Abstract

Epithelial barrier dysfunction has been implicated as one of the major contributors to the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. The increase in intestinal permeability allows the translocation of luminal antigens across the intestinal epithelium, leading to the exacerbation of colitis. Thus, therapies targeted at specifically restoring tight junction barrier function are thought to have great potential as an alternative or supplement to immunology-based therapies. In this study, we screened Bifidobacterium, Enterococcus, and Lactobacillus species for beneficial microbes to strengthen the intestinal epithelial barrier, using the human intestinal epithelial cell line (Caco-2) in an in vitro assay. Some Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus species prevented epithelial barrier disruption induced by TNF-α, as assessed by measuring the transepithelial electrical resistance (TER). Furthermore, live Bifidobacterium species promoted wound repair in Caco-2 cell monolayers treated with TNF-α for 48 h. Time course 1H-NMR-based metabonomics of the culture supernatant revealed markedly enhanced production of acetate after 12 hours of coincubation of B. bifidum and Caco-2. An increase in TER was observed by the administration of acetate to TNF-α-treated Caco-2 monolayers. Interestingly, acetate-induced TER-enhancing effect in the coculture of B. bifidum and Caco-2 cells depends on the differentiation stage of the intestinal epithelial cells. These results suggest that Bifidobacterium species enhance intestinal epithelial barrier function via metabolites such as acetate.

Keywords: 1H-NMR, intestinal epithelial permeability, metabonomics, probiotics, tight junctions

Introduction

The intestinal mucosa is the dividing line between the internal and external environment, and is continuously exposed to various innocuous and noxious substances in the intestinal lumen. The intestinal epithelium is a single layer of columnar intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) that forms a physical and functional barrier preventing intestinal penetration of unwanted antigens. For the maintenance of epithelial barrier integrity, IECs are tightly bound together by intercellular junctional complexes localized at the apical-lateral membrane and along the lateral membrane (Van Itallie and Anderson 2006). The intercellular junctional complexes consist of the tight junctions (TJ), gap junctions (GJ), adherence junctions (AJ), and desmosome (Tsukita and Furuse 2002; Groschwitz and Hogan 2009; Marchiand et al. 2010). In particular, the apical junctional complex, encompassing the TJ (composed of claudins and occludin) and AJ (containing E-cadherin), plays a crucial role in regulating epithelial barrier functions (Laukoetter et al. 2006).

Intestinal permeability reflects the state of the epithelial TJ (Van Itallie and Anderson 2006). The TJ seals the intercellular space between adjacent epithelial cells, and is responsible for regulating selective paracellular transport of ions and solutes (e.g., nutrients) and preventing the translocation of microorganisms (both commensals and pathogens) and antigens (including bacterial toxins and food components) across the epithelium (Tsukita and Furuse 2002; Balda and Matter 2008). However, some pathogens (e.g., Salmonella spp.) impair or subvert the intestinal epithelial TJ barrier, and subsequently cause acute inflammation (O'Hara and Buret 2008). Moreover, chronic inflammation is often associated with defective intestinal epithelial TJ barrier function that allows luminal antigens to stimulate underlying immune cells in various diseases (including celiac disease, Crohn's disease, diabetes, and food allergy) (Vogelsang et al. 1998; Suenaert et al. 2002; Ventura et al. 2006).

Intestinal permeability is affected by multiple factors including cytokines (notably TNF-α and IFN-γ), epithelial apoptosis, and exogenous factors (including alcohol, high-fat diet, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs) (Ferrier et al. 2006; Ma et al. 2006, 2008; Oshima et al. 2008; Groschwitz and Hogan 2009). Cytokine-mediated dysregulation of intestinal barrier function has been implicated as an etiological factor for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and numerous autoimmune diseases (Visser et al. 2009; Maloy and Powrie 2011). Especially in Crohn's disease, where TNF-α is thought to be a critical determinant of the predisposition to intestinal inflammation and a defective epithelial TJ barrier because treatment with anti-TNF-α antibodies improved impaired intestinal barrier function in Crohn's disease patients (Targan et al. 1997; Van Deventer 1997; Noth et al. 2012). TNF-α is known to be not only a proinflammatory cytokine that activates the endogenous inflammatory cascade but also a highly potent inducer of epithelial TJ disruption (Ma et al. 2005; Ye et al. 2006; He et al. 2012). The TNF-α-induced increase in intestinal TJ permeability is associated with downregulation of zonula occludens 1 (ZO-1) protein expression and an increase in myosin light chain kinase (MLCK)-mediated opening of the intestinal epithelial TJ barrier in a NF-κB-dependent manner.

Bifidobacterium species, Enterococcus species, Escherichia coli, Lactobacillus species, Streptococcus species, and Lactococcus lactis, most of which were originally isolated from healthy humans, have been used as probiotics to confer benefits to the host (De Vrese and Schrezenmeir 2008). Some of these probiotics have been shown to promote intestinal epithelial barrier integrity via modulation of the TJ in a strain-dependent manner (Miyauchi et al. 2012; Sultana et al. 2013). Numerous previous studies showed that pretreatment of human intestinal epithelial cell lines (specifically Caco-2, HT-29, and T-84) or animal models of colitis with probiotic bacteria confers protective effects against TJ barrier impairment induced by various factors, including pathogen infection, proinflammatory cytokines, and oxidative stress (Resta-Lenert and Barrett 2003, 2006; Ewaschuk et al. 2008; Ohland and MacNaughton 2010). These TJ-strengthening probiotics upregulated the expression of TJ proteins (notably occludin and ZO-1) or downregulated the expression of the pore-forming protein claudin-2, suggesting that probiotics directly regulate TJ barrier function at the gene expression level (Resta-Lenert and Barrett 2003; Ewaschuk et al. 2008). Furthermore, probiotics modulated various protein kinase signaling pathways, which enhanced phosphorylation of TJ proteins, which can either promote TJ formation and barrier function or alternatively promote TJ protein redistribution and complex destabilization (Resta-Lenert and Barrett 2003; Zyrek et al. 2007). However, the bacterial components and metabolites responsible for the TJ-strengthening effects have not yet been fully clarified.

Although protective effects on TJ integrity against harmful stimuli by pretreatment with probiotics have been well characterized as described above, there are only a limited number of studies focusing on the therapeutic effects of probiotics on impaired epithelial barrier function. In this study, we screened for beneficial microbes that promote the restoration of the intestinal epithelial barrier function under inflammatory conditions from intestinal microorganisms including Bifidobacterium, Enterococcus, and Lactobacillus species originating from human feces. The aim of this study was to investigate the mechanisms underlying the therapeutic effects of the screened bacteria. Furthermore, we tried to identify candidate metabolites responsible for the TJ-strengthening effects using 1H-NMR-based metabonomics.

Materials and Methods

Caco-2 cell culture

The human colonic adenocarcinoma epithelial cell line Caco-2 was obtained from Riken Cell Bank (Ibaraki, Japan) and kept in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. Caco-2 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM)-High glucose (Wako, Osaka, Japan) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated (30 min, 56°C) fetal bovine serum (Biowest, Nuaillé, France), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 1% nonessential amino acids (NEAA) (Wako). In this study, Caco-2 cells were used between passages 25 and 40. Cells cultivated to 80% confluence were seeded on 12-well Transwell® inserts (1.12 cm2 polycarbonate membrane with 0.4 μm pore size; Corning Life Sciences, Corning, NY) at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well. The culture medium was changed every 2 days until 20 days later when full polarization of the Caco-2 cell monolayer was achieved. The integrity of the Caco-2 cell monolayer was evaluated by measuring the transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) using a milicell-ERS (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The TER values measured in the experiments were summarized as table form below each figure, and all the figures were expressed as the relative TER value compared to the value before experimental treatment.

Bacterial isolates and sample preparation

Thirty bacterial isolates from human feces were used in this study (Table1). Each bacterial isolate was identified based on a nearly full 16S rRNA sequence, which was deposited in DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ). All bacterial strains were cultured in Difco Lactobacilli MRS (de Man-Rogosa Sharpe) broth (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) at 37°C under anaerobic conditions. Heat-killed bacteria were prepared by heating bacteria at 95°C for 10 min.

Table 1.

