Abstract

The genome size of an organism varies from species to species. The C-value paradox enigma is a very complex puzzle with regards to vast diversity in genome sizes in eukaryotes. Here we reported the detailed genomic information of 172 fungal species among different fungal genomes and found that fungal genomes are very diverse in nature. In fungi, the diversity of genomes varies from 8.97 Mb to 177.57 Mb. The average genome sizes of Ascomycota and Basidiomycota fungi are 36.91 and 46.48 Mb respectively. But higher genome size is observed in Oomycota (74.85 Mb) species, a lineage of fungus-like eukaryotic microorganisms. The average coding genes of Oomycota species are almost doubled than that of Acomycota and Basidiomycota fungus.

Keywords: Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Chytridiomycota, Monoblepharidomycota, Neocallimastigomycota, Blastocladiomycota, Glomeromycota, Entomophthoromycota, Stramenopiles and micorsporidia

Introduction

Fungi are the larger group of eukaryotic organisms that ranges from yeast and slime molds to mushrooms. These organisms are majorly classified as monophyletic Eumycota group and their diversity ranges from 500 thousand to 9.9 million spanning over 1 billion years of evolutionary history [1,2]. They are abundant at worldwide scale due to their small size and their cryptic lifestyle in soil, dead and decomposing matter, as symbionts with algae, fungi, bryophyte, pteridophyte, higher plants and animals [3-7]. These organisms dominate earth from polar to temperate and tropical habitats [8-10]. Due to their ecological dominance, they play a central role in human endeavor. The fungus (mushroom and truffle) are directly used as human food and yeasts are used in bread industry. The fungi also carry out nutrient cycling by decomposing organic matter [11-13]. They also produce antibiotics, enzymes, mycotoxins, alkaloids, polyketides and other chemical compounds [14-21].

The kingdom fungi are classified into several major phyla namely Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Chytridiomycota, Monoblepharidomycota, Neocallimastigomycota, Blastocladiomycota, Glomeromycota, Entomophthoromycota, Stramenopiles and Micorsporidia and sub-phyla namely Kickxellomycotina, mucoromycotina and Zoopagomycotina [22,23]. The diverse ecological dominance of fungus makes them important from an evolutionary point of view. That is why fungi are subjected to intense phylogenetic, ecological and molecular studies. The advancement in high throughput sequencing technology progressed rapidly that led to sequencing of large numbers of fungal genomes. The evolution of biological diversity raises several questions such as how much variation can be expected among closely or related genomes. This can be answered by the comparing closely related genomes. So we carried out a global search of fungal genomes in MycoCosm and JGI database and studied the evolutionary relationships of their genome sizes and reported here [24-26].

Fungal genome size

Recently, the genome sequencing technology has emerged as one of the most efficient tools that can provide whole information of a genome in a small period of time. Since the completion of genome sequencing of the model fungus S. cerevisae in 1996, sequencing of large numbers of fungal genomes are now completed. Sequencing of large numbers of fungal genomes will allow us to understand the diversity of genes encoding enzymes, and pathways that produces several novel compounds [24]. Although the fungi are very diverse in nature, their basic cellular physiology and genetics shares some common components with plants and animal cells. These include multi-cellularity, cytoskeletal structures, cell cycle, circadian rhythm, intercellular signaling, sexual reproduction, development and differentiation [27]. It was previously thought that genomes of all fungi are derived from the genome of the model fungi Saccharomyces cerevisae [27]. However recent explosion in fungal genome sequencing greatly expanded the fungal genomics and molecular diversity of these organisms. Compared to the genome size of animals and plants, the genome sizes of fungi are small [28]. The genome size of model fungi S. cerevisae is bit more than 12 Mb (Table 1). From the studied 172 fungal species, only seven species have genome sizes larger than 100 Mb (Table 1). So, the probability of occurrence of larger genomes in fungi is very small. The genome size of Cenococcum geophilum (177.57 Mb) is the largest and the genome size of Hansenula polymorpha (8.97 Mb) is the smallest from the studied species. Both species belong to Ascomycota. In the group of Basidiomycota species, the genome size of Wallemia sebi (9.82 Mb) is the smallest one and genome of Dendrothele bispora (130.65) is the largest one (Table 1). No single species from Chytridiomycota, Glomeromycota, Oomycota, Stramenopiles, Mucoromycotina have genome size larger than 100 Mb. Although there is large variation in genome size in fungi, the average genome size of fungal species taken during this study is 42. 30 Mb (Table 1). The average genome sizes of fungal species belonging to different phyla are provided in Table 2. From the table we can observe that the average genome size of Ascomycota group of fungi is 36.91 Mb. The average genome size of Basidiomycota group is 46.48 Mb. The average genome size of Oomycota group of fungi is 74.85 Mb which is the highest among all groups (Table 2). If we consider about the coding gene sequence in fungi, in average the Acomycota, Basidiomycota, Oomycota and Mucoromycotina groups encodes for 11129.45, 15431.51, 24173.33, 13306 no. of genes respectively in their genomes (Table 2).

Table 1.

