Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study is to determine the epidemiological effectiveness of a first-line antiretroviral regimen with HIV protease inhibitor for preventing recurrent malaria in children under the range of HIV prevalence levels and malaria transmission intensities encountered in sub-Saharan Africa.

Design

A dynamic model of malaria transmission was developed using clinical data on the protease inhibitor extended posttreatment prophylactic effect of the antimalarial treatment, artemether-lumefantrine, in addition to parameter estimates from the literature.

Methods

To evaluate the benefits of HIV protease inhibitors on the health burden of recurrent malaria among children, we constructed a dynamic model of malaria transmission to both HIV-positive and HIV-negative children, parameterized by data from a recent clinical trial. The model was then evaluated under varying malaria transmission and HIV prevalence settings to determine the health benefits of HIV protease inhibitors in the context of artemether-lumefantrine treatment of malaria in children.

Results

Comparing scenarios of low, intermediate and high newborn HIV prevalence, in a range of malaria transmission settings, our dynamic model predicts that artemether-lumefantrine with HIV protease inhibitor based regimens prevents 0.03–0.10, 5.2–13.0 and 25.5–65.8 annual incidences of malaria per 1000 children, respectively. In addition, HIV protease inhibitors save 0.002–0.006, 0.22–0.8, 1.04–4.3 disability-adjusted life-years per 1000 children annually. Considering only HIV-infected children, HIV protease inhibitors avert between 278 and 1043 annual incidences of malaria per 1000 children.

Conclusion

The use of HIV protease inhibitor based regimens as first-line antiretroviral therapy for HIV is an effective measure for reducing recurrent malaria among HIV-infected children in areas where HIV and malaria are coendemic, and artemether-lumefantrine is a first-line antimalarial.

Keywords: antimalarial effects of protease inhibitors, antiretrovirals, HIV, HIV malaria coinfection, HIV protease, inhibitors, lumefantrine, malaria, mathematical model, pharmacology

Background

Sub-Saharan Africa suffers from devastating burdens of both HIV and malaria. HIV-positive children in malaria endemic areas have an elevated risk of clinical malaria and potentially more severe clinical outcomes compared with HIV-negative children due to compromised immune systems [1]. The use of HAART and other prophylactic measures in Africa has steadily improved with expanded access to potent combination drug regimens [2]. WHO-recommended first-line antiretroviral regimens for children currently include a dual-nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) with either an HIV nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), for children over 3 years of age, or an HIV protease inhibitor, for children under 3 years of age [3,4]. The choice of NNRTIs or protease inhibitor based HAART first-line antiretroviral drug regimens is a topic of current deliberation, as each drug has its own pros and cons [4–6]. For instance, although generic formulations of NNRTIs are more often available and relatively inexpensive, viral mutation can readily induce resistance to nearly all currently available drugs in the NNRTI class [6,7]. In contrast, although protease inhibitors are more expensive, they are becoming increasingly available and have higher genetic barriers to resistance [7,8]. Here, we explore another factor for consideration in the decision of which antiretroviral regimen should be implemented. Specifically, the interaction between protease inhibitors and antimalarial treatments has potential direct antimalarial effects and indirect benefits in terms of extending the posttreatment prophylactic effect of antimalarials [5,9,10].

Similarly to HIV, expanding availability of and advances in antimalarial treatments, namely the use of artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT), has reduced the global morbidity and mortality attributed to Plasmodium falciparum. The most widely adopted ACT, artemether-lumefantrine, combines a short-acting artemisinin with a longer acting, but less potent partner drug, lumefantrine. Building on the in-vitro antimalarial activity observed with protease inhibitors, a recent clinical trial in a high malaria endemic region of Uganda has shown that HIV-infected children treated with protease inhibitor based HAART have a 41% lower incidence of malaria than children on NNRTI-based HAART. Notably, the major impact of the HIV protease inhibitors appears to be an extension of the posttreatment prophylactic effect of artemether-lumefantrine for the prevention of recurrent malaria as compared with those children on NNRTI-based HAART [5,9]. This extension likely occurs due to protease inhibitor mediated inhibition of lumefantrine metabolism, and subsequent enhanced exposure over time [10]. The epidemiological impact of extended posttreatment prophylactic effect of artemether-lumefan-trine attributable to protease inhibitors has yet to be evaluated at the population level.

Using clinical and epidemiological data from a clinical trial regarding the effect of protease inhibitors as compared with NNRTIs on the incidence of malaria in HIV-infected children in highly endemic regions [5], we evaluated the population-level effectiveness of a first-line antiretroviral regimen with protease inhibitors for reducing the health burden of recurrent malaria among children in sub-Saharan Africa in areas with varying levels of HIV and malaria prevalence. For this analysis, we developed a dynamic model of malaria transmission that takes into account both HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected children. Given the uncertainty of predictions in low malaria transmission settings [entomological inoculation rates (EIRs) from one infectious bite per person per year (ibpppy) to 10 ibpppy] [11], and because the majority of the 61% of sub-Saharan Africans who live in rural areas experience an EIR more than 10 ibpppy (in addition to the fact that urban sub-Saharan Africans experience an average EIR >10 ibpppy) [12], we evaluated a range of EIRs from 10 ibpppy to the previously estimated EIR of the Ugandan clinical study site of up to 562 ibpppy [13]. Finally, we assessed the epidemiological effectiveness of protease inhibitors on malaria burden under varying newborn HIV prevalence and varying malaria transmission intensities. We found that in areas where HIVand malaria are coendemic, the extended posttreatment prophylactic effect of artemether-lumefantrine in the context of protease inhibitor based regimens is a significant benefit that should be factored into the decision regarding the selection of first-line antiretroviral therapy treatment to prescribe in malaria coendemic regions.

