Abstract

Context

Printers and photocopiers release respirable particles into the air. Engineered nanomaterials (ENMs) have been recently incorporated into toner formulations but their potential toxicological effects have not been well studied.

Objective

To evaluate the biologic responses to copier-emitted particles in the lungs using a mouse model.

Methods

Particles from a university copy center were sampled and fractionated into three distinct sizes, two of which (PM0.1 and PM0.1–2.5) were evaluated in this study. The particles were extracted and dispersed in deionized water and RPMI/10% FBS. Hydrodynamic diameter and zeta potential were evaluated by dynamic light scattering. The toxicologic potential of these particles was studied using 8-week-old male Balb/c mice. Mice were intratracheally instilled with 0.2, 0.6, 2.0 mg/kg bw of the PM0.1 and PM0.1–2.5 size fractions. Fe2O3 and welding fumes were used as comparative materials, while RPMI/10% FBS was used as the vehicle control. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed 24 hours post-instillation. The BAL fluid was analyzed for total and differential cell counts, and biochemical markers of injury and inflammation.

Results

Particle size- and dose-dependent pulmonary effects were found. Specifically, mice instilled with PM0.1 (2.0 mg/kg bw) had significant increases in neutrophil number, lactate dehydrogenase and albumin compared to vehicle control. Likewise, pro-inflammatory cytokines were elevated in mice exposed to PM0.1 (2.0 mg/kg bw) compared to other groups.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that exposure to copier-emitted nanoparticles may induce lung injury and inflammation. Further exposure assessment and toxicological investigations are necessary to address this emerging environmental health pollutant.

Keywords: nanoparticles, printers, photocopiers, inflammation, lung injury

INTRODUCTION

The use of photocopying equipment has increased dramatically, with 1.1 million copiers sold per year in the United States (Stewart, 2007). Currently, printers and photocopiers are an integral part of the office and home environments. According to a report by Photizo Group (Jamieson, 2012), more than 50% of medium-sized businesses in the US bought more than 11 black toner cartridges in 2011. This widespread use of photocopying equipment increases the likelihood of exposures of large populations, including susceptible individuals.

There are reports on emissions from printing and photocopying equipment indicating the presence of a complex mixture, which includes particulates, ozone and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) (Wensing et al., 2006, Lee and Hsu, 2007, Morawska et al., 2009, Tang et al., 2012b). Metals such as titanium, iron, chromium, nickel, and zinc have also been found in printer toners in relatively significant amounts (Barthel et al., 2011). Furthermore, copier-emitted particle concentrations in under-ventilated office spaces have been reported to reach levels of up to 1×108 particles/cm3 (Lee and Hsu, 2007), thus increasing the risk of inhalation exposures and suggesting a need for a proper toxicological assessment of this exposure.

Recently, photocopier and printer exposures have gained more attention due to the incorporation of engineered nanoparticles (ENP) in the toner formulations to improve product quality (Bello et al., 2012). This shift from the micron to nano size materials in toner formulations raises questions in terms of changes in the physicochemical properties of emitted PM and their toxicological profile. However, very few published exposure and toxicological studies have focused on realistic emitted PM. Little is known about the potential health effects from ENPs incorporated into toners.

There is extensive evidence linking exposures to atmospheric PM2.5 (particles with an aerodynamic diameter less than 2.5 µm) to increased mortality and morbidity due to cardiovascular and respiratory diseases (Dockery et al., 1993, Dominici et al., 2006, Zhao et al., 2013, Perrone et al., 2013). The toxicological evidence related to copier-emitted PM continues to grow, but it remains inconclusive. Animal studies report that toner powders, if used at high concentrations, cause chronic inflammation and fibrosis, as well as the onset of tumors in the lung (Moller et al., 2004, Mohr et al., 2005, Mohr et al., 2006, Bai et al., 2010). However, there is contradicting evidence with regards to tumorigenesis, with other studies reporting no induction of tumors due to inhalation exposure to toner (Morimoto et al., 2005).

In addition to animal studies, several epidemiological reports exist and link employment in photocopy centers with genotoxicity. For instance, one study showed there was extensive oxidative and DNA damage, as measured by the micronuclei and Comet assays, in buccal and white blood cells of photocopier operators. The damage was directly proportional to the time operators spent at work (Kleinsorge et al., 2011). Moreover, several recent studies on cohorts of photocopy employees have found elevated biomarkers of DNA damage compared with controls (Goud et al., 2004, Patel et al., 2005, Balakrishnan and Das, 2010, Manikantan et al., 2010). Likewise, (Khatri et al., 2012) reported a 2–10 fold increase in several cyto- and chemokines, total protein and neutrophils in the nasal lavage fluid, as well as 8-OHdG, a marker of oxidative DNA damage, in the urine of healthy volunteers following a single day exposure to copier-emitted particles at modest exposures. These biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress remained elevated for up to 36 hours. In contrast, (Yang and Haung, 2008) reached different conclusions after performing a cross-sectional study of photocopier workers in Taiwan, where it was found that current employment in photocopying (<3 years) was not linked to either chronic respiratory or acute irritative symptoms, assessed via questionnaires. No actual exposure measurements were conducted in that study and no information was provided with regards to engineering controls or hygiene conditions; moreover air pollution may serve as a confounder of such effects.

We note that most of the published toxicological studies on this topic have been conducted using toner powders rather than copier-emitted PM (Lin, 1994, Slesinski and Turnbull, 2008, Gminski et al., 2011, Konczol et al., 2013). Some of the earlier literature discrepancies may be explained by differences in the chemical composition of PM used, which has gone unnoticed because of incomplete chemical characterization, or from the use of toner powders, rather than realistically emitted PM, and because of other confounding environmental factors (e.g., air pollution).

Our group has recently completed a physicochemical and morphological characterization of PM generated during the photocopying process in a university copy center (Bello et al., 2012). Different size fractions of airborne PM were collected and characterized, including PM0.1, PM0.1–2.5 and PM2.5–10. The study confirmed the presence of ENPs in the toner formulation as well as its chemical complexity in both the toner and the emissions. The elemental composition of the emitted PM included iron, titanium, manganese, zinc, aluminum, and silicon. Elements such as nickel, chromium, manganese and titanium were found in single particle analysis by transmission electron microscopy and energy dispersive spectroscopy. Most metals, including iron, manganese, and zinc, were found to have higher water solubility in the emitted PM than in the toner sample itself. Moreover, a large fraction of the emitted PM was comprised of organic carbon, which made up 50–70% of the total mass.

Here, we sought to further expand on recent human and in vitro toxicological studies (Bello et al., 2012, Khatri et al., 2012, Khatri et al., 2013a, Khatri et al., 2013b) our colleagues reported on a particular university copy center, and complement them by studying the effects of emitted PM in the lungs, especially in the small airways and lung parenchyma. We have taken an in vivo experimental approach using an animal model to assess the effect of different size fractions of copier-emitted PM (PM0.1 and PM0.1–2.5) on lung biology.

METHODS

Size-fractionated PM from a university copy center was collected and physicochemically and morphologically evaluated post sampling (Bello et al., 2012). PM0.1 and PM0.1–2.5 size fractions were extracted, dispersed and characterized in a liquid suspension following the protocol described in (Cohen et al., 2012). Eight-week old male Balb/c mice were then divided into 5 exposure groups (n = 5–12 mice/group) and intratracheally instilled with PM0.1, PM0.1–2.5, Fe2O3, welding fumes or RPMI/10% FBS (vehicle control). Multiple doses were used (0.20, 0.60 and 2.0 mg/kg body weight). Twenty-four hours post instillation, bronchoalveolar lavage was performed on the mice and the lavage fluid was analyzed for lactate dehydrogenase, myeloperoxidase, albumin and hemoglobin levels, as well as white blood cell count and pro-inflammatory cyto- and chemokine expression in order to assess the impact of copy center particle exposure.

Sampling and preparation of size-fractionated airborne PM

Collection and characterization of airborne PM

Sampling was performed at a university photocopy center during work hours (7 AM – 3 PM) with two high-volume monochrome photocopy machines as described by (Bello et al., 2012). In summary, real-time monitoring for size distribution and total number concentration was performed using a Fast Mobility Particle Sizer (FMPS Model 3091, TSI Inc.) and an Aerodynamic Particle Sizer (APS Model 3321, TSI Inc.). Size-selective PM sampling was performed using the Harvard Compact Cascade Impactor (CCI), which collected particles in three stages corresponding to PM0.1, PM0.1–2.5 and PM2.5–10 (Demokritou et al., 2004). The PM mass on each stage was determined gravimetrically as the difference between post- and pre-weight of the collection media following 24–48 hours of equilibration in a temperature- and relative humidity-controlled chamber using a high sensitivity analytical balance (Mettler-Toledo) with a 0.1 µg resolution. The airborne PM collected from the photocopy center is a combination of emissions from the photocopiers as well as PM from other possible indoor sources and ambient particles infiltrating indoors. Separation of these sources was not possible in the present study. However, based on real time monitoring the ratio of long-term average particle number concentration in the photocopy center to that of indoor background is estimated to be 10–15 times, with the estimated indoor background aerosol contribution to be 5–10% (Bello et al., 2012, Khatri et al., 2012).

