Abstract

Assembly of many dsDNA viruses involves packaging of DNA molecules into pre-assembled procapsids by portal molecular motor complexes. Techniques have recently been developed using optical tweezers to directly measure the packaging of single DNA molecules into single procapsids in real time and the forces generated by the molecular motor. Three different viruses, phages phi29, lambda, and T4, have been studied, revealing interesting similarities and differences in packaging dynamics. Single-molecule fluorescence methods have also been used to measure packaging kinetics and motor conformations. Here we review recent discoveries made using these new techniques.

Many dsDNA viruses, including bacteriophages and human herpesviruses and adenoviruses, follow an unusual assembly pathway wherein an empty procapsid shell assembles first and DNA is packaged by ATP-powered portal motor [1–4]. Two major types of viral motors appear to have diverged long ago [5]. One, occurring in phage Phi29 and adenoviruses, belongs to the HerA/FtsK superfamily. A second, occurring in phages T4 and Lambda and herpesviruses, utilize a “terminase” enzyme to package genomes from a concatemeric substrate. In vitro packaging with purified components has been demonstrated in several systems, enabling detailed studies. A traditional approach for measuring packaging involves monitoring DNA protection from DNAase, but this method suffers from limited time resolution and lack of synchronization of complexes. Recent techniques for measuring single DNA molecule packaging have led to new insights.

Manipulation of single DNA molecules

“Optical tweezers” is a technique wherein a micron-sized plastic microsphere is trapped by a focused laser beam in an optical microscope [6–9]. Single DNA molecules can be manipulated by tethering their ends to microspheres [10–13]. When a trapped microsphere is displaced by an external force, the laser is deflected and exerts an opposing trapping force. In this manner, one can apply and measure piconewton-level forces and nanometer-level displacements.

Measuring single DNA packaging

Bacteriophage phi29 was the first system to be studied by this approach [14]. It is a small phage with a 19.3 kbp genome and 42 × 54 nm capsid. The motor consists of a dodacameric “connector” ring (gp10) attached to pentameric rings of RNA molecules and ATPases (gp16) [15].

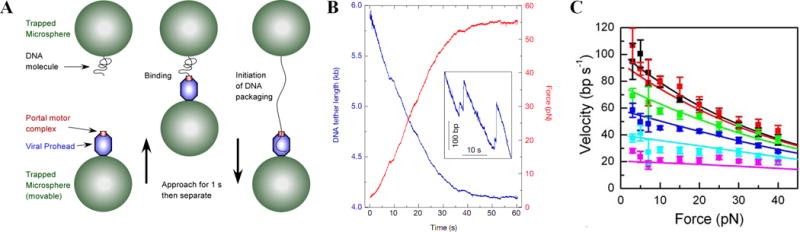

In the first approach, the DNA was end-labeled with biotin and packaging was initiated in bulk with purified procapsids, gp16, and DNA, and then stalled with a non-hydrolyzable ATP analog [14]. Complexes were tethered via the unpackaged DNA end to a streptavidin-coated microsphere, which was injected into a microfluidic chamber containing ATP. A second microsphere coated with anti-phi29 antibodies was injected and trapped with a second laser. The two microspheres were brought into proximity by steering one laser, allowing the procapsid to bind within seconds to the anti-phi29 microsphere. In a second approach (Fig. 1A), prohead-motor complexes are assembled and bound to one microsphere, and DNA is bound to a second microsphere [16]. When brought into proximity the motor binds the DNA and initiates packaging.

Fig. 1.

Measuring single DNA molecule packaging using optical tweezers [14,16]. (A) Phi29 procapsid-motor complexes are attached to antibody-coated microspheres and captured in a laser trap (bottom left). A microsphere carrying DNA was captured in a second laser trap (top left). To initiate DNA packaging, the microspheres are brought into near contact (middle) and then quickly separated to probe for DNA binding and translocation (right) [16]. (B) Unpackaged DNA length vs. time (blue) and force (red) as packaging proceeds with fixed trap positions [14]. Inset shows magnified section showing examples of occasional back-slipping events. (C) Average motor velocity vs. applied force for ATP concentrations of 500, 250, 100, 50, 25, and 10 μm (black/top, red, green, blue, cyan, and pink, respectively) (panel C reproduced with permission from Ref. [17]).

Native phi29 DNA has terminal proteins (gp3), a feature shared with adenoviruses. Surprisingly, in these measurements the initial DNA extension was found to be highly variable except when the gp3 was digested with proteinase K, suggesting that gp3 mediates DNA looping [16]. How such DNA loops could be resolved during packaging is an unsolved mystery.