Materials and methods

To estimate the effectiveness of the extended posttreatment prophylactic effect of artemether-lumefantrine in reducing the health burden of recurrent malaria in the setting of protease inhibitor-based HAART, we developed a dynamic model of malaria transmission in sub-Saharan Africa.

From a Ugandan clinical study, data were obtained comparing the incidence of uncomplicated malaria in HIV-infected children on protease inhibitor based vs. NNRTI-based regimens [5]. On the basis of these data, we constructed distributions for the duration of the posttreatment prophylactic effect (for preventing recurrent malaria) of the antimalarial drug, lumefantrine, with and without protease inhibitors (Figure S2, http://links.lww.com/QAD/A618). From the distributions on the posttreatment prophylactic effect of lumefantrine, we further derived how long protease inhibitors extend the duration of the posttreatment prophylactic effect (Figure S2, http://links.lww.com/QAD/A618).

The outcomes measured, for all HIV-positive and HIV-negative children, include annual malaria incidence, malaria transmission intensity (as measured by the EIR) and disease burden measured through disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs). DALYs for a disease are the combined sums of both the years of life lost due to premature mortality and the years lost due to disability over an entire population [14].

We conservatively determined the health benefit of protease inhibitor based HAART only with respect to malaria, and only with respect to the extended posttreatment prophylactic effect derived from the combination of protease inhibitor based HAART and artemether-lumefantrine, and do not consider any HIV-related benefit associated directly with the choice of HAART regimen.

To reflect the varying malaria transmission intensity and varying newborn HIV prevalence levels that occur in different locations across sub-Saharan Africa, we considered EIR ranging from 10 to 562 ibpppy, and newborn HIV prevalence ranging from 0.01 to 6.7% [2,15]. We limited our EIR range to a maximum of 562 ibppy due to concerns of overstating effects of protease inhibitor based HAART at higher EIRs, as well as a recognition that the overwhelming majority of sub-Saharan Africa is situated in EIR ranges below this threshold [16]. To reflect varying availability of protease inhibitors in sub-Saharan Africa, we varied the proportion of children who are treated with NNRTI and protease inhibitor based HAART from 0 to 1 in intervals of 0.1.

Mathematical model

We developed a dynamic model that couples malarial infection dynamics of humans and mosquitoes parameterized from the epidemiological and clinical studies, including a recent clinical trial in Uganda [5]. The population size of mosquitoes determines malaria transmission intensity, that is the average number of infectious mosquitoes bites received per child. We divided the mosquito population into three compartments, Ms susceptible adult, ME exposed adult and MI infected adults. We assumed the total mosquito population M to be constant such that M = MS+ME+MI. Mosquito demography was parameterized from an entomological study of Anophelis gambiae [17]. We denoted τM as the duration of extrinsic incubation of malaria in mosquitoes, c as the biting rate of the mosquitoes, I+ as the number of malaria-infected children who are also HIV-infected and I− as the malaria-infected children who are HIV-negative. The probability of malaria transmission to a mosquito, βH (I+ + I−)/H, was the product of the probability of a mosquito becoming infectious upon biting an infected human, βH, and the proportion of infected children, where H is the total number of humans. The force of infection for the mosquito population was given by:

The child population was divided into an HIV-infected group, which was indicated by a + superscript and an HIV-negative group represented by a – superscript. We considered that all newborns Rm have maternally acquired immunity against malaria that wanes at a rate δM. The rate at which a susceptible individual S acquires infection was given by the force of infection:

Children who recovered from malaria did so at the rate γ. The rate at which a recovered child becomes susceptible again, that is the rate at which the posttreatment prophylactic effect of artemether-lumefantrine wanes, was denoted by δ. We take into account that protease inhibitors extend the posttreatment prophylactic effect of artemether-lumefantrine, likely due to protease inhibitor mediated inhibition of lumefantrine metabolism [10]. Parameter values, associated distributions and sources are provided in Table 1 [14,19–33]. Model equations are presented in the Webappendix.

Table 1.

Parameter values and associated distributions.

| Symbol | Parameter | Base | Distribution | Ref | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/d0 | Mean old adult mosquito life span | 7.6 days | logN (1.98, 0.31) | [18] | ||

| 1/τM | Extrinsic incubation rate | 0.10533 days−1 | N (0.10533, 0.011) | [19] | ||

| c | Mosquito biting rate | 1/3 days−1 | Fixed | [20] | ||

| bH | Birth rate of humans | 0.046 year−1 | Fixed | [21] | ||

| dH | (natural) Death rate of humans | 0.013 year−1 | Fixed | [21] | ||

| 1/δm | Mean duration of maternal immunity | 60 days | Fixed | [18] | ||

| 1/δ | Mean duration of posttreatment prophylactic effect | 28 days | Fixed | |||

| 1/γ | Mean duration of malaria infection recovery | 28 days | U (21,35) | [22] | ||

| μ | % increase in malaria incidence due to HIV | 0.0255 | Fixed | [23] | ||

|

|

Mosquito to human (HIV negative) transmission probability | 0.25 | N (0.25, 0.04) | [24] | ||

