Abstract

Metazoan genomes encode exposure memory systems to enhance survival and reproductive potential by providing mechanisms for an individual to adjust during lifespan to environmental resources and challenges. These systems are inherently redox networks, arising during evolution of complex systems with O2 as a major determinant of bioenergetics, metabolic and structural organization, defense, and reproduction. The network structure decreases flexibility from conception onward due to differentiation and cumulative responses to environment (exposome). The redox theory of aging is that aging is a decline in plasticity of genome–exposome interaction that occurs as a consequence of execution of differentiation and exposure memory systems. This includes compromised mitochondrial and bioenergetic flexibility, impaired food utilization and metabolic homeostasis, decreased barrier and defense capabilities and loss of reproductive fidelity and fecundity. This theory accounts for hallmarks of aging, including failure to maintain oxidative or xenobiotic defenses, mitochondrial integrity, proteostasis, barrier structures, DNA repair, telomeres, immune function, metabolic regulation and regenerative capacity.

Keywords: Redox systems biology, Oxidative stress, Redox signaling

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

A redox interface connects an organism and its environment.

-

•

Genetically encoded exposure memory systems evolved along with multicellularity in an O2-rich environment.

-

•

Exposure memory allows an individual to adapt to resources and threats during lifespan.

-

•

Aging is an irreversible decline in adaptability due to execution of exposure memory systems.

Introduction

Hundreds of philosophers and scientists have addressed the topics of longevity and aging, and many theories have been advanced. These have been recently reviewed [1], and I make no attempt to further summarize these important contributions. Rather, the present article provides a conceptual review based upon the emerging concept that redox systems function as a critical interface between the genome and the exposome [2,3]. Relying extensively upon emerging understanding of redox systems biology, acquired epigenetic memory systems, and deductive reasoning, a simple theory is derived that aging is the decline of the adaptive interface of the functional genome and exposome that occurs due to cell and tissue differentiation and cumulative exposures and responses of an organism. This theory is not limited to redox processes but has a redox-dependent character due to the over-riding importance of electron transfer in energy supply, defense, reproduction and molecular dynamics of protein and cell signaling.

Several years ago, I presented a redox hypothesis of oxidative stress [4] in which I concluded that oxidative stress is predominantly a process involving 2-electron, non-radical reactions rather than commonly considered 1-electron, free radical reactions. The central arguments were that (1) experimental measures showed that non-radical flux substantially exceeds free radical flux under most oxidative stress conditions, (2) radical scavenger trials in humans failed to show health benefits, and (3) normal cell functions involving sulfur switches are readily disrupted by non-radical oxidants. The redox hypothesis is thus founded upon the concept that oxidative stress includes disruption of redox circuitry [5,6] in addition to the macromolecular damage resulting from an imbalance of prooxidants and antioxidants [7].

The redox hypothesis of oxidative stress contained four postulates:

-

1.

All biologic systems contain redox elements [e.g., redox-sensitive cysteines], which function in cell signaling, macromolecular trafficking and physiologic regulation.

-

2.

Organization and coordination of the redox activity of these elements occurs through redox circuits dependent upon common control nodes (e.g., thioredoxin, GSH).

-

3.

The redox-sensitive elements are spatially and kinetically insulated so that “gated” redox circuits can be activated by translocation/aggregation and/or catalytic mechanisms.

-

4.

Oxidative stress is a disruption of the function of these redox circuits caused by specific reaction with the redox-sensitive thiol elements, altered pathways of electron transfer, or interruption of the gating mechanisms controlling the flux through these pathways.

The current article represents an extension and development of these concepts into a redox theory of aging. This redox theory is not exclusively limited to redox reactions but rather emphasizes the key role of electron transfer in supporting central energy currencies (ATP, phosphorylation, acetylation, acylation, methylation and ionic gradients across membranes) and providing the free energy to support metabolism, cell structure, biologic defense mechanisms and reproduction. Importantly, improved understanding of the integrated nature of redox control and signaling in complex, multicellular organisms [8] provide a foundation for this generalized theory.

Improved understanding of redox circuitry

The logic of development of the redox theory of aging depends upon recognition that the third postulate of the redox hypothesis [4] probably applies to a relatively limited subset of redox switches that function in redox signaling [8]. Insulated pathways with gating mechanisms, as discussed in consideration of redox systems biology [9], may be relatively rare. Instead, a much larger number of redox switches exist that support redox sensing to coordinate and integrate functional networks [8,10,11]. These redox sensors exist in dynamic steady state, with Cys in multiple proteins in functional networks sharing similar redox character [10]. They have promiscuous reactivities, with multiple targets and switchable specificities. For example, most protein thiols are oxidizable by hydrogen peroxide and some are reduced by either thioredoxin or glutathione systems [12]. Furthermore, inhibition of thioredoxin reductase activity does not invariably result in thioredoxin oxidation [13], implying alternate reductant system for thioredoxin. Additionally, electron flow from thioredoxin reductase switches between targets due to the relative abundances of the targets [14]. Many thioredoxin-like proteins exist [15], but their reactivities and specificities are largely uncharacterized. These and many other observations show that protein redox systems are not highly insulated but rather part of a redox network with many possible electron pathways determined by relative abundance and reactivity of the elements.