Phi29 motor dynamics

When the motor reels the DNA into the procapsid the DNA is stretched between the two microspheres, exerting an increasing force on the motor (Fig. 1B). Measurement of the laser deflection allows translocation rate and force to be measured in real time. Strikingly, the motor was found to translocate DNA at rates up to 165 bp/s and exert forces as high as 65 pN, extrapolating to ~110 pN, making it one of the strongest known biological motors [14,16]. Skeletal muscle myosin motors, by comparison, exert only ~2 pN.

The initial motor velocity in saturating ATP (0.5 mM) decreases with increasing force (Fig. 1C). Increasing temperature from 20 to 35 °C also increases velocity by 2–3-fold (M. White and D. Smith, unpublished data). Packaging is highly processive, with short backward slips (typically only releasing at most hundreds of bp) occurring less than once per genome length. Studies of the dependence of motor velocity on force and ATP, ADP, and phosphate concentrations suggest that DNA translocation steps are tightly coupled to ATP hydrolysis and occur after ATP binding, hydrolysis, and phosphate release [17].

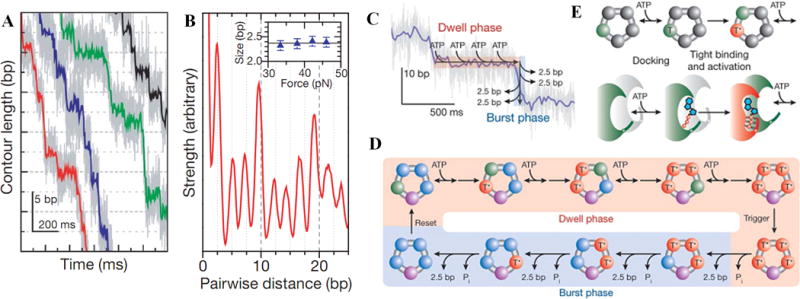

High-resolution measurements recently showed that packaging occurs in bursts of four 2.5 bp steps (Fig. 2A&B) [18]. The dwell time between bursts is dependent on ATP concentration, but the rate of stepping is not, suggesting that motor subunits are highly coordinated and four subunits bind ATP before a burst is triggered (Fig. 2C&D). The results suggest that a tight ATP binding transition of one motor subunit activates ATP binding by the next subunit (Fig. 2E). One of the five motor subunits is proposed to hold the DNA while the other four reload ATP.

Fig. 2.

(A) High-resolution measurements of DNA translocation vs. time, showing phi29 packaging occurs in bursts of ~2.5 bp steps [18]. (B) Pairwise distance correlation analysis indicates that the mean step size is 2.4 ± 0.1 bp. (C&D) Proposed model [18,19]: four motor subunits bind four ATP molecules, first loosely (T) then tightly (irreversibly)(T*), which triggers a burst of steps. (D&E) Each tight binding event activates the next subunit for binding and each translocation step occurs after hydrolysis and phosphate (Pi) release (all panels reproduced with permission from Ref. [18]).

Motor-DNA interactions

The observed non-integer 2.5 bp step size suggests that the motor doesn’t make repeated contacts with identical DNA moieties, but rather translocates it via steric interactions and step size dictated by conformational changes in the motor. Studies of the effect of DNA structure modifications provided additional insights [19]. When 10 “bp” sections of neutral methyl-phosphonate backbone were inserted into the DNA this usually caused the motor to pause but still traverse the insert. Increasing the insert size from 10 to 11 bp caused a sharp decrease in traversal, suggesting the motor tends to contact phosphate charges on both strands every 10 bp. However, inserts up to 30 bp could also be traversed, demonstrating that phosphate charge interactions are not required. Traversal probability was 10-fold lower when a neutral segment was placed on the 5′-3′ strand vs. 3′-5′, suggesting that phosphate contacts are mainly with the 5′-3′ strand. The motor also traversed single-stranded gaps, unpaired bulges, and synthetic polymer inserts with little resemblance to DNA, supporting the conclusion that translocation is mainly driven by non-specific steric interactions. An early model for the motor [20] proposed that the helical dsDNA may be translocated by rotation of the connector ring, analogous to a nut threading a bolt, but recent single-molecule fluorescence polarization measurements found no evidence for connector rotation, suggesting that phi29 ATPases drive translocation by ratcheting motions [21].

