Abstract

Although at first relatively disinterested in race, modern genomic research has increasingly turned attention to racial variations. We examine a prominent example of this focus—direct-to-consumer racial admixture tests—and ask how information about the methods and results of these tests in news media may affect beliefs in racial differences. The reification hypothesis proposes that by emphasizing a genetic basis for race, thereby reifying race as a biological reality, the tests increase beliefs that whites and blacks are essentially different. The challenge hypothesis suggests that by describing differences between racial groups as continua rather than sharp demarcations, the results produced by admixture tests break down racial categories and reduce beliefs in racial differences. A nationally representative survey experiment (N = 526) provided clear support for the reification hypothesis. The results suggest that an unintended consequence of the genomic revolution may be to reinvigorate age-old beliefs in essential racial differences.

Keywords: genomic research, racial attitudes, media impact

Race, as a “fundamental axis of social organization in the U.S.” (Omi and Winant 1994:13), is associated with profound levels of social and economic stratification (Feagin 2001; Massey and Denton 1998; Oliver and Shapiro 2006). The “genomic revolution” is a contemporary social phenomenon with the potential to significantly alter beliefs about essential racial differences. Although modern genomic research initially was not much concerned with racial differences, increasing attention has focused on genetic variations based on race and continental or geographically defined population groups. One prominent example is the proliferation of direct-to-consumer ancestry tests that use an individual’s DNA to assign the person into mixtures of population groups that correspond to traditional social categorizations of race. We focus on “admixture tests” as a specific case example of whether the current surge in human genomic research may lead to race reification, because exposure to information about the methods and results of these tests has the potential to promote or reduce belief in racial difference.

On one hand, the methodology of the tests reify race as a genetic and biological reality by indicating that race can be identified by genetic tests. According to the “reification hypothesis,” this may in turn reinforce public beliefs that racial groups are essentially and fundamentally different. On the other hand, admixture tests generally report that individuals have mixed racial backgrounds and that racial differences are characterized as continua rather than as sharp categorical demarcations. Based on the central role played by categorization in the construction of ingroups and outgroups (Brewer and Brown 1998), an alternate “challenge hypothesis” proposes that learning about the results of admixture tests may challenge rather than reify racial categories and break down beliefs in essential racial differences.

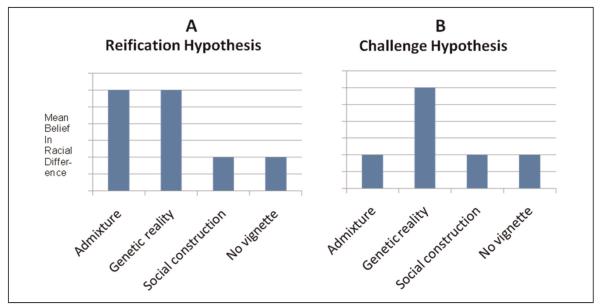

The increasing popularity of admixture tests and their prominence in the media, coupled with their potential to increase or to decrease beliefs about race reification, compelled us to undertake a study testing the competing predictions. We first sought to document our impression about media coverage of admixture tests via a content analysis. We then conducted a survey experiment that randomly assigned participants to read one of three vignettes, closely based on actual news stories, or to read no vignette. The vignette of primary interest describes the administration of an admixture test to a college class. The two comparison vignettes described race as a social construction or as being firmly based in genetic differences. Our primary dependent variable is participants’ endorsement of essential differences between racial groups. The reification hypothesis will be supported if endorsement of essential racial differences in the admixture vignette group is high and similar to that in the race as genetic reality vignette. The challenge hypothesis will be supported if endorsement of essential racial differences in the admixture vignette group is low and similar to that in the race as social construction vignette.

BELIEFS IN RACIAL DIFFERENCE AS A CENTRAL COMPONENT OF RACISM

According to Omi and Winant (1994:71): “A racial project can be defined as racist if and only if it creates or reproduces structures of domination based on essentialist categories of race,” and according to Feagin (2001:70), “the perpetuation of systemic racism requires an intertemporal reproducing not only of racist institutions and structures but also of the ideological apparatus that buttresses them.” Moreover, the extremity of beliefs in essential racial distinctiveness has been correlated with the severity of racial discrimination across history. In what Omi and Winant identify as the “scientific” racial formation of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, renowned intellectuals declared the essential differentness between racial groups. For example, Hegel wrote “there is nothing remotely humanized in the Negro’s character” (Fanon 1967:116). While still robust, racial discrimination and expressions of racist ideology today are concomitantly milder. In Omi and Winant’s (1994) analysis, there has been a shift from the scientific to the “political” racial formation, in which race is regarded as a social rather than an essential and biological concept.

These historical associations by no means imply a unidirectional causal path from racial beliefs to other facets of racism. Nevertheless, Link and Phelan (2001) argued that changes in any one component of stigma affects other components and in turn the overall level of stigma. In this way, increased belief in the distinctiveness of black and white people may exacerbate all aspects of racism. Consistent with this reasoning, Phelan, Link, and Feldman (2013) and Bastian and Haslam (2006) found whites’ beliefs in essential racial differences to be related to implicit racial bias, social distance, and racial stereotyping.

RACE AND THE GENOMIC REVOLUTION

In the late twentieth century, the Human Genome Project (HGP) emerged as a historic scientific undertaking. Although the human genome map was completed in 2003, research on the human genome continues to expand under the National Human Genome Research Institute. While what has been called the “scientific racism” of the nineteenth century and the eugenics movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were overt parts of the ideological machinery of racism, the HGP was initiated with a strong focus on improving population health and a notable inattention to hierarchy or even differences based on race or other social categories. The very phrase “the human genome” implies a focus on commonalities among individual humans.

However, as the genomic revolution proceeds, research has increasingly looked to racial, population, or continental (e.g., Native American, Asian, European, and African) differences as the basis for variation in the 0.1 percent of the of human genome that is not shared (Duster 2003; Fullwiley 2007; The International HapMap Consortium 2003; Phelan et al. 2013). Prominent in these new developments are the direct-to-consumer ancestry tests.1 Public interest in ancestry tests has skyrocketed since 2000 when they first became available, with more than 460,000 people having purchased such tests as of 2007 (Bolnick et al. 2007; Royal et al. 2010). Public interest is fueled by coverage in the popular press, notably through a documentary miniseries (“Faces of America”) by African American scholar Henry Louis Gates Jr., which covered genetic ancestry testing on celebrities such as Oprah Winfrey and Meryl Streep (Nelson 2010).2 The primary purposes of the tests are to: (1) identify particular individuals to whom a person is genetically related, (2) identify geographic areas (often these are specific areas of Africa) where one’s ancestors lived, and (3) estimate the proportions of one’s ancestors originating from different populations (e.g., African, European, Asian, and Native American) (Royal et al. 2010). For example, a consumer may be told that he or she has 50 percent African, 40 percent European, and 10 percent Asian ancestry. It is this last type, the so-called racial admixture tests, that we think has particularly high potential to reshape the way the public thinks about racial differences.

Omi and Winant (1994:65) wrote “as a result of prior efforts and struggles, we have now reached the point of fairly general agreement that race is not a biologically given but rather a socially constructed way of differentiating human beings.” Might the genomic revolution serve to continue or reverse the hard-won understanding of race as social rather than biological? In this article, we examine this question as it applies to the proliferation of and publicity surrounding admixture tests. We see the case of admixture testing as particularly informative because the impact of knowledge about the methods and results of these tests has the potential to shift racial attitudes in either a progressive or regressive direction.

