Abstract

Nitric oxide and various by-products including nitrite contribute to tissue injury by forming novel intermediates via redox-mediated nitration reactions. Nitration of unsaturated fatty acids generates electrophilic nitrofatty acids such as 9-nitrooleic acid (9-NO) and 10-nitrooleic acid (10-NO), which are known to initiate intracellular signaling pathways. In these studies, we characterized nitrofatty acid-induced signaling and stress protein expression in mouse keratinocytes. Treatment of keratinocytes with 5–25 μM 9-NO or 10-NO for 6 h upregulated mRNA expression of heat shock proteins (hsp) 27 and 70; primary antioxidants, heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and catalase; secondary antioxidants glutathione-S-transferase (GST) A1/2, GSTA3 and GSTA4; and Cox-2, a key enzyme in prostaglandin biosynthesis. The greatest responses were evident with HO-1, hsp27 and hsp70. In keratinocytes, 9-NO activated JNK and p38 MAP kinases. JNK inhibition suppressed 9-NO induced HO-1, hsp27 and hsp70 mRNA and protein expression, while p38 MAP kinase inhibition suppressed HO-1. In contrast, inhibition of constitutive expression of ERK1/2 suppressed only hsp70 indicating that 9-NO modulates expression of stress proteins by distinct mechanisms. 9-NO and10-NO also upregulated expression of caveolin-1, the major structural component of caveolae. Western blot analysis of caveolar membrane fractions isolated by sucrose density centrifugation revealed that HO-1, hsp27 and hsp70 were localized within caveolae following nitrofatty acid treatment of keratinocytes suggesting a link between induction of stress response proteins and caveolin-1 expression. These data indicate that nitrofatty acids are effective signaling molecules in keratinocytes. Moreover, caveolae appear to be important in the localization of stress proteins in response to nitrofatty acids.

Keywords: Nitrooleic acid, Skin, Nitric oxide, Heat shock proteins, Heme oxygenase-1, Free radicals

Introduction

It is becoming increasingly apparent that nitration products of unsaturated fatty acids represent an important class of endogenous biological mediators [1, 2]. Generated in nitric oxide-dependent oxidative reactions, several of these lipid products are electrophilic fatty acid nitroalkenes including nitrooleic acid and nitrolinoleic acid derivatives [3]. These fatty acids can react via Michael additions across carbon-carbon double bonds forming adducts with many cellular components, most notably, proteins [4]. By reacting with signaling proteins, nitrooleic acids and nitrolinoleic acids can regulate their function and control gene expression [5]. Electrophilic nitrofatty acids are formed in cells under conditions of nitrosative stress; they have been reported to inhibit expression of inflammatory genes and upregulate expression adaptive response genes, many of which are important in protecting cells against stress-induced injury and tissue damage [6]. Beneficial effects of nitrofatty acids have been described in several animal models of cardiovascular, inflammatory and metabolic diseases [7–9].

Earlier studies by our laboratory showed that mouse and human keratinocytes upregulate inducible nitric oxide synthase and generate nitric oxide in response to inflammatory mediators. We also demonstrated that nitric oxide is important in the control of wound healing [10]. Nitric oxide also controls keratinocyte proliferation [11], while in human skin, it plays a key role in regulating cellular responses in diseases states such as psoriasis [12, 13], as well as to infections, heat, ultraviolet light and wounding [14–16]. The aim of the present studies was to analyze the response of keratinocytes to the nitrofatty acids 9-nitrooleic acid (9-NO) and 10-nitrooleic acid (10-NO). We found that both nitrofatty acids upregulated expression of antioxidants and stress proteins. Moreover, some of these responses were regulated by mitogen activated protein kinases and caveolae. Coordinate regulation of expression of antioxidants and adaptive genes are likely to be important in mediating nitric oxide-induced inflammation and tissue injury.

Material and methods

Materials

Rabbit anti-heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) polyclonal antibody was from Stressgen Biotechnology (Victoria, BC, Canada). Rabbit polyclonal caveolin-1 antibody, goat polyclonal cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and heat shock protein (hsp) 27 antibodies, and rabbit polyclonal hsp70 antibody were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Rabbit polyclonal heat shock factor-1 (HSF-1), caveolin-1, p38, phospho-p38, JNK, phospho-JNK, Erk1/2, and phospho-Erk1/2 antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). HRP conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody, rabbit anti-goat secondary antibody, and the DC (Detergent Compatible) protein assay kit were purchased from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA). The Western Lightning enhanced chemiluminescence kit (ECL) was from Perkin Elmer Life Sciences (Boston, MA). NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagents were from Thermo Scientific (Rockford, IL) and SYBR Green Master Mix and other PCR reagents from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were from Invitrogen Corp. (Carlsbad, CA). PD 98059 and SP600125 were from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA). 9-NO and 10-NO were from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). SB203580, protease inhibitor cocktail containing 4-(2 aminoethyl)benzenesulfonyl fluoride, aprotinin, bestatin hydrochloride, N-(trans-epoxysuccinyl)-L-leucine 4-guanidinobutylamide, EDTA and leupeptin, methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MbCD), Tri Reagent and all other chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Cell cultures and treatments

PAM212 keratinocytes were obtained and maintained as previously described [17]. The cells were originally prepared from primary keratinocytes isolated from BALB/c mice [18]. For all experiments, cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were seeded into either 6-well plates (1 × 106 cells/well) or 10 cm plates (5 × 106 cells/plate) and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. After reaching ~90% confluence, cells were treated with vehicle control or increasing concentrations of freshly prepared 9-NO or 10-NO (5–25 μM). For protein analysis, treated cells, grown in 6-well dishes, were lysed by the addition of 300 μl SDS lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-base, pH 7.6, supplemented with 1% SDS and the protease inhibitor cocktail), transferred into 1.5 ml Eppendorf microcentrifuge tubes, sonicated on ice and then centrifuged (100 × g, 5 min at 4° C). Supernatants were then analyzed by Western blotting. Cells were prepared for mRNA analysis as previously described [19].

For kinase inhibition experiments, cells were pretreated with the p38 MAP kinase inhibitor, SB203580 (10 μM), the JNK kinase inhibitor, SP600125 (20 μM), or the ERK1/2 kinase inhibitor, PD98059 (10 μM) for 3 hr. Nitrooleic acids or vehicle control was then added to the medium. After 6 hr, the cells were removed from the plates using a scraper and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 10 min. Cells were then analyzed for mRNA and protein expression by real-time PCR and Western blotting, respectively. For analysis of cytoplasmic and nuclear expression of HSF-1, cell pellets (~20 μl packed volume) were resuspended in 200 μl ice-cold cytoplasmic extraction reagent (Thermo Scientific) in Eppendorf centrifuge vials and centrifuged for 5 min at 16,000 × g. Supernatants were immediately transferred to clean pre-chilled tubes and the nuclear fractions extracted from the pellets by adding 100 μl ice-cold nuclear extraction reagent. Samples were stored at −70°C until analysis.

