Abstract

Campylobacter jejuni, a microaerophilic foodborne pathogen, inescapably faces high oxygen tension during its transmission to humans. Thus, the ability of C. jejuni to survive under oxygen-rich conditions may significantly impact C. jejuni viability in food and food safety as well. In this study, we investigated the impact of oxidative stress resistance on the survival of C. jejuni under aerobic conditions by examining three mutants defective in key antioxidant genes, including ahpC, katA, and sodB. All the three mutants exhibited growth reduction under aerobic conditions compared to the wild-type (WT), and the ahpC mutant showed the most significant growth defect. The CFU reduction in the mutants was recovered to the WT level by complementation. Higher levels of reactive oxygen species were accumulated in C. jejuni under aerobic conditions than microaerobic conditions, and supplementation of culture media with an antioxidant recovered the growth of C. jejuni. The levels of lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation were significantly increased in the mutants compared to WT. Additionally, the mutants exhibited different morphological changes under aerobic conditions. The ahpC and katA mutants developed coccoid morphology by aeration, whereas the sodB mutant established elongated cellular morphology. Compared to microaerobic conditions, interestingly, aerobic culture conditions substantially induced the formation of coccoidal cells, and antioxidant treatment reduced the emergence of coccoid forms under aerobic conditions. The ATP concentrations and PMA–qPCR analysis supported that oxidative stress is a factor that induces the development of a viable-but-non-culturable state in C. jejuni. The findings in this study clearly demonstrated that oxidative stress resistance plays an important role in the survival and morphological changes of C. jejuni under aerobic conditions.

Keywords: Campylobacter, oxidative stress defense, VBNC

Introduction

Campylobacter jejuni is one of the leading foodborne pathogens worldwide and is frequently found in the intestines of a wide range of wildlife and domestic animals, particularly poultry (Lee and Newell, 2006; Humphrey et al., 2007). As a microaerophile, C. jejuni is sensitive to high oxygen concentrations in the atmosphere (Lee and Newell, 2006). However, ironically, C. jejuni is isolated from various environmental sources and foods in normal atmospheric conditions with high oxygen tension (Luber and Bartelt, 2007; Guerin et al., 2010; Trimble et al., 2013). Multiple factors have been reported to affect C. jejuni survival in oxygen-rich conditions. For example, pyruvate protects C. jejuni from high oxygen stress in aerobic conditions (Verhoeff-Bakkenes et al., 2008), and a combinational use of ferrous sulfate, sodium metabisulfite and sodium pyruvate in culture media increases the viability of C. jejuni (Chou et al., 1983). In addition, metabolic commensalism with Pseudomonas sp. in spoilage microflora in chicken meat is also known to affect the survival of C. jejuni under aerobic conditions (Hilbert et al., 2010).

Since oxygen easily moves across the membrane, oxygen concentrations within a cell are equivalent to those of immediate extracellular environments (Imlay, 2008). Bacterial growth in the presence of oxygen inevitably produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) that may damage intracellular macromolecules, such as DNA, proteins, and lipids; thus, bacteria are equipped with a range of oxidative stress defense systems to detoxify ROS (Storz and Imlay, 1999; Imlay, 2008). To reduce exposure to high oxygen tension, unlike aerobes, microaerophiles, and anaerobes live in habitats where oxygen levels are low (Imlay, 2008), but conserved oxidative stress resistance systems are still available in microaerophilic bacteria and even in obligate anaerobes (Chiang and Schellhorn, 2012). The most common ROS-detoxification enzymes would include alkyl hydroperoxide reductase, catalase, and superoxide dismutase (SOD; Imlay, 2008); alkyl hydroperoxide reductase converts organic peroxides to alcohols and detoxifies physiological levels of hydrogen peroxide (Seaver and Imlay, 2001; Parsonage et al., 2008), catalase decomposes hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen, and SOD dismutates superoxide to hydrogen peroxide and oxygen (Imlay, 2008). Bacteria often possess redundant forms of the ROS-detoxification enzymes. For example, three types of SOD (SodA, SodB, and SodC), and two catalases (KatG and KatE) are present in Escherichia coli (Storz and Imlay, 1999; Imlay, 2008). However, the C. jejuni genome harbors only single gene copies of sodB, katA, and ahpC (Parkhill et al., 2000; Atack and Kelly, 2009). By using three antioxidant mutants (ahpC, katA, and sodB) defective in the production of key ROS-detoxification enzymes in C. jejuni, in this study, we demonstrated that oxidative stress defense play an important role in survival and morphological changes in C. jejuni under aerobic conditions.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

Campylobacter jejuni NCTC 11168 (Parkhill et al., 2000) and its isogenic ahpC, katA, and sodB mutants and their complementation strains (Oh and Jeon, 2014) were used in this study. All C. jejuni strains were routinely grown on Mueller Hinton (MH) media at 42°C under microaerobic conditions (5% O2, 10% CO2, 85% N2). MH media were supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg ml-1) or chloramphenicol (25 μg ml-1), where required. For liquid culture of C. jejuni, an overnight culture on MH agar was resuspended in MH broth to an OD600 of 0.07, and the bacterial suspension was grown at 42°C microaerobically or aerobically with shaking at 200 rpm.

