Trigeminal neuralgia is an extremely painful condition. Treatment options for trigeminal neuralgia include anticonvulsants, opioids and surgical methods; however, some cases may be refractory to these therapies. In this article, the authors report a case involving a patient for whom conventional treatments failed; she underwent a successful trial of peripheral nerve stimulation and subsequently opted for a permanent implantation of an internal pulse generator, leading to long-term relief of her pain.

Keywords: Peripheral neuromodulation, Trigeminal neuralgia

Abstract

Trigeminal neuralgia is a type of orofacial pain that is diagnosed in 150,000 individuals each year, with an incidence of 12.6 per 100,000 person-years and a prevalence of 155 cases per 1,000,000 in the United States. Trigeminal neuralgia pain is characterized by sudden, severe, brief, stabbing or lancinating, recurrent episodes of pain in the distribution of one or more branches of the trigeminal nerve, which can cause significant suffering for the affected patient population.

In many patients, a combination of medication and interventional treatments can be therapeutic, but is not always successful. Peripheral nerve stimulation has gained popularity as a simple and effective neuromodulation technique for the treatment of many pain conditions, including chronic headache disorders. Specifically in trigeminal neuralgia, neurostimulation of the supraorbital and infraorbital nerves may serve to provide relief of neuropathic pain by targeting the distal nerves that supply sensation to the areas of the face where the pain attacks occur, producing a field of paresthesia within the peripheral distribution of pain through the creation of an electric field in the vicinity of the leads.

The purpose of the present case report is to introduce a new, less-invasive interventional technique, and to describe the authors’ first experience with supraorbital and infraorbital neurostimulation therapy for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia in a patient who had failed previous conservative management.

Abstract

La névralgie du trijumeau est un type de douleur buccofaciale diagnostiquée chez 150 000 personnes chaque année, pour une incidence de 12,6 cas sur 100 000 personnes-année et une prévalence de 155 cas sur 1 000 000 habitants des États-Unis. La névralgie du trijumeau se caractérise par des douleurs aiguës violentes, brèves et soudaines ou par des épisodes récurrents de douleurs lancinantes le long d’au moins une ramification du nerf trijumeau, ce qui provoque des souffrances importantes pour la population de patients touchée.

Chez de nombreux patients, une association de médicaments et de traitements d’intervention peut se révéler thérapeutique, mais pas toujours. La stimulation des nerfs périphériques a gagné en popularité, car c’est une technique de neurostimulation simple et efficace pour traiter de nombreuses douleurs, y compris les céphalées chroniques. Dans le cas de la névralgie du trijumeau, la neurostimulation des nerfs sus-orbitaire et infra-orbitaire pourrait soulager la douleur neuropathique en ciblant les nerfs distaux qui transmettent la sensation dans les régions du visage où les crises de douleur se manifestent et qui produisent un champ de paresthésie dans la distribution périphérique de la douleur grâce à la création d’un champ électrique à proximité des dérivations.

Le présent rapport de cas vise à présenter une nouvelle technique d’intervention moins effractive et à décrire la première expérience des auteurs avec la thérapie par neurostimulation sus-orbitaire et infra-orbitaire pour traiter la névralgie du trijumeau chez un patient réfractaire à un traitement prudent.

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is characterized by sudden, severe, brief, stabbing or lancinating, recurrent episodes of pain in the distribution of one or more branches of the trigeminal nerve (1). According to the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, TN is diagnosed in 150,000 individuals each year; the incidence is 12.6 per 100,000 person-years and the prevalence is 155 cases per 1,000,000 in United States, with female sex and age >50 years being two common risk factors (2). The clinical course of TN is variable, with recurrence being common and some patients experiencing continuous pain.

There are several classifications systems for TN relating to specific causes. As per the International Headache Society (International Classification of Headache Disorders – Beta, 2013) and the American Academy of Orofacial Pain (2013), orofacial pain can be classified as classical TN or painful trigeminal neuropathy. Classical TN can be purely paroxysmal or with concomitant persistent facial pain. Painful trigeminal neuropathy can be caused by acute herpes zoster, postherpetic, post-traumatic, multiple sclerosis-related or attributed to space-occupying lesions (3). The present discussion will focus specifically on classical TN, which can develop without apparent cause other than neurovascular compression. According to the International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (3), the following criteria must be met for diagnosis:

At least three attacks of unilateral facial pain fulfilling criteria 2 and 3;

Occurring in one or more divisions of the trigeminal nerve, with no radiation beyond the trigeminal distribution;

- Pain has at least three of the following four characteristics:

- recurring in paroxysmal attacks lasting from a fraction of a second to 2 min;

- severe intensity;

- electric shock-like, shooting, stabbing or sharp in quality;

- precipitated by innocuous stimuli to the affected side of the face.

