Abstract

The plant receptor kinase BAK1/SERK3 has been identified as a partner of ligand-binding leucine-rich repeat receptor kinases, in particular the brassinosteroid receptor BRI1 and the immune receptor FLS2. BAK1 positively regulates BRI1 receptor function via physical interaction and transphosphorylation. Since its first description in 2001, several independent groups have discovered BAK1/SERK3 as a component of diverse processes, including brassinosteroid signaling, light responses, cell death, and plant innate immunity. Here, we summarize current knowledge of the functional repertoire of BAK1 and discuss how its multiple functions could be integrated, how receptor complexes are potentially formed and how specificity might be determined.

BAK1/SERK3: a multifunctional protein

BAK1 (BRI1-associated kinase 1) is a leucine-rich repeat receptor-like kinase (LRR-RLK) that consists of a small extracellular LRR domain with five repeats; the first one is not fully conserved. The LRR domain is followed by a SPP motif, the serine and proline rich domain that defines the SERK protein family [1], a single membrane-spanning domain, a cytoplasmic kinase domain and a short C-terminal tail. Together with its four closest homologs, BAK1 is part of the SERK protein family, originally defined by its founding member, the somatic embryogenesis receptor kinase 1 (SERK1) and is, therefore, also called SERK3 [1]. After the identification of SERK3 as a signaling partner of another LRR-receptor kinase (LRR-RK), the brassinosteroid receptor BRI1 (Brassinosteroid Insensitive1) in 2002, SERK3 has been renamed as BAK1 for BRI1-Associated Kinase 1 [2,3]. In recent years the BRI1/BAK1 pair became one of the best-studied plant receptor models. Surprisingly, in 2005 and 2007, additional functions in light signaling [4] and in the containment of cell death [5,6] were assigned to BAK1. In addition, BAK1 was shown to interact with another ligand-binding LRR-RK, the flagellin receptor FLS2 (Flagellin Sensing 2) [7,8], which is structurally similar to BRI1 but has a function in plant innate immunity. These studies led to the hypothesis that BAK1 has a central role in the regulation of multiple LRR-RLKs and serves these various functions by interacting with different ligand-binding receptors in a stimulus-dependent manner [9–11] (Figure 1). Here we illustrate how the multiple newly identified functions of BAK1 can be integrated into the current knowledge of LRR-RLK activation and signaling.

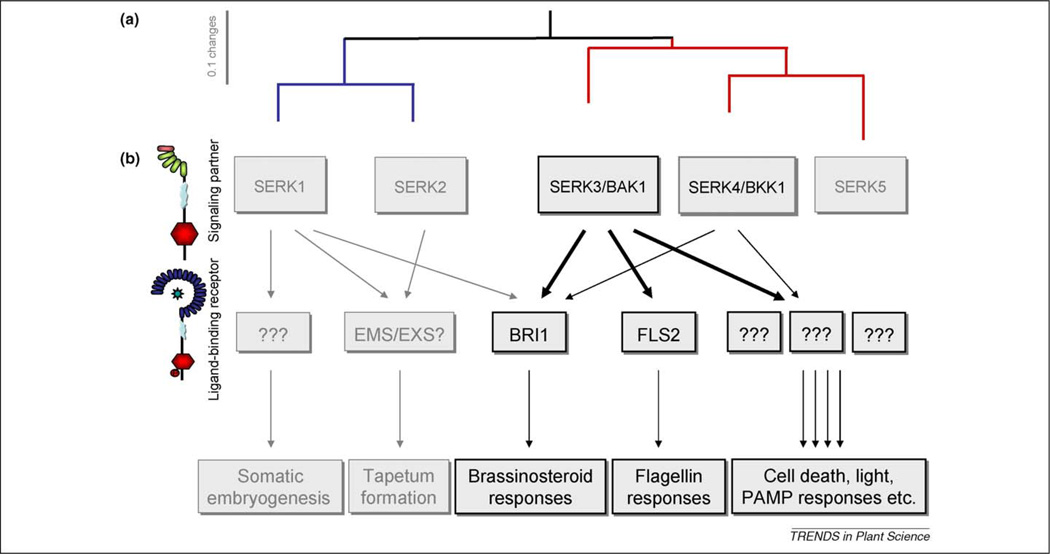

Figure 1.

The multiple functions of BAK1. (a) The phylogenetic tree of the SERK protein family indicates that SERK1 and 2 form a subgroup (blue) as well as SERK3 to 5 with SERK4 being the closest relative of BAK1 (red). The sequences were deduced from TAIR (www.arabidopsis.org) and the phylogenetic tree was generated with ClustalW. (b) Together with ligand binding receptors such as BRI1, FLS2, and additional unknown receptors (indicated by ???), BAK1 influences diverse processes such as somatic embryogenesis [1], tapetum formation [61,62], BR [2,3] and flagellin responses [7,8], cell death [5,6], light [4] and additional PAMP responses [7,8]. Some processes are synergistically influenced by more than one SERK protein, while some SERK proteins are involved in the regulation of multiple pathways [29] resulting in a complex functional network.

