Abstract

Methods to assess ecosystem services using ecological or economic approaches are considerably better defined than methods for the social approach. To identify why the social approach remains unclear, we reviewed current trends in the literature. We found two main reasons: (i) the cultural ecosystem services are usually used to represent the whole social approach, and (ii) the economic valuation based on social preferences is typically included in the social approach. Next, we proposed a framework for the social valuation of ecosystem services that provides alternatives to economics methods, enables comparison across studies, and supports decision-making in land planning and management. The framework includes the agreements emerged from the review, such as considering spatial–temporal flows, including stakeholders from all social ranges, and using two complementary methods to value ecosystem services. Finally, we provided practical recommendations learned from the application of the proposed framework in a case study.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13280-014-0555-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Social evaluation, Stakeholder, Ecosystem services flow, Ecosystem services ranking, Social perception

Introduction

The use of ecosystem services [the benefits humans receive from nature (Alcamo et al. 2003)] is becoming a powerful tool in land planning and management. According to the subject of study to be valuated, the study of ecosystem services can be approached from an ecological, economic, or social perspective. The ecological approach focuses on measuring ecological functions or ecosystem properties (de Groot et al. 2002); the economic approach estimates the use and non-use values of ecosystems in monetary terms (Wilson and Carpenter 1999); and the social approach is based on the values society attributes to each ecosystem service (Martín-López et al. 2012). However, the unclear existing methodology to assess ecosystem services from the social approach (Menzel and Teng 2010) is risking the potential impact of the ecosystem services framework in land planning and management (Chan et al. 2012a). For instance, the fringe between the economic and the social approach is not well distinguished, leading to the frequent use of econometric methods to assess social preferences on ecosystem services. In other instances, the social approach is only implemented to assess cultural ecosystem services, disregarding the rest of the services (such as regulating, supporting, and provisioning) (Newton et al. 2012; Plieninger et al. 2013). The omission of the other types of services in the social valuation of ecosystem services might be due, among other reasons, to the expertise and amount of time that these methods require, and to the usual confusion between the category of socio-cultural ecosystem services [i.e., “the nonmaterial benefits people obtain from ecosystems through spiritual enrichment, cognitive development, reflection, recreation, and aesthetic experiences” (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) 2005, p. 40] and the social approach of ecosystem services (which evaluates all ecosystem services).

In ecosystems management, social valuation has typically been implemented with the aim of achieving policy makers’ objectives [e.g., river restoration projects and water and natural-resource management (Menzel and Teng 2010)]. However, its potential can be extended further by including the participation of society in ecosystem services assessments advising decision-making (Chan et al. 2012a). This will more likely enable legitimate results and satisfactory decisions to more stakeholders (Menzel and Teng 2010). In turn, that will help to develop more resilient communities (Folke et al. 2002) built on social fulfillment and environmental sustainability (Castillo et al. 2005; Berkes and Turner 2006).

Developing a framework to guide social assessments of ecosystem services is a challenge where collaboration between social and natural scientists is required (Maass et al. 2005; Raymond et al. 2013). Yet to our knowledge, this challenge has not been addressed, and several approaches can be pursued. Here, we apply multiple disciplines that influence the expression of ecosystem services preferences by stakeholders (e.g., anthropology, sociology, and psychology), together with views of experts on ecosystem management to devise such a framework. We aim to use this as a common ground to share expertise across social assessments of ecosystem services, and to support land planning and management. As we will show in this article, such comparisons across studies are currently limited by incomparable spatial and temporal scales, disparate methods of evaluating ecosystem services, and especially by the different status of stakeholders involved.

The objectives of this paper are: (1) to explore how the social valuation of ecosystem services has been addressed to date in the scientific literature, (2) to propose a novel framework to guide social valuations of ecosystem services, and (3) to illustrate the proposed framework via a case study.

Methods

To develop a framework to guide social valuations of ecosystem services, we first explored how the social valuation of ecosystem services has been addressed to date through an in-depth literature review; secondly, we proposed a framework including aspects that emerged from the review; and thirdly, we implemented the proposed framework in a case study. Below, we describe the methods used in each part.

Current trends in the social valuation of ecosystem services

To comment on the current trends relative to the social valuation of ecosystem services and to identify why this approach remains unclear, we reviewed all articles found across all type of sources (i.e., journals, conference proceedings, and books or book chapters) indexed in the ISI Web of Knowledge (which included the Web of Science, Medline, Zoological Records, and the Journal of Citation databases) published before the end of September 2013, that contained the keywords “ecosystem services,” and either the keywords “social valuation,” “preferences,” or “stakeholders” in the title or topic. We obtained a total of 1082 records (214, 328, and 540 records in each search, respectively). We checked their suitability by reading the title and abstract, or reading the article in full. After rejecting double-counting papers, records not published in English, papers that did not explicitly undertake a social evaluation of ecosystem services (for example, papers proposing methods, frameworks, or reviews), and papers assessing social preferences on ecosystem services solely by economic methods, 55 records remained (see the list of selected papers in Electronic Supplementary Material, S1). The remaining articles were carefully read, and the targeted information was extracted to calculate percentages of each aspect addressed.

