The authors reviewed the efficacy and toxicity of erlotinib, gefitinib, and afatinib in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Gefitinib showed activity and toxicity similar to erlotinib. Afatinib showed similar efficacy to erlotinib and gefitinib in first-line treatment of tumors harboring epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations but may be associated with more toxicity. Gefitinib deserves consideration for U.S. marketing as a primary treatment for EGFR-mutant NSCLC.

Keywords: Gefitinib, Erlotinib, Afatinib, Lung cancer, Tyrosine kinase inhibitors

Abstract

Background.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) have been evaluated in patients with metastatic and advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The U.S. Food and Drug Administration initially granted accelerated approval to gefitinib but subsequently rescinded the authorization. Erlotinib and afatinib are similar compounds approved for the treatment of metastatic NSCLC. The objective of this study was to compare the efficacy and toxicity of erlotinib, gefitinib, and afatinib in NSCLC.

Methods.

We tabulated efficacy variables including overall response rate (ORR), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS) and quantitated toxicities and rates of dose reductions and discontinuation. Summary odds ratios were calculated using random and fixed-effects models. An odds ratio was the summary measure used for pooling of studies.

Results.

We examined 28 studies including three randomized trials with afatinib. Clinical toxicities, including pruritus, rash, anorexia, diarrhea, nausea, fatigue, mucositis, paronychia, and anemia, were similar between erlotinib and gefitinib, although some statistical differences were observed. Afatinib treatment resulted in more diarrhea, rash, and paronychia compared with erlotinib and gefitinib. Regarding efficacy, similar outcomes were recorded for ORR, PFS, or OS in the total population and in specific subgroups of patients between erlotinib and gefitinib. All three TKIs demonstrated higher ORRs in first line in tumors harboring EGFR mutations.

Conclusion.

Gefitinib has similar activity and toxicity compared with erlotinib and offers a valuable alternative to patients with NSCLC. Afatinib has similar efficacy compared with erlotinib and gefitinib in first-line treatment of tumors harboring EGFR mutations but may be associated with more toxicity, although further studies are needed. Gefitinib deserves consideration for U.S. marketing as a primary treatment for EGFR-mutant NSCLC.

Implications for Practice:

EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors are valuable agents for a subset of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). We demonstrated that erlotinib and gefitinib have similar activity in patients with NSCLC and similar toxicity profiles, with a suggestion of better tolerability for gefitinib. The analysis suggests that gefitinib provides a valuable alternative for the treatment of NSCLC for the same indications as erlotinib and afatinib.

Introduction

The American Cancer Society estimates that in 2014 in the U.S., 224,210 persons will be diagnosed with lung cancer and 159,260 will die of this disease [1]. The overall 5-year survival rate measured by the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program in the U.S. is 16.8% [2]. Treatment for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the most common histological subtype, is based on staging and usually consists of surgery, radiation, platinum-based chemotherapy, and, in selected patients, tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [3–5]. The latter were initially examined in all patients but eventually were developed for patients whose tumors harbored specific mutations in the receptor [6–10].

Gefitinib (Iressa; AstraZeneca, London, U.K., http://www.astrazeneca.com) was the first oral epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) TKI approved in the U.S. In May 2003, gefitinib was granted accelerated approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on the basis of the response rate observed in 142 patients with NSCLC whose tumors were considered refractory to both docetaxel and a platinum agent [11]. Following this approval, a larger phase III trial designated Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer (ISEL) was undertaken [12]. Requested by the FDA as a postmarketing trial, the study randomized 1,129 patients refractory or intolerant to the last chemotherapy to best supportive care plus either gefitinib or placebo. Unfortunately, the trial was begun prior to the emergence of studies, discussed in this review, showing excellent responses in NSCLC harboring mutant EGFRs and was completed 4 years later, when it was clear that EGFR status determined response. The data showed a statistically significant improvement in overall response rate (ORR), but gefitinib failed to prolong the median overall survival (OS) of the study population (5.6 vs. 5.1 months for gefitinib and placebo, respectively; hazard ratio [HR]: 0.89; p = .11]. Although prospective subgroup analyses suggested survival benefits in patients of Asian origin and in those who never smoked, gefitinib did not prolong the OS of patients with adenocarcinoma, which was emerging at that time as a subset more likely to benefit from TKIs targeting EGFR [12]. Consequently, in June 2005, the FDA rescinded gefitinib’s approval, limiting its availability under the Iressa Access Program to patients benefiting from gefitinib and enrolled in clinical trials approved by an institutional review board prior to June 17, 2005 [13]. In second-line treatment, gefitinib had also been compared with docetaxel in a noninferiority trial (INTEREST) in which gefitinib met predefined noninferiority criteria, with median OS values of 7.6 and 8.0 months for gefitinib and docetaxel, respectively (HR: 1.02; p = .62) [14]. Unfortunately, as discussed in this review, the importance of sensitizing EGFR mutations had not yet become apparent—a fact that, in retrospect, helps explain this outcome.

Erlotinib, the second EGFR TKI evaluated in NSCLC, was approved by the FDA in November 2004 based on results of the BR.21 trial conducted by the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group [15, 16]. In this study, patients with advanced NSCLC were randomized to erlotinib or placebo in second- or third-line treatment. Median overall survival was 6.7 and 4.7 months for erlotinib and placebo, respectively (HR: 0.70; p < .001). Indications for erlotinib in NSCLC were subsequently extended in 2010 based on the SATURN trial, which demonstrated improved survival in patients receiving maintenance erlotinib after induction chemotherapy [17]. Consequently, in the U.S., erlotinib is currently approved as maintenance therapy of locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC in patients whose disease has not progressed after platinum-based induction chemotherapy and as a single agent in second or third line after failure of a prior platinum-based chemotherapy [18].

In 2004, two landmark publications reported somatic mutations in EGFR that predicted sensitivity and response to gefitinib [19, 20]. Subsequently, similar mutations were identified as important in the response of tumors to erlotinib, leading to the emergence of a paradigm in which the patients most likely to benefit from these therapies are those whose tumors harbor activating EGFR mutations. The presence of these mutations was reportedly increased in specific NSCLC populations, including women, patients of Asian origin, and patients without a history of smoking. Importantly, retrospective analyses had identified these subgroups as those most likely to benefit from gefitinib and erlotinib [12, 16, 21, 22]. In comparison, tumors lacking these mutations responded poorly or not at all and had marginal benefits at best in subset analyses.

Based on these findings, gefitinib was tested in specific patient populations. The phase III IPASS trial compared gefitinib with doublet chemotherapy in the first-line setting and found longer progression-free survival (PFS) with gefitinib, especially in the 60% of patients whose tumors harbored EGFR mutations (p < .001; HR: 0.48) [7]. Interestingly, in the subgroup without mutations, PFS was shorter with gefitinib than with chemotherapy (p < .001; HR: 2.85). Following the IPASS trial, four additional phase III trials compared a platinum doublet with gefitinib or erlotinib in patients whose tumors harbored EGRF mutations. All demonstrated longer PFS values in patients receiving the TKI, with PFS values of 10.8 and 9.8 months in two trials conducted in Japan using gefitinib and 9.7 and 13.1 months in a European and a Chinese study, respectively, using erlotinib [23–26].

