Abstract

Objective

To identify commonly reported symptoms in the lower limbs among those with or at-risk for developing lower limb lymphedema (LLL).

Design

We surveyed long-term cancer survivors using the Pennsylvania State cancer registry. We inquired about demographics, cancer treatment history, knowledge about LLL, and symptoms experienced since completing cancer treatment. We invited all participants for an in-person clinical assessment to better identify and characterize the symptoms associated with LLL.

Results

Response rate to our survey was 57.2%. Among the 107 participants who answered our survey, 37 reported ≥1 symptom associated with LLL (34.5%). Many reported a combination of symptoms that included difficulty walking (n=37; 100%), achiness (n=32; 86%), puffiness (n=28; 76%), and pain (n=27; 73%) on one side of the body since cancer treatment. In-person clinical assessment among a sub-sample of 17 participants revealed 10 participants with no evidence of LLL, and five and two participants with grade 1 and 2 LLL, respectively. In-person clinical assessment identified three cases of previously undiagnosed LLL.

Conclusions

One-third of cancer survivors surveyed reported experiencing new symptoms in the lower-limbs since cancer treatment. Cases of symptomatic, undiagnosed LLL may exist in the population.

Keywords: Adverse Effects, Lymphedema, Lymph Nodes, Radiation

INTRODUCTION

The American Cancer Society estimates that approximately 480,000 adults are diagnosed annually with melanomas or reproductive or gastrointestinal cancers for which treatments include irradiation and/or removal of lymph nodes from the groin or abdomen.1 A common concern for these cancer survivors is lymphedema of the legs and feet; known as lower limb lymphedema (LLL). LLL is an abnormal accumulation of protein rich fluid in the affected limb, which can occur after lymph node removal, trauma or irradiation.2, 3 This chronic, progressive condition has no known cure and has negative effects on wound healing, local blood flow, tissue oxygenation,4–6 as well as physical function and quality of life.7–9

The prevalence of LLL widely varies, depending on diagnostic criteria, intensity of lymph node treatment, and length of follow-up. Estimates suggest 20–30% of those with lymph node removal, trauma or irradiation to the groin or abdomen may develop LLL.10 Despite the large proportion of cancer survivors with or at-risk for LLL (~140,000 cancer survivors per year), scant research has examined symptoms in the legs and feet reported by cancer survivors with or at-risk for LLL.3, 11 This gap in evidence constrains clinicians’ ability to counsel their patients regarding the symptoms and physical impairments they may develop after surgery or radiation therapy.

To this end, we conducted a cross-sectional survey of cancer survivors diagnosed in the previous 3–5 years whose diagnoses and treatment placed them at increased risk of developing LLL. We inquired about common symptoms experienced in the legs and feet since completing cancer treatment.

METHODS

Population

In the spring of 2009, the Pennsylvania Cancer Registry was used to identify a random population-based sample of potentially eligible participants living in three Pennsylvania counties (Philadelphia, Montgomery, or Delaware) and in zip codes within 10 miles of the University of Pennsylvania. All potential participants were diagnosed with stage II–III cancer between 2004 and 2006 that included uterine, ovarian, cervical, endometrial, bladder, melanoma, penile, testicular, and colorectal cancers that might have included removal of lymph nodes or radiation of the abdomen or groin.1 The National Death Index was used to confirm that potentially eligible cancer survivors identified through the Pennsylvania cancer registry were alive at the time of the mailing. The University of Pennsylvania’s Institutional Review Board policies and approvals were rigorously adhered to throughout this research study. Participants provided informed consent by returning the completed survey, and completed written informed consent prior to the in-person clinical assessment.