BAK1: the BRI1-associated kinase 1

Brassinosteroids (BRs) are involved in various developmental processes and responses to biotic and abiotic stresses [12]. BRs are perceived by the BRI1 receptor [13], and its close relatives BRI1-Like 1 (BRL1) and BRI1-Like 3 (BRL3) [14]. Several members of the SERK family, such as BAK1 [2,3], SERK1 [15] and BAK1-like Kinase 1 (BKK1), also named SERK4 [6], were identified as BRI1-interacting proteins that are probably not required for BR binding [16]. Binding of BRs to preformed BRI1 homo-oligomers results in transphosphorylation and dimer stabilization [17], hetero-oligomerization with BAK1 [18] and activation of BR signaling (Figure 2). Approximately 20% of BRI1 protein exist as homodimers in the plasma membrane in the absence of BR [19]. Transition of the homo-oligomeric BRI1 complexes into hetero-oligomeric BRI1-BAK1 complexes might require ligand-induced removal of inhibitors such as BKI1 (BRI1 Kinase Inhibitor 1) that was shown to be phosphorylated by BRI1 and dissociates from plasma membrane in response to BR [20] (Figure 2). This scenario is reminiscent to the activation process of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor ERBB1 in animals. It exists as a pre-dimerized inactive receptor complex in membranes [21]. Upon ligand binding it undergoes a conformational change and recruits ERBB2, which is a constitutively activated paralog of ERBB1, into a hetero-tetrameric complex [22]. This association is responsible for activation of the ERBB1 kinase domain and confers full responsiveness to mature EGFs [23].

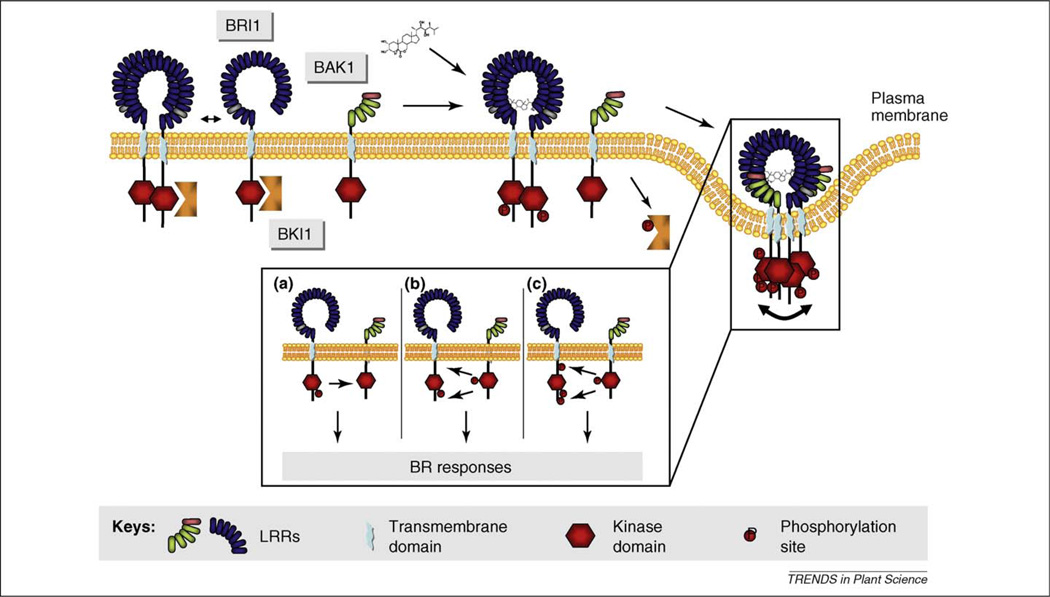

Figure 2.

Model of the BRI1/BAK1 receptor complex activation. The initial stages of BR-dependent activation of BRI1 and BAK1 are shown. BRI1 exists as a homodimer even in the absence of the ligand [19]. Upon binding of BRs autophosphorylation commences from BRI1, resulting in a basal level of signaling, even in the complete absence of BAK1 or its orthologs SERK1 and BKK1 (both not shown here for simplicity) [24]. Release of BKI1 upon phosphorylation by BRI1 allows hetero-oligomerization with BAK1 [20]. Transphosphorylation of BAK1 by BRI1 then results in enhanced BRI1/BAK1 association [24,25]. (a)–(c) The reciprocal sequential phosphorylation events are shown for half of the heterotetrameric pair. Finally, transphosphorylation of BRI1 by BAK1 may result in full activation of the BR signaling complex [24]. The resulting tetrameric complexes are internalized into endosomal compartments [32].

Based on a series of experiments sequential and reciprocal transphosphorylation between BRI1 and BAK1 was proposed [24]. In this model, BR binding induces a basal level of phosphorylation on BRI1 and, therefore, of BR signaling. This occurs even in the complete absence of BAK1 and its paralog BKK1 [24]. However, the full potential of BR signaling is effective only when BRI1 oligomerizes with BAK1 in a ligand-dependent manner. Functional analysis of phosphorylated residues identified in vivo in BRI1 and BAK1 indicates that the BRI1 receptor activates BAK1 by transphosphorylation of residues in its activation loop. In turn, BAK1 phosphorylates serine or threonine residues in the juxtamembrane and the C-terminal regions of BRI1, leading to an increase in kinase activity of the BR receptor and, therefore, full BR signaling [24] (Figure 2). Several residues in the extracellular domain and the activation loop of BAK1 have been identified that might be required for the interaction and reciprocal phosphorylation of BRI1 and BAK1 [25]. Both studies [24,25] suggest that BAK1 intensifies and prolongs BRI1-mediated signaling. Interestingly, at low concentrations of BR after brassinazole treatment, BRI1 protein stability is reduced in the bak1 bkk1 background [24]. This observation suggests a role for SERK proteins in preventing BRI1 degradation as a means to enhance BR signaling.

