Abstract

Background

The US is in an unprecedented era of health care reform that is pushing medical professionals and medical educators to evaluate the future of their patients, careers, and the field of medicine.

Objectives

To describe physician familiarity and knowledge with the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), and to determine if knowledge is associated with support and endorsement of the ACA.

Methods

Cross-sectional internet-based survey of 559 physicians practicing in California. Primary outcomes were physician support and endorsement of ACA: 1) overall impact on the country (1 item), and 2) perceived impact on physician’s medical practice (1 item). The primary predictor was knowledge of the ACA as measured with 10 questions. Other measures included age, gender, race-ethnicity, specialty, political views, provision of direct care, satisfaction with the practice of medicine, and compensation type. Descriptive statistics and multiple variable regression models were calculated.

Results

Respondents were 65% females, and the mean age was 54 years (+/− 9.7). Seventy-seven percent of physicians understood the ACA somewhat well/very well, and 59% endorsed the ACA, but 36% of physicians believed that health care reform will most likely hurt their practice. Primary care physicians were more likely to perceive that the new law will help their practice, compared to procedural specialties. Satisfaction with the practice of medicine, political affiliation, compensation type, and more knowledge of the health care law were independently associated with endorsement of the ACA.

Conclusions

Endorsement of the ACA varied by specialty, knowledge, and satisfaction with the practice of medicine.

Keywords: health policy, health reform, workforce, primary care

INTRODUCTION

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) is the most significant reform of the United States health care system in the past two decades, likely to change cost, access, and the quality of care for millions of Americans.1 Early results show that approximately 20 million Americans have gained coverage under the ACA. Among these individuals, 8 million enrolled in health insurance under the new health insurance exchanges created by this significant piece of legislation.2 The legislation is complex and expansive making it difficult for even the most experienced health care policy makers to predict its effects. To best serve their patients, physicians must be well informed of these coming changes and understand how they will impact their care and practice.

Previous studies have found familiarity with the ACA among the general public and physicians alike correlates with acceptance and approval or favorable endorsement of the ACA.3,4 Although the data is scant to date in the peer-reviewed literature, one study found a strong correlation between physician specialty, political affiliation and physician reactions to health care reform legislation.5,6 Another recently published study by David Rocke et al. described otolaryngology physician knowledge of the ACA which proved only slightly better than the general public but also found a correlation between knowledge and approval.4 Given the limited current information in the literature about physicians and health care reform, it is imperative to understand what physicians know about the ACA.7 In particular whether or not there are differences among primary care and other specialties as the ACA may affect physicians differently depending on their specialty.

In this study, we sought to determine how much physicians of different specialties know about the ACA, and how it is related to their endorsement of health reform. In addition, we aimed to describe differences in knowledge and opinions among primary care specialties compared to other specialties.

METHODS

Data and sample

We conducted an online 15 minute survey of 2,000 physicians practicing in California. The sample was obtained from the AMA Master file and consisted of a random sample of all California physicians with a working e-mail address. The inclusion criteria for the study were: 1) active in providing patient care at least part-time, 2) MD degree, 3) practicing in California as determined by the practice address, 4) not in training as a resident or fellow. A total of 559 physicians started the survey, 25 were disqualified because they were trainees (n=7) or not providing any direct patient care (n=18), and 9 participants started but did not complete the survey. Our final analytic sample size consisted of 525 physicians that met inclusion criteria and completed the survey for a response rate of 28%. The survey had 35 questions and was conducted between May 2014 and June 2014. Physicians were sent an initial invitation to participate and if they did not respond, they were sent two additional reminders two weeks apart. The UCLA Human Research Protection Program approved the study.

Measures

The main outcome was physician endorsement or support of the ACA. We assessed physician support of the ACA by asking them two questions: 1) The Affordable Care Act, if fully implemented, would turn United States health care in the right direction? (strongly disagree to strongly agree);5 and 2) From what you’ve heard or read, do you think the current health care law will most (hurt my practice, help my practice, will not have an effect).

