Abstract

Background

Studies show great variability in the prevalence of hyperopia among children. This study aimed to synthesize the existing knowledge about hyperopia prevalence and its associated factors in school children and to explore the reasons for this variability.

Methods

This systematic review followed PRISMA guidelines. Searching several international databases, the review included population- or school-based studies assessing hyperopia through cycloplegic autorefraction or cycloplegic retinoscopy. Meta-analysis of hyperopia prevalence was performed following MOOSE guidelines and using the random effects model.

Results

The review included 40 cross-sectional studies. The prevalence of hyperopia ranged from 8.4% at age six, 2-3% from 9 to 14 years and approximately 1% at 15 years. With regard to associated factors, age has an inverse association with hyperopia. The frequency of hyperopia is higher among White children and those who live in rural areas. There is no consensus about the association between hyperopia and gender, family income and parental schooling.

Conclusion

Future studies should use standardized methods to classify hyperopia and sufficient sample size when evaluating age-specific prevalence. Furthermore, it is necessary to deepen the understanding about the interactions among hyperopic refractive error and accommodative and binocular functions as a way of identifying groups of hyperopic children at risk of developing visual, academic and even cognitive function sequelae.

Keywords: Children, Cross-Sectional Studies, Hyperopia, Longitudinal Studies, Prevalence

Background

Hyperopia in childhood, particularly when severe and/or associated with accommodative and binocular dysfunctions, may be a precursor of visual motor and sensory sequelae such as accommodative esotropia, anisometropia and unilateral or bilateral amblyopia [1, 2]. Children with hyperopia may also present symptoms related to asthenopia while reading.

Studies have also shown that axial length (AL) of the eye or the relation between AL and corneal curvature (CC) radius plays an important role in the variability of hyperopic spherical equivalent refraction (SE) [3–8]. Utermen observed that after logistic regression, the combination of AL and CC contributed to explaining 60.9% of variability in hyperopic SE among children aged 3 to 14 years on average [5].

Although there are several studies on hyperopia, so far there has been no systematic review of the subject. This systematic review aims to synthesize existing knowledge about the hyperopia prevalence and associated factors among children, followed by a meta-analysis of hyperopia prevalence. This synthesis may help in the design of appropriate public policies to correct hyperopia in children.

Methods

Systematic review

The literature search was performed on MEDLINE (PubMed), Scielo, Bireme, Embase, Cochrane Library, Clinical Trials registration website and WHO databases. The following descriptors were used: refractive errors, hyperopia, prevalence and children, limited to keywords or words in the title or abstract, in either their isolated or combined form. The searches were limited to the 0-18 age range.

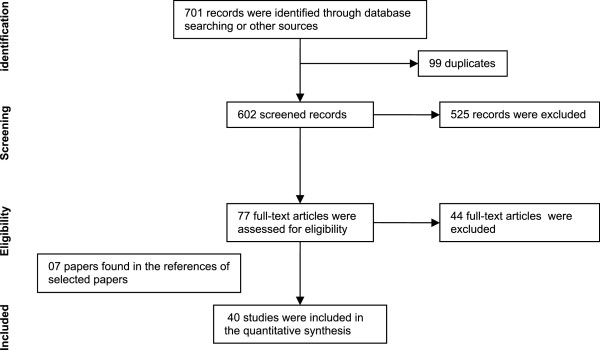

A total of 701 records were identified and screened (including theses, journals, articles, books, book chapters and institutional reports) relating to hyperopia prevalence in children up to 18 years old. 99 of these articles were duplicated. Population-based or school-based studies assessing hyperopia through cycloplegic autorefraction or cycloplegic retinoscopy were included. 525 papers were excluded owing to their focus on: specific populations as well as publications about refractive errors in subjects with eye diseases (amblyopia, strabismus, glaucoma, corneal abnormalities, chromatic aberrations, accommodative and binocular dysfunction and asthenopia); other specific clinical diseases or conditions (intellectual disability, cerebral palsy, dyslexia and prematurity); ophthalmology/optometry outpatients; genetic and/or congenital alterations; before and/or after examinations, clinical and/or surgical treatment; cost-benefit research and geographically isolated populations. A further 44 articles were excluded due to: non-random sample of the general population and schools; determination of refractive error without cycloplegia; cycloplegia only in children with low vision; hyperopia based only on visual acuity testing, studies without specific cut-off for hyperopia, samples excluding children that were already in eye care treatment, samples based on records of clinics or mobile clinics, very small and stratified samples. 07 papers found in the references of the selected articles were included (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow of information through the different phases of the systematic review.

Meta-analysis

Meta-analysis was undertaken regarding prevalence of moderate hyperopia at specific ages in 6 to 15 year-olds. Out of a total of 21 articles on hyperopia prevalence at specific ages (Table 1), three had losses of more than 20% and six did not report their response rates. Fotouhi’s study showed prevalence estimates significantly different to all the other studies in various age groups, and its inclusion in the meta-analysis resulted in a statistically significant heterogeneity test (p < 0.05). Based on the heterogeneity assumption for the effect summary, Fotouhi’s study was characterized as an outlier and excluded from the meta-analysis. Following this, the heterogeneity test produced a p-value > 0.1 in all specific ages [9]. Thus the meta-analysis was based on 11 studies assessing moderate hyperopia taking ≥ +2.00D as the cut-off point and a response rate greater than 80% (Table 1).

Table 1.

Hyperopia prevalence among children in the analyzed studies

| Author (Year) | N | Age range | Hyperopia definition | Response Rate (%) | Prevalence (%) | 95% CI | Age specific prevalence (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | |||||||

| SE | |||||||

| Zhao (2000) [10] | 5884 | 5-15 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | 95.9 | 2.7 | Not available | Males: |

| RESC | 5 years: 8.8% (2.4 – 15.2) | ||||||

| Shunyi District, China | ca | 15 years: less than 2% | |||||

| Females: | |||||||

| 5years: 19.6% (8.1 – 31.0) | |||||||

| 15 years: less than 2% | |||||||

| He (2004) [11] | 4364 | 5-15 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | 86.4 | 4.6 | 4.4 – 4.9 | 5 years: 17.0% (12.8 – 21.3) |

| RESC | 6 years: 10.7% ( 6.4 – 15.1) | ||||||

| Guangzhou, China | ca | 7 years: 4.0% (1.3 – 6.7) | |||||

| 8 years: 7.1% (3.9 – 10.4) | |||||||

| 9 years: 3.8 % (2.0 – 5.6) | |||||||

| 10 years: 4.6% (2.1 – 7.1) | |||||||

| 11 years: 3.5% (1.7 – 5.6) | |||||||

| 12 years: 2.0% (0.5 – 3.6) | |||||||

| 13 years: 3.4 % (1.6 – 5.2) | |||||||

| 14 years: 1.2% (0.3 – 2.1) | |||||||

| 15 years: 0.5% (0.0 – 1.3) | |||||||

| Fan (2004) [12] | 7560 | 5-16 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | Not stated | 4.0 | Not available | Not available |

| Right eye | |||||||

| ca | |||||||

| Hong Koong, China | |||||||

| Zhan (2000) [13] | Xiamen city: 132 | 6-7 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | Not stated | Xiamen city: 3.0 | 0.8 – 7.8 | Not available |

| Xiamen | Right eye | Xiamen countryside: 1.9 | 1.4 – 2.3 | ||||

| ca | Singapore: 2.7 | 0.8 – 6.9 | |||||

| Xiamen city, Xiamen Countryside and Singapore, China | countryside: 104 | ||||||

| Singapore: 146 | |||||||

| Pi (2010) [14] | 3070 | 6-15 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | 88.50 | 3.26 | 2.6 – 3.9 | 6 years: 9.21% (5.5 – 12.9) |

| Yong Chuan District, Western China | At last one eye was hyperopic | 7 years: 7.7% (4.7 – 10.6) | |||||

| 8 years: 5.3% (2.9 – 7.7) | |||||||

| cr | 9 years 3.1% (1.3 – 4.9) | ||||||

| 10 years: 3.5% (1.6 – 5.5) | |||||||

| 11 years: 1.2% (0.0 – 2.5) | |||||||

| 12 years: 0.7% (0.0 – 1.6) | |||||||

| 13 years: 0.3% (0.0 – 1.0) | |||||||

| 14 years: 1.1% (0.0 – 2.2) | |||||||

| 15 years: 0.9% (0.0 – 2.1) | |||||||

| He (2007) [15] | 2454 | 12-18 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | 97.6 | 1.20 | 0.8 – 1.6 | 13 years: 0.9% (0.1 – 3.1) |

| RESC | 14 years: 1.5 % (0.5 – 2.5) | ||||||

| ca | 15 years: 1.3 % (0.5 – 2.2) | ||||||

| Yangxi County, China | 16 years: 1.0% (0.3 – 2.5) | ||||||

| 17 years: 0.0 | |||||||

| Saw (2006) [16] | Malaysia: | 7-9 years | ≥ +2.00D | 83.3 | Malaysia:2.9 | 1.9 – 3.8 | Malaysia (N = 1752) |

| 7 years: 5.0% (3.0 – 7.0) | |||||||

| 8 years: 2.0% (0.7 – 3.3) | |||||||

| Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia | 1752 | RESC | Singapore: 1.7 | 1.2 – 2.4 | 9 years: 1.6% (0.4 – 2.8) | ||