Forces resisting DNA confinement

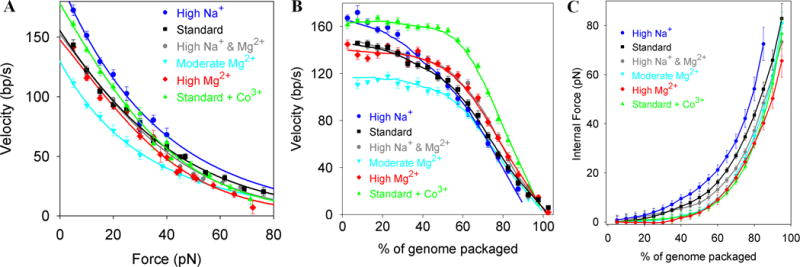

Measurements with a force-clamp and ramped stretching techniques show that the phi29 motor velocity slows as packaging proceeds [14,22]. This occurs because an “internal” force that resists dense DNA confinement in the procapsid builds and loads the motor. The force arises due to energetic penalties of confinement associated with increased DNA bending, electrostatic self-repulsion, and entropy loss [23]. By measuring the dependence of velocity on both force and filling the internal force vs. filling can be inferred (Fig. 3) [14,16]. It extrapolates to ~110 pN at 100% packaging.

Fig. 3.

(A) Average motor velocity vs. applied load force at low capsid filling in various ionic conditions [24]. (B) Average velocity vs. % of genome packaging at low force. (C) Internal force resisting DNA packaging inferred from (A&B).

Ionic conditions affect motor function and internal force separately (Fig. 3) [24]. Mg2+ (~1 mM) is needed for motor function, but adding 100 mM Na+ increases the unloaded motor velocity. Internal forces, however, are up to ~80% higher when Na+ is the dominant ion vs. Mg2+. The observed decrease in force with increasing ionic screening of DNA charge (Fig. 3C) confirms that electrostatic repulsion is a primary contributor to internal force.

The measured internal force vs. capsid filling is similar to that predicted by theoretical models using several different analytic and simulation approaches [25–27]. The analytic models assume inverse spooling of the DNA in a hexagonally packed lattice. Small discrepancies between theory and experiment [16,24] could be due to various effects, including inaccuracy in knowledge of capsid volume, less-ordered DNA packing geometry, and/or non-equilibrium or dissipative effects.

Phage lambda packaging

Lambda packaging required a different approach than phi29 because the lambda terminase motor complex (gpNu1 and gpA) binds to a specific DNA site, cleaves the DNA, and packages from that point [28]. Instead of assembling a prohead-motor complex, a motor-DNA complex was assembled and tethered to one microsphere and procapsids were bound to a second microsphere [29]. When the microspheres were brought into near contact in the presence of ATP the motor-DNA complex bound to the procapsid and began packaging.

Measurements showed that the motor, like that of phi29, exerts large force (> 50 pN), translocates with high processivity, and slows with increasing force. One striking difference was that it translocates ~3.5× faster, on average, than phi29. Since lambda’s genome is 2.5× longer than phi29’s, both took a similar time to complete packaging (~2–3 minutes). Lambda exhibited 3-fold less slipping than phi29, but 7-fold more pausing at high force. However since pauses were short (averaging ~2.5 seconds) they had only a minor effect on packaging rate. The cause of pauses is uncertain but they may be triggered by internal force fluctuations.