Although not approved in the U.S., gefitinib was approved in 36 countries by 2005. In Asia, gefitinib was approved in 2005 for second- and third-line therapy. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved gefitinib in 2009 for use in locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC with activating EGFR mutations. Erlotinib received FDA approval for this last indication in 2013. At the present time in 2015, gefitinib is approved in 66 countries.

In July and September 2013, the FDA and then the EMA approved afatinib, an irreversible inhibitor of EGFR, HER2, and HER4, for the treatment of NSCLC harboring exon 19 deletions or exon 21 (L858R) mutations. The results of LUX-3, a phase III trial that compared afatinib with chemotherapy in the first-line setting, provided support for approval [27]. Envisioned as an agent that would circumvent resistance to the reversible EGFR inhibitors, principally in tumors with acquired T790M mutations, afatinib has also been evaluated in first-line settings. Although it has been argued that “the benefit compared with existing reversible EGFR TKIs is likely to be slight, if there is one at all” [28], final conclusions regarding afatinib will be easier to reach when additional data are available. Ongoing trials (NCT01466660; NCT01523587) comparing afatinib with gefitinib or erlotinib will likely provide answers as to which drug is better or whether they are similar and, equally important, will better examine the relative toxicities.

In this paper, we reviewed published data amassed worldwide for both erlotinib and gefitinib, together with three randomized studies published with afatinib, to compare their toxicity and efficacy. Although others have previously compared erlotinib and gefitinib, the emphasis has been on efficacy, often in specific subsets and frequently looking at publications that reported data gathered retrospectively [26, 29–35]. We wanted to examine subsets in greater detail, to confine the analysis to prospectively randomized clinical trials, and, most important, to query tolerability more thoroughly. No previous meta-analysis or extensive review has, for example, examined grade 1–2 toxicity. For oral agents administered daily and that are proposed as maintenance therapies, grade 1–2 toxicities are very important, driving tolerability and quality of life. Surprisingly, even grade 3–4 adverse events (AEs) have been largely ignored because the emphasis has been on efficacy. We concluded that gefitinib and erlotinib have comparable tolerability and clinical activity and that gefitinib offers a valuable treatment alternative. The role of afatinib remains to be better defined, and its advantage, if any, still must be demonstrated.

Methods

Data Sources and Selection of the Studies

Identification of relevant studies was performed by manually searching the following databases: PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Embase, Cochrane Library, CINAHL Plus, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers conference proceedings, and OAIster. Articles published between January 2003 and December 2012 were screened with the following search terms: lung AND (neoplasms OR cancer OR malignancy) AND (erlotinib OR gefitinib) AND (controlled AND clinical trial). We selected all randomized studies of erlotinib or gefitinib as treatment of advanced or metastatic stage IIIB or IV NSCLC according to the sixth American Joint Committee on Cancer classification. The following study selection criteria were used: phase II and phase III randomized studies of erlotinib or gefitinib in which the treatment arm receiving the EGFR TKI had >40 patients; the primary endpoint was PFS or OS; the total and grade 3–4 toxicities were reported; and the control arm did not receive erlotinib, gefitinib, or any other TKI. We also included in the analysis three published randomized trials of afatinib in metastatic NSCLC. A formal systematic search for this drug was not done; the studies published with afatinib in NSCLC are well known and were published in the past 3 years [27, 36, 37].

Data Extraction and Clinical Endpoints

All trials were independently reviewed by two of the study authors (M.B., E.E.M.). For each trial that met inclusion criteria, the following data were abstracted: first author’s last name; publication year; phase of the trial; sample size; experimental and control-arm treatment; ethnicity of the study population (Asian or non-Asian); participant age and sex, histology, and EGFR mutation; ORR including partial and complete responses as percentages; and PFS and OS HRs with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs), as available. For measures of tolerability, we recorded the rates of treatment discontinuation and dose reduction. For measures of toxicity, we extracted AEs, including AE leading to death and an additional 13 AEs for which we tabulated the total, and grade 1–4 toxicities including dry skin, pruritus, rash acne, anorexia, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, interstitial lung disease (ILD), anemia, transaminitis, paronychia, and stomatitis. We summed grade 1–2 and grade 3–4 AEs. Each entry in the data set consisted of an experimental arm alone, in cases for which there was no control arm, or compared with a control arm. Only entries with data in both control and experimental arms were used in meta-analyses. If there was more than one experimental or control arm in a randomized study, each unique combination of experimental and control arms was entered separately.

Statistical Analysis

Fixed- and random-effects meta-analyses using inverse variance weighting for pooling and an odds ratio (OR) as the summary measure were done for AE and ORR data using event counts and total sample size in each arm as input and for OS and PFS data using log-HR and SE as input. Meta-analyses were stratified by experimental-arm treatment (erlotinib 150 mg, gefitinib 250 mg, and afatinib 50 mg [36] and 40 mg [27, 37]). AE meta-analyses were done separately for each combination of AE and grade (grades 1–2 and 3–4). To address zero cell counts in the AE and ORR outcomes, an increment of 0.5 was added to each cell frequency of all studies, regardless of cells with counts of zero. AE and ORR data reported as <1% were assigned a value of 0.5%, whereas data reported as <3% were assigned a value of 2.5%. Response counts were calculated as response rate times the number of patients receiving the therapy, and AE counts were calculated as percentage of AE times the number of patients receiving the therapy. Because studies do not report the SE accompanying a hazard ratio, the errors needed for respective effect sizes in the OS and PFS outcomes (ln[HR]) were determined from the HR CI, from which the SE was calculated as (ln[UCI] − ln[LCI]) × 3.92 for 95% CI and (ln[UCI] − ln[LCI]) / 3.29 for 90% CI where UCI is the upper confidence interval and LCI is the lower confidence interval. Statistical heterogeneity was determined by the chi-square test. Tests for funnel plot asymmetry were performed only if the number of studies was ≥10. In the score method, which was used to test funnel plot asymmetry, the test statistic is based on a weighted linear regression that uses efficient score and score variance. All meta-analyses and forest plots, annotated with heterogeneity information, were generated using R statistical software (R version 2.15.3; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, http://www.r-project.org) and the R packages meta [38] and metafor [39].

Distribution comparisons between studies of erlotinib 150 mg and gefitinib 250 mg were done using a two-sided Wilcoxon test for the proportion of events among control arms (for each combination of AE and grade) and for median OS and PFS in experimental arms within the overall data set and the following study subpopulations: nonselected monotherapy first line, maintenance or consolidation with either gefitinib or erlotinib in first line, monotherapy second line, mutation positive EGFR and elderly populations. These analyses and the accompanying graphics were generated using R statistical software.

Data Synthesis and Assessment of Study Quality and Bias

Two study authors (M.B., T.F.) assessed trials meeting inclusion criteria for quality and bias. Disagreements between authors with respect to quality or bias scores were resolved by consensus. Jadad scale criteria were applied to assess for quality.