SERK1 is also able to interact with BRI1 [15]. In vitro binding of BRI1 and SERK1 does not require active phosphorylation by the BRI1 protein [26]. In vivo analyses will show if differences in interaction properties exist between the SERK1/BRI1 and the BAK1/BRI1 complexes. Surprisingly, in vitro BRI1 and BAK1 exhibit tyrosine phosphorylation activity that was rarely reported in plants and this activity has an important role in BRI1 function in vivo [27]. This might also be the case for BAK1 [27] and SERK1 activities [28].

An observation already made in the first reports on BAK1 [2,3] and confirmed since in other studies [17,24] is that the BR-related phenotypes are weaker when compared with bri1 null alleles. This phenomenon cannot be fully attributed to genetic redundancy with other SERK family members because the extreme dwarf cabbage phenotype of strong bri1 alleles has not been observed in any of the multiple serk mutant combinations tested. The bak1 bkk1 double mutant has a seedling lethal phenotype that is different from the bri1 cabbage phenotypes and appears to have non-BRI1-related defects [6,24,29]. No further enhancement of a BR phenotype was seen in different tested combinations of mutated SERK genes [29], while the sizes of the BRI1 complexes in vivo (250 and 400–450 kDa, respectively) are in agreement with their homodimeric and hetero-tetrameric (with BAK1 or SERK1) configurations as functional units [30].

BAK1 accelerates internalization of BRI1 by endocytosis [31], BRI1 signaling activity remains detectable after internalization [32] and inhibition of endocytosis by endosin results in bri1 mutant-like phenotypes [33]. This suggests that, as in animal cells [34], plant receptors are internalized and might continue signaling from the endosomal compartment. BAK1 is also found in complexes with FLS2 and loss of BAK1 appears to impair endocytosis of the FLS2 receptor [7]. However, the kinetics of BAK1-FLS2 interaction is different, so it remains to be determined whether the role of BAK1 in the different pathways is the same.

Taken together, a picture emerges that shows BAK1 as an adaptor and enhancer of BR signaling, probably in a tetrameric configuration withBRI1homodimers. Reciprocal and sequential phosphorylation of BAK1 and BRI1 result in stabilization of the complex and in full responsiveness to BR.

In a candidate-based screen for alterations in photo-morphogenesis, the Arabidopsis elongated (elg) mutant, originally found as a suppressor mutant of giberrellic acid-insensitive ga4 plant with elongated hypocotyl [35], was identified and mapped to the BAK1 locus [4]. The elg mutation is a semi-dominant point mutation in the third LRR of BAK1 that results in enhanced photomorphogenesis and hypersensitivity to BR [4]. Whereas the photo-morphogenic phenotype of elg is thought to be influenced by enhanced BR signaling, approaches from different directions have revealed additional functions of BAK1 which are independent from BR signaling.

BAK1: BR-independent functions

Starting from a reverse genetic approach to identify RLKs involved in Arabidopsis immunity to microbial infection, it was shown that bak1 mutants exhibit spreading necrosis after infection with bacterial and fungal pathogens [5]. The containment of stress-induced cell death is disturbed in bak1 mutant plants. Consequently, necrotrophic fungi such as Alternaria brassicicola or Botrytis cinerea show enhanced growth on bak1 mutants, whereas hemibiotrophic bacteria that do not profit from enhanced cell death do not show alterations in proliferation.

The BAK1-dependent “survival” pathway was shown to be regulated in a BR-independent manner [5]: first, exogenous application of BR results in complementation of growth defects of bak1 mutants but does not result in alteration of cell death. Second, neither BR biosynthesis mutants nor weak bri1 receptor mutant alleles show any bak1-like cell death phenotype. Finally, expression patterns obtained after pathogen and BR treatments do not show any overlap that would explain the observed bak1 phenotypes [5]. The phenotype of bak1 double mutants with its closest paralog serk4 or bkk1 further supports the role of BAK1 in cell death control [6]. These double mutants show light-dependent stress responses and seedling lethality after 10 days as a result of enhanced cell death reactions [6,36]. NbBAK1-silenced Nicotiana benthamiana plants also show enhanced cell death upon infection with the Oomycete pathogen Hyaloperonospora parasitica [8]. These results suggest BR-independent functions of BAK1 that must be regulated by a mechanism other than BAK1 interaction with the BR receptor BRI1. Further analyses have revealed additional BR-independent functions of BAK1 in plant defense against various pathogens as described below.