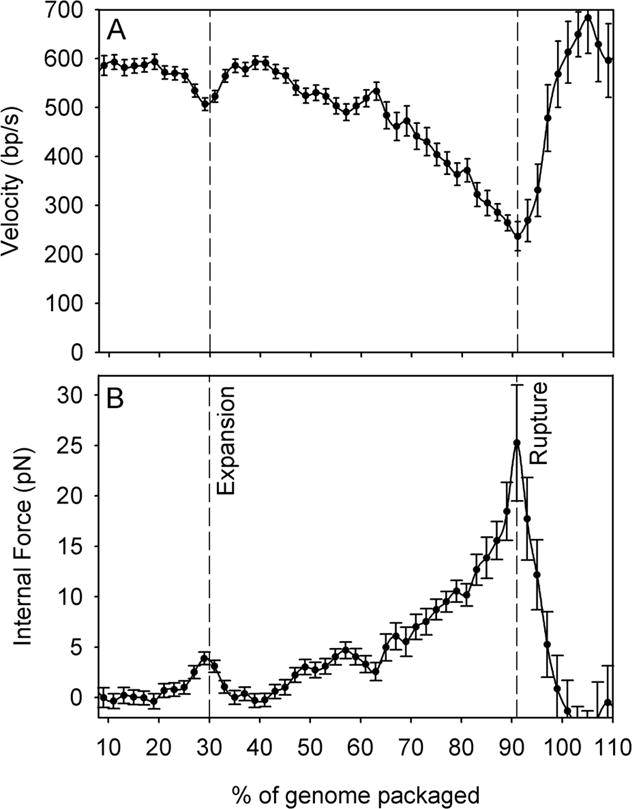

The dependence of the lambda motor velocity on capsid filling (Fig. 4A) showed distinct differences from the monotonic decrease observed with phi29. At 86% packaging the inferred internal force rose to ~14 pN, in excellent agreement with that predicted theoretically and deduced from experiments using osmotic pressure to suppress DNA ejection [25,30]. Notably, a distinct dip in motor velocity (decrease then increase) was observed at ~30% packaging [29] and the velocity abruptly increased beyond ~90% packaging. Interestingly, these events provide evidence supporting two longstanding hypotheses regarding capsid expansion and stability. A 2-fold expansion in capsid volume is known to occur somewhere between 10–50% packaging and hypothesized to be triggered by DNA pressure [31]. The observed dip in motor velocity at 30% implies a 4 pN increase then decrease in average internal force, consistent with expansion being driven by internal force (Fig. 4B). The increase in velocity beyond 90% is consistent with premature procapsid rupture due to lack of an accessory capsid protein (gpD) hypothesized to increase capsid strength [32–36]. Such features were not seen in phi29, which does not undergo capsid expansion and does rely on an accessory capsid protein.

Fig. 4.

(A) Lambda packaging rate vs. % of genome length packaged [29]. (B) Average internal force resisting packaging. Dashed lines indicate filling levels at which capsid expansion and rupture (in the absence of gpD) are inferred to occur.

Phage T4 packaging

T4 packaging has also recently been measured with optical tweezers and found to be driven by a very strong (>60 pN) and processive motor [37], suggesting these are universal properties all dsDNA viral motors need to package DNA to high density. Interestingly, packaging required only the large terminase subunit (gp17), indicating that this ATPase is responsible for force generation.

An especially striking feature of the T4 motor was its high speed, averaging ~700 bp/s and ranging up to ~2000 bp/s. As T4’s genome is ~9× longer than phi29’s and 3.5× longer than lambda’s, these measurements suggest that motor speeds scale with viral genome size. Such a trend may have evolved because of the limited 5–10 minute window during the infection-lysis cycle for packaging to occur [38]. The T4 motor generates a maximum power (average force × velocity) of 5.2 × 10−18 Watts; a small number, but the power density is ~5,000 kW/m3, about twice that generated by a car engine.

Surprisingly, average velocities of individual T4 motors ranged from 70 bp/s to 1840 bp/s with a standard deviation equal to 40% of the mean velocity. The phi29 and lambda motor velocities varied less (by ~10% and 20%). Individual T4 motors also exhibited velocity changes in time ranging as wide as 500 to 1500 bp/s, too large to be reconciled by standard biochemical kinetic models. This suggests that individual motors can adopt different conformational states gearing different DNA translocation rates.

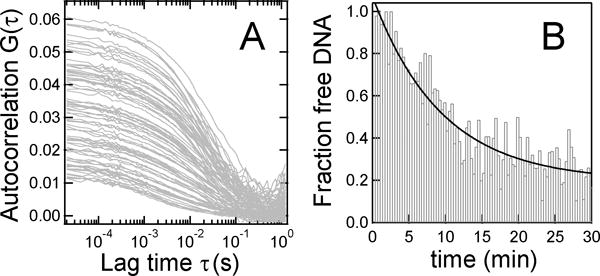

Single-molecule fluorescence techniques have been recently applied to measure T4 packaging [39–43]. In fluctuation correlation spectroscopy (FCS) a focused laser illuminated a microscopic volume and fluorescent-labeled DNAs diffuse in and out, producing bursts of fluorescence. Time correlation analysis yields information on diffusion coefficients, which increase when the DNA is packaged into the much larger procapsids (Fig. 5). Using this method, it was shown that multiple short 100 bp DNAs can be sequentially packaged [39] and a single nick in 100–200 bp DNAs sharply reduces packaging and motor-DNA affinity [40].

Fig 5.

Phage T4 DNA packaging kinetics measured by fluctuation correlation spectroscopy (A) The autocorrelation function, acquired every 20 s, increases steadily as labeled DNA is packaged. (B) Unpackaged DNA vs. time determined from (A). Reproduced with permission from Ref. [39].

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET), which detects proximity of two dye-labeled species, was further used to demonstrate that the ends of 5 and 50 kbp DNAs co-localized within 8–9 nm after being packaged in T4, suggesting that a DNA loop, rather than single end, might be translocated by the motor [42]. While surprising given apparent constraints on portal diameter, this could explain how phi29 DNA loops [16] could be packaged.