List of bacterial isolates used in this study

| Strain | Accession number |

|---|---|

| Lactobacillus | |

| L. salivarius WU 30 | AB932525 |

| L. fermentum WU 30 | AB932548 |

| L. fermentum WU 33 | AB932537 |

| L. gasseri WU 04 | AB932527 |

| L. gasseri WU 06 | AB932530 |

| L. rhamnosus WU 08 | AB932536 |

| L. gasseri WU 11 | AB932519 |

| L. pantheris WU 61 | AB932532 |

| L. pantheris WU 21 | AB932522 |

| L. rhamnosus WU 07 | AB932535 |

| L. rhamnosus WU 09 | AB932547 |

| L. rhamnosus WU 12 | AB932520 |

| L. rhamnosus WU 14 | AB932521 |

| L. salivarius WU 57 | AB932528 |

| L. salivarius WU 60 | AB932531 |

| L. salivarius WU 63 | AB932533 |

| Enterococcus | |

| E. cecorum WU 65 | AB932534 |

| E. faecium WU 31 | AB932549 |

| E. avium WU 58 | AB932529 |

| E. avium WU 22 | AB932523 |

| E. avium WU 76 | AB932546 |

| E. raffinosus WU 27 | AB932524 |

| Bifidobacterium | |

| B. bifidum WU 11 | AB932538 |

| B. bifidum WU 12 | AB932539 |

| B. bifidum WU 20 | AB932541 |

| B. bifidum WU 57 | AB932544 |

| B. longum WU 16 | AB932540 |

| B. longum WU 35 | AB932543 |

| B. adolescentis WU 22 | AB932542 |

| B. pseudocatenulatum WU 06 | AB932550 |

Evaluation of the TJ-barrier-strengthening ability of bacterial isolates

To screen the TJ-barrier-strengthening bacteria, polarized Caco-2 cell monolayers were exposed to bacterial isolates. On day 18 of cultivation, both apical and basal compartments of Caco-2 cell monolayers were washed twice with prewarmed PBS and then fresh DMEM without antibiotics added to both compartments of the Transwell® cell culture system. On day 20, the TER of each well was measured using a milicell-ERS. Caco-2 cell monolayers with >650 Ω cm2 of TER were used for further experiments. After the measurement of TER, the apical compartment of Caco-2 cell monolayers was washed with prewarmed PBS, and then the bacterial suspensions were exposed to the apical side at a multiplicity of infection (MOI, ratio of bacteria number to epithelial cell number) of 1 in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. Culture medium alone was used as a negative control. After 24 h incubation, the TER value was measured to assess epithelial TJ permeability. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Evaluation of preventive effect of bacterial isolates on TNF-α-induced impairment of TJ permeability

In the prevention screening, Caco-2 cell monolayers were washed with prewarmed PBS and then bacteria (MOI of 1) added to the apical compartment one hour before TNF-α treatment. Next, the Caco-2 cell monolayers were treated with TNF-α (20 ng/mL) from the basolateral compartment to induce TJ dysfunction and incubated for a further 23 h. The TER value was measured to assess epithelial barrier function after a total of 24 h incubation. The TNF-α treated group without bacteria was used as a negative control. The prevention effect was estimated by the change in TER compared with the value before bacteria was added. All experiments except for B. bifidum WU57 were performed in triplicate. The assay of B. bifidum WU57 was performed in duplicate.

Evaluation of restorative effect of bacterial isolates on TNF-α-induced impairment of TJ permeability

Fully polarized Caco-2 cell monolayers were washed with prewarmed PBS then antibiotic-free DMEM containing TNF-α was added to the basolateral compartment. After 48 h incubation, the Caco-2 cell monolayers were washed on both the apical and basolateral sides with prewarmed PBS. Subsequently, the apical compartment of the Caco-2 cell monolayers was exposed to the bacterial suspensions at a MOI of 1. After 24 h incubation, the TER value was measured to assess the restoration of TJ function. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

RNA isolation and Gene expression analysis

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the RNA concentration determined by absorbance at 260/280 nm using a spectrophotometer (nano-Drop ND-1000; Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE). For mRNA expression analysis, cDNA was prepared from 1500 to 2000 ng of total RNA using the High-Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The reverse transcription reactions were performed in a thermo cycler (iCycler, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) at 25°C for 10 min, 37°C for 120 min, and 85°C for 5 min. Real-Time PCR was performed with a StepOnePlus™ Real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) using the TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays No. Hs00268480_m1 (ZO-1), Hs00170162_m1 (occludin), Hs00221623_m1 (claudin-1), Hs00170423_m1 (E-cadherin), and Hs99999905_m1 (GAPDH) with TaqMan gene expression master mix according to the manufacturer's instructions (Applied Biosystems). The time-dependent TJ gene expression analysis during the coculture of B. bifidum WU12 and Caco-2 cells were repeated two independent times, each performed in duplicate or triplicate. The endpoint TJ gene expression analysis of Caco-2 cells treated with B. bifidum WU12 or acetate for 24 h were repeated three independent times, each performed in triplicate.

Characterization of metabolites in culture supernatants using 1H-NMR spectroscopy

Supernatants of B. bifidum monocultures and the coculture of TNF-α-treated Caco-2 cells and B. bifidum were collected at 6, 12, and 24 h. DMEM and the culture supernatants of Caco-2 cell monolayers treated with TNF-α for 48 h were also prepared. The metabolic profile of the culture supernatant was analyzed using a NMR spectrometer. The NMR samples were prepared by mixing with 10 mmol/L sodium 2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate (DSS) dissolved in deuterium oxide (D2O) and then transferred into 5 mm NMR tubes. The spectra of these supernatant samples were obtained on a Bruker DRU-700 spectrometer equipped with an inverse (proton coils closest to the sample) gradient 5 mm cryogenically cooled 1H/13C/15N probe (Bruker Biospin, Rheinstetten, Germany), operating at 700.15 MHz for protons. The NMR measurement and data analysis of Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill (CPMG) pulse sequences was performed as per previous studies (Date et al. 2012). The spectra acquired at 298 K, and 32,768 data point with a spectral width of 12,500 Hz were collected into 32 transients and 16 dummy scans. The NMR spectra were processed using TopSpin 3.1 software (Bruker Biospin) and assigned using the SpinAssign programs at the PRIMe web site (http://prime.psc.riken.jp/) (Chikayama et al. 2010). The CPMG spectra data were reduced by subdividing spectra into sequential 0.04 ppm-designated regions between 1H chemical shifts of −0.5 to 9.0 ppm. After exclusion of water resonance (4.7–5.0 ppm), each region was integrated and normalized to the total of DSS integral regions. The normalized spectra data were statistically evaluated by Principle Component Analysis (PCA) using the ‘R (2.15.2)’ software.

Determination of acetate, formate, and lactate in culture supernatants

Supernatant samples were treated with an equal volume of acetonitrile (Wako) at room temperature to precipitate proteins, and then centrifuged for 10 min at 20,000 × g at room temperature. The supernatant was collected by filtration through a 0.2 μm Advantec® disposable membrane filter unit (Toyo Roshi, Tokyo, Japan) and then stored at −80°C until analysis. Samples were diluted 100-fold in ddH2O on the eve of analysis. Acetate, formate, and lactate content in culture supernatants was determined by ICS 2100 ion chromatography (Dionex Instruments, Sunnyvale, CA) with a Dionex IonPac AS-19 column and a 1–40 mmol/L KOH gradient mobile phase.

Results

Exploration of microorganisms strengthening tight junction barrier

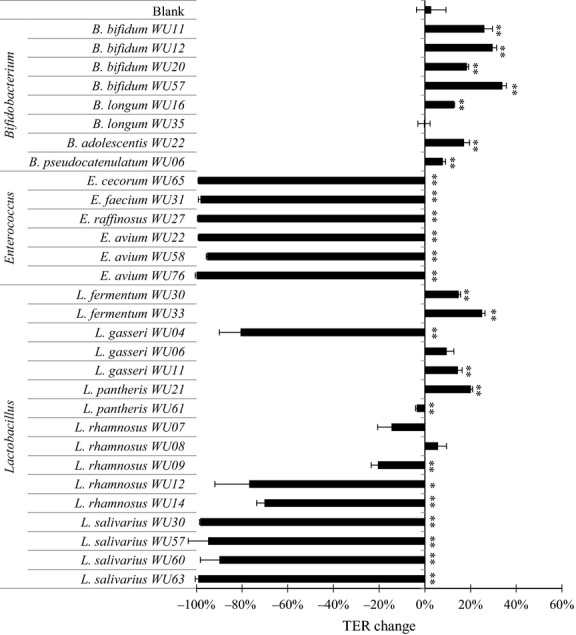

After the polarized Caco-2 cell monolayers were incubated with each bacterial isolate or medium alone for 24 h, the intestinal barrier function was determined by measurement of the TER (Fig.1 and Table2). All Enterococcus isolates (including E. faecium, E. avium, E. cecorum, and E. raffinosus) induced an appreciable decrease in TER. Some Lactobacillus species (L. gasseri, L. rhamnosus, and L. salivarius) also induced a significant decrease in TER. In contrast, seven Bifidobacterium isolates and six Lactobacillus isolates induced a 5.7–33.9% increase in TER. Therefore, we examined the preventive effects of these screened isolates (7 strains of Bifidobacterium and 6 strains of Lactobacillus) on TNF-α-induced impairment of TJ permeability.

Figure 1.

Screening of bacterial isolates for TJ-barrier-strengthening effects in polarized Caco-2 monolayers at MOI = 1. All the bacteria isolates were incubated with Caco-2 monolayers for 24 h. The average of actual TER values of Caco-2 monolayer used in this experiment was 1057 ± 98 Ω cm2. Experiments were carried out in triplicate, and data represent the means of relative changes in TER ± SD. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 compared with the blank (media alone) control group by t-test.

Table 2.