BAK1: a signaling partner of pattern recognition receptors

Plants use plasma membrane localized receptors called pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) to detect microbial signatures named pathogen- or microbe-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs or MAMPs) and activate the first line of innate immune responses, referred to as PAMP-triggered immunity (PTI, see Glossary). Two well-characterized PRRs in Arabidopsis are the LRR-RKs FLS2 and EFR (EF-Tu Receptor), which specifically recognize bacterial flagellin (or its active epitope flg22) and Elongation Factor Tu (or the minimal active motif elf18) [37]. The first signaling event after flagellin perception by FLS2 is probably the recruitment of BAK1 into the flagellin receptor complex [7,8]. The biological significance of this observation is corroborated by the finding that Arabidopsis and N. benthamiana plants defective in the BAK1 gene are less sensitive to flg22 treatment, in addition to the defects in BR signaling [7,8,38]. Therefore, BAK1 is also a positive regulator of PAMP signaling acting at an early step in signal transduction. Furthermore, N. benthamiana plants silenced for the BAK1 ortholog are more susceptible to adapted and non-adapted Pseudomonas and to the Oomycete H. parasitica [8]. This phenotype could not be observed in Arabidopsis bak1 mutants [5].

Similar to binding of BR to BRI1, binding of flg22 to FLS2 is independent of BAK1 function [7]. Flg22 induces rapid (~2 min) oligomerization of BAK1 and FLS2 and this lag phase is consistent with the onset of the earliest flg22-induced physiological responses. No lag phase has been defined for association of BRI1 and BAK1, which is detectable ~90 min after stimulation with BRs [18,24]. Therefore it would be helpful to refine the association analysis to compare the two BAK1-dependent receptor systems. In a hypothetical model for flagellin signaling, BAK1 might act as a signaling partner for FLS2, helping the ligand-binding receptor to transmit the flagellin signal from the outside of the cells to the inside (Box 1). Despite recent advances, the biochemical function of BAK1 and the precise mechanism underlying activation of the flagellin receptor remain unclear. In the case of BR perception, it was demonstrated that BRI1 and BAK1 are transphosphorylating in vivo [18,24]. By contrast, there is currently no direct evidence for BAK1 and FLS2 phosphorylation in response to flagellin treatment. In vitro, the FLS2 kinase domain exhibits a significant autophosphorylation activity [39] whereas quantitative phosphoproteomics did not reveal the presence of BAK1 or FLS2 among the number of plasma membrane proteins to be specifically phosphorylated in response to flg22 [40,41]. However mutagenesis of some serine and threonine residues present in BAK1 as well as FLS2 sequences showed that some are critical for functionality of these receptor kinases in flagellin signaling [24,42].

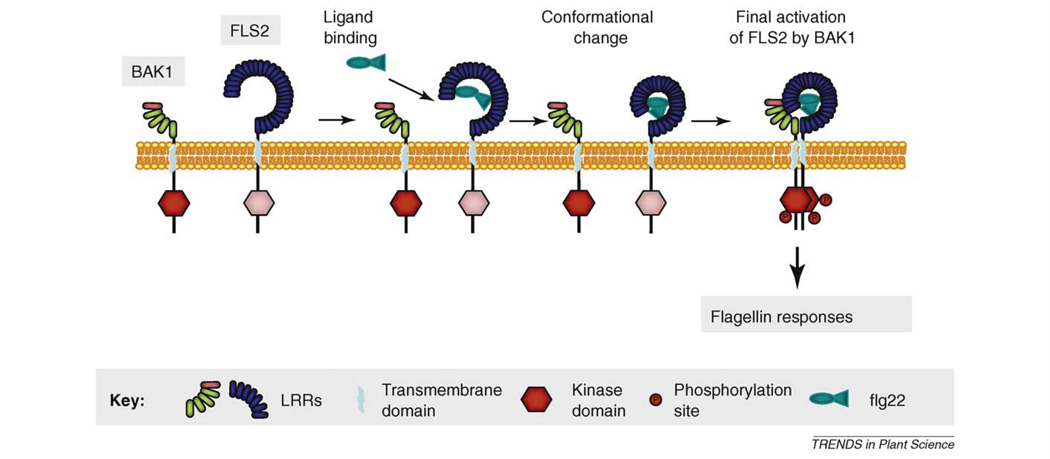

Box 1. How does BAK1 activate PRRs?

Some advances have been made on the model of flg22 perception by FLS2 which leads us to the following model including BAK1 (Figure I). In a first step the flagellin signal is perceived by FLS2 independently of BAK1 probably via binding to its LRR ectodomain [63]. At this stage BAK1 is not required. Perception of the flg22D2 peptide which binds FLS2 but acts as an antagonist of flg22, is not sufficient to induce stable oligomerization of FLS2 with BAK1. Thus, we can assume that a first step of activation of FLS2 is required which may coincide with conformational changes in the ectodomain of FLS2. These modifications might then allow association of FLS2 with BAK1. Currently our knowledge on the mechanisms of oligomerization of LRR-RKs with BAK1 is indeed very limited: it seems that BRI1 kinase activity and some critical residues in the ectodomain of BAK1 are essential for their association but the exact domains involved in this interaction are unknown [24,25]. In the case of FLS2, the rapid oligomerization of FLS2 with BAK1 may indicate a pre-association of FLS2 and BAK1 in the plasma membrane even before perception of the ligand. Despite this close proximity, the complex may be stabilized and thus detectable in co-immunoprecipitation assays only after ligand perception [7]. As a consequence of interaction between the ectodomains of FLS2 and BAK1 the interaction of their kinase domains in the cytoplasm may then occur as a last step of receptor activation to promote subsequent trans-phosphorylation events and initiation of a defense program in the cytoplasm.