List of genome size (Mb), numbers of coding genes, and average numbers of exons present per fungal species from the different phyla of Kingdom Fungi

| Sl. No | Name of Fungal Species | Division | Genome Size Mbp | No. Of Contigs | No. Of Scaffolds | No of Gene Models | Average Exons Per Gene |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Acidomyces richmondensis | Ascomycota | 29.88 | 3164 | 3164 | 11202 | 2.28 |

| 2 | Acremonium alcalophilum | Ascomycota | 54.42 | 865 | 15 | 9491 | 4.05 |

| 3 | Agaricus bisporus | Basidiomycota | 30.2 | 254 | 29 | 10438 | 6.05 |

| 4 | Amanita muscaria Koide | Basidiomycota | 40.70 | 3814 | 1101 | 18153 | 4.54 |

| 5 | Amorphotheca resinae | Ascomycota | 28.63 | 261 | 32 | 9642 | 2.97 |

| 6 | Anthostoma avocetta | Ascomycota | 56.23 | 1038 | 786 | 15755 | 2.93 |

| 7 | Antrodia sinuosa | Basidiomycota | 30.17 | 1482 | 1387 | 11327 | 6.09 |

| 8 | Apiospora montagnei | Ascomycota | 47.67 | 706 | 686 | 16992 | 2.52 |

| 9 | Aplanochytrium kerguelense | Stramenopiles | 35.77 | 523 | 207 | 11892 | 2.75 |

| 10 | Aplosporella prunicola | Ascomycota | 32.82 | 763 | 334 | 12579 | 2.67 |

| 11 | Ascobolus immersus | Ascomycota | 59.53 | 1225 | 706 | 17877 | 2.67 |

| 12 | Ascoidea rubescens | Ascomycota | 17.50 | 101 | 63 | 6802 | 1.39 |

| 13 | Aspergillus acidus | Ascomycota | 37.47 | 318 | 107 | 13530 | 3.10 |

| 14 | Aspergillus niger | Ascomycota | 34.85 | 24 | 24 | 11910 | 3.38 |

| 15 | Atractiellales sp. | Basidiomycota | 51.47 | 3076 | 1998 | 17606 | 5.30 |

| 16 | Aulographum hederae | Ascomycota | 31.98 | 613 | 173 | 12127 | 2.66 |

| 17 | Aurantiochytrium limacinum | Stramenopiles | 60.93 | 1118 | 181 | 14859 | 1.45 |

| 18 | Aureobasidium pullulans | Ascomycota | 29.62 | 84 | 75 | 10809 | 2.51 |

| 19 | Auricularia subglabra | Basidiomycota | 76.85 | 2158 | 761 | 25459 | 4.80 |

| 20 | Babjeviella inositovora | Ascomycota | 15.22 | 210 | 49 | 6403 | 1.27 |

| 21 | Backusella circina | Mucoromycotina | 48.65 | 2354 | 1095 | 17039 | 4.25 |

| 22 | Baudoinia compniacensis | Ascomycota | 21.88 | 35 | 19 | 10513 | 2.14 |

| 23 | Bjerkandera adusta | Basidiomycota | 42.73 | 1263 | 508 | 15473 | 5.59 |

| 24 | Boletus edulis | Basidiomycota | 46.64 | 4723 | 1099 | 16933 | 4.88 |

| 25 | Botryobasidium botryosum | Basidiomycota | 46.67 | 1446 | 334 | 16526 | 5.58 |

| 26 | Calocera cornea | Basidiomycota | 33.24 | 1032 | 545 | 13177 | 4.44 |

| 27 | Calocera viscosa | Basidiomycota | 29.10 | 487 | 214 | 12378 | 4.59 |

| 28 | Candida caseinolytica | Ascomycota | 9.18 | 49 | 6 | 4657 | 1.20 |

| 29 | Catenaria anguillulae | Blastocladiomycota | 36.22 | 2577 | 801 | 14188 | 2.50 |

| 30 | Cenococcum geophilum | Ascomycota | 177.57 | 2893 | 268 | 27529 | 4.08 |

| 31 | Cercospora zeae-maydis | Ascomycota | 46.61 | 2555 | 917 | 12020 | 2.32 |

| 32 | Chalara longipes | Ascomycota | 52.43 | 175 | 54 | 19765 | 3.06 |

| 33 | Choiromyces venosus | Ascomycota | 126.04 | 3183 | 1176 | 17986 | 2.84 |

| 34 | Cochliobolus sativus | Ascomycota | 34.42 | 478 | 157 | 12250 | 2.63 |

| 35 | Coemansia reversa | Kickellomycotina | 21.84 | 1063 | 346 | 7347 | 1.51 |

| 36 | Conidiobolus coronatus | Entomophthoromycota | 39.90 | 7809 | 1050 | 10635 | 2.78 |

| 37 | Coniophora puteana | Basdiomycota | 42.97 | 1034 | 210 | 13761 | 6.11 |

| 38 | Coprinopsis cinerea | Basdiomycota | 37.5 | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| 39 | Cortinarius glaucopus | Basidiomycota | 63.45 | 2103 | 769 | 20377 | 5.05 |

| 40 | Cronartium quercuum | Basidiomycota | 76.57 | 10431 | 1198 | 13903 | 4.35 |

| 41 | Cryphonectria parasitica | Ascomycota | 43.9 | 33 | 26 | 11609 | 2.91 |

| 42 | Cryptococcus vishniacii | Basidiomycota | 19.69 | 137 | 50 | 7232 | 6.25 |

| 43 | Cucurbitaria berberidis | Ascomycota | 32.91 | 184 | 42 | 12439 | 2.71 |

| 44 | Cyberlindnera jadinii | Ascomycota | 13.02 | 392 | 76 | 6038 | 1.35 |

| 45 | Cylindrobasidium torrendii | Basidiomycota | 31.57 | 1222 | 1149 | 13940 | 5.17 |

| 46 | Dacryopinax sp. | Basidiomycota | 29.50 | 878 | 99 | 10242 | 4.83 |

| 47 | Daedalea quercina | Basidiomycota | 32.74 | 1025 | 357 | 12199 | 5.80 |

| 48 | Daldinia eschscholzii | Ascomycota | 37.55 | 512 | 398 | 11173 | 2.89 |

| 49 | Dekkera bruxellensis | Ascomycota | 13.37 | 1374 | 84 | 5600 | 1.44 |

| 50 | Dendrothele bispora | Basidiomycota | 130.65 | 6351 | 3942 | 33645 | 5.09 |

| 51 | Dichomitus squalens | Basidiomycota | 42.75 | 2852 | 542 | 12290 | 5.84 |

| 52 | Didymella exigua | Ascomycota | 34.39 | 1010 | 176 | 12394 | 2.46 |

| 53 | Dioszegia cryoxerica | Basidiomycota | 39.52 | 1318 | 865 | 15948 | 5.36 |