Measurement of Total ROS Level

The level of total ROS accumulation was measured by using the fluorescence dye CM-H2DCFA (Life Technologies). C. jejuni was prepared by growing in MH broth under the culture conditions described above. Samples were taken at predetermined time (0, 4, 8, and 12 h) and washed with PBS. After treatment with 10 μM CM-H2DCFA for 30 min at room temperature, fluorescence was measured with FLUOstar Omega (BMG Labtech, Germany). The fluorescence levels were normalized to protein amounts that had been determined with the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad).

Aerotolerance Test

Campylobacter jejuni was grown in MH broth under aerobic conditions as described above. Samples were collected after 0, 4, 8, and 12 h for serial dilution and bacterial counting. Occasionally, N-acetyl cysteine (an antioxidant) was added to the cultures to a final concentration of 1 nM.

Fluorescence Microscopic Analysis

After cultured in MH broth as mentioned above, C. jejuni samples (100 μl) were taken at 0 h and after 12 h culture. Samples were washed twice with PBS and stained with the LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacteria Viability Kit (Life Technologies). Samples were observed with a fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss M100, Germany), and image analysis was performed with AxioVision SE64 (Version 4, Carl Zeiss).

Determination of Protein Oxidation

Campylobacter jejuni strains were grown in MH broth for 12 h as described above. Bacterial cells were washed twice with PBS and disrupted with a sonicator (Bioruptor; Diagenode, USA). Disrupted bacterial samples were loaded onto a 15% polyacrylamide gel after adding a sample buffer. Proteins were transferred from the gel to a PVDF membrane, and carbonylated protein groups were detected immunologically using primary anti-DNP antibody (Sigma–Aldrich). Anti-rabbit-peroxidase antibody was used as the secondary antibody (KPL Inc., USA). Primary and secondary antibodies were used at a dilution of 1:1,000, and the blotting results were visualized with a 4CN Peroxidase substrate system (KPL Inc.).

Lipid Peroxide (LPO) Assay

Lipid peroxide levels were measured with a commercial kit (Cayman Chemical Co., USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, C. jejuni strains were cultured in MH broth for 12 h as described above. The bacterial samples were washed twice and resuspended in PBS buffer. After thorough mix with an equal volume of Extract R, and following addition of ice cold chloroform to each sample, the bottom chloroform layer was collected by centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 5 min at 0°C. Chloroform-extracted samples were mixed with chloroform–methanol. The LPO levels were measured by reading the absorbance at 500 nm after mixing with Chromogen. The results were normalized to the total protein amounts in each sample that were determined with the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad).

Determination of ATP Concentrations

The ATP concentrations were measured with a commercial kit (Sigma–Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. C. jejuni NCTC 11168 was grown in MH broth for 12 h as described above. Samples were washed twice with PBS and resuspended with the assay buffer. The bacteria samples were reacted with a substrate and ATP enzyme for 3 min at room temperature. The ATP concentrations were determined by measuring luminescence with FLUOstar Omega. The ATP concentrations were normalized to protein contents in the reaction.

PMA–qPCR

Prior to the assay, bacterial cells were washed twice with PBS and resuspended with 20 μM PMA (Biotium Inc., USA). After exposure to LED light (Biotium Inc.) for 15 min, genomic DNA was extracted by boiling, and the supernatants were used for qPCR. The qPCR assay was performed with 7500 Fast Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA). The amplification program consisted of one cycle at 95°C for 5 min and 40 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 45 s. The Cjr01 gene was used as a control to normalize the results (Hwang et al., 2012), and the data were analyzed by using the 2-ΔΔCt method. The primer sequences are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

The primer sequences used in this study.

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 16s rRNA_F | GGATGACACTTTTCGGAGC | Logan et al. (2001) |