Post sampling physicochemical and morphological analysis of airborne PM

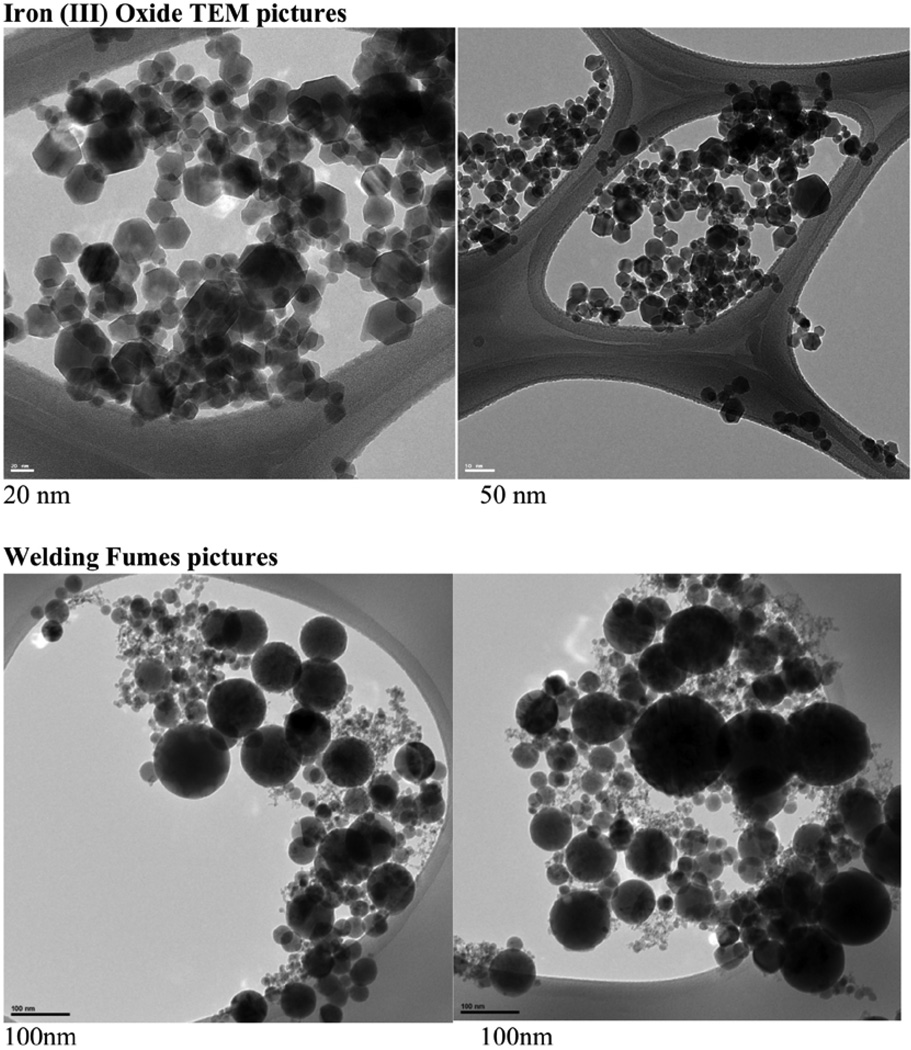

Detailed physicochemical characterization for each PM size fraction is reported in a recent publication (Bello et al., 2012). In summary, chemical analysis of PM0.1, PM0.1–2.5 and PM2.5–10 included magnetic-sector (SF) field inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (SF-ICP-MS) for the total and water-soluble fraction of multiple metals (50 elements), gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) of 150 sVOCs species, organic and elemental carbon, as well as single particle morphological and elemental analysis. Morphological analysis of the collected airborne PM, as well as the Fe2O3 and welding fume particles, was performed using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) imaging (TEM/EDS, Philips EM 400T).

Extraction of sampled PM

After collecting the size fractionated PM samples, the Teflon filter containing the PM0.1 size fraction and the polyurethane foam (PUF) containing PM0.1–2.5 were removed from the CCI and the collected particles extracted from the substrates using an aqueous suspension methodology as described in (Lough et al., 2005). The Teflon filter was submerged in a beaker containing 10–15 mL of deionized water (DI H2O), such that the side containing the particles faced the bottom of the beaker. The filters were then sonicated for one hour using a Branson bath sonicator model 1510 (Branson Ultrasonics, Danbury, CT). Afterward, the samples were sonicated with a Branson Sonifier S-450A (Branson Ultrasonics, Danbury, CT) fitted with a 3-inch cup horn (maximum power output of 400 Watts at 60 Hz) for 1 minute at 30% amplitude, with a 10-second cycle. As for the PUF containing the PM0.1–2.5 size fraction, it was placed in a scintillation vial containing 4 mL of DI H2O and placed in a water bath for 20–30 minutes. The vial was then transferred to a Branson Sonifier S-450A cup sonicator (Branson Ultrasonics, Danbury, CT) for 2–3 minutes at 30% amplitude with a 10-second cycle. Lastly, the dispersed particle solutions were evaporated down to 1 mL using nitrogen. Extraction efficiency of particles from the filter media, determined by weight difference, was 80 and 92% for the PM0.1–2.5 and PM0.1, respectively. It must be noted that only the extracted particles were evaluated in this study.

Sampled PM dispersion and characterization in liquid suspension

Particle dispersions were prepared using a protocol previously described (Cohen et al., 2012). It included the calibration of sonication equipment, standardized reporting of sonication energy, and characterization of the critical delivered sonication energy (DSEcr) for each collected PM size fraction. In brief, dispersions were sonicated with a Branson Sonifier S-450A (Branson Ultrasonics, Danbury, CT), which had been calibrated by the calorimetric calibration method (Taurozzi et al., 2010, Cohen et al., 2012), whereby the power delivered to the sample was determined to be 1.75 Watts. Dispersions were then analyzed for hydrodynamic diameter (dH), polydispersity index (PdI), zeta potential (ζ) and, specific conductance (σ) by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using the Zetasizer Nano-ZS (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK). The pH was also measured using a VWR sympHony pH meter (VWR International, Radnor, PA, USA). Plots of the hydrodynamic diameter as a function of DSE exhibiting asymptotic deagglomeration trends were derived for each ENM to determine the critical DSE necessary to achieve monodisperse suspensions that were stable over time. Once the DSEcr was characterized and applied to each sample, the stock particle solutions in DI H2O were then diluted to desired concentrations in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) cell culture media supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, and 10 mM HEPES and vortexed for 30 seconds. The PM suspensions in RPMI/10%FBS were characterized for various particle and media parameters by DLS and used to intratracheally instill animals for toxicological evaluation as described below. It is worth mentioning that RPMI/10% FBS was used as the vehicle in order to allow for proper comparison of in vitro and in vivo results

Material controls

Two materials were used as comparative/control materials, welding fumes and Fe2O3. The gas metal arc-mild steel welding fumes were provided by Dr. J. Antonini from the National Institute for Occupational Health (NIOSH) in Morgantown, WV. This sample has been shown to induce toxicity in the lungs of rodents (Zeidler-Erdely et al., 2011, Antonini et al., 2012, Sriram et al., 2012). It was generated as described by (Antonini et al., 1999) and had a count mean diameter of 1.22 microns. The surface area was measured using nitrogen sorption analysis at 77 K using a Quantachrome Autosorb-3B gas physisorption unit [Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method]. Before sorption measurements, the welding fumes sample was degassed for 48 hours at 100 °C. Surface area value was determined from 13-point BET fits of data obtained over a pressure range of P/P0 = 0.05–0.3 (correlation coefficient of 0.9998 for BET fit). The welding fume particles used in this study were found to have an average BET equivalent diameter of 50–60 nm and a surface area of 33.27 m2/g. Iron oxide (Fe2O3) nanoparticles were generated in house using the flame spray pyrolysis based Harvard Versatile Engineered Nanomaterial Generation System (VENGES) (Demokritou et al., 2010, Sotiriou et al., 2012). The Fe2O3 ENPs had an average BET equivalent diameter of 19.6 nm and a specific surface area of 41.50 g/cm3. TEM images of both the welding fumes and Fe2O3 were obtained using a Zebra Libra 120 (Carl Zeiss, Germany) and are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Representative images of the (A) Fe2O3 and (B) welding fumes using transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

In vivo experimental design

Following collection and post sampling extraction and characterization of the PM0.1 and PM0.1–2.5 size fractions, we aimed to evaluate the in vivo biological responses due to exposure via intratracheal instillation. Animal protocols used in this study were approved by the Harvard Medical Area Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Animals

Eight-week-old Balb/c male mice weighing an average of 23.71 grams (SD = 0.67) were purchased from Taconic Farms Inc. (Hudson, NY). Mice were housed in groups of 4 in polypropylene cages and allowed to acclimate for 1 week before the studies were initiated. Mice were maintained on a 12-hour light/dark cycle. Food and water were provided ad libitum.