Isolation of caveolae

Caveolar fractions of cells were prepared as described by Smart et al. [20]. Briefly, treated cells were washed three times with PBS, scraped into 5 ml sucrose buffer (0.25 M sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, and 20 mM Tris, pH 7.8) and centrifuged at 1400 g for 5 min. Cell pellets were then suspended in 1 ml sucrose buffer and homogenized with 20 strokes in a Dounce homogenizer. Lysates were transferred to Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged for 10 min at 1000 × g at 4°C. Supernatants were collected and the homogenization process repeated with cell pellets. After combining the supernatants, 2 ml were carefully layered on top of 8 ml of a 30% Percoll solution in sucrose buffer and centrifuged for 30 min at 84,000 × g in a Ti 70 rotor using an L7–55 Beckman ultracentrifuge (Brea, CA) to separate caveolae containing plasma membrane fractions. Fractions were collected and stored at −70°C until analysis.

Western blotting

Protein concentrations of total cell lysate, nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, and caveolae and non-caveolae fractions were quantified using the DC protein assay kit with bovine serum albumin as the standard [21]. Samples (15 μg/well) were then electrophoresed on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After blocking in 5% milk in Tris buffer at room temperature, the blots were incubated overnight at 4°C with HO-1 antibody (1:1000), hsp27 antibody (1:200), hsp70 antibody (1:400), β-actin antibody (1:3000), caveolin-1 antibody (1:1000), Cox-2 antibody (1:500), HSF-1 antibody (1:500), or MAP kinase antibodies (1:1000), washed with tTBS (Tris-buffered saline supplement with 0.1% Tween 20) and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies. After 1 hr at room temperature, proteins were visualized by ECL chemiluminescence.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from the cells using the Tri Reagent as previously described by [19]. cDNA was synthesized using M-MLV reverse transcriptase. The cDNA was diluted 1:10 in RNase-DNase-free water for PCR analysis. For each gene, a standard curve was generated from serial dilutions of cDNA mixtures of all the samples. Real-time PCR was conducted on an ABI Prism 7900 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using 96-well optical reaction plates. SYBR-Green was used for detection of the fluorescent signal and the standard curve method was used for relative quantitative analysis. The primer sequences for the genes were generated using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems) and the oligonucleotides were synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. (Coralville, IA). A mouse β-actin house-keeping gene was used to normalize all the values. The forward (5′-3′) and reverse (5′-3′) primers used are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Real-time PCR primer sequences

| Gene | Forward (5′-3′) | Reverse (5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| β-actin | TCA CCC ACA CTG TGC CCA TCT ACG A | GGA TGC CAC AGG ATT CCA TAC CCA |

| HO-1 | ACC AGG GCA TCA AAA ACT TG | GCC CTG AAG CTT TTT GTC AG |

| Cox-2 | CAT TCT TTG CCC AGC ACT TCA C | GAC CAG GCA CCA GAC CAA AGA C |

| GSTA1-2 | CAG AGT CCG GAA GAT TTG GA | CAA GGC AGT CTT GGC TTC TC |

| GSTA3 | GCA AGC CTT GCC AAG ATC AA | GGC AGG GAA GTA ACG GTT CC |

| GSTA4 | CCC TTG GTT GAA ATC GAT GG | GAG GAT GGC CCT GGT CTG T |

| Catalase | ACC AGG GCA TCA AAA ACT TG | GCC CTG AAG CTT TTT GTC AG |

| Hsp27 | AAG GAA GGC GTG GTG GAG AT | TTC GTC CTG CCT TTC TTC GT |

| Hsp70 | CAG CGA GGC TGA CAA GAA GAA | GGA GAT GAC CTC CTG GCA CT |

Statistical analysis

Data were evaluated using the two-way ANOVA. p< 0.05 was considered statistically significant

Results

Effects of nitrooleic acids on antioxidants and stress proteins

9-NO and 10-NO were found to upregulate expression of HO-1, hsp27, hsp70, Cox-2, and the glutathione-S-transferases GSTA1-2, GSTA3 and GSTA4 in a generally similar manner in the range of 5–25 μM (Table 2). HO-1 (9–55 fold) was most responsive, followed by hsp70 (5–34 fold), hsp27 (9–20 fold), and Cox-2 (5–9 fold). GSTA1-2 (3–18 fold), GSTA3 (5–19 fold) and GSTA4 (3–19 fold) also showed similar upregulation in response to the nitrooleic acids. Catalase was only induced by 10 μM and 25 μM 10-NO (4–6 fold).

Table 2.

Effects of nitrooleic acids on gene expression in mouse keratinocytes.

| 9-NO1 | 10-NO | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 μM | 10 μM | 25 μM | 5 μM | 10 μM | 25 μM | |

| HO-1 | 9.5 ± 4.2* | 54.0 ± 4.2* | 44.0 ± 4.6* | 2.5 ± 0.3* | 40.6 ± 0.2* | 77.4 ± 9.2* |

| Hsp27 | 12.3 ± 1.3* | 18.1 ± 3.3* | 9.4 ± 0.9* | 10.5± 0.8* | 18.2 ± 2.1* | 19.2 ± 4.8* |

| Hsp70 | 5.0 ± 0.5* | 6.0 ± 0.6* | 29.7 ± 4.6* | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 11.2 ± 3.1* | 33.4 ± 6.5* |

| Cox-2 | 2.7 ± 0.9 | 5.0 ± 1.2* | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 5.3 ± 1.5* | 9.4 ± 1.6* |

| Catalase | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 5.7 ± 1.2* | 4.0 ± 1.4* |

| GSTA1-2 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 14.0 ± 3.4* | 3.7 ±1.6* | 5.7 ± 0.7* | 17.9 ±1.2* | 17.9 ± 1.1* |

| GSTA 3 | 5.0 ± 0.2* | 9.6 ± 1.3* | 7.3 ± 1.1* | 5.4 ± 0.8* | 17.0 ± 3.4* | 18.3 ± 5.0* |

| GSTA 4 | 2.9 ± 0.5* | 11.2 ± 2.0* | 6.8 ± 1.7* | 4.4 ± 0.7* | 18.7 ± 4.2* | 1.7 ± 0.1 |

Keratinocytes were treated with control, 5 μM, 10 μM or 25 μM 9-NO or 10-NO for 6 hr. mRNA was isolated and analyzed for gene expression by quantitative RT-PCR. Data are presented as fold change in gene expression relative to control. Values are means ± SE (n=3).

Significantly (p< 0.05) different from control.