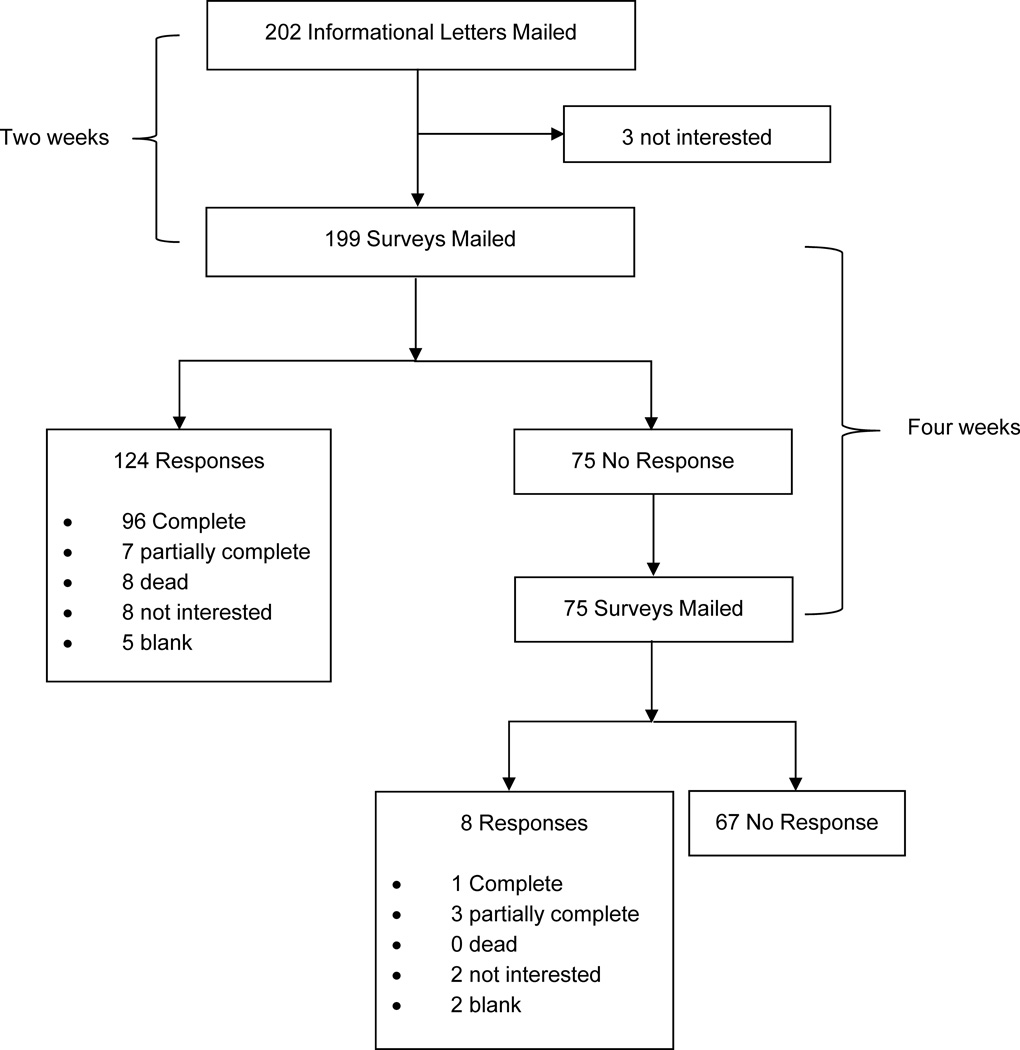

Mailed Survey

In the summer of 2009, we mailed letters to 202 cancer survivors with a brochure that explained the Pennsylvania Cancer Registry (available at registry website) and a cover letter informing them they would receive a mailed questionnaire asking them about the symptoms in their lower limbs. We asked eligible participants to inform us if they were not interested in participating in the study and receiving subsequent mailings. Two weeks later, a questionnaire was mailed to all cancer survivors who did not decline participation. This second letter included a cover letter explaining the purpose of the study, the study survey, postage paid self-addressed return envelope, and $1 attached to thank participants for their time. Four-weeks later, we mailed a third letter to participants who did not reply to the second mailing. No monetary remuneration was included in the third mailing.

The mailed survey asked questions about demographic characteristics (race, education, and occupation), cancer treatment history (type of cancer, treatment received, and history of lymphedema), and prior knowledge about LLL. We also asked about leg and foot symptoms that started after cancer treatment. We asked 18 specific leg and foot symptoms related to LLL. This questionnaire was based on the Norman Lymphedema Survey,12 a valid and reliable survey for diagnosing breast cancer related lymphedema (Table 1 see supplemental digital content for specific symptoms). The symptoms were revised to match those thought to be common to lower extremity lymphedema in consultation with the lead therapist for the Lymphedema Service at the University of Pennsylvania (over 20 years of lymphedema clinical experience).

Table 1.

Symptoms in the lower limbs in the previous 3-months:

|

Clinic Visit

We invited all participants who returned the mailed survey for a 30-minute in-person physical therapy examination at Penn Therapy and Fitness (located in Philadelphia, PA). This 30-minute examination included circumference measures of the legs and a standard physical therapy clinical examination of skin tissue tone and texture, and clinical history of leg symptoms. Patients were also asked whether they had any vascular disease diagnoses in order to delineate those for whom symptoms could be due to conditions other than lymphedema. Those who completed this in-person clinical assessment were remunerated $20 and told whether it was likely if their symptoms were consistent with a diagnosis of LLL in accordance with common toxicity criteria grading (CTCAE Version 3.0).13 If a participant appeared to have lymphedema, according to our in-person screening, we referred them for appropriate treatment and follow-up care.10