The primary predictor variable was knowledge of health care reform as measured with 10 survey items that were adapted from the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF),8 and also used by Rocke et al. (2014) to survey otolaryngology physicians.4 We used 8/10 questions from the KFF survey and excluded 2 questions that asked participants about health reform and small businesses. Instead, we added 2 items that asked participants, 1) Does the health care reform law increase Medicare payroll tax on earnings for upper income Americans?, and 2) Does the health care reform law create health insurance exchanges or marketplaces where individuals can shop for insurance and compare prices and benefits? To assess physicians’ familiarity with the ACA, we asked, “How well do you feel you understand what’s in the current health care law? (Not at all, not too well, somewhat well, very well).

We put physicians into one of two categories based on their specialty: primary care (family medicine, general internal medicine, geriatrics, general pediatrics, and general practice) versus other specialties. We also created a second clinical specialty categorical variable that categorized respondents based on a specialty classification system previously published (primary care, surgery, procedural specialty, nonprocedural specialty, or nonclinical specialty) (Appendix A).

Satisfaction with practicing medicine was measured by asking respondents, “Overall, how satisfied are you with practicing medicine? (very satisfied, satisfied, not satisfied, or very dissatisfied). We also queried physicians about their practice size (> 25 physicians, 11–25 physicians, 4–10 physicians, or < 4 physicians), hours in patient care (part time versus fulltime), participation in California’s insurance exchange (Covered California) (yes, no, no but plan to participate, or don’t know), practice compensation type (salary only, salary plus bonus, billing only, or other), and self-characterization of political views (very conservative, somewhat conservative, independent/moderate, somewhat liberal/progressive, very liberal/progressive, other).5 Other demographic survey measures were age (continuous variable), gender, and race-ethnicity (White, Black, Latino, Asian/Pacific Islander, Other).

Missing data ranged from 4.6% to 5.3% for the 10 knowledge questions. Demographic variables with the highest missing data were gender, race-ethnicity, and self-characterization of political views, at 6.3%, 5.7%, 4.9% respectively. Missing observations for other demographic and practice-level variables ranged from 0.4% to < 4.9% for age, practice size, and type of compensation. Case wise deletion was used to account for missing data.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics including means and ranges were calculated for all survey variables. Cross tabulations were conducted for physician demographic and practice characteristics by physician specialty groups. Variables for physician familiarity (one item), support (two items), and knowledge (10 items) were each cross tabulated and graphically displayed by physician specialty groups. We calculated the mean number of correct knowledge questions answered and computed the mean by primary care specialty versus other specialties. We summed the number of correct questions and created a continuous variable (0–10) for knowledge of the ACA. Statistically significant associations were assessed with Chi-squared tests for categorical variables and one-way ANOVA for continuous variables.

To determine if the sum of the correctly answered knowledge questions was independently associated with support of the ACA, we computed 2 logistic regression models. Based on the literature,4,5 we controlled for age, gender, race-ethnicity, clinical specialty, practice compensation type, and political views. We also controlled for satisfaction with the practice of medicine because we hypothesized that this was a likely source of bias and that those that were dissatisfied with medicine would not endorse health reform.

We used Stata 11.1 software (Stata Corporation LP 2011, College Station, TX) for all analyses and we considered a P-value of < 0.05 to indicate statistically significant differences when comparing groups.

RESULTS

Table 1 reports physician demographic, practice, and other characteristics. Participants had a mean age 53.6 (+/− 9.7) years and were majority female (65%) and White (68.3%). The majority (75%) of participants self-reported full time practice, and 51% was part of a practice group of > 25 physicians. Sixty-five percent of physicians self-reported participating in California’s healthcare insurance exchange. Primary care physicians were more likely to be younger (mean age of 50 (+/−8) versus 55 (+/−10) years; P < 0.001), females (52% versus 28%; P <0.001), ethnic minorities (Black, Latino or Asian/Pacific Islander; 49% versus 25%; P < 0.001), practice part-time (32% versus 23%; P =0.03), practice in an office with > 25 physicians (63% versus 46%; P< 0.006), and self-report being very liberal/progressive (26% versus 15%; P < 0.05), compared to physicians form other specialties.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Physician characteristics | All respondents (n=525) % |