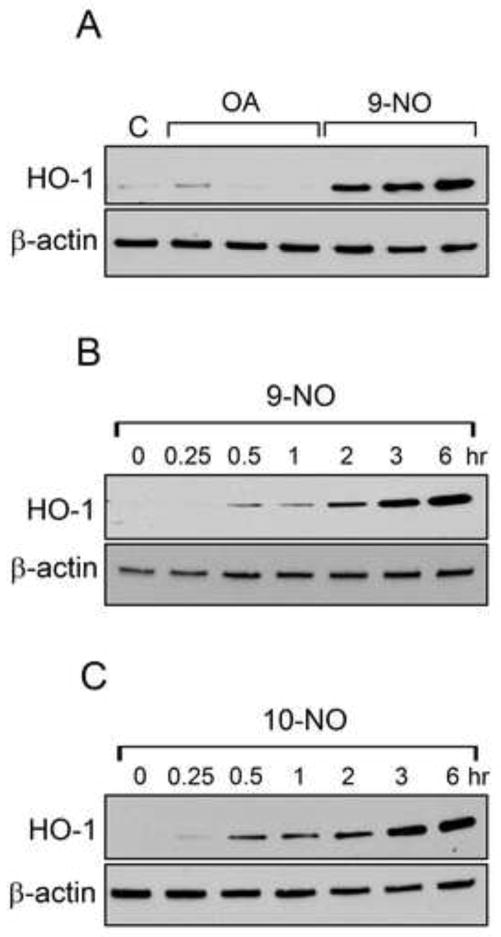

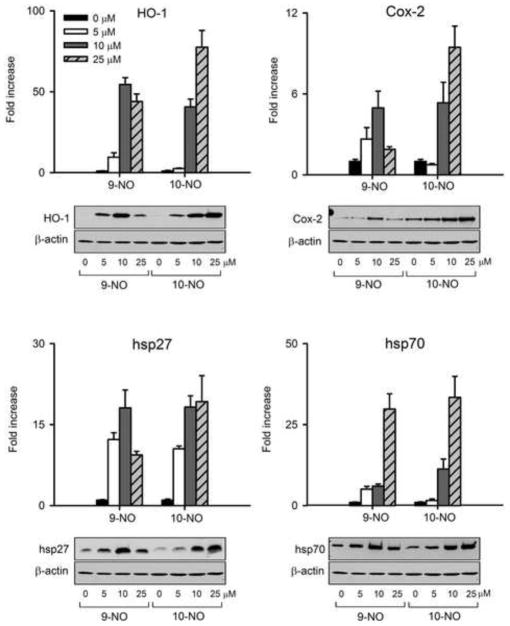

Both 9-NO and 10-NO also upregulated HO-1 protein in time- and concentration-dependent manners (Figure 1 and Figure 2, panel A); this was maximal 6 hr after treatment with 25 μM nitrooleic acids. The unmodified fatty acid, oleic acid, which cannot undergo a Michael addition, had no effect on HO-1 (Figure 1, panel A). 9-NO and 10-NO also upregulated protein expression for Cox-2, hsp27, hsp70 (Figure 2). Whereas induction of HO-1, hsp27 and hsp70 was similar for 9-NO and 10-NO, Cox-2 expression was more responsive to 10-NO.

Figure 1. Effects of nitrooleic acids on HO-1 expression.

Keratinocytes were treated with vehicle control (C), 10 μM oleic acid (OA), or 10 μM 9-NO for 6 hr (Panel A) or with control (C) or 10 μM 9-NO or 10-NO for 0–6 hr (Panels B and C, respectively). Cell lysates were prepared and analyzed for HO-1 expression by western blotting. β-actin was used as a control. One representative blot from 3 experiments is shown

Figure 2. Effects of nitrooleic acids on stress-related gene expression.

mRNA or protein was extracted from keratinocytes treated with 0, 5, 10 or 25 μM nitrooleic acids for 6 hr. Samples were then analyzed by quantitative RT-PCR (upper panels) or western blotting (lower panels) for HO-1, Cox-2, hsp27 or hsp70 gene and protein expression. Bars represent the mean +/− SE (n = 3). *Significantly different from control (P < 0.05). All increases in HO-1 and hsp27 by 9-NO and 10-NO were significant when compared to control (p < 0.05). Increases in Cox-2 were significant following treatment with 10 μM 9-NO and 10 μM and 25 μM 10-NO. Increases in hsp70 were significant at all concentrations of 9-NO and 10 μM and 25 μM 10-NO.

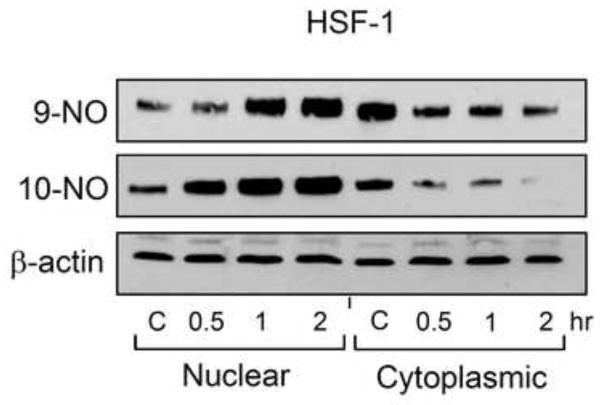

Previous work has shown that heat shock proteins and HO-1 are regulated by the transcription factor HSF-1 [22, 23]. We found that HSF-1 was largely localized in the cytoplasm of PAM212 keratinocytes. A marked increase in nuclear localization of HSF-1 was noted after treatment of the cells with 9-NO or 10-NO (Figure 3). These effects were time-dependent in the range of 0.5 ~ 2 hr.

Figure 3. Effects of nitrooleic acids on HSF-1 activation.

Cells were treated with control (C), 10 μM 9-NO, or 10 μM 10-NO for 0.5, 1 or 2 hr. Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were prepared and analyzed for HSF-1 expression by western blotting. One representative blot from 3 experiments is shown.

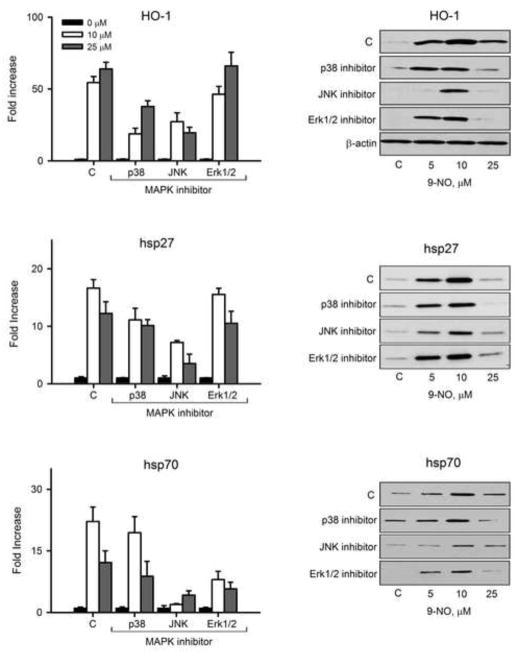

Role of MAP kinase signaling in nitrooleic acid induced expression of HO-1, hsp27 and hsp70