| Singapore | Singapore:1962 | ca | Singapore (N = 1962) | ||||

| 7 years: 2.1% (1.3 – 3.3) | |||||||

| 8 years: 1.9% (1.0 – 3.3) | |||||||

| 9 years: 0.8% (0.2 – 2.1) | |||||||

| Goh (2005) [17] | 4634 | 7-15 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | 83.8 | 1.6 | 1.1 – 2.1 | 7 years: 5.0% (3.0 – 7.0) |

| RESC | 8 years: 2.0% (0.7 – 3.3) | ||||||

| ca | 9 years: 1.6% (0.4 – 2.8) | ||||||

| 10 years: 1.4 % (0.1 – 2.6) | |||||||

| 11 years: 0.9 % (0.0 – 2.6) | |||||||

| Gombak District, Malaysia | 12 years: 0.6% (0.0 – 1.2) | ||||||

| 13 years: 0.5% (0.0 – 1.1) | |||||||

| 14 years: 0.0 | |||||||

| 15 years: 0.9% (0.0 – 1.9) | |||||||

| Pokharel (2000) [18] | 5067 | 5-15 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | Not stated | 2.1 | Not available | Not available |

| RESC | |||||||

| ca | |||||||

| Mechi Zone, Nepal | |||||||

| Gao (2012) [19] | 5527 | 12-14 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | 89.8 | Urban: 1.4 | 0.1– 1.7 | Urban: |

| At last one eye was hyperopic | Rural: 0.4 | 0.2 – 0.6 | 12 years: 0.7% (0.4 – 1.0) | ||||

| 13 years: 0.7% (0.4 – 0.9) | |||||||

| Phnom Penhn and Kandal Provinces, Cambodia | cr | 14 years: 0.8% (0.3 – 1.3) | |||||

| Casson (2012) [20] | 2899 | 6-11 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | 87.0 | 2.8 | 1.9 – 3.7 | 6 years: 3.1% (1.7 – 5.1) |

| RESC | 11years: 1.1% (0.3 – 2.9) | ||||||

| cr | |||||||

| Vientiane Province, Lao PDR | |||||||

| Murthy (2002) [21] | 6447 | 5-15 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | 92 | 7.4 | 6.0 – 8.8 | 5 years: 15.6 % (11.0 – 20.2) |

| RESC | |||||||

| cr | |||||||

| New Delhi, India | 6 years: 13.0% (9.1 – 16.8) | ||||||

| 7 years: 10.7% (7.0 – 14.2) | |||||||

| 8 years: 8.5% (5.9 – 11.2) | |||||||

| 9 years: 6.6% (3.7 – 9.5) | |||||||

| 10 years: 5.2% (2.4 – 8.1) | |||||||

| 11 years: 7.8% (4.7 – 10.8) | |||||||

| 12 years: 5.0% (3.5 – 6.5) | |||||||

| 13 years: 3.3% (1.7 – 4.9) | |||||||

| 14 years: 4.4% (2.4 – 6.5) | |||||||

| 15 years: 3.9% (2.1 – 5.7) | |||||||

| Dandona (2002) [22] Mahabubnagar, Andhra Pradesh, India | 4074 | 7-15 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | 92.3 | 0.68 | 0.4 – 1.0 | Rural: |

| At last one eye was hyperopic | 7 years: 0.7% (0.0 – 1.2) | ||||||

| 8 years: 0.3% (0.0 – 0.8) | |||||||

| 9 years: 0.4% (0.0 – 1.0) | |||||||

| cr | 10 years: 1.2% (0.1 – 2.3) | ||||||

| 11 years: 1.6% (0.4 – 2.8) | |||||||

| 12 years: 0.8% (0.0 – 1.5) | |||||||

| 13 years: 0.6% (0.0 – 1.4) | |||||||

| 14 years: 0.3% (0.0 – 1.1) | |||||||

| 15 years: 1.1% (0.0 – 2.6) | |||||||

| Uzma (2009) [23] | Urban: 1789 | 7-15 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | Not stated | Urban: 3.3 | 1.8 – 4.8 | Urban: |

| Hyderabad, India | Rural: 1525 | At last one eye was hyperopic | Rural: 3.1 | 1.7 – 4.5 | 7 years: 4.6% (2.6 – 6.6) | ||

| ca | 8 years: 2.0% (0.4 – 3.6) | ||||||

| 9 years: 1.7% (0.8 – 2.6) | |||||||

| 10 years: 1.3% (0.5 – 2.1) | |||||||

| 11 years: 2.2% (0.9 – 3.1) | |||||||

| 12 years: 0.4% (0.0 – 0.8) | |||||||

| 13 years: 0.2% (0.0 – 0.4) | |||||||

| 14 years: 0.0 | |||||||

| 15 years: 0.4% (0.0 – 0.8) | |||||||

| Rural: | |||||||

| 7 years: 9.8% (6.6 – 13.0) | |||||||

| 8 years: 8.1% (5.4 – 10.8) | |||||||

| 9 years: 7.3% ( 3.7 – 10.9) | |||||||

| 10 years: 4.1% (2.1 – 6.1) | |||||||

| 11 years: 3.2% (1.9 – 4.5) | |||||||

| 12 years: 3.2% (1.6 – 4.8) | |||||||

| 13 years: 2.4% (0.9 – 3.9) | |||||||

| 14 years: 0.0 | |||||||

| 15 years: 0.0 | |||||||

| Fotouhi (2007) [9] | 3673 | 7-15 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | 96.8 | 16.6 | 13.6 – 19.7 | 7 years: 28.9% (22.6 – 35.2) |

| Dezful, Iran | RESC | 8 years: 22.7% (16.4 – 28.9) | |||||

| ca | 9 years: 16.7% (12.0 – 21.4) | ||||||

| 10 years: 12.4% (7.9 – 17.0) | |||||||

| 11 years: 12.9% ( 8.3 – 17.5) | |||||||

| 12 years: 16.9% (12.3 – 21.5) | |||||||

| 13 years: 14.1% (10.6 – 17.6) | |||||||

| 14 years: 13.0% (9.8 – 16.1) | |||||||

| 15 years: 10.3% (1.5 – 19.1) | |||||||

| Hashemi (2010) [24] | 345 | 5-10 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | Not stated | 10 | Not available | Not available |

| Tehran, Iran | Right eye | ||||||

| ca | |||||||

| Ostadimoghaddam (2011) [25] Mashhad, Iran | 639 | 5-15 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | Not stated | 19.05 | 15.7 – 22.4 | Not available |

| At last one eye was hyperopic | |||||||

| ca | |||||||

| Rezvan (2012) [26] | 1551 | 6-17 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | 76.8 | 5.4 | 4.3 – 6.5 | 8 years: 6.8% (2.7–11.0) |

| Bojnourd, Iran | RESC | 9 years 8.2% (3.9–12.5) | |||||

| ca | 10 years: 8.3% (4.1–12.6) | ||||||

| 11 years: 5.6 % (2.0–9.2) | |||||||

| 12 years: 3.8% (1.3–6.2) | |||||||

| 13 years: 2.3% (0.3–4.3) | |||||||

| 14 years: 2.5% (0.3–4.6) | |||||||

| Yekta (2010) [27] | 2130 | 7-15 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | 87.88 | 5.04 | 3.5 – 6.6 | 7 years: 8.9% (6.1 – 11.8) |

| Shiraz, Iran | RESC | 8 years: 7.7% (1.9 – 13.5) | |||||

| ca | 9 years: 4.8% (1.6 – 8.1) | ||||||

| 10 years: 7.0% (2.8 – 11.1) | |||||||

| 11 years: 2.1% (0.7 – 5.8) | |||||||

| 12 years: 3.0% (1.2 – 4.8) | |||||||

| 13 years: 2.2% (0.6 – 3.8) | |||||||

| 14 years: 5.9% (0.1 – 11.8) | |||||||

| 15 years: 0.0 | |||||||

| Robaei (2005) [28] | 1765 | 6 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | Not stated | 9.8 | Not available | - |

| Right eye | |||||||

| ca | |||||||

| SMS, Sydney, Australia | |||||||

| Ip (2008) [29] | 4094 | 6 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | Not stated | - | - | 6 years: 13.0% (9.1 – 16.8) |

| SMS, Sydney, Australia | 12 years | Eye with greater refractive error | 12 years: 5.0% (3.5 – 6.5) | ||||

| ca | |||||||

| Ip (2008) [30] | 2353 | 11-15 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | Not stated | 3.5 | 2.8 – 4.1 | Not available |

| SMS, Sydney, Australia | Both eyes | ||||||

| ca | |||||||

| Robaei (2006) [31] | 2353 | 12 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | 75.3 | 5 | Not available | Not available |

| Both eyes | |||||||

| ca | |||||||

| SMS, Sydney, Australia | |||||||

| Grönlund (2006) [32] | 143 | 4-15 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | Not stated | 9.1md | Not available | Not available |

| At last one eye was hyperopic | |||||||

| Gothenburg, Sweden | ca | ||||||

| Laatikainen (1980) [33] Uusimaa County, Finland | 822 | 7-15 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | Not stated | 9.7 | Not available | 7 – 8 years: 19.1% (13.0 – 25.1) |

