INTRODUCTION

Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine; 5-HT) was discovered in the lining of the gastrointestinal tract in 1935; a detailed history on its discovery and characterization was published several years later.1 5-HT is a derivative of the amino acid L-tryptophan, which is synthesized by tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH) with its two isoforms. TPH1 is responsible for the production of 5-HT in peripheral tissues2 and TPH2 leads to the synthesis of 5-HT in the central nervous system.3 5-HT is metabolized in liver and eventually excreted as 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid. Platelets are likely the biological storage of circulating 5-HT. Platelets do not synthesize 5-HT but acquire it, mainly from the blood, after being secreted by the enterochromaffin cells of the intestine. The free 5-HT level in the blood is tightly regulated by a specific transporter, SERT (SLC6A4), which is expressed on the platelet surface.4 SERT removes 5-HT from the blood via a saturable reuptake mechanism.4 Once in the cytoplasm, 5-HT is sequestered by the vesicular monoamine transporter type 2 into intracellular dense granules. 4–6 5-HT concentration in resting platelets is millimolar versus in the blood where it is in the low nanomolar range. 5, 6 Although, 5-HT is better known as a neurotransmitter with key roles in a variety of psychiatric diseases, it also has extra-cerebral roles: multifunctional signaling molecule, growth factor, endocrine hormone or paracrine messenger, from fetal to adult life.2, 7, 8

5-HT in platelet aggregation

Platelets are derived from the fragmented cytoplasm of megakaryocytes and enter the circulation in an inactive form. The initial activation of platelets stabilizes them in hemostasis. Further platelet activation enlists more platelets at a fibrin-stabilized hemostatic area to form a thrombus after associating with the endothelium or each other. The role of circulating, free 5-HT in platelet adhesion, aggregation, and thrombus formation has not been resolved completely, but clinical and biochemical findings infer a complex process. An elevation in free 5-HT levels in plasma accelerates the exocytosis of dense and α-granules9, 10; in turn, these secrete 5-HT and other procoagulant molecules that will mediate hemostasis. Supporting these hypotheses is the fact that platelets of 5-HT infused mice, in the absence of cardiovascular problem, show an enhanced aggregation profile; however, when the 5-HT-infused mice were injected with a selective 5-HT reuptake inhibitor (SSRI)11, 12 or a 5-HT2A antagonist11, 13 the effect of elevated free 5-HT levels in plasma was reversed and the platelet aggregation profile normalized.11–14 The importance of the plasma 5-HT level and platelet SERT in the platelet aggregation phenomenon is supported by findings in platelets of mice lacking the gene for TPH111, 14 or the gene for SERT:11 where granular secretion rates as well as the risk of thrombosis are significantly reduced.11, 12, 14 Following the interaction with von Willebrand factor and 5-HT2A receptors, 5-HT-mediated platelet aggregation occurs via 5-HT2A- or SERT-dependent pathways. 11, 12, 15–18