The TER value measured at the screening of bacterial isolates for TJ-barrier-strengthening effects in polarized Caco-2 monolayers

| Genus | Species | Strain | 0 h | 24 h coincubation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TER (Ω × cm2) | ±SD | TER (Ω × cm2) | ±SD | |||

| – | – | Blank | 1085.1 | 53.7 | 1115.3 | 90.5 |

| Lactobacillus | fermentum | WU30 | 1194.5 | 16.7 | 1371.8 | 13.8 |

| WU33 | 927.9 | 32.6 | 1160.9 | 38.1 | ||

| gasseri | WU04 | 919.3 | 37.5 | 176.4 | 81.5 | |

| WU06 | 1056.3 | 24.8 | 1157.1 | 38.7 | ||

| WU11 | 1074.6 | 57.8 | 1229.9 | 49.8 | ||

| pantheris | WU21 | 1069.0 | 23.4 | 1283.7 | 35.6 | |

| WU61 | 1098.9 | 31.4 | 1059.3 | 24.9 | ||

| rhamnosus | WU07 | 1109.4 | 22.7 | 948.5 | 87.2 | |

| WU08 | 1095.9 | 33.4 | 1158.6 | 44.4 | ||

| WU09 | 1138.9 | 31.1 | 904.4 | 22.7 | ||

| WU12 | 1171.7 | 18.9 | 272.3 | 177.9 | ||

| WU14 | 1150.8 | 24.4 | 342.5 | 35.3 | ||

| salivarius | WU30 | 1160.1 | 67.2 | 19.2 | 2.3 | |

| WU57 | 1081.7 | 3.4 | 55.8 | 94.7 | ||

| WU60 | 1089.6 | 43.5 | 109.2 | 89.4 | ||

| WU63 | 1159.8 | 71.9 | 9.5 | 15.5 | ||

| Enterococcus | avium | WU22 | 1050.4 | 51.5 | 9.9 | 2.6 |

| WU58 | 1092.9 | 30.6 | 51.0 | 3.0 | ||

| WU76 | 935.8 | 45.1 | 0.9 | 5.6 | ||

| cecorum | WU65 | 1100.4 | 31.4 | 9.9 | 2.3 | |

| faecium | WU31 | 1162.0 | 27.2 | 20.7 | 10.8 | |

| raffinosus | WU27 | 1135.5 | 71.2 | 6.5 | 1.7 | |

| Bifidobacterium | adolescentis | WU22 | 959.7 | 15.2 | 1123.9 | 25.6 |

| bifidum | WU11 | 911.9 | 60.8 | 1148.6 | 54.7 | |

| WU12 | 900.3 | 74.1 | 1166.5 | 82.0 | ||

| WU20 | 1085.1 | 32.1 | 1284.5 | 30.4 | ||

| WU57 | 873.8 | 15.5 | 1170.2 | 29.8 | ||

| longum | WU16 | 1029.1 | 19.5 | 1160.5 | 23.6 | |

| WU35 | 1033.9 | 21.5 | 1030.2 | 38.7 | ||

| pseudocatenulatum | WU06 | 923.8 | 100.5 | 997.4 | 114.5 | |

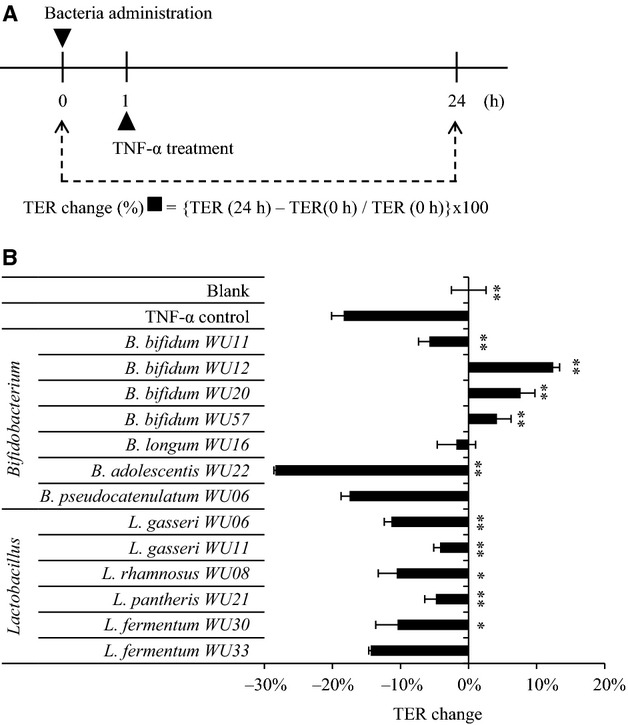

Evaluation of preventive effect of screened bacteria on TNF-α-induced impairment of tight junction function

TNF-α treatment induced a marked decrease in TER of the Caco-2 cell monolayers. Pretreatment with Lactobacillus strains did not attenuate the TNF-α-induced decrease in TER (Fig.2 and Table3). In contrast, four of the seven Bifidobacteria strains prevented the TNF-α-induced drop in TER. Interestingly, exposure to three Bifidobacteria strains (B. bifidum WU12, WU20, and WU57) led to a reproducible and significant 4.2–12.4% increase in TER (P < 0.01). Additionally, one Bifidobacteria strain (B. bifidum WU11) and two Lactobacillus strains (L. gasseri WU11 and L. pantheris WU21) demonstrated partial suppression of the TNF-α-induced TER drop, (−4.2 to −5.8% change).

Figure 2.

The preventive effect against TNF-α-induced TJ barrier impairment. (A) Schedule of Caco-2 monolayer treatment and TER analysis. The bacterial suspensions were added to the apical side of Caco-2 monolayers an hour before TNF-α stimulation. After 1 h, Caco-2 monolayers were stimulated on the basolateral side with TNF-α, and then incubated for 24 h. (B) The preventive effect of bacterial isolates with barrier-strengthening ability at MOI = 1. The average of actual TER values of Caco-2 monolayer used in this experiment was 976 ± 166 Ω cm2. Experiments were carried out in triplicate, and data represent the means of relative changes of TER ± SD. **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 compared with the TNF-α control group by t-test.

Table 3.

The TER value measured at the screening of preventive effect against TNF-α-induced TJ barrier impairment

| Genus | Species | Strain | 0 h | 24 h coincubation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TER (Ω × cm2) | ±SD | TER (Ω × cm2) | ±SD | |||

| – | – | Blank | 979.1 | 79.5 | 978.3 | 63.1 |

| – | – | TNF-α control | 948.5 | 117.2 | 774.1 | 92.9 |

| Lactobacillus | fermentum | WU30 | 1262.1 | 32.4 | 1129.5 | 11.4 |

| WU33 | 996.6 | 35.1 | 853.3 | 27.3 | ||

| gasseri | WU06 | 1215.8 | 67.3 | 1078.4 | 67.6 | |

| WU11 | 846.2 | 35.9 | 810.7 | 32.6 | ||

| pantheris | WU21 | 880.5 | 19.8 | 837.9 | 9.8 | |

| rhamnosus | WU08 | 1235.2 | 36.4 | 1104.1 | 10.6 | |

| Bifidobacterium | adolescentis | WU22 | 1031.7 | 49.1 | 739.0 | 34.1 |

| bifidum | WU11 | 858.1 | 67.3 | 808.1 | 51.0 | |

| WU12 | 751.0 | 34.7 | 844.3 | 35.1 | ||

| WU20 | 775.2 | 16.1 | 834.2 | 1.3 | ||

| WU57 | 794.6 | 1.6 | 827.7 | 18.2 | ||

| longum | WU16 | 1043.7 | 47.7 | 1024.2 | 28.4 | |

| pseudocatenulatum | WU06 | 958.2 | 21.4 | 790.5 | 10.8 | |

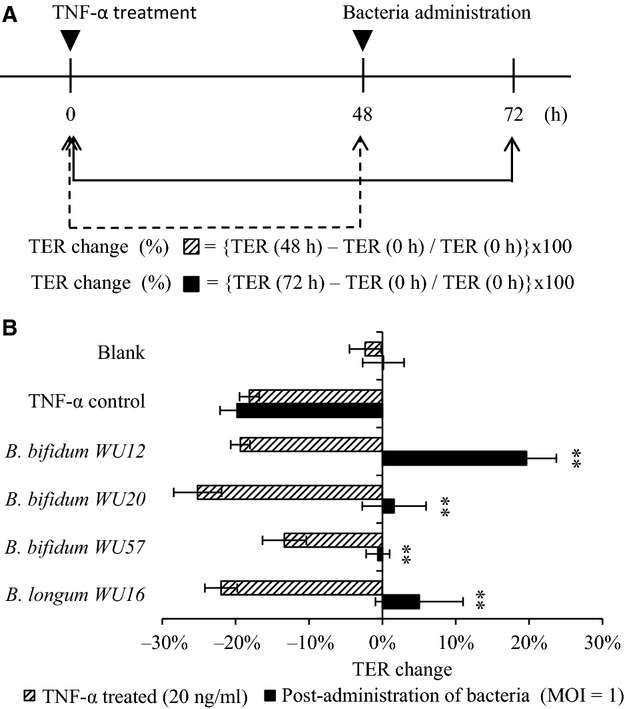

Evaluation of bacteria-induced restoration of epithelial function

In this study, the addition of TNF-α (20 ng/mL) to the basolateral compartment produced an approximately 15–20% drop in Caco-2 TER for 48 h. TER of TNF-α-treated Caco-2 cell monolayers did not increase after changing to fresh medium without TNF-α, indicating no spontaneous recovery of the Caco-2 monolayer TJ function. Based on the above results, it was hypothesized that the four Bifidobacteria strains (B. bifidum strain WU12, WU20, WU57, and B. longum strain WU16) which exhibited protective effects against TNF-α induced damage could also be involved in the restoration of intestinal epithelial TJ function. Thus, we examined whether Bifidobacteria strains can restore the TJ function of Caco-2 cell monolayers damaged by the treatment of TNF-α. As a result, all tested Bifidobacterium (3 strains of B. bifidum, 1 strain of B. longum) facilitated the restoration of the Caco-2 TJ function (Fig.3 and Table4). To elucidate the mechanism of Bifidobacteria-induced epithelial restoration, B. bifidum strain WU12 was chosen for further study.

