Abstract

Synovial sarcoma is the fourth most common type of soft-tissue sarcoma (following undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, liposarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma), and should be considered a high-grade neoplasm with a high number of local recurrences and late metastases. Synovial sarcoma predominantly occurs in adolescents and young adults, and typically arises near the joints of the lower extremity. However, this tumor can also occur at uncommon sites such as the abdominal wall, which is illustrated in this article. Furthermore, we reviewed the available literatures on the clinical, pathological and radiological appearances, as well as the current knowledge concerning treatment options and prognosis.

Keywords: Synovial sarcoma, abdominal wall, imaging, oncology, surgery

CASE REPORT

A 44-year-old woman with a blank medical history was referred to our outpatient clinic with a slowly growing palpable mass on the left side of the anterior abdominal wall, first noticed by the patient one year before. Computed tomography (CT) revealed a round, heterogeneously enhancing soft tissue mass with a small punctate peripheral calcification and a size of 6 × 5 × 6 centimetres (Figure 1). At magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, the soft tissue mass had an inhomogeneous low to intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images and an increased signal intensity on T2-weighted images with a central hypointensity, compared to muscle signal intensity (Figures 2A–D). After intravenous administration of Gadolinium, a heterogeneous enhancement pattern was observed (Figure 2E–H). Based on the patient/clinical characteristics and imaging findings, deep-seated fibromatosis and synovial sarcoma were the two most likely diagnoses. An ultrasound guided core biopsy (Figure 3) was performed which showed a synovial sarcoma with a t(X;18)(p11;q11) translocation, involving SYT-SSX1. Routine abdominal and chest CT revealed no metastases. She underwent a radical resection of the synovial sarcoma in the anterior abdominal wall including resection of the left rectus abdominis muscle, with reconstruction of the anterior abdominal wall using a mesh. Histopathologic examination of the resection specimen revealed a 7 centimetre biphasic synovial sarcoma with extensive necrosis (Figures 4A and 4B). The resection margins were negative. The postoperative period was uneventful and she was discharged after three days. One year postoperative, the condition is stable with no evidence of local tumor recurrence.

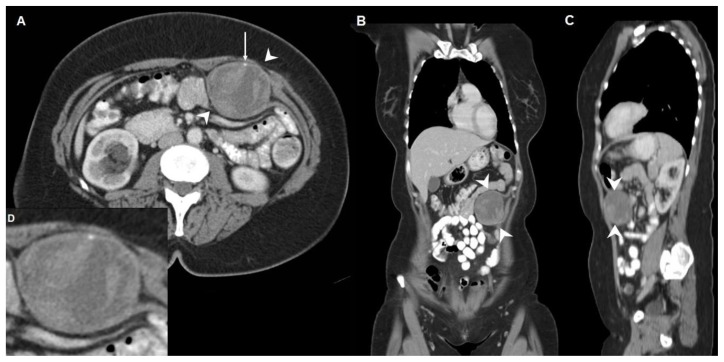

Figure 1.

Axial (A), coronal (B), sagittal (C) and axial magnified (D) contrast-enhanced CT image (168 mAs, 120 kV, 5 mm slice thickness, 106 ml Xenetix 300) of a synovial sarcoma in a 44-year-old woman located between the left rectus abdominis muscle and the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis muscle, outside the peritoneal cavity (arrowheads).

A round, heterogeneous enhancing, sharply marginated, soft tissue mass with a size of 6 × 5 × 6 centimetres is present. A small punctate calcification is visible in the periphery of the lesion (long arrow in Figure 1A). No metastases were present in the abdominal and thoracic cavity.