Intratracheal instillation (IT)

Test materials were prepared shortly prior to each experiment. Each mouse was weighed and the dose was calculated at 2.5 mL/kg body weight (bw). The dosing solution was measured in a sterile syringe with an attached blunt-tipped 21-gauge gavage needle. The mice were anesthetized with vaporized isoflurane, quickly restrained on a slanted board and held upright by their upper incisor teeth resting on a rubber band. As the animals were under anesthesia, the tip of the needle was gently inserted into the trachea between the vocal cords, with the tip just above the tracheal bifurcation, and the dosing suspension was delivered in one bolus. After instillation, the animal was allowed to recover from anesthesia in a slanted position while the thorax was gently massaged to facilitate distribution of the instillate throughout the lungs. The mice received an intratracheal instillation of PM0.1, PM0.1–2.5, Fe2O3, or welding fumes(Sriram et al., 2012) at 0.2, 0.6 and 2.0 mg/kg bw. RPMI/10% FBS was used as vehicle control. In order to relate the IT doses used in this study to airborne PM exposure dose, which might occur in copier rooms the Multiple Path Particle Deposition model (MPPD2) was used to calculate the mass deposition in a rodent lung (Anjilvel and Asgharian, 1995) for a 24 hour exposure. For the worst case scenario published in the literature with a particle number concentrations of 1 × 10 E8 particles/cm3 (Lee and Hsu, 2007) the model estimated a total particle deposited mass of 1.508 mg, which is equivalent to a dose of 50.27 mg/kg for a rodent weighing 30 grams.

For exposure levels observed in this copy center of 1.2×10E6 (Bello et al., 2012), the MPDD model estimated a total particle deposited mass of 0.695 mg, which is equivalent to a dose of 0.695 mg/kg for a rodent weighing 30 grams

The IT doses used in this study vary from 0.2 to 2 mg/kg and are significantly less than the extreme exposure value but in line with the exposure levels associated with this particular copy center.

Bronchoalveolar lavage and analyses

Twenty-four hours after intratracheal instillations, mice were anaesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of FatalPlus (0.1–0.2 mL), and sacrificed by exsanguination, followed by bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). The lungs were lavaged in situ with 12 washes of 0.75 mL of sterile 0.9% saline. The first two washes were pooled for biochemical assays. Cells were separated from the supernatant in all washes (400 × g at 40 °C for 10 minutes). Total and differential cell counts, as well as hemoglobin measurements were made from the cell pellets. Total cell counts were performed manually using a hemocytometer. Cell smears were made with a cytocentrifuge (Shandon Southern Instruments, Inc., Sewickley, PA) and stained with Diff-Quick (American Scientific Products, McGaw Park, IL). Differential cell counts were performed by counting 200 cells per mouse. The supernatant fraction of the first two washes was clarified by sedimentation at 15 000 × g for 30 minutes and used for measurement of enzyme activity, albumin and cytokine measurements. Standard spectrophotometric assays were used for lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), myeloperoxidase (MPO), albumin, and hemoglobin (Hb) to identify damage to the lungs as described in (Beck et al., 1982).

Multiplex cytokine analysis

Cytokine levels in BAL fluid were measured by Eve Technologies Corporation (Calgary, Alberta, Canada) using a MILLIPLEX Mouse Cytokine/Chemokine 32-plex kit (Millipore, St. Charles, MO, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The 32-plex consisted of eotaxin, G-CSF, GM-CSF, IFN-gamma, IL-1alpha, IL-1beta, IL-2, IL-3, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-9, IL-10, IL-12 (p40), IL-12 (p70), IL-13, IL-15, IL-17, IP-10, KC, LIF, LIX, MCP-1, M-CSF, MIG, MIP-1alpha, MIP-1beta, MIP-2, RANTES, TNF-alpha, and VEGF. The sensitivities of the assay to these markers range from 0.3–63.6 pg/mL.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (La Jolla, CA). Comparisons between all bronchoalveolar lavage fluid parameters after exposure to PM0.1, PM0.1–2.5, Fe2O3, welding fumes or RPMI/10% FBS were evaluated using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey correction for multiple comparison statistical significance. A p-value of 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Characterization of PM in liquid suspensions

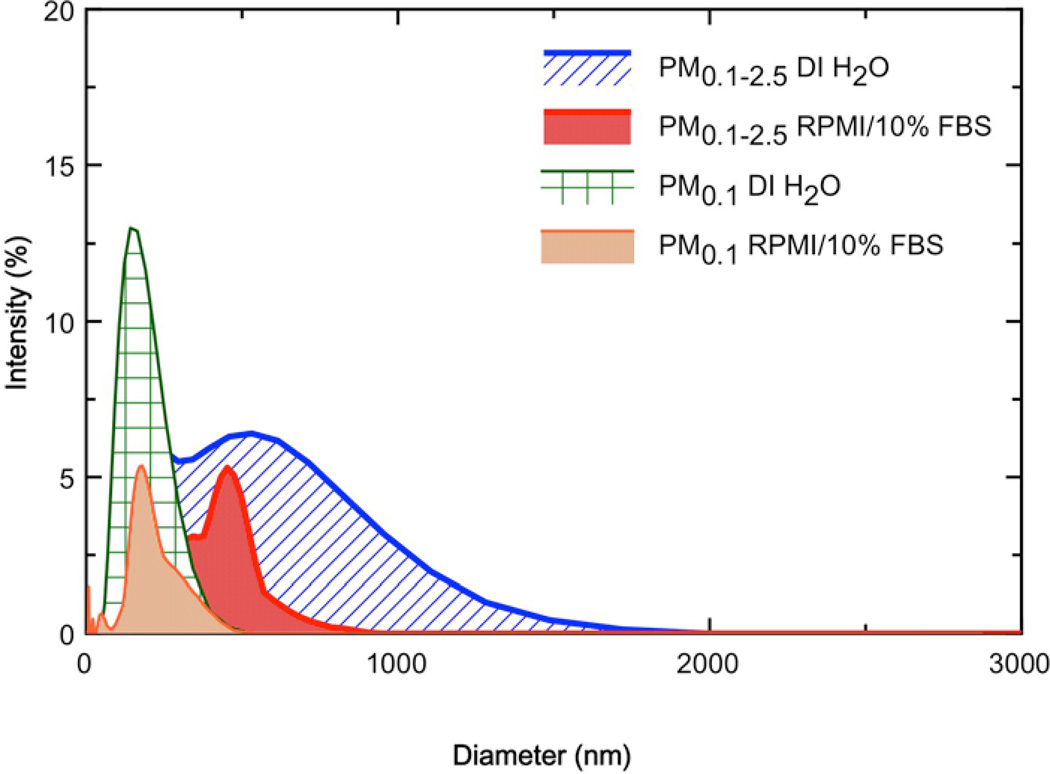

Table 1 summarizes the particle behavior in both DI H2O and cell culture media, as described by hydrodynamic diameter (dH), zeta potential (ζ), polydispersity index (PdI) and specific conductance (σ). Both the PM0.1 and PM0.1–2.5 liquid suspensions showed a decrease in dH as the calculated delivered sonication energy (DSE) increased, toward a horizontal asymptote, representing a marginal state of agglomeration (data not shown). The estimated DSEcr values varied from 161 to 242 J/mL, and required sonication for a period between 15 and 23 minutes at the settings described in the methods section (data not shown). Welding fumes were determined to have a dH of 1379 nm in DI H2O, which was more than twice the diameter of welding fumes dispersed in RPMI/10% FBS. The observed diameter of Fe2O3 dispersed in DI H2O was 163.1 nm and had a PdI of 0.239. Figure 1 shows the size distribution plots for PM0.1 and PM0.1–2.5 dispersed in DI H2O and RPMI/10%FBS. In general, the dH ranged from 150–300 nm, with PM0.1 having smaller agglomerate sizes in both DI H2O and RPMI/10%FBS as compared to PM0.1–2.5. Observed values of ζ were strongly negative for suspensions in DI H2O (~ −35mV), and less negative in RPMI/10% (~−10mV).

Table 1.