THE CASE FOR REIFICATION OF RACIAL DIFFERENCES

Psychological essentialism is the idea that some categories of things (so-called “natural-kind” categories) are viewed by humans as having an essence, while other categories of things (“human artifact” categories) are not (Rothbart and Taylor 1992). According to this concept, people view natural kinds as possessing underlying unique essences that are both specific to the category and immutable (e.g., a cat can’t be changed into a dog). By contrast, human artifact categories are not seen as having an underlying nature and are seen as mutable (a chair can be changed into a bird feeder). Rothbart and Taylor (1992) argue that there is a tendency to view social categories such as race and gender as natural kinds. This coincides with an emphasis on the idea of essentialism in some models of racism. Omi and Winant (1994:181) “understand essentialism as belief in real, true human, essences, existing outside or impervious to social and historical context.” Rothbart and Taylor (1992) argue that a perceived biological or genetic underpinning of a social category increases the tendency to perceive it in essential terms, and Hoffman and Hurst (1990) offer supporting evidence.

In a related literature, it has been argued that the modern genomic revolution promotes a “genetic essentialist” worldview in which genes come to define the essence of humans—who we are at our most essential level and what defines the distinctions and commonalities among us (Lippman 1992; Nelkin and Lindee 1995). At the level of human identity, James Watson said our “DNA is what makes us human” (Lindee 2003:434). And at the level of the individual, each individual’s genetic make-up, in a genetic essentialist view, is what makes him or her distinct from other individuals (Nelkin and Lindee 1995).

If genes are increasingly used to identify our essential nature as individuals and as a species, surely that same thinking will also apply to subgroups of humans such as racial groups. Taken together, psychological and genetic essentialist perspectives suggest that evidence from the human genome that race is embodied in our DNA should bolster the view that racial groups are essentially different. Several commentators have cautioned that the new genomics may reify racial categories as biological (Bolnick et al. 2007; Fujimura, Duster, and Rajagopalan 2009; Nelson 2008), leading to the “molecular reinscription of race” (Duster 2006:427). Empirical support comes from Martin and Parker (1995) who found that to the extent that people explain race as biological rather than social, they also believe group differences are large and immutable.

But what about the case of admixture tests, which remains unaddressed? Two aspects of the tests may serve to reify not only the idea of biologically based race but existing racial categorizations as well. First, the population groups chosen to compare with an individual’s DNA (African, European, Asian, and sometimes Native American) not surprisingly reflect the socially constructed categories that prevail in current popular and official (e.g., census) conceptions of race. This in itself reinforces the supposed validity of these particular categorizations. Second, the tests convey the idea that there is a genetic basis to variations among these groups. For these reasons, we would expect exposure to information about the methods and results of admixture tests to produce the essentializing effects discussed previously. However, another important message communicated by admixture tests may challenge the reification of racial categories.

THE CASE FOR CHALLENGING RACIAL DIFFERENCES

In the case of admixture tests, reification must face a formidable contender. The idea that the categorization of people into distinct groups is the foundation for prejudice and discrimination began with Allport’s seminal work The Nature of Prejudice (Allport 1954) and continues unabated. Brewer and Brown (1998:556) state that “social categorization, as a fundamental cognitive process, is the sine qua non for all current theories and research in intergroup relations.” The causal role played by categorization in these associations is demonstrated in the “minimal group paradigm,” in which research participants are randomly assigned to arbitrarily defined groups that reliably produce ingroup favoritism (Tajfel and Turner 1986).

As noted previously, admixture tests claim to estimate the proportions of one’s ancestors who originated from African, European, Asian, and Native American populations (Royal et al. 2010). Rarely does a test conclude that an individual’s entire ancestry can be traced to any one of these populations. Moreover, discussion of admixture tests often emphasizes that every person has his or her own unique admixture (Gates 2010). Thus, although the population groups from which individuals are mixed are presented as distinct categories, the tests place individuals along multiple continua and do not provide discrete categories within which individual test-takers can be placed. Following from the demonstrated power of categorization to generate beliefs in group differences, a reasonable prediction is that when layered atop preexisting categorical notions of race, this continuous, or “clinal,” notion of (albeit genetic) racial variation will reduce belief in differences between racial groups. As an analogy, no one doubts the role of genes in determining height, but that does not lead us to develop categories of height. Indeed, a central theme of Gates’s series is that “underlying the many faces of America is a ‘fundamental genetic unity”’ (Nelson 2010:4).

There are caveats to this prediction. The human propensity to categorize is powerful (Allport 1954), and the description of racial differences as clinal may be countered by fitting the continuous data into categories. The one-drop rule is an infamous illustration of our ability to do just that. It is also clear that discrimination based on continuous variables such as skin color does occur (Telles 2004). Despite these caveats, the overwhelming importance of categories for prejudice and discrimination and the fact that the results of genetic admixture tests defy such categorization make it quite possible that exposure to information about the results of admixture tests will challenge racial categories and decrease beliefs in essential racial differences. For reification to prevail, it must be strong enough to outweigh the robust connection between categorization and other aspects of prejudice.

RESEARCH STRATEGY AND HYPOTHESES

We identify two competing hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: The reification hypothesis predicts that because admixture tests indicate that race can be identified by genetic tests, the tests suggest that race is a genetic and biological reality and consequently increase belief in essential racial differences.

Hypothesis 2: The challenge hypothesis predicts that because admixture tests report that most individuals have mixed racial backgrounds and that racial differences are characterized as continua rather than as sharp categorical demarcations, the tests challenge traditional racial categories and consequently reduce belief in essential differences between racial groups.

We test these competing predictions with a survey experiment in which a representative sample of Americans is randomly assigned to read one of three mock newspaper articles about race and genetics or to read no article.

Because we wanted to gauge the impact of messages to which the public would actually be exposed, we constructed vignettes that were closely modeled on articles identified in a content analysis of news about race and genomics (Phelan et al. 2013).3 The vignettes were constructed to make them similar in length, standardize the prestige of sources cited, and lower the reading comprehension level. The articles on which the vignettes were modeled were selected to represent news about admixture testing and two strategically selected points of comparison, as described in the following. The vignette of primary interest—the admixture vignette—describes the administration of an admixture test from DNA Print Genomics to a college class (see appendix for vignettes). In order to assess which hypothesis dominates, we constructed the admixture vignette to provide clear and strong statements representing both hypotheses. For example, representing the reification hypothesis are statements indicating that race is genetic: The “DNA test measures a person’s racial ancestry” and “the test shows what continent a person’s ancestors came from. These continents correspond to the major human population groups or races, those of Native American, East Asian, South Asian, European, and sub-Saharan African.” Representing the challenge hypothesis are statements that contradict the categorical nature of race, such as “mixed ancestry is very common,” “most learn that they share genetic markers with people of different skin colors,” and “instead of people being considered either black or white, the test shows a continuous spectrum of ancestry among African-Americans and others.” Although statements like these were found in several articles in our content analysis, this vignette was modeled most closely on Daly (2005) and Wade (2002).

The effect of the admixture vignette is evaluated relative to a control condition in which no vignette was presented and to two vignettes that take opposing positions on the relationship between genes and race. The first comparison vignette, the race as social construction vignette, modeled on Angier (2000) and Henig (2004), emphasizes broad genetic similarities between racial groups and describes race as being socially constructed. The second comparison vignette, the race as genetic reality vignette modeled on Wade (2004) and Leroi (2005), emphasizes broad genetic differences between racial groups and asserts that genomic research confirms the validity of traditionally defined racial groups. A reliable five-item measure of beliefs in essential racial differences, developed for this study, served as the primary outcome measure.