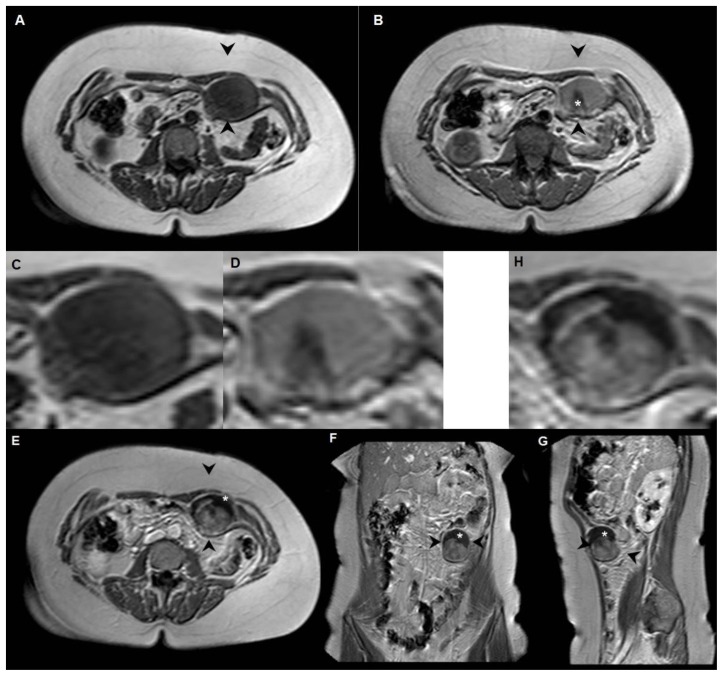

Figure 2.

Synovial sarcoma in a 44-year-old woman located between the left rectus abdominis muscle and the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis muscle, outside the peritoneal cavity.

A: axial T1-weighted MR image (1.5T, TE 30, TR 500) shows a round soft-tissue mass with low to intermediate signal intensity, with diameters of 6 × 4 × 6 centimetres (arrowheads).

B: on the axial T2-weighted MR image (1.5T, TE 90, TR 1500) the signal intensity is predominantly intermediate, with central hypointensity (*).

C and D: axial magnification of the lesion at T1-weighted (C) and T2-weighted (D) MR imaging.

E (axial), F (coronal), G (sagittal) and H (axial magnification) T1-weighted MR image after intravenous administration of Gadolinium (1.5T, TE 14, TR 560, 15 ml Dotarem): the soft-tissue mass shows heterogeneous enhancement with a fibrotic component in the cranial part of the lesion (*).

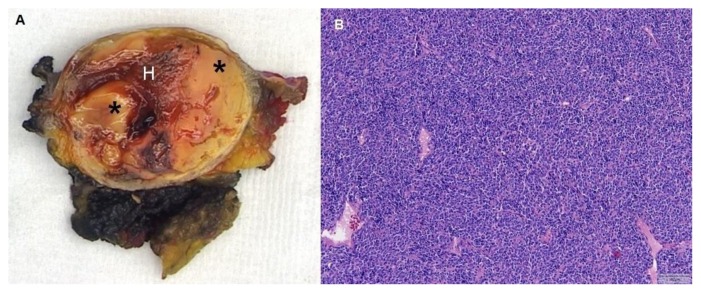

Figure 3.

Ultrasound guided core biopsy (8 MHz, linear transducer) of a synovial sarcoma in a 44-year-old woman located between the left rectus abdominis muscle and the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis muscle, outside the peritoneal cavity.

A round, hypoechoic solid mass is visible (arrowheads) with several internal echoes. Color Doppler ultrasound revealed no internal vascularity.

