Abstract

Financial exploitation and financial capacity issues often overlap when a gerontologist assesses whether an older adult’s financial decision is an autonomous, capable choice. Our goal is to describe a new conceptual model for assessing financial decisions using principles of person-centered approaches and to introduce a new instrument, the Lichtenberg Financial Decision Rating Scale (LFDRS). We created a conceptual model, convened meetings of experts from various disciplines to critique the model and provide input on content and structure, and select final items. We then videotaped administration of the LFDRS to five older adults and had 10 experts provide independent ratings. The LFDRS demonstrated good to excellent inter-rater agreement. The LFDRS is a new tool that allows gerontologists to systematically gather information about a specific financial decision and the decisional abilities in question.

Key terms: financial capacity, financial exploitation, assessment

The Person-Centered approach to work with older adults suffering from neurocognitive disorders is helping to support autonomy in these individuals (Fazio, 2013). The Person-Centered approach aims to build on the strengths of the individual, honor a person’s values and his or her choices and preferences (Fazio, 2013). Some of the underlying assumptions of this approach (Mast, 2011) are that (1) people are more than the sum of their cognitive abilities; (2) that traditional approaches over-emphasize deficits and under-emphasize remaining strengths; and (3) that it is important to understand the person’s subjective experience particularly in relation to the positive and negative reaction to the behaviors of others. Whitlach (2013) emphasized the importance of persons with neurocognitive impairment continuing to have choice; stressing that even people scoring well into the impaired range on the MMSE can provide valid and reliable responses. Mast (2011) described a new approach to assessment of persons with neurocognitive impairment: Whole Person Dementia Assessment. Whole Person Dementia Assessment seeks to integrate person-centered principles with standardized assessment techniques. Using a Whole Person Dementia Assessment approach we sought to create a new type of financial decision making rating scale that can be used in financial capacity assessments.

Our goals for this article are four-fold: (a) Review recent research on financial abuse and financial capacity; (b) Describe a new conceptual model for integrating the two aspects; (c) Introduce a new multidimensional, multiple-choice person-centered instrument, the Lichtenberg Financial Decision Rating Scale (LFDRS), which is based on a new conceptual model and is designed to aid assessment of the integrity of an elder’s financial judgment or financial decisional abilities; and (4) Describe a case study in which the LFDRS was used in an actual practice setting.

Financial Exploitation of Older Adults

Elder mistreatment is defined as intentional actions that cause harm or create serious risk of harm to an older adult by someone who stands in a trust relationship to the elder or is a caregiver (Dong & Simon, 2012). Elder mistreatment has been a focus of the federal government since the 1980s, when the Administration on Aging created a national center on elder abuse. In 1992 and again in 2006, amendments to the Older Americans Act broadened the definition of what constitutes elder abuse, though funding was not increased. Most recently, the Elder Justice Act (as part of the Affordable Care Act) was passed in 2011, requiring that federal courts recognize older adults’ right to be free from abuse and exploitation.

As part of an entire issue devoted to financial capacity and competency in our aging society Stiegel (2012) asserts that financial capacity and financial exploitation are “entwined”—that is, older adults are vulnerable to the potential loss of both (a) financial skills and financial judgment and (b) the ability to detect and therefore prevent financial exploitation. Nerenberg (2012) highlights the idea of “elder justice,” which holds that older adults have the fundamental right to live free from abuse, neglect, and exploitation. As critical as it is to protect older adults from financial exploitation, it is equally critical to protect their financial autonomy. Both under- and overprotection of older adults can damage their well-being and continued emotional growth. Under-protection can lead to gross financial exploitation and affect every aspect of the older adult’s life, including the ability to pay for essential resources. The dilemma is that overprotection can be equally costly: Many older adults have strong needs for autonomy and control, and to unnecessarily limit autonomy can result in increased anxiety and depression and shortened longevity, as well as damage the quality of their relationships.

Conrad et al. (2010) define financial exploitation of older adults as the illegal or improper use of an older adult’s funds or property for another person’s profit or advantage, and propose six domains of financial exploitation: (a) theft and scams, (b) abuse of trust, (c) financial entitlement, (d) coercion, (e) signs of possible financial abuse and (f) money-management difficulties. Thefts and scams involve taking an older adult’s monies without permission, either by outright stealing or by engaging in fraudulent activities (i.e., scams). Abuse of trust and financial entitlement, the second and third most serious acts, respectively, imply that there is an ongoing relationship between the parties.

Increasing Rates of Financial Abuse: Who is at Risk?

Older adults are financially exploited at a disturbing rate (Conrad, Iris, Ridings, Langley, & Wilber, 2010; Teaster, Roberto, Migliaccio, Timmerman, & Blancato, 2012). Compared to their 2009 study, Teaster et al., 2012 found significant increases in articles related to financial exploitation; 389 separate articles (print and online) about financial exploitation across three months. These described losses that totaled $530 million, which included $240 million taken by family members. Fifty-one percent of the cases involved exploitation by strangers.

Four recent random-sample studies have documented the alarming rates of financial exploitation and its correlates, while a fifth provides a new way to classify financial exploitation. For the most part, these studies gathered data on abuse of trust, coercion, and financial entitlement. Acierno et al. (2010) reported that of their sample of 5777 respondents, 5.2% of their sample of older adults had experienced financial exploitation by a family member during the previous year; 60% of the incidents involved a family member’s misappropriation of money. The authors also examined a number of demographic, psychological, and physical correlates of reported financial exploitation. Only two variables—deficits in the number of Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) the older adult could perform and nonuse of social services—were significantly related to financial exploitation.

