Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effect of tocilizumab (TCZ), an interleukin 6 receptor inhibitor, on humoral immune responses to immunisations in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods

Patients with RA with inadequate response/intolerance to one or more anti-tumour necrosis factor-α agents were randomly assigned (2:1) to TCZ 8 mg/kg intravenously every 4 weeks plus methotrexate (MTX) or MTX alone up until week 8. Serum was collected before vaccination at week 3, antibody titres were evaluated at week 8, and then all patients received TCZ+MTX through week 20. End points included proportion of patients responding to ≥6/12 pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23) serotypes (primary) and proportions responding to tetanus toxoid vaccine (TTV; secondary) at week 8.

Results

91 patients were randomised. At week 8, 60.0% of TCZ+MTX and 70.8% of MTX patients responded to ≥6/12 PPV23 serotypes, with insufficient evidence for any difference in treatments (10.8% (95% CI −33.7 to 12.0)), and 42.0% and 39.1%, respectively, responded to TTV. Two of three TCZ+MTX patients with non-protective baseline TTV antibody titres achieved protective levels by week 8. The safety profile of TCZ was consistent with previous reports.

Conclusions

Short-term TCZ treatment does not significantly attenuate humoral responses to PPV23 or TTV. To maximise vaccine response, patients should be up to date with immunisations before starting TCZ treatment.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier

Keywords: Methotrexate, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Vaccination

Introduction

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have increased risk of infection because of underlying disease and immunomodulatory therapies. Therefore, routine immunisations are important to reduce morbidity and mortality.1–3 However, RA treatments may reduce primary immune responses to vaccines and diminish anamnestic responses.4–6

Tocilizumab (TCZ), a humanised monoclonal antibody directed against soluble and membrane-bound interleukin 6 (IL-6) receptors,7 is widely approved for treating moderate-to-severe RA. Because TCZ may affect how IL-6 regulates T-cell activation and B-cell differentiation,8–13 understanding the influence of TCZ on vaccine responses is important for this vulnerable population.

In previous studies, TCZ treatment did not impair antibody response to the trivalent-inactivated influenza vaccine14 or the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPV23).15 VISARA is the first randomised controlled trial evaluating humoral immune responses to T-cell-dependent and T-cell-independent antigens, tetanus toxoid vaccine (TTV) and PPV23, respectively, in patients with moderate-to-severe RA treated with TCZ.

Methods

This two-arm, randomised, parallel-group, open-label, multicentre, phase IV study in patients with active RA receiving background methotrexate (MTX) treatment was conducted by 33 investigators at 35 centres in the USA. Patients were randomly assigned 2:1 to receive TCZ 8 mg/kg intravenously every 4 weeks plus MTX (7.5–25 mg/week; TCZ+MTX) or MTX alone through week 8 (figure 1). At week 3, serum was collected for measurement of prevaccination antibody levels, after which PPV23 (Pneumovax; Merck & Co) was administered as an intramuscular or a subcutaneous injection in the deltoid, and TTV (Adsorbed; Aventis Pasteur) was administered as an intramuscular injection in the opposite deltoid. At week 8 (5 weeks after vaccination), serum was collected for measurement of post-immunisation levels of antibodies against pneumococcal polysaccharide and tetanus toxoid. All patients then received TCZ+MTX through week 20.