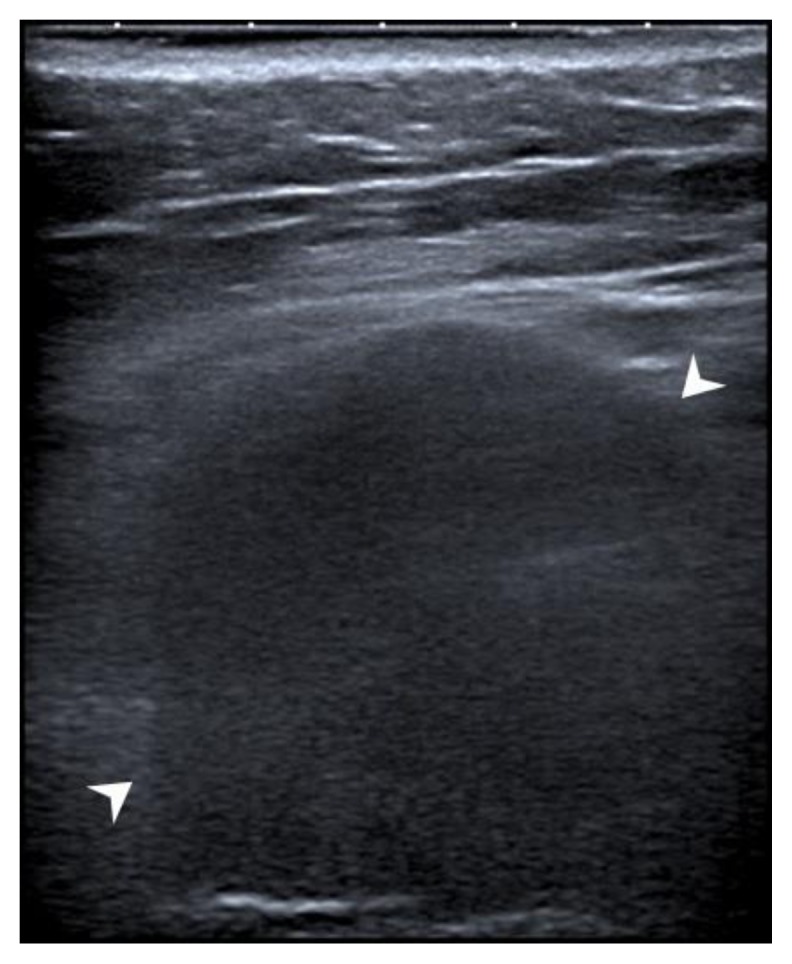

Figure 4.

Synovial sarcoma in a 44-year-old woman located between the left rectus abdominis muscle and the aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis muscle, outside the peritoneal cavity.

A: Photograph of the sectioned gross specimen shows the synovial sarcoma with solid components (*) and hemorrhage (H).

B: Microscopically, a monotonous spindle cell lesion was seen with round to oval nuclei (hematoxylin and eosin stain, magnification 100x).

DISCUSSION

Etiology and demographics

Synovial sarcomas account for approximately 8% of all primary soft-tissue malignancies worldwide. It is seen most frequently in adolescents and young adults [1,2]. The majority of tumors present at 15–40 years of age [1,2]. Men and women are affected equally, with no race or ethnic predilection [1,3]. Patients usually present with a palpable, slowly growing, sometimes painful soft-tissue mass. This gradual onset often causes a delay in diagnosis.

Synovial sarcomas most often occur outside the joints, and histologically they do not resemble synovial structures. However, owing to the similarity between synovial sarcoma tumor cells and primitive synoviocytes, the term synovial sarcoma was introduced. In fact, synovial sarcomas derive from multipotent stem cells that are capable of differentiating into mesenchymal and/or epithelial structures [4].

Histologically, three main subtypes have been described: biphasic, monophasic and poorly differentiated. Biphasic synovial sarcomas (20%–30% of cases) have an epithelial and a spindle cell component in varying proportions, and classically the epithelial cells form glands [4]. Monophasic synovial sarcomas (most common subtype: 50%–60%) are entirely composed of spindle cells [4]. In 15%–25% of synovial sarcomas, a poorly differentiated subtype is described, often with small blue round cell morphology and high mitotic activity [3]. Other characteristic pathologic features include intratumoral calcification or ossification, cystic changes, and necrosis [5]. Although synovial sarcomas can be graded according to mitotic index, necrosis, and tumor differentiation, it always should be considered a high-grade sarcoma [6]. In more than 90% of cases, synovial sarcomas contain the characteristic translocation t(X;18)(p11.2;q11.2), which involves the SYT gene on chromosome 18 and the SSX gene on the X chromosome (SSX1, SSX2, or SSX4). This can be identified using FISH or RT-PCR techniques [7]. SYT-SSX1 fusion is present in almost two-thirds of cases, SYT-SSX2 fusion in one-third of patients, whereas SYT-SSX4 fusion is only present in very rare cases [8].