| 16s rRNA_R | CATTGTAGCACGTGTGTC | Logan et al. (2001) |

| Cjr01_F | TCGAACGATGAAGCTTTTAG | Hwang et al. (2012) |

| Cjr01_R | TTGTCCTCTTGTGTAGGG | Hwang et al. (2012) |

Results and Discussion

Impact of ROS Accumulation on C. jejuni Viability under Aerobic Conditions

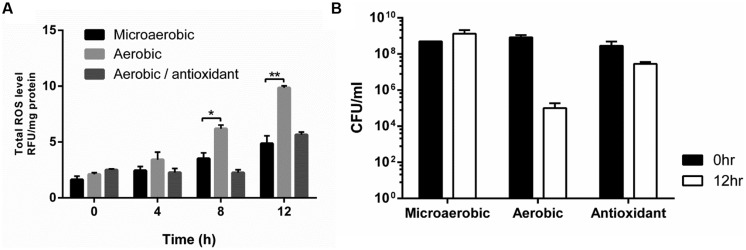

In contrast to favorable growth conditions available in the gastrointestinal tracts of poultry, such as low oxygen levels, high nutrients, and optimal growth temperatures (i.e., ~42°C), high oxygen tension in the atmosphere is one of the harsh environmental stress that C. jejuni should overcome to support its survival during the processing, transport, and storage of poultry products prior to foodborne exposure to humans and establishment of infections. Since ROS is inevitably generated as by-products of bacterial metabolisms in the presence of oxygen, we measured the levels of ROS accumulation in C. jejuni under aerobic conditions. The total ROS levels were significantly increased under aerobic conditions compared with microaerobic conditions (Figure 1A), and C. jejuni viability was substantially decreased (Figure 1B). To determine the impact of ROS accumulation on C. jejuni viability, the experiment was also performed in the presence of an antioxidant (1 nM N-acetyl cysteine). The addition of N-acetyl cysteine to aerobic cultures reduced the total ROS levels (Figure 1A) and restored C. jejuni viability similar to that under microaerobic conditions (Figure 1B). These results demonstrate that increased ROS accumulation affects C. jejuni viability under aerobic conditions.

FIGURE 1.

Total reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation (A) and Campylobacter jejuni viability (B) under microaerobic and aerobic conditions. N-acetyl cysteine was used as an antioxidant to a final concentration of 1 nM. The results show the means and SD of triplicate samples in a single experiment. The assays were repeated at least three times, and similar results were observed in all the experiments. Statistical analysis was performed with the Student’s t-test using GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software Inc., USA). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Growth Defects in ROS-Detoxification Mutants under Aerobic Conditions

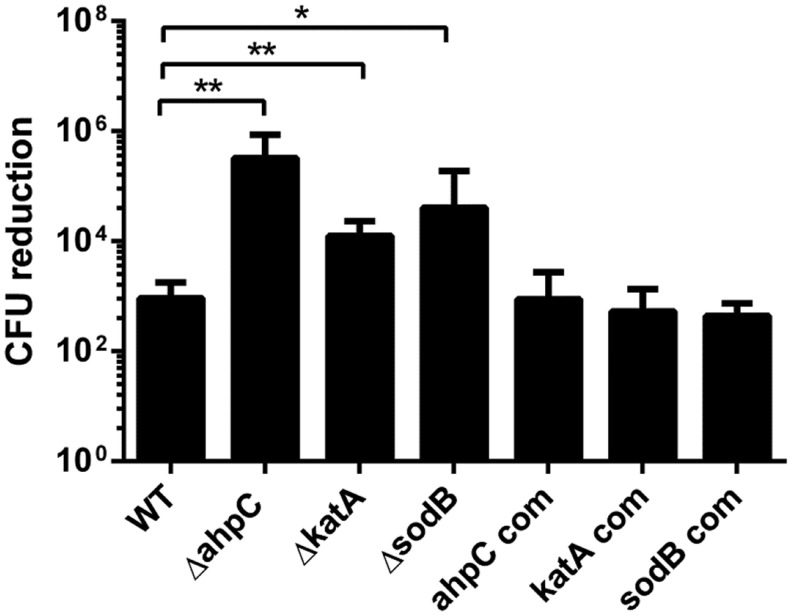

Campylobacter jejuni possesses only single gene copies of catalase (katA), alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (ahpC), and superoxide dismutase (sodB); they are primary enzymes for the detoxification of H2O2, organic peroxides, and superoxide, respectively. Since increased ROS accumulation reduced C. jejuni growth under oxygen-rich conditions (Figure 1), we investigated the contribution of these ROS-detoxification genes to C. jejuni survival under aerobic conditions. The growth of the katA, ahpC, and sodB mutants was significantly impaired under aerobic conditions, and the most substantial reduction was observed in the ahpC mutant (Figure 2). Complementation restored the aerotolerance of the mutants to the WT level (Figure 2), suggesting that the reduced aerotolerance in the mutants is directly related to their gene function in oxidative stress defense. A few studies have thus far shown the association of oxidative stress with the aerotolerance of Campylobacter. A mutation of fdxA, which is located upstream of ahpC and encodes the ferredoxin FdxA, affects the aerotolerance of C. jejuni (van Vliet et al., 2001). A double mutation of bcp and tpx, which encode the bacterioferritin comigratory protein (Bcp) and thiol peroxidase (Tpx), respectively, results in growth retardation under high aeration conditions (Atack et al., 2008). Baillon et al. (1999) reported that an ahpC mutation reduces aerotolerance in C. jejuni 81116. In this study, we showed that ahpC plays a more critical role than katA and sodB in the survival of C. jejuni under aerobic conditions (Figure 2). In other bacteria, antioxidant genes are differentially associated with aerotolerance depending on the bacterial species. A katA mutation increased the sensitivity of Helicobacter hepaticus to atmospheric oxygen (Belzer et al., 2011). In Bacteroides fragilis, mutations of oxidative stress defense genes, such as ahpCF and katB, rendered this obligate anaerobic bacterium more sensitive to aerobic stress than WT (Rocha et al., 1996). However, peroxide resistance genes, including ahpC, are not essential for aerotolerance in Streptococcus pyogenes, a catalase-negative facultative anaerobe (King et al., 2000).