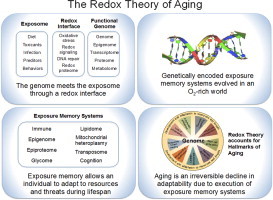

Available evidence indicates that these redox systems are organized within interacting metabolomics and proteomics networks (Fig. 1). Little effort has been made to organize the large number of characterized redox enzyme reactions into a metabolomics network structure, but the redox proteomic structure has been outlined as a bilateral hierarchical structure dependent upon reductant hubs and oxidant hubs [16]. Scale-free hierarchical structures are inherently stable [17,18], and readily accommodate redox control of 214,000 Cys encoded in the human genome [16]. Thus, an overall biological redox system can be viewed as (1) a series of electron donors maintaining the NAD and NADP redox couples, (2) the terminal electron acceptor, O2, maintaining H2O2 and other oxidants, and (3) intermediary redox modules maintaining redox organizational structure of cell functions. In analogy to the hierarchy of gene regulation, this hierarchy provides a framework to map the redox circuitry of cells [16]. Important recent advances include clarification of oxidative redox regulons, now including peroxiredoxins [19,20], glutathione S-transferases [21,22] for thiols and a range of methionine redox functions [23]. This redox system interacts with other post-translational modifications such as nitrosylation, persulfidation and acylation, to provide a multidimensional epiproteome control structure [2].

Fig 1.

Redox biology of metazoans. Metazoans depend upon redox processes to support energetics, metabolic and structural organization, separation from and defense against external environment, and reproduction. The overall redox structure is a complex network including small molecules, measured by redox metabolomics, and proteins, measured by redox proteomics. Metal ions derived from the environment are a major variable not explicitly shown, but impact both the redox metabolome and redox proteome by interfering with essential metal ion functions and catalyzing non-enzymatic reactions. The enzymology of redox reactions has been studied in detail and organized by the Enzyme Commission in terms of electron donors and electron acceptors in enzyme-catalyzed reactions (see http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/iubmb/enzyme/EC1/). No systematic consideration of the redox metabolome is currently available. The elements of the redox proteome are mostly known, but systematic knowledge of spatial and temporal distributions is not available. Redox systems biology provides an initial framework for development, but quantitative data for abundance and kinetics are limited. Ultimately, this knowledge is needed to understand and develop strategies to improve healthy longevity.

The redox proteome is an adaptive interface of the genome and exposome

Logical argument 1

Redox modifications of the proteome provide a system to sense, avoid and defend against environmental oxidants and other toxic chemicals.

Observations concerning the redox proteome considerably impact concepts of aging when considered within the context of the exposome. The exposome was defined by Wild [24] as a conceptual grid of cumulative lifelong exposures to complement the genome in understanding human disease [24,25]. The concept includes infections, behavioral exposures, diet, nutrition and microbiome [26], and has been further developed for environmental health sciences [27,28], including epigenetic changes and mutations [29].

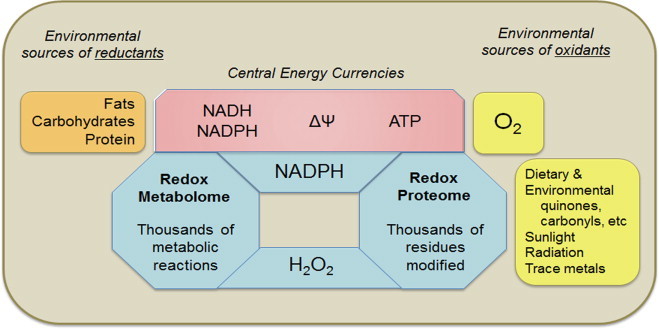

The redox proteome sits as a first defense against xenobiotic stresses and thus represents an adaptive interface of the genome and exposome [3] (Fig. 2). Relatively stable protein modifications, such as those from reactive lipid modifications of protein, extend the reversible oxidations of Cys or Met to provide sustained stress signals [30,31]. An understanding of this exposure memory helps clarify the role of redox systems in evolution of complex structures. Multiple exposure memory systems support organismic development and adaptation to diet and environment. Reversible oxidation of metabolites and amino acids in proteins are most responsive, but slow and non-reversible proteomic changes also provide exposure memory. Even longer lasting epigenetic changes, linked to the redox systems by transmethylation of methionine, can sustain exposure memory over a lifespan, and higher cognitive function similarly serves as a long-term interface between genome and environment. Importantly, this series of exposure memory systems provides a way to think about the incessant progression from conception to death and the meaning of aging and longevity.