| 54 | Dissoconium aciculare | Ascomycota | 26.54 | 232 | 54 | 10299 | 2.17 |

| 55 | Dothidotthia symphoricarpi | Ascomycota | 34.43 | 268 | 59 | 11790 | 2.71 |

| 56 | Eurotium rubrum | Ascomycota | 26.21 | 371 | 110 | 10076 | 3.07 |

| 57 | Exidia glandulosa | Basidiomycota | 78.17 | 4024 | 1727 | 26765 | 4.83 |

| 58 | Exobasidium vaccinii | Basidiomycota | 16.99 | 246 | 119 | 7453 | 2.79 |

| 59 | Fibulorhizoctonia sp. | Basidiomycota | 95.13 | 3901 | 1918 | 32946 | 4.63 |

| 60 | Fomitiporia mediterranea | Basidiomycota | 63.35 | 5766 | 1412 | 11333 | 6.06 |

| 61 | Fomitopsis pinicola | Basidiomycota | 46.30 | 988 | 504 | 13885 | 5.56 |

| 62 | Galerina marginata | Basidiomycota | 59.42 | 1272 | 414 | 21461 | 5.30 |

| 63 | Ganoderma sp. | Basidiomycota | 39.52 | 503 | 156 | 12910 | 5.82 |

| 64 | Gloeophyllum trabeum | Basidiomycota | 37.18 | 2289 | 443 | 11846 | 6.14 |

| 65 | Glomerella acutata | Ascomycota | 50.04 | 378 | 307 | 15777 | 2.83 |

| 66 | Glomerella cingulata | Ascomycota | 58.84 | 774 | 119 | 18975 | 2.79 |

| 67 | Gonapodya prolifera | Monoblepharidomycetes | 48.79 | 1154 | 352 | 13902 | 5.58 |

| 68 | Gymnascella aurantiaca | Ascomycota | 25.35 | 356 | 347 | 9106 | 3.12 |

| 69 | Gymnascella citrina | Ascomycota | 25.16 | 305 | 272 | 9779 | 2.99 |

| 70 | Gyrodon lividus | Basidiomycota | 43.05 | 1390 | 369 | 11779 | 5.75 |

| 71 | Hanseniaspora valbyensis | Ascomycota | 11.46 | 1163 | 646 | 4800 | 1.20 |

| 72 | Hansenula polymorpha | Ascomycota | 8.97 | 9 | 7 | 5177 | 1.20 |

| 73 | Hebeloma cylindrosporum | Basidiomycota | 37.61 | 222 | 222 | 16841 | 5.05 |

| 74 | Heterobasidion annosum | Basidiomycota | 33.7 | 18 | 15 | 13405 | 5.54 |

| 75 | Hydnomerulius pinastri | Basidiomycota | 38.28 | 2315 | 603 | 13270 | 5.84 |

| 76 | Hypholoma sublateritium | Basidiomycota | 48.03 | 1329 | 704 | 17911 | 5.29 |

| 77 | Hyphopichia burtonii | Ascomycota | 12.40 | 105 | 27 | 6002 | 1.22 |

| 78 | Hypoxylon sp. | Ascomycota | 46.59 | 580 | 505 | 12256 | 2.90 |

| 79 | Jaapia argillacea | Basidiomycota | 45.05 | 1182 | 295 | 5.53 | 5.53 |

| 80 | Laccaria amethystina | Basidiomycota | 52.20 | 4756 | 1299 | 21066 | 4.49 |

| 81 | Laccaria bicolor | Basidiomycota | 60.71 | 584 | 55 | 23132 | 5.28 |

| 82 | Laetiporus sulphureus | Basidiomycota | 39.92 | 1207 | 403 | 13774 | 5.72 |

| 83 | Lentinus tigrinus | Basidiomycota | 39.68 | 571 | 286 | 15581 | 5.59 |

| 84 | Leucogyrophana mollusca | Basidiomycota | 35.19 | 1347 | 1262 | 14619 | 5.89 |

| 85 | Lichtheimia hyalospora | Mucoromycotina | 33.28 | 2294 | 2222 | 12062 | 4.99 |

| 86 | Lipomyces starkeyi | Ascomycota | 21.27 | 439 | 117 | 8192 | 2.85 |

| 87 | Lophiostoma macrostomum | Ascomycota | 42.58 | 1294 | 1282 | 16160 | 2.74 |

| 88 | Macrolepiota fuliginosa | Basidiomycota | 46.40 | 4852 | 3478 | 15801 | 5.39 |

| 89 | Melampsora laricis-populina | Basidiomycota | 101.1 | --- | 462 | 19694 | --- |

| 90 | Melanconium sp. | Ascomycota | 58.52 | 465 | 100 | 16656 | 2.68 |

| 91 | Melanomma pulvis-pyrius | Ascomycota | 42.09 | 1771 | 1754 | 15881 | 2.77 |

| 92 | Meliniomyces bicolor | Basidiomycota | 82.38 | 301 | 206 | 18619 | 2.96 |

| 93 | Metschnikowia bicuspidata | Ascomycota | 16.06 | 421 | 48 | 5851 | 1.27 |

| 94 | Mixia osmundae | Basidiomycota | 13.63 | 204 | 156 | 6903 | 4.54 |

| 95 | Monascus purpureus | Ascomycota | 23.44 | 319 | 296 | 8918 | 3.19 |

| 96 | Monascus ruber | Ascomycota | 24.80 | 362 | 320 | 9650 | 3.13 |

| 97 | Mortierella elongata | Mucoromycotina | 49.96 | 3314 | 473 | 14964 | 3.47 |

| 98 | Mucor circinelloides | Mucoromycotina | 36.6 | 26 | 26 | 11719 | 3.8 |

| 99 | Myceliophthora thermophila | Ascomycota | 38.74 | 7 | 7 | 9110 | 2.83 |

| 100 | Mycosphaerella graminicola | Ascomycota | 39.7 | --- | 129 | 10952 | --- |