Primary care physicians† (n=158) % |

Other specialties§ (n=367) % |

P- value‡ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| < 40 | 7.66 (39) | 10.53 (16) | 6.44 (23) | <0.001* |

| 40 – 59 | 64.64 (329) | 76.32 (116) | 59.66 (213) | |

| 60 – 65 | 16.31 (83) | 10.53 (16) | 18.77 (67) | |

| ≥ 65 | 11.39 (58) | 2.63 (4) | 15.13 (54) | |

| Female | 64.84 (319) | 51.97 (79) | 27.65 (94) | <0.001* |

| Race-ethnicity | ||||

| White | 68.28 (338) | 51.35 (76) | 75.50 (262) | <0.001* |

| Black | 4.04 (20) | 6.76 (10) | 2.88 (10) | |

| Latino | 7.47 (37) | 14.86 (22) | 4.32 (15) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 19.39 (96) | 26.53 (40) | 16.14 (56) | |

| Other | 0.81 (4) | 0.00 (0) | 1.15 (4) | |

| Patient care | ||||

| Part time | 25.33 (133) | 31.65 (50) | 22.62 (83) | 0.03* |

| Full time | 74.67 (392) | 68.35 (108) | 77.38 (284) | |

| Size of practice | ||||

| >25 physicians | 51.05 (267) | 62.66 (99) | 46.03 (168) | 0.006* |

| 11–25 physicians | 14.15 (74) | 11.39 (18) | 15.34 (56) | |

| 4–10 physicians | 19.69 (103) | 15.82 (25) | 21.37 (78) | |

| < 4 physicians | 15.11 (79) | 10.13 (16) | 17.26 (63) | |

| Specialty | ||||

| Family Medicine | 12.95 (68) | 43.04 (68) | -- | -- |

| General Internal Medicine | 9.14 (48) | 30.38 (48) | -- | |

| General Pediatrics | 7.62 (40) | 25.32 (40) | -- | |

| General Practice | 0.38 (2) | 1.27 (2) | -- | |

| Surgery | 28.76 (151) | -- | 41.14 (151) | |

| Procedural specialty | 26.29 (138) | -- | 37.60 (138) | |

| Non-procedural specialty | 14.48 (76) | -- | 20.71 (76) | |

| Non-clinical | 0.38 (2) | -- | 0.54 (2) | |

| Participating in exchange | 64.75 (336) | 68.35 (108) | 63.16 (228) | 0.25 |

| Political views | ||||

| Very conservative | 4.58 (23) | 5.30 (8) | 4.27 (15) | 0.05 |

| Somewhat conservative | 19.52 (98) | 15.23 (23) | 21.37 (75) | |

| Independent/moderate | 24.90 (125) | 23.84 (36) | 25.36 (89) | |

| Somewhat liberal/progressive | 31.47 (158) | 27.81 (42) | 33.05 (116) | |

| Very liberal/progressive | 18.53 (93) | 26.49 (40) | 15.10 (53) | |

| Other | 1.00 (5) | 1.32 (2) | 0.85 (3) | |

| Compensation type | ||||

| Billing only | 30.26 (151) | 24.34 (37) | 32.85 (114) | 0.28 |

| Salary only | 24.85 (124) | 26.97 (41) | 23.92 (83) | |

| Salary plus billing | 38.88 (194) | 41.45 (63) | 37.75 (131) | |

| Other | 6.01 (30) | 7.24 (11) | 5.48 (19) |

P < 0.05

= family medicine, general internal medicine/geriatrics, general pediatrics, general practice

= Includes facility based, medical and surgical sub-specialties; 10 missing responses to specialty

Table 2 shows the results for physician opinions about the understanding and support of the ACA by physicians stratified by primary care versus other specialties. Self-reported understanding of the ACA did not statistically vary after stratifying physicians by primary care specialties versus other specialties. Primary care physicians were more likely to strongly agree that the ACA would turn United States health care in the right direction (29% versus 18% for other specialties; P = 0.02), and that the ACA would help their practice (38% versus 20% for other specialties; P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Physician familiarity and support of health care reform for all physicians and by primary care designation versus other physician specialties (n=521)

| Question | All physicians (n=521)* % |

Primary care physicians† (n=159) % |

Other physician specialties‡ (n=362) % |

P -value§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How well do you feel you understand what's in the current health care law? | ||||

| Not At All Well | 5.95 (31) | 5.73 (9) | 6.04 (22) | 0.57 |

| Not Too Well | 17.47 (91) | 15.29 (24) | 18.41 (67) | |

| Somewhat Well | 54.70 (285) | 53.50 (84) | 55.22 (201) | |

| Very Well | 21.88 (114) | 25.48 (40) | 20.33 (74) | |

| The Affordable Care Act, if fully implemented, would turn United States health care in the right direction: | ||||