Comparison to the no-vignette condition will tell us whether reading this vignette elevates beliefs in essential racial differences, but it is possible that any discussion of race and genetics would have a similar effect. By comparing the admixture vignette to the two other vignettes, we gain a second evaluative perspective. If participants are influenced by the messages stated in the two comparison vignettes, those reading the social construction vignette should be more likely to express beliefs that racial groups are essentially similar, and those reading the genetic reality vignette should be more likely to express beliefs that racial groups are essentially different. Our primary interest is in responses to the admixture vignette relative to the other conditions. Our competing hypotheses are illustrated in Figure 1. To the extent that the admixture vignette reifies biological race, we should find that it has effects similar to that of the genetic reality vignette. These should differ significantly from the social construction vignette and the no-vignette control condition in terms of belief in racial difference, as shown in Panel A. To the extent that the admixture vignette breaks down racial categories, we would expect it to have effects similar to that of the social construction vignette and the no-vignette control condition. The admixture and genetic reality vignettes should differ significantly in terms of belief in racial difference, as shown in Panel B.4

Figure 1.

Competing Predictions for Belief in Essential Racial Difference by Vignette Condition

It is also possible that the processes motivating both hypotheses are simultaneously at work and balance each other out. In this case, scores on belief in essential racial differences for the admixture vignette would fall between those of the genetic reality and social construction vignettes and might significantly differ from both or from neither of the comparison vignettes. Alternatively, such a result could indicate that neither reification nor challenge processes are set in motion by the admixture vignette.

Under both hypotheses, it is information about genetic difference or similarity that leads to beliefs in racial difference or similarity, respectively. For this reason, we expect belief in genetic racial differences to mediate the impact of messages about admixture tests on more general beliefs in racial differences. We use an item measuring the belief that racial groups differ genetically to address this hypothesis.

Like Condit and Bates (2005), we see belief in essential racial difference as the first step in a chain linking messages about race and genetics to more distal prejudicial racial attitudes and behaviors. We do not expect exposure to one of our news vignettes to have a direct or immediate impact on these more distal attitudes or behaviors. Rather, our conceptualization of the process is that repeated exposure over time to messages like those in our vignettes will strengthen beliefs in essential racial difference and that the effects of the messages will eventually move down the causal chain from beliefs in difference to racial attitudes and behaviors. However, some studies (Condit et al. 2004; Keller 2005; Williams and Eberhardt 2008) have found single exposures to messages about race and genetics to affect more distal measures of racism, acceptance of racial inequality, and social distance. We therefore assess whether exposure to our vignettes affects (among non-blacks) a more distal measure of racism, namely, social distance toward black people.

The experiment was embedded in a large, nationally representative Internet survey, combining the strong internal validity represented by the experimental design with a level of external validity not often obtained in experimental studies in social psychology. Compared to a telephone survey, the Internet format provides a high level of anonymity. This should reduce social desirability bias, which can be a significant problem in research on socially sensitive topics.

Although there is no theoretical reason specific to the reification or challenge hypotheses to expect variation depending on an individual’s social or psychological characteristics, there is evidence that much social cognition is shaped by one’s position in a structure or social category, as experiences associated with such positions may shape the processing of new information (Fiske and Taylor 2008). Therefore, we assessed the generality of our main findings by testing for interactions between vignette version and key sociodemographic variables—race, gender, age, and educational attainment—as well as implicit racial bias.

CONTENT ANALYSIS

The analyses reported here are part of a larger study that also included a content analysis of 189 news stories about race and genetics published by the New York Times and the Associated Press between January 1, 1985, and December 31, 2008. The methodology of the content analysis is described in Phelan et al. (2013) and in an online supplement to this article.

Data from the content analysis were used in three ways for the present article:

to provide the basis for the vignettes employed in the survey experiment;

to indicate the proportion of articles on race and genetics that discussed direct-to-consumer racial ancestry or admixture tests; between 2000 (the year the tests were first used) and 2008, 18 articles discussed these tests, constituting 18 percent of the total articles on race and genetics identified in the content analysis;

to provide a comparison of the admixture vignette to media articles in terms of their relative emphasis on the themes of a genetic basis for race versus racial differences as clinal or continuous.

Ratings (completed by two raters, Intraclass Correlation Coefficient = .61) ranged from 0 to 5, with a higher score indicating greater relative emphasis on the theme of clinal variation. Although the admixture vignette included statements representing both themes, it was rated by both raters as 5, at the extreme “clinal variation” end of the continuum. The mean rating for the 18 news articles that discussed admixture/ancestry tests was 2.3 (standard deviation = 1.6), indicating that the news articles placed much more relative emphasis on the theme of race as genetically based than did our vignette.

SURVEY EXPERIMENT: METHODS

Sample and Data Collection

The survey was administered by Knowledge Networks (KN) as part of the American National Election Studies (ANES). The ANES panel was recruited by KN to be representative of the U.S. population age 18 and older living in households with telephones. Households without Internet access were offered such access in return for completing monthly surveys. Panel members were invited to complete one survey monthly, receiving $10 per survey (see DeBell, Krosnick, and Lupia 2010, for a description of the ANES methodology). In all, 2,409 respondents completed the survey in English between April 9 and May 7, 2009, with a completion rate of 66 percent, and were randomly assigned to one of two survey experiments (the race and genetics experiment or a separate illness, genetics and stigma experiment); the 526 participants whose responses we analyze here took part in the race and genetics experiment. Results are weighted to account for sampling design features and for nonresponse and noncoverage that resulted from the study-specific sample design.

Comparison with the Census

To evaluate sample selection bias, we compared the weighted analysis sample with 2010 census data for gender, educational attainment, and age (see Table 1). Correspondence is excellent in terms of gender, but the sample underrepresents younger people and overrepresents people with higher educational attainment. To assess the possibility that sampling biases affected the findings, results will be examined for their generality across age, educational attainment, and gender.

Table 1.

Comparison of Selected Characteristics of Sample (N = 526)a with 2010 Census Data for Individuals 18 or Older

| Weighted |

||

|---|---|---|

| Sample (percentage) | Census (percentage) | |

| Female | 53 | 51 |

| Some college or more among those 25 or olderb | 66 | 55 |

| Age | ||

| 18 to 44 | 41 | 48 |

| 45 to 64 | 42 | 35 |

| 65 and older | 17 | 17 |

The sample described here includes only participants who responded to one of the three vignettes or were in the no-vignette control group analyzed in this article.

The census reports educational attainment for individuals who are 25 or older.

The Vignettes

Participants were randomly assigned to one of four vignette conditions: the admixture vignette (N = 145), the race as social construction vignette (N = 139), the race as genetic reality vignette (N = 148), or the control group (N = 94), who were asked the same questions as the other participants but read no vignette. Assignment was random, but the probability of being assigned to the no-vignette control was set at a lower level (.17) than the three vignettes (.28 for each). Immediately preceding the vignette, participants were instructed “Please read the following news article.” The vignettes were presented in the form of a two-column newspaper article

Dependent Variables

Multi-item scales were constructed by taking the mean of component items. The vignettes were followed by two questions on acceptance of the vignette message; three questions about race, genetics, and health; and then five questions on belief in essential racial differences.

Belief in essential racial differences (Cronbach’s alpha = .74) is assessed with five items. Except where noted, response options were (4) strongly agree, (3) somewhat agree, (2) somewhat disagree, (1) strongly disagree. Three items were constructed for this study: [1] Although black and white people may be alike in many ways, there is something about black people that is essentially different from white people; [2] Different racial groups are all basically alike “under the skin” (reverse scored); [3] When you compare black and white people, you think they are very similar (1); somewhat similar (2); not very similar (3); not similar at all (4). Two items were adopted from the General Social Survey: [4] To what extent do you agree with the following statement? Racial and ethnic minority groups in the U.S. are very distinct and very different from one another; [5] To what extent do you agree with the following statement? Whites as a group are very distinct and different from racial and ethnic minority groups.