|

|

Mosquito to human (HIV positive) transmission probability |

|

Fixed | |||

| βH | Human to mosquito transmission probability | 0.43 | Beta (12.5, 16.35) | [25] | ||

| th | Transition out of <5 age group | 1/1825 | Fixed | |||

| ω | Proportion reporting for treatment to a healthcare setting | 0.618 | Beta (65.40, 40.42) | [26] | ||

| αMIN | Minimum estimated HIV prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa (newborns) | 0.01% | Table S1, http://links.lww.com/QAD/A618 | |||

| αavg | Average estimated HIV prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa (newborns) | 1.3% | Table S1, http://links.lww.com/QAD/A618 | |||

| αMAX | Maximum estimated HIV prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa (newborns) | 6.7% | Table S1, http://links.lww.com/QAD/A618 | |||

| 1/δPI | Duration of extended posttreatment prophylactic effected | 19.75 days | See Figure S2, http://links.lww.com/QAD/A618 | |||

| δben | DALY discount rate | 0.03 | [14] | |||

| Depisode | Disability weight (malaria episode) | 0.2078 | [14] | |||

| Ds | Disability weight (severe malaria episode) | 0.443 | [27] | |||

| DN | Disability weight (neurological sequelae) | 0.471 | [14] | |||

| DA | Disability weight (severe malaria anaemia) | 0.012 | [14] | |||

| DNA | Disability weight (neurological sequelae and anaemia) | 0.483 | [14] | |||

| Ddeath | Disability weight (death) | 1.0 | [14] | |||

| Lepisode | Duration of malaria episode | 5.1 days | [28] | |||

| LS | Duration of severe malaria episode | 8.75 days | [27] | |||

| LC | Duration of cerebral malaria | 6.5 days | [27] | |||

| LN | Duration of neurological sequelae | 10.1 days | [29] | |||

| LA | Duration of anaemia | 11 days | [28] | |||

| LCA | Duration of cerebral malaria and severe malaria anaemia | 11 days | ||||

| LNA | Duration of neurological sequelae and severe malaria anaemia | 11 days | ||||

| Ldeath | Years of life lost in death | 55 years | [30] | |||

| ξS | Risk of developing severe malaria given malaria infection | 0.0057 | [31] | |||

| ξC | Risk of developing (only) cerebral malaria (CM) given severe malaria infection | 0.002 | [31] | |||

| ξA | Risk of developing (only) severe malarial anaemia (SMA) given severe malaria infection | 0.0171 | [31] | |||

| ξCA | Risk of developing CM and SMA given severe malaria infection | 0.00096 | [31] | |||

| ξN | Risk of developing neurological sequelae given CM | 0.098 | [29] | |||

| αN | Risk of death due to neurological sequelae | 0.1835 | [32] | |||

| αA | Risk of death due to SMA | 0.097 | [32] | |||

| αC | Risk of death due to CM | 0.192 | [31] | |||

| αCA | Risk of death due to CM and SMA | 0.347 | [33] | |||

| αNA | Risk of death due to neurological sequelae and SMA | 0.1835 | [14] | |||

| Onset | Average age of malaria exposure | 2 months | ||||

| C̃ | Age-corrected constant | 0.1658 | [14] | |||

| B | Age-weighting parameter | 0.04 | [14] |

DALY, disability-adjusted life-year.

The entomological inoculation rate

The EIR is defined as the number of infectious bites on a human annually. The average EIR in urban settings in Africa has been estimated as 18.8 ibpppy and in rural settings as 112 ibpppy [11,16], with upper estimates at the Ugandan clinical study site of 562 ibpppy (observations ranged from 379 to 562 ibpppy) [5,13,34]. We consider EIR values over this range, varying the EIR from a low malaria transmission setting of 10 ibpppy to an intermediate EIR of 112 ibpppy estimated from several locations in sub-Saharan Africa [16], to the observed high malaria transmission intensity of the Ugandan clinical study site of 562 ibpppy (although more recent estimates have suggested a lower EIR at this site) [5,13,34]. Details pertaining to the EIR calculation are available in the Webappendix.

Health outcomes

To determine the direct and indirect benefit of protease inhibitor based HAART on death and disability due to malaria, we measured the health outcomes in DALYs [35], with a newborn HIV prevalence (α) corresponding to an estimated maximum newborn HIV prevalence of 6.7% (Table 1), the average newborn HIV prevalence of sub-Saharan Africa of 1.3% [36] and an estimated minimum newborn HIV prevalence of 0.01%. In addition, we varied the EIR to examine a lower rate of 10 ibpppy, the estimated average EIR of 112 ibpppy [16] and the highest EIR encountered at the Ugandan clinical study site of 562 ibpppy [13]. We calculated time-discounted DALYs lost to malaria, severe malaria, cerebral malaria, neurological sequelae and severe malarial anaemia over a duration of 5 years. To determine the net DALYs saved, total DALYs lost under the NNRTI-based HAART scenario were subtracted from the protease inhibitor based HAART scenario. Parameter values for the calculation of the DALYs are contained in Table 1.