Fig 2.

The redox metabolome and redox proteome serve as an adaptive interface for genome–exposome interaction. The exposome includes essential nutrients, other chemicals from food, products of the microbiome, food supplements and drugs, commercial products and environmental chemicals. Based upon Jones et al. 2012, Go and Jones 2013 and Go and Jones 2014. “Industrial-pollution” by John Tarantino, Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Industrial-pollution.JPG#mediaviewer/File:Industrial-pollution.JPG.

Increased atmospheric O2 diversified habitats

Logical argument 2

Increased atmospheric O2 supported redox-driven speciation and evolution of complexity in metazoans

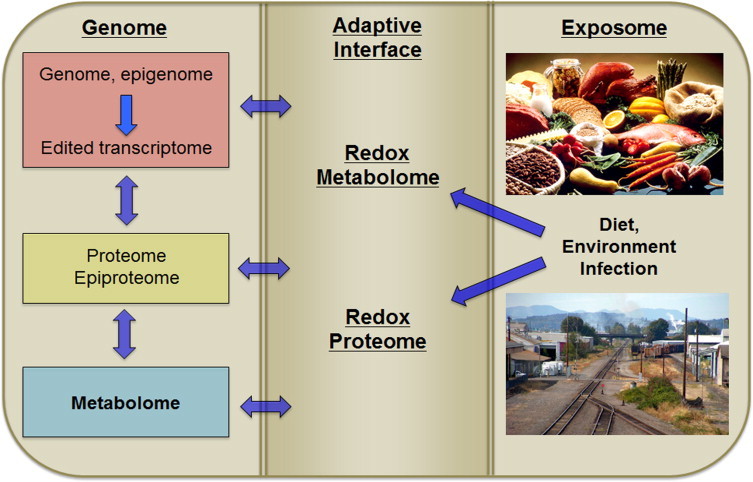

Atmospheric O2 increased substantially about 900 million years ago. By this time, archebacteria, eubacteria and single cell eukaryotes had evolved biologic solutions to the challenges of life, i.e., mechanisms to acquire and maintain bioenergetics, sustain organized metabolism and structure, defend against environmental threats and reproduce. These systems included Cys and Met in the proteome, functioning under relatively low (<1%) O2 atmosphere. Increase to 21% O2 resulted in increased production of H2O2 by reaction of O2 with thiols and other redox elements in living systems. This provided driving force for mechanisms to avoid exposure to O2 and to eliminate H2O2. At the same time, more efficient ATP production by mitochondria provided driving force to seek and maintain O2 exposure. Thus, the O2 atmosphere created forces for speciation to avoid O2, to tolerate O2 and to maximize O2 supply. The reversible oxidation of Cys and Met residues within proteins were harnessed to sense and support these adaptations.

Viewed as an adaptive interface of the genome and proteome, the redox proteome therefore provides an underlying logic to current functions of redox switches in differentiation and development. Miseta and Csutora [32] showed that the cysteine proteome co-evolved with the evolution of complexity. Despite selection against cysteine in the proteome, cysteine content increased with phylogenetic complexity from 0.5% in prokaryotes to >2% in mammals. The methionine proteome and other reactive centers, like those of the NADPH oxidases, thioredoxins, peroxiredoxins and selenoenzymes, similarly coevolved. Evolution of adaptive redox mechanisms yielded selective advantage for complex organisms to tolerate diverse and unique environments.

A conceptual framework for this co-evolution is provided in Fig. 3. Already at the time of evolution of O2 in the atmosphere, unicellular organisms had mechanisms to manage energetics, maintain molecular order (metabolic and structural organization), defend again predation and hostile environmental factors, and reproduce. Increased atmospheric O2 created different habitats and opportunity for organisms with oxidant sensing and detoxification, oxidative DNA damage repair systems and more efficient mitochondrial energy production.

Fig 3.

Co-evolution of thiol systems with biological complexity. Life is thought to have evolved under relatively reducing conditions, with a substantial increase in atmospheric O2 only after efficient photosynthetic organisms were present. Miseta and Czutora (2000) showed that the percentage of Cys encoded in genomes increased from about 0.5% to >2% in association with evolution of complexity. Redox-sensitive Cys are common in the proteome, are redox sensitive and are extensively conserved with evolution, consistent with roles in redox sensing, redox processing and redox signaling. Viewed as a redox interface between the genome and exposome, the O2 environment provided a driving force for evolution while the redox sensing, processing and signaling capabilities enabled speciation with diverse mechanisms to improve energy utilization, metabolic organization, defenses against environmental threats and reproduction.