Laumann, Leitsch, and Waite (2008) found that 3.5% of their sample had fallen victim to financial exploitation during the previous year. Younger older adults, ages 55–65, were the most likely to report financial exploitation. African Americans were more likely than Non-Hispanic Caucasians to report financial exploitation, while Latinos were less likely than Non-Hispanic Caucasians. Finally, participants with a romantic partner were less likely to report financial exploitation.

Beach, Schulz, Castle, and Rosen (2010) found that 3.5% of their sample reported having experienced financial exploitation during the six months prior to the interview, and almost 10% had since turning 60. The most common experience was signing documents the participant did not fully understand. The authors found that 2.7% of their sample believed that someone had tampered with their money within the previous six months; African American participants were more likely to report financial exploitation than were Non-Hispanic Caucasians. Risk for depression and having at least one ADL deficit were other correlates of financial exploitation.

Lichtenberg, Stickney, and Paulson (2013) focus on older adults’ experience of fraud (defined as causing financial loss using means other than robbery or theft). This was the first population-based study to use prospective data (i.e. 2002 Health and Retirement Survey (HRS) data was used to predict experience of fraud across 2003–2008) to predict any type of financial exploitation. Forty-four hundred older adults participated in an HRS sub-study, the 2008 Leave-Behind Questionnaire. The prevalence of fraud across the previous five years was 4.5%; based on measures collected in 2002. Age, education, and depression were found to be significant predictors of fraud. Using depression and social-needs fulfillment to determine the most psychologically vulnerable older adults, fraud prevalence in those with the highest depression and the lowest social-needs fulfillment was three times higher (14%) than the rest of the sample’s 4.1% prevalence (χ2=20.49; p<.001).

Jackson and Hafemeister (2012) compared pure financial exploitation and hybrid financial exploitation. Hybrid financial exploitation includes both financial abuse and either psychological abuse, physical abuse, or neglect. In cases of hybrid financial exploitation, the older adult victims were less healthy and more likely to be abused by those with whom they cohabitated. This important finding underscores the variability and heterogeneity of financial exploitation of older adults.

Impaired capacity and judgment in older adults is ever-present in many older adult financial exploitation cases. Several researchers who have studied financial exploitation highlight the need for effective, ongoing education about assessing capacity and more resources for evaluating an older adult’s vulnerability (Nerenberg, Davies, & Navarro, 2012). Nerenberg et al., 2012 also stress that differentiating between financial exploitation and legitimate transactions can be difficult, due to an older adult’s apparent consent (e.g., a signed document or putative gift). The lack of research on the assessment of demonstrated financial judgment or capacity for financial decision making hinders the creation of policies to address financial exploitation. Kemp and Mosqueda (2005) discuss the lack of validated measures to evaluate elder financial abuse and the importance of assessment by a qualified expert. They also strongly recommend the use of a team approach to assessment. Kemp and Mosqueda specifically highlight the need for a geriatric health care professional to provide expertise to criminal justice and Adult Protective Service professionals. The imperative for focusing more on financial exploitation for older adults is underlined by the fact that once faced with a loss of finances older adults do not have the time to recoup their losses, and tied to this, when forced to choose between basic living expenses and needed health care, the latter is often neglected leaving this group of older adults even more vulnerable to issues of frailty and comorbidity.

Financial Capacity in Older Adults

Research on financial capacity has emphasized the importance of protecting the autonomy and autonomous choices of capable older adults. A person is assumed to have financial capacity, defined here as the ability to manage “money and financial assets in ways consistent with one’s values or self-interest” (Flint, Sudore, & Widera, 2012), unless evidence to the contrary has been confirmed. Pinsker, Pachana, Wilson, Tilse, & Byrne (2010) propose that three abilities underlie financial capacity: (a) declarative knowledge (e.g., the ability to describe financial concepts), (b) procedural knowledge (e.g., the ability to write checks), and (3) judgment sufficient to make sound financial decisions. Since dementia is a key part of financial incapacity, Pinsker et al. conclude that comprehensive cognitive evaluation is essential for the assessment of financial capacity in older persons. Mental-health conditions such as depression, anxiety, and psychosis have also been found to affect capacity (Appelbaum & Grisso, 1988).

Marson (2001) argues that the impact of age-related dementia (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease) on financial capacity is one of the biggest challenges to financial autonomy. Marson created the Financial Capacity Instrument (FCI) and used it to compare financial capacity in cognitively intact older adults to that of older adults with conditions that ranged from Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) to mild or moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Marson identifies three elements of financial capacity; (a) specific financial abilities, (a) broad domains of financial activity, and (b) overall financial capacity. In his 2001 study, the degree of financial capacity was strongly linked to the person’s stage of Alzheimer’s disease. For instance, in examining domains of financial activity, 53%, 47%, and 13% of those in the mild stage of Alzheimer’s were rated as fully capable of, respectively, basic monetary skills, financial concepts, and financial judgment, while only 10%, 5%, and 0% of those in the moderate stage were rated as fully capable in the same domains. Fifty percent of those with mild stage Alzheimer’s disease were judged capable or marginally capable on financial judgment (as opposed to 13% who were rated as fully capable).