Properties of ENM dispersions. dH: hydrodynamic diameter, PdI: polydispersity index, ζ: zeta potential, σ: specific conductance.

| Material | Media | dH (nm) | PdI | ζ (mV) | σ (mS/cm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PM0.1 | DI H2O | 154 ± 2.646 | 0.297 ± 0.015 | −39.1 ± 4.24 | 0.170 ± 0.01 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 206 ± 28.090 | 0.562 ± 0.044 | −11.5 ± 1.11 | 7.58 ± 0.165 | |

| PM0.1–2.5 | DI H2O | 291± 6.612 | 0.410 ± 0.038 | −34.5 ± 9.39 | 0.683 ± 0.152 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 263 ± 9.527 | 0.462 ± 0.063 | −13.6 ± 4.74 | 9.32 ± 1.10 | |

| Fe2O3 | DI H2O | 117.4 ± 4.272 | 0.239 ± 0.009 | 17.8 ± 4.15 | 0.0236 ± 0.0005 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 1656 ± 189.8 | 0.302 ± 0.032 | 8.64 ± 0.887 | 10.3 ± 0.7921 | |

| Welding fumes | DI H2O | 1379 ± 97.87 | 0.414 ± 0.026 | 22.9 ± 2.71 | 0.0206 ± 0.00286 |

| RPMI/10%FBS | 664.8 ± 19.79 | 0.515 ± 0.175 | −9.18 ± 0.555 | 11.9 ± 0.308 |

Notes: Values represent the mean (± SD) of a triplicate reading.

Figure 1. Particle size distributions for dispersions of PM0.1 and PM0.1–2.5 suspended in either DI H2O or RPMI/10%FBS, as measured by DLS.

Copier-emitted particle mediated reduction in membrane integrity and alveolar permeability

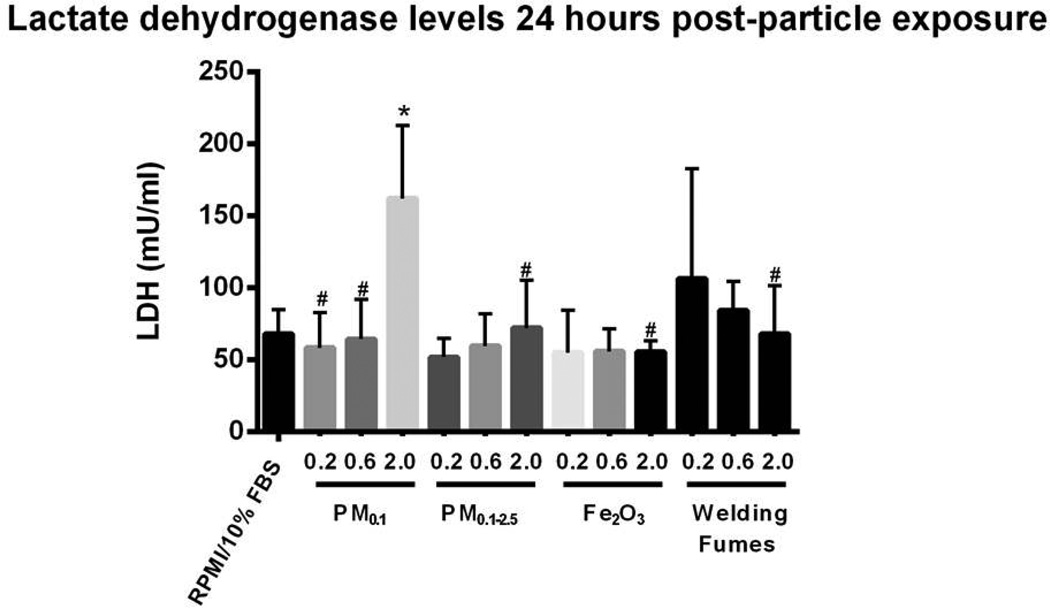

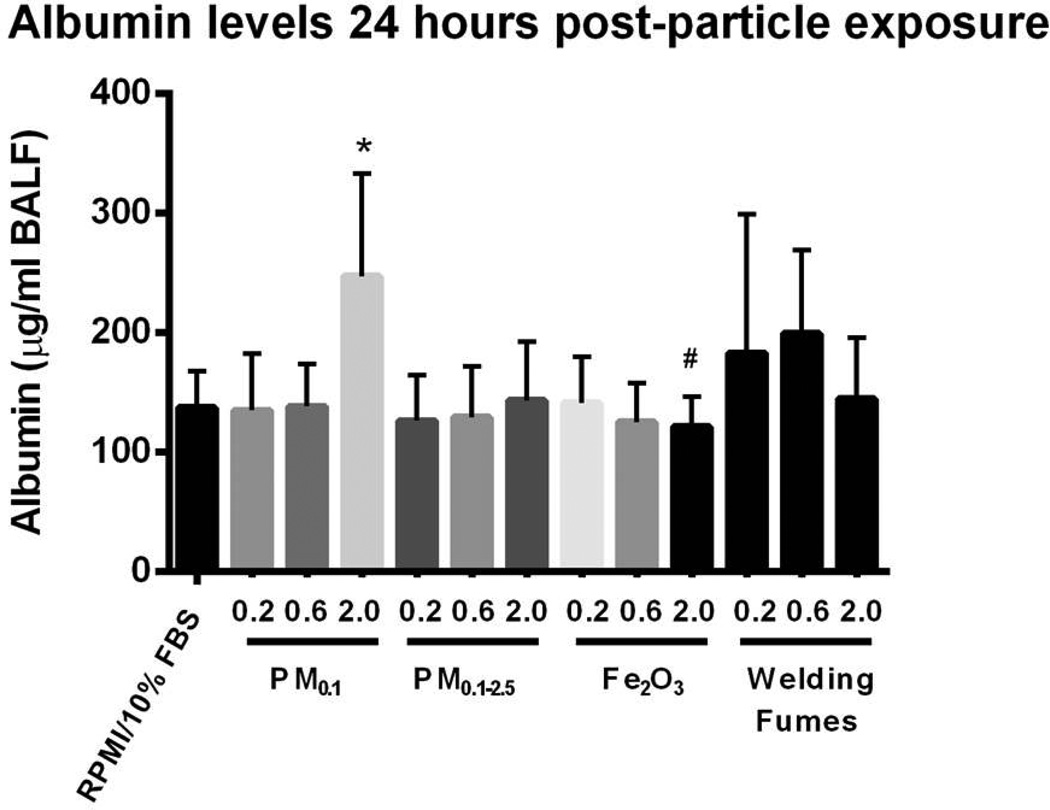

Figure 2 shows LDH levels observed in the BAL fluid of mice for the instilled materials. For the case of the PM0.1 size fraction, LDH followed a dose response relationship and was significantly increased at the dose of 2 mg/kg compared to the other PM0.1 doses (0.2 and 0.6 mg/kg), Fe2O3 (2 mg/kg), welding fumes (2 mg/kg) and vehicle control (p < 0.05). This indicates that there was significantly higher plasma membrane damage after exposure to PM0.1 than the other test materials. Similarly, levels of albumin in BAL fluid after IT exposure to PM0.1 (2 mg/kg) were higher than those after treatment with either vehicle control or dose-matched Fe2O3 (p < 0.05) (Figure 3). There was no statistically significant difference between the levels of myeloperoxidase and hemoglobin across the different exposure groups (data not shown).

Figure 2. Expression of extracellular Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) in BALF after IT exposure.

There is significant plasma membrane damage after exposure to PM0.1 particles emitted from photocopiers. Values are expressed as means (±SD). *p < 0.05 compared to RPMI/10% FBS. #p < 0.05 compared to PM0.1 (2 mg/kg).

Figure 3. Levels of albumin in BALF after IT exposure.

There are significant levels of albumin in BALF after exposure to PM0.1 particles emitted from photocopiers. Values are expressed as means (±SD) *p < 0.05 compared to RPMI/10% FBS. #p < 0.05 compared to PM0.1 (2 mg/kg).

