health Disparities: Understanding Mortality Differences in Minority Populations. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2179–2187. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rim SH, Seeff L, Ahmed F, King JB, Coughlin SS. Colorectal cancer incidence in the United States, 1999–2004. Cancer. 2009;115:1967–1976. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robbins AS, Siegel RL, Jemal A. Racial disparities in stage-specific colorectal cancer mortality rates from 1985 to 2008. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:401–405. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.5527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soneji S, Iyer SS, Armstrong K, Asch DA. Racial disparities in stage-specific colorectal cancer mortality: 1960–2005. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1912–1916. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chien C, Morimoto LM, Tom J, Li CI. Differences in colorectal carcinoma stage and survival by race and ethnicity. Cancer. 2005;104:629–639. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doubeni CA, Field TS, Buist DSM, et al. Racial differences in tumor stage and survival for colorectal cancer in an insured population. Cancer. 2007;109:612–620. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Govindarajan R, Shah RV, Erkman LG, Hutchins LF. Racial differences in the outcome of patients with colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 2003;97:493–498. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayberry RM, Coates RJ, Hill HA, et al. Determinants of black/white differences in colon cancer survival. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87:1686–1693. doi: 10.1093/jnci/87.22.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lucas FL, Stukel TA, Morris AM, Siewers AE, Birkmeyer JD. Race and surgical mortality in the United States. Ann Surg. 2006;243:281–286. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000197560.92456.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rhoads KF, Ackerson LK, Jha AK, Dudley RA. Quality of colon cancer outcomes in hospitals with a high percentage of Medicaid patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207:197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang LC, Ma Y, Ngo JV, Rhoads KF. What factors influence minority use of National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers? Cancer. 2013;120:399–407. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paulson EC, Mitra N, Sonnad S, et al. National Cancer Institute Designation predicts improved outcomes in colorectal cancer surgery. Ann Surg. 2008;126:318–329. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318187a757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Onega T, Duell EJ, Shi X, Demidenko E, Gottlieb D, Goodman DC. Influence of NCI Cancer Center Attendance on mortality in lung, breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer Patients. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66:542–560. doi: 10.1177/1077558709335536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harmon JW, Tang DG, Gordon TA, et al. Hospital volume can serve as a surrogate for surgeon volume for achieving excellent outcomes in colorectal resection. Ann Surg. 1999;230:404–411. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birkmeyer JD, Siewers AE, Finlayson EVA, et al. Hospital volume and surgical mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1128–1137. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa012337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birkmeyer JD, Sun Y, Wong SL, Stukel TA. Hospital volume and late survival after cancer surgery. Ann Surg. 2007;245:777–783. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000252402.33814.dd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schrag D, Panageas KS, Riedel E, et al. Surgeon volume compared to hospital volume as a predictor of outcome following primary colon cancer resection. J Surg Oncol. 2003;83:68–78. doi: 10.1002/jso.10244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Billingsley KG, Morris AM, Dominitz JA, et al. Surgeon and hospital characteristics as predictors of major adverse outcomes following colon cancer surgery: understanding the volume-outcome relationship. Arch Surg. 2007;142:23–31. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.142.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Etzioni DA, Young-Fadok TM, Cima RR, et al. Patient survival after surgical treatment of rectal cancer: Impact of surgeon and hospital characteristics. Cancer. 2014;120:2472–2481. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu JH, Zingmond DS, Mcgory ML, et al. Disparities in the utilization of high-volume Hospitals for complex surgery. JAMA. 2006;296:1973–1980. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.16.1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riall TS, Eschbach KA, Townsend CM, Nealon WH, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Trends and disparities in regionalization of pancreatic resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1242–1251. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0245-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epstein AJ, Gray BH, Schlesinger M. Racial and ethnic differences in the use of high-volume hospitals and surgeons. Arch Surg. 2010;145:179–186. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dimick J, Ruhter J, Sarrazin MV, Birkmeyer JD. Black patients more likely than whites to undergo surgery at low-quality hospitals in segregated regions. Health Aff. 2013;32:1046–1053. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang W, Ayanian JZ, Zaslavsky AM. Patient characteristics and hospital quality for colorectal cancer surgery. Int J Qual Health Care. 2006;19:11–20. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzl047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finlayson SR, Birkmeyer JD, Tosteson AN, Nease RF. Patient preferences for location of care: implications for regionalization. Med Care. 1999;37:204–209. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199902000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Onega T, Duell EJ, Shi X, Demidenko E, Goodman D. Determinants of NCI Cancer Center Attendance in Medicare patients with lung, breast, colorectal, or prostate cancer. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;24:205–210. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0863-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang DC, Zhang Y, Mukherjee D, et al. Variations in referral patterns to high-volume centers for pancreatic cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:720–726. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy MM, Simons JP, Ng SC, et al. Racial differences in cancer specialist consultation, treatment, and outcomes for locoregional pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2968–2977. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0656-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayanga AJ, Waljee AK, Kaiser HE, Chang DC, Morris AM. Racial clustering and access to colorectal surgeons, gastroenterologists, and radiation oncologists by African Americans and Asian Americans in the United States: a county-level data analysis. Arch Surg. 2009;144:532–535. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayanga AJ, Kaiser HE, Sinha R, Berenholtz SM, Makary M, Chang D. Residential segregation and access to surgical care by minority populations in US counties. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:1017–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.01.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, Tate RC, Hargraves JL. Primary care physicians who treat blacks and whites. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:575–584. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa040609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morris AM, Rhoads KF, Stain SC, Birkmeyer JD. Understanding racial disparities in cancer treatment and outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhoads KF, Ngo JV, Ma Y, Huang L, Welton ML, Dudley RA. Do hospitals that serve a high percentage of Medicaid patients perform well on evidence-based guidelines for colon cancer care? J Health Care Poor U. 2013;24:1180–1193. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naylor K, Ward J, Polite BN. Interventions to improve care related to colorectal cancer among racial and ethnic minorities: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1033–1046. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2044-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mead EL, Doorenbos AZ, Javid SH, et al. Shared decision-making for cancer care among racial and ethnic minorities: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e15–e29. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, et al. The effect of race and sex on physicians' recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:618–626. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902253400806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Werner RM. Racial profiling: the unintended consequences of coronary artery bypass graft report cards. Circulation. 2005;111:1257–1263. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000157729.59754.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelly JJ, Chu SY, Diaz T, et al. Race/ethnicity misclassification of persons reported with AIDS. Ethn Health. 1996;1:87–94. doi: 10.1080/13557858.1996.9961773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swan J, Lillis S, Simmons D. Investigating the accuracy of ethnicity data in New Zealand hospital records: still room for improvement. N Z Med J. 2006;119:U2103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riddell T, Lindsay G, Kenealy T, et al. The accuracy of ethnicity data in primary care and its impact on cardiovascular risk assessment and management--PREDICT CVD-8. N Z Med J. 2008;121:40–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saunders CL, Abel GA, Turabi El A, Ahmed F, Lyratzopoulos G. Accuracy of routinely recorded ethnic group information compared with self-reported ethnicity: evidence from the English Cancer Patient Experience survey. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002882–e002882. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stewart SL, Swallen KC, Glaser SL, Horn-Ross PL, West DW. Comparison of methods for classifying Hispanic ethnicity in a population-based cancer registry. Am J Epidemiol. 1999;149:1063–1071. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aspinall PJ, Jacobson B. Why poor quality of ethnicity data should not preclude its use for identifying disparities in health and healthcare. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:176–180. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2006.019059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.United States Cancer Statistics: 1999–2008 Incidence and Mortality Web-Based Report. [Accessed December 2012];U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/uscs.