Sherod et al. (2009) investigated the neurocognitive predictors of financial capacity domains across 85 healthy normal elders, 113 older adults with MCI, and 43 with mild Alzheimer’s disease. Arithmetic ability was the single best predictor of scores on the Financial Capacity Instrument, predicting 27% of the variance in healthy elders and 46% in those with mild Alzheimer’s disease. In terms of self-assessment, Okonkwo et al. (2009) found that even those older adults in the earlier stages of cognitive decline were more likely to overestimate their cognitive skills than were normal controls. Financial judgment, however, remained an area in which those with MCI were as accurate in assessing their abilities as normal controls.

Kershaw and Webber (2008) created a financial capacity test similar to Marson’s Financial Capacity Instrument, the Financial Capacity Assessment Instrument (FCAI). The 38-item measure comprises five subscales: (a) everyday financial abilities, (b) financial judgment, (c) estate management (cognitive function related to financial tasks), (d) debt management, and (e) support resources. Initial reliability and validity data were promising. Kershaw and Webber (2008) report that the FCAI domains were significantly related to the MMSE and the Independent Living Scales Money Management subtest. Several studies have documented good inter-rater reliabilities and construct validity for the FCI scale, and there has been promising work with the FCAI scale as well. For those with MCI and mild Alzheimer’s disease, however, financial judgment had one of the lowest levels of inter-rater agreement.

One significant weakness of the otherwise excellent financial-domain assessment instruments in current use (e.g., Kershaw & Webber, 2008; Marson, 2009) is that they use neutral or hypothetical stimuli (e.g., “How could you be sure the price of a car is fair?”) rather than stimuli that examine the specific individual’s actual situation and financial judgment or transaction. Accordingly, valid and reliable tools are essential to adequately assess specific financial decision-making abilities, especially those needed for “sentinel financial transactions,” defined as transactions that can result in significant losses or harmful consequences. For example, an older woman PL worked with knew what a will was, and was able to describe how she wished to distribute her property. Using neutral stimuli would capture those intellectual factors but not capture the fact that her rationale was based on a paranoid delusion that she was cutting one daughter out of her will because she believed that this daughter was stealing from her. In fact, the court had discovered that her son, who lived with her, was in fact stealing from his mother and poisoning the relationship between the mother and daughter. In a second example, an older man came to the bank wishing to withdraw most of his savings (about $10,000) to give to a non-profit entity. The older man had only a vague awareness of what the non-profit was all about, how the gift might impact his own financial health, and was noted to have been driven to the bank by a representative from the non-profit. Clearly, tools that examine the specific financial decision in question would be extremely useful for determining the integrity of the older adults’ financial decisional abilities.

The Intersection of Financial Exploitation and Financial Capacity

Appelbaum and Grisso (1988) elaborated on the intellectual factors involved in capacity assessment: choice, understanding, appreciation, and reasoning. These kernel intellectual factors have been reiterated as fundamental aspects of decisional abilities (ABA/APA 2008). Although articulated originally for medical decision-making, the same intellectual factors apply to financial decisions. First, the older adult must be capable of clearly communicating his or her choice. Understanding is the ability to comprehend the nature of the proposed decision and provide some explanation or demonstrate awareness of its risks and benefits. Appreciation refers to the situation and its consequences, and often involves their impact on both the older adult and others. Appelabum and Grisso contend that the most common causes of impairment in appreciation are lack of awareness of deficits and/or delusions or distortions. Reasoning includes the ability to compare options—for instance, different treatment options in the case of health decision making. It also includes the ability to provide a rationale for the decision or explain the communicated choice.

Shulman, Cohen, and Hull (2005) examined 25 cases in which the testamentary capacity of an older adult had been challenged. Testamentary capacity, such as making a donation or signing a real estate contract (e.g., for a reverse mortgage), is heavily weighted toward financial-judgment skills—as opposed to actual management of finances or even performing cash transactions—due to the importance of appreciating one’s current financial standing. In 72% of the cases studied, a previous will had been radically changed. Signs of undue influence were documented in 56% of cases, and dementia was present in 40%. Other psychiatric and neurologic conditions were found in 28% of the cases. Flint et al. (2012) also found that impaired financial judgment is linked not only to cognitive impairment, but also to the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, including lack of awareness and delusional thinking. While the financial-exploitation literature has focused on risk factors for financial abuse and definitions for financial exploitation, the financial-capacity literature has emphasized financial knowledge and skills and, to a lesser extent, financial judgment. Yet in the context of a specific financial decision, it is essential to determine whether the older adult’s judgment is authentic and the integrity of his or her financial decisional abilities intact. We concluded that this calls for an instrument that is rooted in a Whole Person Dementia Assessment approach; using person-centered principles and standardized methods of assessment. Person Centered principles allow for the fact that even in the context of dementia, there may be important areas of reserve or strength, such as financial judgments based on long held values and beliefs. The Whole Person Dementia Assessment approach highlights the need for some standardization in how one assesses financial decision making, for example, using a person centered approach. The value of standardization is the opportunity to assess a domain across time, and across practitioners, and to have confidence that the same areas are being assessed. Only when an assessment is rooted in the sentinel financial transaction or decision in question can a third party render a decision as to financial capacity.