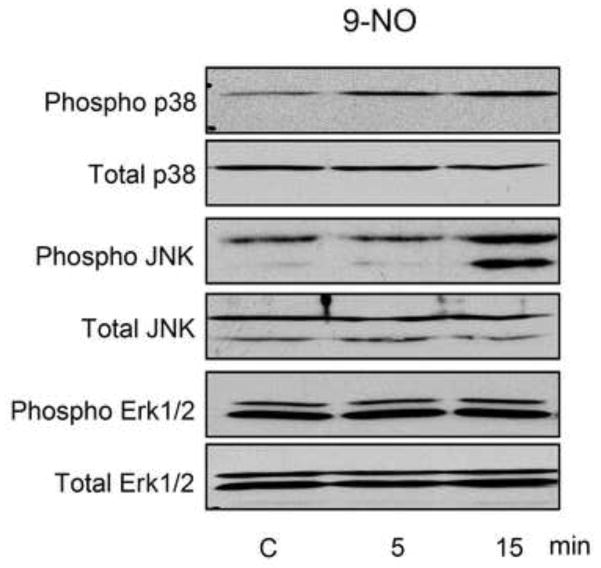

We next analyzed the effects of the nitrofatty acids on MAP kinase activation in keratinocytes. We found that 10 μM 9-NO induced p38 and JNK phosphorylation, with no effects of expression of total p38 or total JNK protein expression (Figure 4). In contrast, Erk1/2 kinase was constitutively activated in the cells and 9-NO did not change this activity. To evaluate the role of MAP kinases in induction of HO-1, hsp27 and hsp70 we used SB203580, a p38 kinase inhibitor, SP600125, a JNK inhibitor, and PD98059, an Erk1/2 inhibitor. JNK inhibition suppressed 9-NO-mediated increases in mRNA and protein expression for all three proteins, while p38 kinase inhibition only suppressed the induction of HO-1, and Erk1/2 inhibition only suppressed hsp70 (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Effects of 9-nitrooleic acid on MAP kinase activation.

Keratinocytes were treated with control (C) or 10 μM 9-NO for 5 min or 15 min. Cell lysates were prepared and analyzed for total or phosphorylated MAP kinases by western blotting. One representative blot from 3 experiments is shown.

Figure 5. Role of MAP kinase signaling in 9-NO-induced expression of HO-1 and hsp’s.

Keratinocytes were pre-incubated with inhibitors of p38 (SB203580, 10 μM), JNK (SP600125, 20 μM), or Erk1/2 (PD98059, 10 μM) for 3 hr and then with 9-NO for additional 6 hr. Cell lysates were prepared and analyzed for mRNA (left panels) or protein expression (right panels) by real time PCR and western blotting, respectively. Bars represent the mean +/− SE (n = 3). Changes in HO-1 mRNA expression were only significant with the p38 and JNK inhibitors (p < 0.05). Changes in hsp27 mRNA expression were only significant with the JNK inhibitor. Changes in mRNA expression of hsp70 were only significant with the JNK and Erk1/2 inhibitors.

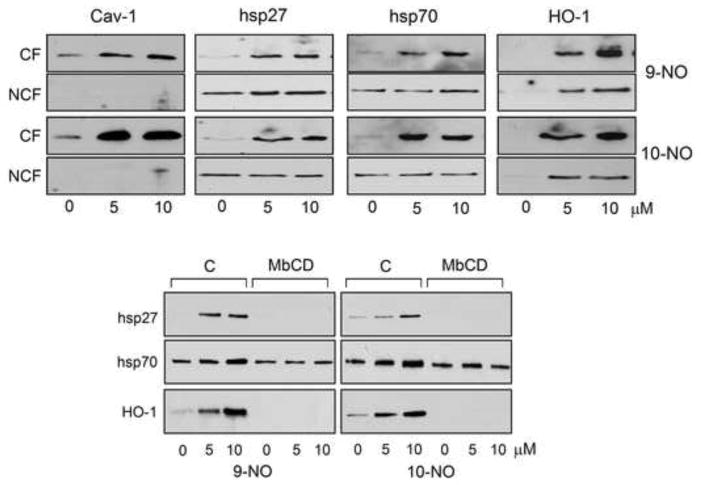

Role of caveolae in nitrooleic acid-induced protein expression

Previous studies showed that caveolae regulate expression of adaptive response genes including hsp27 and hsp70 [24]. We found that caveolar fractions, but not non-caveolar fractions, of keratinocytes contained caveolin-1, the major structural protein in caveolae (Figure 6). Interestingly, treatment of the cells with 9-NO or 10-NO increased expression of caveolin-1 (Figure 6). Constitutive levels of hsp27 and hsp70, but not HO-1, were identified in non-caveolar fractions of control keratinocytes. Treatment with 9-NO and 10-NO selectively increased expression of hsp27 and hsp70 in caveolar fractions of the cells. In contrast, HO-1 was induced by 9-NO and 10-NO in both caveolar and non-caveolar fractions of the cells. When the cells were treated with an inhibitor that disrupts caveolae (MbCD), both control and induced expression of hsp27 and HO-1 were suppressed, while only control levels of hsp70 were expressed in inhibitor-treated cells. Neither 9-NO nor 10-NO altered expression of hsp70 in MbCD-treated cells.

Figure 6. Localization of nitrooleic acid-induced proteins in caveolae.

Upper panels: Keratinocytes were treated with 0, 5 μM or 10 μM 9-NO or 10-NO. After 6 hr, caveolar fractions (CF) and non-caveolar fractions (NCF) were prepared and analyzed for protein expression by western blotting. Lower panels: Cells were pretreated with MbCD (5 mM) or control (C) for 30 min and then with nitrooleic acids. After 6 hr, total cell lysates were prepared and analyzed by western blotting. Representative blots from 3 separate experiments are shown.

Discussion

Cells adapt to stress by generating mediators that protect against injury and promote wound repair [25, 26]. It is well recognized that skin and skin-derived cells including keratinocytes can generate excessive amounts of nitric oxide following injury or in response to cytokines, processes that can lead to nitrosative stress [27]. Nitrofatty acids are known to be generated in human tissues [28, 29] following nitrosative stress. By stimulating expression of adaptive proteins and antioxidants and/or inhibiting cytokine signaling, these reactive lipids function as antiinflammatory agents [1]. Sulfhydryl residues in proteins in different cell compartments including membranes, cytoplasm, mitochondria and nucleus that regulate signal transduction are highly susceptible to modification by nitrofatty acids and mediate gene expression changes [30]. The present studies demonstrate that keratinocytes respond to nitrofatty acids by synthesizing a number of adaptive proteins that are important in protecting cells against stressors. Thus, 9-NO or 10-NO effectively induce keratinocyte expression of heat shock proteins, antioxidant enzymes, enzymes that generate antioxidants, and enzymes that detoxify reactive oxygen species (e.g., HO-1, catalase and GST’s), and Cox-2, which generates eicosanoids. These findings are consistent with a protective role of nitrofatty acids in keratinocytes.