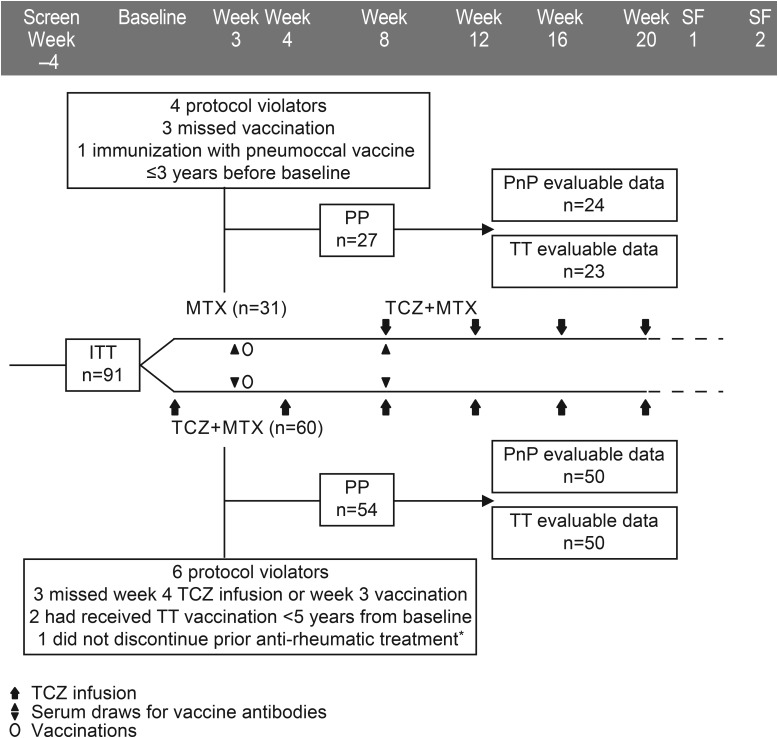

Figure 1.

Study flow for patients included in intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis. MTX, methotrexate; PnP, pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine; PP, per-protocol; SF, safety follow-up; TCZ, tocilizumab; TT, tetanus toxoid. *Before randomisation, did not discontinue etanercept for ≥2 weeks; infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab or golimumab for ≥8 weeks; or anakinra for ≥1 week.

Men and non-pregnant women aged 18–64 years with RA according to revised 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria16 for >6 months were enrolled. Patients had to have inadequate clinical response to antirheumatic therapies, including MTX, and inadequate clinical response or intolerance to ≥1 anti-tumour necrosis factor-α therapies. See online supplementary text for additional inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The primary end point was proportion of patients in each treatment group responsive to ≥6 of 12 anti-pneumococcal antibody serotypes at week 8 (5 weeks after vaccination and after two TCZ infusions in the TCZ+MTX group). A positive response to PPV23 was defined as a twofold or >1 mg/L increase from baseline at week 8. Secondary end points, safety assessments, analysis populations and antibody measurement methods are described in online supplementary text. No formal hypothesis testing was conducted. Descriptive statistics by treatment group and summaries of differences between treatment groups are presented along with 95% CIs for vaccine response only. A sample size of 91 patients was based on similar studies conducted with other RA treatments6 17 and 0% difference between treatment groups assuming an 80% response rate.

Results

Of 112 patients screened, 91 were randomly assigned to receive TCZ+MTX (n=60) or MTX alone (n=31). See online supplementary text for screening failures. The per-protocol (PP) population (figure 1) comprised 81 patients (54 in the TCZ+MTX group, 27 in the MTX group); 10 patients were excluded because of protocol violations. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics were generally well balanced between treatment groups, and mean baseline oral corticosteroid and MTX doses were comparable (see online supplementary table S1).

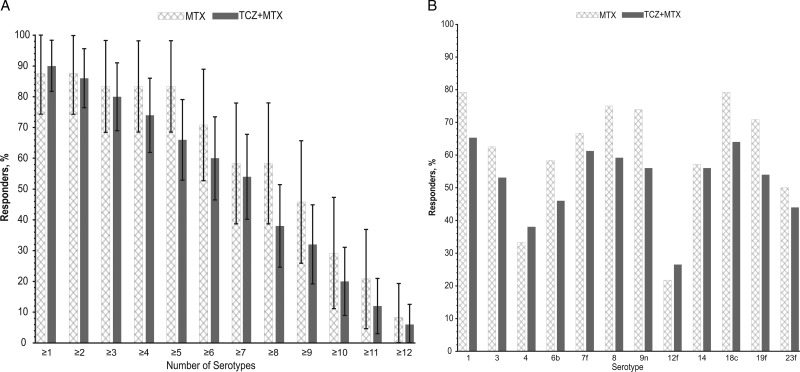

At week 8, the proportion of responders to PPV23 (primary end point) was numerically greater in the MTX group than in the TCZ+MTX group (70.8% vs 60.0%, respectively), with insufficient evidence for any difference between treatments (10.8 (95% CI −33.7 to 12.0); table 1). Overall, a greater proportion of MTX-treated than TCZ+MTX-treated patients responded to a combination of PPV23 serotypes (>1 up to 12). However, the 95% CIs for the proportion of responders were wide in both treatment groups for all combinations (figure 2A). Proportions of patients responding to individual anti-pneumococcal antibody serotypes were comparable between treatment groups (<10% difference between groups) for serotypes 3, 4, 7f, 12f, 14 and 23f, whereas the proportion of responders to serotypes 1, 6b, 8, 9n, 18c and 19f was lower (>10% difference) in the TCZ+MTX than in the MTX group (figure 2B).