No clinically evident neurological deficit;

Not better accounted for by another International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition, diagnosis (2).

As mentioned, classical TN can be further characterized as purely paroxysmal, which is usually initially responsive to pharmacotherapy, or classical TN with concomitant persistent facial pain, which fulfills the diagnostic criteria of classical TN along with persistent facial pain of moderate intensity in the affected region. The latter has shown poor response to medical treatment.

From etiological and pathophysiological viewpoints, TN is either idiopathic or symptomatic; ie, patients with typical ‘tic douloureux’ but without demonstrable lesions (idiopathic TN, which can be episodic [type 1] or constant [type 2]), and patients with trigeminal pains, not necessarily paroxysmal, secondary to a well-documented pathology (symptomatic trigeminal pain) (4). It has been suggested that medical treatment to control pain in patients with TN should include carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine, with very little benefit observed among patients who were tried on other oral agents (5). For patients who are refractory to medical treatment, neurosurgical methods, such as micro-vascular decompression, rhizotomies or radiosurgery, may be considered. Microvascular decompression can be considered over other surgical procedures to provide the longest duration of pain relief (6). Although surgical therapy for TN is generally well tolerated, a potential complication is anesthesia dolorosa, a condition characterized by persistent, painful anesthesia or hyperesthesia in the denervated region, which can be more intolerable than the pain from TN itself (7).

Disruption of the balance between peripheral and central nociception mechanisms has been implicated as the etiology for many cranio-facial headache disorders (8).

Neurostimulation for primary headaches has been increasingly utilized as a treatment modality. It involves signal modification of intrinsic electrical impulses with exogenous electrical stimulation (9). Considerable progress has been made in the application of neurostimulation therapy to treat medically intractable chronic headaches. The use of posterior hypothalamic deep brain stimulation with implantation of brain electrodes with the aim of inhibiting hyperactive neurons has been used to treat the central modality of chronic headaches, such as cluster headaches and short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache with conjunctival injection and tearing, with effective relief (10,11). Current therapies to target peripheral nerves include occipital nerve stimulation with the use of implanted pulse generators for the treatment of occipital neuralgia and other facial painful syndromes (12,13), as well as vagal nerve stimulation for the treatment of migraine attacks (14). Because a prospective study involving device implantation would be difficult to conduct for ethical reasons, the purpose of the present case report is to introduce a new interventional technique to describe our first experience with supraorbital and infraorbital neurostimulation therapy for the treatment of TN.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 38-year-old woman with refractory TN was referred to the authors’ pain clinic due to constant mild to moderate lancinating pain with episodic paroxysm of severe lancinating pains in the trigeminal distribution. The patient was referred for a Gasserian ganglion radiofrequency rhizotomy following a successful local anesthetic block. Previous unsuccessful treatments had included microvascular decompression, Gamma Knife radiosurgery and percutaneous balloon compression, without relief. On presentation, the patient complained of sharp pain located in the left side of her face, especially the forehead and maxillary region. At the time of evaluation, using a visual analogue pain scale (in which a score of 10 represents the worst pain), she described the pain as being a 7. On further questioning, she described the pain as being a 10 at its worst and a 5 at its best, with periods of additional intermittent severe lancinating, electrical and stabbing pains. The patient’s current medical regimen included carbamazepine 600 mg orally twice per day, topiramate 200 mg orally twice per day, baclofen 20 mg orally three times per day, oxycodone 10 mg orally every 6 h, and hydrocodone 10 mg orally every 6 h for breakthrough pain. Although the patient was compliant with the treatment prescribed, she was obtaining little relief from it. After explanation of the therapeutic options, risks and benefits, the patient elected to pursue peripheral neuromodulation as the next step in her management, with the expected benefit of improvement in her pain. A trial of peripheral nerve stimulation of the supraorbital, supratrochlear and infraorbital nerves was then performed in the operating room using monitored anesthesia. After skin preparation with iodine, sterile drapes were placed and a small incision was made posterior to the point of temporal artery palpation. The incision was deepened into the subcutaneous tissue using electrocautery until the fascia of the temporal muscles was reached. Using fluoroscopic guidance, a standard Touhy needle was then advanced in the epifascial plane to the vicinity over-lying the supratrochlear and supraorbital nerves.