A framework for the social assessment of ecosystem services

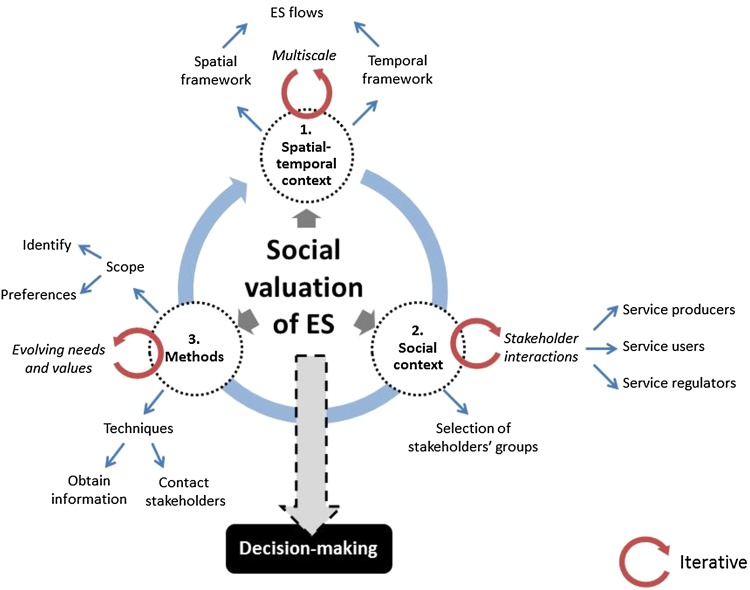

To develop a framework to guide social assessments of ecosystem services, we focused on the basic questions required: Who should complete the evaluation?, How to focus it?, At what extent?, etc. We incorporated each question as a stage in the assessment that can be more thoroughly examined if taken as an iterative process (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Framework for the social valuation of ecosystem services (ES). According to time and funding availability, all stages can be used in an iterative process to help decision-making. In the first stage, the spatial–temporal context is first broadly defined, and is then expanded to a multiscale assessment in second or successive rounds. In the second stage, the stakeholders selected to represent the social context can be more exhaustively detailed to identify the interactions among them. In the third stage, the appropriate method can be iteratively applied to reflect evolving preferences and views

Stage 1: The spatial and temporal context

Once we have elucidated the aim of the project—what is to be assessed—delimiting the spatial and temporal boundaries is the first step toward evaluating ecosystem services (Hein et al. 2006; Chan et al. 2012a). Ideally, the study area should be extended to include the causes and effects on the object of study, but in practice, it is sufficient to limit it to the timespan and territories that influence both the biophysical and the sociological dimensions the most. Since the appreciation of ecosystem services hinges on stakeholders’ dependence and their preferences might change over time and across spatial scales (Alcamo et al. 2003; Turner et al. 2003; Hein et al. 2006; Lamarque et al. 2011), a multiscale assessment of ecosystem services is valuable (Trabucchi et al. 2013). This process might increase the complexity of the evaluation, but capturing a greater variety of opinions and interactions among stakeholders and the ecosystem also increases knowledge concerning the decision context and enables the adaptation of management policies to each spatial and temporal scale (Hauck et al. 2013).

Stage 2: The social context

Who should evaluate ecosystem services? Ideally, all stakeholders of the project [i.e., the population that has a real influence on the object of study, or that might be affected by decisions made concerning it (Freeman 2010)] should participate (Satz et al. 2013). Stakeholders’ opinions can be requested from a single person, a sample of citizens, and the involvement of the total population (Antunes et al. 2009). More practically, stakeholders are usually grouped to ultimately include a small fraction of them (i.e., the key players; Chan et al. 2012a). Stakeholders that are required to express their opinions can be clustered by a myriad of criteria (age, sex, place of residence, profession, education, economic level, and political or religious beliefs), of which each might assign different values to ecosystem services (Cowling et al. 2008) depending on their views and needs (Vermeulen and Koziell 2002). As the social valuation of ecosystem services is intended to guide decision-making on ecosystem services management, it might be more convenient to group stakeholders according to their use of the ecosystem (e.g., irrigators, walkers, and conservationists) and their role in the government and social life of the area. With a good representation of stakeholders, outcomes are more likely to represent the actual values of the targeted area, avoiding trends of what are important ecosystem services to evaluate (Castillo et al. 2005; Escalera Reyes 2011; Moreno et al. 2014).

Stage 3: The methods for social assessment

Methods to elicit social preferences are varied, and depend on the scope of the study. Most studies focus on identifying valuable ecosystem services of an area (Maass et al. 2005), others aim to rank the importance of such services (Garcia-Llorente et al. 2012), and some reflect evolving human preferences and views through time (Aretano et al. 2013). Choosing a particular method might influence the results, but combining several methods according to our objectives might capture opinions from a broader spectrum, avoiding possible bias. In general, qualitative methods (see Chan et al. 2012a) are more useful for assessing ecosystem services because they enable a comprehensive understanding of the interactions between humans and the ecosystem (Daniel et al. 2012). Moreover, the most effective way to contact stakeholders and the methods used to analyze their responses are also important matters, the choice of which depends on the type of stakeholder approached.