| Strongly Agree | 21.11(110) | 29.11 (46) | 17.63 (64) | 0.02** |

| Somewhat Agree | 38.00(198) | 37.97 (60) | 38.02 (138) | |

| Somewhat Disagree | 20.15(105) | 16.46 (26) | 21.76 (79) | |

| Strongly Disagree | 20.73(108) | 16.46 (26) | 22.59 (82) | |

| From what you’ve heard or read, do you think the current health care law will most: | ||||

| Help My Practice | 25.14(131) | 38.22 (60) | 19.51 (71) | <0.001** |

| Hurt My Practice | 38.77 (202) | 28.66 (45) | 43.13 (157) | |

| Don’t think it will help | 36.08 (188) | 33.12 (52) | 37.36 (136) |

0.8% missing responses for questions.

family medicine, general internal medicine/geriatrics, general pediatrics, general practice

Includes surgery, procedural specialties, non-procedural, and non-clinical specialties

corresponds to comparison between primary care physicians versus other physician specialties as calculated with x2 tests

P < 0.05

Table 3 describes physician knowledge about the ACA by physician specialty categories (primary care versus other specialties). Physicians had the lowest knowledge (42%) about the ACA and Medicare increases in payroll tax, and about the exclusion of undocumented immigrants (51%). Knowledge was highest about the creation of health insurance exchanges (96%) and about financial aid to low-income Americans (89%). Primary care physician were more likely to know that the ACA does not include a provision for coverage of undocumented immigrants (62% versus 46% for other specialties, P=0.002) and that there are no cuts to traditional Medicare benefits (80% versus 67% for other specialties; P=0.004). Non-primary care specialists were more likely to know that the ACA included increases in payroll taxes for upper income Americans (47% versus 30% for primary care physicians; P = 0.001).

Table 3.

Proportion of physician who correctly answered knowledge questions about the Affordable Care Act

| Knowledge questions | All respondents % (n) |

Primary care physicians† % (n) |

Other specialties‡ % (n) |

P- value§ |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Does the health care reform law require nearly all Americans to have health insurance starting in 2014 or else pay a penalty/fine? (n=501) | 77.84 (390) | 80.00 (120) | 76.92 (270) | 0.45 |

| 2. | Does the health care reform law establish a government panel to make decisions about end of life care for people on Medicare? (n=497) | 71.63 (356) | 70.62 (106) | 72.05 (250) | 0.75 |

| 3. | Does the health care reform law give states the option of expanding their existing Medicaid program to cover more low income, uninsured adults? (n=497) | 87.83 (436) | 86.84 (132) | 88.12 (304) | 0.69 |

| 4. | Does the health care reform law allow undocumented immigrants to receive financial aid help from the government to buy health insurance? (n=501) | 51.10 (256) | 61.59 (93) | 46.57 (163) | 0.002* |

| 5. | Does the health care reform law increase Medicare payroll tax on earnings for upper income Americans? (n=499) | 41.68 (208) | 30.26 (46) | 46.69 (162) | 0.001* |

| 6. | Does the health care reform law require employers with 50 or more employees to pay a fine if they don’t offer health insurance? (n=498) | 85.34 (425) | 86.67 (130) | 84.77 (295) | 0.58 |

| 7. | Does the health care reform law cut benefits for people in the traditional Medicare program? (n=499) | 70.74 (353) | 79.61 (121) | 66.86 (232) | 0.004* |

| 8. | Does the health care reform law provide financial aid help to low and moderate income Americans who don’t get insurance through their jobs to help them purchase coverage? (n=497) | 88.73 (441) | 91.45 (139) | 87.54 (300) | 0.20 |

| 9. | Does the health care reform law create a new government run insurance plan to be offered along with private plans? (n=497) | 67.81 (337) | 70.86 (107) | 66.47 (230) | 0.34 |

| 10. | Does the health care reform law create health insurance exchanges or marketplaces where individuals can shop for insurance and compare prices and benefits? (n=499) | 95.59 (477) | 94.74 (144) | 95.97 (333) | 0.54 |

Note: The average number of questions for all physicians was 7.0/10 (+/−2.4). Primary care physicians answered on average 7.2/10 (+/−2.3) correct questions compared to 6.9/10 (+/−2.4) correct questions for other physicians from other specialties (P=0.22).