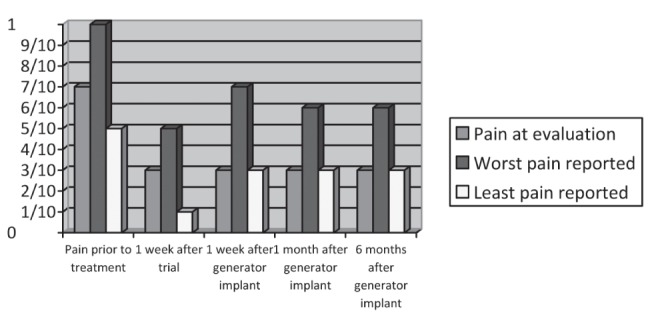

A Linear ST electrode (model SC-2218-50cm [Boston Scientific, USA]) was left in place while the Touhy needle was removed. Sedation was lightened and the area of coverage was deemed acceptable following a test of stimulation. The same procedural approach was then repeated for the infraorbital nerve. The tip of the electrode was then placed approximately 2 cm from the lateral aspect of the nose. The leads were tunnelled with the dedicated Touhy needle around the ear and down the neck to the infraclavicular area, where the battery was to be eventually implanted if the trial was deemed successful. No extensions were used to avoid erosions. The patient underwent a five-day trial period, at the end of which she reported her pain to be approximately 50% improved, reporting her pain to be a 3 of 10 at the time of evaluation, with scores of 5 of 10 at the worst and 1 of 10 at the least. Seven days following the successful trial, the patient decided to proceed with permanent internal pulse generator implantation in the anterior chest region under general anesthesia with the same leads. Six months after the procedure, the patient reported lasting relief and overall satisfaction with her treatment (chronological assessment of the patient’s analgesic progress are presented in Table 1 and Figure 1). The patient continues to experience pain relief and improvement in terms of patient satisfaction one year after implantation. Her antineuropathic medications (carbamazepine, topiramate and baclofen) have been continued at the original preimplantation doses; the rest of the pain medication that she was taking previously (oxycodone and hydrocodone) has been discontinued. To date, side effects have not been noted.

TABLE 1.

Chronological assessment of patient’s analgesic progress based on visual analogue scale scores

| Evaluation | Pain at evaluation* | Worst pain reported* | Least pain reported* | Patient’s global impression of pain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before implantation | 7 | 10 | 5 | (Baseline) |

| One week after trial implantation | 3 | 5 | 1 | Very much improved |

| One week after generator implantation | 3 | 7 | 3 | Very much improved |

| One month after generator implantation | 3–4 | 6–7 | 3 | Very much improved |

| Six months after generator implantation | 3–4 | 6–7 | 3 | Very much improved |

All pain scores based on a visual analogue scale (scored from 0 to 10)

Figure 1).

Chronological assessment of the patient’s analgesic progress based on visual analogue scale scores

DISCUSSION

Classical TN is described as developing without any apparent cause other than neurovascular compression. Compression of the protective myelin sheath of the nerve causes erratic and hyperactive functioning of the nerve. This can lead to pain attacks at the slightest stimulation of any area served by the nerve and can hinder the ability of the nerve to terminate the pain signals after the stimulation ends (15).

Peripheral nerve stimulation has gained popularity as a simple and effective neuromodulation technique for treating chronic headache disorders. Classically, peripheral nerve stimulation is a procedure that targets a single nerve and attempts to produce a paresthesia that spreads along the territory innervated by the stimulated nerve (16). It involves signal modification of intrinsic electrical impulses with exogenous electrical stimulation. Melzack and Wall (17) first proposed the ‘gate control theory’ in 1965. The theory states that competing nociceptive and innocuous signals influence second-order neurons to transmit pain signals for higher processing. Summation of nociceptive signals across trigeminal nerve divisions has been shown to heighten overall pain perception (18). Changes in cerebral blood flow have been demonstrated by positron emission tomography imaging within the anterior cingulate cortex and left pulvinar during occipital nerve stimulation (19). Treatment success in these areas suggest that stimulation of the supra- and infraorbital nerves may also alleviate the pain associated with TN. A reduction in pain intensity ≥50% is considered to represent a successful procedure.