In addition, considering ecosystems from the perspective of each stakeholder or beneficiary (Ringold et al. 2013) makes it easier to differentiate between the valuation of the service (what is supplied to the beneficiary) and the value given to it [what is weighted by the beneficiary (Tallis et al. 2012)]. Furthermore, a previous understanding of the reasons why an ecosystem service is valued is essential for comparing valuation outcomes across studies (see examples of typologies of values in Hein et al. 2006; Anthony et al. 2009; and Chan et al. 2012b).

Implementing the framework in a case study: The River Piedra floodplain

To illustrate the implementation of the framework proposed, we undertook a social valuation of the ecosystem services of the River Piedra floodplain (Spain). In this case study, we aimed to analyze whether the different perceptions of ecosystem services among stakeholder groups were related to their use of the ecosystem—were related to their main economic and leisure activities.

Spatial and temporal context

The spatial boundary was limited to the floodplain of the River Piedra (19.3 km2), a homogeneous area where the inhabitants depend on the riparian ecosystem for daily activities such as farming, nature tour operators, or visiting a natural waterfall park. The interviews provided information about the ecosystem services flows in the area over the last 50 years, but the ranking of ecosystem services preferences was based on the present. However, defining the temporal framework in the present was not easy to clarify; instead of ranking ecosystem services independently of what is currently delivered, some stakeholders ranked their preferences according to their perception of what is being currently delivered. To ensure consistency, these latter responses were rejected.

Social context

From a total population of 880, we contacted 71 people in person, including permanent and temporal residents, farmers, tour operators (hosting or guiding nature tourists), nature protection agents, scientists, and technicians working on riverbank restoration projects. Some of these people, such as local mayors and regional1 authorities, were contacted because of their relevant social role in decision-making, and in influencing perceptions about the river and the floodplain (i.e., local pro-environmental associations).

Methods of assessment

We performed semi-structured interviews for a qualitative sample of the main stakeholders of the River Piedra floodplain. Interviews were mostly held individually and occasionally in groups of two or three people from the same stakeholder sector (namely, when new stakeholders were contacted on site) and lasted from 30 to 90 min. Digital records of interviews were kept with the interviewees’ agreement. A minimum number of seven people from each of the main stakeholder sectors were interviewed; until we did not receive more information from the same sector of stakeholders (Valles 1999). This method maximizes the survey effort by obtaining a wide range of different answers. We were interested in both ecosystem services identification and preference rankings. Therefore, in the first part of the interview, we asked about the uses, products, and benefits that the interviewees derived from the River Piedra and how these had changed over the last 50 years. In the second part, we provided the interviewees with a list of 21 benefits derived from the River Piedra and asked them to rank the services according to what they considered more important for maintaining their standard of living (see the list of cards in Electronic Supplementary Material, S2).

Results

The first section shows the results of the review, organized according to the stages of the framework proposed. In the second section, we roughly explain the outcomes obtained from the implementation of the proposed framework in the River Piedra case study.

Current trends in the social valuation of ecosystem services

Stage 1

Spatial framework: The results of our review showed that most evaluations (40.6 %) occurred at a supra-local scale, larger than the municipality (i.e., county, province). The rest of spatial scales were addressed in a downscaling order as follows: region (a continent or a part of one) (1.6 %), state or country (3.1 %), small islands (3.1 %), watershed or valley (20.3 %), municipality (29.7 %), and farm (1.6 %) (Fig. 2a). In addition, the most-studied ecosystems (classification based on the MEA 2005) were cultivated (34.6 %), forest (24.7 %), inland water (11.1 %), dryland (8.6 %), mountain (7.4 %), coastal (6.2 %), island (3.7 %), and urban systems (3.7 %). Studies considering marine and polar ecosystems were not found in our review.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of valuations accomplished on different a spatial and b temporal scales. Note that in a supra-local refers to a scale larger than municipality (i.e., a county or province) and regional refers to a continent or a part of one

Temporal framework: Eighty percent of studies focused on current service provision, whereas only 9 % were based on a comparison between past and current provision, and 7.2 % compared present and future expectations (Fig. 2b). Finally, 1.8 % of studies projected future ecosystem service provision, and another 1.8 % compared the provision of services across past, present, and future ecosystem services scenarios.

Stage 2

Social context: From our review, 38.3 % of the studies considered the opinions of local residents, 25.2 % consulted local or regional2 representatives (including mayors, NGOs, and major associations), and 17.8 % included environmental professionals such as scientists and technicians. National authorities were considered in 9.4 % of the studies, and 7.5 % included the views of visitors or tourists (Fig. 3). Thirty-eight percent of studies were based exclusively on a single stakeholder group; namely, 29 % of studies were addressed to local inhabitants, 5.5 % to local or regional representatives, and 3.6 % to experts. No study relied solely on the opinion of national authorities, and the rest considered a mixture of several types of stakeholders. A small number of studies compared views between two stakeholder groups, for example, locals versus visitors, landowners versus tenants, and permanent residents versus seasonal ones.

Fig. 3.