Figure I. A model for activation of FLS2 by BAK1. This model illustrates the first steps of activation of the flagellin receptor, based on models of animal receptor kinases [23] and our current knowledge on the FLS2 receptor. At least three steps can be predicted: first the exogenous signal flg22 binds to the ectodomain of FLS2 (step 1), which may induce some conformational changes of FLS2 (step 2). In this second conformation FLS2 can associate with its partner BAK1 to finally activate a signaling pathway in the cytoplasm (step 3).

The residual sensitivity to flg22 observed for the bak1 null mutants is intriguing and raises the question of functional redundancy between BAK1 and the other SERK members in PAMP signaling. However, serk single mutants other than bak1 do not show any phenotype in response to flg22 treatment [7,8]. Further genetic analysis with double and multiple mutants might reveal the involvement of additional SERK proteins in flg22 signaling.

Activation of FLS2 and EFR upon PAMP perception initiates common signaling pathways [43]. The convergent point might be BAK1 because it is required for multiple PRR signaling pathways in Arabidopsis, including the EFR pathway [7,38]. Nicotiana benthamiana BAK1-silenced plants are also affected in responses to the bacterial cold shock protein and the Phytophtora infestans elicitor INF1 [8]. Finally, bak1-deficient plants display altered disease susceptibility to several pathogens, including bacteria, Oomycetes (in N. benthamiana) and necrotrophic fungi (Arabidopsis) [5,8]. Therefore it is likely that BAK1 interacts with, and regulates the activity of PRRs other than FLS2, although this is not yet supported by any biochemical evidence. Conversely, some PTI pathways are independent of BAK1 function, such as the fungal chitin signaling pathway in Arabidopsis [8,44]. Instead, chitin signaling is initiated by the LysM-receptor kinase CERK1, which leads to fungal resistance [45,46]. Recently, it was found that CERK1 was also required for PTI to bacterial pathogens [44]. It is proposed that CERK1 acts as a regulator of another subset of PRRs, analogous to the function of BAK1 with FLS2 and other PRR.

Immunity in plants not only involves PTI, but also a race-cultivar-specific effector-triggered immunity (ETI, see Glossary). Recently, a function of a BAK1 ortholog was assigned in race-specific resistance of Solanum lycopersicum to the fungus Verticillium dahliae, which is mediated by the receptor-like protein Ve1. Tomato plants silenced for the N. benthamiana-derived BAK1 sequence showed more susceptibility to Verticillium infection. This suggests either a direct or indirect effect of BAK1 on Ve1-mediated resistance [47]. Moreover, the Arabidopsis BIR1 RLK was identified as a BAK1-interacting receptor-like kinase [48]. Mutants affected in BIR1 show a strong cell death phenotype and constitutive activation of defense responses. BIR1 also interacts with the SOBIR RLK, a protein identified as a suppressor of the bir1 phenotype, which activates cell death and defense responses [48]. This suggests that BIR1 acts as a negative regulator of two distinct plant resistance signaling pathways.

BAK1: a target of bacterial effectors

Virulent pathogens have evolved highly sophisticated mechanisms to infect their hosts. Many Gram-negative bacteria of plant and animal pathogens inject a range of effector proteins into host cells through the type III secretion system (see Glossary). A key function of effectors is to modulate diverse host cellular activities and block defense responses [49–51]. It has been shown that several effectors target important steps in PAMP perception and signaling to impede plant innate immunity [37,49–51]. Two functionally related but sequence distinct effectors, AvrPto and AvrPtoB, from a ubiquitous plant pathogen Pseudomonas syringae, suppress the convergent defense signaling stimulated by flg22 and some other PAMPs upstream of a MAP kinase cascade [52–54]. In light of its plasma membrane localization in plant cells, AvrPto was speculated to associate with PAMP receptors, such as the membrane-localized flagellin receptor FLS2 [42]. Indeed, AvrPto was shown to interact with FLS2 and EFR when overexpressed in Arabidopsis protoplasts [55]. Intriguingly, transgenic plants expressing AvrPto driven by the CaMV 35S promotor display BR-insensitive phenotypes. This observation led to a seminal finding that AvrPto and AvrPtoB directly target BAK1, and interfere with the formation of FLS2/BAK1 and BRI1/BAK1 complexes [38]. By targeting BAK1, a common component involved in multiple PAMP signaling, BR signaling and cell death control, bacterial effectors parsimoniously modulate diverse host cellular activities for the benefit of pathogen infection. It appears that AvrPto also targets BAK1-independent signaling pathways, given that BAK1 functions in a subset of PAMP-responses, whereas AvrPto is equally effective in suppressing the immune responses triggered by all PAMPs tested [38]. That AvrPto is not acting in a BAK1 specific way gains further support from the observation that AvrPto associates with at least two additional SERK family members, SERK4 and SERK5 [38]. The roles of SERK4 and SERK5 in plant PTI are yet to be determined.