Statistical Analysis

We calculated percentages for the response rate for the letters mailed using methods described by the American Association for Public Opinion Research.14 We compared demographic, clinical characteristics, and number of leg and foot symptoms between the participants that had an in-person clinical examination versus those that did not. Categorical variables are presented using rates (%) and were compared between groups using Fishers exact test. Continuous variables are presented using means ± standard deviation or median and interquartile range, and were compared between groups using Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Statistical significance was established at p<0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 12.0 (College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Mailed Survey Results

We mailed 202 informational letters to eligible cancer survivors. Three potentially eligible participants were not interested in participating in our survey. We mailed 199 and 75 surveys in the first and second cycles of mailing. The response rate to our mailed surveys was 57.2% (Figure 1). We received 97 completed surveys, and 10 partially completed surveys to contribute to the subsequent data analysis (107 surveys in total). The level of education varied among participants, and the majority reported being retired (Table 2). Among the 107 participants, 78% reported being unsure or never hearing about lymphedema (Table 3). Eighteen percent did not know if they had lymph nodes removed for their cancer treatment.

Figure 1.

Flow of mailings to potentially eligible participants

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of participants in study

| Variable | Total sample (n=107) |

Did not come to clinic (n=90) |

Came to clinic (n=17) |

p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age — yr | 69.3±12.6 | 69.1±14.3 | 63.0±12.5 | 0.03 |

| Education | 0.02 | |||

| High school or less | 52 (50%) | 47 (53%) | 6 (35%) | |

| Some college | 16 (16%) | 30 (34%) | 4 (24%) | |

| College degree or more | 34 (33%) | 11 (13%) | 7 (41%) | |

| Self-reported race | 0.66 | |||

| White | 56 (53%) | 49 (54%) | 7 (44%) | |

| Black | 41 (39%) | 34 (38%) | 7 (44%) | |

| Other | 9 (8%) | 8 (9%) | 3 (12%) | |

| Occupation | 0.02 | |||

| Professional | 18 (16%) | 10 (11%) | 8 (47%) | |

| Clerical or service | 18 (16%) | 16 (17%) | 2 (12%) | |

| Homemaker, student, or unemployed | 8 (7%) | 7 (8%) | 1 (6%) | |

| Other or unknown | 10 (7%) | 9 (10%) | 1 (6%) | |

| Retired | 56 (51%) | 51 (55%) | 5 (30%) |

examining differences between those that came to clinic versus did-not using rank-sum and Fishers exact test. Values are means ±SD or percentage (%). May not sum to 100% due to rounding error and non-item response.

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics of participants in study

| Variable | Total sample (n=107) |

Did not come to clinic (n=90) |

Came to clinic (n=17) |

p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of cancer | 0.992 | |||

| Bladder | 44 (41%) | 37 (84%) | 7 (16%) | |

| Uterine | 15 (14%) | 13 (87%) | 2 (13%) | |

| Ovarian | 14 (13%) | 12 (86%) | 2 (14%) | |

| Cervical | 12 (11%) | 9 (75%) | 3 (25%) | |

| Endometrial | 12 (11%) | 10 (83%) | 2 (17%) | |

| Testicular | 4 (4%) | 3 (75%) | 1 (25%) | |

| Colon | 2 (2%) | 2 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Kidney | 1 (1%) | 2 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Other sites | 3 (3%) | 3 (100%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Lymph nodes removed | 0.85 | |||

| Yes | 30 (29%) | 24 (28%) | 6 (35%) | |

| No | 54 (53%) | 45 (53%) | 9 (53%) | |

| Not sure | 18 (18%) | 16 (19%) | 2 (12%) | |

| Radiation treatment | 0.16 | |||

| Yes | 38 (37%) | 29 (35%) | 9 (53%) | |

| No | 63 (62%) | 54 (64%) | 8 (47%) | |

| Not sure | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Have you ever heard about lymphedema | 0.25 | |||

| Yes | 23 (23%) | 16 (19%) | 7 (41%) | |

| No | 74 (73%) | 64 (75%) | 10 (59%) | |

| Not sure | 5 (5%) | 5 (6%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Ever been told you have lymphedema | 0.02 | |||

| Yes | 6 (6%) | 2 (2%) | 4 (24%) | |

| No | 90 (90%) | 78 (93%) | 12 (71%) | |

| Not sure | 5 (4%) | 4 (5%) | 1 (6%) | |

| Received treatment for lymphedema | 0.18 | |||

| Yes | 7 (7%) | 3 (4%) | 4 (24%) | |

| No | 89 (87%) | 76 (89%) | 13 (76%) | |

| Not sure | 6 (5%) | 6 (7%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Median [IQR] lymphedema symptoms | 0 [0–4] | 0 [0–3] | 4 [3–9.5] | 0.004 |

Results are No. (%) or median [IQR] where noted.

examining differences between those that came to clinic versus did-not using Fishers exact and rank-sum test. May not sum to 100% due to rounding error and non-item response.