In keratinocytes, HO-1 and catalase are upregulated by stressors that stimulate nitric oxide production including ultraviolet light, paraquat and heavy metals [19, 21, 31]. Similarly, we observed increased expression of HO-1, catalase and GST’s following nitrofatty acid stimulation of keratinocytes. HO-1 is a key cellular antioxidant and in mouse skin, its expression has been shown to accelerate wound healing [32]. Nitrofatty acids have been reported to induce HO-1 in the vasculature of mice, a process that is thought to contribute to their ability to exert antiinflammatory activity and protect against vascular injury [2, 33] and we speculate that it plays a similar role in keratinocytes. Catalase detoxifies hydrogen peroxide, effectively reducing oxidative stress. Increased expression of catalase in keratinocytes and mouse skin has been shown to protect against hydrogen peroxide-induced damage as well as UVB-induced apoptosis [34–36]. In mouse skin catalase also stimulates proliferation of keratinocytes surrounding excisional dermal wounds [37]. We also found that 9-NO and 10-NO upregulated keratinocyte GSTA1-2, GSTA3 and GSTA4. These mediate the conjugation of glutathione to oxidized cellular macromolecules, facilitating their elimination and limiting tissue injury [38, 39]. In addition, GSTA enzymes terminate lipid peroxidation chain reactions by removing hydroperoxides and aldehydes generated during oxidative stress [38, 39]. Our findings are consistent with previous work showing that oxidative stressors including paraquat and UVB light effectively up regulate these GST’s in mouse keratinocytes [19, 21]. These enzymes likely act in concert with HO-1 and catalase to limit oxidative and nitrosative stress and promote wound healing.

The nitrofatty acids were also found to upregulate keratinocyte expression of mRNA and protein for Cox-2. At present it is unclear whether this contributes to injury or repair as both pro- and antiinflammatory eicosanoids are generated via Cox-2 from prostaglandin (PG) H2 [40, 41]. Of particular interest is the antiinflammatory eicosanoid 15-deoxy Δ12,14 PGJ2 [42]. UVB light has been shown to stimulate production of PGJ2 by mouse keratinocytes [42]. It remains to be determined if antiinflammatory prostaglandins are produced in keratinocytes following nitrofatty acid treatment, and the extent to which they play a role in ameliorating skin inflammation. However, as PGE2 generated via Cox-2 is an important mediator of skin inflammation [42], one cannot exclude the possibility that nitrofatty acids also contribute to the proinflammatory activity of nitrosative stress.

Hsp’s are molecular chaperones upregulated following oxidative stress [43]. They function to protect cells against injury and facilitate the resolution of inflammation and wound healing. In the skin, hsp’s have also been shown to enhance tissue repair [44]. In previous studies, we demonstrated that hsp27 and hsp70 are rapidly induced in mouse and human keratinocytes by dermal vesicants which induce oxidative and nitrosative stress [24]. Similarly, we found that 9-NO and 10-NO effectively upregulated keratinocyte mRNA and protein for hsp27 and hsp70. Both hsp’s are important in maintaining the integrity of proteins; they also function as antioxidants, and play key roles in protecting cells against apoptosis and cell damage [45–48]. Our data are consistent with earlier studies demonstrating that nitrofatty acids can upregulate hsp’s and related proteins, providing further support for the idea that these proteins are important in protecting cells against nitrosative stress [49].

A question arises as to the mechanism by which nitrofatty acids modulate expression of antiinflammatory/adaptive response proteins in keratinocytes. Previous work from our laboratory and others has shown that expression of many of the stress related proteins are regulated, at least in part, by MAP kinase signaling [17, 50]. The present studies demonstrate that 9-NO activated JNK and p38 MAP kinases in keratinocytes. These data are in accord with reports showing increases in MAP kinase activity in response to other Michael acceptors, including 4-hydroxynonenal in lung microvascular endothelial cells and epithelial cells [51, 52]. Our findings that JNK inhibition suppressed 9-NO-induced HO-1, hsp27 and hsp70 expression provide support for a role of this MAP kinase in regulating the activity of nitrofatty acids. We also found that inhibition of p38 MAP kinase suppressed 9-NO-induced HO-1 expression, while ERK1/2 inhibition suppressed hsp70 expression. These data indicate that 9-NO regulates expression of adaptive response genes by distinct mechanisms. The intracellular signaling pathways leading to 9-NO activation of MAP kinase activity are not known. 9-NO may directly interact with the kinases to control their activity [4, 53] or it may trigger upstream signaling pathways that activate MAP kinase signaling [53].

It should be noted that additional regulatory pathways have been identified by which nitrofatty acids modulate gene expression. For example, the Nrf2/Keap-1 pathway is known to be important in mediating protection against electrophilic and oxidative stress by induction of phase 2 enzymes including the GST’s [54]. In human endothelial cells, nitrofatty acids have been reported to act via Nrf2/Keap-1 signaling, which controls expression of adaptive response genes including HO-1, NQO1 and GSH biosynthetic enzymes [33, 49, 55, 56]. Nitrofatty acids also activate hypoxia inducible factor (HIF) signaling and regulate HIF-1α target genes in human endothelial cells [57], as well as peroxisome proliferator-activating receptors [33, 58]. In contrast, nitrofatty acids inhibit LPS-induced NF-κB signaling in mouse macrophages and aorta’s, a process that may be important in controlling inflammation [7].

Another important pathway regulating expression of hsp’s is the transcription factor HSF-1. Localized in the cytoplasm under physiological conditions, HSF-1 translocates to the nucleus under conditions of stress [59]. Trimerization and phosphorylation regulates the transcription of HSF-1 sensitive genes [60]. We found that mouse keratinocytes constitutively express HSF-1 in the cytoplasm, and to a lesser extent, the nucleus. Treatment of keratinocytes with 9-NO or 10-NO reduced cytoplasmic expression of HSF-1, increasing its nuclear expression, suggesting that HSF-1 mediates, at least in part, the action of the nitrofatty acids. Cytoplasmic localization of HSF-1 is thought to be controlled by its association with hsp70 and hsp-90 [61, 62]. This is in accord with our findings of constitutive expression of hsp70 in the keratinocytes. Nitrofatty acids may function by binding to hsp70 or a related protein, a process that could cause it to dissociate from and activate HSF-1 [53]. Binding to hsp’s has been described for other electrophiles including 4-hydroxynonenal which stimulate nuclears translocation of HSF-1 [63–65]. Further studies are needed to determine the relative contributions of HSF-1, MAP kinases and other signaling molecules in controlling the expression of adaptive stress response proteins in keratinocytes.