Studies have also examined the stalling of T4 motors at a Y-junction placed in the dsDNA [42,43]. FRET signals between pairs of labels placed on the Y-junction, leading DNA, portal ring, and/or terminase proteins suggest that conformational changes occur in both the DNA substrate and motor proteins during packaging, consistent with a proposed linear grip-and-release compression mechanism [43].

Motor structure-function relationships

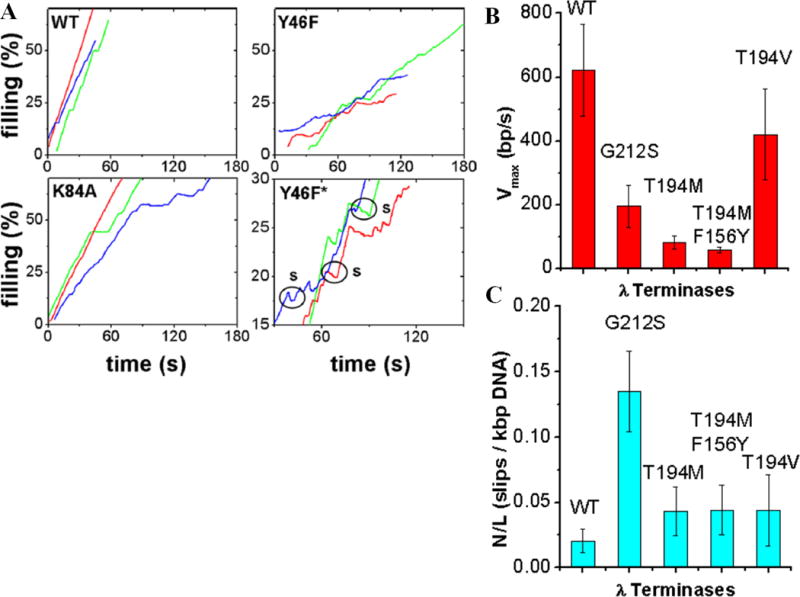

Progress has recently been made in characterizing lambda mutants having altered packaging dynamics in great detail by single-molecule measurements [44,45]. A structural model for lambda gpA has been proposed based on sequence and structural homologies with T4 gp17 [46–52]. The model identifies elements common to AAA+ ATPases (Walker A and Walker B motifs, a switch residue, and a catalytic carboxylate) and two motifs discovered in helicases important for mechanochemical coupling (an adenine-binding “Q-motif” and a “coupling” C-motif) [47].

gpA has a predicted Walker A-like motif at 76-KSARVGYS-83. Amino acid change K84A, adjacent to this region, decreased motor velocity by ~40% without altering processivity or steepness of the velocity-force dependence (Fig. 6). This supports the hypothesis that Walker A is involved in ATP binding, but not coupling, and that ATP binding and hydrolysis precede the force-generating steps.

Fig. 6.

Effects on phage lambda packaging dynamics of mutations altering the large terminase subunit (gpA) [44,45]. (A) Typical recordings of % of genome length packaged vs. time for wildtype (WT), Y46F (change in the putative Q motif), and K84A (change adjacent the putative Walker A motif). Panel labeled “Y46F*” is a zoomed view illustrating frequent motor slipping (labeled “s”). (B) Average motor velocity and (C) slipping frequency for WT, G212S (change in the putative C-motif), T194M (change in the loop-helix-loop region), T194M/F156Y double mutant, and T194V pseudo-revertant.

gpA has a predicted Q-motif at 46-YQ-47. Studies of RNA helicases suggest this motif regulates nucleic acid affinity and conformational changes driven by nucleotide hydrolysis [53]. Consistent with this, optical tweezers measurements showed that mutation Y46F in gpA decreased motor velocity 40% and increased slipping by >10-fold [44]. Velocity also decreased more steeply with increasing force, indicating that the Q-motif also regulates motor power. Change G212S in the predicted lambda C-motif caused a 3-fold decrease in velocity and a 6-fold reduction in processivity, also consistent with a coupling defect.

Random screens further identified mutants with changes in a region of gpA outside any known motifs exhibiting altered packaging [54]. Optical tweezers measurements showed that change T194M caused a 8-fold reduction in motor velocity without changing processivity or force dependence [45]. Structural modeling indicates that T194 is part of a loop-helix-loop region that connects the Walker B and C-motifs. The related SpoIIIE bacterial chromosome segregation motor is predicted to have an analogous region and change D584A in that region reduced DNA translocation rate ~3-fold [55]. Together, these findings suggest that this may be a conserved structural region that governs motor velocity.