Sensitivity analysis

To quantify the contribution of each model parameter to the variability of the outcome measures, we calculated the partial rank correlation coefficients (PRCCs) between the input and output variables [37]. Specifically, a positive PRCC implies that when the value of an input variable increases, the output variable increases, whereas a negative PRCC implies that an increase in an input variable decreases the output variable (Table S2, http://links.lww.com/QAD/A618). In addition, the magnitude of a PRCC is a measure of the contribution of an input variable to the uncertainty of an output variable. For this purpose, we used Latin Hypercube Sampling to draw input parameters from their probability distributions as summarized in Table 1.

Results

To determine the impact of the artemether-lumefantrine mediated extension of the posttreatment prophylactic effect of protease inhibitors on malaria incidence, we simulated malaria transmission with a dynamic model under nine scenarios of low, intermediate and high conditions of both HIV prevalence [36] and malaria transmission [13,16], respectively. We found that in the range of malaria transmission intensities in our model, the use of HIV protease inhibitors at the intermediate (1.3%) and high (6.7%) HIV prevalence scenarios significantly reduced malaria incidence and saved DALYs (Table 2).

Table 2.

Base annual malaria incidence, annual incidence averted/1000 c and annual disability-adjusted life-years saved/1000 people.

| Low HIV prevalence | Intermediate HIV prevalence | High HIV prevalence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EIR of 10 (base annual incidence) | 2.43 (95% CI 0.05–4.49) | 2.54 (95% CI 0.05–4.50) | 2.63 (95% CI 0.06–4.74) |

| EIR of 10 (annual incidence averted/1000 people) | 0.03a (95% CI 0.01–0.10) | 5.2 (95% CI 1.90–11.2) | 25.5 (95% CI 8.70–50.2) |

| EIR of 10 (annual DALYs saved/1000 people) | 0.002 (95% CI 0.001–0.004) | 0.22 (95% CI 0.10–0.56) | 1.04 (95% CI 0.48–2.7) |

| EIR of 112 (base annual incidence) | 4.87 (95% CI 2.82–6.94) | 4.88 (95% CI 2.82–6.94) | 4.88 (95% CI 3.10–6.75) |

| EIR of 112 (annual incidence averted/1000 people) | 0.08 (95% CI 0.04–0.15) | 10.3 (95% CI 6.97–16.46) | 51.8 (95% CI 37.1–76.7) |

| EIR of 112 (annual DALYs saved/1000 people) | 0.004 (95% CI 0.002–0.008) | 0.55 (95% CI 0.24–0.99) | 2.82 (95% CI 1.14–5.12) |

| EIR of 562 (base annual incidence) | 6.00 (95% CI 4.44–8.85) | 6.02 (95% CI 4.44–8.61) | 6.03 (95% CI 4.51–8.77) |

| EIR of 562 (annual incidence averted/1000 people) | 0.10 (95% CI 0.05–0.2) | 13.0 (95% CI 9.09–22.6) | 65.8 (95% CI 47.0–106.2) |

| EIR of 562 (annual DALYs saved/1000 people) | 0.006 (95% CI 0.003–0.01) | 0.8 (95% CI 0.4–1.6) | 4.3 (95% CI 1.70–7.91) |

CI, confidence interval; DALYs, disability-adjusted life-years; EIR, entomological inoculation rate.

Failure to reject the hypothesis that the population median is less than the sample median at the α = 0.05 significance level through the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Base annual incidence corresponds to 100% NNRTI HIV treatment. Model represents incidence and DALYs for all children, both HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected.