| Right eye | |||||||

| cr | 9 – 10 years: 6.9% (3.5 – 10.3) | ||||||

| 11 – 12 years: 11.7% (7.5 – 15.9) | |||||||

| 14 – 15 years: 3.6% (1.1 – 6.1) | |||||||

| O’Donoghue (2012) [34] Northern Ireland (NICER) | 1053 | 6-7 years | ≥ +2.00D | 62.0 in children 6–7 years 65.0 in children 12–13 years | 26 | 20 – 33 | 6-7 years: 26% (20–33) |

| 14,7 | 9.9 – 19.4 | 12-13 years: 14.7% (9.9 – 19.4) | |||||

| 12-13 years | RESC | ||||||

| ca | |||||||

| Logan (2011) [35] Birmingham, England (AES) | 596 | 6-7 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | Not stated | 12.3 | 8.8–15.7 | Not available |

| 5.4 | 2.8 – 8.0 | ||||||

| 12-13 years | Either/both eyes | ||||||

| ca | |||||||

| Naidoo (2003) [36] | 4890 | 5-15 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | 87.3 | 2.6 | Not available | 5 years: 2.7% (0.6 – 4.8) |

| RESC | |||||||

| ca | |||||||

| Durban area, South Africa | 6 years: 2.4% (0.7 – 4.1) | ||||||

| 7 years: 2.8% (0.9 – 4.7) | |||||||

| 8 years: 1.3% (0.1 – 2.6) | |||||||

| 9 years 2.9% (0.1 – 5.7) | |||||||

| 10 years: 3.4% (1.8 – 4.9) | |||||||

| 11 years: 3.5% (1.9 – 5.1) | |||||||

| 12 years: 3.2% (1.2 – 5.1) | |||||||

| 13 years: 2.9% (0.3 – 5.5) | |||||||

| 14 years: 1.9% (0.6 – 3.2) | |||||||

| 15 years: 0.7% (0.0 – 1.8) | |||||||

| Maul (2000) [37] | 5303 | 5-15 years | ≥ + 2.00 D | 75.8 | 19.3 | Not available | Males: |

| RESC | 5 years: 22.7% (18.0 – 27.4) | ||||||

| ca | 15 years: 7.1% (3.5 – 10.6) | ||||||

| Females: | |||||||

| 5years: 26.3% (22.0 – 30.6) | |||||||

| 15 years: 8.9% (3.7 – 14.1) | |||||||

| La Florida, Chile | |||||||

| Czepita (2008) [38] | Urban: 1200 | 10-14 years | ≥ + 1.50 D | Not stated | Urban: 7.1 | 5.6 – 8.5 | Urban (N = 1200): |

| Right eye | Rural: 30.8 | 27.9 – 33.7 | 10 years: 8.3% (5.2 – 11.3) | ||||

| cr | 11 years: 4.1% (1.6 – 6.6) | ||||||

| 12 years: 9.9% (5.8 – 14.0) | |||||||

| 13 years: 7.7% (4.3 – 11.1) | |||||||

| 14 years:5.3% (2.2 – 8.3) | |||||||

| Rural (n = 1006) | |||||||

| 10 years: 33.3% (27.1 – 39.5) | |||||||

| Czeczecin, Poland | Rural:1006 | 11 years: 28.4% (22.1 – 34.7) | |||||

| 12 years: 26.9% (20.9 – 32.9) | |||||||

| 13 years: 30.5% (24.4 – 36.5) | |||||||

| 14 years:36.4% (28.7 – 44.1) | |||||||

| Kleinstein (2003) [39] CLEERE Study, USA | 2523 | 5-17 years | ≥ + 1.25 D in each meridian | Not stated | 12.8 | 11.5 – 14.1 | Not available |

| Right eye | |||||||

| ca | |||||||

| Zadnik (2003) [40] | 2583 | 7-12 years | ≥ + 1.25 D§ | Not stated | 8.6 | Not available | Not available |

| Right eye | |||||||

| ca | |||||||

| CLEERE Study, USA | |||||||

| Dandona (1999) [41] | 599 | 0-15 years | ≥ + 1.00 D | Not stated | 41.14 | 24.9 – 58.0 | Not available |

| Eye with higher refractive error | |||||||

| Andhra Pradesh, India | |||||||

| cr | |||||||

| Shrestha (2011) [42] | 2236 | 5-16 years | ≥ + 1.00 D† | Not stated | 20,3 | Not available | Not available |

| Either/both eyes | |||||||

| cr | |||||||

| Jhapa, Nepal | |||||||

| Czepita (2007) [43] | 4422 | 6-18 years | ≥ + 1.00 D | Not stated | 13.05 | Not available | 6 years: 36.5% (31.8 – 41.3) |

| 7 years: 19.2% (15.4 – 22.9) | |||||||

| 8 years: 17.4% (13.8 – 21.0) | |||||||

| 9 years 11.3% (8.3 – 14.3) | |||||||

| 10 years: 11.0% (8.0 – 14.0) | |||||||

| 11 years: 10.9% (8.0 – 14.0) | |||||||

| 12 years: 8.3% (5.6 – 10.9) | |||||||

| 13 years: 11.8% (8.1 – 15.5) | |||||||

| 14 years: 8.2% (5.3 – 11.2) | |||||||

| 15 years: 8.6% (5.4 – 11.8) | |||||||

| 16 years: 2.8% (0.6 – 5.1) | |||||||

| 17 years: 2.5% (0.3 – 4.7) | |||||||

| 18 years: 3.2% (0.7 – 5.7) | |||||||

| Right eye | |||||||

| cr | |||||||

| Szczecin, Poland | |||||||

| Vilareal (2003) [44] | 1035 | 12-13 years | ≥ + 1.00 D | Not stated | 6 | Not available | Not available |

| ca | |||||||

| Monterrey, Mexico | |||||||

| Vilareal (2000) [45] | 1045 | 12-13 years | ≥ + 1.00 D | Not stated | 8.4% | Not available | Not available |

| Right eye | |||||||

| cr | |||||||

| Götemborg area Sweden | |||||||

| Hashemi (2004) [46] | 412 | 5-15 years | ≥ + 0,50 D | Not stated | 78.6 | 74.6 – 82.6 | Not available |

| Right eye | |||||||

| ca | |||||||

| Tehran, Iran | |||||||

| Dandona (2002) [47] | 2603 | 0-15 years | ≥ + 0,50 D | Not stated | 62.6 | 57.0 – 68.1 | Not available |

| Eye with higher refractive error | |||||||

| Andhra Pradesh, India | |||||||

| cr | |||||||

| Niroula (2009) [48] | 964 | 10-19 years | ≥ + 0,50 D‡ | Not stated | 1.24 | Not available | Not available |

| Both eyes | |||||||

| cr | |||||||

| Pokhara, Nepal |

y = years (age); CI: Confidence Interval; SE: mean spherical equivalent; RESC: The Refractive Error Study in Children; ca: cycloplegic autorefraction; cr: cycloplegic retinoscopy.

† study did not mention SE in its definition of hyperopia.

‡ It was considered +0,5 diopter or more spherical power.

§ Define as +1.25 D or more in both meridians.

The meta-analysis was performed using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet [49]. Differences in the populations studied, especially ethnicity, have a non-random impact on prevalence. The random effects model was therefore used in order to obtain the effect summary and its confidence interval. The adequacy of the effect summary depends on the homogeneity assumption. Heterogeneity was measured using the Q test and was quantified using I2 statistics. Heterogeneity tests having a p-value <0.1 were considered statistically significant.

This systematic review was performed according to the PRISMA [50] and MOOSE [51] Statements. The study was approved by the Federal University of Pelotas School of Medicine Research Ethics Committee and follows the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines [52].

Results

Hyperopia prevalence by age in children

The review included 40 cross-sectional studies on prevalence and/or assessment of risk factors for hyperopia. Eighteen studies were conducted in Asia, of which six were carried out in China and five in India. The other Asian countries were: Nepal (three studies), Malaysia (two studies), Cambodia and the Democratic Republic of Laos (one study each). Seven studies are from Europe (two were conducted in the United Kingdom; Poland and Sweden carried out two studies each and one study was conducted in Finland). Six studies are from the Middle East (Iran). Four studies were conducted in Australia, two in the United States and one study each in South Africa, Chile and Mexico.

All samples of children used in the studies were population-based or school-based, except the study that used a sample of children from a private school in Xiamen, China [13].

In most studies included in this review, the cut-off point for hyperopia was based on the Refractive Error Study in Children (RESC) protocol used in multicenter studies [53]. Spherical equivalent refraction (SE) for hyperopia was ≥ +2.00D (one or both eyes, if none the eyes are myopic). The studies used data from one or both eyes to determine prevalence. However, some studies used different cut-off points [38–48, 54], thus underestimating or overestimating hyperopia prevalence compared to studies using the RESC protocol. Some studies performed the examination on the right eye only, thereby underestimating the prevalence of hyperopia [38, 43].