Figure 3.

Repair of TNF-α-induced barrier dysfunction by administration of bacterial isolates post TNF-α stimulation. (A) The schedule of TNF-α and bacterial treatment of Caco-2 monolayers. Caco-2 monolayers were stimulated on the basolateral side with TNF-α, and then incubated for 48 h. After 48 h, the bacterial suspension were added into the apical side, and coincubated for 24 h. (B) Repair effect of four Bifidobacterial species on the TJ function of Caco-2 cell monolayer damaged by basolateral TNF-α stimulation. The average of actual TER values of Caco-2 monolayer used in this experiment was 879 ± 147 Ω cm2. Experiments were carried out in triplicate, and data represent the means of relative changes in TER ± SD. **P < 0.01 compared with the TNF-α treated TER of the same group by t-test.

Table 4.

The TER value measured at the repairing of TNF-α-induced barrier dysfunction by administration of bacterial isolates post TNF-α stimulation

| Genus | Species | Strain | Before treatment | TNF-α treated | 24 h coincubation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TER (Ω × cm2) | ±SD | TER (Ω × cm2) | ±SD | TER (Ω × cm2) | ±SD | |||

| – | – | Blank | 696.8 | 14.9 | 680.8 | 27.4 | 697.9 | 30.2 |

| – | – | TNF-α control | 1050.6 | 14.7 | 860.2 | 20.7 | 842.2 | 12.7 |

| Bifidobacterium | longum | WU16 | 1026.9 | 71.2 | 800.2 | 37.8 | 1077.6 | 83.0 |

| bifidum | WU12 | 884.6 | 66.6 | 712.9 | 41.8 | 1058.2 | 84.1 | |

| WU20 | 903.3 | 40.0 | 675.5 | 32.6 | 918.6 | 73.4 | ||

| WU57 | 709.1 | 36.5 | 613.9 | 20.2 | 705.0 | 44.0 | ||

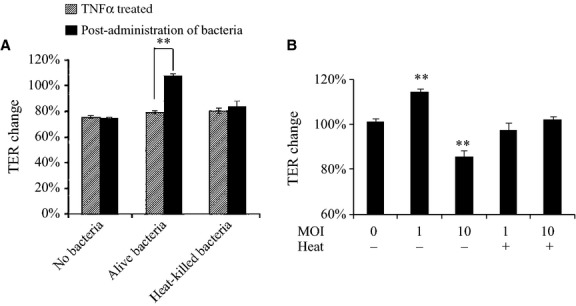

Characterization of the factor responsible for B. bifidum-induced restoration of epithelial function

We determined whether the bacterial components or secreted metabolites were responsible for the epithelial TJ restoration induced by B. bifidum strain WU12. Heat-killed B. Bifidum WU12 clearly had a diminished a repair capacity (Fig.4A and Table5A). Interestingly, only intact cells of B. bifidum strain WU12 resulted in a pronounced increase in TER of the Caco-2 cell monolayers, indicating a high repair capacity on the epithelial TJ. Thus, the interaction between live Bifidobacterium and Caco-2 cells are a prerequisite for Bifidobacteria-induced epithelial restoration. However, high-dose administration of intact bacterial cells at a MOI of 10 resulted in a significant decrease in TER of TNF-α-untreated Caco-2 cell monolayers (Fig.4B and Table5B). This might be due to the acceleration of medium acidification, as suggested by the medium turning yellow during the coculture of Caco-2 cells and live Bifidobacterium.

Figure 4.

Characterization of the factor responsible for B. bifidum-induced TJ restoration. (A) Effects of the heat treatment (95°C for 10 min) of bacterial cells on B. bifidum WU12-induced epithelial TJ restoration capacity. The average of actual TER values of Caco-2 monolayer before basolateral TNF-α stimulation used in this experiment was 894 ± 99 Ω cm2. Experiments were carried out in triplicate, and data represent the means of relative changes in TER ± SD before and after administration of B. bifidum WU12. Statistical differences between before and after administration of B. bifidum WU12 in each experimental group were calculated by t-test (**P < 0.01). (B) The cytotoxic effect of MOI on cocultivation of Caco-2 monolayers with alive or heat-killed B. bifidum WU12. The average of actual TER values of Caco-2 monolayer used in this experiment was 753 ± 91 Ω cm2. Experiments were carried out in triplicate, and data represent the means of relative changes of TER ± SD. Statistical differences before and after administration of alive or heat-killed B. bifidum WU12 were calculated by t-test (**P < 0.01).

Table 5.

The TER value measured at the (A) The effects of MOI on cocultivation of Caco-2 monolayers with live/heat inactive B. bifidum WU12, (B) characterization of B. bifidum WU12-induced epithelial TJ restoration with live/heat-killed bacteria

| (A) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | TNF-α treated | Postadministration of bacteria | ||

| TER (Ω × cm2) | ±SD | TER (Ω × cm2) | ±SD | |

| No bacteria | 734.5 | 13.4 | 727.1 | 18.8 |

| Alive bacteria (MOI=1) | 652.0 | 11.7 | 888.0 | 12.1 |

| Heat-killed bacteria (MOI=1) | 709.1 | 102.1 | 739.4 | 90.0 |

| (B) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | 0 h | 24 h coincubation | ||

| TER (Ω × cm2) | ±SD | TER (Ω × cm2) | ±SD | |

| No bacteria | 867.4 | 71.2 | 879.0 | 78.1 |

| Alive bacteria (MOI=1) | 692.7 | 75.9 | 791.3 | 89.5 |

| Alive bacteria (MOI=10) | 655.0 | 42.3 | 558.7 | 19.7 |

| Heat-killed bacteria (MOI=1) | 739.8 | 24.2 | 721.5 | 17.0 |

| Heat-killed bacteria (MOI=10) | 807.7 | 4.7 | 824.1 | 8.5 |

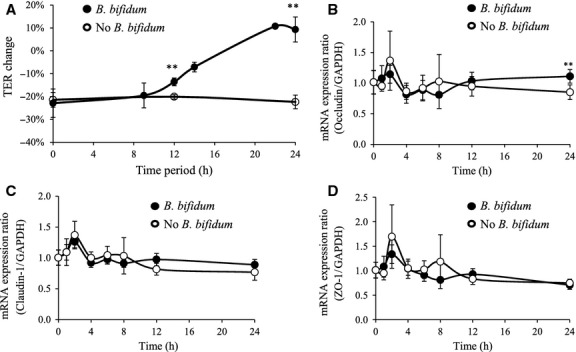

Modulation of the mRNA expression of tight junction proteins by B. bifidum

The kinetics of TER change during B. bifidum-induced epithelial restoration is shown in Figure5A and Table6. A rapid increase in TER was observed after 12 h of coincubation which reached 9.3% at 24 h. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis was performed to characterize the changes in gene expression of tight junction proteins during B. bifidum-induced epithelial restoration. Although the expression dynamics of the TJ protein genes during the coincubation period were not correlated with the change in TER in Caco-2 cells incubated with B. bifidum, the administration of B. bifidum significantly enhanced the occludin mRNA expression after 24 h incubation (Fig.5B, C, and D).

Figure 5.

The kinetics of TER and TJ-related mRNA expression during B. bifidum WU12-induced Caco-2 monolayer restitution. (A) B. bifidum WU12-induced Caco-2 monolayer restitution over time as estimated by TER. Caco-2 monolayers incubated without B. bifidum WU12 were used as the negative control. The average of actual TER values of Caco-2 monolayer before basolateral TNF-α stimulation used in this experiment was 822 ± 86 Ω cm2. Experiments were carried out in triplicate, and data represent the means of relative changes of TER ± SD. (B–D) Temporal changes of mRNA expression changes in TJ protein genes (Claudin-1, Occludin, ZO-1) during Caco-2 monolayer restitution induced by B. bifidum WU12. The time course of mRNA expression of nontreated group (w/o B. bifidum) was used as the negative control. Experiments were carried out in triplicate, and data represent the means of relative changes in ± SD. Statistical differences were calculated by t-test, comparing conditions with the negative control group at the same time point (**P < 0.01).

Table 6.