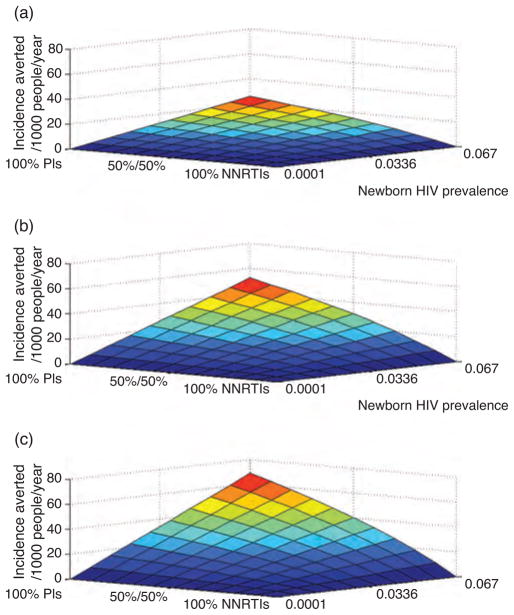

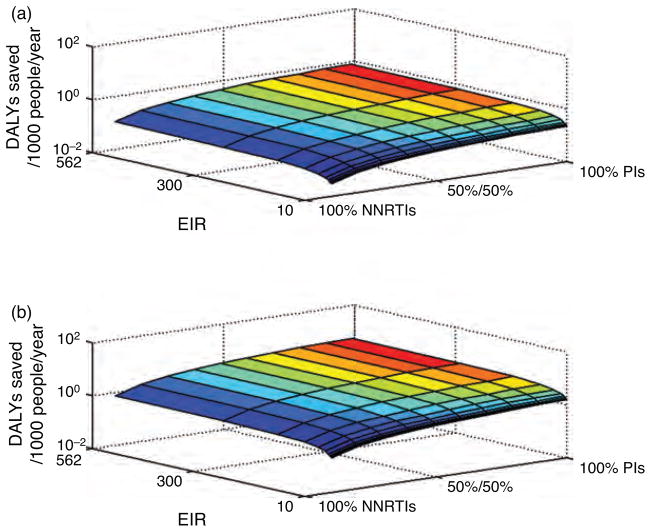

With an EIR of 10 ibpppy, and all the HIV-infected children treated with NNRTI-based HAART, under the scenarios of low (0.01%), intermediate (1.3%) and high (6.7%) newborn HIV prevalence, there were 2.43, 2.54 and 2.63 annual malaria incidence per person (Table 2). Switching HIV treatment from NNRTI-based HAART to protease inhibitor based HAARTaverted between 0.03 to 25.5 annual incidences of malaria per 1000 people, depending on the HIV prevalence (Table 2, Fig. 1). With respect to DALYs, the switching from NNRTI-based HAART to protease inhibitor based HAART saved 0.22 DALYs per 1000 people annually under intermediate HIV prevalence, and 1.04 DALYs per 1000 people annually for a scenario of high HIV prevalence (Table 2, Fig. 2). Considering the incidence averted only in HIV-infected children, for low (0.01%), intermediate (1.3%) and high (6.7%) newborn HIV prevalence, switching HIV treatment from NNRTI-based HAART to protease inhibitor-based HAARTaverted 278, 280 and 290 annual incidences of malaria per 1000 HIV-infected children.

Fig. 1. Annual incidences averted per 1000 people vs. newborn HIV prevalence and treatment.

EIR: Top 10 ibpppy, middle 112 ibpppy and bottom 562 ibpppy. Incidence averted is for all children, HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected.

Fig. 2. Disability-adjusted life-years saved per 1000 people/year vs. entomological inoculation rate and treatment.

The newborn HIV prevalence is top 1.3% and bottom 6.7%. DALYs saved is for all children, HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected.

For the average EIR encountered in sub-Saharan Africa of 112 ibpppy, when all HIV-infected children are treated with NNRTIs, the annual malaria incidence per person annually over low (0.01%), intermediate (1.3%) and high (6.7%) newborn HIV prevalence was close to 4.88 (Table 2). A switch to the protease inhibitor-based HAART averted a range of 0.08 to 51.8 cases of malaria per 1000 people, depending on the newborn HIV prevalence (Table 2). Annual DALYs saved per 1000 people ranged from 0.55 to 2.82, respectively, for the intermediate and high newborn HIV prevalence scenarios (Table 2, Fig. 2). Considering the impact upon only HIV-infected children, under low (0.01%), intermediate (1.3%) and high (6.7%) newborn HIV prevalence, switching to protease inhibitor-based HAART averted, 842, 843 and 847 annual incidences of malaria per 1000 HIV-infected children.

For the EIR of the Ugandan clinical study site of 562 ibpppy, when HIV-infected children are treated with NNRTIs, the annual malaria incidence per person (for newborn HIV prevalence of 0.01, 1.3 and 6.7%) was close to 6 (Table 2). Using protease inhibitor based HAART averts between 0.10 to 65.8 cases of malaria per 1000 people, depending on HIV prevalence (Fig. 1). Using protease inhibitor based HAART saved 0.8 and 4.3 DALYs per 1000 people annually for the intermediate and high newborn HIV prevalence scenarios, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 2). With respect to HIV-infected children, for low (0.01%), intermediate (1.3%) and high (6.7%) newborn HIV prevalence, switching HIV treatment to protease inhibitor based HAART averted 1042, 1043 and 1043 annual incidences of malaria per 1000 HIV-infected children.

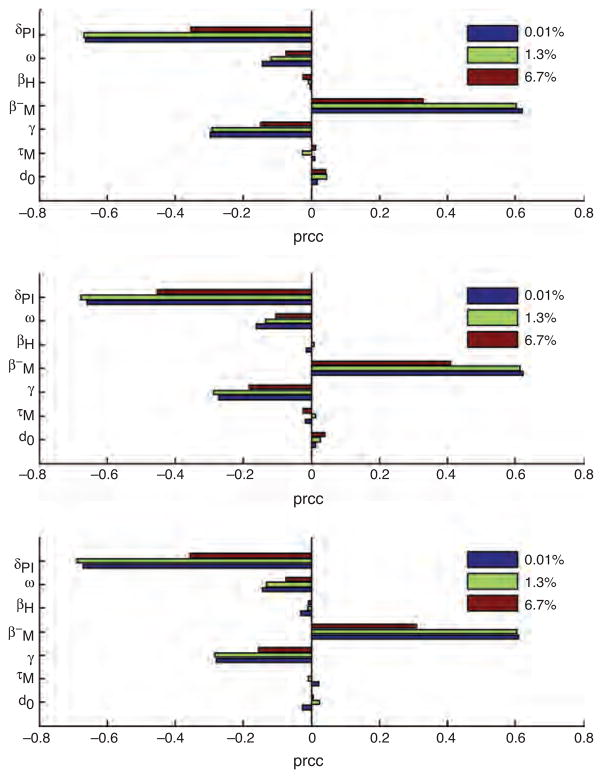

Sensitivity analysis showed that for all scenarios of HIV prevalence and malaria transmission intensities, the primary parameters that determine malaria incidence were mosquito to human transmission (βM) and the duration of posttreatment prophylactic effect (δPI) (Fig. 3). As both the malaria transmission intensity and HIV prevalence increase, the sensitivity of the projections of the posttreatment prophylactic effect (δPI) also increases (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Partial rank correlation coefficients, where (1/δPI) is the duration of the extended posttreatment prophylactic effect, (ω) is the proportion reporting for treatment to a healthcare setting, (βH) is the human to mosquito transmission probability, (βH−) is the mosquito to human (HIV-negative) transmission probability, (1/γ) is the mean duration of malaria infection recovery, (τM) is the extrinsic incubation rate and (d0) is the mean old adult mosquito life span.