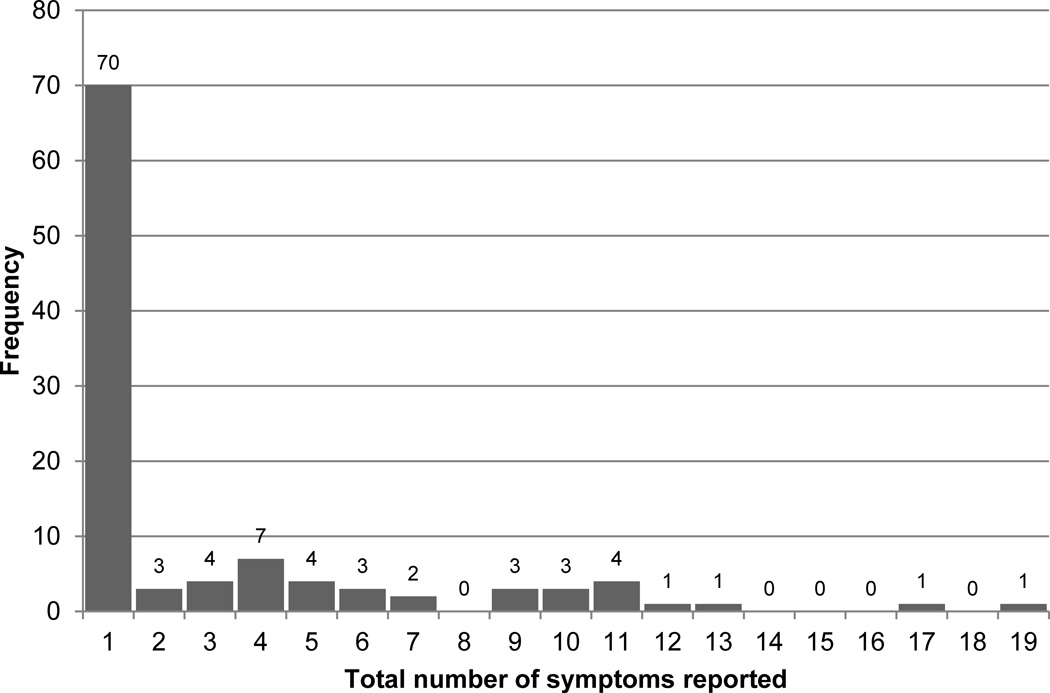

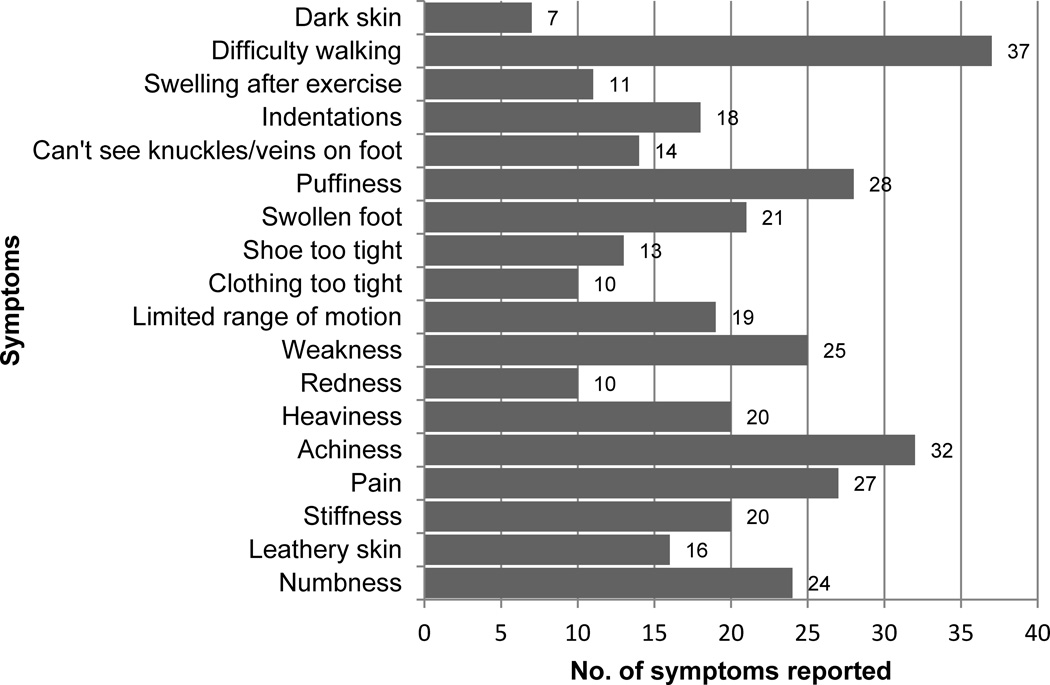

The next section of our survey inquired about symptoms experienced in the lower limbs. The number of self-reported symptoms ranged from 0–18, and was highly skewed (Figure 2). Among those with a prior diagnosis of LLL, the median number of self-reported symptoms was two [interquartile range: 0–10]. Median number of self-reported symptoms did not statistically differ between those with versus without a prior diagnosis of LLL; p=0.21. Among the 107 cancer survivors who answered our survey, 37 reported ≥1 symptom (34.5%). The most common symptoms associated with LLL were difficulty walking (n=37; 100%), achiness (n=32; 86%), puffiness (n=28; 76%), and pain (n=27; 73%) on one side of the body since cancer treatment (Figure 3). Among the 37 cancer survivors experiencing symptoms associated with LLL, 30 (81%) had ≥3 symptoms. Among the 30 participants reporting ≥3 symptoms, 18 (60%) were ≥65 years old (p=0.05).

Figure 2.

Distribution of nubber of symtpoms reported in previous 3-months (n=107)

Figure 3.

Symptoms reported on one side of body in previous 3-months (n=107)