Belief in genetic racial differences was measured with the item: There are very few genetic differences among racial groups (reverse scored): (4) strongly agree; (3) somewhat agree; (2) somewhat disagree; (1) strongly disagree.

Acceptance of vignette message

To assess the social desirability or acceptability of the three vignettes, we constructed a measure (alpha = .74) composed of two items: [1] In your opinion, the article provided an accurate account of the topics it discussed; [2] The article struck you as biased and inaccurate (reverse scored): (4) strongly agree; (3) somewhat agree; (2) somewhat disagree; (1) strongly disagree.

Social distance from black people (alpha = .73 among non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic other race, and Hispanics; mean of five items): [1] How would you feel about having a close relative or family member marry a black person? (1) strongly favor, (2) favor, (3) neither favor nor oppose, (4) oppose, (5) strongly oppose; [2] would you rather live in a neighborhood where … (4) all of your neighbors, (3) most of your neighbors, (2) about half of your neighbors, (1) most of your neighbors do not … belong to your own racial group; [3] suppose you were … thinking of adopting a child [of a different race from you]. Would the race of the child be a concern for you in thinking about whether to adopt the child? (3) major concern, (2) minor concern, (1) no concern; [4] How would it make you feel to receive a blood transfusion from someone who is of a different race than you? (3) very uneasy, (2) somewhat uneasy, (1) not uneasy at all.

Covariates and Moderating Variables

Because the vignettes were randomly assigned, confounding would only be an issue if randomization failed. Still, we included several sociodemographic variables as well as implicit racial bias to assess the generality of vignette effects across demographic and attitudinal subgroups and to increase the precision of our estimates of vignette effects on belief in racial difference. The variables (weighted data) were age (mean = 48.3, range = 18 to 90), gender (52.6 percent female), educational attainment (6.0 percent twelfth grade or less with no diploma; 33.7 percent high school diploma or equivalent; 22.2 percent some college; 9.4 percent associate degree; 18.5 percent bachelor’s degree; 7.4 percent master’s degree; 2.7 percent professional or doctorate degree), and race/ethnicity (77.1 percent non-Hispanic white; 11.9 percent non-Hispanic black; 3.2 percent other non-Hispanic; 3.4 percent two or more races, non-Hispanic; 4.4 percent Hispanic).

The Affect Misattribution Procedure (AMP) (Bar-Anan and Nosek 2012; Payne et al. 2005) is one of a new generation of measures that attempt to circumvent social desirability bias by measuring bias at an implicit, possibly unconscious level. These measures employ reaction time as an indicator of implicit cognitive associations between different concepts (e.g., the Implicit Association Test, Greenwald, McGhee, and Schwartz 1998) or priming techniques as in the AMP. In the AMP, after seeing a photograph of a young male black or white face for 75 milliseconds, participants see a Chinese character for 100 milliseconds, followed by a patterned screen. Participants then indicate whether they find the Chinese character pleasant or unpleasant. The AMP score is the percentage of characters associated with black faces judged to be unpleasant (scored 2) minus the percentage of characters associated with white faces judged to be unpleasant (scored 1). Cronbach’s alpha = .77 for the difference between pleasantness ratings associated with black and white faces for 24 paired trials.

In order to examine implicit racism as a moderator of the impact of vignette version, it could not be administered after the vignette. Consistent with this requirement, implicit racism was administered to the same participants in a prior wave of the ANES survey.

Analysis

The complex survey design includes stratification by phone exchange and other variables. All analyses reported use general linear models for complex samples in SPSS 18.0 that allow one to take the sampling design into account in estimating standard errors. All analyses use weighted data, and all significance tests are based on procedures to analyze complex samples.

SURVEY EXPERIMENT: RESULTS

Essential Racial Differences

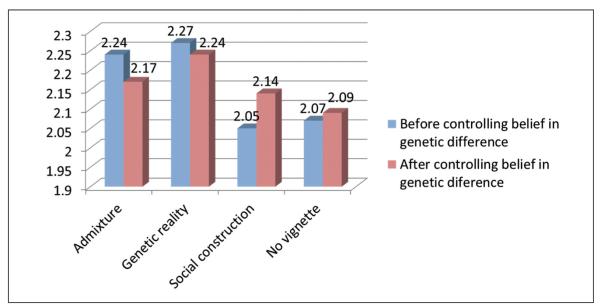

Our key competing hypotheses involve mean belief in essential racial differences for respondents to the admixture vignette in relation to respondents to the two comparison vignettes and to participants who read no vignette. The reification hypothesis is that participants randomly assigned to read the admixture vignette will be significantly more likely than those assigned to the race as social construction vignette or to the no-vignette control condition to endorse beliefs that racial groups are essentially different but will not differ significantly from those reading the race as genetic reality vignette. Results shown in Figure 2 (left-hand bars) clearly support the reification hypothesis. Controlling for age, gender, education, non-Hispanic white race, and implicit racial bias, mean belief in essential racial differences varied significantly among the four vignette conditions (p < .05). More specifically, using dummy variables to compare the admixture vignette with the other three experimental conditions, mean belief in essential differences between racial groups was nearly identical (and not significantly different) for participants assigned to the admixture vignette (2.24 on a 4-point scale) and the genetic reality vignette (2.27). Endorsement of essential racial differences is substantially lower among participants assigned to the social construction vignette (2.05; differs from the admixture vignette at p < .05) and the no-vignette control condition (2.07; differs from the admixture vignette at p < .05). The difference between the admixture vignette and the social construction vignette is .47 of a standard deviation in belief in essential racial differences, and the difference from the no-vignette control group is .43 of a standard deviation.

Figure 2.

Results: Mean Endorsement of Essential Racial Differences by Vignette (1 to 4 scale). Note: Before controlling belief in genetic difference, the overall model and difference of social construction and no vignette control from admixture are significant at p < .05, two-tailed tests. After controlling belief in genetic difference, no statistically significant differences between vignette conditions remain. All models control for gender, education, age, non-Hispanic white race, and implicit racial bias.

Mediation by Belief in Genetic Racial Difference

We hypothesized that vignettes would influence belief in racial differences in part by influencing belief in genetic racial differences specifically. This hypothesis was supported. As shown in Figure 2 (right-hand bars), adding belief in genetic racial difference to the model decreased the differences between vignette conditions, and after adding the variable to the model, both the overall model and differences between the admixture vignette and both the social construction vignette and the no vignette control condition became nonsignificant. The degree of mediation was substantial. The difference in belief in racial difference between the admixture vignette and the no-vignette control condition was roughly halved, and the difference between the admixture and social construction vignettes was reduced by nearly 85 percent.

Moderation of Vignette Effects by Sociodemographic and Attitudinal Factors

We assessed the generality of these findings by examining whether results varied significantly across race (non-Hispanic black vs. white, the two largest racial groups in our sample), gender, age, educational attainment, and implicit racial bias. To avoid Type II error, we enter the interaction terms as a set and evaluate individual interactions only if the set as a whole increases explained variance in belief in essential racial difference. However, differential responding by race is of particular interest, because the vignette messages focus on race and genetics. For this reason, we investigated the role of race in more detail. There was no significant main effect of race on belief in racial difference or belief in genetic racial difference, before or after controlling for the other covariates (age, gender, education, and implicit racial bias). See table in online supplement for mean values of belief in essential racial difference by vignette and race/ethnicity. There also was no significant interaction between race and vignette version in predicting belief in racial difference or belief in genetic racial difference, before or after controlling for the other covariates. Being male (p < .05), less educated (p < .05), and more implicitly biased (p < .01) were significantly associated with greater belief in racial difference. However, the critical question for evaluating the impact of the vignettes is whether these interact significantly with vignette version in their impact on belief in racial difference. They do not, nor does age. These results suggest that the vignettes affect blacks and whites, women and men, the old and the young, those with more and less education, and those high and low on implicit racial bias in much the same way. Significantly, the results are not specific to or driven by those high on racial bias or by any particular demographic subgroup.