Conclusions

Single-molecule optical tweezers and fluorescence methods have shed new light on viral packaging motor function, mechanism, and forces resisting DNA confinement. Some interesting future directions include:

- Extending studies of the effect of mutations altering packaging motor residues to further establish structure function relationships.

- Extending high-resolution optical tweezers measurements to systems besides phi29, to investigate whether the bursts-of-translocation-steps mechanism is universal.

- Studying how physiologically relevant polyamines, such as spermidine and spermine, and host and viral DNA binding proteins affect DNA packaging.

- Studying whether packaging forces equilibrate rapidly during packaging, or whether non-equilibrium and/or dissipative effects may increase the energy needed for packaging.

- Developing approaches using single molecule techniques to study mechanisms of initiation and termination of packaging.

- Extending the single molecule methods to other virus systems of interest that utilize packaging motors, such as human herpesviruses and adenoviruses.

Acknowledgments

I thank many colleagues for advice and assistance, including A. Davenport, D. del Toro, D. Fuller, D. Raymer, J.P. Rickgauer, J. Tsay, C. Bustamante, S. Smith, S. Tans, D. Anderson, S. Grimes, P. Jardine, C. Catalano, M. Feiss, J. Sippy, B. Draper, V. Kottadiel, V. Rao, K. Aathavan, Y. Chemla, C. Hetherington, J. Michaelis, J. Moffitt, W. Gelbart, P. Grayson, P. Purohit, and R. Phillips. I thank Burroughs Wellcome Fund, Beckman Foundation, Kinship Foundation, NIH, and NSF for support.