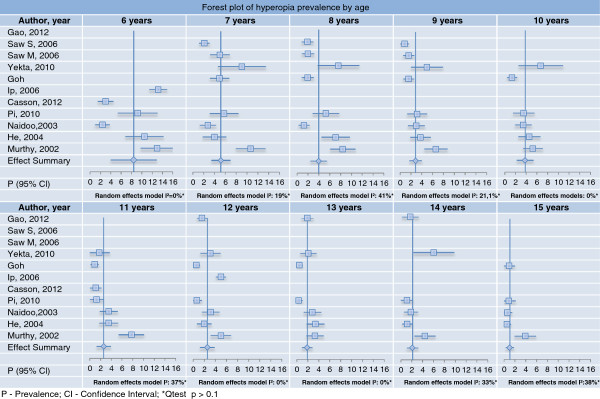

The meta-analysis indicates that hyperopia prevalence decreases as age increases, with a summary prevalence measure of 5% at age 7, 2-3% between age 9 and 14 and around 1% at age 15. Various studies of children aged 6 to 8 presented large confidence intervals. I2 indicates homogeneity among the studies regarding specific age (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of hyperopia prevalence by age.

In studies using the 5-15 age group and ≥ +2.00 D (RESC) cut-off, hyperopia prevalence ranged from 2.1% [18] to 19.3% [25, 37] (Table 1).

Although there is literature indicating a direct association between AL and age, only a few studies have assessed its distribution by specific ages [40, 55].

Gender and hyperopia in children

Most studies showed no statistically significant association between gender and hyperopia (Table 2) [9, 11, 14, 17, 19, 20, 23, 25–27, 30, 32, 34, 36, 39–41, 46–48, 56, 57]. With regard to ocular components, on average girls appear to have shorter AL when compared to boys [3, 30, 55, 58].

Table 2.

Hyperopia associated factors

| Author (Year) | Location | Hyperopia associated factors |

|---|---|---|

| Ip (2008) [29] | Sydney Myopia Study (SMS) | GENDER: Age 6, girls were more hyperopic 15.5% (95%CI 12.7 – 18.4) than boys 10.9% (95%CI 8.5 – 13.2) (p = 0.005). Age 12, boys: 5.1% (95%CI 3.8–6.5), girls: 4.7% (95%CI 3.5–6.0), NS. |

| Australia | ||

| ETHNICITY: At age 6, more prevalent in European Caucasian 15.7% (95%CI 13.2–18.2) when compared with East Asian 6.8% (95%CI 4.0–9.5) and South Asian 2.5% (95%CI 0.0–7.5). East Asian, South Asian and Middle Eastern 8.4% (95%CI 1.6–15.2) do not present differences among their prevalence. At age 12, more prevalent in European Caucasian, 6.4% (95%CI 5.2–7.7) than East Asian 2.0% (95%CI 1.0–3.0). No difference between East Asian and Middle Eastern 7.4% (95%CI 2.7–12.0) and European Caucasian and Middle Eastern. | ||

| PARENTAL EDUCATION: Age 12, Maternal Education, (p = 0.055). | ||

| SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATUS: Age 6, Maternal Occupation, (p = 0.02). Home Ownership or Paternal Education or Employment (p > 0.1), after adjusted for demographic factors (gender, ethnicity, parental education, parental employment). Parental Employment was associated with moderate hyperopia (≥ + 2.00 D), (p = 0.02). | ||

| Ip (2008) [30] | Sydney Myopia Study (SMS) | GENDER: Age 11–15, no difference among boys 3.6% (95%CI 2.6–4.7) and girls 3.3% (95% CI 2.2–4.4). Age 12, girls showed a lower mean spherical equivalent (SE) (+0.39D) than boys (+0.58D), (p = 0.04). |

| Australia | ||

| ETHNICITY: European Caucasian 4.4% (95%CI 3.6–5.3) are more likely to have moderate hyperopia (≥ + 2.00 D) than East Asian 1.1% (95%CI 0.2–2.1), South Asian 0.0%(-) and other mixed ethnicity 1.7% (95%CI 0.0–3.6). Middle Eastern 6.1% (95%CI 1.5–10.7) are more likely to have moderate hyperopia than South Asian. There was no difference between European Caucasian and Middle Eastern. Age 12, Middle East showed a lower mean of SE (+0.71) than Caucasian (+0.82D) (p = 0.03). Caucasian had the highest mean SE (+0.82D) when compared to all ethnicities together (+0.04D), (p < 0.0001). | ||

| Ip (2008) [59] | Sydney, Australia | OUTDOOR ACTIVITIES: Age 12, greater time, (β coefficient = 0.03, p <0.0001), and weakly correlated with near-work activities (r =0.1, p < 0.0001). |

| NEAR WORK ACTIVITIES: Parental Reports of Close Reading Distance (<30 cm) (p < 0.0001), after adjustment for age, sex, ethnicity, and school type. | ||

| Rose (2008) [8] | Sydney Myopia Study (SMS) | OUTDOOR ACTIVITIES: Age 6 and 12, Greater Number of Hours, p = 0.009 and p = 0.0003 respectively, after adjustment for gender, ethnicity, parental myopia, near work, maternal and parental education, and maternal employment. |

| Australia | ||

| NEAR WORK ACTIVITIES: Age 12, Greater Levels of Near-work Activity, p =0.8. | ||

| Maul (2000) [37] | La Florida, Chile | AGE: 5–15, inverse relation (p < 0.05). |

| GENDER: Age 5–15, girls OR = 1.21 (95% CI 1.03-1.43). | ||

| Zhao (2000) [10] | Shunyi, China | AGE: 5–15, inverse relation OR = 0.75 (95% CI 0.71-0.79). |

| GENDER: Age 5–15, girls OR = 1.51 (95%CI 1.08-2.13). | ||

| Zhan (2000) [13] | Xiamen city, Xiamen Countryside and Singapore, China | RESIDENCE AREA: Age 6–7, Residence Zone, p = 0.50. |

| He (2004) [11] | Guangzhou, China | AGE: 5–15, inverse relation OR = 0.77 (95% CI 0.73-0.81). |

| GENDER: Age 5–15, NS p = 0.233. | ||

| PARENTAL EDUCATION: inverse relation OR = 0.81 (95%CI 0.66-0.98). | ||

| Pi (2010) [14] | Yong Chuan District, Western China | AGE: 6 – 15, inverse relation OR = 0.831 (95%CI 0.728-0.948), p < 0.01. |

| GENDER: Age 6–15, χ2 = 2.977, NS p = 0.08. | ||

| Dandona (2002) [47] | Andhra Pradesh, India | AGE: 0 – 5, were more hyperopic than those 10 – 15, OR = 3.34 (95%CI 2.69–4.14), p < 0.05. and 6 – 9 were more hyperopic than 10 – 15, OR = 1.72 (95%CI 1.41–2.10), p < 0.05 |

| GENDER: Age 0–15 OR:1.19 (95%CI 0.76 – 1.86), NS. | ||

|

SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATUS: Base Group: extreme lower income, Upper OR = 2.27% (95%CI 0.59 – 8.77), Middle OR = 2.21% (95%CI 0.89 – 5.50), Lower OR = 1.76% (95%CI 0.74 – 4.19). RESIDENCE AREA: Two Rural Areas, OR = 2.84 (95%CI 2.16-3.75) and OR = 1.50 (95%CI 1.17-1.92) when compared with Urban. | ||

| Laatikainen (1980) [33] | Uusimaa County, Finland | AGE: 7–15 years, inverse relation, x2 = 28.617, p < 0.0005. |

| Grönlund (2006) [32] | Gothenburg, Sweden | AGE: 4 – 15, Correlation SE OD: r = -0.37, p < 0.0001 and SE OS: R = -0.33, p < 0.0001. |

| GENDER: Age 4–15, SE OD (p = 0.61) and SE OS: (p = 0.85). | ||

| OBS: The mean and standard deviation (SD) of the spherical equivalent (SE) was used in this study. | ||

| Dandona (2002) [22] | Andhra Pradesh, India | AGE: 7–15, NS. |

| GENDER: Age 7–15, NS. | ||

| PARENTAL EDUCATION: Education of the father (grade level achievement: none, 1–5, 6–12, 13–15, 15 or more), NS. | ||

| SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATUS: Extreme Lower, Lower, Middle, Upper, NS. | ||

| Dandona (1999) [41] | Andhra Pradesh, India | AGE: 0 – 15, NS. |

| GENDER: Age 0–15, NS. | ||

| SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATUS: Extreme Lower, Lower, Middle, Upper, NS. | ||

| Murthy (2002) [21] | New Delhi, India | GENDER: Age 11–13, girls OR = 1.72 (95% CI 1.05-2.81). |

| PARENTAL EDUCATION: Age 11–13, Child Education, inversely associated OR = 0.89 (95%CI 0.81-0.99). | ||

| Hashemi (2004) [46] | Tehran, Iran | AGE 5–15, inverse association, S p < 0.001. |

| GENDER: Age 5–15, Boys, 78.6% (95%CI 74.6 – 82.6), Girls, 73.2 (95%CI 68.5 – 77.9), NS. | ||

| Fotouhi (2007) [9] | Dezful, Iran | AGE 7–15, inverse relation OR = 1.73 (95%CI 0.83-0.94), p < 0.001. |

| GENDER: Age 7–15, boys 16.1% (95% CI 11.0–21.1), girls 16.1% (95%CI 11.0–21.1), NS. | ||

| RESIDENCE AREA: Rural, OR = 2.0 (95%CI 1.09-3.65). | ||

| Yekta (2010) [27] | Shiraz, Iran | AGE: 7–15, inverse relation OR = 0.84 (95%CI 0.73-0.97), S, p = 0.021. |