Results

Literature Search and Selection of Trials

The database search yielded 280 publications, which were curated as detailed above. After the selection process and application of our eligibility criteria, 28 erlotinib and gefitinib studies were subjected to meta-analysis (PRISMA flow diagram is shown in supplemental online Fig. 1). As noted, the formal literature search did not include the afatinib studies.

Quality of the Studies and Publication Bias

All 28 erlotinib and gefitinib studies meeting the inclusion criteria were randomized phase II/III trials. Twelve studies administered erlotinib, whereas 16 evaluated gefitinib. These trials had median/mean Jadad scores of 3/3.5 and 3/3 for gefitinib and erlotinib, respectively (supplemental online Fig. 2). Examination of funnel plots and the estimated degree of funnel plot asymmetry did not indicate major evidence of reporting or publication bias (supplemental online Appendix 1).

Study Characteristics

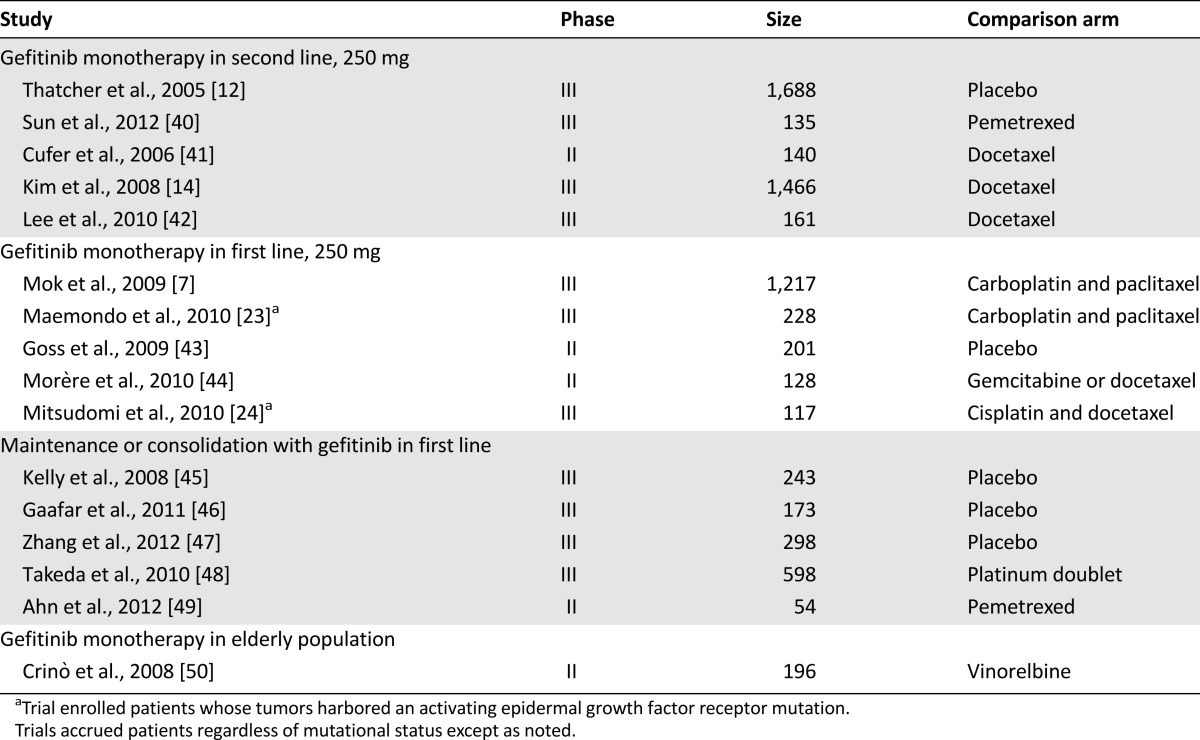

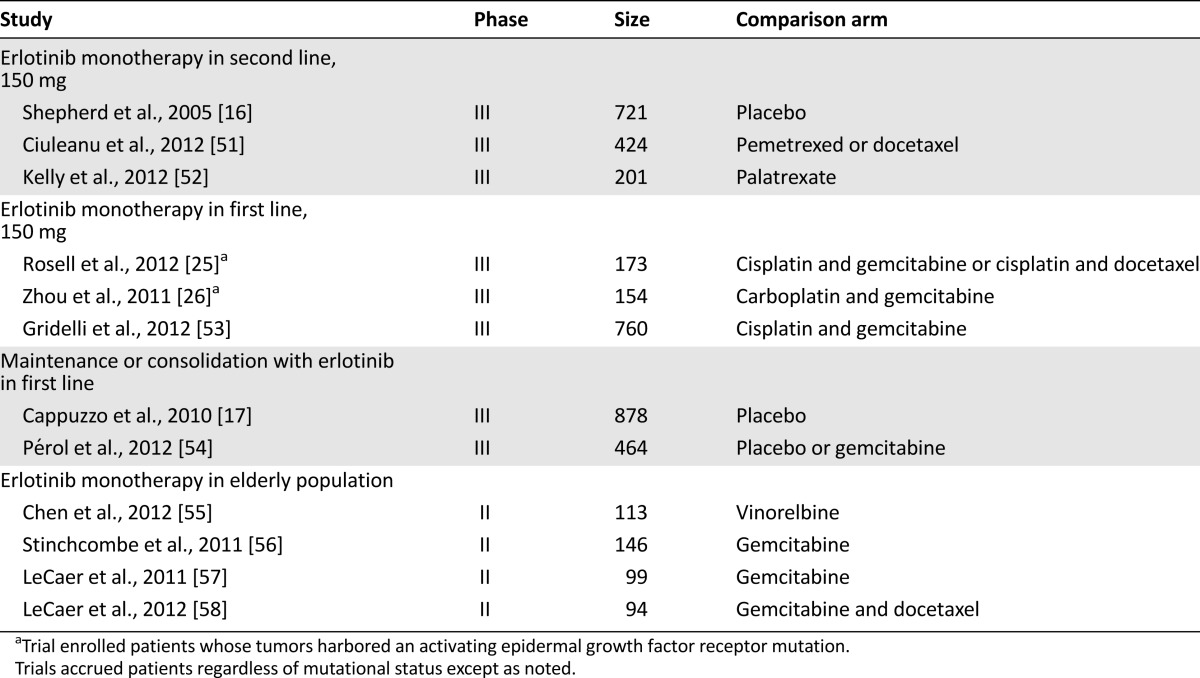

The 12 erlotinib reports included 7 phase III and 5 randomized phase II trials. Eleven of the 16 gefitinib studies were phase III, and 5 were randomized phase II trials. The erlotinib trials enrolled a total of 4,227 patients, whereas 7,043 patients were evaluated in the gefitinib studies, for a total of 11,270 patients. Although the comparisons with afatinib were limited, a total of 1,294 patients were enrolled in the three afatinib studies, of which 862 received afatinib. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the characteristics of each study. For the efficacy analyses comparing median OS and PFS distributions in the experimental arms of the erlotinib and gefitinib studies, we also analyzed trials according to the characteristics of the patients enrolled and the line of treatment, using the following groups, as shown in Tables 1 and 2: monotherapy in second line, monotherapy in first line (including the four trials in patient with mutated EGFR), maintenance or consolidation in first line, and monotherapy in the elderly population. We would argue that the very similar development portfolios make comparisons such as this one possible. For the meta-analyses, we refer in this report primarily to the results observed with the fixed-effect model.