FIGURE 2.

Growth defects in the ahpC, katA, and sodB mutants under aerobic conditions. The results show the means and SD of the levels of CFU reduction in triplicate samples after 12 h culture under aerobic conditions. The ahpC com, katA com, and sodB com are complementation strains of ahpC, katA, and sodB, respectively. The experiment was repeated three times and produced similar reduction patterns. The initial CFU levels were approximately 109 CFU ml-1 in all the tested stains. Statistical analysis was conducted by using the Student’s t-test. *P≤ 0.05, **P< 0.01.

A correlation between aerotolerance and the cellular levels of SOD has been reported; higher levels of SOD is produced in aerotolerant strains than oxygen-sensitive strains, and increased SOD production confers protection from high oxygen stress (Tally et al., 1977). The activity of SOD is essential for the aerotolerance of Porphyromonas gingivalis, an anaerobe implicated in chronic periodontitis, and mutations of SOD significantly reduced the viability of P. gingivalis in aerobic conditions (Nakayama, 1994). In this study, we also observed that a sodB mutation decreased aerotolerance in C. jejuni (Figure 2). However, a sodB mutation does not affect the growth of Campylobacter coli under aerobic conditions even with vigorous shaking at 150 rpm (Purdy et al., 1999). The differential impact of a sodB mutation on aerotolerance between C. jejuni and C. coli remains unexplained. However, the findings in this study suggest that the resistance to aerobic stress is different between C. jejuni and C. coli, although these two Campylobacter species are phylogenetically close to each other.

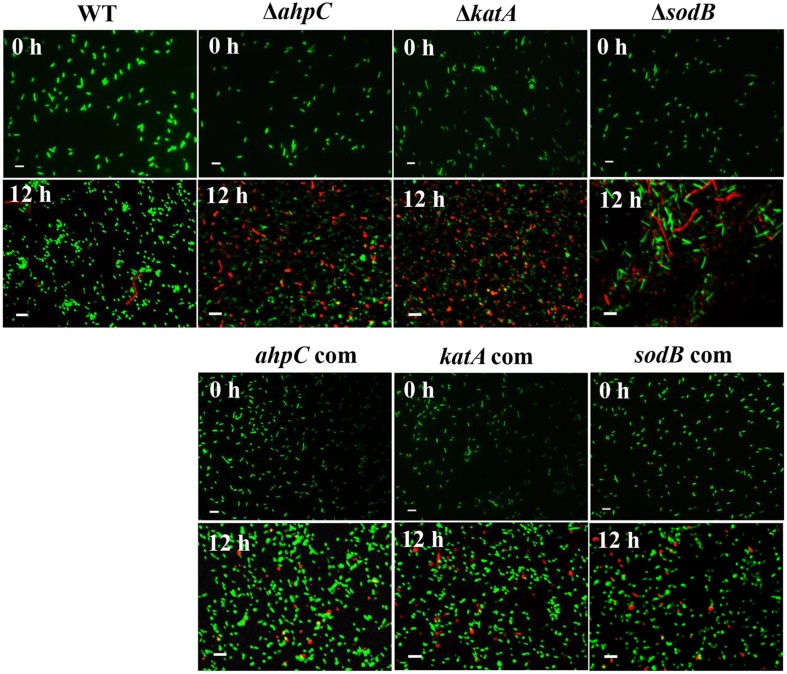

Morphological Changes in the Oxidative Stress Defense Mutants under Aerobic Conditions

The viability of C. jejuni was alternatively observed with fluorescence microscopy after the LIVE/DEAD staining. Consistent with the viability reduction under aerobic conditions (Figure 2), the population of red (i.e., dead) cells markedly increased in the oxidative stress defense mutants under aerobic conditions, whereas green (i.e., live) cells constituted the major population in WT (Figure 3). The emergence of coccoidal cells was observed in WT, ahpC, and katA mutants with substantial dwarfing in size (Figure 3). Interestingly, in contrast, the sodB mutant exhibited significantly elongated cellular morphology (Figure 3). Despite similar levels of viability reductions between the sodB mutant and the katA mutant (Figure 2), their bacterial morphologies were completely different under aerobic conditions (Figure 3). Complementation increased the live cell population in the mutants and restored the morphology of the mutants similar to WT (Figure 3). These results exhibit that C. jejuni undergoes significant morphological changes under aerobic conditions and that the antioxidant genes are associated with C. jejuni morphology.

FIGURE 3.

Morphological changes in the oxidative stress defense mutants under aerobic conditions. Samples were stained with the Live/Dead BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit (Life Technologies). Scale bar represents 2 μm. The images are representative of three independent experiments. The ahpC com, katA com, and sodB com are complementation strains of ahpC, katA, and sodB, respectively.