| GENDER: Age 7–15, boys: 5.17% (95%CI 3.19–7.15), girls, 4.90% (95%CI 2.32–7.48), NS, p = 0.863. | ||

| Ostadimoghaddam (2011) [25] | Mashhad, Iran | AGE: 5 – 15 inverse relation, S, (p < 0.001). |

| GENDER: Age 5–15, NS, p = 0.724. | ||

| Goh (2005) [17] | Gombak District, Malaysia | AGE: 7–15, inverse relation OR = 0.72 (95%CI 0.62-0.82). |

| GENDER: Age 7–15, boys, 1.7% (95%CI 1.1–2.3), girls, 1.4% (95%CI 0.8–2.1). | ||

| ETHNICITY: Age 7–15, “other” ethnicities were more hyperopic OR = 3.72 (95%CI 1.34-10.35) than Malaysian and Chinese. No differences were found among Malaysian 1.5% (95%CI 1.1–1.9), Chinese 1.1% (95%CI 0.4–1.7) or Indian 2.0% (95%CI 0.1–3.9). | ||

| PARENTAL EDUCATION: Parental with highest level of schooling, NS. | ||

| Varma (2009) [56] | Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study Group (MEPEDS) | AGE: 6 – 72 months, Hispanic children, inverse relation, (6–11 months) vs (60–72 months) OR = 1.46 (95%CI 1.08–1.98) (P = 0.0017). Age 6–72 months, African-American, NS. |

| Los Angeles County, California USA | ETHNICITY: Age 6–72 months, Hispanic were more hyperopic 27.1% (95%CI 24.0 – 30.1) than African-American 21.1% (95%CI 17.9 – 24.3), after controlling for age, S, p < 0.001. Age 6–11 months and 36–47 months Hispanic are more hyperopic 35.1% (95%CI 29.7 – 40.5) and 29.9% (95%CI 26.0 – 33.8) than African-American, 18.1% (95%CI 13.5 – 22.7) and 20.7% (95%CI 17.3 – 24.1) respectively. | |

| Pokharel (2000) [18] | Mechi Zone, Nepal | AGE: 5 – 15, as continuous variable, NS. |

| GENDER: Age 5–15, girls OR = 1.44 (95%CI 1.02-2.03). | ||

| Czepita (2007) [43] | Czeczecin, Poland | AGE 6–18, negative correlation, Sr = 0.907, S, p < 0.001 |

| GENDER: Age 6–18, boys 40.3%(95% CI 38.5 – 42.1) are more hyperopic than girls, 35.3% (95%CI 33.6 – 37.0). | ||

| Naidoo (2003) [36] | Durban area, South Africa | AGE: 5 – 15 years, NS. |

| GENDER: Age 5–15, NS. | ||

| PARENTAL EDUCATION: parent with the highest education (grade level achievement: none, 1–5, 6–12, 13–15, 15 or more), NS. | ||

| Garner (1990) [60] | Island of Efaté, Republic of Vanatu, Melanesia | AGE: 6 – 17, age groups Melanesian, NS. |

| Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia | ETHNICITY: Age 6, Malaysian were more hyperopic than Melanesian. | |

| Kleinstein (2003) [39] | Collaborative Longitudinal Evaluation of Ethnicity and Refractive Error Study Group | ETHNICITY: Age 5 – 17, white are more hyperopic 19.3% (95%CI 16.9 – 21.7) than Asians 6.3% (95%CI 4.1 – 8.4) and African-Americans 6.4% (95%CI 4.3 – 8.5), x2 = 236.15, S, p < 0.001. Age 5–17 white didn’t differ from Hispanics 12.7% (95% CI 9.7 – 15.7), NS, p = 0.48. Age 5–17 Asians and Africa-Americans, NS, p = 0.07. |

| (CLEERE) Study | ||

| Eutaw, Alabama; Irvine, California and Houston, Texas USA | ||

| GENDER: Age 5–17, boys 12.6% (95%CI 10.8 – 14.4) are more hyperopic than girls 13.1% (95%CI 11.2 – 15.0). | ||

| Zadnik (2003) [40] | Collaborative Longitudinal Evaluation of Ethnicity and Refractive Error Study Group | AGE: Age 6 to 7 and age 8 were more hyperopic than 9 to14, S, p < 0.0001. |

| (CLEERE) Study | ||

| Eutaw, Alabama; Irvine and Orinda, California and Houston, Texas USA | ||

| Giordano (2009) [54] | Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study (BPEDS) | ETHNICITY: 6 – 72 months, white are more hyperopic (≥ + 1.00) than African-American OR = 1.62 (95%CI 1.51-1.74). White, 6 – 11: 33.0% (95%CI 22.9 – 43.1), 12 – 23: 30.3% (95%CI 23.5 – 37.1), 36 – 47: 27.5% (95%CI 21.5 – 33.5), 48 – 59: 33.3% (95%CI 26.8 – 39.9) and 60 – 72: 31.5% (95%CI 24.5 – 38.4) months are more hyperopic (≥ + 2.00D) than African American at same age ranges, 21.2% (95%CI 12.4 – 30.0, 15.7% (95%CI 10.5 – 20.9), 16.2% (95%CI 11.5 – 20.9), 17.2% (95%CI 12.6 – 21.8) and 17.4% (95%CI 12.6 – 22.1) respectively. |

| USA | ||

| Borchert (2011) [61] | Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study (BPEDS) | AGE: 6 – 72 months. Those 12 – 23 months and 24 – 35 months are more hyperopic than 60 – 72 months OR = 0.81(95%CI 0.68 – 0.97) and OR = 0.74 (95%CI 0.62 – 0.88) respectively. |

| USA | ETHNICITY: Age 6–72 months, Non-Hispanic white, children are more hyperopic than African-American OR = 1.63 (95%CI 1.43 – 1.87). Age 6–72 months, Hispanic white are more hyperopic than African-American OR = 1.49 (95%CI 1.32 – 1.68). | |

| SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATUS: Age 6–72 months with Health insurance, OR = 1.51 (95%CI 1.12 – 1.69). | ||

| O’Donoghue (2012) [34] | Northern Ireland Childhood Errors of Refraction | AGE: 6 – 7 are more hyperopic 26% (95%CI 20–33) than 12 – 13 years, 14.7% (95%CI 9.9 - 19.4), p < 0.005. |

| (NICER) | GENDER: Age 6–7, NS. Age 13–13, S. | |

| Northern Ireland | ||

| Dirani (2010) [57] | The Strabismus, Amlyopia and Refractive Errors in Singaporean children | AGE: 6 – 72 months, inverse relation, Age 6 – 11.9 months 15.7% (95%CI 10.6 – 22.2), Age 24 – 35.9 months 6.8% (95%CI 4.6 – 9.6), Age 36 – 47.9 months 5.1% (95%CI 3.3 – 7.3) and age 60 – 72 months 5.7% (95% CI 3.8 – 8.0), S, p trend = 0.001. |

| (STARS) | ||

| Singapura | GENDER: Age 6–72 months, boys 6.6% (95%CI 5.1 – 7.7), girls: 9.4% (95%CI 7.9 – 11.1), NS, p = 0.75. | |

| Casson (2012) [20] | Vientiane Province, Lao PDR | GENDER: 6 – 11, NS, p = 0.95. |

| Uzma (2009) [23] | Hyderabad, Índia | GENDER: 7 – 15, Urban, boys 1.5% (95%CI 0.7–2.3), girls, 1.4% (95%CI 0.6–2.2). Rural, boys, 2.7% (95%CI 1.3–4.1), girls, 2.1% (95%CI 0.9–3.3), NS. |

| RESIDENCE AREA: Age 8, 9, 12 and 13, Rural, are more hyperopic than urban, 8.1% (95%CI 5.4–10.8) v 2.0% (95%CI 0.4–3.6), 7.3% (95%CI 3.7–10.9) v 1.7% (95%CI 0.8–2.6), 3.2% (95%CI 1.6–4.8) v 0.4% (95%CI 0.0–0.8) and 2.4% (95%CI 0.9–3.9) v 0.2% (95%CI 0.0–0.4), respectively. | ||

| Rezvan (2012) [26] | Bojnourd, Iran | AGE: 6 – 17, inverse relation, S, p < 0.0001. |

| GENDER: Age 6–17, boys, 4.4% (95%CI 2.8–5.9), girls, 6.1% (95%CI 4.5–7.7), NS. | ||

| Saw (2006) [16] | Gombak District, Kuala Lumpur Malaysia Singapore | AGE: 7, Malaysian are more hyperopic (5%) than Singapore (2.1%), Prevalence difference, -22.9% (95%CI -24.8 to -20.9), S, p < 0.001. |

| GENDER: Age 7–9, Malaysian boys are more hyperopic (3.2%) than Singaporean boys (1.3%), Prevalence difference, -21.9% (95%CI -23.3 to -20.6), p < 0.001. | ||

| ETHNICITY: Age 7–9, Singaporean, are less hyperopic (1.7%) than Malaysian (2.9%), Prevalence difference, -21.1% (95%CI -22.1 to -20.2), p = 0.005. | ||

| PARENTAL EDUCATION: Age 7–9, Completed Education Level of the Father, NS. | ||

| OBS: Differences in the prevalence rates of hyperopia between Malaysia and Singapore were considered significant if the 95% confidence intervals of the differences in the prevalence rates did not cross zero and p values were <0.05. | ||