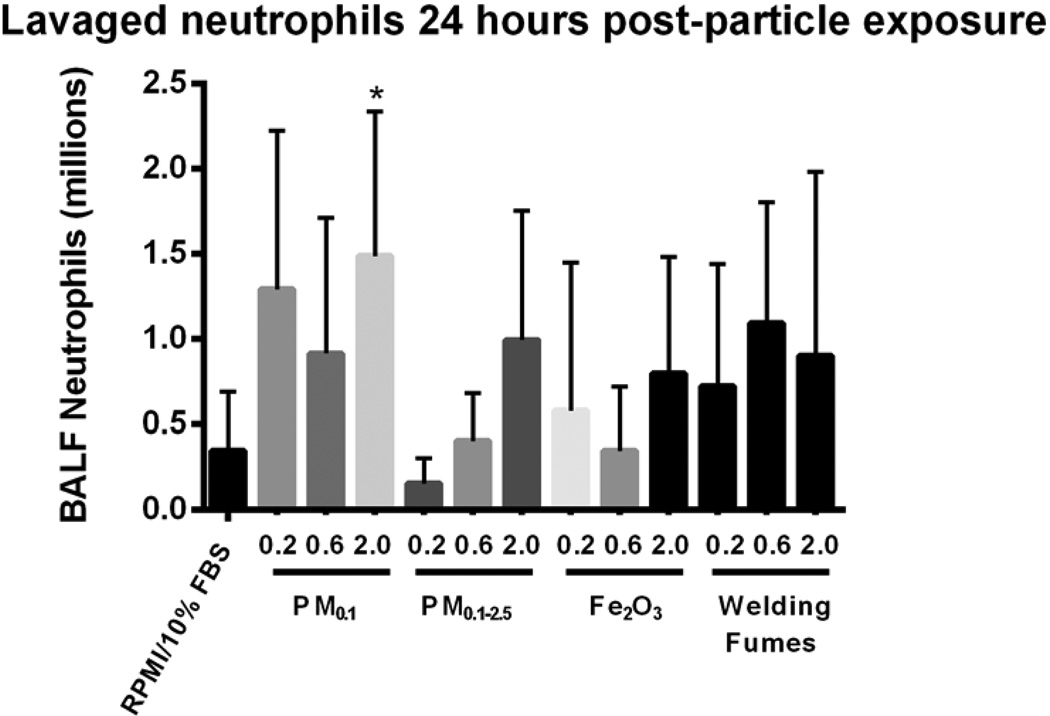

Inflammatory cell response to copier-emitted particles

Figure 4 illustrates the number of neutrophils in murine BAL fluid after exposure to PM0.1 and PM0.1–2.5. The animals exposed to the highest dose (2 mg/kg) of the PM0.1 fraction of copier-emitted particles displayed significant inflammation in the lung, as confirmed by the elevated neutrophil infiltration in BAL fluid, when compared to the vehicle control (p < 0.05). No significant change in the macrophage count in BAL fluid of mice exposed to either the PM0.1 or PM0.1–2.5 size fractions was observed. For PM0.1, an inverse relationship is observed between dose and macrophage number (Table 2).

Figure 4. Number of neutrophils in BALF after IT exposure.

There is a significant inflammation response after exposure to PM0.1 particles emitted from photocopiers. Values are expressed as means (±SD). *p < 0.05 compared to RPMI/10% FBS.

Table 2.

Total and differential white blood cell (WBC) counts recovered in BAL fluid 24 hours post-instillation.

| Group | Mice per group |

WBCs in BALF (millions) |

Macrophag es (millions) |

Neutrophil s (millions) |

Lymphocyte s (millions) |

Eosinophils (millions) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPMI/10%FBS | 12 | 2.96 ± 0.39 | 2.56 ± 0.39 | 0.35 ± 0.10 | 0.05 ± 0. 01 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| PM0.1 | 0.20 mg/kg | 6 | 3.89 ± 0.77 | 2.51 ± 0.67 | 1.29 ± 0.38 | 0.11 ± 0.03 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| 0.60 mg/kg | 6 | 2.73 ± 0.37 | 1.75 ± 0.38 | 0.92 ± 0.33 | 0.07 ± 0.02 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| 2.0 mg/kg | 6 | 2.46 ± 0.50 | 0.92 ± 0.25 | 1.49 ± 0.35* | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| PM0.1–2.5 | 0.20 mg/kg | 9 | 1.82 ± 0.27# | 1.60 ± 0.30 | 0.15 ± 0.05 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| 0.60 mg/kg | 7 | 2.40 ± 0.26 | 1.93 ± 0.28 | 0.40 ± 0.10 | 0.06 ± 0.03 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| 2.0 mg/kg | 8 | 1.97 ± 0.36 | 0.91 ± 0.09 | 0.99 ± 0.27 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| Fe2O3 | 0.20 mg/kg | 6 | 3.70 ± 0.45 | 3.08 ± 0.64 | 0.58 ± 0.35 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| 0.60 mg/kg | 6 | 3.55 ± 0.66 | 3.12 ± 0.60 | 0.35 ± 0.15 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| 2.0 mg/kg | 6 | 3.78 ± 0.69 | 2.86 ± 0.73 | 0.80 ± 0.28 | 0.11 ± 0. 06 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| Welding fumes | 0.20 mg/kg | 9 | 1.67 ± 0.16# | 0.92 ± 0.19a | 0.72 ± 0.24 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 |

| 0.60 mg/kg | 6 | 1.98 ± 0.06 | 0.87 ± 0.29a | 1.09 ± 0.29 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

| 2.0 mg/kg | 5 | 1.92 ± 0.33 | 1.00 ± 0.19 | 0.90 ± 0.48 | 0.02 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | |

Notes: Values are expressed as means (±SEM).

p < 0.05 compared to RPMI/10% FBS.

p < 0.05 compared to PM0.1 (0.2 mg/kg).

p < 0.05 compared to dose-matched Fe2O3.

In contrast, exposure to Fe2O3 at 0.2 and 0.6 mg/kg resulted in a significant increase of macrophages when compared to the dose-matched exposure to welding fumes (p < 0.05) (Table 2). As for lymphocyte, eosinophil and basophil numbers, there were no differences among any of the exposure groups (data not shown). The total lavaged cell count 24 hours post IT was significantly elevated in BAL fluid of mice exposed to 0.2 mg/kg of PM0.1 when compared to the dose-matched PM0.1–2.5 and welding fumes groups (p < 0.05) (Table 2).