Partial rank correlation coefficients (PRCCs). EIRs for top, middle, and bottom panel are 10, 112, and 562 ibppy, respectively. Parameters were considered to be important in reducing incidence of malaria if their |PRCC| > 0.4. Significance tests assessed if PRCCs were significantly different from zero (see Table S2, http://links.lww.com/QAD/A618).

Discussion

Our transmission modelling analysis predicts that the use of protease inhibitor based regimens in the setting of artemether-lumefantrine treatment would substantially reduce the health burden of malaria in HIV-infected sub-Saharan African children. Treating HIV-infected children with protease inhibitors achieves a reduction in annual malaria incidence, saves DALYs and lowers annual number of infectious bites per person. With the reduction in malaria transmission that occurs, there would also be an indirect impact on the incidence of malaria to the population overall, even to individuals who are not themselves treated or HIV infected.

The predictions of our model are in line with observed clinical data and intervention studies [38]. Our predicted 6 annual malaria incidence per person for an EIR of 562 ibpppy is within the empirical range of 3.5–6.5 observed at the clinical study site in Tororo, Uganda, for HIV-uninfected children [34]. Because we only measured the benefit of protease inhibitors, our model’s predicted annual malaria incidence per person for HIV-infected children was above the incidence levels from the Ugandan clinical study [5]. This is due, in part, to compounding protective factors in the Ugandan clinical study, such as the significant antimalarial benefit that all HIV infected children received from the antimicrobial, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole [39]. In addition, the clinical study on the effect of protease inhibitors on malaria incidence determined that HIV-infected children treated with protease inhibitor-based HAARTendure 0.93 less annual malaria incidence per person [5] in comparison to their NNRTI-based HAART counterparts. Using the previously estimated EIR of 562 ibpppy from the clinical study site [13], our model predicts that HIV-infected children treated with protease inhibitor-based HAART endure 278–1043 less annual malaria incidence per 1000 HIV infected people in comparison to their NNRTI-based HAART counterparts. Furthermore, our model’s predictions of 0.002–4.3 annual DALYs saved per 1000 children are comparable to alternative studies on the benefit of protease inhibitor-based HAART for the prevention of malaria that predict 2.15 annual DALYs saved per 1000 children [40].

The annual DALYs saved, as a result of the indirect benefit of treating HIV-infected children with protease inhibitor-based HAART, is substantial and comparable to direct malaria interventions, such as the intermittent presumptive treatment of malaria in pregnancy [41]. Our analysis was conservative in that we focused on the impact of an HIV protease inhibitor-mediated extension of the lumefantrine posttreatment prophylactic effect in the context of artemether-lumefantrine treatment. However, emerging data suggest that protease inhibitor-based HAART may have additional benefits on malaria, including activity against gametocytes and transmission-blocking activity [42,43]. In addition, in contrast to the extension of prophylactic activity seen with lopinavir-ritonavir, the use of artemether-lumefantrine in the setting of efavirenz-based HAART is associated with a significant reduction in lumefantrine exposure [44,45]. A further benefit of switching from NNRTIs to protease inhibitors is that protease inhibitors have been found to provide a higher barrier to the development of drug-resistance in HIV [8].

Increasing evidence supports the efficacy of protease inhibitor-based HAART in the treatment of HIV-infected children and adults in Africa [4,8,46,47]. Our model suggests an additional benefit on the prevention of malaria at any level of malaria transmission, though the magnitude of the marginal benefit of protease inhibitors for a community is sensitive to the level of endemic malaria in a particular setting. Consequently, protease inhibitors may be deemed both effective and cost-effective in settings with high intensities of malaria and less worthwhile in settings of lower intensity, given inevitable budgetary constraints. For example, areas, such as much of Uganda, burdened with devastating coepi-demics of malaria and HIV would benefit most dramatically from the switch to protease inhibitors, whereas the marginal benefits of protease inhibitors for urban settings in which malaria tends to be less prevalent would be less impactful.

Mathematical models of real-world infectious diseases inevitably involve simplifications. For example, in our analysis, we did not account for multiple malaria strains, vector subspecies, potential impacts upon gametocyte rates or independent effects of other prevention measures. For example, as both HAART groups were receiving trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis, we were unable to discern the independent effects of trimetho-prim-sulfamethoxazole on the risk of recurrent malaria. Future models may attempt to model this effect using data from other African populations receiving prophylaxis in the absence of HAART. With respect to HIV, the higher genetic barrier to drug resistance would likely tip the balance further in the direction of protease inhibitors over NNRTIs. Our model is calibrated specifically to describe transmission of the most virulent malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum. However, malaria species such as Plasmodium vivax are also treated with artemether-lumefantrine, and protease inhibitors have been shown to have similarly strong in-vitro direct antimalarial effects [48,49]. Although clinical data on HAART and artemether-lumefantrine are lacking, modest adjustments to our model parameterization could help to predict potential benefits of this regimen in coendemic settings.