Social context: percentage of types of stakeholders asked to evaluate ecosystem services. Note that local–regional representatives include mayors, NGOs, and major associations of a county or province; and experts refers to environmental professionals (scientists and technicians)

Stage 3

Scopes: Our review revealed two scopes for evaluating ecosystem services, and both were used equally: 34.5 % of the evaluations focused on identifying ecosystem services (asking participants to elaborate a list of services to test their environmental knowledge), 34.5 % focused on establishing preferences among ecosystem services (asking participants to sort ecosystem services according to their priorities), 27.3 % of the studies considered both scopes, and 3.6 % used social evaluation to elicit uniquely cultural services (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Percentage of each method used a as scope, b to analyze the social valuation of ecosystem services, and c to approach stakeholders. Abbreviations: a Id for Identify; Pref for Preferences, b MCDA for Multi-Criteria Decision Aid. Note that in a asterisk includes only cultural services; in b community mapping includes only those studies using this technique to identify ecosystem services; therefore, the percentage of published articles about mapping ecosystem services might be much greater; outcomes refers to both focus groups and workshop results; economic refers to the percentage of articles using economic methods as a social valuation of ecosystem services (i.e., calculated separately from the other percentages); in c focus group also includes workshops

Techniques: In our review, 34.3 % of the studies used discourse analysis, 27.1 % used Likert-type scales [a measure of the level of agreement or disagreement to a statement according to a symmetric scale; e.g., 1–5, 0–3, 0–10 (Likert 1932)], 22.9 % used ranking or weighting [including AHP (Analytical Hierarchy Process) (Saaty 1980) and swing-weighting], 8.6 % used Multi-Criteria Decision Aid [MCDA (Belton and Stewart 2001)], 5.7 % used community mapping, and 1.4 % used outcomes from a workshop or focus group (Fig. 4b). However, the majority of studies were based on a single methodology; primarily, discourse analysis (24 %), the Likert-type scale (24 %), and ranking or weighting (13 %). The combination of discourse analysis and ranking or weighting was used in 11 % of studies. Additionally, 16.4 % of the valuations included some type of economic valuation. Finally, our review showed that almost half of the valuations (46.8 %) included interviews (97 % were held face-to-face), 29 % organized workshops or focus groups, and 22.6 % distributed surveys (including face-to-face and by mail) (Fig. 4c). Eighty percent of studies were based exclusively on a single approach; namely, 35 % of the valuations were accomplished uniquely through face-to-face interviews, 22 % through surveys, and 22 % as workshops or focus groups. A minority of the valuations (1.6 %) were completed entirely by an expert panel and by e-mail, and the rest considered a mixture of techniques.

Case study: The social assessment of ecosystem services in the River Piedra floodplain

Identifying ecosystem services and flows: Stakeholders perceived a general increase in ecosystem services over the last 50 years, mainly through cultural services such as recreation, tourism, and relaxation & life quality (Fig. 5). They also perceived a decrease in water-dependent services such as water quality regulation, energy generation (hydropower), leisure (swimming in the river), traditional ecological knowledge, raw material collection, food provision (fish and crabs), and local varieties (genetic resources) from upstream to downstream. The change in ecosystem services was perceived across stakeholder groups, indicating that changes affected all social groups considered. Additionally, interviewees pointed out valuable aspects of the ecosystem that are not usually included as ecosystem services: biodiversity, nature tourism (which provides job opportunities), traditional ecological knowledge, and health (such as disease prevention).

Fig. 5.

Identifying ecosystem services and flows in our case study. The Y-axis represents the ecosystem services mentioned by stakeholders. The X-axis represents the number of comments referring to each ecosystem service currently delivered in the study area (yellow bars) and 50 years ago (blue bars)

Ranking ecosystem services: Water supply, water quality regulation, and water flow regulation were the ecosystem services that were ranked the highest, whereas energy supply, raw material production, and medicinal plants were ranked the lowest. Responses within each stakeholder group varied, which prevented us from defining stakeholder groups according to their preferences for ecosystem services.

Discussion

In this paper, we go a step further in the social evaluation of ecosystem services by identifying three basic aspects that should be explicit in such assessments: (1) the spatial and temporal context (boundary delimitation); (2) the social context (who evaluates); and (3) the methodology used (how ecosystem services are evaluated). We aim to launch social valuations of ecosystem services not only as an isolated exercise in valuation, or restricted to merely valuate cultural ecosystem services, but to advance our knowledge on the value that society gives to ecosystems, to enable comparisons across studies, and to improve land management plans.

Although we tested the framework in a single case study (Felipe-Lucia 2012), our experience in socio-ecological research (Comín et al. 2005; Escalera Reyes 2011), the insights gained from the literature review, and the fact that the outlines proposed are broad, enable us to propose this framework as a useful approach to guide the social assessment of ecosystem services in a wide context. Therefore, we encourage both researchers and practitioners to use this framework in other case studies to test its validity and to enhance it if any pitfalls are found.

The review showed the potential of the social approach for ecosystems management, and also revealed some gaps in meeting such a challenge. At the stage of the spatial–temporal context, there are currently a low number of ecosystem services evaluations that gathered information across several spatial and temporal scales. However, considering such information would allow the flows of ecosystem services to be estimated. Combining both spatial and temporal flows can be useful to forecast future trends on the extent and direction of ecosystem services derived from land-use and land-cover changes over time (MEA 2005). Iteratively assessing social perceptions would predict support or tensions in society derived from the management actions accomplishing such changes (see Fig. 1).