| 101 | Myriangium duriaei | Ascomycota | 25.69 | 32 | 16 | 10685 | 2.37 |

| 102 | Nadsonia fulvescens | Ascomycota | 13.75 | 64 | 20 | 5657 | 1.57 |

| 103 | Neolentinus lepideus | Basidiomycota | 35.64 | 1215 | 331 | 13164 | 5.71 |

| 104 | Neurospora discreta | Ascomycota | 37.3 | --- | 176 | 9948 | --- |

| 105 | Neurospora tetrasperma | Ascomycota | 37.8 | 542 | 155 | 10640 | 2.72 |

| 106 | Oidiodendron maius | Ascomycota | 46.43 | 387 | 100 | 16703 | 2.97 |

| 107 | Pachysolen tannophilus | Ascomycota | 12.60 | 583 | 198 | 5675 | 1.33 |

| 108 | Patellaria atrata | Ascomycota | 28.69 | 501 | 127 | 9794 | 2.97 |

| 109 | Paxillus rubicundulus | Basidiomycota | 53.01 | 7170 | 6945 | 22065 | 3.81 |

| 110 | Penicillium brevicompactum | Ascomycota | 32.11 | 96 | 35 | 11536 | 3.09 |

| 111 | Penicillium canescens | Ascomycota | 33.26 | 248 | 62 | 12374 | 3.12 |

| 112 | Penicillium janthinellum | Ascomycota | 35.15 | 273 | 94 | 12098 | 3.07 |

| 113 | Penicillium raistrickii | Ascomycota | 31.44 | 104 | 76 | 11368 | 3.11 |

| 114 | Phlebia brevispora | Basidiomycota | 49.96 | 3178 | 1645 | 16170 | 5.66 |

| 115 | Phlebiopsis gigantea | Basidiomycota | 30.14 | 1195 | 573 | 11891 | 6.00 |

| 116 | Phycomyces blakesleeanus | Mucoromycotina | 53.9 | 350 | 80 | 16528 | 4.5 |

| 117 | Phytophthora capsici | Oomycota | 64 | 10760 | 917 | 19805 | 2.20 |

| 118 | Phytophthora cinnamomi | Oomycota | 77.97 | 9537 | 1314 | 26131 | 2.10 |

| 119 | Phytophthora sojae | Oomycota | 82.60 | 1643 | 83 | 26584 | 2.39 |

| 120 | Pichia stipitis | Ascomycota | 15.4 | --- | 394 | 5841 | ~1 |

| 121 | Piedraia hortae | Ascomycota | 16.95 | 214 | 132 | 7572 | 1.84 |

| 122 | Piloderma croceum | Basidiomycota | 59.33 | 4469 | 715 | 21583 | 4.75 |

| 123 | Piromyces sp. | Neocallimastigomycota | 71.02 | 17217 | 1656 | 14648 | 3.09 |

| 124 | Pisolithus microcarpus | Basidiomycota | 53.03 | 5476 | 1064 | 21064 | 4.04 |

| 125 | Pleomassaria siparia | Ascomycota | 43.18 | 1023 | 193 | 13486 | 2.81 |

| 126 | Pleurotus ostreatus | Basidiomycota | 35.6 | 3272 | 572 | 11603 | 6.1 |

| 127 | Polychaeton citri | Ascomycota | 27.21 | 451 | 416 | 10582 | 2.12 |

| 128 | Polyporus arcularius | Basidiomycota | 43.45 | 2601 | 2540 | 17525 | 5.27 |

| 129 | Punctularia strigosozonata | Basidiomycota | 34.17 | 1327 | 195 | 11538 | 6.23 |

| 130 | Pycnoporus sanguineus | Basidiomycota | 36.04 | 2046 | 657 | 14165 | 5.59 |

| 131 | Ramaria rubella | Basidiomycota | 105.46 | 5927 | 1553 | 19287 | 5.53 |

| 132 | Rhizophagus irregularis | Glomeromycota | 91.08 | 28405 | 28371 | 30282 | 3.46 |

| 133 | Rhizopus microsporus | Mucoromycotina | 25.97 | 823 | 131 | 10905 | 4.03 |

| 134 | Rhodotorula graminis | Basidiomycota | 21.01 | 620 | 26 | 7283 | 6.24 |

| 135 | Rickenella mellea | Basidiomycota | 46.03 | 1236 | 1092 | 18952 | 4.98 |

| 136 | Saccharata proteae | Ascomycota | 31.43 | 727 | 245 | 9234 | 3.08 |

| 137 | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Ascomycota | 12.07 | 16 | 16 | 6575 | 1.04 |

| 138 | Saitoella complicata | Ascomycota | 14.14 | 35 | 35 | 7034 | 2.23 |

| 139 | Schizophyllum commune Loenen D | Basidiomycota | 35.88 | 1822 | 1774 | 13827 | 5.55 |

| 140 | Schizophyllum commune Tattone D | Basidiomycota | 36.46 | 1757 | 1707 | 15199 | 5.27 |

| 141 | Schizopora paradoxa | Basidiomycota | 44.41 | 1342 | 1291 | 17098 | 5.78 |

| 142 | Scleroderma citrinum | Basidiomycota | 56.14 | 3919 | 938 | 21012 | 4.33 |

| 143 | Sebacina vermifera | Basidiomycota | 38.09 | 2457 | 546 | 15312 | 4.94 |

| 144 | Septoria musiva | Ascomycota | 29.35 | 706 | 72 | 10233 | 2.44 |

| 145 | Serpula lacrymans | Basidiomycota | 42.73 | 375 | 36 | 12789 | 5.73 |

| 146 | Sistotremastrum niveocremeum | Basidiomycota | 35.36 | 699 | 179 | 13080 | 5.95 |