Research Questions

In this study we sought to answer three research questions:

Using two groups of experts for input and assistance, can a new conceptual model for understanding financial decision making be developed?

Using two groups of experts for input and assistance, can a new financial decision making instrument be created?

Using videos of test administration to older adults, can ratings based on the new instrument’s scale of financial decision making yield reliable ratings across the two expert groups?

Methods

Procedures for Developing the Model and Scale

Conceptual model

We developed an initial conceptual model by drawing on studies of decisional abilities in general and as specifically related to financial exploitation. Using the Concept Mapping Model (Conrad et al., 2010) we then assembled two groups of experts: six were engaged in financial-capacity work across the nation (i.e. psychologists and psychiatrists who do research and/or clinical work in the area of capacity assessment of older adults) and 14 were local and worked directly, on a daily basis, with older adults making sentinel financial decisions and transactions (e.g., law enforcement, bank personnel, adult protective services, financial planners, elder law attorneys). The national panel consisted of five psychologists and a psychiatrist. All of the panelists had been qualified as an expert in financial capacity assessment cases with older adults. Three of the six panelists have published extensively in the area of capacity assessment of older adults, and one in the Traumatic Brain Injury literature. The Institute of Gerontology at Wayne State University has co-sponsored conferences on legal, financial and psychosocial matters related to older adults. It is from contacts through these conferences that the second, local group was formed. Separate conference calls were held with each group to present the conceptual model for review. Based on their extensive feedback, the final conceptual model was refined and, in separate meetings with each group, finalized

Scale

In parallel with the development of the conceptual model, we also used the brain-storming technique described in the Concept Mapping methods (Kane & Trochim, 2007) with the expert groups to identify and choose items for the Lichtenberg Financial Decision Making Rating Scale (LFDRS). Originally 28 open-ended stems were proposed as potential questions. Based on their extensive feedback, a broader set of questions (77 in total) than we had originally proposed was created. It was further agreed that a multiple-choice format would be used for questions. Three months after the first set of conference calls, following multiple discusssions by the co-authors, and with our consultant Dr. Ken Conrad, the revised LFDRS was distributed and additional feedback elicited during a second set of conference calls. This resulted in only minor revisions, and the final version of the LFDRS was ready for testing soon after. Instructions for administration and scoring were also finalized at this time. The measure is in the early stages of being tested for reliability and validity and has yet to be widely released.

Procedures for Videotaping Interviews of Older Adults

Adults aged 60 and older were eligible to participate in a videotaped interview using the LFDRS if they had completed a major (relative to their circumstances) financial transaction or decision within the previous two months or if they were contemplating making a major financial transaction or decision in the next two months. All participants were referred by an elder-law attorney after obtaining the clients’ consent to do so. Approval for the videotaped interviews was obtained from the Wayne State University IRB, and all participants signed release forms approved by the university’s Office of the General Counsel. One of the authors (PL) performed all of the interviews. Interviews varied in length from 15 to 40 minutes; with the majority running 23–28 minutes. The instructions to the participants were as follows: “I am going to be asking you a number of questions related to your financial situation and financial decision making. For each question there will be multiple-choice answers. If any of the questions are confusing or unclear, please tell me.”

Participants

Five participants (all assigned pseudonyms), who are briefly described here, completed the LFDRS on videotape:

Participant #1: Deanna is a 65-year-old single, retired mother of one adult child. She has a master’s degree and had retired within the previous six months. The decision being weighed was whether to set up a trust and change her will so that her son—who lives with her and attends graduate school—would be her Durable Power of Attorney for Finances (DPOA). Specifically, she was considering a “springing” DPOA, which does not require that two physicians designate her as incapacitated. Deanna currently reports no significant current health problems.

Participant #2: Kathy is a 70-year-old single, retired woman with no children. She has an associate’s degree, and worked as a secretary during her career. Kathy suffered from bipolar disorder, for which she had experienced an acute episode and been hospitalized six years prior to the LFDRS interview. The decision being weighed was whether to change her will so that one of her nieces will no longer be included in her estate.

Participant #3: Shirley is a 60-year-old married woman who had been seen by a neurologist two weeks prior to her LFDRS interview and received a diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s disease, mild stage. She and her husband have one adult son. Shirley completed high school and has been a homemaker since her marriage. Three weeks prior to her LFDRS interview, she purchased an annuity.

Participant #4: Tim is a 61-year-old married factory worker with one child. He has a high school education and is married to Shirley (Participant #3). On the advice of his financial advisor and separate from Shirley, he had recently purchased an annuity with a nursing-home rider. Afterward, Tim learned from his attorney that the annuity could be a threat to his financial assets.

Participant #5: Jan is a 76-year-old widow with two adult children. She has a high school education and worked as a bookkeeper until her retirement 10 years earlier. Jan recently established a special-needs trust for one of her adult sons, who is emotionally disturbed.