Additionally, our review disclosed that the use of the social approach in the valuation of ecosystem services operated with the same type of ecosystems as studies from other approaches (Feld et al. 2009; Martin et al. 2012), and that there were some ecosystems not addressed at all. For instance, there is not much knowledge concerning the ecosystem services perception of the inhabitants of polar and desert ecosystems. This indicates that our understanding of the social value of ecosystem services across cultures can be expanded. Accounting with such information could expand our current perception of valuable ecosystem services and enhance management projects in remote areas.

Consistent with the results on the spatial context (the main spatial scales addressed were the supra-local and the municipality), the results of the social context showed that local residents were the group most frequently considered in the studies reviewed, but they were still in the minority among the studies. Listening to the local stakeholders and including their views and concerns might help the projects succeed. Even in larger projects, where decisions are made at the national or regional levels, implementing the views of representatives of local stakeholders whose well-being is affected is recommended (Hicks et al. 2009; Moreno et al. 2014). Neglecting local perceptions can hamper success in management projects that aim to enhance ecosystem services not supported locally (Hauck et al. 2013). Furthermore, on the other hand, projects or demands that arise at the local level are more likely to be implemented if they involve managers at the decision-making level, which are usually larger than local ones.

Regarding the suitability of the different methods exposed, we agree with Tallis et al. (2012) and Ringold et al. (2013) who suggest that an open combination of the two scopes identified would provide the most information, firstly identifying the valuable ecosystem services to stakeholders, and secondly, ranking their preferences (i.e., the value). This is especially important in land management, where trade-offs between alternative land uses are frequent, and a selection of ecosystem services to be enhanced or decreased might be required (Hicks et al. 2013).

In addition, we stress the need to clearly distinguish the social valuation from the economic valuation based on social preferences as separate approaches for the assessment of the ecosystem services. Our review showed that 264 papers outlined as “social valuations” were actually based on preferences revealed through methods using only monetary terms. Forty-five percent of our total records considered an economic valuation of some sort, 24 % were based on revealed preferences (including contingent valuation and “willingness-to-pay/accept/give-time” surveys), 17 % used choice experiments or modeling, 11 % stated preferences, and 2 % used cost-benefit analysis. Given that we did not search for the term “economics” in our review, these figures might not be definitive. We provide them merely to draw attention to the fact that a large number of papers included in “social valuation” of ecosystem services are actually economic valuations based exclusively on social preferences. As we do not aim to expand on the differences between both approaches or the risks of limiting research on social preferences to monetary terms, we refer to other authors for further discussion (Funtowicz and Ravetz 1994; Chee 2004; Wegner and Pascual 2011; Farley 2012; Casado-Arzuaga et al. 2013). Defining clear methods for the social valuation of ecosystem services would strengthen the social approach as the alternative to economics to assess ecosystem services by society.

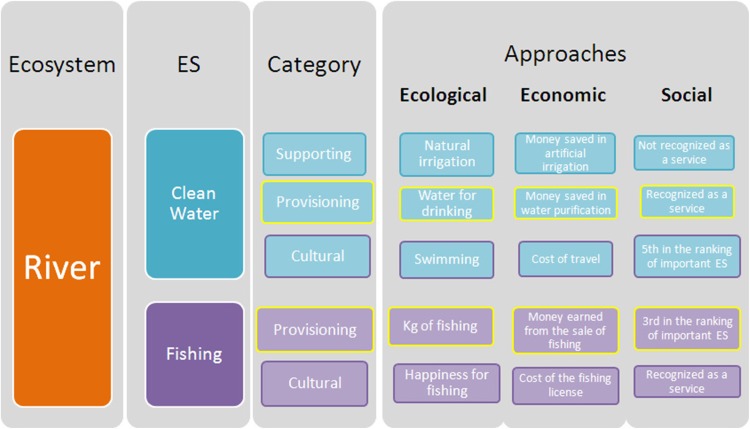

Finally, although in this paper we have developed one of the three approaches for the evaluation of ecosystem services, we understand that the three approaches together are required to properly assess the value of ecosystem services (Daily 1997) and to inform decision-making. In the example provided in Fig. 6, each ecosystem service (for example, clean water and fishing) is ascribed to more than one category—among them, regulating, supporting, provisioning, or cultural—as proposed by some authors (e.g., Chan et al. 2012a), and is evaluated using different indicators according to the approach adopted. Currently, most assessments intend to capture the whole value of ecosystem services by focusing solely on the ecological and economic approaches (Satz et al. 2013), while ignoring the social one (e.g., Kremen and Ostfeld 2005; Spangenberg and Settele 2010; but see Oteros-Rozas et al. 2012; Martín-López et al. 2014). Researchers probably assume that valuable ecosystem services are obvious and that they are able to identify them without including the opinion of society (Chan et al. 2012a), and even question whether using all three approaches might provide redundant measures (Brown 2013). However, it has been argued that using an integrated approach is the best way to make informed decisions based on ecological sustainability, economic efficiency, and social justice (Costanza 2000; MEA 2005; Farley 2012).

Fig. 6.