Redox mechanisms were harnessed for multicellular differentiation to enhance adaptability

Logical argument 3

Evolution of multicellularity utilized available redox mechanisms to support spatiotemporal signaling and molecular memory systems.

Love et al. [33] showed a spatial and temporal sequence of oxidation occurs during wound healing following tadpole tail amputation. Knoefler et al. [34] showed that sequential changes in oxidant generation were directly linked to specific protein Cys oxidation in Caenorhabditis elegans development. These findings provide evidence that redox signaling of adaptation to environment were co-opted for spatiotemporal signaling in multicellular organism differentiation and development.

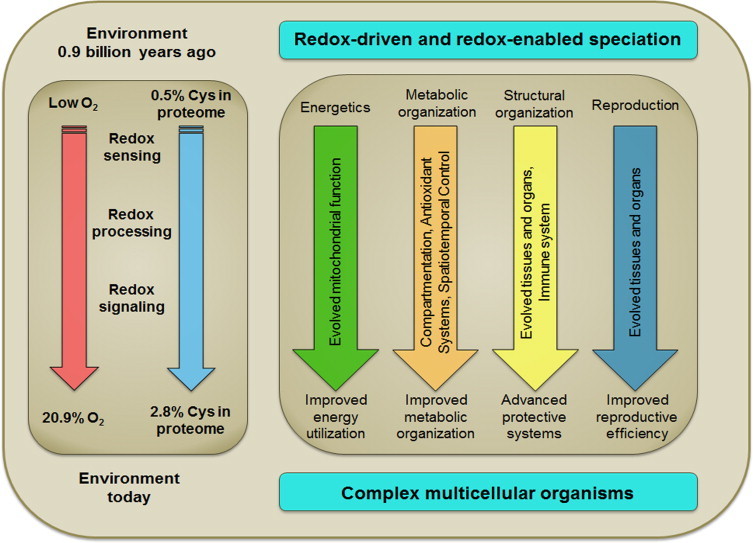

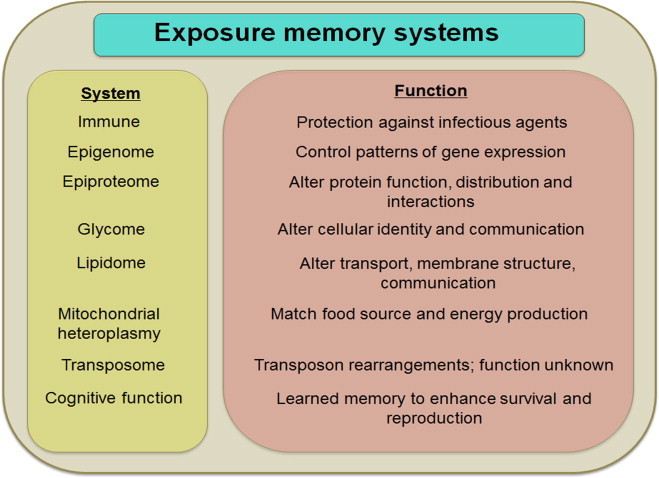

Building upon these concepts, the molecular logic of multicellularity unfolds as a memory system to maintain differentiated phenotypes of cells, which provides the genome a competitive advantage in survival and reproduction by having components with more specialized functions. Differentiated epiproteomic, lipidomic, glycomic and epigenetic systems provide molecular memory (Fig. 4) for genome–exposome interactions. Each is directly or indirectly redox-dependent; all require high-energy metabolites like ATP. The epiproteome is directly modified by oxidation and reaction with oxidized lipid products; epigenetic systems include oxidative demethylases and redox-dependent deacetylases; the systems are linked by the methionine/cysteine metabolism and other components of the redox metabolome. Species gained selective advantage during evolution as memory systems enhanced individual competitiveness for nutrient acquisition, management of O2 supply, defense against predators, and reproduction.

Fig 4.

Molecular memory systems. An interacting series of molecular memory systems enable an individual genome to learn from the exposome, improve health, survival and reproduction of the individual and progeny. Execution of developmental and exposure memory systems decreases flexibility of the molecular systems of the organism.

Decreased genome adaptability with differentiation and exposure memory

Logical argument 4

Molecular memories of differentiation and environmental exposures decrease genomic flexibility to accommodate future environmental challenges.