Reliability Ratings

The five videotaped interviews were rated by five experts from each of the two expert groups for a total of 10 raters. Five experts were psychologists trained in clinical gerontology and experienced in older adult capacity assessments, and the remainder also worked extensively with older adults and included two attorneys, one Adult Protective Service worker and two financial planners. The videotaped interviews were sent to the raters and they rated them independently. The raters were given the LFDRS written instructions and were given three weeks to rate the interviews. Raters were instructed to view each interview and rate the integrity of a participant’s financial decisional abilities as fully capable, marginally capable, or not capable. Following the methods of Marson’s (2009) study excellent judgment agreement was defined as 100% agreement (“exact”), and very good judgment was defined as 80% or greater agreement.

Results

A New Conceptual Model for Financial Decision Making

A new model was created and included contextual factors, intellectual factors and values. The contextual factors were chosen from studies of financial exploitation. Conrad et al. (2010) identified themes of financial coercion and financial entitlement as part of financial exploitation. These are included in contextual factors of past financial exploitation and undue influence. Different studies highlighted different aspects of the importance of financial situational awareness and psychological vulnerability; from Beach and Schultz’s (2010) predictors of financial exploitation to Lichtenberg et al.’s (2013) work on scams. Intellectual factors were drawn from the 25-year tradition of decisional abilities research (Appelbaum and Grisso, 1988) and echoed by more recent work (ABA-APA, 2008; Sherod et al., 2009). The ABA-APA Handbook for Psychologists to assess diminished capacity also highlighted the importance of an older adult’s values.

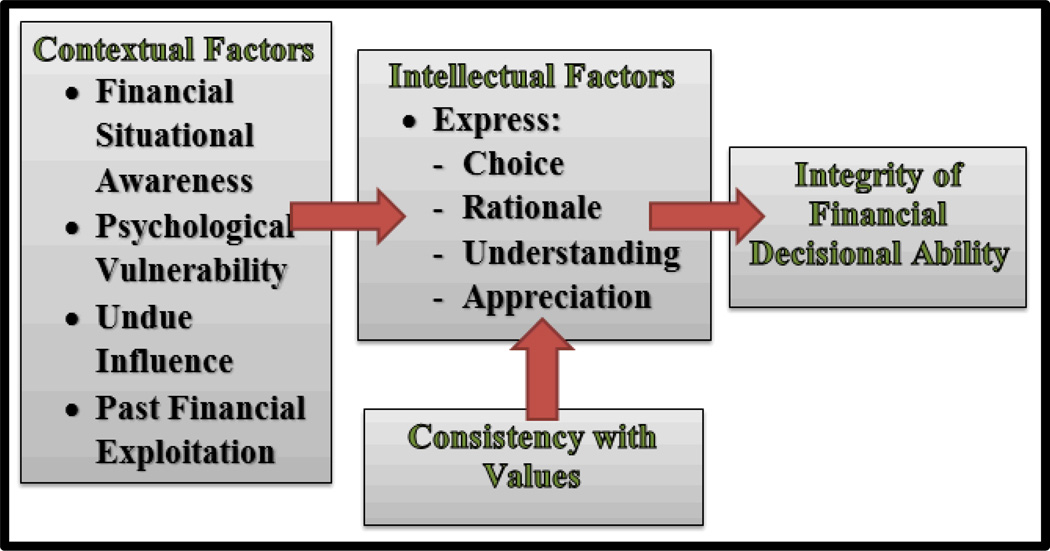

As can be seen in Figure 1, contextual factors include Financial Situational Awareness (FSA); Psychological Vulnerability (PV), which includes loneliness and depression; Undue Influence (I); and Financial Exploitation (FE). Contextual factors, as illustrated by the model, directly influence the intellectual factors associated with decisional abilities for a sentinel financial transaction or decision.

Figure 1.

Key Components of the Financial Decisional Abilities Model

Intellectual factors refer to the functional abilities required for financial decision-making capacity and include an older adult’s ability to (1) express a choice (C), (2) communicate the rationale (R) for the choice, (3) demonstrate understanding (U) of the choice, (4) demonstrate appreciation (A) of the relevant factors involved in the choice, and (5) make a choice that is consistent with past values (V). Intellectual factors—unless they are overwhelmed by the impact of contextual factors—are the most proximal and central to determining the integrity of financial decisional abilities.

Lichtenberg Financial Decision Making Rating Scale (LFDRS) Construction

The final scale consists of 61 multiple-choice questions that were asked of all participants. Depending on the answers to certain items, it is possible to be asked up to 17 additional questions. The questions are presented in separate sections that measure Financial Situational Awareness (18 questions; including some undue influence and financial exploitation), Psychological Vulnerability (12 questions), Current Financial Transaction (20 questions; including intellectual factors) and a final section on undue influence and financial exploitation (11 items). Sample items from the LFDRS are shown in Table 1. Examiners can score single items according to awareness and accuracy or examiner rated risk. Single items are not tallied; rather the examiner uses the information from the entire scale to determine a single judgment about integrity of financial decisional abilities.

Table 1.