Example of approaches that can be applied to evaluate two ecosystem services (ES) provided by riverine ecosystems. Although each service is often ascribed to a unique category (second column, blue box for supporting and purple box for cultural), it can actually be evaluated by more than one category (third column, blue frame for supporting, yellow frame for provisioning, and purple frame for cultural). Furthermore, each category can be evaluated from the ecological, economic, or social approach, using different indicators. The assessment of all three approaches is strongly recommended for a complete valuation of ecosystem services

Practical recommendations

We encourage scientists and practitioners to: (1) understand ecosystem services flows by comparing ecosystem services preferences across time and space, for which interviewers must clearly specify the temporal and spatial framework; (2) include a variety of stakeholders from all social ranges, grouping them according to their social characteristics and their use of the ecosystem; and (3) evaluate ecosystem services via both identification and ranking, insisting that stakeholders propose ecosystem services that are valuable to them, without listing constraints. For this third recommendation, ecosystem services need to be clearly defined, by indicating or separately evaluating the different benefits each ecosystem service can provide (Reyers et al. 2013). Also, the role of stakeholder representatives should be stated to ensure that they express the preferences of the organization they represent; such organizations should establish their own ranking of ecosystem services preferences.

Thus, we need to distinguish (i) the cultural services from the social approach and (ii) the social approach from the economic valuation based on social preferences. Additionally, we suggest taking the proposed framework into an iterative process, which deepens and evolves as do changes in the social–ecological context, human needs, and land uses.

Finally, the baseline question of whether we are actually able to establish our preferences for ecosystem services remains unsolved. In our western-culture society, we are so rarely asked to appreciate what we obtain for free and to put into practice our system of values that it is difficult for us to establish preferences for ecosystem services or even to identify the ecosystem services we receive. We believe that the underlying challenge of our society is to enable citizens to express their opinions for decision-making. Fair social participation in decision-making based on ecosystem services assessments leads to our well-being.

Conclusion

To complement the ecological and economic assessments of ecosystem services, a three-step framework for the social valuation of ecosystem services is proposed. This framework provides a useful tool to contrast outcomes across studies and to support land planning and management. We address important questions at each stage, such as considering spatial–temporal flows, including stakeholders from all social ranges, and using two complementary methods (both identification and ranking) to value ecosystem services. Additionally, we stress the need to differentiate (i) the cultural services from the social approach and (ii) the social approach from the economic valuation based on social preferences. Defining clear methods for the social valuation of ecosystem services would strengthen this approach as the alternative to economics to assess ecosystem services by society. We aim to launch the social valuation of ecosystem services as a tool to enable citizens to express their opinions regarding decision-making. A fair social participation in decision-making based on ecosystem services assessments is the way to human well-being.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge all participants in the interviews as well as others who provided meaningful information to understand the socio-ecological system of the River Piedra basin. We thank M. Gartzia, A. de Frutos, and an anonymous reviewer for valuable comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. MFL was awarded a grant by the CSIC (Spanish National Research Council) under the JAE‐predoc program (JAE-Pre-2010-044), co-financed by the European Social Fund.

Biographies

María R. Felipe-Lucia

is a PhD candidate at the Pyrenean Institute of Ecology (Instituto Pirenaico de Ecología-CSIC) in Jaca, Spain, and at the Universidad Pablo de Olavide in Sevilla, Spain. Her research interests include ecological restoration, the valuation of ecosystem services, and the public participation in land planning and management. She is specialized in riparian ecosystems including agroecosystems and works from the local to the landscape scale.

Francisco A. Comín

is Research Professor at Instituto Pirenaico de Ecologia-CSIC. His research interests range from basic biogeochemical processes of aquatic ecosystems to applied aspects of ecological restoration, including integrating social aspects, particularly on wetlands and watersheds.

Javier Escalera-Reyes

is Professor of Social Anthropology at the University Pablo de Olavide of Seville, where he is director of the Social Research Group and Participatory Action (GISAP), and co-director of the Master’s Degree in Social Research Applied to the Environment, and of the Doctoral Program in Environmental Studies. His research interests include political anthropology, sociability, associations, environment and natural areas, tourism, participatory research, cultural heritage, and collective identities.

Footnotes

Note that in this case, regional refers to representatives from a county or province.

Note that in this case, regional refers to representatives from a county or province.

Contributor Information

María R. Felipe-Lucia, Phone: (+34) 976369393, Email: maria.felipe.lucia@gmail.com

Francisco A. Comín, Phone: (+34) 976369393, Email: comin@ipe.csic.es

Javier Escalera-Reyes, Phone: (+34) 954348968, Email: fjescrey@upo.es.

References

- Alcamo J, Ash NJ, Butler CD, Callicott JB, Capistrano D, Carpenter S, Castilla JC, Chambers R, et al. Ecosystems and human well-being: A framework for assessment. Washington, DC: Island Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, A., J. Atwood, P. August, C. Byron, S. Cobb, C. Foster, C. Fry, A. Gold, et al. 2009. Coastal lagoons and climate change: Ecological and social ramifications in the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf coast ecosystems. Ecology and Society.

- Antunes P, Kallis G, Videira N, Santos R. Participation and evaluation for sustainable river basin governance. Ecological Economics. 2009;68:931–939. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2008.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aretano R, Petrosillo I, Zaccarelli N, Semeraro T, Zurlini G. People perception of landscape change effects on ecosystem services in small Mediterranean islands: A combination of subjective and objective assessments. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2013;112:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belton, V., and T. Stewart. 2001. Multiple criteria decision analysis - an integrated approach. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kuwler Academic Publishers.