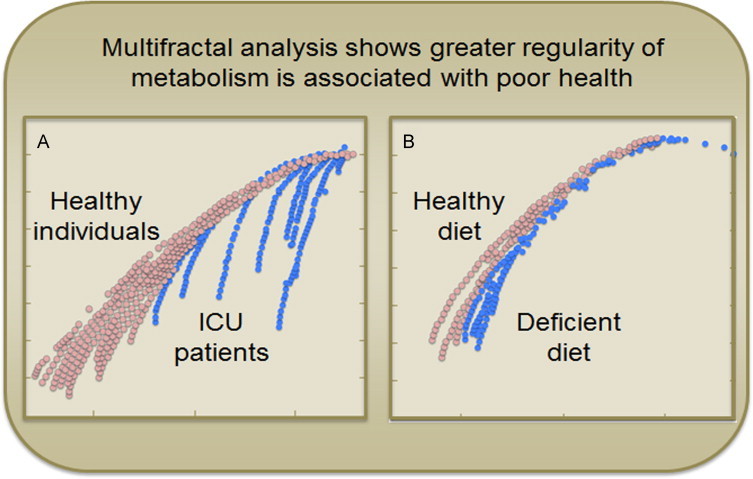

Fractal dynamics [35] have been used to show that irregularity and unpredictability are features of health and that decreased variability and adaptability are associated with disease [36,37]. Ivanov et al. [38,39] used fractal analysis of the human heartbeat to show that a higher Hurst Exponent (H), indicative of greater regularity, was associated with disease, while normal heartbeat exhibited more chaotic behavior and lower H value. Such concepts have been extended to study Parkinson's disease [40], sleep apnea [41], and sudden cardiac death [42]. In our own studies, healthy individuals responding to malnutrition induced by a diet deficient in essential amino acid had increased H in wavelet-transformed plasma metabolomic data [43], indicating decreased metabolic flexibility (Fig. 5). Patients in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) also showed higher H, indicating greater regularity compared to healthy individuals, and those who recovered from the ICU had values return toward those of healthy individuals [43]. Results show that adaptability in biologic systems reflects health and implies that loss of flexibility is critical in aging and longevity.

Fig 5.

Multifractal analysis distinguishes healthy from unhealthy metabolic profiles. A. Plots of the partition function f(a) of wavelet transformed plasma metabolomics analysis shows greater regularity in intensive care unit (ICU) patients (blue) compared to healthy individuals (red). B. Individual receiving diet deficient in the essential amino acid, methionine (−SAA, blue) showed greater regularity than receiving the same diet with adequate methionine (+SAA, Red). Data from Park et al. [43].

Methods are not yet available to evaluate fractal dynamics of the functional genome during lifespan. DNA methylation and epigenetic marks in gametes and fertilized ovum may reflect a basal state for the exposure memory system with high flexibility to adapt to the environment during differentiation, development and maturation. Alternatively, these mechanisms may reflect exposures of parents or earlier generations. In both cases, execution of differentiation and development programs would decrease flexibility within cells and tissues over the lifespan.

Early environmental exposures similarly impact DNA methylation, ribosomal RNA, histone marks, epiproteomic signatures and mitochondrial heteroplasmy. These have a trade-off in improving short-term fitness and reproductive potential with the consequence of long-term decrease in adaptability. Hysteresis introduces variability in the rate and magnitude of effects. Most critically for aging, the differentiation and exposure memory system ultimately limits tolerance to environmental variation and results in failure of energetics, maintenance of molecular order, defenses against xenobiotics and infection and reproductive capability.

The redox theory of aging

Logical argument 5

Aging is a decline in plasticity of genome–exposome interaction that occurs as a consequence of execution of differentiation and exposure memory systems.

From this logical development, one reaches the conclusion that aging is loss of adaptability due to cumulative network responses supporting genome–exposome interaction. The differentiation and adaptive structures allow an individual genome to be molded by exposures throughout life, enhancing fitness for the environment and improving opportunity for success in reproduction. By evolving mechanisms to protect against infectious agents, remember food sources, discriminate good and bad food, avoid dangers, etc., multicellular organisms gained survival advantage.

This exposure memory system, utilizing mechanisms in parallel with developmental programs, also has a cost, and this cost has a central role in aging. Execution of organogenesis programs decreases flexibility of the genome for other programs. Execution of programs in response to exposures decreases flexibility to respond to other exposures. The redox networks controlling cellular energetics, molecular order, organismic defense and reproduction serve to maximize flexibility and adaptability to environment. At the same time, such responses limit future adaptability.

Perhaps more critically for aging and longevity, the networks are interconnected in function. The inter-conversion of redox-derived bioenergetics with metabolic control means that failure of the former is accompanied by compensation and ultimate failure of the latter. The inter-conversion of redox-dependent metabolism and defense mechanisms means that failure of metabolism also results in failure of defense against toxic exposures and infectious organisms. The glutathione redox system becomes oxidized with age; the immune system loses response, the brain accumulates protein aggregates, the lungs and kidneys decline in function, blood vessels lose flexibility and the heart begins to fail. This inter-dependence of energetics, molecular order and defense means that with natural aging, all systems age, even if experimental measures are too insensitive to detect the changes. Death is the eventual collapse of the networks supporting genome–exposome interaction.