Table 1.

Clinical trials evaluating the toxicity and efficacy of gefitinib

Table 2.

Clinical trials evaluating the toxicity and efficacy of erlotinib

Toxicity analysis

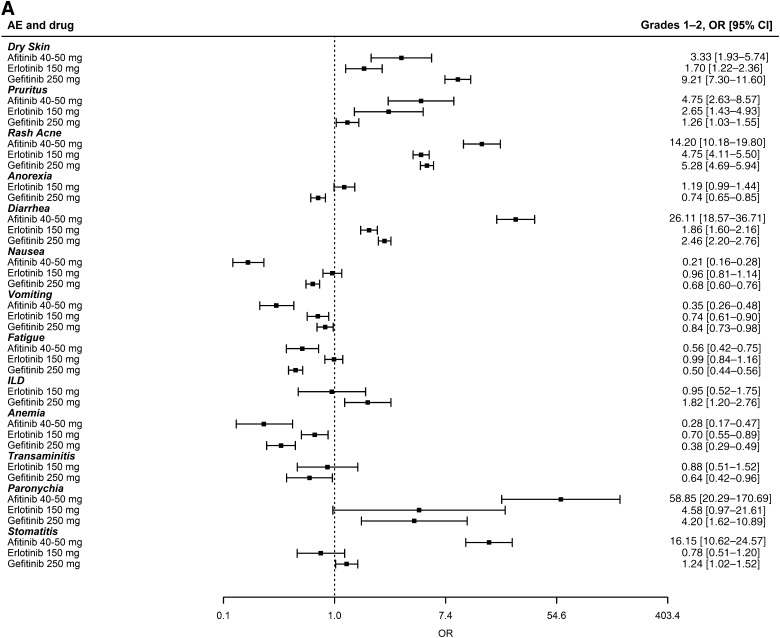

There is no direct comparison between erlotinib and gefitinib. For the AE meta-analyses to be generalizable to patients in this setting, the analyzed studies needed to have enrolled very similar patient populations with similar rates of AEs in the control arms. As noted in Tables 1 and 2, the trials were conducted in very similar populations. As shown in supplemental online Figure 3, the rates of AEs in the control arms of the erlotinib and gefitinib studies used in this meta-analysis were also very similar, with the only statistical difference being a marginally higher (p = .04) incidence of grade 3–4 dry skin observed among the controls of erlotinib studies. This similarity excludes any concern that erlotinib or gefitinib could appear better because the incidence of toxicities in its control arms were higher, making it look relatively less toxic. Figure 1A and 1B displays summaries of the 26 individual meta-analyses of grade 1–2 and 3–4 toxicities using the fixed-effect model (random-effects model presented in supplemental online Fig. 4A, 4B). Similar odds ratios can be seen for erlotinib and gefitinib. In grades 1–2, the odds ratio for diarrhea was statistically worse for gefitinib, whereas anorexia, pruritus, fatigue, anemia, and nausea had odds ratios that were statistically worse for erlotinib. In grades 3–4, the odds ratios for transaminitis and anemia were statistically worse for gefitinib, whereas the odds ratio for nausea was statistically worse for erlotinib. The odds of having ILD, a known toxicity observed with both erlotinib and gefitinib, compared with controls, was higher for gefitinib studies, although it did not achieve statistical significance; this may be explained in part by the additional gefitinib trials conducted in Asian populations in whom the incidence of ILD is higher [59]. In this context, we note that studies in Asian populations have not demonstrated significant differences between erlotinib and gefitinib with regard to the incidence of ILD [60]. Looking at afatinib toxicities, an increase in the odds of rash, diarrhea, paronychia, and stomatitis can be seen when compared with gefitinib and erlotinib (Fig. 1A, 1B). Finally, supplemental online Table 1 shows the incidence of common toxicities in gefitinib, erlotinib, and afatinib phase III clinical trials that enrolled patients with tumors harboring a mutant EGFR.

Figure 1.

Summary of 26 meta-analyses of grade 1–2 and 3–4 adverse events for 13 different toxicities (fixed-effect model). The OR and 95% CI for each toxicity is shown by drug subgroup (afatinib 40–50 mg, erlotinib 150 mg, and gefitinib 250 mg). ORs >1 indicate that the toxicity was more likely to occur in the study arm receiving the tyrosine kinase inhibitor. (A): Grade 1–2 adverse events. (B): Grade 3–4 adverse events.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; ILD, interstitial lung disease; OR, odds ratio.

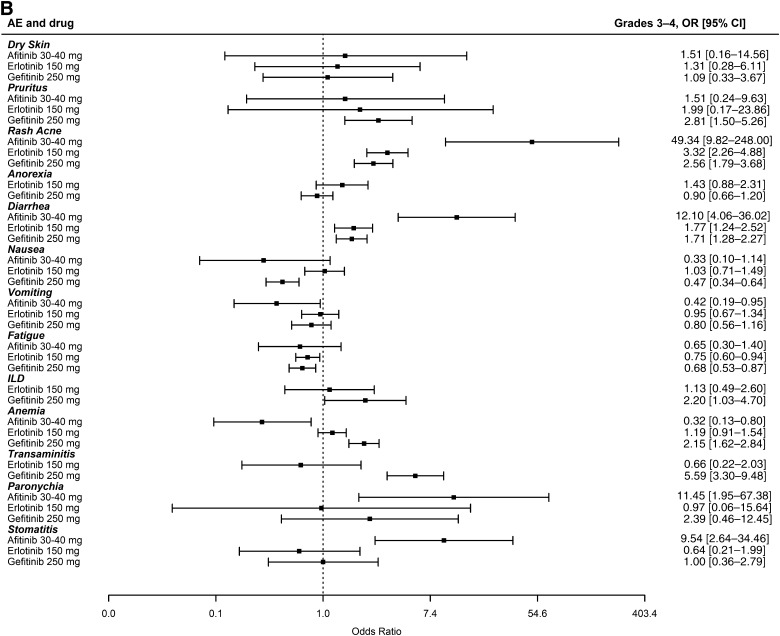

In contrast to the emphasis usually placed on grade 3–4 toxicities, we consider grade 1–2 toxicities to be equally if not more important because both erlotinib and gefitinib must be taken continuously. Furthermore, we argue that for drugs such as erlotinib and gefitinib, the ability to continue taking full doses captures the overall tolerability. This is best shown in Figure 2A and 2B depicting the meta-analyses for discontinuation and dose reduction using fixed- and random-effects models for gefitinib and erlotinib; insufficient information was available from the afatinib studies. Depending on the model, gefitinib appears similar to erlotinib or was discontinued and reduced compared with the respective control arm less often than erlotinib. Data for gefitinib at a dose of 500 mg orally each day are not shown but underscore how poorly tolerated this dose was and why its use was discontinued (supplemental online Fig. 5A, 5B). In addition, we note that the mean and median durations of treatment in the 27 trials that reported this information were 3.4 and 4.76 months for gefitinib and 3.45 and 4.6 months for erlotinib. Consequently, the differences in drug discontinuations and dose reductions cannot be ascribed to differences in the duration of therapy. Finally, the odds of “adverse event to death” compared with controls, meaning the likelihood of death as an adverse event compared with the controls, were greater for gefitinib than for erlotinib, although the numbers of events were small for both drugs (supplemental online Fig. 6).