| Logan (2011) [35] | Birmingham, England (AES) | ETHNICITY: Age 6–7, White European are more hyperopic, 22.9% (95%CI 12.9% – 32.8%) than South Asian 10.3% (95%CI 6.2% - 14.4%) and Black African Caribbean 9.1% (95%CI 0.5 – 17.7). South Asian v Black African Caribbean, NS. Age 12 – 13, White European 10.4% (95%CI 4.8% – 16.1%) v South Asian 2.6% (95%CI 0.0 - 5.6%), NS. |

| Czepita (2008) [38] | Szeczecin, Poland | RESIDENCE AREA: Age 6–18, living in the city, are less hyperopic than those in the countryside, S, p < 0.001. |

| Gao (2012) [19] | Phnom Penhn, Cambodia | AGE: 12, 13 and 14, Prevalence Rates, 0.7% (95%CI 0.4–1.0), 0.7% (95%CI 0.4–0.9) and 0.8% (95%CI 0.3–1.3) respectively, NS. |

| GENDER: Age 12–14, boys: 0.6% (95%CI 0.3–0.8), girls, 0.9% (95%CI 0.6–1.1), NS. | ||

| RESIDENCE AREA: Age 12–14, urban, 1.4% (95%CI 0.1–1.7) v rural, 0.4% (95%CI 0.2–0.6), NS. | ||

| Niroula (2009) [48] | Pokhara, Nepal | GENDER: 10 – 19, boys, 1.48% (95%CI 0.3–2.6), girls, 1.02% (95%CI 0.1–1.9), NS. |

OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; SE: spherical equivalence; NS: non-significant; S: significant.

According to some studies however, girls are more likely to be hyperopic when compared to boys. In Australia, girls aged 6 are more likely to be hyperopic (15.5%) (95% CI 12.7-18.4) than boys of the same age (10.9%) (95% CI 8.5-13.2) (p = 0.005), although this difference was not found among children aged 12 in the same study [29]. Similarly, studies conducted in Chile, China and Nepal with children aged 5-15 years showed that girls are more likely to be hyperopic than boys: OR = 1.21 (95% CI 1.03-1.43) [37], OR = 1.51 (95% CI 1.08-2.13) [10] and OR = 1.44 (95% CI 1.02-2.03), [18] respectively. However, in a study conducted in Poland boys aged 6-18 years showed higher hyperopia prevalence (40.3%) (95% CI 38.5-42.1) when compared to girls in the same age range (35.3%) (95% CI 33.6 - 37.0) [43].

Ethnicity and hyperopia in children

Some studies have shown that there is no significant difference in hyperopia prevalence between Caucasian and Hispanic children [39] or between Caucasian and Middle East children [29, 30]. There is also evidence that Caucasian children are more hyperopic than African-American [39, 54, 56, 61], Black [35] and Asian (East and South Asia) children [29, 30, 35]. With regard to specific ethnic groups, there is no difference between hyperopia prevalence among Malay, Chinese and Indian children [17], although Malaysian children are more hyperopic than Singaporean (p = 0.005) [16] and Melanesian children [60]. It was also found that children of other ethnicities (not specified) are more likely to be hyperopic than Melanesian children OR = 3.72 (95%CI 1.34-10.3) [17] (Table 2).

In the South African study, hyperopia prevalence among children aged 7 years was only 2.8% [36]. The majority of the South African population is Black, followed by Asians (9.4%) and Caucasians (6.6%). In the Malay study, hyperopia prevalence among children aged 10 years was 1.4% [17]. The ethnic composition of the region is mostly Malay but approximately 28% of individuals have Chinese origin. The lowest hyperopia prevalence (0.5%) was found in a study in Guangzhou, one of the most developed cities in southern China [11].

Regarding ocular components in different ethnicities, on average it was found that AL is shorter and CC is flatter among Caucasian children [3, 30, 62].

Parental education and socio-economic status and hyperopia in children

Most of the reviewed studies showed no significant association between parental education and hyperopia in children (Table 2) [16, 17, 21, 22, 27, 36, 47]. In an Australian study, although there was no significant association between paternal education and hyperopia among children under 6 years of age, maternal education showed an inverse association with the presence of hyperopia among children aged 12 (p = 0.055) [29]. In a Chinese study the high level of parental education was a protective factor against the presence of hyperopia among children aged 5-15 years, OR = 0.81 (95% CI 0.73 - 0.81) [11].

Regarding socio-economic status, maternal employment is directly related to hyperopia in 6-year-old children in Australia (p = 0.02), although it is not associated with family income or paternal employment (p > 0.1) [29]. In the same study, an association between both parents being employed and hyperopia ≥ +2.00 D was found among 6-year-old children, after adjusting for gender, ethnicity and parental education (p = 0.02) [29].

Each of the three Indian studies with children aged 0-15 years had different cut-offs for hyperopia (≥ + 2.00D, ≥ + 1.00D and ≥ +0.5 D) but none of them showed association between socio-economic status (classified according to family income) and hyperopia [22, 41, 47].

In a study conducted in the United States, children aged 6-72 months with health insurance coverage showed a greater chance of having hyperopia when compared to those with no health insurance, OR = 1.51 (95% CI 1.12 - 1.69) [61].

Area of residence and hyperopia in children

There are few studies on the association between area of residence (urban or rural) and hyperopia prevalence in children. In an Indian study, children aged 0-15 years who lived in two rural areas were more likely to be hyperopic when compared to those living in urban areas, OR = 2.84 (95% CI 2.16-3.75) and OR = 1.50 (95% CI 1.17-1.92) respectively (Table 2) [47]. In another study conducted in India with children aged 7-15 years, those aged 8, 9, 12 and 13 years living in rural areas presented higher prevalence of hyperopia than those of the same age living in urban areas (Table 2) [23].

An Iranian study showed that children aged 7-15 years living in rural areas are more likely to be hyperopic than those living in urban areas, OR = 2.0 (95% CI 1.09-3.65) [9] and another study in Poland reported that children aged 6-18 years living in urban areas showed lower frequency of hyperopia when compared to children living in rural areas (p < 0.001) (Table 2) [38].

Two reviewed articles (one conducted in China with children aged 6-7 years and the other in Cambodia with children aged 12-14 years) showed no significant association between area of residence and hyperopia [13, 19] In the Cambodian study, hyperopia prevalence rates among children living in urban and rural areas were 1.4% (95% CI 0.1 - 1.7) and 0.4% (95% CI 0.1 - 1.9) respectively (Table 2) [19].

Outdoor activities and hyperopia in children

Rose et al. noted that children aged 6 and 12 years in Australia who spent more time per week doing outdoor activities (outdoor sports, picnics and walking) were more hyperopic than those who spent less time practicing these activities, adjusted for gender, ethnicity, presence of myopia in parents, near activities, and maternal and paternal education and working mothers (p = 0.009 and p = 0.0003, respectively) (Table 2) [8]. These authors also noted that there was a statistically significant trend toward greater hyperopic spherical equivalent refraction as tertiles of outdoor activities increased and tertiles of near activities decreased [8]. In the same study, Rose concluded that hyperopic spherical equivalent refraction was more common in children who dedicated less time to near activities and more time to outdoor activities [8].

Spending time engaged in outdoor activities was slightly associated with hyperopia (β = 0.03, p < 0.0001) among 12-year-old children in Australia. That study found that children who performed near activities (reported by parents), such as reading distance (<30cm), were significantly associated with less hyperopia (p < 0.0001), after adjusting for age, gender, ethnicity and type of school (Table 2) [59].

In the United States, Mutti et al. examined 366 children with mean age of 13.7 ± 0.5 years and showed (using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test) that myopic children spend more time reading for pleasure (p = 0.034) and less time playing sports (p = 0.049) compared with hyperopic children [7].

Discussion

There are several studies on hyperopia prevalence in childhood, but a great difficulty arises when attempting to compare them. This is partly due to the methodological characteristics of each study. Regarding the diopter value, there is no consensus on the cut-off point for diagnosing children as hyperopic, nor on what is the most appropriate measure: a greater, or lesser, hyperopic corneal meridian or spherical equivalent refraction [2]. However, cycloplegia followed by retinoscopy or autorefraction is the acceptable way of testing to diagnose ametropias, although doubts remain as to its accuracy in children with darker irises [63]. Most studies classify an individual as being hyperopic after binocular examination, but others use the eyes separately as unit samples or examine only one of the eyes (usually the right eye) relying on evidence of good correlation between ametropia in both eyes [2].

The RESC protocol has been used as a way of standardizing the methodology applied in studies on refractive errors, thus improving the comparability of results between child populations [53]. Hyperopia has an inverse association with age, is more common in Caucasian children and in those who live in rural areas or spend more time doing outdoor activities and it shows inconsistent results regarding association with gender, socio-economic status and parental education.

There is consistency among the studies about the inverse association between hyperopia and age. Although there are studies stating that slow growth in AL lasts until around the age of 12-14 years [5, 55, 64], emmetropization is minimal after the age of three, [6] and does not explain the decrease in hyperopia by age after 5 years-old.

Studies included in the meta-analysis were selected due to their methodological similarity and high response rate. The larger confidence intervals among those aged 6 to 8 indicate a less precise estimate of prevalence which is related to smaller sample size in these specific ages. However, it might also reflect greater difficulty in performing examinations in younger children, or greater variability in different populations in this age range, such as the heredity of refractive error or ocular characteristics of components such as axial length among different ethnicities.