Social Distance from Black People

Although such an effect was not hypothesized, we assessed whether support for the reification hypothesis would extend to a more distal measure of racism, namely, social distance from black people. We repeated the analysis performed for essential racial differences, substituting social distance as the dependent variable and eliminating black and multiracial participants from the analysis (analysis N = 444). Controlling for age, gender, education, and implicit racial bias, mean social distance did not vary significantly among the four vignette conditions (p = .815).

Acceptance of Vignette

The degree to which participants explicitly accept a vignette’s message (that is, evaluate it as accurate and unbiased) can be viewed as a measure of the message’s social desirability or acceptability. Table 2 shows that acceptance of the three vignettes differed significantly (p<.001). Acceptance was highest (mean of 3.18 on a 4-point scale) for the race as social construction vignette and lowest (2.80) for the race as genetic reality vignette. Interpreting acceptability as a measure of social desirability, this suggests that the message that race is socially constructed is generally viewed as the most socially acceptable point of view. Acceptance of the admixture vignette falls in between the two comparison vignettes and is closer to and not significantly different from the race as social construction vignette. Acceptance of the admixture vignette does differ significantly from the race as genetic reality vignette (p<.01). This suggests that any similarities in the underlying messages of the admixture and the race as genetic reality vignettes are not identified by participants in a way that would cause them to view the admixture vignette as biased, even though the two vignettes have nearly identical effects on participants’ belief in essential racial differences.

Table 2.

Mean Acceptance of Vignette by Vignette Condition

| Acceptance of vignette (N = 434) | |

|---|---|

| Admixture Vignette | 3.08 |

| Race as Genetic Reality Vignette | 2.80** |

| Race as Social Construction Vignette | 3.18 |

| Overall | 3.02*** |

Note: Statistical significance reported for each comparison condition contrasted with the admixture vignette and for the overall difference among the three vignettes, controlling for gender, education, age, non-Hispanic white race, and implicit racial bias. The mean acceptance is an evaluation of a vignette as accurate and unbiased.

p < .01.

p < .001.

It also seemed likely that one’s degree of acceptance of the vignette that one was assigned to read would influence the impact of the vignette on belief in racial difference, and this was the case; however, the meaning of the results is difficult to interpret. Vignette version and acceptance interacted significantly (p<.001) in predicting belief in racial difference. Specifically, acceptance of the admixture and social construction vignettes was associated with lower scores on belief in racial difference, while acceptance of the genetic reality vignette was associated with higher scores on belief in racial difference. The findings for the social construction and genetic reality vignettes make sense: greater acceptance of the vignette is associated with racial difference beliefs that are congruent with the message embodied in the vignette. Findings for the admixture vignette, though, are puzzling: acceptance of the vignette’s message is associated with less endorsement of racial differences, yet reading the vignette increases endorsement of racial differences. This seeming contradiction may have to do with the competing messages communicated in this vignette, a feature not shared by the other two vignettes. Explicit acceptance of the vignette may be based on the racial category–challenging aspects of the message (e.g., no one is 100 percent anything) but the race-reifying aspects of the vignette (i.e., race is based on DNA) may at the same time, perhaps not consciously, increase belief in racial difference.

DISCUSSION

This article was motivated by our hypothesis that the modern genomic revolution, exploding in our current time, may significantly alter how people think about race and racial differences. One reason to expect such a consequence is the increased emphasis on the role played by genetic factors in racial differences and “race” itself that has become an important element of modern genomic research and discourse. Theory and research suggest that genetic attributions for racial difference may reify racial categories by making those categories appear more inherent, immutable, essential in nature. There are many current developments, such as research on racial differences in genetic aspects of disease and research aiming to trace the evolutionary development of “racial” groups that share this reifying potential. In this article, we chose to examine one particular development—direct-to-consumer racial admixture tests—for a specific reason. The methods used by these tests and the information they are said to provide contain not only potentially race-reifying elements (race is genetically determined), but also elements that could strongly challenge the idea of racial categories (race must be viewed in continuous rather than categorical terms). Because of the strong and well established role of categorization in the creation and maintenance of prejudice, admixture tests provide a rigorous test of the race-reifying power of genetic essentialism. Despite explicit statements in the admixture vignette that the tests break down either–or distinctions between racial groups, thus directly challenging the categorical basis of race, the reification hypothesis clearly prevailed. We found that participants randomly assigned to read the admixture vignette had beliefs in essential racial differences that were very close to those of participants who read a vignette emphasizing race as genetic reality but that were significantly higher than those of participants who read a vignette emphasizing race as social construction or participants who read no vignette. Note that we do not interpret these findings as challenging the well documented importance of social categories for generating prejudice. Rather, we take the findings to indicate that the race-reifying processes set in motion by the admixture vignette were sufficiently strong to overpower the breaking down of us-them categories that should also have been set in motion by the vignette.

Strengths, Limitations, and Remaining Questions

We evaluate our confidence in the conclusions we can draw from the perspective of two questions: First, how does exposure to our admixture vignette affect individuals’ beliefs about essential racial differences; second, what will be the impact of information like that contained in the vignette on population trajectories of racial beliefs?

Effect of admixture vignette on beliefs of those exposed to it

Because of our experimental design, the observed associations between the type of article read and belief in essential racial differences cannot be attributed to confounding factors, and we can be confident that these associations reflect the causal impact of the story content on belief in racial difference. Because the experiment was embedded in a nationally representative survey and because the key results were relatively constant across sociodemographic subgroups of the population, we can conclude that the findings are reasonably representative of the adult U.S. population.

Social desirability bias may affect expressed beliefs in essential racial differences, but such bias is unlikely to explain our pattern of results. Vignette acceptability, or social desirability, varied significantly among vignette conditions and did so in a pattern quite different from the pattern of endorsement of essential racial differences. If social desirability bias strongly affected stated beliefs in racial difference, we would expect the patterns for acceptance and for belief in racial differences to be similar—a finding we did not observe.

The vignettes for this study do not follow the typical experimental protocol in which most elements of the vignette are held constant and only very specific elements are varied. Certain features, such as vignette length and prestige of sources cited, were standardized, but each vignette was constructed to represent a kind of message found in recent media coverage of race and genomics, and most of the content was unique to the particular vignettes. While we have identified essentializing race and breaking down categorical notions of race as the operative elements of the vignettes, it is possible that elements of the vignettes other than those of theoretical interest affected participants’ responses. Notwithstanding these possibilities, the admixture vignette affected beliefs in essential racial differences exactly as predicted by the reification hypothesis.