The second BAK1-interacting effector protein AvrPtoB is a modular protein with two distinct domains. The N-terminus of AvrPtoB has similar PAMP suppression function as AvrPto, whereas the C-terminus displays structural similarity to the U box and RING finger components of E3 ubiquitin ligases [56]. Although its ubiquitin ligase activity appears not to be essential for its flg22 suppression function, AvrPtoB ubiquitinates and targets FLS2, but not BAK1 for degradation in vivo and in vitro [51]. AvrPtoB also ubiquitinates the kinase domain of CERK1 [44,46]. In addition to effectors from P. syringae, the effector protein DspA/E from the necrotrophic bacterial pathogen Erwinia amylovora interacts with several RLKs [57], and XopN from Xanthomonas interacts with a tomato atypical RLK and suppresses PTI [58]. A viral effector protein has also been reported to interact with RLKs [59]. All these targeted RLKs have characteristic small extracellular domains similar to BAK1. It might be that targeting this type of RLKs is a general strategy deployed by pathogens to block the initiation of defense signaling.

What will the future bring?

Our current knowledge of the repertoire of receptors regulated by BAK1 is probably just the tip of the iceberg (Figure 1). For the known pathways it was shown that BAK1 does not bind ligands as BR or flg22 itself, but it cannot be completely excluded that BAK1 might bind other ligands. The fact that several defense, cell death and light pathways independent of flagellin or BR signaling are affected by the BAK1 mutation suggest that BAK1 interacts with a range of receptors other than BRI1 and FLS2. How do plants regulate this common signaling component, particularly given that several of the pathways must be active in the same cells? Is internalization of BAK1 together with a ligand binding receptor necessary for signaling in one pathway and not in the others? Is there competition among the pathways? Although there is no overlap of gene expression or responses, it is interesting that flg22 treatment induces growth inhibition of Arabidopsis seedlings, which might suggest a competition effect between the flagellin and the BR pathways mediated by BAK1. Are there additional regulatory components necessary to direct BAK1 into its respective pathways? Currently, it is not known how the receptor complexes are formed. Accumulation of BAK1 in special membrane compartments might assure a close vicinity to its ligand-binding receptors [60] or preformed inactive complexes as suggested for the EGF receptor from animals. The finding of ligand-induced association of BAK1 with ligand binding receptors does not exclude the existence of pre-formed complexes in the plant membrane: in absence of ligand these complexes might be unstable and therefore not detectable by biochemical methods. Such close vicinity between receptor elements might allow rapid activation of the receptors. But it is also possible that the signaling partners are freely moving in the membrane and are only recruited after ligand binding to the activated complexes. How is signal specificity achieved downstream of the receptor complexes? In one scenario, the specificity determining signal is provided by the ligand binding receptor itself rather than by BAK1. This would fit with a model in which BAK1 acts as an enhancer for several LRR-RKs as shown for BRI1 [24] rather than a signal transducer that regulates downstream components. By contrast, phosphorylation of BAK1 threonine residue 450 was shown to be essential for flg22 and BR signaling but seems to be dispensable for cell death complementation [24]. This supports another model for BAK1 function. Differential phosphorylation of BAK1 by the signal-specific ligand-binding receptor might determine the specificity of downstream signaling. Given that events immediately downstream of the receptor complex remain to be elucidated in both known pathways, further studies are needed to clarify how specificity is achieved.

The weak phenotypes of bak1-mutants compared with the main or ligand-binding receptor mutants suggest either redundancy with other proteins or an additive, signal enhancing function of BAK1, as proposed for BR signaling [24]. For the cell death pathway, BKK1 was shown to act synergistically with its closest paralog BAK1, resulting in severe phenotypes in the double mutants [6]. No additional effects could be observed with the tested serk mutants in BR and cell death responses. The significance of BAK1 in the other pathways remains to be analyzed as does whether additional (even non-SERK family) signaling partners are involved in other BAK1-dependent signaling events.

Identification of the whole functional repertoire of BAK1 and its ligand-binding receptors will help to clarify how BAK1 contributes to signal transduction over the plasma membrane. Given the different kinetics of FLS2/BAK1 and BRI1/BAK1 assembly, different strategies are conceivable. Interaction studies with the ligand-binding receptors, their signaling partners and additional components and time resolution and competition analyses will help to address these questions.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Cyril Zipfel, Thomas Boller and Thorsten Nürnberger for critical discussions and helpful comments on the manuscript.

Glossary

- Effector proteins

microbial proteins that are secreted into the host cells and promote infection

- ETI

effector-triggered immunity, race/cultivar-specific resistance based on the perception of effector proteins or modifications of effector targets by resistance proteins and that leads to a quick and strong induction of specific defense responses

- PAMP or MAMP

pathogen or microbe-associated molecular pattern, conserved (surface) structures of pathogens or microbes that are recognized but not present in the host, term also used in animal innate immunity

- PRR

pattern recognition receptors, receptor proteins that can perceive PAMPs and trigger innate immunity in plants and animals

- PTI

PAMP-triggered immunity, basal defense mechanism effective against a broad range of pathogens induced after PAMP perception

- Type-III secretion system

a specialized protein secretion system found only in Gram-negative bacteria, through which a set of proteins can be delivered directly from the bacterial cells into the host cells