Table 1.

Proportions of responders to pneumococcal polysaccharide and tetanus toxoid vaccines (week 8; per-protocol population)

| All patients* | Patients 18–50 years old | Patients 51–64 years old | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proportions of responders to ≥6 of 12 anti-pneumococcal antibody serotypes | ||||||

| MTX n=24 |

TCZ (8 mg/kg)+MTX n=50 |

MTX n=9 |

TCZ (8 mg/kg)+MTX n=18 |

MTX n=15 |

TCZ (8 mg/kg)+MTX n=32 |

|

| Responders, n (%) (95% CI) |

17 (70.8) (52.6 to 89.0) |

30 (60.0) (46.4 to 73.6) |

7 (77.8) (50.6 to 100.0) |

12 (66.7) (44.9 to 88.4) |

10 (66.7) (42.8 to 90.5) |

18 (56.3) (39.1 to 73.4) |

| Proportions of responders to tetanus toxoid vaccine | ||||||

| MTX n=23 |

TCZ (8 mg/kg)+MTX n=50 |

– | – | – | – | |

| Responders, n (%) (95% CI) |

9 (39.1) (19.2 to 59.1) |

21 (42.0) (28.3 to 55.7) |

– | – | – | – |

| Patients with x-fold increases in anti-tetanus toxoid antibody levels† | ||||||

| ≥2-fold, n (%) | 15 (65.2) | 36 (72.0) | – | – | – | – |

| ≥4-fold, n (%) | 9 (39.1) | 21 (42.0) | – | – | – | – |

MTX, methotrexate; TCZ, tocilizumab.

*Patients with evaluable data.

†Patients in the ≥4-fold group are also included in the ≥2-fold group.

Figure 2.

(A) Proportions of patients responding to pneumococcal serotype combinations from ≥1 to ≥12. Tocilizumab 8 mg/kg+methotrexate (tocilizumab (TCZ)+methotrexate (MTX); n=54) versus methotrexate (MTX; n=27). In this secondary end point analysis, the results show that, overall, a greater proportion of MTX-treated patients responded to serotype combinations. Error bars represent the 95% CIs, which indicate a notable degree of variation. (B) Proportions of patients responding to individual pneumococcal antigen serotypes. TCZ+MTX (n=54) versus MTX (n=27). In this secondary end point analysis, the results show that the proportion of responders to serotypes 3, 4, 7f, 12f, 14 and 23f was comparable (<10% difference) between that of the TCZ+MTX and MTX treatment groups, whereas the proportion of responders to serotypes 1, 6b, 8, 9n, 18c and 19f was lower in the TCZ+MTX treatment group than in the MTX treatment group (>10% difference). For serotypes 9n and 12f: MTX, n=23; for serotype 14: MTX, n=21; for serotypes 1, 3, 7f, 8 and 12f: TCZ+MTX, n=49.

When stratified by age, groups aged 51–64 years had ∼10% fewer responders regardless of treatment (table 1). Consistent with the primary end point, the proportion of patients in both age groups who responded to ≥6 of 12 anti-pneumococcal antibody serotypes was numerically lower in the TCZ+MTX than the MTX group, with overlapping CIs.

At week 8, similar proportions of patients in the TCZ+MTX (42.0%) and MTX (39.1%) groups responded to TTV (between-group difference 2.9% (95% CI −21.4% to 27.1%)); 95% CIs for the treatment groups were overlapping (table 1). In the TCZ+MTX group, three patients had non-protective anti-tetanus antibody titres at baseline (<0.1 IU/mL); two subsequently achieved protective levels by week 8. The proportion of patients achieving ≥2-fold and ≥4-fold increases in anti-tetanus toxoid antibody levels was greater in the TCZ+MTX group than in the MTX group (table 1). Concomitant treatment with oral corticosteroids did not appear to attenuate responsiveness to PPV23 or TTV (data not shown); however, this should be confirmed in larger studies.