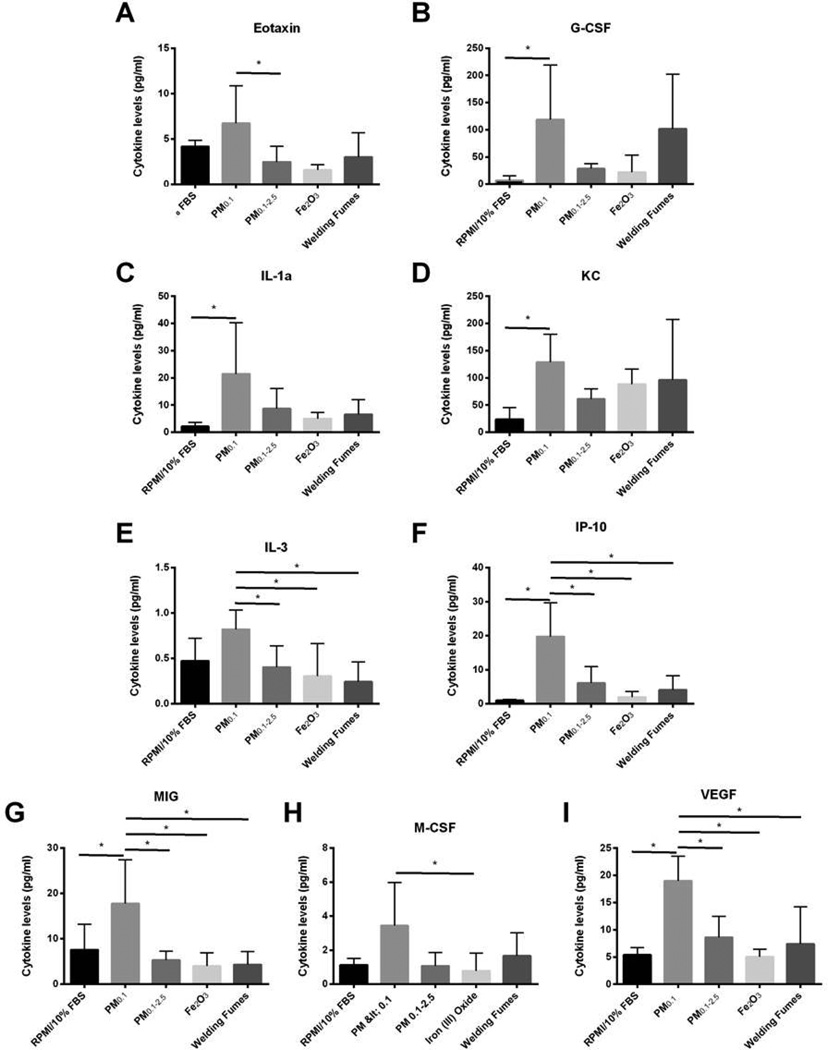

Modulation of cytokine expression due to copier-emitted particle exposures

To accurately assess lung injury, we analyzed the concentration of cytokines involved in the promotion of inflammation in the lung after exposure to the PM0.1 and PM0.1–2.5 size fractions at a dose of 2 mg/kg bw. Of 32 cytokines/chemokines, nine of them, namely eotaxin, granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), interleukin (IL)-1alpha, keratinocyte chemoattractant (KC), IL-3, interferon gamma-induced protein 10 (IP-10), monokine-induced by gamma interferon (MIG), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and macrophage-colony stimulating factor (M-CSF), were increased. They are shown in Figure 5. Levels of eotaxin were significantly higher in the PM0.1 exposure group than in PM0.1–2.5 (p < 0.05) (Figure 5A). Furthermore, levels of G-CSF, IL-1alpha and KC in the BAL fluid were elevated in the PM0.1 exposure group when compared to the vehicle control group (p < 0.05) (Figures 5B–D). Levels of IL-3 significantly increased in murine BAL fluid after exposure to PM0.1 when compared to the PM0.1–2.5, Fe2O3, and welding fumes but not to the vehicle control group (p < 0.05) (Figure 5E). Similar results were observed with IP-10, MIG and VEGF, which were significantly increased in mice BAL fluid after exposure to PM0.1 when compared to the larger counterpart PM0.1–2.5, Fe2O3, welding fumes and vehicle control (p < 0.05) (Figures 5F, G, I). Lastly, an increase in M-CSF levels was observed in the PM0.1 exposure group when compared to the Fe2O3 treatment group (p < 0.05) (Figure 5H). In summary, exposure to copier-emitted PM0.1 led to significantly elevated cytokine levels when compared to the larger counterpart PM0.1–2.5. Moreover, this effect is markedly stronger than that of the welding fumes.

Figure 5. Exposure to copier-emitted particles leads to increased levels of (A) Eotaxin, (B) G-CSF, (C) IL-1a, (D) KC, (E) IL-3, (F) IP-10, (G) MIG, (H) M-CSF and, (I) VEGF.

Values are expressed as means (±SD). * Statistically significant between the groups (p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to assess the acute effects of inhaled copier emitted PM on the lungs using a mouse experimental model. Our results indicated that instilled PM0.1 was able to incite inflammation within the mouse lung at all test concentrations as indicated by the production of several pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines. This investigation is part of a series of studies by our group that aims to evaluate the physico-chemical and toxicological properties of PM emitted from a university photocopier center across different bioassay systems (Bello et al., 2012, Khatri et al., 2012, Khatri et al., 2013a, Khatri et al., 2013b).

In this in vivo investigation some of the results from the aforementioned studies were confirmed. In summary, it was shown here, that instilled PM0.1 was able to incite inflammation within the mouse lung at all test concentrations, evidenced by production of several pro-inflammatory cytokines/chemokines. This size fraction also negatively affected cell membrane integrity, thus increasing lung permeability, as measured by significant levels of albumin and LDH in the murine BAL fluid. Furthermore, the results described in this study suggest that the size of the emitted PM as well as the dose of exposure, are determinants of lung injury. Moreover, the toxicity associated with acute exposure to emitted PM sampled from this particular photocopy center is higher than that of welding fumes, which is a familiar occupational hazard. In more detail:

Cell viability analyses revealed that exposure to PM0.1 at the highest dose induced a 2.4-fold increase in LDH and a 2-fold increase in albumin concentration in contrast to of the comparative materials (welding fumes). LDH is an indicator of cellular membrane damage and presence of albumin in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid suggests lung tissue permeability. Taken together, elevated amounts of LDH and albumin in murine BAL fluid suggest reduced membrane capacity and increased microvascular permeability and leakage. Even though there was no dose-dependent effect, there is clearly a difference in LDH and albumin levels between exposure to PM0.1 and PM0.1–2.5. It is worth noting that (Furukawa et al., 2002) found no change in LDH levels after exposing alveolar macrophages to photocopier toner at various doses (20, 40 and 60 µg/ml). Such a contradiction in results could be explained by the difference in exposure material since toner powder and copier emitted PM may have different physico-chemical properties due to the transformation toner particles go through in the photocopying process.

In addition to elevated markers of cell viability and alveolar permeability, a significantly higher amount of neutrophils was found in BAL fluid of mice exposed to PM0.1 than those instilled with the vehicle control and the other comparative materials. Neutrophils are key players in systemic inflammatory response post-exposure to a foreign substance. Therefore, a substantial increase in neutrophil population indicates an adverse biological response to this size fraction.

Macrophages also act as the first line of defense to foreign pathogens and particles and are able to signal other inflammatory cells to the site of damage, in this case the lung as evidenced by the increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and number of neutrophils in the BAL fluid. Interestingly, in this study, exposure to the two size fractions of copy center particles, at any dose, did not significantly affect the number of collected macrophages from the BALF. We note, however, that there was a substantial increase in the number of lavaged macrophages in mice exposed to Fe2O3 (0.2 and 0.6 mg/kg bw) when compared to the dose-matched welding fumes exposure group. This observed variability in the number of macrophages recovered from the lavage fluid could be explained by the exposure material and the condition of the alveolar macrophages. More specifically, the activation state and level of phagocytic activity can affect the adhesion of alveolar macrophages to the surface, consequently influencing the number of recovered macrophages (Rehn et al., 1992).

Furthermore, in this in vivo investigation, we observed an increase in the concentration of several key inflammatory factors (eotaxin, G-CSF, IL-1alpha, IL-3, IP-10, MIG, VEGF, M-CSF and KC) after exposure to the PM0.1 size fraction. A rise in expression levels of these cytokines and chemokines is a strong indicator of an inflammatory response to a particular exposure and may therefore have an important role in development of many pulmonary diseases. In particular, eotaxin is a chemokine synthesized by airway smooth muscle cells in response to tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha and IL-1beta release and has been associated with inflammatory diseases such as asthma, where airway smooth muscle cells are hyper proliferative and hence increase eotaxin expression (Chung et al., 1999, Johnson et al., 2001, Chang et al., 2012).

The levels of IL-1alpha, a critical inflammatory mediator, were also significantly affected by exposure to the highest dose of PM0.1. Similar results were obtained in an in vitro study by (Yazdi et al., 2010), which showed that intraperitoneal injection of titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles (20 or 80 nm in diameter) to mice can induce release of IL-1alpha by activation of the NOD-like receptor pyrin domain containing 3 (Nlrp3) inflammasome and consequently, cause pulmonary inflammation. Furthermore, a transient increase in levels of IL-1alpha was observed in rats after IT of 0.2 mg of nickel oxide nanoparticles (mass median diameter of 26 nm) in a study by (Morimoto et al., 2010).

The role of VEGF has also been studied extensively since it is an important growth factor associated with the development of many pulmonary diseases including asthma. However, VEGF expression in response to nanoparticles is not well understood (McCullagh et al., 2010). Levels of VEGF were significantly reduced in ovalbumin-inhaled female Balb/c mice treated with silver nanoparticles (Jang et al., 2012). (Montiel-Davalos et al., 2012) also concluded that TiO2 nanoparticles (average aggregate size of 50 nm) increased expression levels of VEGF, early and late adhesion molecules (E- and P-selectin, ICAM-1, VCAM-1, PECAM-1), as well as ROS and nitrogen oxide production using an in vitro experimental system. Our findings of increased cytokine expression are consistent with recent studies performed by the authors, evaluating copier emission exposures in both healthy volunteers and in various cell lines. Nasal lavage fluid obtained from human volunteers following a single day exposure to particles emitted from the copiers showed a significant increase (2–10 times) in several inflammatory and immunogenic markers, including VEGF (Khatri et al., 2012). Similarly, in vitro work also revealed overexpression of VEGF and several other cytokines and chemokines in human monocytes and primary upper and small airways cells in response to the same type of particles (Khatri et al., 2013b).

While the exact toxicological pathway for the observed biological responses is unknown, the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is likely to play a central role in lung injury and inflammation, as suggested by recent in vitro studies with toner particles (Gminski et al., 2011, Kleinsorge et al., 2011, Tang et al., 2012a). Likewise, (Khatri et al., 2012) found a notable increase in levels of 8-OH-dG in the urine of humans exposed to photocopier emissions, indicating increased systemic oxidative stress.

Thus far, our results suggest that acute exposure to sampled PM impacted cyto- and chemokine levels as reported in both in vivo and in vitro studies conducted by the authors (Table 3). As shown, levels of IL-1alpha were increased in human nasal and small airway epithelial cells, and in murine bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Moreover, VEGF increased in macrophages, human nasal and small airway epithelial cells, as well as in human nasal and murine lavage fluids. Similar results were observed with other cytokines, including G-CSF. On the other hand, TNF-alpha, IL-6, interferon (IFN)-gamma, among others, were not significantly regulated by exposure to copier-emitted PM after IT exposure but were upregulated in both primary cells from healthy volunteers and in human-derived monocytes. Taken together, the data from this series of studies suggest that the smallest size fraction, PM0.1, of copy center airborne PM is potentially toxic and capable of inducing pulmonary inflammatory responses as shown in various experimental systems.