References

- 1.Hecht V, et al. The Arabidopsis SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR KINASE 1 gene is expressed in developing ovules and embryos and enhances embryogenic competence in culture. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:803–816. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li J, et al. BAK1, an Arabidopsis LRR receptor-like protein kinase, interacts with BRI1 and modulates brassinosteroid signaling. Cell. 2002;110:213–222. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00812-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nam KH, Li J. BRI1/BAK1, a receptor kinase pair mediating brassinosteroid signaling. Cell. 2002;110:203–212. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00814-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whippo CW, Hangarter RP. A brassinosteroid-hypersensitive mutant of BAK1 indicates that a convergence of photomorphogenic and hormonal signaling modulates phototropism. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:448–457. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.064444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kemmerling B, et al. The BRI1-associated kinase 1, BAK1, has a brassinolide-independent role in plant cell-death control. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:1116–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He K, et al. BAK1 and BKK1 regulate brassinosteroid-dependent growth and brassinosteroid-independent cell-death pathways. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:1109–1115. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chinchilla D, et al. A flagellin-induced complex of the receptor FLS2 and BAK1 initiates plant defence. Nature. 2007;448:497–500. doi: 10.1038/nature05999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heese A, et al. The receptor-like kinase SERK3/BAK1 is a central regulator of innate immunity in plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:12217–12222. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705306104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kemmerling B, Nürnberger T. Brassinosteroid-independent functions of the BRI1-associated kinase BAK1/SERK3. Plant Signal. Behav. 2008;3:116–118. doi: 10.4161/psb.3.2.4981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ingram GC. Cell signalling: the merry lives of BAK1. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:603–605. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vert G. Plant signaling: brassinosteroids, immunity and effectors are BAK! Curr. Biol. 2008;18:963–965. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clouse SD, Sasse JM. BRASSINOSTEROIDS: Essential Regulators of Plant Growth and Development. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 1998;49:427–451. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.49.1.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Chory J. A putative leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase involved in brassinosteroid signal transduction. Cell. 1997;90:929–938. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cano-Delgado A, et al. BRL1 and BRL3 are novel brassinosteroid receptors that function in vascular differentiation in Arabidopsis. Development. 2004;131:5341–5351. doi: 10.1242/dev.01403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karlova R, et al. The Arabidopsis SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASE1 protein complex includes BRASSINOSTEROID-INSENSITIVE1. Plant Cell. 2006;18:626–638. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.039412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinoshita T, et al. Binding of brassinosteroids to the extracellular domain of plant receptor kinase BRI1. Nature. 2005;433:167–171. doi: 10.1038/nature03227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang X, et al. Autoregulation and homodimerization are involved in the activation of the plant steroid receptor BRI1. Dev. Cell. 2005;8:855–865. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang X, et al. Identification and functional analysis of in vivo phosphorylation sites of the Arabidopsis BRASSINOSTEROID-INSENSITIVE1 receptor kinase. Plant Cell. 2005;17:1685–1703. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.031393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hink MA, et al. Fluorescence fluctuation analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana somatic embryogenesis receptor-like kinase and brassinosteroid insensitive 1 receptor oligomerization. Biophys. J. 2008;94:1052–1062. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.112003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X, Chory J. Brassinosteroids regulate dissociation of BKI1, a negative regulator of BRI1 signaling, from the plasma membrane. Science. 2006;313:1118–1122. doi: 10.1126/science.1127593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gadella TW, Jr, Jovin TM. Oligomerization of epidermal growth factor receptors on A431 cells studied by time-resolved fluorescence imaging microscopy. A stereochemical model for tyrosine kinase receptor activation. J. Cell. Biol. 1995;129:1543–1558. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.6.1543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ward CW, et al. The insulin and EGF receptor structures: new insights into ligand-induced receptor activation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2007;32:129–137. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Citri A, Yarden Y. EGF-ERBB signalling: towards the systems level. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:505–516. doi: 10.1038/nrm1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang X, et al. Sequential transphosphorylation of the BRI1/BAK1 receptor kinase complex impacts early events in brassinosteroid signaling. Dev. Cell. 2008;15:220–235. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yun HS, et al. Analysis of phosphorylation of the BRI1/BAK1 complex in Arabidopsis reveals amino acid residues critical for receptor formation and activation of BR signaling. Mol. Cells. 2009;27:183–190. doi: 10.1007/s10059-009-0023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karlova R, et al. Identification of in vitro phosphorylation sites in the Arabidopsis thaliana somatic embryogenesis receptor-like kinases. Proteomics. 2009;9:368–379. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200701059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oh MH, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the BRI1 receptor kinase emerges as a component of brassinosteroid signaling in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:658–663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810249106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shah K, et al. Expression of the Daucus carota somatic embryogenesis receptor kinase (DcSERK) protein in insect cells. Biochimie. 2001;83:415–421. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(01)01257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Albrecht C, et al. Arabidopsis SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR KINASE proteins serve brassinosteroid-dependent and - independent signaling pathways. Plant Physiol. 2008;148:611–619. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.123216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karlova R, de Vries SC. Advances in understanding brassinosteroid signaling. Sci. STKE. 2006;2006:36. doi: 10.1126/stke.3542006pe36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russinova E, et al. Heterodimerization and endocytosis of Arabidopsis brassinosteroid receptors BRI1 and AtSERK3 (BAK1) Plant Cell. 2004;16:3216–3229. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.025387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geldner N, et al. Endosomal signaling of plant steroid receptor kinase BRI1. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1598–1602. doi: 10.1101/gad.1561307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robert S, et al. Endosidin1 defines a compartment involved in endocytosis of the brassinosteroid receptor BRI1 and the auxin transporters PIN2 and AUX1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:8464–8469. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711650105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miaczynska M, et al. Not just a sink: endosomes in control of signal transduction. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2004;16:400–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halliday K, et al. The ELONGATED gene of Arabidopsis acts independently of light and gibberellins in the control of elongation growth. Plant. J. 1996;9:305–312. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1996.09030305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He K, et al. Receptor-like protein kinases, BAK1 and BKK1, regulate a light-dependent cell-death control pathway. Plant Signal. Behav. 2008;3:813–815. doi: 10.4161/psb.3.10.5890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boller T, Felix G. A renaissance of elicitors: perception of microbe-associated molecular patterns and danger signals by pattern-recognition receptors. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2009;60:379–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shan L, et al. Bacterial effectors target the common signaling partner BAK1 to disrupt multiple MAMP receptor-signaling complexes and impede plant immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:17–27. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gomez-Gomez L, et al. Both the extracellular leucine-rich repeat domain and the kinase activity of FSL2 are required for flagellin binding and signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2001;13:1155–1163. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Benschop JJ, et al. Quantitative phosphoproteomics of early elicitor signaling in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:1198–1214. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600429-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nühse TS, et al. Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of plasma membrane proteins reveals regulatory mechanisms of plant innate immune responses. Plant. J. 2007;51:931–940. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03192.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robatzek S, et al. Ligand-induced endocytosis of the pattern recognition receptor FLS2 in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:537–542. doi: 10.1101/gad.366506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zipfel C, et al. Perception of the bacterial PAMP EF-Tu by the receptor EFR restricts Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Cell. 2006;125:749–760. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gimenez-Ibanez S, et al. AvrPtoB targets the LysM receptor kinase CERK1 to promote bacterial virulence on plants. Curr. Biol. 2009;19:423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wan J, et al. A LysM receptor-like kinase plays a critical role in chitin signaling and fungal resistance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2008;20:471–481. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.056754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miya A, et al. CERK1, a LysM receptor kinase, is essential for chitin elicitor signaling in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:19613–19618. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705147104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fradin EF, et al. Genetic dissection of verticillium wilt resistance mediated by tomato Ve1. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:320–332. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.136762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gao M, et al. Regulation of cell death and innate immunity by two receptor-like kinases in Arabidopsis. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;6:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Block A, et al. Phytopathogen type III effector weaponry and their plant targets. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2008;11:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Speth EB, et al. Pathogen virulence factors as molecular probes of basic plant cellular functions. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2007;10:580–586. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Göhre V, et al. Plant pattern-recognition receptor FLS2 is directed for degradation by the bacterial ubiquitin ligase AvrPtoB. Curr. Biol. 2008;18:1824–1832. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Torres M, et al. Pseudomonas syringae effector AvrPtoB suppresses basal defence in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2006;47:368–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hann DR, Rathjen JP. Early events in the pathogenicity of Pseudomonas syringae on Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant J. 2007;49:607–618. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.He P, et al. Specific bacterial suppressors of MAMP signaling upstream of MAPKKK in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Cell. 2006;125:563–575. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiang T, et al. Pseudomonas syringae effector AvrPto blocks innate immunity by targeting receptor kinases. Curr. Biol. 2008;18:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Janjusevic R, et al. A bacterial inhibitor of host programmed cell death defenses is an E3 ubiquitin ligase. Science. 2006;311:222–226. doi: 10.1126/science.1120131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meng X, et al. Apple proteins that interact with DspA/E, a pathogenicity effector of, the fire blight pathogen. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2006;19:53–61. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kim JG, et al. Xanthomonas T3S Effector XopN suppresses PAMP-triggered immunity and interacts with a tomato atypical receptor-like kinase and TFT1. Plant Cell. 2009;21(4):1305–1323. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.063123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fontes EP, et al. The geminivirus nuclear shuttle protein is a virulence factor that suppresses transmembrane receptor kinase activity. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2545–2556. doi: 10.1101/gad.1245904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zappel NF, Panstruga R. Heterogeneity and lateral compartmentalization of plant plasma membranes. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2008;11:632–640. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Albrecht C, et al. The Arabidopsis thaliana SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR-LIKE KINASES1 and 2 control male sporogenesis. Plant Cell. 2005;17:3337–3349. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.036814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Colcombet J, et al. Arabidopsis SOMATIC EMBRYOGENESIS RECEPTOR KINASES1 and 2 are essential for tapetum development and microspore maturation. Plant Cell. 2005;17:3350–3361. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.036731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chinchilla D, et al. The Arabidopsis receptor kinase FLS2 binds flg22 and determines the specificity of flagellin perception. Plant Cell. 2006;18:465–476. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.036574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]