| 147 | Sodiomyces alkalinus | Ascomycota | 43.45 | 290 | 25 | 9411 | 3.32 |

| 148 | Spathaspora passalidarum | Ascomycota | 13.2 | 26 | 8 | 5983 | 1.2 |

| 149 | Sporobolomyces roseus | Basidiomycota | 21.2 | --- | 76 | 5536 | --- |

| 150 | Sporormia fimetaria | Ascomycota | 25.89 | 293 | 140 | 10783 | 2.70 |

| 151 | Stereum hirsutum | Basidiomycota | 46.51 | 995 | 159 | 14072 | 6.52 |

| 152 | Suillus brevipes | Basidiomycota | 51.71 | 4139 | 1550 | 22453 | 4.54 |

| 153 | Talaromyces aculeatus | Ascomycota | 37.27 | 165 | 49 | 13793 | 3.16 |

| 154 | Terfezia boudieri | Ascomycota | 63.23 | 2078 | 516 | 10200 | 3.61 |

| 155 | Thermoascus aurantiacus | Ascomycota | 28.49 | 196 | 48 | 8798 | 3.33 |

| 156 | Thielavia appendiculata | Ascomycota | 32.74 | 501 | 109 | 11942 | 2.77 |

| 157 | Thielavia arenaria | Ascomycota | 30.99 | 354 | 69 | 10954 | 2.80 |

| 158 | Thielavia hyrcaniae | Ascomycota | 31.18 | 972 | 251 | 11338 | 2.73 |

| 159 | Trametes versicolor | Basidiomycota | 44.79 | 1443 | 283 | 14296 | 5.81 |

| 160 | Trichaptum abietinum | Basiodiomycota | 40.61 | 1345 | 492 | 14978 | 5.65 |

| 161 | Trichoderma citrinoviride | Ascomycota | 33.48 | 699 | 533 | 9737 | 3.10 |

| 162 | Trypethelium eluteriae | Ascomycota | 32.16 | 747 | 730 | 11858 | 2.83 |

| 163 | Tulasnella calospora | Basidiomycota | 62.39 | 6848 | 1335 | 19659 | 4.65 |

| 164 | Umbelopsis ramanniana | Mucoromycotina | 23.08 | 239 | 198 | 9931 | 4.75 |

| 165 | Wallemia sebi | Basidiomycota | 9.82 | 114 | 56 | 5284 | 4.03 |

| 166 | Wickerhamomyces anomalus | Ascomycota | 14.15 | 207 | 46 | 6423 | 1.42 |

| 167 | Wilcoxina mikolae | Ascomycota | 117.29 | 5591 | 1604 | 13093 | 3.24 |

| 168 | Wolfiporia cocos | Basidiomycota | 50.48 | 2228 | 348 | 12746 | 6.31 |

| 169 | Xanthoria parietina | Ascomycota | 31.90 | 302 | 39 | 10818 | 2.98 |

| 170 | Xylona heveae | Ascomycota | 24.34 | 56 | 27 | 8205 | 3.41 |

| 171 | Zasmidium cellare | Ascomycota | 38.25 | 365 | 267 | 16015 | 2.50 |

| 172 | Zopfia rhizophila | Ascomycota | 152.78 | 1349 | 864 | 21730 | 2.77 |

| Average | 42.300 | 13437.21 | 3.79 |

Table 2.

Average genome size, and average number of coding genes and exons present in the different phyla/sub-phyla of the Kingdom Fungi

| Fungal division | Average Genome Size (Mb) | Average No. Of Genes | Average No. Of Exons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ascomycota | 36.91 | 11129.45 | 2.58 |

| Basidiomycota | 46.48 | 15431.51 | 5.28 |

| Oomycota | 74.85 | 24173.33 | 2.23 |

| Mucoromycotina | 38.777 | 13306.85 | 4.25 |

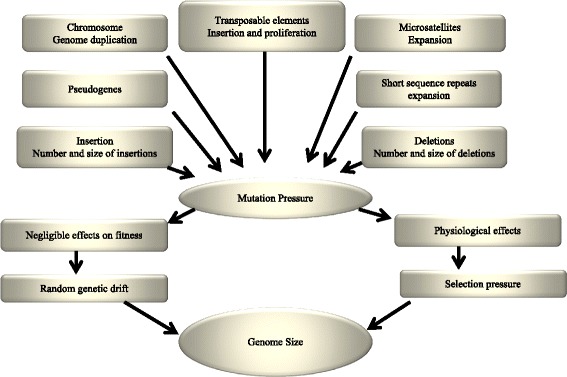

The comparative analysis of fungal genomes show fungi are very divergent [27]. It was earlier thought that genomes of Magnaporthe grisea and Neurospora crassa share a common ancestor. But, comparative genomes analyses revealed only 47% amino acid sequence identity and absence of conserved synteny [27]. Only few genes are identified to be in conserved co-linearity. This shows that even members of the same genus can show remarkable divergence at the genomic level. A genomic comparison between Aspergillus nidulans, Aspergillus fumigatus and Aspergillus oryzae shows only 68% of amino acid sequence identity [27]. The genome duplication and translocation have major impact in evolution in yeast (Figure 1) [29,30]. The whole genome duplication in yeast followed by massive gene loss is confirmed by comparative experimental analysis [31,32]. This indicates that fungal genomes are very dynamic in nature. Lavergne et al. [33] reported that genome size reduction can trigger rapid phenotypic evolution in invasive plants. Their report suggests that the invasive genotypes had smaller genomes. Smaller genome sizes have phenotypic effects that increased the invasive potential [33]. But in exception, for example, the duckweeds which are smallest, fast-growing and simplest flowering plants are invasive in nature and contains increased DNA content in their genomes [34].

Figure 1.