Table 3.

Comparative summary of toxicological endpoints (inflammatory cells, cytokines/chemokines) measured across different testing platforms (in vitro, in vivo murine and human) in response to nanoparticles emitted from photocopiers.

| Test System | In vitro | In vivo | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Khatri et al., 2013a) | Healthy Volunteers (Khatri et al., 2012) |

Balb/c Mice (This study) |

|||

| Endpoint | THP-1 | Nasal Epithelial Cells |

Small Airway Epithelial Cells |

Nasal lavage | BALF (lungs) |

| ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | |

| CYTOKINES | |||||

| EGF | - | *** | *** | *** | ND |

| Eotaxin | - | - | - | - | * |

| Fractalkine | ** | - | - | *** | ND |

| G-CSF | - | - | - | *** | * |

| GM-CSF | ** | - | * | - | - |

| IFN-γ | - | * | - | - | - |

| IL-1α | - | *** | * | - | * |

| IL-1β | ** | - | * | *** | - |

| IL-3 | ND | ND | ND | ND | * |

| IL-6 | *** | - | - | *** | - |

| IL-8 | *** | *** | *** | *** | ND |

| IP-10 | ND | ND | ND | ND | **** |

| KC | ND | ND | ND | ND | * |

| MCP-1 | *** | - | - | *** | - |

| M-CSF | ND | ND | ND | ND | * |

| MIG | ND | ND | ND | ND | *** |

| TNF-α | *** | * | - | *** | - |

| VEGF | * | ** | ** | *** | *** |

| INFLAMMATORY CELLS | |||||

| Neutrophils | n/a | *** | *** | ||

| Eosinophils | n/a | - | - | ||

| VASCULAR PERMEABILITY | |||||

| Protein / Albumin | ND | ND | ND | *** | *** |

| LDH assay | ND | ND | ND | ND | * |

| OTHER | |||||

| Apoptosis | *** | ND | ND | n/a | ND |

| Necrosis | *** | ND | ND | n/a | ND |

| Genotoxicity | - | ND | ND | *** | ND |

Notes: ↑, Upregulated,

p< 0.0001 (****),

p< 0.001 (***),

p< 0.01 (**),

p< 0.05 (*),

‘-‘, statistically non-significant. The two epithelial cell types are primary human cells. Comparisons are relative to negative controls and restricted for simplicity to the PM0.1 fraction.

THP-1: human monocytes. ND: not determined.

In conclusion, this in vivo investigation validated previous in vitro results indicating the possible toxicological effects of acute inhalation exposures to particles emitted from photocopiers. Future work is needed to further assess the possible effects of chronic exposures to copier-emitted particles and also to study the transient/persistent nature of the observed biological outcomes. Finally, this experimental approach can be used to study other occupational and non-occupational ENP exposures allowing for a more realistic risk assessment and management.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1.Representative morphological images of the toner surface (A, and its EDS), exhaust filter particles (B, and its EDS) and airborne PM (C1, C2, D–H and their EDS. The Cu signal comes from the Cu grid). Reproduced with permission of Informa Healthcare (Bello et al, Nanotoxicology, 2012; 1 (15): 1–15, copyright 2013, Informa Healthcare).

Figure S2. Elemental composition of toners and airborne particulate matter emitted from photocopiers. A1, toner 1; A2, toner 2; B, nanoscale fraction, PM < 0.1; C, fine PM fraction, PM 0.1–2.5; D, coarse PM fraction, PM 2.5–10. Reproduced with permission of Informa Healthcare (Bello et al, Nanotoxicology, 2012; 1 (15): 1–15, copyright 2013, Informa Healthcare)

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding from NIEHS Center Grant ES-000002 and NIOSH and CPSC for the study (Grant # 212-2012-M-51174). Special thanks to Dr. Vincent Castranova (NIOSH) and Dr. Treyes Francis (CPSC) for their support and input.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Anjilvel S, Asgharian B. A multiple-path model of particle deposition in the rat lung. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1995;28:41–50. doi: 10.1006/faat.1995.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonini J, Lawryk N, Murthy G, Brain J. Effect of welding fume solubility on lung macrophage viability and function in vitro. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 1999;58:343–363. doi: 10.1080/009841099157205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonini J, Zeidler-Erdely P, Young S, Roberts J, Erdely A. Systemic immune cell response in rats after pulmonary exposure to manganese-containing particles collected from welding aerosols. J Immunotoxicol. 2012;9:184–192. doi: 10.3109/1547691X.2011.650733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai R, Zhang L, Liu Y, Meng L, Wang L, Wu Y, Li W, Ge C, Le Guyader L, Chen C. Pulmonary responses to printer toner particles in mice after intratracheal instillation. Toxicol Lett. 2010;199:288–300. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan M, Das A. Chromosomal aberration of workers occupationally exposed to photocopy machines in sular, south India. Int J Pharm Bio Sci. 2010;1:B304–B307. [Google Scholar]

- Barthel M, Pedan V, Hahn O, Rothhardt M, Bresch H, Jann O, Seeger S. XRF-analysis of fine and ultrafine particles emitted from laser printing devices. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45:7819–7825. doi: 10.1021/es201590q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck B, Brain J, Bohannon D. An in vivo hamster bioassay to assess the toxicity of particulates for the lungs. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 1982;66:9–29. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(82)90057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bello D, Martin J, Santeufemio C, Sun Q, Lee Bunker K, Shafer M, Demokritou P. Physicochemical and morphological characterisation of nanoparticles from photocopiers: implications for environmental health. Nanotoxicology. 2012 doi: 10.3109/17435390.2012.689883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang P, Bhavsar P, Michaeloudes C, Khorasani N, Chung K. Corticosteroid insensitivity of chemokine expression in airway smooth muscle of patients with severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:877–885. e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K, Patel H, Fadlon E, Rousell J, Haddad E, Jose P, Mitchell J, Belvisi M. Induction of eotaxin expression and release from human airway smooth muscle cells by IL-1β and TNFα: effects of IL-10 and corticosteroids. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1999;127:1145–1150. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Deloid G, Pyrgiotakis G, Demokritou P. Interactions of engineered nanomaterials in physiological media and implications for in vitro dosimetry. Nanotoxicology. 2012 doi: 10.3109/17435390.2012.666576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demokritou P, Buchel R, Molina RM, Deloid GM, Brain JD, Pratsinis SE. Development and characterization of a Versatile Engineered Nanomaterial Generation System (VENGES) suitable for toxicological studies. Inhal Toxicol. 2010;22(Suppl 2):107–116. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2010.499385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demokritou P, Lee SJ, Ferguson ST, Koutrakis P. A compact multistage (cascade) impactor for the characterization of atmospheric' aerosols. Journal of Aerosol Science. 2004;35:281–299. [Google Scholar]

- Dockery D, Arden C, Xu X, Spengler J, Ware J, Fay M, Ferris B, Speizer F. An association between air pollution and mortality in six U.S. cities. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329:1753–1759. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312093292401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominici F, Peng R, Bell M, Pham L, Mcdermott A, Zeger S, Samet J. Fine particulate air pollution and hospital admission for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases. JAMA. 2006;295:1127–1134. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.10.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa Y, Aizawa Y, Okada M, Watanabe M, Niitsuya M, Kotani M. Negative effect of photocopier toner on alveolar macrophages determined by in vitro magnetometric evaluation. Ind Health. 2002;40:214–221. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.40.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gminski R, Decker K, Heinz C, Seidel A, Konczol M, Goldenberg E, Grobety B, Ebner W, Giere R, Mersch-Sundermann V. Genotoxic effects of three selected black toner powders and their dimethyl sulfoxide extracts in cultured human epithelial A549 lung cells in vitro. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2011;52:296–309. doi: 10.1002/em.20621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goud KI, Hasan Q, Balakrishna N, Rao KP, Ahuja YR. Genotoxicity evaluation of individuals working with photocopying machines. Mutation Research-Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis. 2004;563:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson L. Ink and Toner Cartridge Use among SMBs in the United States. Photizo Group. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- Jang S, Park JW, Cha HR, Jung SY, Lee JE, Jung SS, Kim JO, Kim SY, Lee CS, Park HS. Silver nanoparticles modify VEGF signaling pathway and mucus hypersecretion in allergic airway inflammation. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:1329–1343. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S27159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson P, Roth M, Tamm M, Hughes M, Ge Q, King G, Burgess J, Black J. Airway smooth muscle muscle proliferation is increased in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:474–477. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.3.2010109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatri M, Bello D, Gaines P, Martin J, Pal A, Gore R, Woskie S. Nanoparticles from photocopiers induce oxidative stress and upper respiratory tract inflammation in healthy volunteers. Nanotoxicology. 2012 doi: 10.3109/17435390.2012.691998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatri M, Bello D, Pal A, Woskie S, Gassert T, Cohen J, Pyrgiotakis G, Demokritou P, Gaines P. Human cell line evaluation of cytotoxic, genotoxic and inflammatory responses caused by nanoparticles from photocopiers. Particle and Fiber Toxicology. 2013a doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-10-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatri M, Bello D, Pal A, Woskie S, Gassert T, Demokritou P, Gaines P. Toxicological effects of PM0.1–2.5 particles collected from a photocopy center in three human cell lines. Inhalation Toxicology. 2013b doi: 10.3109/08958378.2013.824525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinsorge E, Erben M, Galan M, Barison C, Gonsebatt M, Simoniello M. Assessment of oxidative status and genotoxicity in photocopier operators: a pilot study. Biomarkers. 2011;16:642–648. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2011.620744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konczol M, Weiss A, Gminski R, Merfort I, Mersch-Sundermann V. Oxidative stress and inflammatory response to printer toner particles in human epithelial A549 lung cells. Toxicol Lett. 2013;216:171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2012.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Hsu D. Measurements of fine and ultrafine particles formation in photocopy centers in Taiwan. Atmospheric Environment. 2007;41:6598–6609. [Google Scholar]