- Berkes F, Turner NJ. Knowledge, learning and the evolution of conservation practice for social–ecological system resilience. Human Ecology. 2006;34:479–494. doi: 10.1007/s10745-006-9008-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G. 2013. The relationship between social values for ecosystem services and global land cover: An empirical analysis. Ecosystem Services 5: 58–68. doi:10.1016/j.ecoser.2013.06.004.

- Casado-Arzuaga I, Madariaga I, Onaindia M. Perception, demand and user contribution to ecosystem services in the Bilbao Metropolitan Greenbelt. Journal of Environmental Management. 2013;129:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.05.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo A, Magaña A, Pujadas A, Martínez L, Godínez C. Understanding the interaction of rural people with ecosystems: A case study in a tropical dry forest of Mexico. Ecosystems. 2005;8:630–643. doi: 10.1007/s10021-005-0127-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KMA, Satterfield T, Goldstein J. Rethinking ecosystem services to better address and navigate cultural values. Ecological Economics. 2012;74:8–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.11.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KMA, Guerry AD, Balvanera P, Klain S, Satterfield T, Basurto X, Bostrom A, Chuenpagdee R, et al. Where are cultural and social in ecosystem services? A framework for constructive engagement. BioScience. 2012;62:744–756. doi: 10.1525/bio.2012.62.8.7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chee YE. An ecological perspective on the valuation of ecosystem services. Biological Conservation. 2004;120:549–565. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2004.03.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Comín FA, Menéndez M, Pedrocchi C, Moreno S, Sorando R, Cabezas A, García M, Rosas V, et al. Wetland restoration: Integrating scientific–technical, economic, and social perspectives. Ecological Restoration. 2005;23:182–186. doi: 10.3368/er.23.3.182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R. 2000. Social goals and the valuation of ecosystem services. Ecosystems 3: 4–10. doi:10.1007/s100210000002.

- Cowling RM, Egoh B, Knight AT, O’Farrell PJ, Reyers B, Rouget’ll M, Roux DJ, Welz A, et al. An operational model for mainstreaming ecosystem services for implementation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:9483–9488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706559105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daily, G.C. 1997. Nature’s services: Societal dependence on natural ecosystems. Washington, DC: Island Press.

- Daniel TC, Muhar A, Arnberger A, Aznar O, Boyd JW, Chan KMA, Costanza R, Elmqvist T, et al. Contributions of cultural services to the ecosystem services agenda. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:8812–8819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114773109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escalera Reyes J. Public participation and socioecological resilience. In: Egan D, Hjerpe EE, Abrams J, editors. Human dimensions of ecological restoration. Society for Ecological Restoration: Island Press/Center for Resource Economics; 2011. pp. 79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Farley J. Ecosystem services: The economics debate. Ecosystem Services. 2012;1:40–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2012.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feld CK, Martins da Silva P, Paulo Sousa J, De Bello F, Bugter R, Grandin U, Hering D, Lavorel S, et al. Indicators of biodiversity and ecosystem services: A synthesis across ecosystems and spatial scales. Oikos. 2009;118:1862–1871. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2009.17860.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Felipe-Lucia MR. Social dimension of ecosystem services: The case of river Piedra’s valley. Sevilla: Universidad Pablo de Olavide; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Folke C, Carpenter S, Elmqvist T, Gunderson L, Holling CS, Walker B. Resilience and sustainable development: Building adaptive capacity in a world of transformations. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment. 2002;31:437–440. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447-31.5.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman RE. Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Boston: Pitman Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Funtowicz SO, Ravetz JR. The worth of a songbird: Ecological economics as a post-normal science. Ecological Economics. 1994;10:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0921-8009(94)90108-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Llorente M, Martin-Lopez B, Iniesta-Arandia I, Lopez-Santiago CA, Aguilera PA, Montes C. The role of multi-functionality in social preferences toward semi-arid rural landscapes: An ecosystem service approach. Environmental Science & Policy. 2012;19–20:136–146. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2012.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot RS, Wilson MA, Boumans RMJ. A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecological Economics. 2002;41:393–408. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(02)00089-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hauck J, Goerg C, Varjopuro R, Ratamaki O, Jax K. Benefits and limitations of the ecosystem services concept in environmental policy and decision making: Some stakeholder perspectives. Environmental Science & Policy. 2013;25:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2012.08.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hein L, van Koppen K, de Groot RS, van Ierland EC. Spatial scales, stakeholders and the valuation of ecosystem services. Ecological Economics. 2006;57:209–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks CC, McClanahan TR, Cinner JE, Hills JM. Trade-offs in values assigned to ecological goods and services associated with different coral reef management strategies. Ecology and Society. 2009;14:10. [Google Scholar]

- Hicks CC, Graham NAJ, Cinner JE. Synergies and tradeoffs in how managers, scientists, and fishers value coral reef ecosystem services. Global Environmental Change. 2013;23:1444–1453. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.07.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kremen C, Ostfeld RS. A call to ecologists: Measuring, analyzing, and managing ecosystem services. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2005;3:540–548. doi: 10.1890/1540-9295(2005)003[0540:ACTEMA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamarque P, Tappeiner U, Turner C, Steinbacher M, Bardgett RD, Szukics U, Schermer M, Lavorel S. Stakeholder perceptions of grassland ecosystem services in relation to knowledge on soil fertility and biodiversity. Regional Environmental Change. 2011;11:791–804. doi: 10.1007/s10113-011-0214-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Likert, R. 1932. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology 140: 1–55.