Caveolae are specialized membrane lipid rafts that function to control a variety of biochemical signaling molecules regulating growth and differentiation [66]. Cav-1 is the major structural protein in caveolae [67]. Basal keratinocytes in mouse and human skin strongly express Cav-1 [68, 69]. Basal cell proliferation is increased in mice lacking Cav-1, along with susceptibility to carcinogens [70–72]. Cav-1 −/− mice are also more sensitive to phorbol ester-induced epidermal hyperplasia, as well as the development of papillomas in a two stage mouse skin carcinogenesis model [71]. Thus, Cav-1/caveolae play dynamic roles in regulating epidermal homeostasis and responses to environmental stimuli. Our data demonstrate that nitrofatty acids effectively induce Cav-1 protein in keratinocytes. Similar upregulation of Cav-1 has been described after treatment of keratinocytes with the vesicant, 2-chloroethyl ethyl sulfide [24]. Increased Cav-1 expression may be an important adaptive response that facilitates the sequestration of signaling molecules regulating production of inflammatory mediators. This may contribute to the antiinflammatory actions of the nitrofatty acids. Our data also show that low constitutive expression of hsp27 and hsp70 in keratinocytes is largely in non-caveolar fractions of the cells, with minimal constitutive expression of HO-1. Of note, increases in hsp27, hsp70 and HO-1 in response to nitrofatty acids were largely associated with caveolae. In this regard, earlier work has shown that cellular stressors can induce HO-1 or hsp70 expression in lipid rafts and caveolae in several cell types including mouse mesangial cells, human epithelial cells and rat endothelial cells [73–75]. The function of HO-1 and hsp’s in caveolae is unknown. Caveolae contain not only HO-1, but also other heme degrading enzymes including biliverden reductase [76]. It is possible that localization of HO-1 in caveolae is important in the generation of antioxidants that are important in protecting their structural integrity. Hsp’s function to support the folding and transport of proteins [77], which may be important in protecting caveolae from nitrosative stress. Caveolae are also known to transport hsp’s into the extracellular environment where they play a role in immune regulation [73, 78]. This may be important in controlling inflammatory reactions and protecting against stress-induced damage [78, 79]. Also of note is our finding that caveolae regulate nitrofatty acid-induced expression of stress proteins. Thus, suppression of caveolae by MbCD blocked 9-NO and 10-NO-induced increases in HO-1 and hsp’s. Similar results have been described with vesicants and heat shock [24, 74]. Based on these data, a reduction in caveolae would be expected to reduce nitrofatty acid-induced antiinflammatory activity. In this regard, increased inflammatory cell infiltration has been observed in mouse skin from Cav-1 −/− mice following treatment with a phorbol ester tumor promoter [71], which is known to induce nitrosative stress [80–82].

In summary, our data show that concentrations of nitrofatty acids that occur under physiological or pathological conditions upregulate expression of genes that are important in regulating stress-induced damage in keratinocytes. That many of these genes are important in the control of inflammation is consistent with an emerging literature indicating that these electrophilic lipids are antiinflammatory, and that their production following nitrosative stress may be important in protecting against tissue injury. Our data also adds to the understanding of the signaling pathways by which nitrofatty acids regulate gene expression. A particularly novel aspect of our work is the identification of HO-1 and hsp’s in keratinocyte caveolae, and their response to 9-NO and 10-NO. These data support the notion that caveolae are important in sequestering stress induced proteins, as well as regulating their expression. Taken together, these findings further support the idea that nitrofatty acids function as signaling molecules to regulate cellular responses to nitrosative stress.

Highlights.

Nitric oxide-dependent reactions with lipids generate electrophilic nitrooleic acids.

Electrophilic nitrooleic acids induce antioxidant proteins in mouse keratinocytes.

Induction of antioxidant proteins was regulated in part via MAP kinases and caveolae.

Nitrooleic acids are effective signaling molecules in keratinocytes.