Figure 2.

Forest plot depicting the meta-analysis using fixed- and random-effects models for drug discontinuation and dose reduction due to adverse events. An OR >1 indicates that the outcome was more likely to occur in the arm receiving the tyrosine kinase inhibitor. (A): OR for drug discontinuation. (B): OR for dose reduction.

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Efficacy Analysis

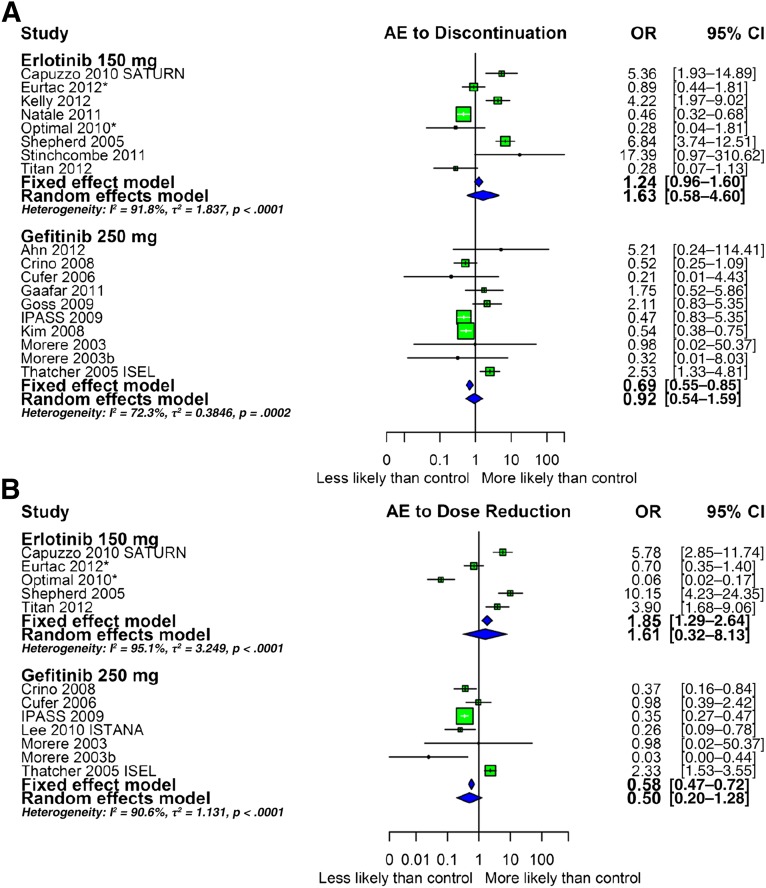

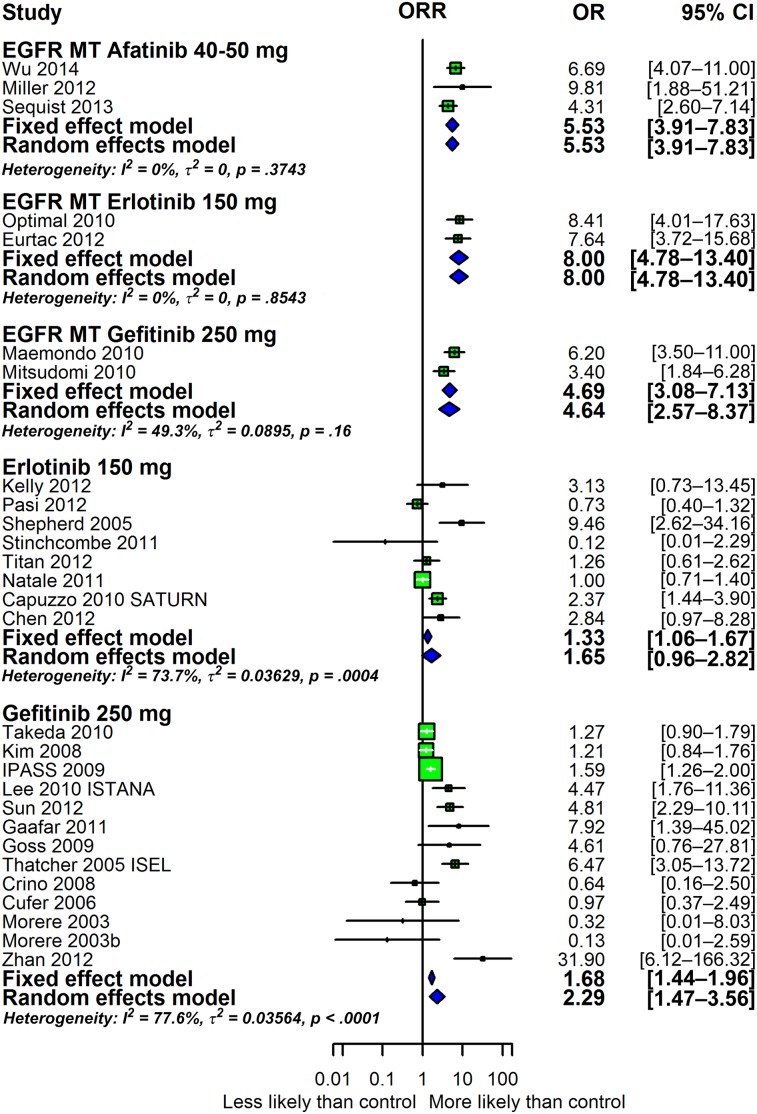

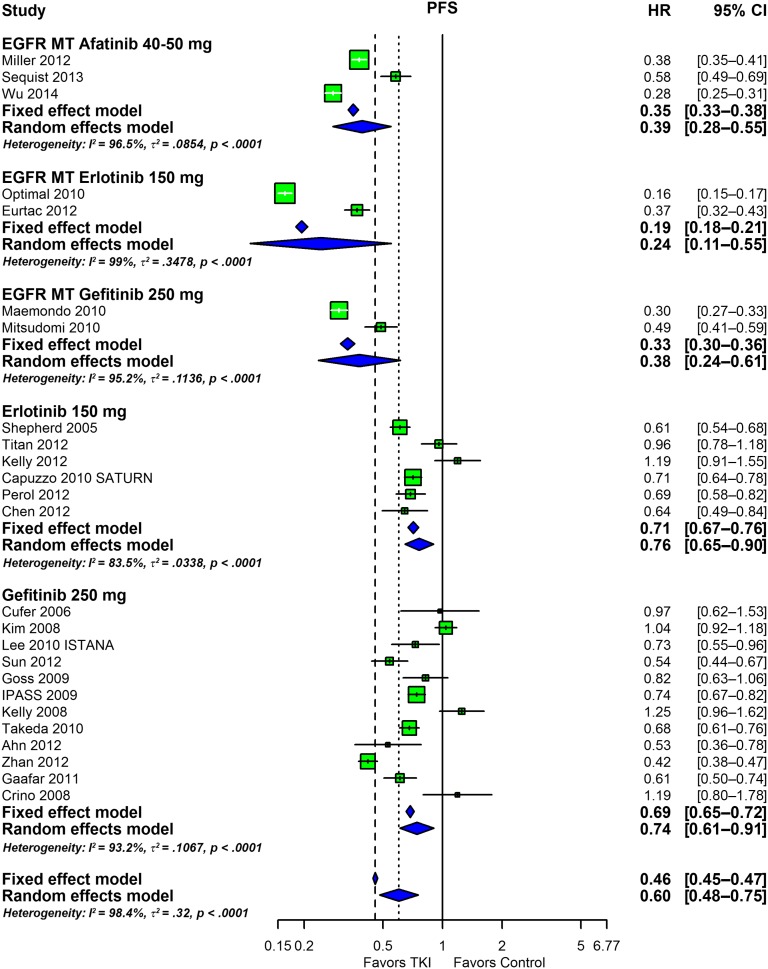

The efficacy data are summarized in Figures 3 and 4. In these analyses, the results of studies in patient populations that did not have the EGFR status of tumors determined were separated from the results of studies conducted in patients whose tumors had been shown to harbor an EGFR mutation. The overall response rates are presented as forest plots in Figure 3. In patients with tumors harboring a mutant EGFR, the response rates with afatinib, erlotinib, and gefitinib are similar, with overlapping confidence intervals. The two larger sets of erlotinib and gefitinib data depicted at the bottom consist of studies that enrolled patients in whom EGFR status had not been determined. In these studies, the efficacy of erlotinib (OR: 1.33; 95% CI: 1.06–1.67) and gefitinib (OR: 1.68; 95% CI: 1.44–1.96) was very similar. Not shown are data with 500 mg gefitinib administered orally each day that demonstrate a lack of efficacy, likely a consequence of the poor tolerability of this dose and the resultant discontinuation of drug (data not shown). Figure 4, in turn, shows the odds ratios estimated for PFS with the data arranged as in Figure 3. As for the overall response rate, a comparison of the afatinib studies to the erlotinib and gefitinib studies in first line in tumors harboring mutations in EGFR reveals very similar odds ratios with overlapping confidence intervals. The OS outcomes demonstrated for the three drugs have poorer hazard ratios than those for PFS (supplemental online Fig. 7), a common finding. Finally, supplemental online Figure 8 shows box plots of PFS and OS for all studies and for the subgroups listed in the Methods section.

Figure 3.

Forest plot depicting the efficacy of afatinib, erlotinib, and gefitinib in the studies evaluated as measured by ORR. An OR of >1 indicates that the arm with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) performed better. An OR of <1 indicates that the arm with the TKI performed worse. The three groups at the top designated EGFR MT are studies that enrolled only patients with tumors harboring mutations in EGFR. The two groups at the bottom represent erlotinib and gefitinib studies conducted in all patients without prior determination of EGFR status.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; OR, odds ratio; ORR, objective response rate.

Figure 4.

Forest plot depicting the meta-analysis of the PFS HR outcome. An odds ratio of <1 indicates that the arm with the tyrosine kinase inhibitor performed better than the control.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; HR, hazard ratio; PFS, progression-free survival; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Discussion

We conducted an extensive comparison of the toxicity and efficacy of erlotinib and gefitinib in patients with NSCLC. We concluded that gefitinib at an oral dose of 250 mg daily is as safe as erlotinib at an oral dose of 150 mg daily. Although small differences were observed that may appear to favor one drug over the other for the toxicities reported, these differences are not likely to be clinically important. The analyses also led us to conclude that the efficacy of gefitinib and erlotinib is comparable. A comparison with afatinib, for which much less information is currently available, suggests that afatinib is comparably effective, but more data are needed before definitive conclusions can be reached as to tolerability. The data demonstrate that gefitinib is active and safe as a cancer therapeutic for patients with NSCLC whose tumors harbor EGFR mutations and, if approved in the U.S., could offer physicians and their patients a valuable alternative to erlotinib.