Summary and perspective

The logical arguments derived from consideration of accumulating knowledge of the redox proteome and the redox interface of the genome and exposome is that aging is a cumulative failure of the adaptive structures supporting genome–exposome interaction. The integrated redox networks essential for bioenergetics, metabolic and structural organization, defense, and reproduction, ultimately fail due to exhausted differentiation programs and environmental challenge(s) that cannot be accommodated. The exposure memory system allows an individual life history of exposures to determine tolerance to exposures, thereby decreasing or increasing individual lifespan due to respective inappropriate or beneficial exposures.

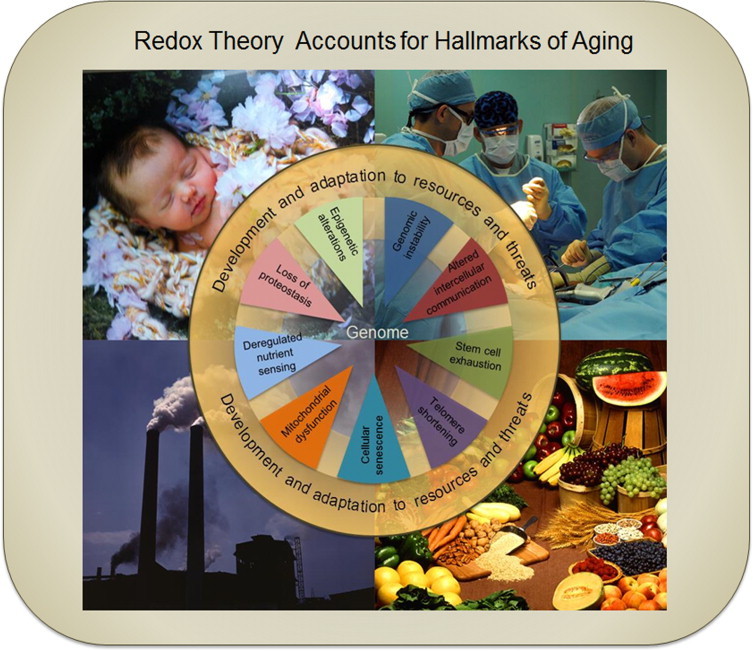

The theory accommodates hallmarks of aging (Fig. 6), such as those involving oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, growth factor signaling and nutrient regulation, failure of proteostasis, telomere shortening, cellular senescence and stem cell exhaustion, epigenetics, barrier failure, intercellular communication, immune system dysfunction, and reproductive exhaustion [1]. Other mechanisms may also be accommodated, such as mitochondrial heteroplasmy to provide a mechanism for cells to change respiratory function during lifespan to adjust to different foods [44]. Similarly, retrotransposable elements, and other poorly understood elements within the genome, could also serve adaptive or maladaptive functions during lifespan [45,46]. On the other hand, some characteristics, such as genomic instability, may represent failure of repair systems and/or failure of the adaptive memory systems.

Fig 6.

Redox theory accounts for hallmarks of aging. The hallmarks of aging as summarized by López-Otín et al. [1], occur as a consequence of the developmental and exposure memory systems encoded in the genome. Execution of the developmental programs and responses to dietary and other environmental exposures alter the DNA methylation and epigenetic marks controlling gene expression. Developmental programs, dietary and environmental exposures determine function of proteostasis systems involving protein synthesis, epiproteomic modifications and degradation. Lifelong responses to dietary excesses and insufficiencies, in the context of early imprinted responses to diet and exposures, deregulate nutrient sensing and utilization. Memory systems for food availability, quality and utilization cause mitochondrial dysfunction. Differentiation programs, cumulative lifelong exposures and execution of response programs lead to cellular senescence. Telomere shortening is a differentiation and exposure memory system for complex organisms. Stem cell exhaustion is a consequence of the evolved differentiation and exposure memory system. Altered intercellular communication is a consequence of execution of differentiation programs and cumulative responses of the adaptive memory system. Genomic instability appears likely to be a failure of the differentiation and exposure memory systems but may also reflect execution of genetic mechanisms or transposon-dependent functions that are not currently understood. Photo credits: Newborn Josey, Holly Jones photography; surgery aboard the USNS Comfort, public domain; fruits and vegetables, Jack Dykinga; smokestacks, Alfred Palmer.

Key challenges exist to formulate appropriate testable hypotheses for function of redox networks due to the complexity of the systems. Evolution resulted in redundant and shared functions. Populations evolve, not individuals. Genetic diversity exists in populations, providing individuals with different adaptability and tolerance to exposures, i.e., a defined exposome is not likely to affect each genome equivalently. Because individuals differ in genome and response to exposome, no experiment is precisely reproducible. Furthermore, no experiment is precisely replicable within an individual because subsequent challenges may not elicit the same response as an initial challenge. None-the-less, clones with controlled sequences of variation in early exposures and later lifetime challenges may prove useful to directly test the theory that aging and longevity are determined by the differentiation and exposure memory systems for genome–exposome interaction.