The TER value measured during the B. bifidum WU12-induced Caco-2 monolayer restitution in 24 h

| Sample | B. bifidum | NO B. bifidum | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TER (Ω × cm2) | ±SD | TER (Ω × cm2) | ±SD | |

| Naïve cell | 890.0 | 124.7 | 762.1 | 35.8 |

| 0 h (TNF-α treated) | 682.9 | 89.1 | 598.1 | 20.0 |

| 9 h | 727.6 | 71.1 | ||

| 12 h | 782.5 | 111.3 | 598.5 | 18.8 |

| 14 h | 706.3 | 17.4 | ||

| 22 h | 910.9 | 20.1 | ||

| 24 h | 869.9 | 14.2 | 596.6 | 24.8 |

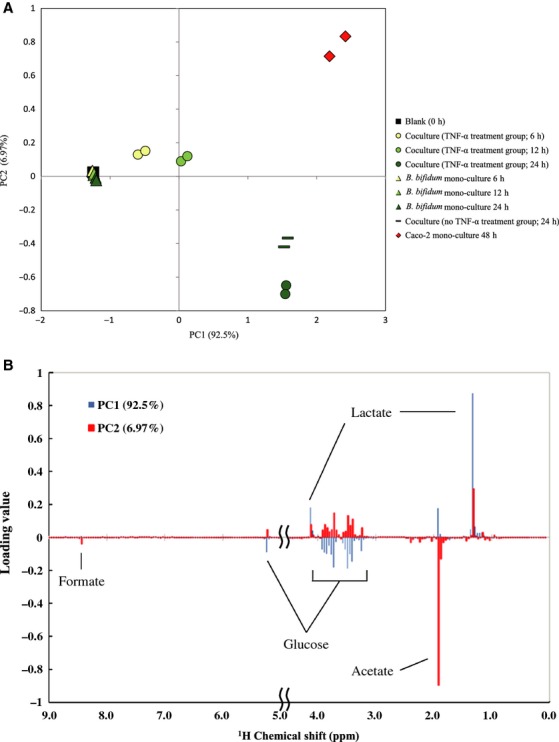

Time-course characterization of the coculture supernatant

Based on the above results, it was hypothesized that metabolites produced by B. bifidum strain WU12 play a crucial role in the process of Bifidobacteria-induced epithelial restoration. To characterize the metabolic dynamics during the epithelial restoration, time-course metabolic profiles of the apical side supernatant were determined using a 1H-NMR-based metabonomics approach. The principal component analysis (PCA) of the 1H NMR chemical shift data revealed clear differences in metabolite profiles between the coculture groups, the monoculture of B. bifidum, and the monoculture of Caco-2 cell monolayers (Fig.6). Contributions of the first two components (PC1 and PC2) were 92.5% and 6.97%, respectively (Fig.6A). The loading plot analysis showed that the major metabolites contributing to the separation of each component were lactate and glucose in PC1 and acetate and formate in PC2 (Fig.6B). In the metabolite profile of B. bifidum alone group, there was only a minute amount of acetate production detected during cultivation. In the Caco-2 monoculture treated with TNF-α for 48 h, glucose was consumed and a large amount of lactate produced. In contrast, the coculture of B. bifidum and Caco-2 notably enhanced the production of acetate after 12 h of the incubation. Furthermore, formate was also produced in the coculture of B. bifidum and Caco-2.

Figure 6.

Principle component analysis (PCA) score plots and loading plots of the metabolic profile affected by B. bifidum WU12. (A) PCA score plot was computed from blank (square), Caco-2 mono-culture 48 h (with TNF-α; diamond), time-dependent change of the coculture group (TNF-α treated; circle), time-dependent change in B. bifidum WU 12 mono-culture group (triangle), B. bifidum WU12 coculture control (dash). (B) PCA loading plot derived from the information on the PCA score plots. Experiments were carried out in duplicate.

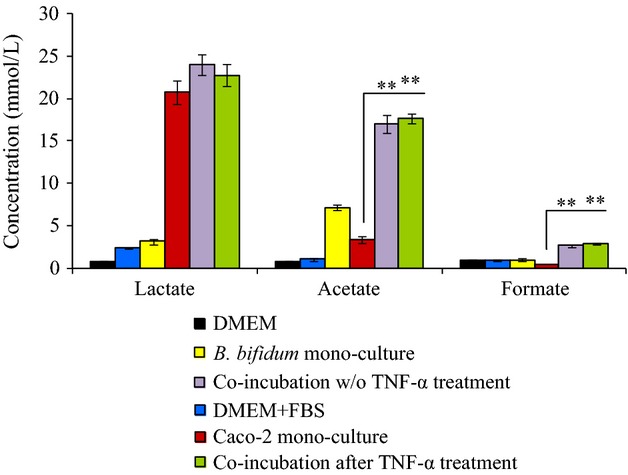

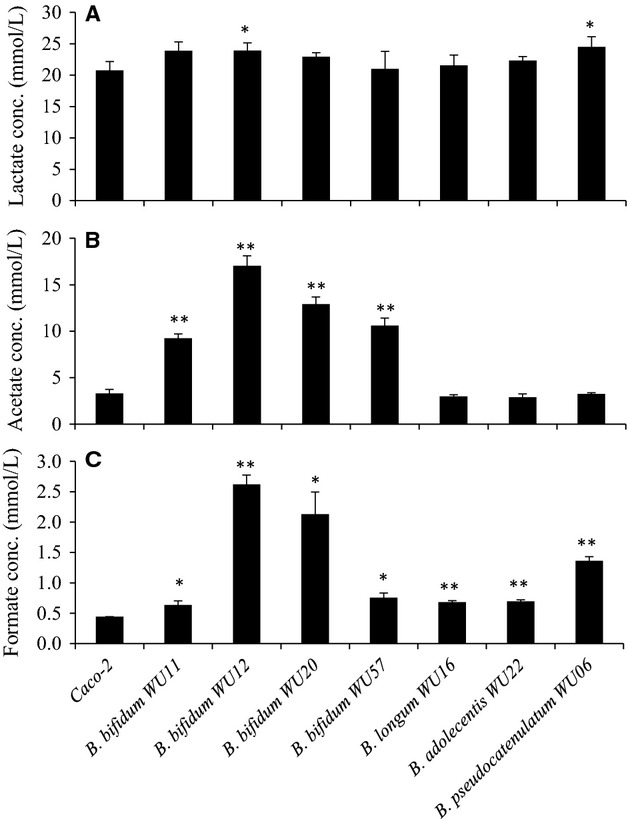

Evaluation of the production of acetate, formate, and lactate in the coculture supernatant of Bifidobacterium isolates and Caco-2 cells

We conducted ion chromatography analysis to determine the production of acetate, formate and lactate in the supernatant during coculture of Caco-2 and B. bifidum WU12, with and without TNF-α, and by B. bifidum alone (Fig.7). Interestingly, the production of acetate and formate was amplified by the coculture of B. bifidum WU12 and Caco-2 monolayers. Acetate production in the coculture group increased 1.8 times compared with that of the monoculture of the B. bifidum strain WU12. Furthermore, we determined whether the production of acetate, formate, and lactate in the coculture supernatant differed between the seven Bifidobacterium strains, which fortified the epithelial TJ barrier of naive polarized Caco-2 cells (Fig.1). Analysis of the culture supernatant revealed that the production of lactate was mainly derived from cell metabolism of Caco-2 cells as there were no differences between the monoculture of Caco-2 and the coculture of Caco-2 and Bifidobacterium (Fig.8). In contrast, the production of acetate and formate varied among Bifidobacterium species. Notably, B. bifidum produced higher levels of acetate and formate in comparison with other species (B. adolescentis, B. longum, and B. pseudocatenulatum) (Fig.8).

Figure 7.

Increased production of acetate and formate by the cocultures of Caco-2 monolayer and B. bifidum WU. Acetate, formate, and lactate concentrations in the culture supernatant after 24 h incubation were determined by ion chromatography. Experiments were carried out in triplicate, and data represent the means ± SD. Statistical differences were calculated by t-test (**P < 0.01).

Figure 8.

Production of acetate and formate in the coculture supernatant varied in a strain-dependent manner. (A–C) Acetate, formate, and lactate concentrations in the supernatant after 24 h cocultures of Caco-2 monolayer and seven different Bifidobacterial strains were determined by ion chromatography. Experiments were carried out in triplicate, and data represent the means ± SD. Statistical differences were calculated by t-test (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05).

Effects of acetate and formate on TJ barrier function in Caco-2 monolayers

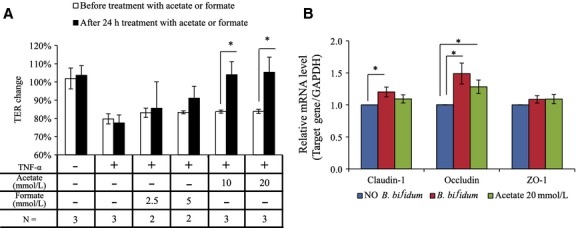

We determined whether acetate and formate might be involved in TJ barrier restoration of Caco-2 monolayers whose TER were decreased approximately 20% by basolateral TNF-α stimulation for 48–72 h. Interestingly, administration of 10 and 20 mmol/L acetate to the apical side to the TNF-α treated Caco-2 monolayers showed a marked restorative effect after 24 h incubation (P < 0.05) (Fig.9A and Table7). On the other hand, the restorative effect of formate was weaker than the effect of acetate. Furthermore, occludin mRNA expression were significantly enhanced by apical stimulation with acetate (20 mmol/L) as the case of administration of B. bifidum WU12 (Fig.9B). Occludin mRNA levels by acetate or B. bifidum WU12 were 1.28-fold and 1.49-fold, respectively (P < 0.05). On the other hand, apical stimulation with acetate had no significant effect on the gene expression of claudin-1 and ZO-1.