In summary, HIV-infected children that use protease inhibitor based HAART have a reduced burden of malaria due to extended postprophylactic effect of artemether-lumefantrine. Our model shows that the extended postprophylactic effect of artemether-lumefantrine would effectively reduce malaria incidence and prevalence of HIV-infected children on protease inhibitors from intermediate to high HIV prevalence levels. Consequently, in settings in which artemether-lumefantrine is the principal ACT used in the treatment of malaria, protease inhibitor based HAART may be a preferred regimen for HIV treatment in coendemic settings.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the MU-UCSF Research Collaboration, and particularly Dr Moses Kamya and Dr Jane Achan for access to clinical data on the time to next infection from the recently published trial [5]. We would also like to thank the PROMOTE study team and participants in Tororo, Uganda. In addition, we are also grateful for the editorial input of Angelika Hofmann.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health [grant number MIDAS U01 GM087719] and [grant number 5R01HD068174].

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors do not have either a commercial or other association that might pose a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Flateau C, Le Loup G, Pialoux G. Consequences of HIV infection on malaria and therapeutic implications: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:541–556. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bositis CM, Gashongore I, Patel DM. Updates to the World Health Organization’s recommendations for the use of anti-retroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants. Med J Zambia. 2010;37:111–117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. Consolidated ARV guidelines 2013. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Violari A, Lindsey JC, Hughes MD, Mujuru HA, Barlow-Mosha L, Kamthunzi P, et al. Nevirapine versus ritonavir-boosted lopinavir for HIV-infected children. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2380–2389. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Achan J, Kakuru A, Ikilezi G, Ruel T, Clark TD, Nsanzabana C, et al. Antiretroviral agents and prevention of malaria in HIV-infected Ugandan children. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2110–2118. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tejerina F, Bernaldo de Quirós JCL. Protease inhibitors as preferred initial regimen for antiretroviral-naive HIV patients. AIDS Rev. 2011;13:227–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO. Antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection in infants and children: towards universal access: recommendations for a public health approach: 2010 revision. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [accessed 6 November 2013]. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js18809en/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuhn L, Hunt G, Technau K-G, Coovadia A, Ledwaba J, Pickerill S, et al. Drug resistance among newly diagnosed HIV-infected children in the era of more efficacious antiretroviral prophylaxis. AIDS. 2014;28:1673–1678. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parikh S, Gut J, Istvan E, Goldberg DE, Havlir DV, Rosenthal PJ. Antimalarial activity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49 :2983–2985. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.7.2983-2985.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.German P, Parikh S, Lawrence J, Dorsey G, Rosenthal PJ, Havlir D, et al. Lopinavir/ritonavir affects pharmacokinetic exposure of artemether/lumefantrine in HIV-uninfected healthy volunteers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;51:424–429. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181acb4ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hay SI, Guerra CA, Tatem AJ, Atkinson PM, Snow RW. Urbanization, malaria transmission and disease burden in Africa. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:81–90. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carneiro I, Smith L, Ross A, Roca-Feltrer A, Greenwood B, Schellenberg JA, et al. Intermittent preventive treatment for malaria in infants: a decision-support tool for sub-Saharan Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:807–814. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.072397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okello PE, Van Bortel W, Byaruhanga AM, Correwyn A, Roelants P, Talisuna A, et al. Variation in malaria transmission intensity in seven sites throughout Uganda. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:219–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray C, Lopez A. The global burden of disease: a comprehensive assessment of mortality and disability from diseases, injuries, and risk factors in 1990 and projected to 2020. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO. Global update on HIV treatment 2013: results, impact and opportunities. Geneva: WHO; 2013. [accessed 15 November 2013]. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/progressreports/update2013/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kelly-Hope LA, McKenzie FE. The multiplicity of malaria transmission: a review of entomological inoculation rate measurements and methods across sub-Saharan Africa. Malar J. 2009;8:19. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-8-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Afrane YA, Zhou G, Lawson BW, Githeko AK, Yan G. Life-table analysis of Anopheles arabiensis in western Kenya highlands: effects of land covers on larval and adult survivorship. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:660–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Griffin JT, Hollingsworth TD, Okell LC, Churcher TS, White M, Hinsley W, et al. Reducing Plasmodium falciparum malaria transmission in Africa: a model-based evaluation of intervention strategies. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ijumba JN, Mwangi RW, Beier JC. Malaria transmission potential of Anopheles mosquitoes in the Mwea-Tebere irrigation scheme, Kenya. Med Vet Entomol. 1990;4:425–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1990.tb00461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lines JD, Wilkes TJ, Lyimo EO. Human malaria infectiousness measured by age-specific sporozoite rates in Anopheles gambiae in Tanzania. Parasitology. 2009;102:167. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000062454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. . World population prospects: The 2010 revision, Volume 1: Comprehensive Tables. New York: UN; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith DL, Drakeley CJ, Chiyaka C, Hay SI. A quantitative analysis of transmission efficiency versus intensity for malaria. Nat Commun. 2010;1:108. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korenromp EL, Williams BG, de Vlas SJ, Gouws E, Gilks CF, Ghys PD, et al. Malaria attributable to the HIV-1 epidemic, sub-Saharan Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1410–1419. doi: 10.3201/eid1109.050337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Filipe JAN, Riley EM, Drakeley CJ, Sutherland CJ, Ghani AC. Determination of the processes driving the acquisition of immunity to malaria using a mathematical transmission model. PLoS Comput Biol. 2005;3:e255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davidson G, Draper C. Field studies of some of the basic factors concerned in the transmission of malaria. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1953;47:522–535. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(53)80005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindblade KA, O’Neill DB, Mathanga DP, Katungu J, Wilson ML. Treatment for clinical malaria is sought promptly during an epidemic in a highland region of Uganda. Trop Med Int Health. 2000;5:865–875. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2000.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Briét OJT, Penny MA, Hardy D, Awolola TS, Van Bortel W, Corbel V, et al. Effects of pyrethroid resistance on the cost effectiveness of a mass distribution of long-lasting insecticidal nets: a modelling study. Malar J. 2013;12:77. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Snow RW, Craig MH, Newton CR, Steketee RW. Working Paper No. 11, Disease Control Priorities Project. Bethesda, MD: Fogarty International Center, National Institutes of Health; 2003. The public health burden of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Africa: deriving the numbers. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brewster DR, Kwiatkowski D, White NJ. Neurological sequelae of cerebral malaria in children. Lancet. 1990;336:1039–1043. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92498-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roca-Feltrer A, Carneiro I, Armstrong Schellenberg JR. Estimates of the burden of malaria morbidity in Africa in children under the age of 5 years. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:771–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murphy SC, Breman JG. Gaps in the childhood malaria burden in Africa: cerebral malaria, neurological sequelae, anemia, respiratory distress, hypoglycemia, and complications of pregnancy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2001;64:57–67. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2001.64.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perkins DJ, Were T, Davenport GC, Kempaiah P, Hittner JB, Ong’echa JM. Severe malarial anemia: innate immunity and pathogenesis. Int J Biol Sci. 2011;7:1427–1442. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7.1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olliaro P. Editorial commentary: mortality associated with severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria increases with age. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:158–160. doi: 10.1086/589288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jagannathan P, Muhindo MK, Kakuru A, Arinaitwe E, Greenhouse B, Tappero J, et al. Increasing incidence of malaria in children despite insecticide-treated bed nets and prompt anti-malarial therapy in Tororo, Uganda. Malar J. 2012;11:435. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murray CJ. Quantifying the burden of disease: the technical basis for disability-adjusted life years. Bull World Health Organ. 1994;72:429–445. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.UNAIDS. [accessed 25 November 2013];Global HIV/AIDS response: epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access. 2011 http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/progress_report2011/en/