References

- 1.Rao VB, Feiss M. The Bacteriophage DNA Packaging Motor. Annu Rev Genet. 2008;42:647–681. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.42.110807.091545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catalano CE, editor. Viral Genome Packaging Machines: Genetics, Structure, and Mechanism. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jardine PJ, Anderson DL. DNA packaging in double-stranded DNA bacteriophages. In: Calendar R, editor. The Bacteriophages. Vol. 2006. Oxford Press; p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao VB, Black LW. Bacteriophage T4 DNA Packaging. In: Catalano CE, editor. Viral Genome Packaging Machines: Genetics, Structure and Mechanism. Landes Biosciences; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iyer LM, Leipe DD, Koonin EV, Aravind L. Evolutionary history and higher order classification of AAA+ ATPases. J Struct Biol. 2004;146:11–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2003.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashkin A, Dziedzic JM, Bjorkholm JE, Chu S. Observation of a single-beam gradient force optical trap for dielectric particles. Opt Lett. 1986;11:288–290. doi: 10.1364/ol.11.000288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neuman KC, Block SM. Optical trapping. Rev Sci Instrum. 2004;75:2787–809. doi: 10.1063/1.1785844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moffitt JR, Chemla YR, Smith SB, Bustamante C. Recent advances in optical tweezers. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:205–28. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.043007.090225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perkins TT. Optical Traps for Single Molecule Biophysics: a primer. Laser & Phontonics Reviews. 2009;3:203. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perkins TT, Quake SR, Smith DE, Chu S. Relaxation of a single DNA molecule observed by optical microscopy. Science. 1994;264:822–826. doi: 10.1126/science.8171336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith SB, Cui Y, Bustamante C. Overstretching B-DNA: the elastic response of individual double-stranded and single-stranded DNA molecules. Science. 1996;271:795–799. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5250.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bustamante C, Smith SB, Liphardt J, Smith D. Single-molecule studies of DNA mechanics. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2000;10:279–285. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00085-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fuller DN, Gemmen GJ, Rickgauer JP, Dupont A, Millin R, Recouvreux P, Smith DE. A general method for manipulating DNA sequences from any organism with optical tweezers. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:e15. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnj016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith DE, Tans SJ, Smith SB, Grimes S, Anderson DL, Bustamante C. The bacteriophage phi29 portal motor can package DNA against a large internal force. Nature. 2001;413:748–752. doi: 10.1038/35099581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grimes S, Jardine PJ, Anderson D. Bacteriophage phi 29 DNA packaging. Adv Virus Res. 2002;58:255–294. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(02)58007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rickgauer JP, Fuller DN, Grimes S, Jardine PJ, Anderson DL, Smith DE. Portal motor velocity and internal force resisting viral DNA packaging in bacteriophage phi29. Biophys J. 2008;94:159–167. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.104612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chemla YR, Aathavan K, Michaelis J, Grimes S, Jardine PJ, Anderson DL, Bustamante C. Mechanism of force generation of a viral DNA packaging motor. Cell. 2005;122:683–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18**.Moffitt JR, Chemla YR, Aathavan K, Grimes S, Jardine PJ, Anderson DL, Bustamante C. Intersubunit coordination in a homomeric ring ATPase. Nature. 2009;457:446–450. doi: 10.1038/nature07637. Direct high-resolution measurement of bursts of 2.5 bp steps of the phi29 packaging motor, leading to a model for motor kinetics. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19*.Aathavan K, Politzer AT, Kaplan A, Moffitt JR, Chemla YR, Grimes S, Jardine PJ, Anderson DL, Bustamante C. Substrate interactions and promiscuity in a viral DNA packaging motor. Nature. 2009;461:669–673. doi: 10.1038/nature08443. New insights of the nature of motor-DNA interactions from studies of the dynamics of packaging of DNA templates with inserts containing structural modifications. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hendrix RW. Symmetry mismatch and DNA packaging in large bacteriophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75:4779–83. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.10.4779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hugel T, Michaelis J, Hetherington CL, Jardine PJ, Grimes S, Walter JM, Falk W, Anderson DL, Bustamante C. Experimental test of connector rotation during DNA packaging into bacteriophage phi29 capsids. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e59. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rickgauer JP, Smith DE. Single-Molecule Studies of DNA Visualization and Manipulation of Individual DNA Molecules with Fluorescence Microscopy and Optical Tweezers. In: Borsali R, Pecora R, editors. Soft Matter: Scattering, Imaging And Manipulation. Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riemer SC, Bloomfield VA. Packaging of Dna in Bacteriophage Heads – some Considerations on Energetics. Biopolymers. 1978;17:785–794. doi: 10.1002/bip.1978.360170317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24*.Fuller DN, Rickgauer JP, Jardine PJ, Grimes S, Anderson DL, Smith DE. Ionic effects on viral DNA packaging and portal motor function in bacteriophage phi 29. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:11245–11250. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701323104. Characterization of the dependence of internal force resisting genome packaging on ionic screening of DNA charge, demonstrating the importance of electrostatic self-repulsion of DNA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tzlil S, Kindt JT, Gelbart WM, Ben-Shaul A. Forces and pressures in DNA packaging and release from viral capsids. Biophys J. 2003;84:1616–1627. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74971-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Purohit PK, Inamdar MM, Grayson PD, Squires TM, Kondev J, Phillips R. Forces during bacteriophage DNA packaging and ejection. Biophys J. 2005;88:851–866. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.047134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Petrov AS, Harvey SC. Packaging double-helical DNA into viral capsids: Structures, forces, and energetics. Biophys J. 2008;95:497–502. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.131797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feiss M, Catalano C. Bacteriophage lambda terminase and the mechanism of viral DNA packaging. In: Catalano C, editor. Viral genome packaging machines: Genetics, structure and mechanism. Landes Bioscience; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29**.Fuller DN, Raymer DM, Rickgauer JP, Robertson RM, Catalano CE, Anderson DL, Grimes S, Smith DE. Measurements of single DNA molecule packaging dynamics in bacteriophage lambda reveal high forces, high motor processivity, and capsid transformations. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:1113–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.09.011. Extension of the single-molecule optical tweezers approach to measure phage lambda packaging yielded new insights on motor function and the nature of capsid expansion and rupture. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evilevitch A, Castelnovo M, Knobler CM, Gelbart WM. Measuring the force ejecting DNA from phage. J Phys Chem B. 2004;108:6838–6843. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dokland T, Murialdo H. Structural transitions during maturation of bacteriophage lambda capsids. J Mol Biol. 1993;233:682–694. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sternberg N, Weisberg R. Packaging of coliphage lambda DNA. II The role of the gene D protein. J Mol Biol. 1977;117:733–759. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(77)90067-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perucchetti R, Parris W, Becker A, Gold M. Late stages in bacteriophage lambda head morphogenesis: in vitro studies on the action of the bacteriophage lambda D-gene and W-gene products. Virology. 1988;165:103–114. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gaussier H, Yang O, Catalano CE. Building a virus from scratch: Assembly of an infectious virus using purified components in a rigorously defined biochemical assay system. J Mol Biol. 2006;357:1154–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lander GC, Evilevitch A, Jeembaeva M, Potter CS, Carragher B, Johnson JE. Bacteriophage lambda stabilization by auxiliary protein gpD: timing, location, and mechanism of attachment determined by cryo-EM. Structure. 2008;16:1399–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang Q, Maluf NK, Catalano CE. Packaging of a Unit-Length Viral Genome: The Role of Nucleotides and the gpD Decoration Protein in Stable Nucleocapsid Assembly in Bacteriophage lambda. J Mol Biol. 2008;383:1037–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37*.Fuller DN, Raymer DM, Kottadiel VI, Rao VB, Smith DE. Single phage T4 DNA packaging motors exhibit barge force generation, high velocity, and dynamic variability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16868–16873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704008104. Extension of the single-molecule optical tweezers approach to measure phage T4 packaging reveals ultra-high-speed DNA translocation and variability in the dynamics of individual motors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mosig G, Eiserling F. T4 and related phages: structure and development. In: Calendar RL, editor. The Bacteriophages. Oxford Univ Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sabanayagam CR, Oram M, Lakowicz JR, Black LW. Viral DNA packaging studied by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Biophys J. 2007;93:L17–9. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.111526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oram M, Sabanayagam C, Black LW. Modulation of the packaging reaction of bacteriophage t4 terminase by DNA structure. J Mol Biol. 2008;381:61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.05.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ray K, Sabanayagam CR, Lakowicz JR, Black LW. DNA crunching by a viral packaging motor: Compression of a procapsid-portal stalled Y-DNA substrate. Virology. 2010;398:224–232. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.11.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ray K, Ma J, Oram M, Lakowicz JR, Black LW. Single-molecule and FRET fluorescence correlation spectroscopy analyses of phage DNA packaging: colocalization of packaged phage T4 DNA ends within the capsid. J Mol Biol. 2010;395:1102–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.11.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43*.Dixit A, Ray K, Lakowicz JR, Black LW. Dynamics of the T4 bacteriophage DNAa packasome motor: endo VII resolvase release of arrested Y-DNA substrates. J Biol Chem. 2011 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.222828. Novel evidence from fluorescence energy transfer measurements for conformational changes in both the DNA and motor during T4 packaging. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44*.Tsay JM, Sippy J, Feiss M, Smith DE. The Q motif of a viral packaging motor governs its force generation and communicates ATP recognition to DNA interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14355–14360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904364106. Insights on motor structure-function relationships from studies of the effect of mutations altering the large terminase subunit of the lambda packaging motor. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsay JM, Sippy J, DelToro D, Andrews BT, Draper B, Rao V, Catalano CE, Feiss M, Smith DE. Mutations altering a structurally conserved loop-helix-loop region of a viral packaging motor change DNA translocation velocity and processivity. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:24282–24289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.129395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Draper B, Rao VB. An ATP hydrolysis sensor in the DNA packaging motor from bacteriophage T4 suggests an inchworm-type translocation mechanism. J Mol Biol. 2007;369:79–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kondabagil KR, Zhang Z, Rao VB. The DNA translocating ATPase of bacteriophage T4 packaging motor. J Mol Biol. 2006;363:486–499. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mitchell MS, Rao VB. Functional analysis of the bacteriophage T4 DNA-packaging ATPase motor. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:518–527. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507719200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mitchell MS, Matsuzaki S, Imai S, Rao VB. Sequence analysis of bacteriophage T4 DNA packaging/terminase genes 16 and 17 reveals a common ATPase center in the large subunit of viral terminases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:4009–4021. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mitchell MS, Rao VB. Novel and deviant Walker A ATP-binding motifs in bacteriophage large terminase-DNA packaging proteins. Virology. 2004;321:217–221. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sun S, Kondabagil K, Draper B, Alam TI, Bowman VD, Zhang Z, Hegde S, Fokine A, Rossmann MG, Rao VB. The Structure of the Phage T4 DNA Packaging Motor Suggests a Mechanism Dependent on Electrostatic Forces. Cell. 2008;135:1251–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun S, Kondabagil K, Gentz PM, Rossmann MG, Rao VB. The structure of the ATPase that powers DNA packaging into bacteriophage t4 procapsids. Mol Cell. 2007;25:943–949. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cordin O, Tanner NK, Doere M, Linder P, Banroques J. The newly discovered Q motif of DEAD-box RNA helicases regulates RNA-binding and helicase activity. EMBO J. 2004;23:2478–2487. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Duffy C, Feiss M. The large subunit of bacteriophage lambda’s terminase plays a role in DNA translocation and packaging termination. J Mol Biol. 2002;316:547–561. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Burton BM, Marquis KA, Sullivan NL, Rapoport TA, Rudner DZ. The ATPase SpoIIIE transports DNA across fused septal membranes during sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Cell. 2007;131:1301–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]