The conflicting results when assessing the association between gender and hyperopia may be related to gender representativeness in the studies. On the one hand, the gender ratio is fairly even, suggesting good representativeness. Yet in some cultures girls have more difficulty in accessing schools, which could imply selection bias in hyperopia prevalence. On the other hand, females have greater acceptance and participation in studies, trials and interviews with scientific purposes which in turn could lead to positive selection bias [25].

The particularly low hyperopia prevalence could be partly explained by ethnicity, such as in Durban, South Africa [36], where the majority of the population are Black, followed by Asians. Regarding ocular components, axial length in both Africans and Asians is longer than in Caucasian individuals.

Literature shows that populations with high myopia prevalence rates generally have low hyperopia prevalence, as in China [11, 30]. This aspect may influence the prevalence of hyperopia in places where there is a considerably high density of Chinese ethnicity when compared to the native population, as in Durban and Gombak [17, 36].

No association was found between parental education and socio-economic status and hyperopia in children. As for ocular components, in the United States Lee observed a statistically significant association (p < 0.01) between years of education and larger AL in individuals aged 43-84 years, indicating that this aspect should be better studied in children [65].

Some authors point to geographical factors as potential determinants of ametropias, such as location and type of residence. They defend that greater levels of hyperopia may be found in people who live in rural areas and in houses, because they do more outdoor activities.

The controversy as to the impact of environmental factors on hyperopic spherical equivalent refraction in children still remains. Although theoretically near activities increase the demand of the accommodative process (hyperopic defocus), stimulating changes in the dimensions of ocular components (such as increases in AL) and thus decreasing the eye’s chance of remaining hyperopic [6], one cross-sectional study found very weak correlation between hours spent in near work activities and spherical equivalent [59]. Regarding outdoor activities, spending more time outdoors was associated with slightly more hyperopic refractions [59]. Theoretically, children who spend more hours per week doing outdoor activities do not require as much accommodation to practice them. Thus, the stimulation of ocular growth decreases owing to low accommodative demand [8]. The empirical evidence is insufficient to be able to understand the relationship between environmental factors and hyperopia.

The role of light intensity must also be considered. Since light is usually of greater intensity outdoors, eye exposure results in a more constricted pupil, increasing the depth of focus and leading to a less unfocused image [8]. In addition, dopamine released by light stimulus on the retina can contribute directly to inhibiting ocular growth [8, 66].

Conclusion

The large variability of hyperopia prevalence raises questions about the ability of demographic, socio-economic and environmental factors to completely explain the hyperopia causal chain. Considering that more myopic populations or those with earlier onset of myopia may be populations with earlier or greater reductions in hyperopia, in view of the complementarity of these phenomena, the causes of the decrease in hyperopia prevalence may be common to those explaining the increase in myopia with age.

Future studies should refine the evaluation of these factors, particularly the role of outdoor activities and ethnicity, as well as exploring other potential risk factors such as heredity or diet. In order to improve the consistency of analysis, refractive error measurement needs to be standardized using the RESC Protocol and using cycloplegia to perform refractive examination. It is also important to have population-based or school-based representative samples, with low percentages of loss to follow-up and sufficiently large samples to be able to stratify by specific age. More studies on those younger than 9 years-old and with larger samples are necessary in order to obtain a more precise prevalence estimate.

AAO recommends undercorrection of hyperopia, however despite the fact that a large percentage of hyperopia appears to be benign at very early ages, a significant number may go on to develop sequelae. Furthermore, it is necessary to deepen the understanding about the interactions among hyperopic refractive error and accommodative and binocular functions as a way of identifying groups of hyperopic children at risk of developing visual, academic and even cognitive function sequelae [2].

Acknowledgements

This systematic review is funded by the Federal Agency for the Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES) of the Brazilian Ministry of Education.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

VDC and AGF planned the study, conducted the data analysis and wrote the paper. MLVC and MAPV contributed to the planning of the study and revising of the paper. RDM conducted the data analysis and revising of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Victor Delpizzo Castagno, Email: vicastagno@hotmail.com.

Anaclaudia Gastal Fassa, Email: anaclaudia.fassa@gmail.com.

Maria Laura Vidal Carret, Email: mvcarret@hotmail.com.

Manuel Augusto Pereira Vilela, Email: mapvilela@gmail.com.