P < 0.05

family medicine, general internal medicine/geriatrics, general pediatrics, general practice

Includes surgery, procedural specialties, non-procedural, and non-clinical specialties

corresponds to comparison between primary care physicians versus other physician specialties as calculated with χ2 tests

The average number of correctly answered questions for all physicians was 7.0/10 (+/−2.4). Primary care physicians answered on average 7.2/10 (+/−2.3) correct questions compared to 6.9/10 (+/−2.4) correct questions for physicians from other specialties (P=0.22). Finally, we also found variation in knowledge of the ACA by specialty using the categorical clinical specialty variable (Appendix A).

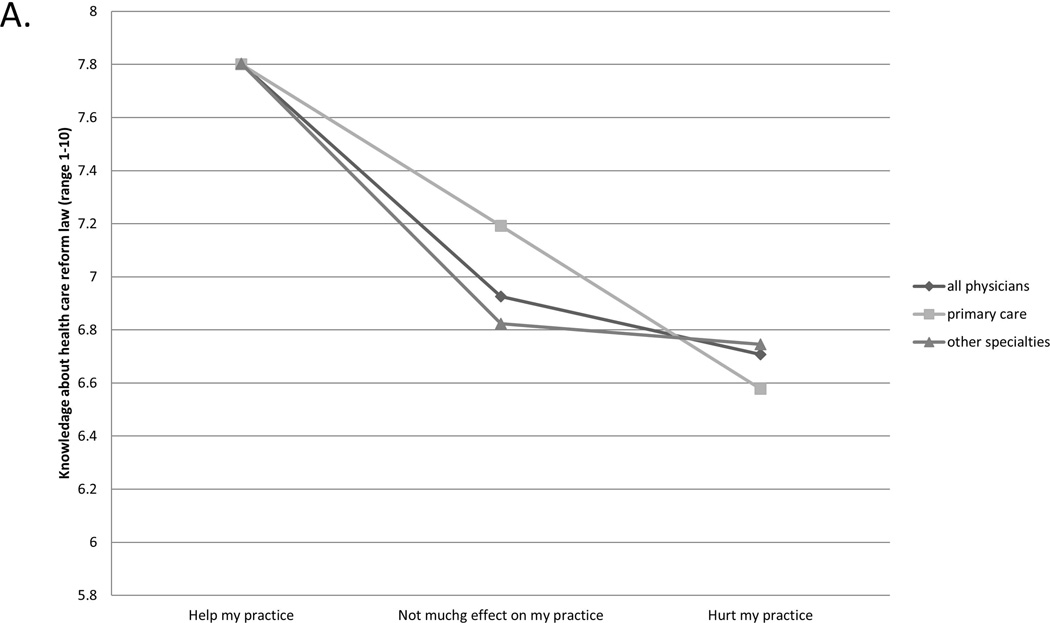

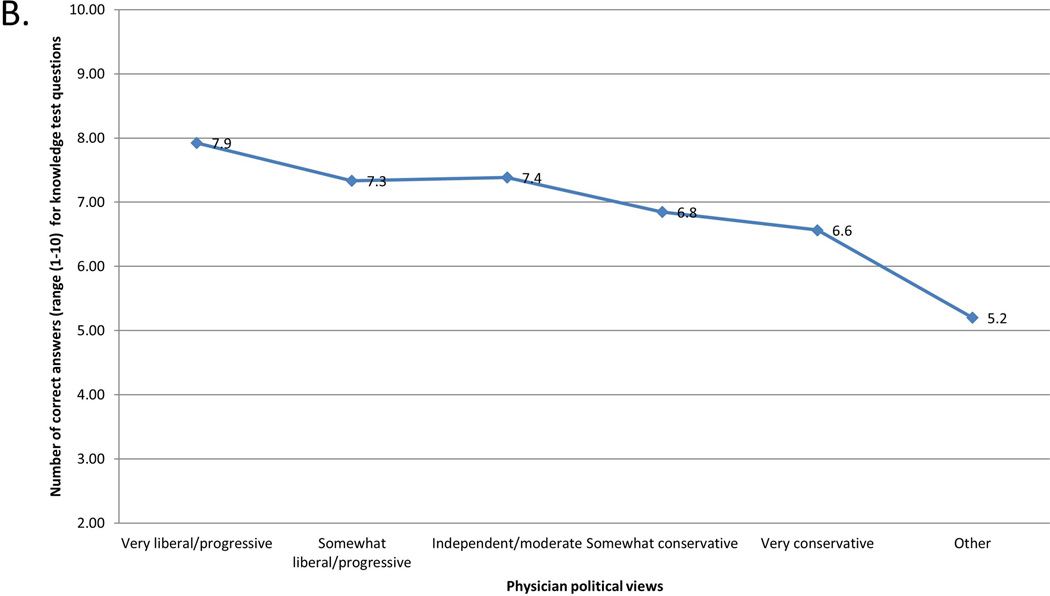

Figure 1 shows the unadjusted relationship between physician knowledge score and political self-characterization, and between knowledge and perceived impact of ACA on their medical practice. Respondents with higher knowledge of the ACA were more likely to be of liberal political views and believe that health reform would help their practice.

Figure 1.

Physician knowledge score (range 1–10) by (A) physician self-characterization of political views and (B) perceived impact on practice

Table 4 reports adjusted odds ratios (AOR) for physician characteristics predicting endorsement and support of the ACA. In the first model, the knowledge score (AOR 1.46; 95% confidence intervals [CI] 1.21, 1.76; p < 0.001) and satisfaction with the practice of medicine (AOR 3.08; 95% CI 1.16, 8.15; p = 0.02) were each independently associated with physician’s self-report that the ACA will help their medical practice. Specialty, practice compensation type, and political views were each also independently associated with the belief that the ACA would help the respondents’ medical practice. Procedural specialists were more likely to perceive that the ACA will not help their practice (AOR 0.43; 95% CI 0.22, 0.84; p = 0.01), compared to primary care physicians. In the second model, satisfaction with the practice of medicine (AOR 2.59; 95% CI 1.25, 5.34; p = 0.01) was independently associated with endorsement of the ACA. Practice compensation type and political views were each also independently associated (p < 0.05) with the endorsement of the ACA (Table 4).

Table 4.

Adjusted odds ratios of physician perception that the ACA will help their practice and turn US health care in the right direction

| ACA will most Help Practice |