Role of different forces affecting the evolution of genome size. The major important factors are transposable elements (TEs), short sequence repeats, microsatellites, genome duplication and others. The mutational and selection pressure plays a significant role in this process. The negligible selective effects governed by genetic drift also contribute for the evolution of genome size. Overall all the forces play a role towards the increase in genome size at different levels. The photograph is adapted according to the report of Petrov [37].

Evolution in genome size

Genomes are aggregates of genes and this concept nicely fits with the prokaryotic organisms and viruses [35]. This concept is very inappropriate for eukaryotic organisms as most of the eukaryotic genomes are studded with nongenic and unconstrained repetitive DNA. This can lead to approximately 200,000 fold variation in genome size [36]. The genome size of an organism depends on the particular developmental and ecological need of the organism [37]. The genes are made up of DNA and it is a general assumption that more complex organisms requires more genes and thus contain more DNA in its genomes. The simple organisms probably contain fewer essential genes compared to more complex organisms and thus contain less DNA in its genomes. However this observation is not true. Some very simple organisms could have more DNA content than complex multi-cellular organisms. For example, some amoeba species have 200 times more DNA than humans [38]. Similarly, lilies have 200 times more DNA than that of rice [39]. But in many organisms much of the DNA content is noncoding and repetitive. But it is very important to understand which evolutionary forces produces enormous amount of noncoding DNA? What are the adaptive functions of these nongenic DNA? If these nongenic DNA don’t have any essential adaptive roles, than why natural selection favors the burden of synthesis of extra DNA? Several hypotheses are postulated since long days to address these questions. But still there is debate over it. Some of the hypotheses are discussed later. From the studied fungal genomes, the average genome sizes of Oomycota species (74.85 Mb) are higher than other. The Ascomycota and Mucoromycotina species shares more or less than same average genome size i.e. 36.91 and 37.02 Mb, respectively. In contrary, the average genome sizes of Basidiomycota species is 46.48 Mbs. The increase in genome size in Oomycota species is also directly correlated with the increase in the numbers of average coding gene sequences. The average numbers of coding genes present in Oomycota species are 24173.33 genes per genome which is almost the double number present in Ascomycota and Basidiomycota species.

The adaptive theories of genome evolution

If certain numbers of genes are responsible for the phenotype and genotypic characters of an organism, why there are extra amounts of DNA in its genome? The adaptive theory explains that this extra DNA abundance is for adaptive function and its content don’t have any significant effects in phenotype of the organism [40]. A large genome directly increases the nuclear and cellular volumes [41]. This largely helps to buffer the fluctuation in the concentration of regulatory proteins or protect coding DNA from spontaneous mutation [42]. So the variation in the genome size is due to adaptive needs or due to natural selection in different organisms [37].

Junk DNA theory of genome evolution

The junk DNA hypothesis suggests that these extra DNAs are useless, maladaptive DNAs and fixed by random drift [43]. These DNAs are carried in chromosome and don’t have any significant role in the phenotype of an organism [43]. These junk DNAs are known as parasitic DNA or transposable elements (TEs) [44]. The mutational mechanisms of DNA gain or loss can lead to minor changes in the genome of an organism, but changes in genome size may occur by the involvement of different evolutionary forces [37]. An increase in transposition rate certainly can lead to an increase in genome size [37]. Instead of thinking in genome size evolution by adaptive evolution theory or by junk DNA theory, it is very important to understand which evolutionary force is responsible for changes in genome size. The mutational and selective forces might have vast potential to affect the change in genome sizes (Figure 1) [37]. If we can get the specific clue, we can try to estimate the strength of individual force and whether the magnitude of individual force may produce changes in genome sizes. This approach can explain the quantitative sense about genetic mechanism and the selective forces that affect the genome size.

The activities of transposable elements are very fast and can able to amplify the a transposable copy number into 20-100 copies (~0.1-1 Mbp) in a single generation [45,46]. The changes in genome size through spontaneous deletion or insertion are relatively slow [47]. For example, the Drosophila melanogaster genome losses less than a single base pair per generation [47]. If there is strong selection in increasing in gnome sizes, strong mutational pressure also can not affect the evolution of genome size [37]. However, strong selection for increase in genome size can substantially slow down the impact of mutation rate. If we can get the information of time scale of genome size divergence, then we can infer the genome-size changes between two closely related organisms. If we will consider the evolutionary development of fungus, Ascomycota has higher evolutionary rate than Basidiomycota [48]. But when we compared the average genome size of Ascomycota, Basidiomycota and Mucoromycotina, we found that the genome size of Basidiomycota is larger than the genome size of Ascomycota and Mucoromycotina. This may suggests that the evolution of fungal genome size is due to addition of nucleotides/DNA contents rather than deletion of nucleotides.

Some forces act on the traits correlated with total genome size of an organism [37]. In this case, natural selection forces affect only to few genomic components. For example, the increase in rate of heterochromatin shrinkage through heterochromatic DNA should not affect the size of euchromatin [37]. Similarly, the expansion in satellite DNA should not hamper the size of satellite free sequences. Another important question is that, whether different genomic components are varying together in a correlated fashion during evolution of genome size? Although there are no significant current evidences regarding this question, there are certain cytogenetic and molecular studies available. The cytogenetic study revealed that genome size differences are scattered throughout the euchromatic portion of the genome [49-52]. Comparison of orthologous introns revealed correlation between average size of intron and genome size [53]. The changes in the intron length do not account for the changes in the genome size. Although transposable elements are largely associated with the increase in genome size, presence of increased simple repeated sequences, pseudogenes, increased size of inter-enhancer spacers and microsatellites are also associated with increase in genome size (Figure 1) [54-56]. When there are changes in genome size, they do it across all the genomic components. This suggests that a global force acts as the direct agent for change in genome size. So, from our study we can speculate that Oomycota species might harbors high densities of TEs, simple repeat sequences, microsatellites and pseudogenes. Similarly, the Basidiomycota species might have more densities of TEs, simple repeat sequences, microsatellites and pseudogenes compared to Ascomycota and other groups. Whitney et al. [57] reported about the nonadaptive process in plant genome size evolution. They hypothesized that genome expansion is maladaptive and lineages with small effective population size evolve larger genomes than those with large population size. In addition, mating systems are likely to affect genome size evolution via population size and spread of transposable elements [57].