Clinical and imaging findings

The most common primary site of synovial sarcoma is the extremities, with the lower extremity being most often affected, accounting for almost 70% of cases [5,6]. The single most frequent site of involvement is the popliteal fossa of the knee [3]. Rare locations include the head and neck (5%), trunk (8%), abdomen and retroperitoneum (7%) [6,7]. The incidence of synovial sarcomas located within the anterior abdominal wall is unknown, but it is a rare site [9].

Conventional radiographs in synovial sarcoma patients can be normal, however, almost half of the cases show a nonspecific soft-tissue mass, and 20% show soft-tissue calcifications and/or bony erosion [10].

At ultrasound, synovial sarcoma can appear as a solid hypoechoic soft-tissue mass or appears heterogeneous with more echoic areas and irregular margins, but this imaging modality is non-specific in distinguishing malignant features [11]. In addition, ultrasound is often used to guide histologic core biopsies.

CT typically shows a heterogeneous, noninfiltrative, well-circumscribed mass with attenuation values similar to or slightly lower than that of muscle. Punctate calcifications are seen at the periphery of the mass in up to 30% of synovial sarcomas. In addition, low-attenuation areas may be present, simulating cystic changes or (old) hematoma. After intravenous contrast administration, most cases show heterogeneous enhancement [11–13].

MR imaging is the modality of choice for diagnosis of synovial sarcoma. The typical appearance of synovial sarcoma on T1-weighted spin-echo MR images is a heterogeneous multilobulated soft-tissue mass with signal intensity equal to or slightly higher than that of muscle (Figure 2A). On T2-weighted spin-echo MR images, synovial sarcomas predominantly show prominent heterogeneity and high signal intensity (Figure 2B). Often, on T2-weighted images a triple signal pattern is present, consisting of intermixed areas of low, intermediate and high signal intensity (triple sign) [3,5,14,15]. Frequently, areas of haemorrhage, cystic changes, and fluid levels are present. MR imaging is also an excellent technique for assessment of local invasion (i.e. bone involvement, neurovascular encasement, and/or muscular invasion), thereby judging aggressiveness of the tumor and attributing to preoperative surgical planning. After intravenous injection of Gadolinium, a heterogeneous enhancement pattern is most often seen in synovial sarcomas [3].

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) uptake values in synovial sarcoma patients may be useful as a means to identify patients at high risk for poor outcome. A pretherapy standard uptake value greater than 4.35 has been associated with high risk for developing local recurrences and metastatic disease [16].

Differential diagnoses

When localized within the anterior abdominal wall in an adult female patient up to forty-five years of age, the presence of tiny calcifications at CT and intratumoral cystic changes at CT or MR imaging might differentiate synovial sarcoma from abdominal deep-seated fibromatosis [17]. This is another rare, locally aggressive soft-tissue tumor, however, without tendency to metastasize. Other entities to be considered in the differential diagnosis are hematoma (variable MR appearance according to the degradation of red blood cells, no significant contrast enhancement), injection granuloma (hypointense on T1 and variable appearance on T2 with adjacent soft-tissue changes and air), abdominal wall endometriosis (T1/T2 iso-/hyperintense, frequently enhancing after intravenous contrast administration), lymphoma (nonspecific imaging features), and abdominal wall abscess (collection with rim enhancement and high T2 signal intensity) [18]. Table 2 summarizes imaging characteristics of the differential diagnosis for synovial sarcoma of the anterior abdominal wall.

Table 2.