The four most common indications for peripheral nerve stimulation applicable to the craniofacial region that have been described in the literature are postherpetic neuralgia involving the territory of the trigeminal nerve (20,21), post-traumatic or postsurgical neuropathic pain that is related to an underlying dysfunction of the infraorbital, supraorbital (22) or occipital nerve, ‘transformed migraine’ presenting with occipital pain and discomfort, and occipital neuralgia or cervicogenic occipital pain (23). Knowledge of the anatomical location of the nerve is used for placement of electrodes over the path of the peripheral nerve that supplies the painful area, which is involved in the generation of pain. Alternatively, ultrasound guidance has been recommended. In one study, a reliable estimate of the function of the trigeminal nerve by means of evoked potentials has been described. The infraorbital nerve was electrically stimulated and served as a method to assess the function of the part of trigeminal pathway between the infraorbital nerve and the brainstem. It demonstrated that the infra-orbital nerve trunk gives rise to very reliable scalp responses reflecting the activity of the afferent pathway between the maxillary nerve and the brain stem (18). Several case reports have also described the effectiveness of supraorbital nerve stimulation in the management of cluster headache (24,25). This is a relatively simple, minimally invasive and reversible modality of treatment that may be effective in the management of otherwise one of the most devastating headaches that one can experience. Given these data, the use of the supraorbital and infraorbital nerves as the target of neurostimulation for the treatment of TN, as illustrated in the present case, may serve useful for treating the neuropathic pain associated with TN by targeting the distal nerves that supply sensation to the areas of the face where the pain attacks occur. It can produce a field of paresthesia within the peripheral distribution of pain by creating an electric field in the vicinity of the leads (13). Because the supraorbital and infraorbital nerves are functional parts of the trigeminocervical complex, their stimulation may inhibit central nociceptive transmission and provide pain relief (26,27). Other proposed mechanisms of pain relief include subcutaneous electrical conduction, dermatomal and myotomal electrical stimulation, partial sympathetic blockade and local blood flow alteration (28,29).

Another component to be considered is the placebo effect, which influences patient outcomes after any treatment, including surgery, that the clinician and patient believe to be effective. Placebo effects (also cited as nonspecific effects of treatment), plus disease natural history and regression to the mean can result in high rates of good outcomes, which may be misattributed to specific treatment effects. Classically, an improvement superior to one-third compared with placebo has been considered to indicate a successful treatment, although the true causes of improvements in pain after treatment remain unknown in the absence of independently evaluated randomized controlled trials (30).

Regarding side effects, the complication rate for peripheral nerve stimulation when paddle surgical leads are used is low, although some complications have been reported, including local infection, sepsis, hardware erosion, component disconnection, electrode fractures and displacements. Some of the reported complications include lead displacement (5% to 26%, depending on the type of leads used), battery failure due to depletion, infection (4%), increased pain at the lead or generator sites, and even total relief of pain with the device turned off, eventually requiring the explantation of the device in the latter two cases (31).

The preliminary outcomes from this procedure suggest that this may be a less invasive alternative to surgical interventions in carefully selected patients when other conservative measures have failed. The patient’s visual analogue scale scores improved significantly and her intake of pain medication diminished (opiates have been discontinued). The patient feels very much improved, her quality of life is better and she has been able to return to her daily activities.

Although further research investigating long-term effectiveness and the results in a large group of patients may be warranted, a cost-benefit analysis suggested that peripheral nerve stimulation is associated with long-term economic benefits secondary to the decrease in health care utilization after the stimulator is placed (27). Thus, this technique may provide a useful alternative that may be cost effective in patients who have failed conservative alternative measures. In addition, this patient may have avoided other interventions had this interventional technique been attempted earlier in the patient’s treatment course.

CONCLUSION

Peripheral nerve stimulation as a treatment modality for TN is witnessing a resurgence, with new evidence and widespread use demonstrating effectiveness in attenuating pain and improving the functionality of patients. Although further studies are warranted, our case shows a positive outcome with a minimally invasive procedure to aid in the treatment of a devastating chronic pain disorder. Future research in this area may lead to fewer medications and surgical complications.

REFERENCES

- 1.Merskey H, Bogduk N. In: Classifications of chronic pain: Description of chronic pain syndromes and definition of pain terms. Merskey H, Bogduk N, editors. Seattle: IASP Press; 1994. pp. 59–61. Report by the International Association for the Study of Pain Task Force on Taxonomy. [Google Scholar]

- 2. “Trigeminal Neuralgia Fact Sheet,” NINDS. Publication date June 2013. NIH Publication No. 13-5116.