Erlotinib and gefitinib are different molecules with different pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties. Pharmacokinetic variables such as bioavailability [61, 62] and metabolism [63] have been proposed to explain differences in subgroup analyses [64], and some have suggested that different binding capabilities related to erlotinib and gefitinib structure could explain partial differences in response with different EGFR mutations [65]. It has been argued that the latter could explain the apparent low activity of erlotinib in the wild-type EFGR population, although this point is controversial because the clinical evidence indicates that EGFR inhibitors are largely inactive against tumors harboring a wild-type EGFR and because a recent study concluded that docetaxel “chemotherapy is more effective than erlotinib for second-line treatment for previously treated patients with NSCLC who have wild-type EGFR tumors” [66]. As for other EGFR inhibitors, we note that although new drugs have emerged that bind irreversibly to the EGFR, their indications are still limited [67]. Afatinib, for example, is a HER1/HER2 inhibitor that was developed preclinically to be active against the T790M EGFR mutation, but it has shown limited activity in tumors harboring the T790M mutation [27, 68, 69]; however, afatinib was approved by the FDA in July 2013 for “first line treatment of patients with metastatic EGFR NSCLC with exon 19 deletions or exon 21 (L858R) substitution mutations as detected by an FDA-approved test” [70]. Although the approval was based on improvement in PFS, a recent study showed that, compared with a cisplatin regimen, afatinib improved the overall survival of patients whose tumors harbored an exon 19 deletion but not those with L858R substitutions, leading the authors to conclude that “EGFR del19-positive disease might be distinct from Leu858Arg- positive disease and these subgroups should be analysed separately in future trials” [71].

The FDA felt justified in rescinding gefitinib’s approval in 2005 because the confirmatory trials did not achieve the milestones envisioned at the time of accelerated approval in 2003. The importance of EGFR mutations with regard to the drug’s efficacy was not appreciated at that time, and rescinding the accelerated approval discouraged the subsequent pursuit of more specific indications in the U.S. Understandably, the financial and administrative burdens were felt to outweigh the potential financial gains from more restricted indications. Now that extensive safety and efficacy data with gefitinib have been accumulated, its approval for use in the U.S. should be reconsidered, especially for patients whose tumors harbor mutations in EGFR. It is important to note that safety was never a concern for the FDA, either at the time of the accelerated approval or when that approval was rescinded—times when the agency had extensive safety data. Furthermore, the 16 gefitinib studies we reviewed in this study did not uncover any safety concerns other than those already known and considered acceptable. We argue that safety could not be considered an issue, leaving only the issue of efficacy, and we clearly demonstrate that gefitinib is as efficacious as erlotinib.

Some may argue that the approval of erlotinib makes it unnecessary to approve gefitinib, given the similar activity profiles of the drugs; however, the approval of gefitinib in the U.S. would be valuable for several reasons. First, although the toxicity profiles of erlotinib and gefitinib are similar, they are not identical, and no evidence shows that difficulty tolerating one agent will lead to similar difficulty with the other. Approval of gefitinib would offer patients and their physicians a treatment option other than dose reduction if toxicity occurs during administration of erlotinib. Second, because the patent for gefitinib will expire years before that of erlotinib, a generic and much more affordable EGFR TKI option would be available sooner, and, as the data reported in this study demonstrate, its safety and efficacy will be guaranteed. With the increasing importance of health care costs, such generic alternatives are strongly desired, and it is unlikely that a generic manufacturer will invest in a registration strategy.