Sample Items from the Lichtenberg Financial Decision Making Rating Scale

| Financial Situational Awareness |

| • What are your current sources of income? |

| • How worried are you about having enough money to pay for things? |

| • Who manages your money day to day? |

| • Do you regret or worry about financial decisions you have made recently? |

| • Are you helping anyone financially on a regular basis? |

| • Have you gifted or lent money to someone in the past couple of year? |

| Psychological Vulnerability |

| • How often do you wish you had someone to talk to about financial decisions or plans? |

| • Have you recently lost someone who was a confidante? |

| • How often do you feel downhearted or blue about your financial situation or decisions? |

| • Is your memory, thinking skills, or ability to reason with regard to finances worse than a year ago? |

| • When it comes to making financial decisions, how often are you treated with less courtesy and respect than other people? |

| Sentinel Financial Decision/Transaction |

| • What current major financial decisions or transactions are you intending to make? |

| • What are your personal (financial) goals with this transaction? |

| • Now and over time, how will this decision and/or transaction impact you financially? |

| • How much risk is there that this transaction could result in a loss of funds? |

| • Who will be adversely affected by the current decision/transaction? How will they react? |

| • To what extent did you consult with anyone before making the financial decision? |

| • Who did you discuss this with? |

| • Would someone who knows you well say this decision was unusual for you? |

| Financial Exploitation |

| • Have you ever had checks missing from or out of sequence in your checkbook? |

| • Do you have a credit or debit card that you allow someone else to use? |

| • Has anyone ever signed your name to a check? |

| • How often in the past few months has someone asked you for money? |

| Undue Influence |

| • Have you had any conflicts with anyone about the way you spend money or to whom you give money? |

| • Has anyone asked you to change your will? |

| • Has anyone recently told you to stop getting financial advice from someone? |

| • Was this transaction your idea or did someone else suggest it? |

| • Did this person drive or accompany you to carry out this financial transaction? |

Inter-rater reliability Results

Table 2 presents details for the inter-rater judgment agreement for the gerontology experts using the LFDRS. Raters were told ahead of time about the specific financial decision in question but were not given any medical or personal background information on the older adults that were interviewed. The raters’ judgment was based solely on their observations of the LFDRS interview. Instructions for scoring the integrity of the financial decisional abilities were as follows: “Overall decisional abilities are a clinical judgment based on both the contextual and intellectual factors. In a case with few concerns raised by contextual factors, scores on the intellectual factors would determine the overall decisional ability judgment. An interviewer may determine, however, that contextual factors, such as undue influence and/or psychological vulnerability, overwhelm the individual’s intellectual factors and, as a result, use contextual factors and intellectual factors in making an overall decision. Overall decisional abilities are rated on a 3-point scale.

0 = Lacks decisional abilities

1 = Has marginal decisional abilities to make this decision/transaction

2 = Has full decisional abilities to make this decision/transaction

Table 2.

Inter-Rater Judgment Agreement for the 10 Experts using the LFDRS.

| Observed | % Agreement | |

|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | 10/10 Fully Capable | 100% |

| Case 2 | 10/10 Fully Capable | 100% |

| Case 3 | 10/10 Not Capable | 100% |

| Case 4 | 8/10 (8 Fully Capable; 2 Marginally Capable) | 80% |

| Case 5 | 9/10 (9 Fully Capable; 1 Marginally Capable) | 90% |

There was significant enough challenge in the cases that raters were not all in agreement. In cases one, two and three there was perfect agreement, with cases one and two being deemed fully capable and case three being judged as not capable. In case four there was 80% agreement. In this case eight of the raters judged Tim fully capable and two of the ten judged Tim marginally capable. These latter two experts believed that Tim did not fully understand the decision he made. Finally in case 5 there was 90% agreement, with nine raters judging Jan fully capable and one judging her marginally capable.

Case Studies

The cases below are used to illustrate the scale in use. One of the cases was referred by an attorney who wished to get one of the author’s (PL) input on his client’s testamentary capacity while the other was an active case in the probate courts. The actual client demographic and occupational details have been changed to protect anonymity of the clients. Both, however, gave their consent to the case reports below.

Case #1 TF

TF was a 78 year old, widowed (no children), retired small business owner who went to his attorney after TF’s nephew began conservatorship proceedings, despite the fact that TF’s bills and finances were being taken care of by a Durable Power of Attorney that TF had named some years earlier, and had worked closely with during the previous year. TF’s personal attorney referred TF for a capacity evaluation in order to determine if TF needed conservatorship, and if he had testamentary capacity as he wished to change his will vis a vis his nephew. TF fell eight months before the evaluation, breaking his lower leg, and underwent long term rehabilitation. During the rehabilitation it was discovered that he exhibited memory problems. He was seen by a neurologist and neuropsychologist who diagnosed him with Alzheimer’s disease, mild stage. The neuropsychologist performed a capacity assessment for financial decision making. TF described his hobbies as photography, travel, sports, especially hockey, and outdoor activities of all kinds. He denied any history of heavy drinking and denied any mood difficulties or depression.

Cognitive Assessments

The neuropsychologist completed the first capacity assessment with TF. He completed a cognitive assessment, and administered the money management section of the Independent Living Scale test. TF’s cognitive profile was entirely consistent with someone presenting with dementia. On a test of reading he scored in the above average range. TF displayed several areas of strength including orientation to time, person and place, basic attention, visual spatial attention and basic problem solving and visual integration skills. He also displayed two areas of deficits; moderate to severe memory impairments for new information, even when that information was encoded using multiple methods (i.e. touch, vision, naming objects), and he demonstrated mild executive functioning deficits across verbal and visuospatial tasks. During the assessment TF was found to score in the low average range in money management skills. Based on these money management findings it was concluded that TF “lacks capacity to make informed decisions pertaining to complex medical, legal and financial matters.”