To the extent that the vignettes were effective in influencing participants’ beliefs about essential racial differences, another possible shortcoming is raised, that is, that the study had the unintended consequence of increasing belief in racial differences among study participants who read the admixture or the race as genetic reality vignette. Three considerations allay our concern about this possibility. First, participants were debriefed by being informed that the article they read was constructed from a variety of different news articles and reflected only one viewpoint among many views on the issue. Second, the vignettes closely mimicked actual news articles, and as a consequence did not differ significantly from what participants might be exposed to in the media. Most importantly, as we argue in the following, we do expect messages linking race and genetics to have enduring effects on beliefs about racial difference and consequently other aspects of racism, but we expect these changes to take place gradually as a result of repeated exposures to such messages. In this scenario, we are relatively comfortable that exposing 292 individuals to a single race-reifying message will not have a meaningful impact on racism. Certainly, we believe that the overall impact of this research will be to reduce rather than increase harmful racial beliefs and attitudes.

Population impact

We must be more cautious in our conclusions about the impact of exposure to information about the methods and results of admixture tests on beliefs in essential racial differences in the U.S. population because we lack a direct measure of public exposure to the messages represented by our vignettes. Having such data would strengthen our confidence that such messages are affecting the racial beliefs of the general population. We do know, however, that over half a million people have purchased some kind of ancestry test. Also, our content analysis showed that a sizable proportion (18 percent) of all news articles we identified between 2000 and 2008 discussing the topic of race and genetics addressed direct-to-consumer racial ancestry and admixture tests.

Moreover, in gauging the likely population impact of essentializing messages about race, we think it is valid to look beyond admixture tests specifically to the cultural prominence of a broader discussion of genetic bases of race and racial difference. The reifying elements in the admixture vignette are also represented in many other currently prominent topics, such as racial differences in genetic aspects of disease (Phelan et al. 2013) and genetic distinctiveness between populations that correspond to traditionally defined racial groups (as described in the race as genetic reality vignette). Using this broader lens, we found that articles in the New York Times and the Associated Press that combined the topics of race and genomics or genetics have increased significantly since 1985, five years before the initiation of the Human Genome Project (Phelan et al. 2013).

Finally, it is important to note that if the public is regularly exposed to such messages, which we believe is a reasonable assumption, our findings probably underestimate their effects in the population over time, for three reasons. First, our findings were based on a single presentation of a single story. The magnitude of the impact of the admixture vignette, compared to the social construction vignette and no-vignette control group, was between .4 and half a standard deviation in belief in racial differences. This is just slightly smaller than Cohen’s (1988) “medium” effect size; thus, the effect is not trivial. Also, although our assessment of vignette impact was immediate and we did not assess possible lasting effects on attitudes, it is likely that exposure to such messages is repeated over and over, leading us to expect the impact of the messages to be reinforced and strengthened over time. Second, our vignettes were created from news items in two outlets respected for balanced and thorough reporting, the New York Times and the Associated Press. Television, where the majority of people turn for the news (Pew Research Center for the People and the Press 2013), is likely to report messages about race and genetics in an even more simplified, stark, and dramatized manner. Thus the messages that the majority of people actually receive may be even more likely to engender beliefs in essential racial differences than the ones represented in this study. Third, in order to fairly test our competing hypotheses of reification and challenge, we constructed the admixture vignette to strongly represent both the themes that race is based on genetics and that racial differences are continuous rather than categorical. Our content analysis showed that news articles, on average, placed much greater relative emphasis on the genetic basis of race than did our vignette. It seems likely, therefore, that messages actually encountered by the public would be more race-reifying than our vignette.5

Also important for assessing the likely population impact of admixture tests is the fact that the results generalized across race, gender, age, educational attainment, and implicit racial bias. Thus, the results are not limited to or driven by those high on racial bias or by any particular demographic subgroup. This is particularly interesting given the fact that racial beliefs and attitudes often do show sociodemographic variations. In our study, participant gender and education were related to belief in racial difference, but the pattern of influence of the vignettes on these beliefs did not vary by demographic factors or by level of implicit racial bias. This may be because the vignettes involve beliefs and attitudes about race and genetics, and such attitudes have not been as well established and entrenched among certain population groups as have beliefs and attitudes about race. In any event, our results suggest that any population impact will be a broad and general one.

If the public does come to accept the message that racial differences have a genetic basis, these beliefs may exacerbate racism more broadly. Several studies provide evidence for a connection between genetic attributions for racial differences and various measures of racism (Condit et al. 2004; Keller 2005; Kluegel 1990; Williams and Eberhardt 2008). Also notable is the fact that declines in overt racism from the 1970s to the 1990s were accompanied by declines in the attribution of racial socioeconomic status differences to innate factors (Kluegel 1990). The causal relationship between these two trends is unknown. However, Condit et al. (2004:403) point out that these declines largely predate recent scientific and media emphasis on race and genetics and raise the possibility that “racism may have declined across this period in part because biological accounts of race have declined. If that is true, then messages that increase the belief that races are biologically distinct … would increase levels of traditional racism.”

Condit and Bates (2005) proposed a conceptual model for the influence of race-reifying messages on prejudice and discrimination. In their model, messages linking genes, race, and health affect perceived racial difference, which in turn affects hierarchicalization and in turn racism. We concur with these causal paths, which we see as unfolding gradually over time. That is, repeated exposure to messages linking race and genes gradually increases beliefs in racial difference, which in turn, over time, increases hierarchicalization and racism. Consistent with this conceptualization, we did not predict nor did we find an effect of messages about race and genetics on the more distal outcome of social distance from black people. However, three experimental studies have found that a single exposure to messages linking race and genes can have an immediate effect on more distal attitudinal and behavioral-intention measures of racism, including concerns about racial inequalities, social distance, and likability of outgroup members (Condit et al. 2004; Keller 2005; Williams and Eberhardt 2008). Thus, we need to consider the possibility that the impact of race-reifying messages on prejudice and discrimination may be a less gradual process than we have proposed.6

Ultimately, the only way we can know whether messages about race and genomics affect population-level beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, and policies is to track changes in these outcomes over time. However, as Collins (2001) noted, a strength of the Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute, which funded this study, is that it allows social scientists to study the social impact of the genomic revolution as it is occurring. If we wait to observe effects after they have happened, racism may already have been exacerbated, and deleterious changes may be more difficult to reverse. We believe our findings are sufficient to warrant further attention to this issue.

CONCLUSION

In its turn away from its early emphasis on similarities among humans, emblemized by President Clinton’s 2000 statement that “one of the great truths to emerge from this triumphant expedition inside the human genome is that in genetic terms, all human beings, regardless of race, are more than 99.9 percent the same” (Office of International Information Programs 2000) to an increasing emphasis on genetic differences between racial, population, and continental groups, our findings point to the possibility that an unintended consequence of the modern genomic revolution is to magnify the degree, generality, profundity, and essentialness of the racial differences people perceive to exist.

To counter these potential unintended consequences, the advertising of tests, reporting of results to individuals who take them, and media coverage of the general phenomenon need to consider the potential of such tests to essentialize race as a genetic reality. When they are presented or discussed, there should be an explicit indication that there are ways to conceptualize race other than the one delivered by the admixture tests. Further, the fact that only a miniscule portion of the human genome varies between individuals or “racial” groups needs to be reiterated along with a careful description of the actual methodology of the tests and an accurate indication of what information they can and cannot provide. But as our work and that of others shows, the current geneticization of race goes well beyond admixture tests (Duster 2003; Fujimura et al. 2009; Fullwiley 2007; Phelan et al. 2013). Together, this emerging research provides a cautionary tale that funding agencies, genetic scientists, and journalists would do well to heed. Without careful attention to the subtle, under-the-radar influence that occurs when genes and race are linked in research, genetic testing, the media, and ultimately in the minds of the general public, a potent source of a key component of racist belief will be left unchecked.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Claire Espey, MPH, Nicholas Valentino, PhD, Parisa Tehranifar, DrPH, Sara Kuppin, DrPH, and Naumi Feldman, DrPH, for their contributions to the study.