A limitation of this analysis is that no head-to-head comparisons have been conducted, and thus we were forced to compare the studies indirectly. Our study does not have the potential advantages of an individual patient data meta-analysis and is limited to aggregate study-level data or pooled analyses; however, for this particular question, it would be difficult if not impossible to obtain the raw data for the individual patients for all trials included. Limitations also include the heterogeneity within subgroups for certain outcomes (i.e., variation between studies exists beyond that for which treatment group accounts) and the availability of information (i.e., studies did not report information for all AEs examined and/or reported summary data rather than patient-level data). In addition, some might argue the 150-mg erlotinib dose is the maximum tolerated dose but that the 250-mg gefitinib dose is not, and this may “penalize” erlotinib; however, these are the approved doses and the doses for which data were available. We also recognize that the inclusion of patients with and without mutations makes analysis more difficult. Despite this, considering the questions addressed, the amount of data analyzed can be viewed as an advantage.

Conclusion

We demonstrated in this review what many have mentioned, known, or suspected: erlotinib and gefitinib are comparably effective. The data clearly demonstrate that in patients with NSCLC, gefitinib is safe, tolerable, and efficacious as monotherapy. Its activity profile in tumors harboring a mutant EGFR is comparable to those of erlotinib and afatinib, and we can envision its use in these tumors. We believe that the accumulated evidence with erlotinib and gefitinib indicates gefitinib’s activity and safety as a cancer therapeutic for patients with NSCLC is at least as good as that of erlotinib.

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

This article is available for continuing medical education credit at CME.TheOncologist.com.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Brigit O’Sullivan from the NIH library for providing expert research and bibliographic assistance for this article.

Footnotes

Editor's Note: See the related commentary by Lecia V. Sequist on page 335 of this issue.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Mauricio Burotto, Elisabet E. Manasanch, Tito Fojo

Collection and/or assembly of data: Mauricio Burotto, Elisabet E. Manasanch, Julia Wilkerson, Tito Fojo

Data analysis and interpretation: Mauricio Burotto, Julia Wilkerson, Tito Fojo

Manuscript writing: Mauricio Burotto, Julia Wilkerson, Tito Fojo

Final approval of manuscript: Mauricio Burotto, Elisabet E. Manasanch, Julia Wilkerson, Tito Fojo

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, et al. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen X, Zhu Q, Zhu L, et al. Clinical perspective of afatinib in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2013;81:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstraw P, Ball D, Jett JR, et al. Non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet. 2011;378:1727–1740. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62101-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas A, Rajan A, Lopez-Chavez A, et al. From targets to targeted therapies and molecular profiling in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:577–585. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mds478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li T, Kung HJ, Mack PC, et al. Genotyping and genomic profiling of non-small-cell lung cancer: Implications for current and future therapies. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1039–1049. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.3753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park K, Goto K. A review of the benefit-risk profile of gefitinib in Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:561–573. doi: 10.1185/030079906X89847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kwak EL, Bang YJ, Camidge DR, et al. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase inhibition in non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1693–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1006448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaw AT, Kim DW, Mehra R, et al. Ceritinib in ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1189–1197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaw AT, Kim DW, Nakagawa K, et al. Crizotinib versus chemotherapy in advanced ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:2385–2394. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen MH, Williams GA, Sridhara R, et al. United States Food and Drug Administration Drug Approval summary: Gefitinib (ZD1839; Iressa) tablets. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1212–1218. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thatcher N, Chang A, Parikh P, et al. Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer) Lancet. 2005;366:1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67625-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.FDA alert for healthcare professionals: Gefitinib (marketed as Iressa). Available at http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm126182.pdf. Accessed January 18, 2015.

- 14.Kim ES, Hirsh V, Mok T, et al. Gefitinib versus docetaxel in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer (INTEREST): A randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372:1809–1818. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61758-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.FDA approves new drug for the most common type of lung cancer drug shows survival benefit. Available at http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/2004/ucm108378.htm. Accessed January 18, 2015.

- 16.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cappuzzo F, Ciuleanu T, Stelmakh L, et al. Erlotinib as maintenance treatment in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:521–529. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70112-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.FDA approval for erlotinib hydrochloride. Available at http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/druginfo/fda-erlotinib-hydrochloride. Accessed January 18, 2015.

- 19.Paez JG, Jänne PA, Lee JC, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: Correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukuoka M, Yano S, Giaccone G, et al. Multi-institutional randomized phase II trial of gefitinib for previously treated patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (the IDEAL 1 trial) J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2237–2246. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giaccone G, Herbst RS, Manegold C, et al. Gefitinib in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A phase III trial—INTACT 1. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:777–784. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2380–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): An open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:121–128. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): A multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:239–246. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou C, Wu YL, Chen G, et al. Erlotinib versus chemotherapy as first-line treatment for patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (OPTIMAL, CTONG-0802): A multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:735–742. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70184-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N, et al. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3327–3334. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hirsch FR, Bunn PA., Jr A new generation of EGFR tyrosine-kinase inhibitors in NSCLC. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:442–443. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70124-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee CK, Brown C, Gralla RJ, et al. Impact of EGFR inhibitor in non-small cell lung cancer on progression-free and overall survival: A meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:595–605. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen X, Liu Y, Røe OD, et al. Gefitinib or erlotinib as maintenance therapy in patients with advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2013;8:e59314. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fan WC, Yu CJ, Tsai CM, et al. Different efficacies of erlotinib and gefitinib in taiwanese patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer: A retrospective multicenter study. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:148–155. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181f77b27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murphy M, Stordal B. Erlotinib or gefitinib for the treatment of relapsed platinum pretreated non-small cell lung cancer and ovarian cancer: A systematic review. Drug Resist Updat. 2011;14:177–190. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paz-Ares L, Soulières D, Melezínek I, et al. Clinical outcomes in non-small-cell lung cancer patients with EGFR mutations: Pooled analysis. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:51–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00991.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petrelli F, Borgonovo K, Cabiddu M, et al. Efficacy of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with EGFR-mutated non-small-cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis of 13 randomized trials. Clin Lung Cancer. 2012;13:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shao YY, Shau WY, Lin ZZ, et al. Comparison of gefitinib and erlotinib efficacies as third-line therapy for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller VA, Hirsh V, Cadranel J, et al. Afatinib versus placebo for patients with advanced, metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer after failure of erlotinib, gefitinib, or both, and one or two lines of chemotherapy (LUX-Lung 1): A phase 2b/3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:528–538. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu YL, Zhou C, Hu CP, et al. Afatinib versus cisplatin plus gemcitabine for first-line treatment of Asian patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring EGFR mutations (LUX-Lung 6): An open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:213–222. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70604-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwarzer G. Meta-analysis with R. R package version 2.5-1. 2013. Available at http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/meta/index.html. Accessed March 6, 2015.