- 3.International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalagia. 2013;33:629–808. doi: 10.1177/0333102413485658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gruccu G, Leandri M, Feliciani M, Manfredi M. Idiopathic and symptomatic trigeminal pain. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990;53:1034–42. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.53.12.1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cruccu G, Truini A. Refractory trigeminal neuralgia. Non-surgical treatment options. CNS Drugs. 2013;27:91–6. doi: 10.1007/s40263-012-0023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cruccu G, Gronseth G, Alkshe J, et al. AAN-EFNS guidelines on trigeminal neuralgia management. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15:1013–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heros RC, Heros DA, Schumacher JM, et al. Principles of Neurosurgery in Neurology Clinical Practice. Philadelphia: Butterworth Heinemann; 2004. p. 963. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leonne M, Bussone G. Pathophysiology of trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:755–64. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70133-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langley GB, Sheppeard H, Johnson M, Wigley RD. The analgesic effects of transcutaneous nerve stimulation and placebo in chronic pain patient. Rheumatol Int. 1984;4:119–23. doi: 10.1007/BF00541180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bartsch T, Falk D, Knudsen K, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the posterior hypothalamic area in intractable shortlasting unilateral neuralgiform headache with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT) Cephalalgia. 2011;31:1405–8. doi: 10.1177/0333102411409070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.May A. Hypothalamic deep-brain stimulation: Target and potential mechanism for the treatment of cluster headache. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:799–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magown P, Garcia R, Beauprie I, Mendez I. Occipital nerve stimulation for intractable occipital neuralgia: An open surgical technique. Clinical Neurosurgery. 2009;56:119–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kapural L, Mekhail N, Hayek S, Stanton-Hicks M, Malak O. Occipital nerve electrical stimulation via the midline approach and subcutaneous surgical leads for treatment of severe occipital neuralgia: A pilot study. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:171–4. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000156207.73396.8E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hord ED, Evans MS, Mueed S, Adamolekun B, Naritoku DK. The effect of vagus nerve stimulation on migraines. J Pain. 2003;4:530–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desousa DD, Hodaie M, Davis KD. Abnormal trigeminal nerve microstructure and brain white matter in idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia. Pain. 2014;155:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abejon D, Krames ES. Peripheral nerve stimulation or is it peripheral subcutaneous field stimulation; what is in a moniker? Neuromodulation. 2009;12:1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1403.2009.00192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain mechanisms: A new theory. Science. 1965;150:971–9. doi: 10.1126/science.150.3699.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lenadri M, Favale M. Diagnostic relevance of trigeminal evoked potentials following infraorbital nerve stimulation. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:244–50. doi: 10.3171/jns.1991.75.2.0244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matharu M, Bartsch T, Ward N, et al. Central neuromodulation in chronic migrainepatients with suboccipital stimulators: A PET study. Brain. 2004;127:220–30. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suriya P, Shiv PR, Mishra S, Bhatnagar S. Successful treatment of an intractable postherpetic neuralgia using peripheral nerve field stimulation. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010;27:59–62. doi: 10.1177/1049909109342089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson MD, Burchiel KJ. Peripheral stimulation for treatment of trigeminal postherpetic neuralgia and trigeminal posttraumatic neuropathic pain: A pilot study. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:135–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Slavin KV, Wess C. Trigeminal branch stimulation for intractable neuropathic pain: technical note. Neuromodulation. 2005;8:7–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1094-7159.2005.05215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slavin K, Colpan E, Munawar N, Wess C, Nersesyan H. Trigeminal and occipital peripheral nerve stimulation for craniofacial pain: A single-institution experience and review of the literature. Neurosurgical Focus. 2006;21:E5. doi: 10.3171/foc.2006.21.6.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Narouze SN, Kapural L. Supraorbital nerve electric stimulation for the treatment of intractable chronic cluster headache: A case report. Headache. 2007;47:1100–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00869.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bartsch T, Paemeleire K, Goadsby PJ. Neurostimulation approaches to primary headache disorders. Curr Opin Neurol. 2009;22:262–8. doi: 10.1097/wco.0b013e32832ae61e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burchiel KJ. Effects of electrical and mechanical stimulation on two foci of spontaneous activity which develop in primary afferent neurons after peripheral axotomy. Pain. 1984;18:249–65. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(84)90820-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goadsby PJ, Knight YE, Hoskin KL. Stimulation of the greater occipital nerve increases metabolic activity in the trigeminal nucleus caudalis and cervical dorsal horn of the cat. Pain. 1997;73:23–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(97)00074-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bartsch T, Goadsby PJ. Stimulation of the greater occipital nerve induces increased central excitability of dural afferent input. Brain. 2002;125:1496–509. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mekhail NA, Aeschbach A, Stanton-Hicks M. Cost benefit analysis of neurostimulation for chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2004;20:462–8. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200411000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turner J, Deyo R, Loeser J, Von Korff M, Fordyce W. The importance of placebo effects in pain treatment and research. JAMA. 1994;271:1609–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jasper J, Hayek S. Implanted occipital nerve stimulators. Pain Physician. 2008;1:187–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]