Differential diagnosis table for synovial sarcoma of the anterior abdominal wall.

| Entity | US | MRI | CT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Synovial sarcoma [3,5,11–15] |

|

|

|

| Abdominal deep-seated fibromatosis (desmoid tumor) [17] |

|

|

|

| Hematoma [18] |

|

|

|

| Injection granuloma [18] | Hyperechoic nodules with poorly defined margins |

|

|

| Abdominal wall endometriosis [18] | Nonspecific |

|

|

| Lymphoma [18] | Nonspecific | Nonspecific | Nonspecific |

| Abscess [18] |

|

|

|

Treatment and prognosis

Similar to the treatment of other soft-tissue sarcomas, local control of synovial sarcomas is primarily achieved by adequate surgical excision, consisting of en bloc resection of the tumor, its pseudocapsule, and a normal cuff of surrounding tissue of at least 1 centimetre [7]. Not removing an adequate rim of normal surrounding tissue has been associated with an increase in the risk of local recurrence by eightfold [19]. The role of adjuvant radiation therapy and chemotherapy remains controversial, as their influence on local control and overall survival is still unclear [19]. Adjuvant radiation therapy and chemotherapy is mostly offered to patients with marginally resected tumors or residual disease, thereby improving local control rate [7]. Chemotherapy as a primary treatment modality is mainly reserved for patients with metastatic disease, and improved disease-specific survival rates have been reported with ifosfamide-based regimens [6,20].

Reported 5- and 10-year survival rates range from 56% to 76%, and from 45% to 63%, respectively [19,21,22]. Synovial sarcoma is associated with local recurrence and distant metastases. Metastases occur in 50%–70% of cases, which are mainly located in the lungs, followed by regional lymph nodes [21]. Because local recurrences and metastatic disease in synovial sarcoma patients occur rather late, even after 5–10 years, these patients should be followed for more than 10 years [21]. Many prognostic factors, such as patient age, tumor size, surgical margins, histological subtype, tumor grade, and fusion type, have been reported, however, only tumor size greater than 5 centimetres has consistently been associated with a negative outcome [21].

Conclusion

Synovial sarcoma is the fourth most common type of soft-tissue sarcoma (following undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma, liposarcoma, and rhabdomyosarcoma), and should be considered a high-grade neoplasm. Synovial sarcoma predominantly occurs in adolescents and young adults, presenting as a slowly growing, large juxtaarticular mass in the lower extremity. Uncommon sites include the head and neck, trunk, abdomen and retroperitoneum. Histopathologically, most synovial sarcomas contain a characteristic translocation between chromosomes X and 18. MR imaging remains the optimal modality for diagnosis and staging. Best local control is achieved by radical surgical excision. Because of its tendency for late local recurrence and metastases, a follow-up period of at least 10 years seems reasonable.

TEACHING POINT

The anterior abdominal wall is an uncommon site of synovial sarcoma, which is the fourth most common type of soft-tissue sarcoma. MR imaging remains the optimal modality for diagnosis and staging, best local control is achieved by radical surgical excision, and because of its tendency for late local recurrence and metastases, a follow-up period of at least 10 years seems reasonable.

Table 1.

Summary table for synovial sarcoma of the anterior abdominal wall.

| Etiology: | In more than 90% of cases, synovial sarcomas contain the characteristic translocation t(X;18)(p11.2;q11.2) [7]. |

| Incidence: | Approximately 8% of all primary soft-tissue malignancies worldwide [1,2]. |

| Gender ratio: | Men and women are affected equally, with no race or ethnic predilection [1,3]. |

| Age predilection: | The majority of tumors present at 15–40 years of age [1,2]. |

| Risk factors: | No specific risk factors for synovial sarcoma have been reported. |

| Treatment: | Adequate surgical excision is the primary treatment [7]. The role of adjuvant radiation therapy and chemotherapy remains controversial [19]. |

| Prognosis: | Five- and 10-year survival rates range from 56% to 76%, and from 45% to 63%, respectively [19,21,22]. Metastases occur in 50%–70% of patients, mainly pulmonary and lymphatic [21]. |