FUNDING The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by grant #5R01HG003380 by the National Human Genome Research Institute and supported by the Russell Sage Foundation. The study reported in the article was funded by the National Institutes of Health, including salary support for Jo C. Phelan.

BIOS

Jo C. Phelan is a professor of sociomedical sciences in the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health. Her research focuses on social conditions as fundamental causes of inequalities in health and mortality; stigma, prejudice, and discrimination, especially with respect to mental illness; and the impact of the genomic revolution on stigma and racial attitudes. She is particularly interested in the interplay between structural conditions and social psychological processes in the creation and reproduction of inequalities.

Bruce G. Link is a professor of epidemiology and sociomedical sciences at the Mailman School of Public Health of Columbia University and a research scientist at New York State Psychiatric Institute. His interests include the nature and consequences of stigma for people with mental illnesses, the connection between mental illnesses and violent behaviors, and explanations for associations between social conditions and morbidity and mortality.

Sarah Zelner is a PhD candidate in sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. She has an MPH from Columbia University and a BA from Bryn Mawr College. Her research interests are in urban sociology and sociology of culture. Her dissertation is an ethnographic study of processes of integration in a diverse urban neighborhood.

Lawrence H. Yang is an associate professor of epidemiology at the Mailman School of Public Health at Columbia University. His research focuses on several areas of psychiatric epidemiology. This includes theoretical and empirical work on how culture (via the “what matters most approach”) is conceputalized in relation to stigma and mental illness, in particular within Chinese groups. He currently has an NIMH R01 grant to examine the neurocognitive and social cognitive underpinnings of the new designation of a “high risk for psychosis.”

APPENDIX. VIGNETTES

The following vignettes were presented in the form of two-column newspaper articles.

Admixture Vignette (N = 145)

“Is It All Black and White? Genes Say ‘No.”’

Most people think they know what race they belong to, and people tend to think of themselves as “100 percent” white or black or something else. A recent study challenges that way of thinking. Dr. Bruce Firman and other geneticists at Columbia University have developed a DNA test that measures a person’s racial ancestry.

Results of the study were published yesterday in the journal Nature Genetics. The test shows what continent a person’s ancestors came from. These continents correspond to the major human population groups or races, those of “Native American, East Asian, South Asian, European, and sub-Saharan African” according to Dr. Firman. If a person is of mixed race, the test shows the percentage of each race in a person’s genetic background.

It turns out that mixed ancestry is very common, said Dr. Firman. About 10 percent of European-Americans have some African ancestry, and African-Americans, on average, have about 17 percent European ancestry.

When people are told the results of their DNA test, they are usually quite surprised. Most learn that they share genetic markers with people of different skin colors. Some “black” subjects in the study found that as much as half of their genetic material came from Europe and some from Asia. One “white” subject learned that 14 percent of his DNA came from Africa and 6 percent from East Asia. Very few were 100 percent anything.

“The main outcome is that we are breaking down an either-or classification,” Dr. Firman said. Instead of people being considered either black or white, the test shows a continuous spectrum of ancestry among African-Americans and others.

Race as Genetic Reality Vignette (N = 148)

“Is Race Real? Genes Say ‘Yes.”’

Most people would agree it is easy to tell at a glance if a person is Caucasian, African, or Asian.

A recent study suggests that the same racial groups we can identify do in fact correspond with broad genetic differences between groups.

Results of the study were published yesterday in the journal Nature Genetics. The study was conducted by Dr. Bruce Firman and other geneticists at Columbia University.

Dr. Firman says that racial differences exist because early humans in Africa spread throughout the world 40,000 years ago, resulting in geographical barriers that prevented interbreeding. On each continent, natural selection and the random change between generations known as genetic drift, caused peoples to diverge away from their ancestors, creating the major races.

The effects of this natural selection and genetic drift that have followed different pathways on each continent can be seen by looking at people from different racial groups as traditionally defined. Certain skin colors tend to go with certain kinds of eyes, noses, skulls, and bodies.

When we glance at a stranger’s face we use those associations to guess what continent, or even what country, he or his ancestors come from—and we usually get it right.

What Dr. Firman and his colleagues showed was that genetic variations that aren’t written on our faces—that can be seen only in our genes—show similar patterns.

The researchers sorted by computer a sample of people from around the world into five groups on the basis of genetic similarity. The groups that emerged were native to Europe, East Asia, Africa, America, and Australasia—the major races of traditional anthropology.

Hence, Dr. Firman says, “race matches the branches on the human family tree as described by geneticists.”

Race as Social Construction Vignette (N = 139)

“Is Race Real? Genes Say ‘No.”’

Most people would agree it is easy to tell at a glance if a person is Caucasian, African, or Asian.

But a recent study suggests that it is not so easy to make these distinctions when one probes beneath surface characteristics and looks for DNA markers of “race.”

Results of the study were published yesterday in the journal Nature Genetics. The study was conducted by Dr. Bruce Firman and other geneticists at Columbia University.

Analyzing the genes of people from around the world, the researchers found that the people in the sample were about 99.9 percent the same at the DNA level. “That means that the percentage of genes that vary among humans is around .01 percent, or one in ten thousand. This is a tiny fraction of our genetic make-up as humans,” noted Dr. Firman.

The researchers also found that there is more genetic variation within each racial or ethnic group than there is between the average genomes of different racial or ethnic groups.

Why the discrepancy between the ease of distinguishing “racial” groups visually and the difficulty of distinguishing them at a genetic level?

Traits like skin and eye color, or nose width are controlled by a small number of genes. Thus, these traits have been able to change quickly in response to extreme environmental pressures during the short course of human history.

But the genes that control our external appearance are only a small fraction of all the genes that make up the human genome.

Traits like intelligence, artistic talent, and social skills are likely to be shaped by thousands, if not tens of thousands of genes, all working together in complex ways. For this reason, these traits cannot respond quickly to different environmental pressures in different parts of the world.

This is why the differences that we see in skin color do not translate into widespread biological differences that are unique to groups and why Dr. Firman says “the standard labels used to distinguish people by ‘race’ have little or no biological meaning.”

Footnotes

The increased attention to racial variation may have been fueled by the increased technological ability to examine variations in the genome, as more and more individuals’ genomes became available for analysis.

Questions have been raised about misrepresentation and misinterpretation of test results (Bolnick et al. 2007). We do not address these issues here; rather we are concerned with the social impact of information about test methods and results as described and delivered.

We chose to base our vignette on media coverage of admixture tests rather than on marketing materials or an example of actual test results because we expect that many more people have been exposed to such tests via the media than by purchasing a test and because the media format allowed us to construct the comparison vignettes, also based on news articles, that were central to our study design.

Responses to the no-vignette control condition depend on baseline levels of belief in essential racial differences, and we had no firm basis for predicting what those levels would be. We have hypothesized these baseline levels to be relatively low, in part because they measure explicit racial beliefs that may be subject to social desirability bias. However, if participants come into the experiment with strong beliefs in racial differences, the admixture vignette might actually reduce those beliefs, in which case belief in racial difference would be significantly lower for the admixture group than for the no-vignette control group.

It would be informative to test this possibility empirically by constructing different versions of the admixture vignette that systematically vary in their relative emphasis on the two themes and assessing their impact on belief in essential racial differences. We thank an anonymous reviewer for this suggestion.

Clarity on how messages about race and genes may affect a broad range of racism-related outcomes over time could be gained with a longitudinal study in which the number of exposures over time to a single message like the admixture vignette is varied, and multiple racial belief, attitude, and behavioral-intention measures are assessed over time, allowing the researcher to track the progression (or lack thereof) from more proximal to more distal measures of racism, as well as the endurance of changes in the proximal belief measures, with repeated exposure to messages about race and genes. We thank an anonymous reviewer for this suggestion.