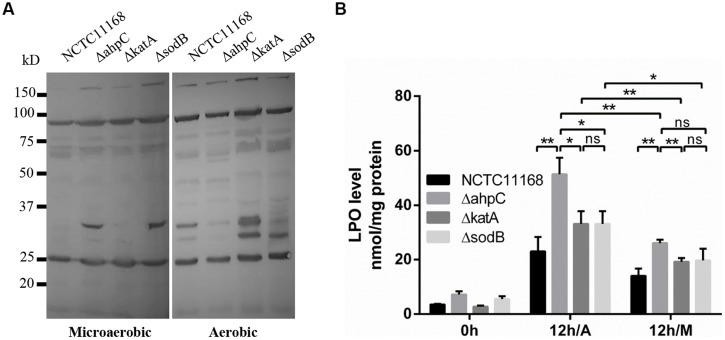

Lipid and Protein Oxidation under Aerobic Conditions

Since ROS may damage macromolecular cellular components, such as fatty acids and proteins, we analyzed the levels of protein and lipid oxidation in the oxidative stress defense mutants under aerobic conditions. Protein carbonylation occurs as a result of protein oxidation; thus, the protein carbonylation level is indicative of protein damage by oxidative stress. Protein carbonylation was detected by using anti-DNP antibody. Increased levels of protein carbonylation were observed under aerobic conditions in both WT and the mutants (Figure 4A). Particularly, the katA mutant exhibited markedly increased protein carbonylation, compared to WT and the ahpC and sodB mutants (Figure 4A). Lipid peroxidation was also significantly increased in the mutants than WT under microaerobic and aerobic conditions (Figure 4B). The most substantial increase in lipid peroxidation was observed in the ahpC mutant (Figure 4B), signifying the role of ahpC in the detoxification of lipid peroxides in C. jejuni. Based on these results, the substantial viability reduction in the ahpC mutant under aerobic conditions (Figure 2) is most likely to result from lipid oxidation in C. jejuni.

FIGURE 4.

Oxidation of proteins and lipids in the oxidative stress defense mutants under microaerobic and aerobic conditions. (A) Protein oxidation was measured by western blotting with monoclonal antibodies that recognize protein carbonylation. (B) Lipid peroxide (LPO) levels were increased in the oxidative stress defense mutants under aerobic condition. The LPO levels were determined after 12 h culture under aerobic conditions (12 h/A) and 12 h under microaerobic conditions (12 h/M). Results shown are the means and SD of triplicate samples. The experiment was repeated three times and all results produced similar results. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA using GraphPad Prism 6. *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01, ns, P > 0.05.

Emergence of Viable-But-Non-Culturable (VBNC) Cells under Aerobic Stress

Based on the morphological changes under aerobic conditions from spiral rods to coccoidal forms (Figure 3), we hypothesized that the emergence of coccoidal forms under aerobic conditions would be associated with oxidative stress. Exposure of C. jejuni to aerobic stress for 12 h significantly enhanced the formation of coccoid morphology, although C. jejuni is usually characterized by its typical helical rod shape. Counting of coccoid cells with fluorescence microscopy revealed that approximately 48.7% of C. jejuni cells established coccoid morphology after 12 h exposure to aerobic conditions, whereas only 2.6% of C. jejuni population turned to coccoidal forms under microaerobic conditions (Table 2). Interestingly, antioxidant treatment markedly reduced the population of coccoidal forms under aerobic conditions (Table 2), strongly indicating that oxidative stress is associated with the morphological changes. These results indicate that the formation of coccoidal cells was induced in C. jejuni under aerobic conditions through oxidative stress.

Table 2.

Formation of coccoidal Campylobacter jejuni under different oxygen conditions.

| Time | Microaerobic | Aerobic | Aerobic/antioxidant† |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 h | 2.4 ± 0.35 | 1.9 ± 0.35 | 1.0 ± 0.30 |

| 4 h | 4.9 ± 0.45 | 14.9 ± 2.19 | 1.3 ± 0.20 |

| 8 h | 5.3 ± 0.82 | 27.3 ± 1.83** | 4.6 ± 0.71 |

| 12 h | 2.6 ± 0.42 | 48.6 ± 5.18∗∗∗ | 8.2 ± 0.46 |

Percentage of coccoidal forms was obtained based on fluorescence microscopic observation, and the results show the mean and the SD of three different experiments.

†N-acetyl cysteine (1 nM) was used as an antioxidant.

Statistical analysis was performed with the Student’s t-test by comparison between the microaerobic and aerobic samples. **P < 0.01, ∗∗∗P< 0.001.