| Findings on imaging: |

|

ABBREVIATIONS

- CT

Computed Tomography

- FDG-PET

18f-Fluorodeoxyglucose Positron Emission Tomography

- FISH

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization

- MR

Magnetic Resonance

- RT-PCR

Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction

REFERENCES

- 1.Kransdorf MJ. Malignant soft-tissue tumors in a large referral population: distribution of diagnoses by age, sex, and location. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164(1):129–134. doi: 10.2214/ajr.164.1.7998525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Trassard M, Le Doussal V, Hacène K, et al. Prognostic factors in localized primary synovial sarcoma: a multicenter study of 128 adult patients. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(2):525–534. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.2.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphey MD, Gibson MS, Jennings BT, Crespo-Rodríguez AM, Fanburg-Smith J, Gajewski DA. From the archives of the AFIP: imaging of synovial sarcoma with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2006;26(5):1543–1565. doi: 10.1148/rg.265065084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fisher C. Synovial sarcoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 1998;2(6):401–421. doi: 10.1016/s1092-9134(98)80042-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakri A, Shinagare AB, Krajewski KM, et al. Synovial sarcoma: imaging features of common and uncommon primary sites, metastatic patterns, and treatment response. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(2):W208–215. doi: 10.2214/AJR.11.8039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrari A, Gronchi A, Casanova M, et al. Synovial sarcoma: a retrospective analysis of 271 patients of all ages treated at a single institution. Cancer. 2004;101(3):627–634. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eilber FC, Dry SM. Diagnosis and management of synovial sarcoma. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97(4):314–320. doi: 10.1002/jso.20974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dos Santos NR, de Bruijn DR, Geurts van Kessel A. Molecular mechanisms underlying human synovial sarcoma development. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2001;30(1):1–14. doi: 10.1002/1098-2264(2000)9999:9999<::aid-gcc1056>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fetsch JF, Meis JM. Synovial sarcoma of the abdominal wall. Cancer. 1993;72(2):469–477. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930715)72:2<469::aid-cncr2820720224>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horowitz AL, Resnick D, Watson RC. The roentgen features of synovial sarcomas. Clin Radiol. 1973;24(4):481–484. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(73)80158-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marzano L, Failoni S, Gallazzi M, Garbagna P. The role of diagnostic imaging in synovial sarcoma. Our experience. Radiol Med. 2004;107(5–6):533–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nakanishi H, Araki N, Sawai Y, et al. Cystic synovial sarcomas: imaging features with clinical and histopathologic correlation. Skeletal Radiol. 2003;32(12):701–707. doi: 10.1007/s00256-003-0690-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tateishi U, Hasegawa T, Beppu Y, Satake M, Moriyama N. Synovial sarcoma of the soft tissues: prognostic significance of imaging features. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2004;28(1):140–148. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200401000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirsch RJ, Yousem DM, Loevner LA, et al. Synovial sarcomas of the head and neck: MR findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;169(4):1185–1188. doi: 10.2214/ajr.169.4.9308488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones BC, Sundaram M, Kransdorf MJ. Synovial sarcoma: MR imaging findings in 34 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;161(4):827–830. doi: 10.2214/ajr.161.4.8396848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lisle JW, Eary JF, O’Sullivan J, Conrad EU. Risk assessment based on FDG-PET imaging in patients with synovial sarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(6):1605–1611. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0647-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teo HE, Peh WC, Shek TW. Case 84: desmoid tumor of the abdominal wall. Radiology. 2005;236(1):81–84. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2361031038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein L, Elsayes KM, Wagner-Bartak N. Subcutaneous abdominal wall masses: radiological reasoning. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198(2):W146–151. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.7238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Silva MV, McMahon AD, Reid R. Prognostic factors associated with local recurrence, metastases, and tumor-related death in patients with synovial sarcoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2004;27(2):113–121. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000047129.97604.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eilber FC, Brennan MF, Eilber FR, et al. Chemotherapy is associated with improved survival in adult patients with primary extremity synovial sarcoma. Ann Surg. 2007;246(1):105–113. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000262787.88639.2b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krieg AH, Hefti F, Speth BM, et al. Synovial sarcomas usually metastasize after >5 years: a multicenter retrospective analysis with minimum follow-up of 10 years for survivors. Ann Oncol. 2011;22(2):458–467. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mullen JR, Zagars GK. Synovial sarcoma outcome following conservation surgery and radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 1994;33(1):23–30. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(94)90082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]