Figure 9.

Acetate induced the TJ barrier restorative capacity. (A) Effects of acetate and formate on the TJ barrier restoration. Caco-2 monolayers were stimulated on the basolateral side with TNF-α, and then incubated for 48 h. After 48 h, acetate or formate were added into the apical side, and incubated for 24 h. The average of actual TER values of Caco-2 monolayer used in this experiment was 846 ± 96 Ω cm2. Data represent the average of two or three independent experiments carried out in triplicate. (B) Effects of acetate or B. bifidum WU12 on mRNA expression of TJ protein genes. TJ protein gene expressions in Caco-2 cells treated with acetate or B. bifidum WU12 for 24 h was were determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Data represent the average of three independent experiments carried out in duplicate or triplicate. Statistical differences were calculated by t-test (*P < 0.05).

Table 7.

The TER value measured at the experiment of 24 h apical treatment of Caco-2 monolayers with varying concentrations of acetate and formate to induce the TJ barrier restorative effects

| Sample | Before experiment | TNF-α treated | 24 h treatment | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TER (Ω × cm2) | ±SD | TER (Ω × cm2) | ±SD | TER (Ω × cm2) | ±SD | |

| Blank | 768.1 | 120.0 | 787.2 | 165.6 | 800.1 | 162.0 |

| TNF-α | 875.0 | 89.5 | 698.2 | 91.6 | 678.8 | 92.9 |

| Formate 2.5 mmol/L | 809.9 | 95.3 | 669.3 | 92.0 | 669.3 | 156.1 |

| Formate 5 mmol/L | 828.0 | 89.1 | 688.4 | 78.6 | 743.2 | 114.9 |

| Acetate 10 mmol/L | 822.0 | 126.3 | 688.4 | 109.1 | 858.2 | 181.6 |

| Acetate 20 mmol/L | 823.8 | 105.0 | 691.0 | 97.7 | 868.7 | 144.6 |

Dependency of Bifidobacteria-induced TER restoration on the differentiation stage of Caco-2 cells

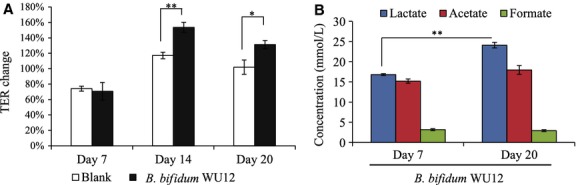

To investigate whether the TER-enhancing effect of B. bifidum depends on polarization of the intestinal epithelial cells, we determined the TER-enhancing activity in untreated Caco-2 cells at three different time points (Fig.10A and Table8): day 7, unpolarized; day 14, early-polarization; day 20, stable-polarization. In the early- and stable-polarization stages, the TER values of the Caco-2 cell monolayers significantly increased by approximately 30% in coculture with B. bifidum WU12. In contrast, B. bifidum-induced TER-enhancing effect in unpolarized Caco-2 cells was weak compared with that in polarized Caco-2 cells. Interestingly, the differential stage of Caco-2 cells did not affect the production of acetate and formate in the coculture of B. bifidum WU 12 and Caco-2 monolayers (Fig.10B). These results suggest that the acetate-induced TER-enhancing effect depends on the differentiation stage of the intestinal epithelial cells.

Figure 10.

Characterization of B. bifidum-induced strengthening epithelial barrier function at different time points during Caco-2 monolayer polarization. (A) B. bifidum-induced TER enhancement: Day7, nonpolarization (actual TER values, 307 ± 77 Ω cm2); Day14, early-polarization (actual TER values, 508 ± 19 Ω cm2); Day20, stable-polarization (actual TER values, 806 ± 49 Ω cm2). TER changes were calculated from the TER value measured before and 24 h after the coincubation with B. bifidum WU12. Data represent the average of three independent experiments carried out in triplicate. (B) Short chain fatty acids production in nonpolarized (Day 7) or stable-polarized Caco-2 cells (Day 20) treated with B. bifidum WU12. Experiments were carried out in triplicate, and data represent the means ± SD. Statistical differences were calculated by t-test (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05).

Table 8.

The TER value measured at the characterization of B. bifidum-induced strengthening epithelial barrier function at different timepoints during Caco-2 monolayer polarization

| Period | Sample | 0 h | 24 h coincubation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TER (Ω × cm2) | ±SD | TER (Ω × cm2) | ±SD | ||

| Day7 | Blank | 306.6 | 86.0 | 229.0 | 72.0 |

| B. bifidum WU12 | 307.5 | 94.3 | 224.1 | 94.8 | |

| Day 14 | Blank | 499.7 | 7.1 | 585.4 | 23.3 |

| B. bifidum WU12 | 516.9 | 6.2 | 794.5 | 38.8 | |

| Day 20 | Blank | 816.5 | 50.9 | 830.0 | 41.7 |

| B. bifidum WU12 | 796.1 | 35.6 | 1043.5 | 28.6 | |

Discussion

Dysregulation of intestinal permeability allows paracellular permeation of luminal antigens that initiate or promote intestinal inflammation. Thus, a defective intestinal TJ barrier has been proposed as an etiological factor for various gastrointestinal and systemic diseases with chronic inflammation, including allergy, celiac disease, Crohn's disease, diabetes, multiple sclerosis, and irritable bowel syndrome (Arrieta et al. 2006; Groschwitz and Hogan 2009). Recent studies demonstrated that various dietary components or probiotics regulate epithelial permeability by modifying intracellular signal transduction involved in the expression and localization of TJ proteins (Ulluwishewa et al. 2011). Administration of probiotics capable of colonizing the intestine is expected to induce long-term beneficial effects on intestinal health, whereas orally delivered dietary components have only a transient effect. In this study, we investigated the regulation of epithelial TJ barrier function by human fecal bacterial strains from the three bacterial genera (i.e., Bifidobacterium, Enterococcus, and Lactobacillus) most commonly used as probiotics for human consumption. This study demonstrated that some Bifidobacterium strains protect the epithelial TJ barrier against TNF-α-induced injury and promote the restoration of TNF-α-induced loss of epithelial barrier integrity. Furthermore, we showed that B. bifidum-induced restoration of epithelial TJ barrier may be attributed to increased production of acetate and formate, as demonstrated in cocultures of B. bifidum and Caco-2 cells.

Our present data showed that the permeability of Caco-2 epithelial cell monolayers exposed to live bacterial cells was altered depending on the bacterial strain. Many strains of Bifidobacterium species and some strains of Lactobacillus species significantly increased the TER of the Caco-2 cell monolayers, whereas all strains of Enterococcus species tested in this study dramatically decreased the TER. Therefore, in this study, we did not evaluate whether Enterococcus species have the capacity for the protection or restoration of the epithelial TJ barrier. However, these results do not mean that all of Enterococcus species are incapable of strengthening epithelial TJ function. Compared with probiotic strains belonging to the genera Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, Enterococcus species are used as probiotics to a much lesser extent because some strains possess virulence factors (including adhesins, invasins, pili, and hemolysin) and are resistant to various antibiotics (Franz et al. 2011). Steck et al. showed that a strain of the gut commensal E. faecalis compromises the epithelial barrier by metalloprotease-triggered degradation of the extracellular domain of E-cadherin (Steck et al. 2011). In contrast, some probiotic strains of E. faecium and E. faecalis are produced in the form of pharmaceutical preparations for treatment of diarrhea, immune modulation and lowering of serum cholesterol. Furthermore, Miyauchi et al. showed that pretreatment of heat-killed Enterococcus hirae prevented TNF-α-induced barrier impairment by modulating intracellular signaling pathways, suggesting that its cell wall components lead to the enhancement of the epithelial TJ barrier (Miyauchi et al. 2008). However, in this study, the heat-killed B. bifidum WU12 lost the TJ repair capacity completely. This suggests that the main inducing factor of this beneficial effect might be the metabolites of bacteria, not the cell wall components.

We found that different species of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus differentially attenuated TNF-α-induced reduction in TER of Caco-2 cell monolayers. Similarly, previous studies have shown that pretreatment with some commensal and probiotic bacteria can inhibit the increase in the epithelial TJ permeability caused by infection, proinflammatory cytokines, and stress (Resta-Lenert and Barrett 2003; Donato et al. 2010; Miyauchi et al. 2012). Molecular mechanisms underlying the protective effect are only partially understood. It is well established that treatment of intestinal epithelial cells with TNF-α promotes the redistribution of several TJ proteins (including claudin-1, occludin, and ZO-1) and impairs epithelial barrier function (Groschwitz and Hogan 2009). In particular, myosin light chain kinase (MLCK)-mediated phosphorylation of the myosin light chain (MLC), which induces the contraction of perijunctional actin–myosin filaments and opening of the epithelial TJ structure, appears to be a central molecular mechanism of TNF-α-induced loss of epithelial barrier function (Turner et al. 1997; Zolotarevsky et al. 2002; Ma et al. 2005; Shen et al. 2006). Previous studies showed that certain probiotic and commensal bacteria (i.e., Enterococcus hirae and Lactobacillus rhamnosus) suppressed the TNF-α-induced decrease in TER of Caco-2 cell monolayers by decreasing MLCK expression (Miyauchi et al. 2008, 2009). Furthermore, Ye et al. revealed that the TNF-α-induced increase in MLCK expression was mediated through activation of the nuclear transcription factor NF-κB, which is considered as the master regulator of inflammatory responses (Ye et al. 2006). Thus, the suppression of TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation, rather than modulation of TJ proteins, is thought to be a pivotal process for prevention of TNF-α-induced barrier impairment by commensal and probiotic bacteria. In other words, beneficial bacteria that confer preventive effects against TNF-α-induced TJ disruption could also exert antiinflammatory effects on intestinal epithelial cells by inhibiting NF-κB activation.