Conclusion

The question of genome size (C-value paradox) is very puzzling. Most probably we can better understand about the evolution of fungal genome size by completely understanding the roles of noncoding DNAs. It is also equally important to understand whether the addition and deletion of additional DNA content varies between species to species and at organism level too. Although experimental approach like cytogenetic study of euchromatic region can give some lime light about this issue, still high fidelity experimental approaches are lacking till to date.

Acknowledgement

This work was carried out with the support of the Next-Generation Biogreen 21 Program (PJ011113), Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

TKM: collected all the relevant publications, surveyed the fungal genome, arranged the general structure of review, and drafted the manuscript and figure. HB: given permission for publication. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Tapan Kumar Mohanta, Email: nostoc.tapan@gmail.com.

Hanhong Bae, Email: hanhongbae@ynu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Hawksworth D. The magnitude of fungal diversity: the 1·5 million species estimate revisited. Mycol Res. 2001;105:1422–32. doi: 10.1017/S0953756201004725. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Touchon M, Hoede C, Tenaillon O, Barbe V, Baeriswyl S, Bidet P, et al. Organised genome dynamics in the Escherichia coli species results in highly diverse adaptive paths. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000344. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Das M, Royer TV, Leff LG. Diversity of fungi, bacteria, and actinomycetes on leaves decomposing in a stream. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:756–67. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01170-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perotto S, Actis-Perino E, Perugini J, Bonfante P. Molecular diversity of fungi from ericoid mycorrhizal roots. Mol Ecol. 1996;5:123–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.1996.tb00298.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson IC, Campbell CD, Prosser JI. Diversity of fungi in organic soils under a moorland – Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) gradient. Environ Microbiol. 2003;5:1121–32. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schardl CL, Leuchtmann A, Spiering MJ. Symbioses of grasses with seedborne fungal endophytes. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2004;55:315–40. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohanta TK, Bae H. Functional Genomics and Signaling Events in Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. J Plant Interact. 2015;10:21–40. doi: 10.1080/17429145.2015.1005180. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lau MCY, Jurgens JA, Farrell RL. Correction for pointing et al., highly specialized microbial diversity in hyper-arid polar desert. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2009;107:1254–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908274106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma L, Catranis CM, Starmer WT, Rogers SO. Revival and characterization of fungi from ancient polar ice. Mycologist. 1999;13:70–3. doi: 10.1016/S0269-915X(99)80012-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arnold AE, Maynard Z, Gilbert GS, Coley PD, Kursar TA. Are tropical fungal endophytes hyperdiverse? Ecol Lett. 2000;3:267–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2000.00159.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ingham RE, Trofymow JA, Ingham ER, Coleman DC. Interactions of bacteria, fungi, and their nematode grazers: effects on nutrient cycling and plant growth. Ecol Monogr. 1985;55:119–40. doi: 10.2307/1942528. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuste JC, Peñuelas J, Estiarte M, Garcia-Mas J, Mattana S, Ogaya R, et al. Drought-resistant fungi control soil organic matter decomposition and its response to temperature. Glob Chang Biol. 2011;17:1475–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02300.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rineau F, Roth D, Shah F, Smits M, Johansson T, Canbäck B, et al. The ectomycorrhizal fungus Paxillus involutus converts organic matter in plant litter using a trimmed brown-rot mechanism involving Fenton chemistry. Environ Microbiol. 2012;14:1477–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02736.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barke J, Seipke RF, Grüschow S, Heavens D, Drou N, Bibb MJ, et al. A mixed community of actinomycetes produce multiple antibiotics for the fungus farming ant Acromyrmex octospinosus. BMC Biol. 2010;8:109. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whitt J, Shipley SM, Newman DJ, Zuck KM. Tetramic acid analogues produced by co-culture of Saccharopolyspora erythraea with Fusarium pallidoroseum. J Nat Prod. 2014;77:173–7. doi: 10.1021/np400761g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demain A. Valuable secondary metabolites from fungi. In: Martín J-F, García-Estrada C, Zeilinger S, editors. Biosynth Mol Genet Fungal Second Metab SE - 1. New York: Springer; 2014. pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montoya S, Sánchez Ó, Levin L: Mathematical Modeling of Lignocellulolytic Enzyme Production from Three Species of White Rot Fungi by Solid-State Fermentation. In Adv Comput Biol SE - 52. Volume 232. Edited by Castillo LF, Cristancho M, Isaza G, Pinzón A, Rodríguez JMC. Springer International Publishing; 2014:371–377.