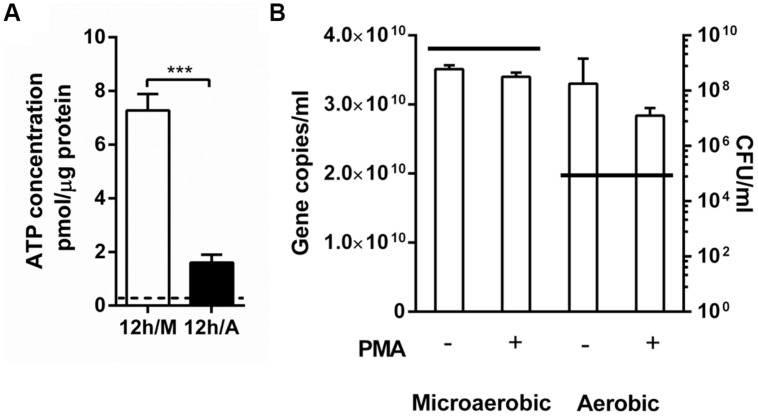

Since the dwarfing morphology of C. jejuni under aerobic conditions is similar to that of VBNC cells, we hypothesized that aerobic conditions may trigger the physiological switch of C. jejuni to a VBNC state. Although cells in a VBNC state do not grow on normal laboratory culture media, they are still viable and exhibit decreased intracellular ATP levels (Tholozan et al., 1999). The physiological activity of C. jejuni was evaluated by measuring the intracellular ATP concentrations. After 12 h when the majority of C. jejuni was in coccoidal forms, the ATP levels were significantly decreased in aerobic conditions compared with microaerobic conditions (Figure 5A), suggesting that coccoidal C. jejuni is still alive but physiologically inactive. In addition, the presence of VBNC cells was also determined by using PMA–qPCR. PMA is a DNA-binding dye and impermeable to the membrane of live cells. PMA modification of DNA by photolysis renders DNA non-amplifiable by PCR. Thus, PMA is often used to quantify DNA between live and dead cells (Nocker et al., 2006) and also to determine the levels of VBNC population (Dinu and Bach, 2013). The qPCR results from samples without PMA treatment reflect the population of whole cells, both live and dead, whereas PMA-treated sample shows only the population levels of live cells including VBNC cells. Based on gene copy numbers, there was a reduction in C. jejuni population in the PMA-treated samples compared to the non-PMA-treated samples after 12 h culture under aerobic conditions; however, the difference was not statistically significant (Figure 5B). This observation suggests that C. jejuni viability was not decreased significantly despite the substantial CFU reduction under aerobic conditions (Figures 2 and 5B), indicating that C. jejuni mostly lost its culturability, not viability, under the aerobic conditions. These findings strongly suggest that aerobic exposure induces the formation of VBNC cells in C. jejuni.

FIGURE 5.

Comparison of intracellular ATP levels and viability in C. jejuni between aerobic and microaerobic conditions. (A) The concentrations of intracellular ATP in C. jejuni after 12 h culture under microaerobic conditions (12 h/M) and aerobic conditions (12 h/A). The initial ATP level at 0 h is indicated with a dotted line. A Student’s t-test was carried out for statistical analysis. ∗∗∗P < 0.001. (B) Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed with or without PMA treatment after 12 h growth under different oxygen conditions. A horizontal line indicates the average CFU levels of the samples that were used for qPCR.

Bacteria in a VBNC state typically develop coccoid morphology by exposure to certain stress conditions. Despite being still alive, cells in a VBNC state do not grow on laboratory media and exhibit reduced energy consumption (Oliver, 2010). Upon removal of the stress, however, VBNC cells return to their original morphological shape and regain their physiological conditions and culturability. Therefore, the entry into a VBNC state is considered as an important strategy for bacteria to survive under stress conditions (Oliver, 2010). Many pathogenic bacteria, including C. jejuni, are known to form VBNC cells (Oliver, 2010). Importantly, pathogenic bacteria still maintain their infectivity in a VBNC state, because the resuscitation of VBNC cells enables pathogens to initiate an infection process (Oliver, 2010). C. jejuni cells in a VBNC state recover their ability to adhere to and invade human intestinal cells (Chaisowwong et al., 2012; Patrone et al., 2013) and to colonize animal intestines (Baffone et al., 2006). Multiple factors have been reported to induce a VBNC state in Campylobacter, including prolonged incubation at cold temperature (Chaisowwong et al., 2012), starvation (Klancnik et al., 2009), acid stress (e.g., formic acid at pH 4; Chaveerach et al., 2003), and polyphosphate kinase 1(PPK1; Gangaiah et al., 2009). In addition, our recent findings and previous studies of others have consistently shown the appearance of coccoidal forms in C. jejuni under aerobic conditions (Klancnik et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2015). In this study, we showed that aerobic culture increased the population of VBNC cells, whereas antioxidant treatment reduced the formation of VBNC cells (Table 2). These findings strongly indicate that oxidative stress induces a VBNC state in C. jejuni. Similarly, the impact of oxidative stress on the induction of a VBNC state has also been reported in Vibrio species. An oxyR mutant of Vibrio vulnificus, which is defective in catalase activity, is more likely to enter a VBNC state by cold temperatures compared to the parent strain, and the catalase activity has a direct correlation with culturability (Kong et al., 2004). Supplementation of culture media with H2O2-degrading compounds, such as catalase, enhances the resuscitation of VBNC cells in Vibrio parahaemolyticus (Mizunoe et al., 2000). By extrapolation from the reports in Vibrio, when C. jejuni is exposed to oxygen-rich conditions, this microaerophilic pathogenic bacterium may switch its physiological state to a VBNC form. In summary, the findings in this study demonstrate the impact of oxidative stress defense on C. jejuni growth and morphology under aerobic conditions. We still await further investigations to explain details about the molecular mechanisms for the formation of VBNC cells in C. jejuni under oxygen-rich conditions. Additionally, we performed the experiment in this study at 42°C with changes only in oxygen conditions (i.e., microaerobic vs. aerobic) to define the impact of aerobic stress on C. jejuni physiology. However, in the environment and poultry meat, C. jejuni would be likely to be exposed to aerobic conditions at lower temperatures than 42°C. In view of this, it would be an interesting future study to investigate the role of oxidative stress defense in C. jejuni survival under aerobic conditions at low temperatures in food or water settings.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), the Alberta Livestock and Meat Agency (ALMA), and the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI).