ACA will turn US health care in the right direction |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | P- value | AOR | 95% CI | P- value | |||

| Knowledge score† | 1.46 | 1.21 | 1.76 | <0.001* | 1.14 | 1.00 | 1.30 | 0.05 |

| Satisfied with practicing medicine | 3.08 | 1.16 | 8.15 | 0.02* | 2.58 | 1.25 | 5.34 | 0.01* |

| Specialty category | ||||||||

| Primary care | reference | --- | --- | --- | reference | --- | --- | --- |

| Nonprocedural specialty | 1.07 | 0.49 | 2.30 | 0.87 | 1.08 | 0.48 | 2.43 | 0.85 |

| Procedural specialty | 0.43 | 0.22 | 0.84 | 0.01* | 0.59 | 0.31 | 1.12 | 0.11 |

| Surgery | 0.26 | 0.12 | 0.57 | <0.001* | 0.79 | 0.41 | 1.49 | 0.46 |

| Compensation type | ||||||||

| Salary only | reference | --- | --- | --- | reference | --- | --- | --- |

| Salary plus billing | 0.49 | 0.26 | 0.89 | 0.02* | 0.81 | 0.43 | 1.53 | 0.52 |

| Billing only | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.39 | <0.001* | 0.44 | 0.23 | 0.84 | 0.01* |

| Other compensation | 0.58 | 0.17 | 1.90 | 0.37 | 0.89 | 0.30 | 2.61 | 0.83 |

| Political views | ||||||||

| Liberal | reference | --- | --- | --- | reference | --- | --- | --- |

| Moderate | 0.29 | 0.15 | 0.57 | <0.001* | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.44 | <0.001* |

| Conservative | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.43 | <0.001* | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.14 | <0.001* |

Models adjusted for age (continuous), gender (male or female), and race-ethnicity (White, Latino, Asian/Pacific Islander, African American, other)

AOR = Adjusted odds ratios

CI = confidence intervals

ACA = Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

P-value < 0.05

number of correct answers out of 10 knowledge questions

DISCUSSION

This study, to our knowledge is one of the first in the peer-reviewed literature to investigate physician opinions and knowledge about the ACA among a diverse group of physician specialties. We found that California physician knowledge of the ACA varied by specialty and that overall familiarity of the ACA was moderate to high (77%). Physician knowledge as measured was independently associated with the endorsement of the ACA and knowledgeable physicians understood that one aspect of the law is specifically intended to favor primary care over procedural care. Satisfaction with the practice of medicine was also independently associated with support and endorsement of the ACA, even after adjusting for political views, specialty, compensation type, knowledge and demographics.