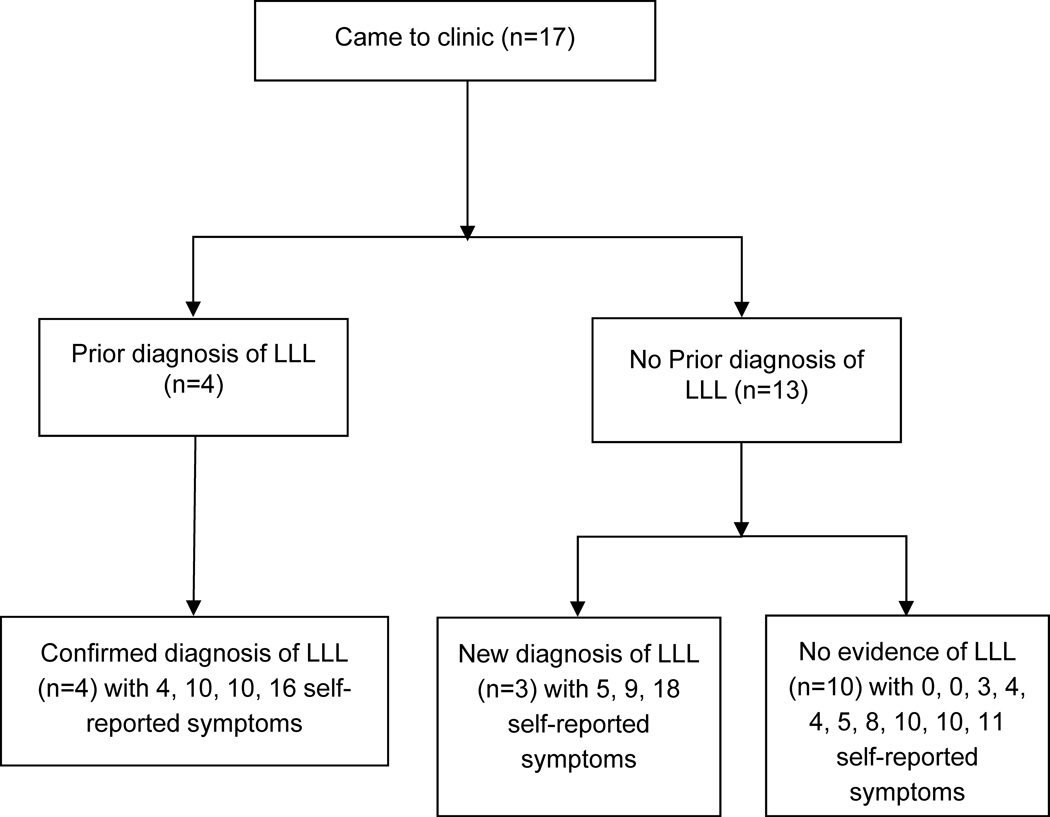

In-person clinical assessment

We invited all 107 participants who completed all or part of our mailed survey to have an in-person clinical assessment, 17 attended (16%). Those who came to the clinic were younger, and had professional occupation (Table 2). Those who came to the clinic were more likely to have a previous diagnosis of LLL, and to report more symptoms associated with LLL (Table 3). In accordance with the common toxicity criteria version 3.0, among the 17 participants who underwent an in-person clinical assessment, 10 participants showed no evidence of LLL, 5 and 2 participants showed evidence of grade 1, and 2 lymphedema, respectively.13 We identified three cases of previously undiagnosed LLL aged 63, 70, 71 years old, with 9, 5, and 18 self-reported symptoms, respectively (Figure 4). In-person clinical assessment identified 10 participants with no evidence of LLL, yet these participants reported an average of 5.5 symptoms in their lower limbs since cancer treatment. All 17 participants said they would be interested in participating in an LLL exercise rehabilitation program if it were to become available.