Nitrofatty acids may be important in regulating skin inflammation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01GM034310, R01ES004738, U54AR055073, R01CA132624 and P30ES005022.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Freeman BA, Baker PR, Schopfer FJ, Woodcock SR, Napolitano A, d’Ischia M. Nitro-fatty acid formation and signaling. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:15515–15519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800004200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khoo NK, Rudolph V, Cole MP, Golin-Bisello F, Schopfer FJ, Woodcock SR, Batthyany C, Freeman BA. Activation of vascular endothelial nitric oxide synthase and heme oxygenase-1 expression by electrophilic nitro-fatty acids. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:230–239. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker PR, Lin Y, Schopfer FJ, Woodcock SR, Groeger AL, Batthyany C, Sweeney S, Long MH, Iles KE, Baker LM, Branchaud BP, Chen YE, Freeman BA. Fatty acid transduction of nitric oxide signaling: multiple nitrated unsaturated fatty acid derivatives exist in human blood and urine and serve as endogenous peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ligands. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:42464–42475. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504212200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baker LM, Baker PR, Golin-Bisello F, Schopfer FJ, Fink M, Woodcock SR, Branchaud BP, Radi R, Freeman BA. Nitro-fatty acid reaction with glutathione and cysteine. Kinetic analysis of thiol alkylation by a Michael addition reaction. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:31085–31093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704085200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iles KE, Wright MM, Cole MP, Welty NE, Ware LB, Matthay MA, Schopfer FJ, Baker PR, Agarwal A, Freeman BA. Fatty acid transduction of nitric oxide signaling: nitrolinoleic acid mediates protective effects through regulation of the ERK pathway. Free Radical Biol Med. 2009;46:866–875. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Geisler AC, Rudolph TK. Nitroalkylation - A redox sensitive signaling pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1820:777–784. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villacorta L, Chang L, Salvatore SR, Ichikawa T, Zhang J, Petrovic-Djergovic D, Jia L, Carlsen H, Schopfer FJ, Freeman BA, Chen YE. Electrophilic nitro-fatty acids inhibit vascular inflammation by disrupting LPS-dependent TLR4 signalling in lipid rafts. Cardiovasc Res. 2013;98:116–124. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rudolph V, Rudolph TK, Schopfer FJ, Bonacci G, Woodcock SR, Cole MP, Baker PR, Ramani R, Freeman BA. Endogenous generation and protective effects of nitro-fatty acids in a murine model of focal cardiac ischaemia and reperfusion. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85:155–166. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rudolph TK, Rudolph V, Edreira MM, Cole MP, Bonacci G, Schopfer FJ, Woodcock SR, Franek A, Pekarova M, Khoo NK, Hasty AH, Baldus S, Freeman BA. Nitro-fatty acids reduce atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:938–945. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.201582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heck DE, Laskin DL, Gardner CR, Laskin JD. Epidermal growth factor suppresses nitric oxide and hydrogen peroxide production by keratinocytes. Potential role for nitric oxide in the regulation of wound healing. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21277–21280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mendes DA, Horinouchi CD, Prudente Ada S, Soley Bda S, Assreuy J, Otuki MF, Cabrini DA. In vivo participation of nitric oxide in hyperproliferative epidermal phenomena in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;687:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weller R. Nitric oxide--a newly discovered chemical transmitter in human skin. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:665–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sikar Akturk A, Ozdogan HK, Bayramgurler D, Cekmen MB, Bilen N, Kiran R. Nitric oxide and malondialdehyde levels in plasma and tissue of psoriasis patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26:833–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghaffari A, Miller CC, McMullin B, Ghahary A. Potential application of gaseous nitric oxide as a topical antimicrobial agent. Nitric Oxide-Biol Ch. 2006;14:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weller R, Schwentker A, Billiar TR, Vodovotz Y. Autologous nitric oxide protects mouse and human keratinocytes from ultraviolet B radiation-induced apoptosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C1140–1148. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00462.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luo JD, Chen AF. Nitric oxide: a newly discovered function on wound healing. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2005;26:259–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2005.00058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Black AT, Joseph LB, Casillas RP, Heck DE, Gerecke DR, Sinko PJ, Laskin DL, Laskin JD. Role of MAP kinases in regulating expression of antioxidants and inflammatory mediators in mouse keratinocytes following exposure to the half mustard, 2-chloroethyl ethyl sulfide. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2010;245:352–360. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2010.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuspa SH, Hawley-Nelson P, Koehler B, Stanley JR. A survey of transformation markers in differentiating epidermal cell lines in culture. Cancer Res. 1980;40:4694–4703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Black AT, Gray JP, Shakarjian MP, Laskin DL, Heck DE, Laskin JD. Distinct effects of ultraviolet B light on antioxidant expression in undifferentiated and differentiated mouse keratinocytes. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:219–225. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smart EJ, Ying YS, Mineo C, Anderson RG. A detergent-free method for purifying caveolae membrane from tissue culture cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:10104–10108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Black AT, Gray JP, Shakarjian MP, Laskin DL, Heck DE, Laskin JD. Increased oxidative stress and antioxidant expression in mouse keratinocytes following exposure to paraquat. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;231:384–392. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu C. Heat shock transcription factors: structure and regulation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1995;11:441–469. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.11.110195.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koizumi S, Gong PF, Suzuki K, Murata M. Cadmium-responsive element of the human heme oxygenase-1 gene mediates heat shock factor 1-dependent transcriptional activation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8715–8723. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609427200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Black AT, Hayden PJ, Casillas RP, Heck DE, Gerecke DR, Sinko PJ, Laskin DL, Laskin JD. Regulation of Hsp27 and Hsp70 expression in human and mouse skin construct models by caveolae following exposure to the model sulfur mustard vesicant, 2-chloroethyl ethyl sulfide. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2011;253:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eming SA, Krieg T, Davidson JM. Inflammation in wound repair: molecular and cellular mechanisms. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:514–525. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landriscina M, Maddalena F, Laudiero G, Esposito F. Adaptation to oxidative stress, chemoresistance, and cell survival. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:2701–2716. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weller R. Nitric oxide: a key mediator in cutaneous physiology. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:511–514. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2003.01365.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsikas D, Zoerner AA, Mitschke A, Gutzki FM. Nitro-fatty acids occur in human plasma in the picomolar range: a targeted nitro-lipidomics GC-MS/MS study. Lipids. 2009;44:855–865. doi: 10.1007/s11745-009-3332-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salvatore SR, Vitturi DA, Baker PR, Bonacci G, Koenitzer JR, Woodcock SR, Freeman BA, Schopfer FJ. Characterization and quantification of endogenous fatty acid nitroalkene metabolites in human urine. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:1998–2009. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M037804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Groeger AL, Freeman BA. Signaling actions of electrophiles: anti-inflammatory therapeutic candidates. Mol Interv. 2010;10:39–50. doi: 10.1124/mi.10.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Applegate LA, Luscher P, Tyrrell RM. Induction of heme oxygenase: a general response to oxidant stress in cultured mammalian cells. Cancer Res. 1991;51:974–978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grochot-Przeczek A, Lach R, Mis J, Skrzypek K, Gozdecka M, Sroczynska P, Dubiel M, Rutkowski A, Kozakowska M, Zagorska A, Walczynski J, Was H, Kotlinowski J, Drukala J, Kurowski K, Kieda C, Herault Y, Dulak J, Jozkowicz A. Heme oxygenase-1 accelerates cutaneous wound healing in mice. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5803. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Khoo NK, Freeman BA. Electrophilic nitro-fatty acids: anti-inflammatory mediators in the vascular compartment. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shim JH, Cho KJ, Lee KA, Kim SH, Myung PK, Choe YK, Yoon DY. E7-expressing HaCaT keratinocyte cells are resistant to oxidative stress-induced cell death via the induction of catalase. Proteomics. 2005;5:2112–2122. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rezvani HR, Mazurier F, Cario-Andre M, Pain C, Ged C, Taieb A, de Verneuil H. Protective effects of catalase overexpression on UVB-induced apoptosis in normal human keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17999–18007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600536200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen X, Liang H, Van Remmen H, Vijg J, Richardson A. Catalase transgenic mice: characterization and sensitivity to oxidative stress. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;422:197–210. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roy S, Khanna S, Nallu K, Hunt TK, Sen CK. Dermal wound healing is subject to redox control. Mol Ther. 2006;13:211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.07.684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hayes JD, McLellan LI. Glutathione and glutathione-dependent enzymes represent a coordinately regulated defence against oxidative stress. Free Radic Res. 1999;31:273–300. doi: 10.1080/10715769900300851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang Y, Sharma R, Zimniak P, Awasthi YC. Role of alpha class glutathione S-transferases as antioxidant enzymes in rodent tissues. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2002;182:105–115. doi: 10.1006/taap.2002.9450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Morita I. Distinct functions of COX-1 and COX-2. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2002;68–69:165–175. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(02)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen C. LIPIDS COX-2’s new role in inflammation. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:401–402. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Black AT, Gray JP, Shakarjian MP, Mishin V, Laskin DL, Heck DE, Laskin JD. UVB light upregulates prostaglandin synthases and prostaglandin receptors in mouse keratinocytes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;232:14–24. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kalmar B, Greensmith L. Induction of heat shock proteins for protection against oxidative stress. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009;61:310–318. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laplante AF, Moulin V, Auger FA, Landry J, Li H, Morrow G, Tanguay RM, Germain L. Expression of heat shock proteins in mouse skin during wound healing. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:1291–1301. doi: 10.1177/002215549804601109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Charette SJ, Landry J. The interaction of HSP27 with Daxx identifies a potential regulatory role of HSP27 in Fas-induced apoptosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;926:126–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mosser DD, Caron AW, Bourget L, Meriin AB, Sherman MY, Morimoto RI, Massie B. The chaperone function of hsp70 is required for protection against stress-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7146–7159. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.19.7146-7159.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arya R, Mallik M, Lakhotia SC. Heat shock genes - integrating cell survival and death. J Biosci. 2007;32:595–610. doi: 10.1007/s12038-007-0059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vidyasagar A, Wilson NA, Djamali A. Heat shock protein 27 (HSP27): biomarker of disease and therapeutic target. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2012;5:7. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-5-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kansanen E, Jyrkkanen HK, Volger OL, Leinonen H, Kivela AM, Hakkinen SK, Woodcock SR, Schopfer FJ, Horrevoets AJ, Yla-Herttuala S, Freeman BA, Levonen AL. Nrf2-dependent and -independent responses to nitro-fatty acids in human endothelial cells: identification of heat shock response as the major pathway activated by nitro-oleic acid. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:33233–33241. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.064873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cui Y, Kim DS, Park SH, Yoon JA, Kim SK, Kwon SB, Park KC. Involvement of ERK AND p38 MAP kinase in AAPH-induced COX-2 expression in HaCaT cells. Chem Phys Lipids. 2004;129:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Usatyuk PV, Natarajan V. Role of mitogen-activated protein kinases in 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal-induced actin remodeling and barrier function in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:11789–11797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311184200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Iles KE, Dickinson DA, Wigley AF, Welty NE, Blank V, Forman HJ. HNE increases HO-1 through activation of the ERK pathway in pulmonary epithelial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2005;39:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schopfer FJ, Cipollina C, Freeman BA. Formation and signaling actions of electrophilic lipids. Chem Rev. 2011;111:5997–6021. doi: 10.1021/cr200131e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Holtzclaw WD, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Talalay P. Protection against electrophile and oxidative stress by induction of phase 2 genes: the quest for the elusive sensor that responds to inducers. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2004;44:335–367. doi: 10.1016/j.advenzreg.2003.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Villacorta L, Zhang J, Garcia-Barrio MT, Chen XL, Freeman BA, Chen YE, Cui T. Nitro-linoleic acid inhibits vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation via the Keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293:H770–776. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00261.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kansanen E, Jyrkkanen HK, Levonen AL. Activation of stress signaling pathways by electrophilic oxidized and nitrated lipids. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52:973–982. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rudnicki M, Faine LA, Dehne N, Namgaladze D, Ferderbar S, Weinlich R, Amarante-Mendes GP, Yan CY, Krieger JE, Brune B, Abdalla DS. Hypoxia inducible factor-dependent regulation of angiogenesis by nitro-fatty acids. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1360–1367. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.224626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schopfer FJ, Lin Y, Baker PR, Cui T, Garcia-Barrio M, Zhang J, Chen K, Chen YE, Freeman BA. Nitrolinoleic acid: an endogenous peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2340–2345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408384102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Anckar J, Sistonen L. Regulation of HSF1 function in the heat stress response: implications in aging and disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2011;80:1089–1115. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060809-095203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu PC, Thiele DJ. Modulation of human heat shock factor trimerization by the linker domain. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17219–17225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.17219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abravaya K, Myers MP, Murphy SP, Morimoto RI. The human heat shock protein hsp70 interacts with HSF, the transcription factor that regulates heat shock gene expression. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1153–1164. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.7.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zou J, Guo Y, Guettouche T, Smith DF, Voellmy R. Repression of heat shock transcription factor HSF1 activation by HSP90 (HSP90 complex) that forms a stress-sensitive complex with HSF1. Cell. 1998;94:471–480. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81588-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Carbone DL, Doorn JA, Kiebler Z, Sampey BP, Petersen DR. Inhibition of Hsp72-mediated protein refolding by 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Chem Res Toxicol. 2004;17:1459–1467. doi: 10.1021/tx049838g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carbone DL, Doorn JA, Kiebler Z, Ickes BR, Petersen DR. Modification of heat shock protein 90 by 4-hydroxynonenal in a rat model of chronic alcoholic liver disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:8–15. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.088088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Connor RE, Marnett LJ, Liebler DC. Protein-selective capture to analyze electrophile adduction of hsp90 by 4-hydroxynonenal. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24:1275–1282. doi: 10.1021/tx200157t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cohen AW, Hnasko R, Schubert W, Lisanti MP. Role of caveolae and caveolins in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:1341–1379. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00046.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stan RV. Structure of caveolae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1746:334–348. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sando GN, Zhu H, Weis JM, Richman JT, Wertz PW, Madison KC. Caveolin expression and localization in human keratinocytes suggest a role in lamellar granule biogenesis. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:531–541. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gassmann MG, Werner S. Caveolin-1 and-2 expression is differentially regulated in cultured keratinocytes and within the regenerating epidermis of cutaneous wounds. Exp Cell Res. 2000;258:23–32. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Capozza F, Williams TM, Schubert W, McClain S, Bouzahzah B, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Absence of caveolin-1 sensitizes mouse skin to carcinogen-induced epidermal hyperplasia and tumor formation. Am J Pathol. 2003;162:2029–2039. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64335-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Trimmer C, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP, Capozza F. Cav1 inhibits benign skin tumor development in a two-stage carcinogenesis model by suppressing epidermal proliferation. Am J Transl Res. 2013;5:80–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Razani B, Engelman JA, Wang XB, Schubert W, Zhang XL, Marks CB, Macaluso F, Russell RG, Li M, Pestell RG, Di Vizio D, Hou H, Jr, Kneitz B, Lagaud G, Christ GJ, Edelmann W, Lisanti MP. Caveolin-1 null mice are viable but show evidence of hyperproliferative and vascular abnormalities. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:38121–38138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105408200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Broquet AH, Thomas G, Masliah J, Trugnan G, Bachelet M. Expression of the molecular chaperone Hsp70 in detergent-resistant microdomains correlates with its membrane delivery and release. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21601–21606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302326200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen S, Bawa D, Besshoh S, Gurd JW, Brown IR. Association of heat shock proteins and neuronal membrane components with lipid rafts from the rat brain. J Neurosci Res. 2005;81:522–529. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lancaster GI, Febbraio MA. Exosome-dependent trafficking of HSP70: a novel secretory pathway for cellular stress proteins. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23349–23355. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim HP, Wang X, Galbiati F, Ryter SW, Choi AM. Caveolae compartmentalization of heme oxygenase-1 in endothelial cells. FASEB J. 2004;18:1080–1089. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1391com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hendrick JP, Hartl FU. Molecular chaperone functions of heat-shock proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:349–384. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.002025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Radons J, Multhoff G. Immunostimulatory functions of membrane-bound and exported heat shock protein 70. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2005;11:17–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Multhoff G. Heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70): membrane location, export and immunological relevance. Methods. 2007;43:229–237. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Robertson FM, Long BW, Tober KL, Ross MS, Oberyszyn TM. Gene expression and cellular sources of inducible nitric oxide synthase during tumor promotion. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:2053–2059. doi: 10.1093/carcin/17.9.2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lee CH, Wu SB, Hong CH, Yu HS, Wei YH. Molecular Mechanisms of UV-Induced Apoptosis and Its Effects on Skin Residential Cells: The Implication in UV-Based Phototherapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:6414–6435. doi: 10.3390/ijms14036414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ahmad N, Srivastava RC, Agarwal R, Mukhtar H. Nitric oxide synthase and skin tumor promotion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;232:328–331. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]