In this study, 59% of physicians agreed that the ACA would turn the US health care in the right direction. A similar study conducted in 2012 of a national sample of physicians found that 41% of physicians endorsed the current health care reform law.5 Our results suggest that providing education about health care reform laws to physicians could potentially change attitudes about health care reform, independent of political views. However, satisfaction with the practice of medicine had a large effect size in regression models and suggests that improving satisfaction with the practice of medicine may also help engage physicians in learning about health care reform.

This study makes a unique contribution to the peer-reviewed literature by extending results of a published study of otolaryngology physicians to include primary care and other specialties. This is one of the first studies to reach across specialties to assess knowledge and describes how it relates to support and endorsement of current health reform. In addition, we describe the relationship between satisfaction with the practice of medicine and support of the ACA.

Other notable results include the finding that support of the ACA was associated with political self-characterization as previously reported in two studies in the literature.4,5 As expected, we show that practice compensation type and clinical specialty are important predictors of attitudes toward the current health care legislation. The results also indicate that physicians in this study are more knowledgeable than the public as compared to the KFF survey conducted before the implementation of the ACA.8

The results have implications for medical student and graduate medical education and training. Our findings suggest that educating students and trainees about healthcare reform could enhance support for legislation that aims to improve the nation’s healthcare. Health policy education is often not included in medical school lectures. If having informed, educated, and engaged physicians is important, then medical schools should include health policy curricula that aim to educate future physicians about important health policy legislation like the ACA. Part of a physician’s ethical responsibility should be to become aware of cost and quality of care and this training could start in medical schools and continued through residency training programs. A well designed curriculum could potentially change early attitudes towards healthcare reform independent of political party affiliations, compensation, and specialty. Moreover, patients often ask physicians questions on things involving health insurance and health care. As such, since physicians are highly respected it is important that they are able to provide objective factual information, especially on topics which generate mainly negative and inaccurate press.

The limitations to this study include response and recall bias as it relies on self-reports that are subject to socially desirable answers. The study’s generalization is limited to allopathic physicians practicing in California. The data is cross-sectional and cannot account for temporal trends in physician opinions but provides an important snapshot in time of the data. We were also unable to distinguish if physicians practiced in academic medical centers where information and education about the ACA might be more readily available.4 There is self-selection bias and the results are biased by coverage error in that physicians without email addresses did not participate in the study. Finally, although our response rate was 28%, we believe this is a good response rate as compared to a recent similar e-mail survey study of health reform,4 and other reports of physician e-mail surveys.9–15

Although we controlled for physician characteristics in the Table 4 analyses, there are notable differences between survey respondents and California physicians. Compared to all California physicians,16 survey respondents were more likely to be female (64.8% versus 31.4%), white non-Hispanic (68.3% versus 61.7%), Latino ethnicity (7.4% versus 4.1%), and African American (4% versus 3%). Respondents were less likely to be Asian (19.3% versus 25%) compared to all California physicians. The proportion of survey respondents was similar to that for the state of California for physicians >60 years (27% versus 30%) but not for physicians < 40 years of age (8% versus 39%).17 The majority of survey respondents were between the ages of 40 and < 60 years. Although it is difficult to determine how the specialties of survey participants compare to the specialties of all California physicians, available data indicates that the proportion of family medicine physicians in our sample is similar to the proportion in the state (13% versus 10–12%).16,18

In summary, this is one of the few studies that reports physician knowledge and opinions about the ACA among primary care physicians and other specialties. We found that California practicing physicians have moderate knowledge of the ACA. Our results may help inform policymakers’ outreach and education efforts targeted for practicing physicians.