Figure 4.

Distribution of diagnoses and symptoms frequency among those who attended an in-person clinical assessment

DISCUSSION

The major finding of this study is that 78% of cancer survivors surveyed reported being unsure or never hearing about LLL. Additionally, 35% of long-term cancer survivors in our sample reported ≥1 symptom in their legs or feet for which onset occurred after completing cancer treatment. Among the 37 who reported symptoms, 30 (81%) reported ≥3 symptoms. Among the six participants who reported a previous diagnosis of LLL, three (50%), reported ≥3 symptoms, with 4, 10, and 16 self-reported symptoms. The most common symptoms reported were difficulty walking, achiness, puffiness, and pain. Using in-person clinical assessments among a self-selected sub-sample of 17 participants, we identified three cases of previously undiagnosed LLL.

In a prior report among 231 gynecologic cancer survivors surveyed three months to five years post diagnosis, 25% stated they would want to be more informed about the causes, prevention, and treatment of LLL.11 Twenty five percent also indicated they would like written information about ways to manage symptoms of LLL; 19% indicated they would like assistance in managing the symptoms associated with LLL; and 12% indicated needing help in managing the symptoms of LLL at work, and in completing activities of daily living at home. In our sample, among those who attended an in-person clinical assessment, 100% said they would be interested in participating in a physical rehabilitation program if such a resource becomes available in the future.

Substantiating the self-reported functional impairments reported in our sample, a small pilot study (n=10) of cancer survivors with LLL observed 6-minute walk distance and single leg stands were 30% and 12% lower than age-matched normative values, respectively.9 However, during this pilot study two of the ten participants (20%) were diagnosed with cellulitis, a bacterial infection requiring broad-spectrum antibiotics and cessation of exercise. It is unknown if the two reported cases of cellulitis were directly related to exercise training, the environment in which the exercise training was performed, or unrelated to exercise entirely. Therefore, the risk to benefit ratio of exercise or physical activity remains to be elucidated. Conversely, among breast cancer survivors with upper limb lymphedema, weight-lifting exercise is known to be safe, and known to reduce lymphedema exacerbations and lymphedema symptom severity.15 It is plausible that cancer survivors who engage in more physical activity report fewer, less intense, more-transient, symptoms and side effects associated with LLL. Research is needed to establish the safety, feasibility, and efficacy of prevention and treatment rehabilitation interventions for cancer survivors with lower extremity symptoms, including those with LLL.

Despite common assumptions, numerous differences exist between LLL and upper limb lymphedema reported by breast cancer survivors. Anatomic and hemodynamic differences exist, such that the lower limbs need to move a larger volume of lymphatic fluid over a longer distance compared to the arm.18 Previous reports among upper limb lymphedema suggest avoiding use of the affected limb;19 this recommendation has been questioned given the emerging evidence of the safety of upper body weight lifting among breast cancer survivors with or at-risk for upper limb lymphedema.15, 20 Nonetheless, avoiding affected arm use (i.e., carrying groceries) may be easier than avoiding lower limb use (i.e., walking). Further, LLL may be confused with lower limb venous disease, making diagnosis and treatment more complex than upper limb lymphedema.18 These anatomic, physiologic, and functional differences between LLL and upper limb lymphedema provide rationale for establishing a foundation of evidence that provides as much depth and breadth as seen among upper limb lymphedema,21–24 with the goal of providing evidence based clinical recommendations and interventions among those with or at-risk for LLL.