Rodrigo Dalke Meucci, Email: rodrigodalke@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Rosner J. The still neglected hyperope. Optom Vis Sci. 2004;81(4):223–224. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200404000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tarczy-Hornoch K. The epidemiology of early childhood hyperopia. Optom Vis Sci. 2007;84(2):115–123. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e318031b674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ojaimi E, Rose KA, Morgan IG, Smith W, Martin FJ, Kifley A, Robaei D, Mitchell P. Distribution of ocular biometric parameters and refraction in a population-based study of Australian children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(8):2748–2754. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein AP, Suktitipat B, Duggal P, Lee KE, Klein R, Bailey-Wilson JE, Klein BE. Heritability analysis of spherical equivalent, axial length, corneal curvature, and anterior chamber depth in the Beaver Dam Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(5):649–655. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uretmen O, Pamukcu K, Kose S, Egrilmez S. Oculometric features of hyperopia in children with accommodative refractive esotropia. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2003;81(3):260–263. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2003.00062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mutti DO. To emmetropize or not to emmetropize? The question for hyperopic development. Optom Vis Sci. 2007;84(2):97–102. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e318031b079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mutti DO, Mitchell GL, Moeschberger ML, Jones LA, Zadnik K. Parental myopia, near work, school achievement, and children's refractive error. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43(12):3633–3640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rose KA, Morgan IG, Ip J, Kifley A, Huynh S, Smith W, Mitchell P. Outdoor activity reduces the prevalence of myopia in children. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(8):1279–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Mohammad K. The prevalence of refractive errors among schoolchildren in Dezful, Iran. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91(3):287–292. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.099937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao J, Pan X, Sui R, Munoz SR, Sperduto RD, Ellwein LB. Refractive Error Study in Children: results from Shunyi District, China. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129(4):427–435. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(99)00452-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He M, Zeng J, Liu Y, Xu J, Pokharel GP, Ellwein LB. Refractive error and visual impairment in urban children in southern china. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(3):793–799. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fan DS, Lam DS, Lam RF, Lau JT, Chong KS, Cheung EY, Lai RY, Chew SJ. Prevalence, incidence, and progression of myopia of school children in Hong Kong. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2004;45(4):1071–1075. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhan MZ, Saw SM, Hong RZ, Fu ZF, Yang H, Shui YB, Yap MK, Chew SJ. Refractive errors in Singapore and Xiamen, China–a comparative study in school children aged 6 to 7 years. Optom Vis Sci. 2000;77(6):302–308. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200006000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pi LH, Chen L, Liu Q, Ke N, Fang J, Zhang S, Xiao J, Ye WJ, Xiong Y, Shi H, Yin ZQ. Refractive status and prevalence of refractive errors in suburban school-age children. Int J Med Sci. 2010;7(6):342–353. doi: 10.7150/ijms.7.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He M, Huang W, Zheng Y, Huang L, Ellwein LB. Refractive error and visual impairment in school children in rural southern China. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(2):374–382. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saw SM, Goh PP, Cheng A, Shankar A, Tan DT, Ellwein LB. Ethnicity-specific prevalences of refractive errors vary in Asian children in neighbouring Malaysia and Singapore. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(10):1230–1235. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.093450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goh PP, Abqariyah Y, Pokharel GP, Ellwein LB. Refractive error and visual impairment in school-age children in Gombak District, Malaysia. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(4):678–685. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pokharel GP, Negrel AD, Munoz SR, Ellwein LB. Refractive Error Study in Children: results from Mechi Zone, Nepal. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129(4):436–444. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(99)00453-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao Z, Meng N, Muecke J, Chan WO, Piseth H, Kong A, Jnguyenphamhh T, Dehghan Y, Selva D, Casson R, Ang K. Refractive error in school children in an urban and rural setting in Cambodia. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2012;19(1):16–22. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2011.632703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casson RJ, Kahawita S, Kong A, Muecke J, Sisaleumsak S, Visonnavong V. Exceptionally Low Prevalence of Refractive Error and Visual Impairment in Schoolchildren from Lao People's Democratic Republic. Ophthalmology. 2012;119(10):2021–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murthy GV, Gupta SK, Ellwein LB, Munoz SR, Pokharel GP, Sanga L, Bachani D. Refractive error in children in an urban population in New Delhi. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43(3):623–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dandona R, Dandona L, Srinivas M, Sahare P, Narsaiah S, Munoz SR, Pokharel GP, Ellwein LB. Refractive error in children in a rural population in India. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43(3):615–622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uzma N, Kumar BS, Khaja Mohinuddin Salar BM, Zafar MA, Reddy VD. A comparative clinical survey of the prevalence of refractive errors and eye diseases in urban and rural school children. Canadian journal of ophthalmology Journal canadien d'ophtalmologie. 2009;44(3):328–333. doi: 10.3129/i09-030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hashemi H, Iribarren R, Morgan IG, Khabazkhoob M, Mohammad K, Fotouhi A. Increased hyperopia with ageing based on cycloplegic refractions in adults: the Tehran Eye Study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(1):20–23. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.160465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ostadimoghaddam H, Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Yekta A, Heravian J, Rezvan F, Ghadimi H, Rezvan B, Khabazkhoob M. Prevalence of the refractive errors by age and gender: the Mashhad eye study of Iran. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2011;39(8):743–751. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2011.02584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rezvan F, Khabazkhoob M, Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Ostadimoghaddam H, Heravian J, Azizi E, Khorasani AA, Yekta AA. Prevalence of refractive errors among school children in Northeastern Iran. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2012;32(1):25–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2011.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yekta A, Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Dehghani C, Ostadimoghaddam H, Heravian J, Derakhshan A, Yekta R, Behnia M, Khabazkhoob M. Prevalence of refractive errors among schoolchildren in Shiraz, Iran. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2010;38(3):242–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2010.02247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robaei D, Rose K, Ojaimi E, Kifley A, Huynh S, Mitchell P. Visual acuity and the causes of visual loss in a population-based sample of 6-year-old Australian children. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(7):1275–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ip JM, Robaei D, Kifley A, Wang JJ, Rose KA, Mitchell P. Prevalence of hyperopia and associations with eye findings in 6- and 12-year-olds. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(4):678–685. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ip JM, Huynh SC, Robaei D, Kifley A, Rose KA, Morgan IG, Wang JJ, Mitchell P. Ethnic differences in refraction and ocular biometry in a population-based sample of 11-15-year-old Australian children. Eye. 2008;22(5):649–656. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robaei D, Kifley A, Rose KA, Mitchell P. Refractive error and patterns of spectacle use in 12-year-old Australian children. Ophthalmology. 2006;113(9):1567–1573. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gronlund MA, Andersson S, Aring E, Hard AL, Hellstrom A. Ophthalmological findings in a sample of Swedish children aged 4–15 years. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006;84(2):169–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2005.00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laatikainen L, Erkkila H. Refractive errors and other ocular findings in school children. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1980;58(1):129–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1980.tb04576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Donoghue L, McClelland JF, Logan NS, Rudnicka AR, Owen CG, Saunders KJ. Refractive error and visual impairment in school children in Northern Ireland. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(9):1155–1159. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.176040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Logan NS, Shah P, Rudnicka AR, Gilmartin B, Owen CG. Childhood ethnic differences in ametropia and ocular biometry: the Aston Eye Study. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2011;31(5):550–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-1313.2011.00862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naidoo KS, Raghunandan A, Mashige KP, Govender P, Holden BA, Pokharel GP, Ellwein LB. Refractive error and visual impairment in African children in South Africa. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(9):3764–3770. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maul E, Barroso S, Munoz SR, Sperduto RD, Ellwein LB. Refractive Error Study in Children: results from La Florida, Chile. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129(4):445–454. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(99)00454-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Czepita D, Mojsa A, Zejmo M. Prevalence of myopia and hyperopia among urban and rural schoolchildren in Poland. Ann Acad Med Stetin. 2008;54(1):17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kleinstein RN, Jones LA, Hullett S, Kwon S, Lee RJ, Friedman NE, Manny RE, Mutti DO, Yu JA, Zadnik K, et al. Refractive error and ethnicity in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121(8):1141–1147. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.8.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zadnik K, Manny RE, Yu JA, Mitchell GL, Cotter SA, Quiralte JC, et al. Ocular component data in schoolchildren as a function of age and gender. Optom Vis Sci. 2003;80(3):226–36. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200303000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dandona R, Dandona L, Naduvilath TJ, Srinivas M, McCarty CA, Rao GN. Refractive errors in an urban population in Southern India: the Andhra Pradesh Eye Disease Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40(12):2810–2818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shrestha GS, Sujakhu D, Joshi P. Refractive error among school children in Jhapa, Nepal. J Optom. 2011;4(2):49–55. doi: 10.1016/S1888-4296(11)70041-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Czepita D, Mojsa A, Ustianowska M, Czepita M, Lachowicz E. Prevalence of refractive errors in schoolchildren ranging from 6 to 18 years of age. Ann Acad Med Stetin. 2007;53(1):53–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Villarreal GM, Ohlsson J, Cavazos H, Abrahamsson M, Mohamed JH. Prevalence of myopia among 12- to 13-year-old schoolchildren in northern Mexico. Optom Vis Sci. 2003;80(5):369–373. doi: 10.1097/00006324-200305000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Villarreal MG, Ohlsson J, Abrahamsson M, Sjostrom A, Sjostrand J. Myopisation: the refractive tendency in teenagers. Prevalence of myopia among young teenagers in Sweden. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2000;78(2):177–181. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.2000.078002177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hashemi H, Fotouhi A, Mohammad K. The age- and gender-specific prevalences of refractive errors in Tehran: the Tehran Eye Study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2004;11(3):213–225. doi: 10.1080/09286580490514513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dandona R, Dandona L, Srinivas M, Giridhar P, McCarty CA, Rao GN. Population-based assessment of refractive error in India: the Andhra Pradesh eye disease study. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2002;30(2):84–93. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-6404.2002.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Niroula DR, Saha CG. Study on the refractive errors of school going children of Pokhara city in Nepal. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2009;7(25):67–72. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v7i1.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neyeloff J, Fuchs S, Moreira L. BMC Research Notes. 2012. Meta-analysis and Forest plots using a microsoft excel spreadsheet: step-by-step guide focusing on descriptive data analysis. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker B, Sipe T, Thacker S: for the Metha-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. Metha-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting.JAMA 2000, (283):2008–2012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Association WM, editor. World Medical Association [WMA] World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Tóquio: World Medical Association; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Negrel AD, Maul E, Pokharel GP, Zhao J, Ellwein LB. Refractive Error Study in Children: sampling and measurement methods for a multi-country survey. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;129(4):421–426. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9394(99)00455-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Giordano L, Friedman DS, Repka MX, Katz J, Ibironke J, Hawes P, Tielsch JM. Prevalence of refractive error among preschool children in an urban population: the Baltimore Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(4):739–746. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.12.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Larsen JS. The sagittal growth of the eye. IV. Ultrasonic measurement of the axial length of the eye from birth to puberty. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh) 1971;49(6):873–886. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.1971.tb05939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Varma R, Abbot LV, Ayala G, Azen SP, Barak T, Borchert M, Chang J, Chen FK, Chon R, Cotter S, Cuestas C, Deneem J, Diaz J, DiLauro A, Donofrio J, Dozal C, Dzekov J, Foong AW, Gardner J, Garriot R, Lastra C, Lau J, Lin J, Martinez G, Milo K, McKean-Cowdin R, Moya C, Paz S, Penate A, Reiner A, et al. Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study Group. Prevalence of myopia and hyperopia in 6- to 72-month-old African American and Hispanic children: the Multi-Ethnic Pediatric Eye Disease Study. Ophthalmology. 2009;117(1):140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dirani M, Chan YH, Gazzard G, Hornbeak DM, Leo SW, Selvaraj P, Zhou B, Young TL, Mitchell P, Varma R, et al. Prevalence of refractive error in Singaporean Chinese children: the strabismus, amblyopia, and refractive error in young Singaporean Children (STARS) study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51(3):1348–1355. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin LL, Shih YF, Tsai CB, Chen CJ, Lee LA, Hung PT, Hou PK. Epidemiologic study of ocular refraction among schoolchildren in Taiwan in 1995. Optom Vis Sci. 1999;76(5):275–281. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199905000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ip JM, Saw SM, Rose KA, Morgan IG, Kifley A, Wang JJ, Mitchell P. Role of near work in myopia: findings in a sample of Australian school children. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49(7):2903–2910. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Garner LF, Kinnear RF, McKellar M, Klinger J, Hovander MS, Grosvenor T. Refraction and its components in Melanesian schoolchildren in Vanuatu. Am J Optom Physiol Opt. 1988;65(3):182–189. doi: 10.1097/00006324-198803000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Borchert MS, Varma R, Cotter SA, Tarczy-Hornoch K, McKean-Cowdin R, Lin JH, Wen G, Azen SP, Torres M, Tielsch JM, Friedman DS, Repka MY, Kaltz J, Ibironke J, Giordano L. Risk factors for hyperopia and myopia in preschool children the multi-ethnic pediatric eye disease and Baltimore pediatric eye disease studies. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(10):1966–1973. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Trivedi RH, Wilson ME. Biometry data from caucasian and african-american cataractous pediatric eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(10):4671–4678. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Manny RE, Fern KD, Zervas HJ, Cline GE, Scott SK, White JM, Pass AF. 1% Cyclopentolate hydrochloride: another look at the time course of cycloplegia using an objective measure of the accommodative response. Optom Vis Sci. 1993;70(8):651–665. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199308000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goss DA, Cox VD, Herrin-Lawson GA, Nielsen ED, Dolton WA. Refractive error, axial length, and height as a function of age in young myopes. Optom Vis Sci. 1990;67(5):332–338. doi: 10.1097/00006324-199005000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee KE, Klein BE, Klein R, Quandt Z, Wong TY. Association of age, stature, and education with ocular dimensions in an older white population. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(1):88–93. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2008.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.McCarthy CS, Megaw P, Devadas M, Morgan IG. Dopaminergic agents affect the ability of brief periods of normal vision to prevent form-deprivation myopia. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84(1):100–107. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pre-publication history

- The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2415/14/163/prepub