- 39.Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J Stat Softw. 2010;36:1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun JM, Lee KH, Kim SW, et al. Gefitinib versus pemetrexed as second-line treatment in patients with nonsmall cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy (KCSG-LU08-01): An open-label, phase 3 trial. Cancer. 2012;118:6234–6242. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cufer T, Vrdoljak E, Gaafar R, et al. Phase II, open-label, randomized study (SIGN) of single-agent gefitinib (IRESSA) or docetaxel as second-line therapy in patients with advanced (stage IIIb or IV) non-small-cell lung cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 2006;17:401–409. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000203381.99490.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee DH, Park K, Kim JH, et al. Randomized phase III trial of gefitinib versus docetaxel in non-small cell lung cancer patients who have previously received platinum-based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1307–1314. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goss G, Ferry D, Wierzbicki R, et al. Randomized phase II study of gefitinib compared with placebo in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer and poor performance status. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2253–2260. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.4408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morère JF, Bréchot JM, Westeel V, et al. Randomized phase II trial of gefitinib or gemcitabine or docetaxel chemotherapy in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer and a performance status of 2 or 3 (IFCT-0301 study) Lung Cancer. 2010;70:301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kelly K, Chansky K, Gaspar LE, et al. Phase III trial of maintenance gefitinib or placebo after concurrent chemoradiotherapy and docetaxel consolidation in inoperable stage III non-small-cell lung cancer: SWOG S0023. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2450–2456. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.4824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gaafar RM, Surmont VF, Scagliotti GV, et al. A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III intergroup study of gefitinib in patients with advanced NSCLC, non-progressing after first line platinum-based chemotherapy (EORTC 08021/ILCP 01/03) Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:2331–2340. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang L, Ma S, Song X, et al. Gefitinib versus placebo as maintenance therapy in patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (INFORM; C-TONG 0804): A multicentre, double-blind randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:466–475. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Takeda K, Hida T, Sato T, et al. Randomized phase III trial of platinum-doublet chemotherapy followed by gefitinib compared with continued platinum-doublet chemotherapy in Japanese patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Results of a west Japan thoracic oncology group trial (WJTOG0203) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:753–760. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.3445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahn MJ, Yang JC, Liang J, et al. Randomized phase II trial of first-line treatment with pemetrexed-cisplatin, followed sequentially by gefitinib or pemetrexed, in East Asian, never-smoker patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2012;77:346–352. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crinò L, Cappuzzo F, Zatloukal P, et al. Gefitinib versus vinorelbine in chemotherapy-naive elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (INVITE): A randomized, phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4253–4260. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ciuleanu T, Stelmakh L, Cicenas S, et al. Efficacy and safety of erlotinib versus chemotherapy in second-line treatment of patients with advanced, non-small-cell lung cancer with poor prognosis (TITAN): A randomised multicentre, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:300–308. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70385-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kelly K, Azzoli CG, Zatloukal P, et al. Randomized phase 2b study of pralatrexate versus erlotinib in patients with stage IIIB/IV non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) after failure of prior platinum-based therapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:1041–1048. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31824cc66c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gridelli C, Ciardiello F, Gallo C, et al. First-line erlotinib followed by second-line cisplatin-gemcitabine chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: The TORCH randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3002–3011. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pérol M, Chouaid C, Pérol D, et al. Randomized, phase III study of gemcitabine or erlotinib maintenance therapy versus observation, with predefined second-line treatment, after cisplatin-gemcitabine induction chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3516–3524. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.9782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen YM, Tsai CM, Fan WC, et al. Phase II randomized trial of erlotinib or vinorelbine in chemonaive, advanced, non-small cell lung cancer patients aged 70 years or older. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:412–418. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31823a39e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stinchcombe TE, Peterman AH, Lee CB, et al. A randomized phase II trial of first-line treatment with gemcitabine, erlotinib, or gemcitabine and erlotinib in elderly patients (age ≥70 years) with stage IIIB/IV non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:1569–1577. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182210430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.LeCaer H, Barlesi F, Corre R, et al. A multicentre phase II randomised trial of weekly docetaxel/gemcitabine followed by erlotinib on progression, vs the reverse sequence, in elderly patients with advanced non small-cell lung cancer selected with a comprehensive geriatric assessment (the GFPC 0504 study) Br J Cancer. 2011;105:1123–1130. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.LeCaer H, Greillier L, Corre R, et al. A multicenter phase II randomized trial of gemcitabine followed by erlotinib at progression, versus the reverse sequence, in vulnerable elderly patients with advanced non small-cell lung cancer selected with a comprehensive geriatric assessment (the GFPC 0505 study) Lung Cancer. 2012;77:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cataldo VD, Gibbons DL, Pérez-Soler R, et al. Treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer with erlotinib or gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:947–955. doi: 10.1056/NEJMct0807960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hotta K, Kiura K, Takigawa N, et al. Comparison of the incidence and pattern of interstitial lung disease during erlotinib and gefitinib treatment in Japanese Patients with non-small cell lung cancer: The Okayama Lung Cancer Study Group experience. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:179–184. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181ca12e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ling J, Fettner S, Lum BL, et al. Effect of food on the pharmacokinetics of erlotinib, an orally active epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine-kinase inhibitor, in healthy individuals. Anticancer Drugs. 2008;19:209–216. doi: 10.1097/CAD.0b013e3282f2d8e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cantarini MV, McFarquhar T, Smith RP, et al. Relative bioavailability and safety profile of gefitinib administered as a tablet or as a dispersion preparation via drink or nasogastric tube: Results of a randomized, open-label, three-period crossover study in healthy volunteers. Clin Ther. 2004;26:1630–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li J, Zhao M, He P, et al. Differential metabolism of gefitinib and erlotinib by human cytochrome P450 enzymes. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3731–3737. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bronte G, Rolfo C, Giovannetti E, et al. Are erlotinib and gefitinib interchangeable, opposite or complementary for non-small cell lung cancer treatment? Biological, pharmacological and clinical aspects. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;89:300–313. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yun CH, Boggon TJ, Li Y, et al. Structures of lung cancer-derived EGFR mutants and inhibitor complexes: Mechanism of activation and insights into differential inhibitor sensitivity. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Garassino MC, Martelli O, Broggini M, et al. Erlotinib versus docetaxel as second-line treatment of patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer and wild-type EGFR tumours (TAILOR): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:981–988. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70310-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gridelli C, Felip E. Targeted therapies development in the treatment of advanced nonsmall cell lung cancer. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:415641. doi: 10.1155/2011/415641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Langer CJ. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition in mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: Is afatinib better or simply newer? J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3303–3306. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.8782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Afatinib. Available at http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/ucm360574.htm. Accessed January 18, 2015.

- 70.Katakami N, Atagi S, Goto K, et al. LUX-Lung 4: A phase II trial of afatinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer who progressed during prior treatment with erlotinib, gefitinib, or both. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3335–3341. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.0981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang JC, Wu YL, Schuler M, et al. Afatinib versus cisplatin-based chemotherapy for EGFR mutation-positive lung adenocarcinoma (LUX-Lung 3 and LUX-Lung 6): Analysis of overall survival data from two randomised, phase 3 trials. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:141–151. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71173-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.