A second capacity assessment was performed two months later, by a different psychologist. Cognitive testing, using a battery very similar to the one used in the first assessment, was performed, and since the capacity in question hinged on financial decision making abilities, the LFDRS was also administered. TF was a good historian for his medical conditions; describing both the fall and the lengthy rehabilitation process he underwent. He also described his businesses in great detail, and these were later verified by his long term attorney. He denied any cognitive problems, and described his as a blessed life.

The findings of the second cognitive assessment were very similar to those of the first assessment. The LFDRS results, however, led to a different conclusion in this case of capacity than did those of the ILS. The LFDRS is made up of five subscales, with the first being Financial Situational Awareness. Answers to questions on this subscale revealed that TF already had designated someone to manage his day to day finances, and that he was very satisfied with the arrangement. He demonstrated no psychological vulnerability such as loneliness, depression or anxiety, on the second subscale.

TF clearly communicated that he did not want a conservator and that he wanted to change his will and Trust. He stated that this was his own idea. He recognized that his family members would receive less money than he previously planned, and that they would be hurt and angry about his decision. TF stated that this change was due to his nephew’s behavior, which he thought was motivated by his nephew’s greed and sense of financial entitlement. TF had not previous experiences or concerns about financial exploitation and indicated that his long time attorney was his confidant. TF believed that his attorney protected him from any susceptibility to undue influence.

Summary and Conclusions

Although the two cognitive assessments revealed very similar findings, different conclusions about financial capacity were reached. Using a traditional model of testing financial skills and knowledge, one psychologist determined that TF lacked capacity because his money management skills were below average. Using a person-centered approach, and focusing on financial decision making, the second psychologist found that TF had the decisional abilities to continue to choose to work with his DPOA for finances, and that he had testamentary capacity. The LFDRS demonstrated that TF had knowledge of his finances, and that he had taken steps to obtain assistance for day to day money management issues. Further, the LFDRS demonstrated that TF communicated his understanding, rationale, and appreciation for the choice to continue with his DPOA and to change his will due to his belief that his nephew wanted to exploit his finances.

Discussion

The Whole Person Dementia Assessment (Mast, 2011) approach we used is entirely consistent with the tools developed by the MacArthur Civil Competence Project that lasted from 1989–1997. One of those tools is the MacArthur Competence Assessment Tool for Treatment (MacCAT-T) (Grisso & Appelbaum, 1998). In their introduction to the tool they stated that the “MacCAT-T was designed to be consistent with a basic maxim in the legal definition of competence: No particular level of ability is always associated with competence or incompetence… (p.2).” The MacArthur tools used many of the concepts we now identify with a person-centered approach. In the current paper we aimed to advance the understanding of older adults’ capacity for financial decision making and financial judgment, both conceptually and empirically, and thereby improve gerontologists’ ability to assess financial capacity and to assess vulnerability to financial exploitation. Whereas the financial exploitation literature primarily concerns itself with risk factors and protection of older adults, those who study financial capacity are primarily concerned with the integrity of decisional abilities and autonomy concerns. There is a significant disconnect in clinical gerontology capacity and financial exploitation work with older adults; a failure to integrate concepts and central ideas from both fields of study and practice. Financial capacity cases, (i.e. largely the domain of Probate judges) and financial exploitation cases (i.e. police, prosecutors) require the clinical gerontologist to assess and report on whether the choice of an individual meets the requirement for decisional abilities. Instruments such as the Financial Capacity Instrument (Marson, 2001) or even a thorough neuropsychological evaluation do not specifically assess the financial decision in question, or the decisional abilities that underlie the decision. Prosecutors and police rarely assess decisional abilities further if an older adult claims to have given money freely to someone else and criminal justice professionals often not recognize that choice is only one of the intellectual factors needed to demonstrate capable decisional abilities. The gap in clinical gerontology calls for the creation of a new set of tools that can systematically gather information about the older adult’s financial decisions and decisional abilities in question.

A conceptual model was created to describe the relationships between contextual factors, long-held values, and intellectual factors. The LFDRS was created as a measure that includes all aspects of the conceptual model and will assist in assessing the financial decisional abilities of the older adult who is considering a financial transaction. The conceptual model includes contextual factors that have been identified in the financial-exploitation literature and through practice—financial awareness, psychological vulnerability, past financial exploitation, and undue influence—and integrates these with the intellectual factors of choice, understanding, appreciation, and reasoning, while also considering long-held values.

Inter-rater judgment agreement was promising with 47 of the 50 ratings (94%) being identical. In only one of the cases did inter-rater agreement drop to 80%, which is still considered good agreement when using Marson’s criteria. The cases in which there was a lack of perfect agreement were instructive. In one case, Tim, made a decision based on a financial advisor’s advice, and only later did he discover that this choice might actually end up costing him and his family money in the long run. Two of the reviewers rated his financial decisional abilities as marginally capable.

Convergent and construct validity data do not yet exist. By their very nature, capacity assessment and the assessment of financial exploitation often rely on expert clinicians’ ratings and findings. Evaluation of an older adult’s capacity for financial decision making is often the key aspect integral to the assessment of capacity and/or financial exploitation. The case study illustrates how the LFDRS can be used in practice, in conjunction with more established neuropsychological assessments.