- Lin G. Toxicological studies of a representative Xerox reprographic toner. International Journal of Toxicology. 1994;18:23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lough G, Schauer J, Park J, Shafer M, Deminter J, Weinstein J. Emissions of metals associated with motor vehicle roadways. Environ Sci Technol. 2005;39:826–836. doi: 10.1021/es048715f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manikantan P, Balachandar V, Sasikala K, Mohanadevi S, Lakshmankumar B. DNA Damage in workers occupationally exposed to photocopying machines in Coimbatore south India, using comet assay. The Internet Journal of Toxicology. 2010;7 [Google Scholar]

- Mccullagh A, Rosenthal M, Wanner A, Hurtado A, Padley S, Bush A. The bronchial circulation--worth a closer look: a review of the relationship between the bronchial vasculature and airway inflammation. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2010;45:1–13. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr U, Ernst H, Roller M, Pott F. Carcinogenicity study with nineteen granular dusts in rats. Eur J Oncol. 2005;10:249–281. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr U, Ernst H, Roller M, Pott F. Pulmonary tumor types induced in Wistar rats of the so-called "19-dust study". Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2006;58:13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller A, Muhle H, Creutzenberg O, Bruch J, Rehn B, Blome H. Biological procedures for the toxicological assessment of toner dusts. Gefahrstoffe—Reinhaltung der Luft. 2004;64:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Montiel-Davalos A, Ventura-Gallegos JL, Alfaro-Moreno E, Soria-Castro E, Garcia-Latorre E, Cabanas-Moreno JG, Del Pilar Ramos-Godinez M, Lopez-Marure R. TiO(2) nanoparticles induce dysfunction and activation of human endothelial cells. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25:920–930. doi: 10.1021/tx200551u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morawska L, He C, Johnson G, Jayaratne R, Salthammer T, Wang H, Uhde E, Bostrom T, Modini R, Ayoko G, Mcgarry P, Wensing M. An Investigation into the Characteristics and Formation Mechanisms of Particles Originating from the Operation of Laser Printers. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43:1015–1022. doi: 10.1021/es802193n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto Y, Kim H, Oyabu T, Hirohashi M, Nagatomo H, Ogami A, Yamato H, Obata Y, Kasai H, Higashi T, Tanaka I. Negative effect of long-term inhalation of toner on formation of 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine in DNA in the lungs of rats in vivo. Inhalation Toxicology. 2005;17:749–753. doi: 10.1080/08958370500224771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto Y, Ogami A, Todoroki M, Yamamoto M, Murakami M, Hirohashi M, Oyabu T, Myojo T, Nishi K, Kadoya C, Yamasaki S, Nagatomo H, Fujita K, Endoh S, Uchida K, Yamamoto K, Kobayashi N, Nakanishi J, Tanaka I. Expression of inflammation-related cytokines following intratracheal instillation of nickel oxide nanoparticles. Nanotoxicology. 2010;4:161–176. doi: 10.3109/17435390903518479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel D, Tamakuwala D, Solanki K, Pithawala M, Gadhia P. A preliminary cytogenetic and hematological study of photocopying machine operators. Indian Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine. 2005;9:22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Perrone MG, Gualtieri M, Consonni V, Ferrero L, Sangiorgi G, Longhin E, Ballabio D, Bolzacchini E, Camatini M. Particle size, chemical composition, seasons of the year and urban, rural or remote site origins as determinants of biological effects of particulate matter on pulmonary cells. Environ Pollut. 2013;176C:215–227. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehn B, Bruch J, Zou T, Hobusch G. Recovery of rat alveolar macrophages by bronchoalveolar lavage under normal and activated conditions. Environ Health Perspect. 1992;97:11–16. doi: 10.1289/ehp.929711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slesinski RS, Turnbull D. Chronic inhalation exposure of rats for up to 104 weeks to a non-carbon-based magnetite photocopying toner. Int J Toxicol. 2008;27:427–439. doi: 10.1080/10915810802616560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sotiriou GA, Diaz E, Long MS, Godleski J, Brain J, Pratsinis SE, Demokritou P. A novel platform for pulmonary and cardiovascular toxicological characterization of inhaled engineered nanomaterials. Nanotoxicology. 2012;6:680–690. doi: 10.3109/17435390.2011.604439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriram K, Lin GX, Jefferson AM, Roberts JR, Andrews RN, Kashon ML, Antonini JM. Manganese accumulation in nail clippings as a biomarker of welding fume exposure and neurotoxicity. Toxicology. 2012;291:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart C. Copying success. The Orange County Register. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Tang T, Gminski R, Konczol M, Modest C, Armbruster B, Mersch-Sundermann V. Investigations on cytotoxic and genotoxic effects of laser printer emissions in human epithelial A549 lung cells using an air/liquid exposure system. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2012a;53:125–135. doi: 10.1002/em.20695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang T, Hurrass J, Gminski R, Mersch-Sundermann V. Fine and ultrafine particles emitted from laser printers as indoor air contaminants in German offices. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2012b;19:3840–3849. doi: 10.1007/s11356-011-0647-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taurozzi JS, Hackley VA, Wiesner MR. Ultrasonic dispersion of nanoparticles for environmental, health and safety assessment - issues and recommendations. Nanotoxicology. 2010 doi: 10.3109/17435390.2010.528846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wensing M, Pinz G, Bednarek M, Schripp T, Uhde E, Salthammer T. Healthy Buildings Conference. Lisboa: 2006. Particle measurement of hardcopy devices. [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Haung Y. A cross-sectional study of respiratory and irritant health symptoms in photocopier workers in Taiwan. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2008;71:1314–1317. doi: 10.1080/15287390802240785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yazdi AS, Guarda G, Riteau N, Drexler SK, Tardivel A, Couillin I, Tschopp J. Nanoparticles activate the NLR pyrin domain containing 3 (Nlrp3) inflammasome and cause pulmonary inflammation through release of IL-1alpha and IL-1beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:19449–19454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008155107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidler-Erdely P, Battelli L, Salmen-Muniz R, Li Z, Erdely A, Kashon M, Simeonova P, Antonini J. Lung tumor production and tissue metal distribution after exposure to manual metal ARC-stainless steel welding fume in A/J and C57BL/6J mice. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2011;74:728–736. doi: 10.1080/15287394.2011.556063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Gao Z, Tian Z, Xie Y, Xin F, Jiang R, Kan H, Song W. The biological effects of individual-level PM2.5 exposure on systemic immunity and inflammatory response in traffic policemen. Occup Environ Med. 2013 doi: 10.1136/oemed-2012-100864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1.Representative morphological images of the toner surface (A, and its EDS), exhaust filter particles (B, and its EDS) and airborne PM (C1, C2, D–H and their EDS. The Cu signal comes from the Cu grid). Reproduced with permission of Informa Healthcare (Bello et al, Nanotoxicology, 2012; 1 (15): 1–15, copyright 2013, Informa Healthcare).

Figure S2. Elemental composition of toners and airborne particulate matter emitted from photocopiers. A1, toner 1; A2, toner 2; B, nanoscale fraction, PM < 0.1; C, fine PM fraction, PM 0.1–2.5; D, coarse PM fraction, PM 2.5–10. Reproduced with permission of Informa Healthcare (Bello et al, Nanotoxicology, 2012; 1 (15): 1–15, copyright 2013, Informa Healthcare)