- 37.Blower SM, Dowlatabadi H. Sensitivity and uncertainty analysis of complex models of disease transmission: an HIV model, as an example. Int Stat Rev. 1994;62:229–243. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kakuru A, Achan J, Muhindo MK, Ikilezi G, Arinaitwe E, Mwangwa F, et al. Artemisinin-based combination therapies are efficacious and safe for treatment of uncomplicated malaria in HIV-infected Ugandan children. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59 :446–453. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandison TG, Homsy J, Arinaitwe E, Wanzira H, Kakuru A, Bigira V, et al. Protective efficacy of co-trimoxazole prophylaxis against malaria in HIV exposed children in rural Uganda: a randomised clinical trial. BMJ. 2011;342:d1617. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ahmed BS, Phelps BR, Reuben EB, Ferris RE. Does a significant reduction in malaria risk make lopinavir/ritonavir-based ART cost-effective for children with HIV in co-endemic, low-resource settings? Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2014;108:49–54. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trt108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morel CM, Lauer JA, Evans DB. Cost effectiveness analysis of strategies to combat malaria in developing countries. BMJ. 2005;331:1299. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38639.702384.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hobbs CV, Tanaka TQ, Muratova O, Van Vliet J, Borkowsky W, Williamson KC, et al. HIV treatments have malaria gametocyte killing and transmission blocking activity. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:139–148. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ikilezi G, Achan J, Kakuru A, Ruel T, Charlebois E, Clark TD, et al. Prevalence of asymptomatic parasitemia and gametocytemia among HIV-infected Ugandan children randomized to receive different antiretroviral therapies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88:744–746. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maganda BA, Minzi OMS, Kamuhabwa AAR, Ngasala B, Sasi PG. Outcome of artemether-lumefantrine treatment for uncomplicated malaria in HIV-infected adult patients on anti-retroviral therapy. Malar J. 2014;13:205. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-13-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang L, Parikh S, Rosenthal PJ, Lizak P, Marzan F, Dorsey G, et al. Concomitant efavirenz reduces pharmacokinetic exposure to the antimalarial drug artemether-lumefantrine in healthy volunteers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61 :310–316. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31826ebb5c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruel TD, Kakuru A, Ikilezi G, Mwangwa F, Dorsey G, Rosenthal PJ, et al. Virologic and immunologic outcomes of HIV-infected Ugandan children randomized to lopinavir/ritonavir or non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65:535–541. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paton NI, Kityo C, Hoppe A, Reid A, Kambugu A, Lugemwa A, et al. Assessment of second-line antiretroviral regimens for HIV therapy in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:234–247. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1311274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bassat Q. The use of artemether-lumefantrine for the treatment of uncomplicated Plasmodium vivax malaria. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lek-Uthai U, Suwanarusk R, Ruengweerayut R, Skinner-Adams TS, Nosten F, Gardiner DL, et al. Stronger activity of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 protease inhibitors against clinical isolates of Plasmodium vivax than against those of P. falciparum. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52:2435–2441. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00169-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.