The pharmacodynamic effect of TCZ was demonstrated by a marked and sustained reduction in C-reactive protein (CRP) levels from baseline through week 8 (see online supplementary table S2).

During the first 8 weeks of the study, differences in the safety profile between treatment groups were consistent with prescribing information for each drug. The incidence of adverse events (AEs) was higher in the TCZ+MTX group, driven primarily by events of sinusitis, nausea and headache. Most AEs were considered mild or moderate in intensity. Serious AEs (SAEs) were experienced by one patient in the MTX group and two patients in the TCZ+MTX group (see online supplementary table S3). During the first 8 weeks, no patients in the MTX group discontinued treatment because of an AE or disease flare. One patient in the TCZ+MTX group discontinued treatment on day 10 because of hypersensitivity and urticaria. No patients discontinued treatment because of lack of efficacy or worsening of RA. Over the 20 weeks of the study, 41 (68.3%) patients in the TCZ+MTX group experienced 116 AEs (upper respiratory tract infection, sinusitis, nausea, headache, nasopharyngitis and urinary tract infection were the most commonly reported), and five SAEs were reported in four patients. Five patients in the TCZ+MTX group discontinued treatment because of AEs. No malignancies or deaths were reported.

Discussion

IL-6 is a driver of B-cell maturation and plasma cell differentiation13; therefore, clinicians need to understand the impact of IL-6 blockade on immune response. Results of this study indicate that immune responses to PPV23 after TCZ+MTX treatment were slightly attenuated compared with MTX alone; 60.0% and 70.8% of patients, respectively, responded to ≥6 of 12 anti-pneumococcal antibody serotypes. Response to this T-cell-independent vaccine after TCZ treatment gave an evaluation of the impact of TCZ on specific immunoglobulin production to pneumococcal polysaccharide antigens. Similarly, numerically greater proportions of MTX-treated than TCZ+MTX-treated patients responded to multiple combinations (≥1–12) of pneumococcal antigen serotypes. The response to individual pneumococcal serotypes varied among patients in each treatment group. Numerically, the proportion of responders to serotypes 1, 6b, 8, 9n, 18c and 19f (generally associated with invasive pneumococcal disease and multidrug resistance) was greater in the MTX group, although these differences are of unknown clinical significance and the protective titre against each subtype is unclear. As expected, the immune response to PPV23 was attenuated in older patients. However, the difference in proportions of responders between older and younger subpopulations was similar in the two treatment groups.

Because most patients had detectable baseline anti-tetanus antibody titres, response to this T-cell-dependent vaccine after TCZ treatment gave an evaluation of the effect of TCZ on immunoglobulin G production by memory T-helper cells (anamnestic or recall response to TTV). The immune response to TTV after TCZ+MTX treatment was similar to that after treatment with MTX alone (42.0% vs 39.1%, respectively). The reduction in response rates observed with MTX was consistent with previous reports.6 Small differences were observed between treatment groups in the proportion of patients with ≥2- and ≥4-fold increases from baseline in TTV antibody levels at week 8 for patients with baseline antibody levels ≥0.1 IU/mL.

The rapid and sustained reduction in CRP levels from baseline confirmed that TCZ was pharmacologically active. Overall, the vaccines and randomised treatments were well tolerated. As expected, most AEs reported by patients randomly assigned to MTX occurred after week 8, when TCZ was added. The AE profile was consistent with the known TCZ safety profile.

While most patients with RA treated with TCZ 8 mg/kg—the highest approved dose—mounted a detectable immune response to PPV23 and TTV, levels of protective antibodies were poorly defined. A limitation is that vaccine response was measured after only two TCZ infusions; whether results would be similar with longer-term TCZ treatment is unknown. Although no specific safety concerns were identified after vaccination in patients treated with TCZ, data from this study do not change the current prescribing recommendations that patients be brought up to date with immunisations in accordance with current guidelines if possible before TCZ treatment is initiated.18 19

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Emma Shittu, PhD, who provided scientific analysis support and Karen Stauffer, PhD, and Maribeth Bogush, PhD, who provided writing services on behalf of F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Footnotes

Contributors: COB designed the study, recruited participants, collected, analysed and interpreted data, wrote the report, and approved the final draft. WR recruited participants, reviewed the report, and approved the final draft. AK recruited participants, reviewed the report, and approved the final draft. AH designed the study, analysed and interpreted data, reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final draft. RU analysed and interpreted data, wrote the report, and approved the final draft. MK designed the study, analysed and interpreted data, reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final draft.