Acknowledgements

The author gratefully acknowledges critical input from Dr. Young-Mi Go concerning the redox proteome and genome–exposome interactions. Research support provided by NIH Grants AG038746, ES023485, HL113451, ES009047 and ES019776.

References

- 1.López-Otín C., Blasco M.A., Partridge L., Serrano M., Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153(6):1194–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. 23746838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Go Y.M., Jones D.P. The redox proteome. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2013;288(37):26512–26520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R113.464131. 23861437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Go Y.M., Jones D.P. Redox biology: interface of the exposome with the proteome, epigenome and genome. Redox Biology. 2014;2:358–360. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.12.032. 24563853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones D.P. Radical-free biology of oxidative stress. American Journal of Physiology – Cell Physiology. 2008;295(4):C849–C868. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00283.2008. 18684987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones D.P. Redefining oxidative stress. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. 2006;8(9–10):1865–1879. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1865. 16987039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sies H., Jones D.P. Oxidative stress. In: Fink G., editor. Encyclopedia of Stress. second ed. Academic Press; San Diego: 2007. pp. 45–47. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sies H. Oxidative Stress. Academic Press; Orlando: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jones D.P. Redox sensing: orthogonal control in cell cycle and apoptosis signalling. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2010;268(5):432–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02268.x. 20964735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kemp M., Go Y.M., Jones D.P. Nonequilibrium thermodynamics of thiol/disulfide redox systems: a perspective on redox systems biology. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2008;44(6):921–937. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.11.008. 18155672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Go Y.M., Duong D.M., Peng J., Jones D.P. Protein cysteines map to functional networks according to steady-state level of oxidation. Journal of Proteomics and Bioinformatics. 2011;4(10):196–209. doi: 10.4172/jpb.1000190. 22605892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones D.P., Go Y.M. Mapping the cysteine proteome: analysis of redox-sensing thiols. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2011;15(1):103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.12.014. 21216657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Go Y.M., Roede J.R., Walker D.I., Duong D.M., Seyfried N.T., Orr M., Liang Y., Pennell K.D., Jones D.P. Selective targeting of the cysteine proteome by thioredoxin and glutathione redox systems. Molecular and Cellular Proteomics. 2013;12(11):3285–3296. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M113.030437. 23946468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watson W.H., Heilman J.M., Hughes L.L., Spielberger J.C. Thioredoxin reductase-1 knock down does not result in thioredoxin-1 oxidation. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2008;368(3):832–836. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.02.006. 18267104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pader I., Sengupta R., Cebula M., Xu J., Lundberg J.O., Holmgren A., Johansson K., Arnér E.S. Thioredoxin-related protein of 14 kDa is an efficient l-cystine reductase and S-denitrosylase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111(19):6964–6969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317320111. 24778250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woo J.R., Kim S.J., Jeong W., Cho Y.H., Lee S.C., Chung Y.J., Rhee S.G., Ryu S.E. Structural basis of cellular redox regulation by human TRP14. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279(46):48120–48125. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407079200. 15355959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Go Y.M., Jones D.P. Thiol/disulfide redox states in signaling and sensing. Critical Reviews in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology. 2013;48(2):173–181. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2013.764840. 23356510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barabási A.L. Scale-free networks: a decade and beyond. Science. 2009;325(5939):412–413. doi: 10.1126/science.1173299. 19628854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Loscalzo J., Kohane I., Barabasi A.L. Human disease classification in the postgenomic era: a complex systems approach to human pathobiology. Molecular Systems Biology. 2007;3:124. doi: 10.1038/msb4100163. 17625512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Autréaux B., Toledano M.B. ROS as signalling molecules: mechanisms that generate specificity in ROS homeostasis. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2007;8(10):813–824. doi: 10.1038/nrm2256. 17848967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herrmann J.M., Dick T.P. Redox biology on the rise. Biological Chemistry. 2012;393(9):999–1004. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2012-0111. 22944698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiong Y., Manevich Y., Tew K.D., Townsend D.M. S-Glutathionylation of protein disulfide isomerase regulates estrogen receptor alpha stability and function. International Journal of Cell Biology. 2012;2012:273549. doi: 10.1155/2012/273549. 22654912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiong Y., Uys J.D., Tew K.D., Townsend D.M. S-glutathionylation: from molecular mechanisms to health outcomes. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. 2011;15(1):233–270. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3540. 21235352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Labunskyy V.M., Hatfield D.L., Gladyshev V.N. Selenoproteins: molecular pathways and physiological roles. Physiological Reviews. 2014;94(3):739–777. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00039.2013. 24987004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wild C.P. Complementing the genome with an “exposome”: the outstanding challenge of environmental exposure measurement in molecular epidemiology. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers and Prevention. 2005;14(8):1847–1850. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0456. 16103423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wild C.P. The exposome: from concept to utility. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2012;41(1):24–32. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr236. 22296988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones D.P., Park Y., Ziegler T.R. Nutritional metabolomics: progress in addressing complexity in diet and health. Annual Review of Nutrition. 2012;32:183–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-072610-145159. 22540256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rappaport S.M. Implications of the exposome for exposure science. Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology. 2011;21(1):5–9. doi: 10.1038/jes.2010.50. 21081972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rappaport S.M., Smith M.T. Epidemiology. Environment and disease risks. Science. 2010;330(6003):460–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1192603. 20966241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller G.W., Jones D.P. The nature of nurture: refining the definition of the exposome. Toxicological Sciences. 2014;137(1):1–2. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft251. 24213143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higdon A., Diers A.R., Oh J.Y., Landar A., Darley-Usmar V.M. Cell signalling by reactive lipid species: new concepts and molecular mechanisms. Biochemical Journal. 2012;442(3):453–464. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111752. 22364280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Higdon A.N., Landar A., Barnes S., Darley-Usmar V.M. The electrophile responsive proteome: integrating proteomics and lipidomics with cellular function. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. 2012;17(11):1580–1589. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.4523. 22352679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miseta A., Csutora P. Relationship between the occurrence of cysteine in proteins and the complexity of organisms. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2000;17(8):1232–1239. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026406. 10908643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Love N.R., Chen Y., Ishibashi S., Kritsiligkou P., Lea R., Koh Y., Gallop J.L., Dorey K., Amaya E. Amputation-induced reactive oxygen species are required for successful Xenopus tadpole tail regeneration. Nature Cell Biology. 2013;15(2):222–228. doi: 10.1038/ncb2659. 23314862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knoefler D., Thamsen M., Koniczek M., Niemuth N.J., Diederich A.K., Jakob U. Quantitative in vivo redox sensors uncover oxidative stress as an early event in life. Molecular Cell. 2012;47(5):767–776. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.016. 22819323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldberger A.L., West B.J. Fractals in physiology and medicine. Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 1987;60(5):421–435. 3424875 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maxim V., Sendur L., Fadili J., Suckling J., Gould R., Howard R., Bullmore E. Fractional Gaussian noise, functional MRI and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2005;25(1):141–158. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.10.044. 15734351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shimizu Y., Barth M., Windischberger C., Moser E., Thurner S. Wavelet-based multifractal analysis of fMRI time series. Neuroimage. 2004;22(3):1195–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.03.007. 15219591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ivanov P.C., Amaral L.A., Goldberger A.L., Havlin S., Rosenblum M.G., Struzik Z.R., Stanley H.E. Multifractality in human heartbeat dynamics. Nature. 1999;399(6735):461–465. doi: 10.1038/20924. 10365957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ivanov P.C., Rosenblum M.G., Peng C.K., Mietus J., Havlin S., Stanley H.E., Goldberger A.L. Scaling behaviour of heartbeat intervals obtained by wavelet-based time-series analysis. Nature. 1996;383(6598):323–327. doi: 10.1038/383323a0. 8848043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hausdorff J.M., Gruendlinger L., Scollins L., O’Herron S., Tarsy D. Deep brain stimulation effects on gait variability in Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders. 2009;24(11):1688–1692. doi: 10.1002/mds.22554. 19554569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Delides A., Viskos A. Fractal quantitative endoscopic evaluation of the upper airway in patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery. 2010;143(1):85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2010.03.022. 20620624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldberger A.L., Amaral L.A., Hausdorff J.M., Ivanov P.C.h, Peng C.K., Stanley H.E. Fractal dynamics in physiology: alterations with disease and aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(Suppl. 1):S2466–S2472. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012579499. 11875196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Park Y., Lee K., Ziegler T.R., Martin G.S., Hebbar G., Vidakovic B., Jones D.P. Multifractal analysis for nutritional assessment. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e69000. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069000. 23990878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wallace D.C., Chalkia D. Mitochondrial DNA genetics and the heteroplasmy conundrum in evolution and disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2013;5(11):a021220. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021220. 24186072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Cecco M., Criscione S.W., Peterson A.L., Neretti N., Sedivy J.M., Kreiling J.A. Transposable elements become active and mobile in the genomes of aging mammalian somatic tissues. Aging. 2013;5(12):867–883. doi: 10.18632/aging.100621. 24323947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sedivy J.M., Kreiling J.A., Neretti N., De Cecco M., Criscione S.W., Hofmann J.W., Zhao X., Ito T., Peterson A.L. Death by transposition − the enemy within? BioEssays News and Reviews in Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology. 2013;35(12):1035–1043. doi: 10.1002/bies.201300097. 24129940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]