There are only a limited number of studies focusing on the therapeutic effects of probiotics on impaired epithelial barrier function, as compared with multiple reports regarding preventive or protective effects of probiotics on TJ integrity against harmful stimuli (e.g., cytokines, infection, and H2O2). In a previous report, the probiotic E. coli Nissle 1917 led to restoration of a disrupted epithelial barrier of T84 cell monolayer caused by pathogenic E. coli infection, which was associated with increased expression and relocalization of zonula occludens-2 (ZO-2) (Zyrek et al. 2007). Our study demonstrated that Bifidobacterium species promoted the restoration of the epithelial TJ barrier of Caco-2 cell monolayer, in which TJ barrier integrity was impaired by pretreatment of TNF-α. Notably; B. bifidum WU12 exerted the highest TER-restorative effect on Caco-2 cell monolayers among the tested Bifidobacterium strains. Interestingly, B. bifidum-induced increase in TER was accompanied by an increase in mRNA expression of occludin. Balda et al. showed that the overexpression of occludin was linked to an increase in TER (Balda et al. 1996). From these findings, increased occludin gene expression may contribute to the ability of B. bifidum to restore the epithelial TJ barrier. In contrast, B. bifidum did not alter the mRNA expression of other TJ-related proteins (i.e., claudin-1 and ZO-1). In previous studies, the treatment of epithelial monolayers with probiotics (specifically L. rhamnosus GG, L. plantarum, and L. salivarius) enhanced protein expression of the occludin-associated plaque proteins (ZO-1, ZO-2, and cingulin) and other TJ-related proteins (claudin-1, claudin-3, and JAM-1) by IECs (Anderson et al. 2010; Miyauchi et al. 2012; Patel et al. 2012). Thus, epithelial barrier integrity may be further enhanced by administration of a mixture of multiple probiotic species each capable of modulating specific TJ proteins. Furthermore, the paracellular permeability of IECs are affected by expression levels and localization of TJ proteins in the paracellular space. Further study assaying the expression level and localization of TJ proteins during the B. bifidum-induced TJ restoration will be carried out to elucidate the cellular mechanisms.

Live B. bifidum had a restorative effect on the TER in TJ-impaired Caco-2 cell monolayers, whereas this effect was diminished when treated with heat-killed bacteria. It was previously reported that metabolites from B. infantis or B. lactis prevented epithelial barrier dysfunction caused by proinflammatory cytokines or pathogen infection (Ewaschuk et al. 2008; Putaala et al. 2008). Thus, we speculate that some of B. bifidum-derived metabolites may also regulate the epithelial TJ. In this study, NMR-based metabonomics analysis of the coculture supernatant revealed that SCFAs (acetate and formate) are responsible for the TER-restorative effect induced by live B. bifidum. Interestingly, production of acetate and formate was upregulated in the coculture environment compared with the monoculture of Bifidobacterium strain or Caco-2 monolayers, indicating that cross talk between the host and microbes may alter their metabolic activity. Further studies are needed to clarify which cells enhanced the production of acetate or formate by coculture. Furthermore, we observed that production levels of acetate and formate in the coculture varied depending on the Bifidobacterium strain. There are previous reports showing the beneficial effect of SCFAs on TER and paracellular permeation in Caco-2 cell monolayers (Mariadason et al. 1997; Malago et al. 2003; Suzuki et al. 2008; Elamin et al. 2013). Notably, Suzuki et al. presented the finding that the incubation of Caco-2 cell monolayers with acetate (>40 mmol/L) led to a significant increase in the epithelial TJ barrier function. They suggested that acetate-induced TJ enforcement may be mediated by intracellular signal transduction through GPR43, which has been defined as one of the cell surface G-protein coupled receptors for SCFAs (Brown et al. 2003; Suzuki et al. 2008). However, the molecular mechanism underlying acetate-mediated fortification of intestinal epithelial barrier remains unclear. In contrast, our data suggest that B. bifidum-induced epithelial TJ enforcement was dependent on the differentiation stage of Caco-2 cell monolayers. In future experiments we will elucidate the molecular mechanism involved, including the investigation of the GPR43-acetate signaling pathway.

Probiotic microorganisms (e.g., Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus) exert their immune-modulatory effect through interaction with Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), which recognizes cell wall components such as peptidoglycan, lipoteichoic acid, and lipoprotein (Mohamadzadeh et al. 2005; Galdeano and Perdigon 2006; Hoarau et al. 2006; Zeuthen et al. 2008). Furthermore, recent studies have shown that TLR2 stimulation plays a crucial role in maintaining intestinal epithelial barrier integrity. Stimulation with the synthetic TLR2 agonist PCSK efficiently preserves TJ-associated barrier integrity (Cario et al. 2004, 2007). Cell wall components derived from some Bifidobacterium and Enterococcus strains are also reported to markedly enhance epithelial TJ barrier through a TLR2-mediated mechanism (Miyauchi et al. 2008; Sultana et al. 2013). This study showed that heat-killed B. bifidum slightly increased TER of Caco-2 cell monolayers, whereas lipase and mutanolysin treatment to digest lipid-related components abolished the rise in TER elicited by B. bifidum. These results suggest that cross talk between B. bifidum and TLR2 plays a partial role in the modulation of intestinal epithelial TJ barrier function.

In summary, we demonstrated that most of Bifidobacterium strains have the capacity to prevent TNF-α-induced disruption of intestinal epithelial barrier and to promote epithelial TJ integrity. Furthermore, it was found that the upregulation of the production of SCFAs (acetate and formate) leads to the restoration of the epithelial TJ barrier. Our findings show that TJ-strengthening Bifidobacterium strains could make an important contribution to the prevention and treatment of various digestive system disorders associated with intestinal epithelial barrier dysfunction (including diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease). However, studies using animal models are still required to evaluate in vivo the beneficial effects seen here in vitro.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Anderson RC, Cookson AL, McNabb WC, Park Z, McCann M J, Kelly WJ, et al. Lactobacillus plantarum MB452 enhances the function of the intestinal barrier by increasing the expression levels of genes involved in tight junction formation. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:316–327. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrieta MC, Bistritz L. Meddings JB. Alterations in intestinal permeability. Gut. 2006;55:1512–1520. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.085373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balda MS. Matter K. Tight junctions at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 2008;121:3677–3682. doi: 10.1242/jcs.023887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balda MS, Whitney JA, Flores C, Gonzalez S, Cereijido M. Matter K. Functional dissociation of paracellular permeability and transepithelial electrical resistance and disruption of the apical-basolateral intramembrane diffusion barrier by expression of a mutant tight junction membrane protein. J. Cell Biol. 1996;134:1031–1049. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.4.1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AJ, Goldsworthy SM, Barnes AA, Eilert MM, Tcheang L, Daniels D, et al. The orphan G protein-coupled receptors GPR41 and GPR43 are activated by propionate and other short chain carboxylic acids. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:11312–11319. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211609200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cario E, Gerken G. Podolsky DK. Toll-like receptor 2 enhances ZO-1-associated intestinal epithelial barrier integrity via protein kinase C. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:224–238. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cario E, Gerken G. Podolsky DK. Toll-like receptor 2 controls mucosal inflammation by regulating epithelial barrier function. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1359–1374. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikayama E, Sekiyama E, Okamoto M, Nakanishi Y, Tsuboi Y, Akiyama K, et al. Statistical indices for simultaneous large-scale metabolite detections for a single NMR spectrum. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:1653–1658. doi: 10.1021/ac9022023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Date Y, Sakata K. Kikuchi J. Chemical profiling of complex biochemical mixtures from various seaweeds. J. Polymer. 2012;44:888–894. [Google Scholar]