- Maass JM, Balvanera P, Castillo A, Daily GC, Mooney HA, Ehrlich P, Quesada M, Miranda A, et al. Ecosystem services of tropical dry forests: Insights from long-term ecological and social research on the Pacific Coast of Mexico. Ecology and Society. 2005;10:17. [Google Scholar]

- Martin LJ, Blossey B, Ellis E. Mapping where ecologists work: biases in the global distribution of terrestrial ecological observations. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2012;10:195–201. doi: 10.1890/110154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-López B, Gómez-Baggethun E, García-Llorente M, Montes C. Trade-offs across value-domains in ecosystem services assessment. Ecological Indicators. 2014;37:220–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2013.03.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-López B, Iniesta-Arandia I, García-Llorente M, Palomo I, Casado-Arzuaga I, García Del Amo D, Gómez-Baggethun E, Oteros-Rozas E, et al. Uncovering ecosystem service bundles through social preferences. PLoS One. 2012;7:e3897. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzel S, Teng J. Ecosystem services as a stakeholder-driven concept for conservation science. Conservation Biology. 2010;24:907–909. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) Ecosystems and human well-being: Our human planet: Summary for decision makers. Washington, DC: Island Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, J., I. Palomo, J. Escalera, B. Martín-López, and C. Montes. 2014. Incorporating ecosystem services into ecosystem-based management to deal with complexity: A participative mental model approach. Landscape Ecology: 1–15. doi:10.1007/s10980-014-0053-8.

- Newton AC, Hodder K, Cantarello E, Perrella L, Birch JC, Robins J, Douglas S, Moody C, et al. Cost-benefit analysis of ecological networks assessed through spatial analysis of ecosystem services. Journal of Applied Ecology. 2012;49:571–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2664.2012.02140.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oteros-Rozas E, Gonzalez JA, Martin-Lopez B, Lopez CA, Zorrilla-Miras P, Montes C. Evaluating ecosystem services in transhumance cultural landscapes an interdisciplinary and participatory framework. Gaia-Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society. 2012;21:185–193. [Google Scholar]

- Plieninger T, Dijks S, Oteros-Rozas E, Bieling C. Assessing, mapping, and quantifying cultural ecosystem services at community level. Land Use Policy. 2013;33:118–129. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond CM, Singh GG, Benessaiah K, Bernhardt JR, Levine J, Nelson H, Turner NJ, Norton B, et al. Ecosystem services and beyond: Using multiple metaphors to understand human–environment relationships. BioScience. 2013;63:536–546. doi: 10.1525/bio.2013.63.7.7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reyers, B., R. Biggs, G.S. Cumming, T. Elmqvist, A.P. Hejnowicz, and S. Polasky. 2013. Getting the measure of ecosystem services: a social–ecological approach. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 11: 268–273. doi:10.1890/120144.

- Ringold PL, Boyd J, Landers D, Weber M. What data should we collect? A framework for identifying indicators of ecosystem contributions to human well-being. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2013;11:98–105. doi: 10.1890/110156. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, T.L. 1980. The analytic hierarchy process: Planning, priority setting, resource allocation. McGraw-Hill.

- Satz D, Gould RK, Chan KMA, Guerry A, Norton B, Satterfield T, Halpern BS, Levine J, et al. The challenges of incorporating cultural ecosystem services into environmental assessment. AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment. 2013;42:675–684. doi: 10.1007/s13280-013-0386-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg JH, Settele J. Precisely incorrect? Monetising the value of ecosystem services. Ecological Complexity. 2010;7:327–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ecocom.2010.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tallis H, Lester SE, Ruckelshaus M, Plummer M, McLeod K, Guerry A, Andelman S, Caldwell MR, et al. New metrics for managing and sustaining the ocean’s bounty. Marine Policy. 2012;36:303–306. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2011.03.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trabucchi M, Comín FA, O’Farrell PJ. Hierarchical priority setting for restoration in a watershed in NE Spain, based on assessments of soil erosion and ecosystem services. Regional Environmental Change. 2013;13:911–926. doi: 10.1007/s10113-012-0392-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RK, Paavola J, Cooper P, Farber S, Jessamy V, Georgiou S. Valuing nature: Lessons learned and future research directions. Ecological Economics. 2003;46:493–510. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(03)00189-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valles M. Técnicas cualitativas de investigación social. Reflexión metodológica y práctica profesional. Madrid: Ed. Síntesis; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen S, Koziell I. Integrating global and local values: A review of biodiversity assessment. London: IIED; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wegner G, Pascual U. Cost-benefit analysis in the context of ecosystem services for human well-being: A multidisciplinary critique. Global Environmental Change-Human and Policy Dimensions. 2011;21:492–504. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson MA, Carpenter SR. Economic valuation of freshwater ecosystem services in the United States: 1971–1997. Ecological Applications. 1999;9:772–783. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.