REFERENCES

- Allport Gordon W. The Nature of Prejudice. Doubleday; Garden City, NY: 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Angier Natalie. Do Races Differ? Not Really, Genes Show. New York Times. 2000 Aug 22;:1. Section F, Column 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Anan Yoav, Nosek Brian A. [Retrieved June 3, 2012];A Comparative Investigation of Seven Implicit Measures of Social Cognition. 2012 ( http://ssrn.com/abstract=2074556 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2074556)

- Bastian B, Haslam N. Psychological Essentialism and Stereotype Endorsement. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2006;42:228–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bolnick Deborah A., Fullwiley Duana, Duster Troy, Cooper Richard S., Fuji-mura Joan H., Kahn Jonathan, Kaufman Jay S., Marks Jonathan, Morning Ann, Nelson Alondra, Ossorio Pilar, Reardon Jenny, Reverby Susan M., TallBear Kimberly. The Science and Business of Genetic Ancestry Testing. Science. 2007;318:399–400. doi: 10.1126/science.1150098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer Marilynn B., Brown Rupert J. Intergroup Relations. In: Gilbert DT, Fiske ST, Lindzey G, editors. The Handbook of Social Psychology. 4th ed Vol. 2. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1998. pp. 554–94. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen Jacob. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Collins Francis. Introductory Remarks. Presented at A Decade of ELSI Research; Bethesda, MD. January 16–18.2001. [Google Scholar]

- Condit Celeste M., Bates B. How Lay People Respond to Messages about Genetics, Health and Race. Clinical Genetics. 2005;68:97–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2005.00480.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condit Celeste M., Parrott RL, Bates BR, Beyan J, Achter PJ. Exploration of the Impact of Messages about Genes and Race on Lay Attitudes. Clinical Genetics. 2004;66:402–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly Emma. DNA Tells Students They Aren’t Who They Thought. New York Times. 2005 Apr 13;:8. Section B, Column 3. [Google Scholar]

- DeBell Matthew, Krosnick Jon A., Lupia Arthur. Methodology Report and User’s Guide for the 2008–2009 ANES Panel Study. Stanford University and the University of Michigan; Palo Alto, CA, and Ann Arbor, MI: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Duster Troy. Backdoor to Eugenics. 2nd ed Routledge; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Duster Troy. The Molecular Reinscription of Race: Unanticipated Issues in Bio-technology and Forensic Science. Patterns of Prejudice. 2006;40:427–41. [Google Scholar]

- Fanon Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. Grove Press; New York: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Feagin Joe. Racist America: Roots, Current Realities, and Future Reparations. Routledge; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske Susan T., Taylor SE. Social Cognition: From Brains to Culture. McGraw Hill; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimura Joan H., Duster Troy, Rajagopalan Ramya. Introduction: Race, Genetics, and Disease: Questions of Evidence, Matters of Consequence. Social Studies of Science. 2009;38:643–56. doi: 10.1177/0306312708091926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullwiley Duana. The Molecularization of Race: Institutionalizing Human Difference in Pharmacogenetics Practice. Science as Culture. 2007;16:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Gates Henry Louis. Faces of America. Public Broadcasting System; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JLK. Measuring Individual Differences in Implicit Cognition: The Implicit Association Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1464–80. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.6.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henig Robin M. The Genome in Black and White (and Gray) New York Times. 2004 Oct 10;:47. Section 6, Column 1. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman Curt, Hurst Nancy. Gender Stereotypes: Perception or Rationalization? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1990;58:197–208. [Google Scholar]

- The International HapMap Consortium The International HapMap Project. Nature. 2003;426:789–96. doi: 10.1038/nature02168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller J. In Genes We Trust: The Biological Component of Psychological Essentialism and Its Relationship to Mechanisms of Motivated Social Cognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;88:686–702. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.88.4.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluegel James R. Trends in Whites’ Explanations of the Black-White Gap in Socioeconomic Status, 1977–1989. American Sociological Review. 1990;55:512–25. [Google Scholar]

- Leroi Armand M. A Family Tree in Every Gene. New York Times. 2005 Mar 14;:21. Section A, Column 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lindee M. Susan. Review of DNA: The Secret of Life by James D. Watson, with Andrew Berry. Knopf. Grain; New York: [Retrieved March 17, 2014]. 2003. ( http://www.grain.org/article/entries/426-dna-the-secret-of-life-by-james-d-watson-with-andrew-berry-new-york-knopf-2003) [Google Scholar]

- Link Bruce G., Phelan Jo C. Conceptualizing Stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–85. [Google Scholar]

- Lippman A. Led (Astray) by Genetic Maps: The Cartography of the Human Genome and Health Care. Social Science and Medicine. 1992;35:1469–76. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90049-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Carol Lynn, Parker Sandra. Folk Theories about Sex and Race Differences. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1995;21:45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas, Denton Nancy. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Harvard University Press; Cambridge: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Nelkin D, Lindee MS. The DNA Mystique: The Gene as a Cultural Icon. W.H. Freeman & Company; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson Alondra. Bio Science: Genetic Genealogy Testing and the Pursuit of African Ancestry. Social Studies of Science. 2008;38:759–83. doi: 10.1177/0306312708091929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson Alondra. [Retrieved March 17, 2014];Henry Louis Gates’s Extended Family. Chronicle of Higher Education. 2010 ( http://chronicle.com/article/Henry-Louis-Gat ess-Extended/64192/)

- Office of International information Programs, U.S. Department of State [Retrieved June 26, 2014];Transcript: White House Briefing on Genome Map. 2000 ( http://usinfo.state.gov)

- Oliver Melvin L., Shapiro Thomas M. Black Wealth/White Wealth: A New Perspective on Racial Inequality. Tenth Anniversary Edition Routledge; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Omi Michael, Winant Howard. Racial Formation in the United States: From the 1960s to the 1990s. 2nd ed Routledge; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Payne B. Keith, Cheng Clara Michelle, Govorun Alice, Stewart Brandon D. An Inkblot for Attitudes: Affect Misattribution as Implicit Measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2005;89:277–93. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.89.3.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center for the People and the Press [accessed January 6, 2013];2013 ( www.people-press-org/2012/27/in-changing-news-landscape-even-television-is-vulnerable/)

- Phelan Jo C., Link Bruce G., Feldman Naumi M. The Genomic Revolution and Beliefs about Essential Racial Differences: A Backdoor to Eugenics? American Sociological Review. 2013;78:167–91. doi: 10.1177/0003122413476034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart M, Taylor M. Category Labels and Social Reality: Do We View Social Categories as Natural Kinds? In: Semin GR, Fiedler K, editors. Language, Interaction and Social Cognition. Sage; London: 1992. pp. 13–36. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Charmaine D., Novembre John, Fullerton Stephanie M., Goldstein David B., Long Jeffrey C., Barnshad Michael J., Clark Andrew G. Inferring Genetic Ancestry: Opportunities, Challenges, and Implications. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2010;86:661–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin WG, editors. Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Nelson-Hall; Chicago: 1986. pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Telles EE. Race in Another America: The Significance of Skin Color in Brazil. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wade Nicholas. For Sale: A DNA Test to Measure Racial Mix. New York Times. 2002 Oct 1;:4. 2002, Section F, Column 5. [Google Scholar]

- Wade Nicholas. Articles Highlight Different Views on Genetic Basis of Race. New York Times. 2004 Oct 27;:13. Section A, Column 1. [Google Scholar]