Supplementary Material

Appendix A Physician knowledge of health reform law by specialty categories

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

FUNDING AND FINANCIAL SUPPORT:

Sheila Ganjian was supported by the University of California, Los Angeles UCLA Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI) as a TL1 scholar under NIH/NCRR/NCATS Grant Number UL1TR000124. Dr. Moreno received support from an NIA (K23 AG042961) Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award, and the University of California, Los Angeles, Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research Center for Health Improvement of Minority Elderly (RCMAR/CHIME) under NIH/NIA Grant P30-AG021684. Contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH

Footnotes

Conflict Disclosures: none

REFERENCES

- 1.Iglehart JK. Implementing the ACA: onward through the thorns. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013 Sep;32(9):1518. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blumenthal D, Collins SR. Health care coverage under the Affordable Care Act--a progress report. N Engl J Med. 2014 Jul 17;371(3):275–281. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr1405667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Physician perspectives about health care reform and the future of the medical profession. Deloitte Center for Health Solutions; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rocke DJ, Thomas S, Puscas L, Lee WT. Physician knowledge of and attitudes toward the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014 Feb;150(2):229–234. doi: 10.1177/0194599813515839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antiel RM, James KM, Egginton JS, et al. Specialty, political affiliation, and perceived social responsibility are associated with U.S. physician reactions to health care reform legislation. J Gen Intern Med. 2014 Feb;29(2):399–403. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2523-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Antiel RM, Curlin FA, James KM, Tilburt JC. Physicians' beliefs and U.S. health care reform--a national survey. N Engl J Med. 2009 Oct 1;361(14):e23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0907876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colla CH, Lewis VA, Shortell SM, Fisher ES. First national survey of ACOs finds that physicians are playing strong leadership and ownership roles. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014 Jun;33(6):964–971. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Henry L . Kaiser Family Foundation. [Accessed July 1, 2014];Pop Quiz: Assessing Americans’ familiarity with the health care law. Kaiser Public Opinion Data Note. 2011 Feb; http://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/8148.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiGirolamo A, Geller AC, Tendulkar SA, Patil P, Hacker K. Community-based participatory research skills and training needs in a sample of academic researchers from a clinical and translational science center in the Northeast. Clinical and translational science. 2012 Jun;5(3):301–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-8062.2012.00406.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grava-Gubins I, Scott S. Effects of various methodologic strategies: survey response rates among Canadian physicians and physicians-in-training. Canadian Family Physician. 2008;54:1424–1430. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Antonio AL, Astin HS, Cress CH. Commuinty Service in Higher Education: A Look at the Nation's Faculty. Review of Higher Education. 2000;23(4):373–297. [Google Scholar]

- 12. [Accessed online August 14, 2014];A survey of America’s physicians: Practice patterns and perspectives. The Physicians Foundation. 2012 Sep; http://www.physiciansfoundation.org/uploads/default/Physicians_Foundation_2012_Biennial_Survey.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahlers-Schmidt CR, Chesser A, Hart T, Jones J, Williams KS, Robert Wittler R. Assessing Physician Response Rate Using a Mixed-Mode Survey. KJM. 2010;3(5):1–6. 2010; 3(5):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beebe TJ, Locke GR, 3rd, Barnes SA, Davern ME, Anderson KJ. Mixing web and mail methods in a survey of physicians. Health Serv Res. 2007 Jun;42(3 Pt 1):1219–1234. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leece P, Bhandari M, Sprague S, et al. Internet versus mailed questionnaires: a controlled comparison (2) Journal of medical Internet research. 2004 Oct 29;6(4):e39. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.4.e39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grumbach K, Odom K, Moreno G, Chen E, Vercammen-Grandjean C, Mertz E. California Physician Diversity: New Findings from the California Medical Board Survey UCSF Center for California Health Workforce Studies, 2008. [Accessed October 15, 2014]; (Available at: http://people.healthsciences.ucla.edu/institution/publication-download?publication%5fid=2080075.

- 17.2011 State Physician Workforce Data Book. AAMC Center for Workforce Studies. 2011 Nov [Google Scholar]

- 18.California Healthcare Almanac. California Physician Facts and Figure. California: Healthcare Foundatiuon: 2010. Jul, [accessed October 17, 2014]. (Availabel at: http://www.chcf.org/~/media/MEDIA%20LIBRARY%20Files/PDF/C/PDF%20CaliforniaPhysicianFactsFigures2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix A Physician knowledge of health reform law by specialty categories