Funding: This study was funded by Genentech-Roche. Funding for manuscript preparation was provided by F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Competing interests: COB has served as a consultant to Genentech/Roche and has received travel support in that capacity. WR has served as a consultant to UCB, BMS, Roche/Genentech/Savient, Takeda and Crescendo; he has also received speakers’ bureau fees for Abbott, UCB, Roche/Genentech, Takeda and Amgen. AK has served as a consultant to Genentech and has received grant support from Genentech. AH is an employee of Genentech. RU is an employee of Roche. Micki Klearman is an employee of and owns stock in Roche/Genentech.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The investigator at each site ensured that the study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and with Good Clinical Practice according to the regulations and procedures described in the protocol. Signed informed consent was obtained from all patients before any study-specific assessments or procedures were performed.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Smitten AL, Choi HK, Hochberg MC, et al. The risk of hospitalized infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2008;35:387–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, et al. 2012 update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biologic agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64:625–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Assen S, Agmon-Levin N, Elkayam O, et al. EULAR recommendations for vaccination in adult patients with autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:414–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kapetanovic MC, Saxne T, Sjoholm A, et al. Influence of methotrexate, TNF blockers and prednisolone on antibody responses to pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:106–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elkayam O, Caspi D, Reitblatt T, et al. The effect of tumor necrosis factor blockade on the response to pneumococcal vaccination in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2004;33:283–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bingham CO, III, Looney RJ, Deodhar A, et al. Immunization responses in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with rituximab: results from a controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:64–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mihara M, Kasutani K, Okazaki M, et al. Tocilizumab inhibits signal transduction mediated by both mIL-6R and sIL-6R, but not by the receptors of other members of IL-6 cytokine family. Int Immunopharmacol 2005;5:1731–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roldan E, Brieva JA. Terminal differentiation of human bone marrow cells capable of spontaneous and high-rate immunoglobulin secretion: role of bone marrow stromal cells and interleukin 6. Eur J Immunol 1991;21:2671–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muraguchi A, Hirano T, Tang B, et al. The essential role of B cell stimulatory factor 2 (BSF-2/IL-6) for the terminal differentiation of B cells. J Exp Med 1988;167:332–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muhammad K, Roll P, Seibold T, et al. Impact of IL-6 receptor inhibition on human memory B cells in vivo: impaired somatic hypermutation in preswitch memory B cells and modulation of mutational targeting in memory B cells. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1507–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morse L, Chen D, Franklin D, et al. Induction of cell cycle arrest and B cell terminal differentiation by CDK inhibitor p18(INK4c) and IL-6. Immunity 1997;6:47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kishimoto T, Taga T, Yamasaki K, et al. Normal and abnormal regulation of human B cell differentiation by a new cytokine, BSF2/IL-6. Adv Exp Med Biol 1989;254:135–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dayer JM, Choy E. Therapeutic targets in rheumatoid arthritis: the interleukin-6 receptor. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:15–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mori S, Ueki Y, Hirakata N, et al. Impact of tocilizumab therapy on antibody response to influenza vaccine in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:2006–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mori S, Ueki Y, Akeda Y, et al. Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccination in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving tocilizumab therapy. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1362–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1988;31:315–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mease PJ, Ritchlin CT, Martin RW, et al. Pneumococcal vaccine response in psoriatic arthritis patients during treatment with etanercept. J Rheumatol 2004;31:1356–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Actemra® (tocilizumab injection, for intravenous infusion). South San Francisco, CA: Genentech, Inc., 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.RoActemra 20 mg/mL concentrate for solution for infusion. Hertfordshire, UK: Roche Registration Ltd, 2010. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.