References

- Atack J. M., Harvey P., Jones M. A., Kelly D. J. (2008). The Campylobacter jejuni thiol peroxidases Tpx and Bcp both contribute to aerotolerance and peroxide-mediated stress resistance but have distinct substrate specificities. J. Bacteriol. 190 5279–5290 10.1128/JB.00100-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atack J. M., Kelly D. J. (2009). Oxidative stress in Campylobacter jejuni: responses, resistance and regulation. Future Microbiol. 4 677–690 10.2217/fmb.09.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baffone W., Casaroli A., Citterio B., Pierfelici L., Campana R., Vittoria E., et al. (2006). Campylobacter jejuni loss of culturability in aqueous microcosms and ability to resuscitate in a mouse model. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 107 83–91 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baillon M. L., Van Vliet A. H., Ketley J. M., Constantinidou C., Penn C. W. (1999). An iron-regulated alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (AhpC) confers aerotolerance and oxidative stress resistance to the microaerophilic pathogen Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 181 4798–4804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belzer C., Van Schendel B. A., Hoogenboezem T., Kusters J. G., Hermans P. W., Van Vliet A. H., et al. (2011). PerR controls peroxide- and iron-responsive expression of oxidative stress defense genes in Helicobacter hepaticus. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. (Bp.) 1 215–222 10.1556/EuJMI.1.2011.3.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaisowwong W., Kusumoto A., Hashimoto M., Harada T., Maklon K., Kawamoto K. (2012). Physiological characterization of Campylobacter jejuni under cold stresses conditions: its potential for public threat. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 74 43–50 10.1292/jvms.11-0305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaveerach P., Ter Huurne A. A., Lipman L. J., Van Knapen F. (2003). Survival and resuscitation of ten strains of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli under acid conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69 711–714 10.1128/AEM.69.1.711-714.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang S. M., Schellhorn H. E. (2012). Regulators of oxidative stress response genes in Escherichia coli and their functional conservation in bacteria. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 525 161–169 10.1016/j.abb.2012.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou S. P., Dular R., Kasatiya S. (1983). Effect of ferrous sulfate, sodium metabisulfite, and sodium pyruvate on survival of Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 18 986–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinu L.-D., Bach S. (2013). Detection of viable but non-culturable Escherichia coli O157: H7 from vegetable samples using quantitative PCR with propidium monoazide and immunological assays. Food Control 31 268–273 10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.10.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gangaiah D., Kassem Ii., Liu Z., Rajashekara G. (2009). Importance of polyphosphate kinase 1 for Campylobacter jejuni viable-but-nonculturable cell formation, natural transformation, and antimicrobial resistance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75 7838–7849 10.1128/AEM.01603-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerin M. T., Sir C., Sargeant J. M., Waddell L., O’Connor A. M., Wills R. W., et al. (2010). The change in prevalence of Campylobacter on chicken carcasses during processing: a systematic review. Poult. Sci. 89 1070–1084 10.3382/ps.2009-2213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilbert F., Scherwitzel M., Paulsen P., Szostak M. P. (2010). Survival of Campylobacter jejuni under conditions of atmospheric oxygen tension with the support of Pseudomonas spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76 5911–5917 10.1128/AEM.01532-1510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey T., O’Brien S., Madsen M. (2007). Campylobacters as zoonotic pathogens: a food production perspective. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 117 237–257 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang S., Zhang Q., Ryu S., Jeon B. (2012). Transcriptional regulation of the CmeABC multidrug efflux pump and the KatA catalase by CosR in Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 194 6883–6891 10.1128/JB.01636-1612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imlay J. A. (2008). Cellular defenses against superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77 755–776 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061606.161055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.-C., Oh E., Hwang S., Ryu S., Jeon B. (2015). Non-selective regulation of peroxide and superoxide resistance genes by PerR in Campylobacter jejuni. Front. Microbiol. 6:126 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King K. Y., Horenstein J. A., Caparon M. G. (2000). Aerotolerance and peroxide resistance in peroxidase and PerR mutants of Streptococcus pyogenes. J. Bacteriol. 182 5290–5299 10.1128/JB.182.19.5290-5299.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klancnik A., Guzej B., Jamnik P., Vuckovic D., Abram M., Mozina S. S. (2009). Stress response and pathogenic potential of Campylobacter jejuni cells exposed to starvation. Res. Microbiol. 160 345–352 10.1016/j.resmic.2009.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klancnik A., Vuckovic D., Plankl M., Abram M., Smole Mozina S. (2013). In vivo modulation of Campylobacter jejuni virulence in response to environmental stress. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 10 566–572 10.1089/fpd.2012.1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong I. S., Bates T. C., Hulsmann A., Hassan H., Smith B. E., Oliver J. D. (2004). Role of catalase and OxyR in the viable but nonculturable state of Vibrio vulnificus. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 50 133–142 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M. D., Newell D. G. (2006). Campylobacter in poultry: filling an ecological niche. Avian. Dis. 50 1–9 10.1637/7474-111605R.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan J. M., Edwards K. J., Saunders N. A., Stanley J. (2001). Rapid identification of Campylobacter spp. by melting peak analysis of biprobes in real-time PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39 2227–2232 10.1128/JCM.39.6.2227-2232.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luber P., Bartelt E. (2007). Enumeration of Campylobacter spp. on the surface and within chicken breast fillets. J. Appl. Microbiol. 102 313–318 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2006.03105.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizunoe Y., Wai S. N., Ishikawa T., Takade A., Yoshida S. (2000). Resuscitation of viable but nonculturable cells of Vibrio parahaemolyticus induced at low temperature under starvation. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 186 115–120 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb09091.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama K. (1994). Rapid viability loss on exposure to air in a superoxide dismutase-deficient mutant of Porphyromonas gingivalis. J. Bacteriol. 176 1939–1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nocker A., Cheung C. Y., Camper A. K. (2006). Comparison of propidium monoazide with ethidium monoazide for differentiation of live vs. dead bacteria by selective removal of DNA from dead cells. J. Microbiol. Methods 67 310–320 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh E., Jeon B. (2014). Role of alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (AhpC) in the biofilm formation of Campylobacter jejuni. PLoS ONE 9:e87312 10.1371/journal.pone.0087312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliver J. D. (2010). Recent findings on the viable but nonculturable state in pathogenic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34 415–425 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00200.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhill J., Wren B. W., Mungall K., Ketley J. M., Churcher C., Basham D., et al. (2000). The genome sequence of the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals hypervariable sequences. Nature 403 665–668 10.1038/35001088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsonage D., Karplus P. A., Poole L. B. (2008). Substrate specificity and redox potential of AhpC, a bacterial peroxiredoxin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105 8209–8214 10.1073/pnas.0708308105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrone V., Campana R., Vallorani L., Dominici S., Federici S., Casadei L., et al. (2013). CadF expression in Campylobacter jejuni strains incubated under low-temperature water microcosm conditions which induce the viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 103 979–988 10.1007/s10482-013-9877-9875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purdy D., Cawthraw S., Dickinson J. H., Newell D. G., Park S. F. (1999). Generation of a superoxide dismutase (SOD)-deficient mutant of Campylobacter coli: evidence for the significance of SOD in Campylobacter survival and colonization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 652540–2546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocha E. R., Selby T., Coleman J. P., Smith C. J. (1996). Oxidative stress response in an anaerobe, Bacteroides fragilis: a role for catalase in protection against hydrogen peroxide. J. Bacteriol. 178 6895–6903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaver L. C., Imlay J. A. (2001). Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase is the primary scavenger of endogenous hydrogen peroxide in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 183 7173–7181 10.1128/JB.183.24.7173-7181.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storz G., Imlay J. A. (1999). Oxidative stress. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2 188–194 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80033-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tally F. P., Goldin B. R., Jacobus N. V., Gorbach S. L. (1977). Superoxide dismutase in anaerobic bacteria of clinical significance. Infect. Immun. 16 20–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tholozan J. L., Cappelier J. M., Tissier J. P., Delattre G., Federighi M. (1999). Physiological characterization of viable-but-nonculturable Campylobacter jejuni cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65 1110–1116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimble L. M., Alali W. Q., Gibson K. E., Ricke S. C., Crandall P., Jaroni D., et al. (2013). Prevalence and concentration of Salmonella and Campylobacter in the processing environment of small-scale pastured broiler farms. Poult. Sci. 92 3060–3066 10.3382/ps.2013-03114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Vliet A. H., Baillon M. A., Penn C. W., Ketley J. M. (2001). The iron-induced ferredoxin FdxA of Campylobacter jejuni is involved in aerotolerance. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 196 189–193 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10563.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeff-Bakkenes L., Arends A. P., Snoep J. L., Zwietering M. H., De Jonge R. (2008). Pyruvate relieves the necessity of high induction levels of catalase and enables Campylobacter jejuni to grow under fully aerobic conditions. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 46 377–382 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02326.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]