- 18.Anasonye F, Winquist E, Kluczek-Turpeinen B, Räsänen M, Salonen K, Steffen KT, et al. Fungal enzyme production and biodegradation of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxins and dibenzofurans in contaminated sawmill soil. Chemosphere. 2014;110:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.03.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nazari L, Pattori E, Terzi V, Morcia C, Rossi V. Influence of temperature on infection, growth, and mycotoxin production by Fusarium langsethiae and F. sporotrichioides in durum wheat. Food Microbiol. 2014;39:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kumara PM, Soujanya KN, Ravikanth G, Vasudeva R, Ganeshaiah KN, Shaanker RU. Rohitukine, a chromone alkaloid and a precursor of flavopiridol, is produced by endophytic fungi isolated from Dysoxylum binectariferum Hook.f and Amoora rohituka (Roxb). Wight &. Arn Phytomedicine. 2014;21:541–6. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2013.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agarwal V, Moore BS. Fungal polyketide engineering comes of age. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2014;111(34):12278–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1412946111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hibbett D, et al. A higher level phylogenetic classification of the fungi. Mycol Res. 2007;111:509–47. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Humber RA. A new phylum and reclassification for entomophthoroid fungi. Mycotaxon. 2012;120:477–92. doi: 10.5248/120.477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grigoriev IV, Nikitin R, Haridas S, Kuo A, Ohm R, Otillar R, et al. MycoCosm portal: gearing up for 1000 fungal genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D699–704. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nordberg H, Cantor M, Dusheyko S, Hua S, Poliakov A, Shabalov I, et al. The genome portal of the Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute: 2014 updates. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D26–31. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grigoriev IV, Cullen D, Goodwin SB, Hibbett D, Jeffries TW, Kubicek CP, et al. Fungal Biology Fueling the future with fungal genomics. Mycology. 2011;2:192–209. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galagan JE, Henn MR, Ma L-J, Cuomo C, Birren B. Genomics of the fungal kingdom: insights into eukaryotic biology. Genome Res. 2005;15:1620–31. doi: 10.1101/gr.3767105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tunlid A, Talbot NJ. Genomics of parasitic and symbiotic fungi. Genomics. 2002;5:513–9. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(02)00355-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dunham MJ, Badrane H, Ferea T, Adams J, Brown PO, Rosenzweig F, et al. Characteristic genome rearrangements in experimental evolution of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16144–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242624799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koszul R, Caburet S, Dujon B, Fischer G. Eucaryotic genome evolution through the spontaneous duplication of large chromosomal segments. EMBO J. 2004;23:234–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dujon B, Sherman D, Fischer G, Durrens P, Casaregola S, Lafontaine I, et al. Genome evolution in yeasts. Nature. 2004;430:35–44. doi: 10.1038/nature02579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kellis M, Birren BW, Lander ES. Proof and evolutionary analysis of ancient genome duplication in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature. 2004;428:617–24. doi: 10.1038/nature02424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lavergne S, Muenke NJ, Molofsky J. Genome size reduction can trigger rapid phenotypic evolution in invasive plants. Ann Bot. 2010;105:109–16. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcp271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang W, Kerstetter R, Michael TP. Evolution of genome size in duckweeds (Lemnaceae) J Bot. 2011;2011:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2011/570319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petrov D. Mutational equilibrium model of genome size evolution. Theor Popul Biol. 2002;61:531–44. doi: 10.1006/tpbi.2002.1605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gregory TR, Hebert PDN. The modulation of DNA content: proximate causes and ultimate consequences. Genome Res. 1999;9:317–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petrov D. Evolution of genome size: new approaches to an old problem. Trends Genet. 2001;17:23–8. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas C. The genetic organization of chromosomes. Annu Rev Genet. 1971;5:237–56. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.05.120171.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sahin A, Kaauwen MV, Esselink D, Bargsten JW, Tuyl JM, Visser RG, et al. Generation and analysis of expressed sequence tags in the extreme large genomes Lilium and Tulipa. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:640. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oslon-Manning CF, Wagner MR, Mitchell-Olds T. Adaptive evolution: evaluating empirical support for theoretical prediction. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;13:867–77. doi: 10.1038/nrg3322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cavalier-Smith T. Nuclear volume control by nucleoskeletal DNA, seletion for cell volume and cell growth rate, and the solution of the DNA C-value Paradox. J Cell Sci. 1978;34:247–78. doi: 10.1242/jcs.34.1.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vinogradov A. Buffering : a possible passive-homeostasis role for redundant DNA. J Theor Biol. 1998;193:197–9. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1997.0629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohno S. So much “junk” DNA in our genome. Brookhaven Symp Biol. 1972;23:366–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Orgel L, Crick F. Selfish DNA: the ultimate parasite. Nature. 1980;284:604–7. doi: 10.1038/284604a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Petrov DA, Schutzman JL, Hartl DL, Lozovskaya ER. Diverse transposable elements are mobilized in hybrid dysgenesis in Drosophila virilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1995;92:8050–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.8050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kalendar R, Tanskanen J, Immonen S, Nevo E, Schulman a H. Genome evolution of wild barley (Hordeum spontaneum) by BARE-1 retrotransposon dynamics in response to sharp microclimatic divergence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6603–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.110587497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petrov D, Hartl D. High rate of DNA loss in the Drosophila melanogaster and Drosophila virilis species groups. Mol Biol Evol. 1998;15:293–302. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang H, Guo S, Huang M, Thorsten L, Wei J. Ascomycota has a faster evolutionary rate and higher species diversity than Basidiomycota. Sci China Life Sci. 2010;53:1163–9. doi: 10.1007/s11427-010-4063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keyl H. A demonstrable local and geometric increase in the chromosomal DNA of Chironomus. Experientia. 1965;21:191–3. doi: 10.1007/BF02141878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Labani RM, Elkington TT. Nuclear DNA variation in the genus Allium L. (Liliaceae) Heredity (Edinb) 1987;59:119–28. doi: 10.1038/hdy.1987.103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ohri D. Genome size variation and plant systematics. Ann Bot. 1998;82:75–83. doi: 10.1006/anbo.1998.0765. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ohri D, Fritsch RM, Hanelt P. Systemafics and plam evolution of genome size in Allium (Alliaceae) Plant Syst Evol. 1998;210:57–86. doi: 10.1007/BF00984728. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moriyama EN, Petrov DA, Hartl DL. Letter to the editor genome size and intron size in Drosophila. Mol Biol Evol. 1998;15:770–3. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crollius HR. Characterization and repeat analysis of the compact genome of the freshwater pufferfish Tetraodon nigroviridis. Genome Res. 2000;10:939–49. doi: 10.1101/gr.10.7.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wessler SR. Transposable elements and the evolution of eukaryotic genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17600–1. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607612103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ellegren H. Microsatellites: simple sequences with complex evolution. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:435–45. doi: 10.1038/nrg1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Whitney KD, Baack EJ, Hamrick JL, Godt MW, Barringer BC, Bennet MD, et al. A role for nonadaptive process in plant genome size evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;64:2097–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.00967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]