Cancer survivors are living longer after diagnosis of cancer because of improved surgical, chemotherapeutic, and radiation techniques. The increasing number of cancer survivors living ≥5 years after diagnosis has provided numerous challenges to the cancer survivor as they attempt to reap high qualities-of-life while traversing the immediate and late side effects that result from cancer treatment.16 For example, the mean number of lymph nodes removed among those with uterine corpus malignancies at a large metropolitan cancer center increased from four in 1994, to 18 in 2003.3 This 350% increase in removal of lymph nodes provides the capacity for better treatment through increased pathologic evidence for diagnostic tumor staging of cancer. However, this increase was associated with an increased rate of LLL (<1% in 1994 compared to 6% in 2003). The percentage of patients at this metropolitan cancer center with ≥10 lymph nodes removed increased from 8% in 1993, to 70% in 2003.3 Surgical removal of lymph nodes is an established risk factor for LLL, increasing risk by 2–3-fold among gynecologic cancers in dose-response fashion with number of lymph nodes removed.2, 11 Therefore, patients receiving surgery and lymph node removal need education about the signs and symptoms of LLL, the likelihood of experiencing these signs and symptoms, and knowledge of interventions to manage these signs and symptoms, once identified. To date, few such interventions exist.9, 10 A 20-item questionnaire designed to identify cases of LLL was recently published.17 The questionnaire is self-administered, and takes <10 minutes to complete. Providing a questionnaire to cancer survivors who are at-risk for developing LLL at routine follow up appointments may aid to identify symptoms to diagnose and treat LLL in a timely manner.

Risk reduction practices to minimize the risk of LLL onset or flare-up are similar to those with upper limb lymphedema,10, 23 despite the above-discussed anatomic, physiologic, and functional differences.18 These practices include avoiding constriction, infection, inflammation, increases in lymphatic circulation, and using caution during air travel. LLL may occur months or years after surgery, therefore these risk reduction practices should become habitual to reduce risk of eliciting an onset of LLL. We remind readers that swollen lower limbs are not exclusively indicative of LLL. Swollen lower limbs may suggest deep vein thrombosis or congestive heart failure particularly among older cancer survivors with existing co-morbid conditions.18 Therefore, all patients should be encouraged to call their healthcare provider if they experience any change in LLL symptoms. Our sample reported numerous symptoms in the lower limbs since completing cancer treatment. Furthermore, among the 17 participants who underwent an in-person clinical examination, three cases of previously undiagnosed LLL were identified (18%). This is consistent with a previous report that identified 14% of gynecologic cancer survivors with undiagnosed lower limb swelling.11 This evidence is consistent with the hypothesis of an existing gap in communication between patients and healthcare providers, which is likely due to the insufficient foundation of evidence tailored to LLL.

The major limitation to this study is the most prevalent symptoms identified in our survey; achiness, difficulty walking, pain, puffiness, and weakness, are more frequently caused by exceedingly common (especially among older patients) non-lymphedema conditions, such as osteoarthritis, and diabetic neuropathy, which limits our knowledge of LLL specific symptoms. This may provide one explanation as to why participants who attended the in-person clinical assessment who did not have evidence of LLL reported an average of 5.5 symptoms in the lower limbs. The survey did not inquire about comorbidities that are associated with the most prevalent symptoms; therefore we cannot conclude these symptoms are indicative of LLL or other non-lymphedema conditions. Nonetheless, a proportion of cancer survivors experience a burden of symptoms in their lower limbs that occur after cancer treatment.

Other limitations to our study include the possibly for volunteer bias in responding to our mailed letter. It is plausible the cancer survivors who did not reply to our survey were different from those who did reply. It is plausible that cancer survivors did not accurately self-report their symptoms, over or underestimating the number of symptoms experienced. Some symptoms may be transient, and participants may have only recalled the symptoms they experienced recently or at the time of completing our survey, or the symptoms that impaired physical function or quality of life to the greatest extent. We identified age, occupation, previous diagnosis of LLL, and number of self-reported symptom as differences among participants who volunteered to attend an in-person clinical assessment versus those who did not volunteer. We anticipated inviting all participants for an in-person clinical assessment; this is why we limited our sampling framework to eligible cancer survivors living in zip codes within a 10-mile radius round the University of Pennsylvania. It is plausible cancer survivors living in this geographic region are different from other cancer survivors for a variety of reasons (i.e., access to healthcare facilities, living conditions, etc.) limiting the generalizability of our findings. It is plausible those who attended an in-person clinical assessment had greater awareness or concerns about their current symptoms compared to those who did not attend an in-person clinical assessment.

CONCLUSION

Our study surveyed cancer survivors who may be at increased risk for LLL, based on primary tumor site and common treatments for those tumors. This data suggest a large proportion of cancer survivors are unaware of LLL and unaware of the signs and symptoms associated with LLL. Our sample self-reported a variety of symptoms occurring after cancer treatment that may impair quality of life and physical functioning. There may be a subgroup of cancer survivors without LLL, yet report symptoms in their lower limbs. The likelihood that there is an underdiagnosis of LLL is supported by the empirical observation of identifying three previously undiagnosed cases, simply by offering an in-person clinical assessment.