- De Vrese M. Schrezenmeir J. Probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 2008;111:1–66. doi: 10.1007/10_2008_097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donato KA, Gareau MG, Wang YJJ. Sherman PM. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG attenuates interferon-γ and tumour necrosis factor-α-induced barrier dysfunction and pro-inflammatory signaling. Microbiology. 2010;156:3288–3297. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.040139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elamin EE, Masclee AA, Dekker J, Pieters HJ. Jonkers D M. Short-chain fatty acids activate AMP-activated protein kinase and ameliorate ethanol-induced intestinal barrier dysfunction in Caco-2 cell monolayers. J. Nutr. 2013;143:1872–1881. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.179549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewaschuk JB, Diaz H, Meddings L, Diederichs B, Dmytrash A, Backer J, et al. Secreted bioactive factors from Bifidobacterium infantis enhance epithelial cell barrier function. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2008;295:G1025–G1034. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90227.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrier L, Berard F, Debrauwer L, Chabo C, Langella P, Bueno L, et al. Impairment of the intestinal barrier by ethanol involves enteric microflora and mast cell activation in rodents. Am. J. Pathol. 2006;168:1148–1154. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050617. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz CMAP, Huch M, Abriouel H, Holzapfel W. Gálvez A. Enterococci as probiotics and their implications in food safety. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2011;151:125–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galdeano CM. Perdigon G. The probiotic bacterium Lactobacillus casei induces activation of the gut mucosal immune system through innate immunity. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13:219–226. doi: 10.1128/CVI.13.2.219-226.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groschwitz KR. Hogan SP. Intestinal barrier function: molecular regulation and disease pathogenesis. J Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009;124:3–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He F, Peng J, Deng XL, Yang LF, Camara AD, Omran A, et al. Mechanisms of tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced leaks in intestine epithelial barrier. Cytokine. 2012;59:264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoarau C, Lagaraine C, Martin L, Velge-Roussel F. Lebranchu Y. Supernatant of Bifidobacterium breve induces dendritic cell maturation, activation, and survival through a Toll-like receptor 2 pathway. J. Allergy Clin. Immun. 2006;117:696–702. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.10.043. , and . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laukoetter MG, Bruewer M. Nusrat A. Regulation of the intestinal epithelial barrier by the apical junctional complex. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2006;22:85–89. doi: 10.1097/01.mog.0000203864.48255.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma TY, Boivin MA, Ye D, Pedram A. Said HM. Mechanism of TNF-α modulation of Caco-2 intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier: role of myosin light-chain kinase protein expression. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2005;288:G422–G430. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00412.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma TY, Iwamoto GK, Hoa NT, Akotia V, Pedram A, Boivin MA, et al. TNF-α-induced increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability requires NF-κB activation. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G496–G504. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00173.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Torbenson M, Hamad AR, Soloski MJ. Li Z. High-fat diet modulates non-CD1d-restricted natural killer T cells and regulatory T cells in mouse colon and exacerbates experimental colitis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2008;151:130–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03530.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malago JJ, Koninkx JF, Douma PM, Dirkzwager A, Veldman A, Hendriks HG, et al. Differential modulation of enterocyte-like Caco-2 cells after exposure to short-chain fatty acids. Food Addit. Contam. 2003;20:427–437. doi: 10.1080/0265203031000137728. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloy KJ. Powrie F. Intestinal homeostasis and its breakdown in inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2011;474:298–306. doi: 10.1038/nature10208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchiand AM, Graham WV. Turner JR. Epithelial barriers in homeostasis and disease. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2010;5:119–144. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariadason JM, Barkla DH. Gibson PR. Effect of short-chain fatty acids on paracellular permeability in Caco-2 intestinal epithelium model. Am. J. Physiol. 1997;272:G705–G712. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.4.G705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyauchi E, Morita H, Okuda J, Sashihara T, Shimizu M. Tanabe S. Cell wall fraction of Enterococcus hirae ameliorates TNF-α-induced barrier impairment in the human epithelial tight junction. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2008;46:469–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02332.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyauchi E, Morita H. Tanabe S. Lactobacillus rhamnosus alleviates intestinal barrier dysfunction in part by increasing expression of zonula occludens-1 and myosin light-chain kinase in vivo. J. Dairy Sci. 2009;92:2400–2408. doi: 10.3168/jds.2008-1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyauchi E, O'Callaghan J, Buttó LF, Hurley G, Melgar S, Tanabe S, et al. Mechanism of protection of transepithelial barrier function by Lactobacillus salivarius: strain dependence and attenuation by bacteriocin production. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G1029–G1041. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00003.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamadzadeh M, Olson S, Kalina WV, Ruthel G, Demmin GL, Warfield KL, et al. Lactobacilli activate human dendritic cells that skew T cells toward T helper 1 polarization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:2880–2885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500098102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noth R, Stüber E, Häsler R, Nikolaus S, Kühbacher T, Hampe J, et al. Anti-TNF-α antibodies improve intestinal barrier function in Crohn's disease. J. Crohns. Colitis. 2012;6:464–469. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Hara JR. Buret AG. Mechanism of intestinal tight junctional disruption during infections. Front Biosci. 2008;112:266–274. doi: 10.2741/3206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohland CL. MacNaughton WK. Probiotic bacteria and intestinal epithelial barrier function. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2010;298:G807–G819. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00243.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshima T, Miwa H. Joh T. Aspirin induces gastric epithelial barrier dysfunction by activating p38 MAPK via claudin-7. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C800–C806. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00157.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel RM, Myers LS, Kurundkar AR, Maheshwari A, Nusrat A. Lin PW. Probiotic bacteria induce maturation of intestinal claudin 3 expression and barrier function. Am. J. Pathol. 2012;180:626–635. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putaala H, Salusjarvi T, Nordstrom M, Saarinen M, Ouwehand AC, Bech Hansen E, et al. Effect of four probiotic strains and Escherichia coli O157:H7 on tight junction integrity and cyclooxygenase expression. Res. Microbiol. 2008;159:692–698. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resta-Lenert S. Barrett KE. Live probiotics protect intestinal epithelial cells from the effects of infection with enteroinvasive Escherichia coli (EIEC) Gut. 2003;52:988–997. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.7.988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resta-Lenert S. Barrett KE. Probiotics and commensals reverse TNF-α- and IFN-γ-induced dysfunction in human intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:731–746. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L, Black ED, Witkowski ED, Lencer WI, Guerriero V, Schneeberger EE, et al. Myosin light chain phosphorylation regulates barrier function by remodeling tight junction structure. J. Cell Sci. 2006;119:2095–2106. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steck N, Hoffmann M, Sava IG, Kim SC, Hahne H, Tonkonogy SL, et al. Enterococcus faecalis metalloprotease compromises epithelial barrier and contributes to intestinal inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:959–971. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suenaert P, Bulteel V, Lemmens L, Noman M, Geypens B, Van Assche G, et al. Anti-tumor necrosis factor treatment restores the gut barrier in Crohn's disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2000–2004. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultana R, McBain AJ. O'Neill CA. Strain-dependent augmentation of tight-junction barrier function in human primary epidermal keratinocytes by Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium Lysates. Appl. Enviorn. Microbiol. 2013;79:4887–4894. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00982-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T, Yoshida S. Hara H. Physiological concentrations of short-chain fatty acids immediately suppress colonic epithelial permeability. Br. J. Nutr. 2008;100:297–305. doi: 10.1017/S0007114508888733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Targan SR, Hanauer SB, van Deventer SJ, Mayer L, Present DH, Braakman T, et al. A short-term study of chimeric monoclonal antibody cA2 to tumor necrosis factor α for Crohn's disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997;337:1029–1035. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199710093371502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukita S. Furuse M. Claudin-based barrier in simple and stratified cellular sheets. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2002;14:531–536. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00362-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JR, Rill BK, Carlson SL, Carnes D, Kerner R, Mrsny RJ, et al. Physiological regulation of epithelial tight junctions is associated with myosin light-chain phosphorylation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 1997;273:C1378–C1385. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.C1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulluwishewa D, Anderson RC, McNabb WC, Moughan PJ, Wells JM. Roy NC. Regulation of tight junction permeability by intestinal bacteria and dietary components. J. Nutr. 2011;141:769–776. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.135657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Deventer SJ. Tumor necrosis factor and Crohn's disease. Gut. 1997;40:443–448. doi: 10.1136/gut.40.4.443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Itallie CM. Anderson JM. Claudins and epithelial paracellular transport. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2006;68:403–429. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040104.131404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura MT, Polimeno L, Amoruso AC, Gatti F, Annoscia E, Marinaro M, et al. Intestinal permeability in patients with adverse reactions to food. Dig. Liver Dis. 2006;38:732–736. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser J, Rozing J, Sapone A, Lammers K. Fasano A. Tight junctions, intestinal permeability, and autoimmunity: celiac disease and type 1 diabetes paradigms. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009;1165:195–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04037.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelsang H, Schwarzenhofer M. Oberhuber G. Changes in gastrointestinal permeability in celiac disease. Dig. Dis. 1998;16:333–336. doi: 10.1159/000016886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye D, Ma I. Ma TY. Molecular mechanism of tumor necrosis factor-α modulation of intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G496–G504. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00318.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeuthen LH, Fink LN. Frøkiaer H. Toll-like receptor 2 and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-2 play divergent roles in the recognition of gut-derived lactobacilli and bifidobacteria in dendritic cells. Immunology. 2008;124:489–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02800.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zolotarevsky Y, Hecht G, Koutsouris A, Gonzalez DE, Quan C, Tom J, et al. A membrane-permeant peptide that inhibits MLC kinase restores barrier function in in vitro models of intestinal disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:163–172. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zyrek AA, Cichon C, Helms S, Enders C, Sonnenborn U. Schmidt MA. Molecular mechanisms underlying the probiotic effects of Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 involve ZO-2 and PKC zeta redistribution resulting in tight junction and epithelial barrier repair. Cell. Microbiol. 2007;9:804–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]