Contributor Information

Peter A. Lichtenberg, Wayne State University, Institute of Gerontology, 87 E Ferry Street, Detroit, MI 48202, 313-664-2633 (phone), 313-663-2667 (fax), p.lichtenberg@wayne.edu.

Jonathan Stoltman, Wayne State University, Institute of Gerontology, 87 E Ferry Street, Detroit, MI 48202

Lisa J. Ficker, Wayne State University, Institute of Gerontology, 87 E Ferry Street, Detroit, MI 48202

Madelyn Iris, CJE SeniorLife, 3003 West Touhy Avenue, Chicago, IL 60645

Benjamin Mast, University of Louisville, Department of Psychology and Brain Sciences, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY 40292

References

- American Bar Association Commission on Law and Aging and American Psychological Association. Assessment of older adults with diminished capacity: A handbook for psychologists. Washington, DC: American Bar Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Acierno R, Hernandez MA, Amstadter AB, Resnick HS, Steve K, Muzzy W, Kilpatrick DG. Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: The National Elder Mistreatment Study. Journal Information. 2010;100(2) doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.163089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. New England Journal of Medicine. 1988;319:1635–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812223192504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker RR, Lichtenberg PA, Moye J. A practice guideline for assessment of competency and capacity of the older adult. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1998;29:149–154. [Google Scholar]

- Beach SR, Schulz R, Castle NG, Rosen J. Financial exploitation and psychological mistreatment among older adults: Differences between African Americans and Non-African Americans in a population-based survey. The Gerontologist. 2010;50(6):744–757. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad KJ, Iris M, Ridings JW, Langley K, Wilber KH. Self-report measure of financial exploitation of older adults. The Gerontologist. 2010;50(6):758–773. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Simon MA. Elder abuse: Existing national policies and programs to defend the rights and safety of older adults. Public Policy and Aging Report. 2012;22:1–7. Retrieved from http://www.geron.org/policy-center/policy-publications/public-policy-and-aging-report?start=1. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio S. The individual is the core—and key—to person-centered care. Generations. 2013;37(3):16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Flint LA, Sudore RL, Widera E. Assessing financial capacity impairment in older adults. Generations. 2012;36:59–65. Retrieved from http://asaging.org/generations-journal-american-society-aging. [Google Scholar]

- Grisso T, Appelbaum PS. MacArthur competence assessment tool for treatment (MacCAT-T) Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press, Inc.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson SL, Hafemeister TL. APS investigation across four types of elder maltreatment. Journal of Adult Protection. 2012;14(2):82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kane M, Trochim WMK. Concept Mapping for Planning and Evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publication; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp BJ, Mosqueda LA. Elder financial abuse: An evaluation framework and supporting evidence. Journal of American Geriatric Society. 2005;53:1123–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw MM, Webber LS. Assessment of financial competence. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law. 2008;15:40–55. [Google Scholar]

- Laumann EO, Leitsch SA, Waite LJ. Elder mistreatment in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a nationally representative study. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2008;63(4):S248–S254. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.4.s248. Retrieved from http://psychsocgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtenberg PA, Stickney L, Paulson D. Is psychological vulnerability related to the experience of fraud in older adults? Clinical Gerontologist. 2013;36(2):132–146. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2012.749323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marson DC. Loss of financial competency in dementia: Conceptual and empirical approaches. Aging, Neuropsychology, and Cognition. 2001;8:164–181. [Google Scholar]

- Marson DC, Martin RC, Wadley V, Griffith HR, Snyder S, Goode PS, Harrell LE. Clinical interview assessment of financial capacity in older adults with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57(5):806–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02202.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mast BT. Whole person dementia assessment. Baltimore, MD: Health Professions Press, Inc.; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nerenberg L, Davies M, Navarro AE. In pursuit of a useful framework to champion elder justice. Generations. 2012;36:89–96. Retrieved from http://generations.metapress.com/content/b2755214766p275n/ [Google Scholar]

- Okonkwo O, et al. Awareness of functional difficulties in mild cognitive impairment: A multidomain assessment approach. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57:978–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02261.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsker DM, Pachana NA, Wilson J, Tilse C, Byrne GJ. Financial capacity in older adults: A review of clinical assessment approaches and considerations. Clinical Gerontologist. 2010;33:332–346. [Google Scholar]

- Sherod MG, Griffith HR, Copeland J, Belue K, Krzywanski S, Zamrini EY, et al. Neurocognitive predictors of financial capacity across the dementia spectrum: Normal aging, mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer's disease. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2009;15:258–267. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709090365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman KI, Cohen CA, Hull I. Psychiatric issues in retrospective challenges of testamentary capacity. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;20:63–69. doi: 10.1002/gps.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiegel LA. An overview of elder financial exploitation. Generations. 2012;36:73–80. Retrieved from http://generations.metapress.com/content/7523571065012268/ [Google Scholar]

- Teaster PB, Roberto KA, Migliaccio JN, Timmerman S, Blancato RB. Elder financial abuse in the news. Public Policy and Aging Report. 2012;22:33–36. Retrieved from http://www.geron.org/policy-center/policy-publications/public-policy-and-aging-report?start=1. [Google Scholar]

- Whitlatch CJ. Person-centered care in the early stages of dementia: Honoring individuals and their choices. Generations. 2013;37(3):30–36. [Google Scholar]