In conclusion, those with a change in lower extremity symptoms should inform their healthcare provider for evaluation for possible LLL or other conditions amenable to medical and rehabilitative interventions. Among those who are recently diagnosed with cancer, healthcare providers to strive to inform their patients of the likelihood for experiencing the array of symptoms that may be experienced after cancer treatment. Future interventions need to explore safety and efficacy of physical rehabilitation to prevent and/or treat cases of LLL.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None

Footnotes

Disclosures:

Financial disclosure statements have been obtained, and no conflicts of interest have been reported by the authors or by any individuals in control of the content of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59(4):225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tada H, Teramukai S, Fukushima M, Sasaki H. Risk factors for lower limb lymphedema after lymph node dissection in patients with ovarian and uterine carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abu-Rustum NR, Alektiar K, Iasonos A, et al. The incidence of symptomatic lower-extremity lymphedema following treatment of uterine corpus malignancies: A 12-year experience at memorial sloan-kettering cancer center. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103(2):714–718. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.03.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brorson H, Svensson H. Skin blood flow of the lymphedematous arm before and after liposuction. Lymphology. 1997;30(4):165–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stanton AW, Levick JR, Mortimer PS. Cutaneous vascular control in the arms of women with postmastectomy oedema. Exp Physiol. 1996;81(3):447–464. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1996.sp003948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daroczy J. Pathology of lymphedema. Clin Dermatol. 1995;13(5):433–444. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(95)00086-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ryan M, Stainton MC, Jaconelli C, Watts S, MacKenzie P, Mansberg T. The experience of lower limb lymphedema for women after treatment for gynecologic cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30(3):417–423. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.417-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frid M, Strang P, Friedrichsen MJ, Johansson K. Lower limb lymphedema: Experiences and perceptions of cancer patients in the late palliative stage. J Palliat Care. 2006;22(1):5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz E, Dugan NL, Cohn JC, Chu C, Smith RG, Schmitz KH. Weight lifting in patients with lower-extremity lymphedema secondary to cancer: A pilot and feasibility study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91(7):1070–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langbecker D, Hayes SC, Newman B, Janda M. Treatment for upper-limb and lower-limb lymphedema by professionals specializing in lymphedema care. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2008;17(6):557–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2007.00878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beesley V, Janda M, Eakin E, Obermair A, Battistutta D. Lymphedema after gynecological cancer treatment : Prevalence, correlates, and supportive care needs. Cancer. 2007;109(12):2607–2614. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norman SA, Miller LT, Erikson HB, Norman MF, McCorkle R. Development and validation of a telephone questionnaire to characterize lymphedema in women treated for breast cancer. Phys Ther. 2001;81(6):1192–1205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szuba A, Rockson SG. Lymphedema: Classification, diagnosis and therapy. Vasc Med. 1998;3(2):145–156. doi: 10.1177/1358836X9800300209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly BJ, Fraze TK, Hornik RC. Response rates to a mailed survey of a representative sample of cancer patients randomly drawn from the pennsylvania cancer registry: A randomized trial of incentive and length effects. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel A, et al. Weight lifting in women with breast-cancer-related lymphedema. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(7):664–673. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Earle CC. Failing to plan is planning to fail: Improving the quality of care with survivorship care plans. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5112–5116. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carter J, Raviv L, Appollo K, Baser RE, Iasonos A, Barakat RR. A pilot study using the gynecologic cancer lymphedema questionnaire (GCLQ) as a clinical care tool to identify lower extremity lymphedema in gynecologic cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;117(2):317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen MR, Simonsen L, Karlsmark T, Bulow J. Lymphoedema of the lower extremities--background, pathophysiology and diagnostic considerations. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2010;30(6):389–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2010.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Susan G. Komen for the Cure. [Accessed June 20, 2012];Lymphedema. http://ww5.komen.org/BreastCancer/Lymphedema.html. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel AB, et al. Weight lifting for women at risk for breast cancer-related lymphedema: A randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304(24):2699–2705. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Lymphedema Network Medical Advisory Committee. Position Statement of the National Lymphedema Network. Topic: Exercise. [Accessed June 20, 2012]; http://www.lymphnet.org/pdfDocs/nlnexercise.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Lymphedema Network Medical Advisory Committee. Position State of the National Lymphedema Network. Topic: Training of Lymphedema Therapists. [Accessed June 20, 2012]; http://www.lymphnet.org/pdfDocs/nlntraining.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Lymphedema Network Medical Advisory Committee. Position Statement of the National Lymphedema Network. Topic: Lymphedema Risk Reduction Practices. [Accessed June 20, 2012]; http://www.lymphnet.org/pdfDocs/nlnriskreduction.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Lymphedema Network Medical Advisory Committee. Position Statement of the National Lymphedema Network. Topic: The Diagnosis and Treatment of Lymphedema. [Accessed June 20, 2012]; http://www.lymphnet.org/pdfDocs/nlntreatment.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.