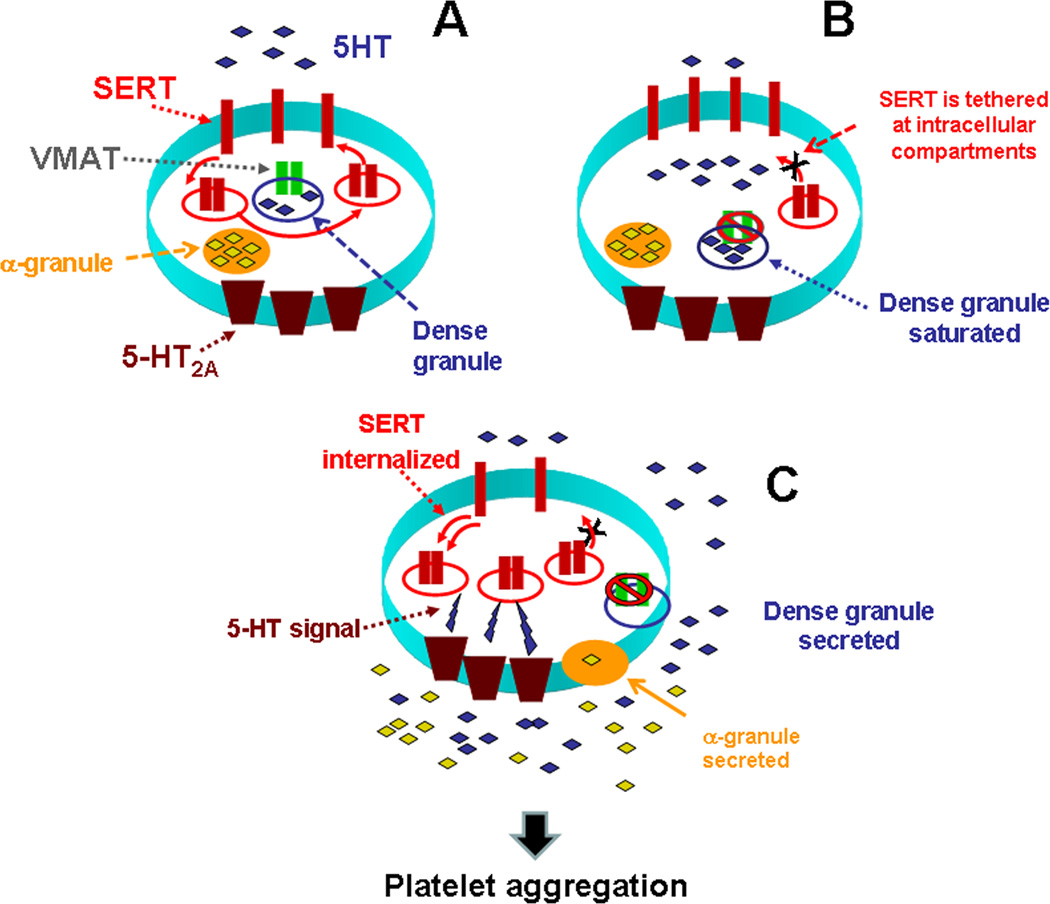

In a receptor–dependent pathway, 5-HT11, 13, 19 initiates G-protein-dependent signaling pathway to mobilize calcium from intracellular stores.6, 9, 15, 20–28 Free, calcium activates transglutaminase (TGase) which transamidates cytoplasmic 5-HT to the GTP-GDP hydrolysis domains of the small GTPases.28 In the active, GTP-bound form, small GTPases promotes the exocytosis of the granule.12, 14, 28, 29 At this point the contribution of intracellular 5-HT to the SERT–dependent platelet aggregation pathway appears important. Once the free/unbound 5-HT is taken up by SERT in platelet cytosol, it is stored in dense granules. However, upon the saturation of dense granules, free/unbound 5-HT in the platelet cytosol is transamidated on the GTP-GDP hydrolysis domain of the small GTPases converting them to their active GTP-bound form, to enhance α-granule secretion.9, 11, 12, 14 Concurrently, the association between Rab4-GTP and SERT tethers the transporter to an intracellular compartment to prevent further rises in cytoplasmic 5-HT.12, 28, 29 Additionally, elevated plasma 5-HT activates p21 activating kinase (PAK) which phosphorylates the intermediate filament vimentin.30, 31 We reported that under physiological conditions SERT binds to vimentin during internalization from the plasma membrane.32 However, following the phosphorylation of vimentin, the level of SERT on phosphovimentin as well as the internalization rate of SERT from the plasma membrane to intracellular compartments are elevated.32 Based on these findings we propose that plasma 5-HT at high levels leads to abnormalities in the platelet trafficking of SERT, which reduces the density of SERT molecules on the plasma membrane. These events are correlated with the platelet aggregation process. Mechanistically, these finding investigate the link between elevated plasma 5-HT and loss of surface SERT by focusing on the intracellular tethering of SERT by Rab428 and the 5-HT-mediated phosphorylation of vimentin that promotes SERT internalization32 in platelets (Fig. 1). In supporting our findings on the importance of SERT and SSRI in platelet aggregation process, studies with a different approach, showed that stimulation of 5-HT2A decreases the adhesive property of platelet by shedding of GPIb from the platelet surface.33 However, platelet SERT clears 5-HT from plasma which becomes no longer available to stimulate 5-HT2A stimulation, in the presence of SSRI platelet loses adhesive properties.33

Figure 1.

(A) High 5-HT leads to abnormalities in the platelet trafficking of SERT, which reduces the density of SERT molecules on the plasma membrane. (B) Based on our findings for the known actions of 5-HT in platelets, we propose that high levels of uptake leads to saturation of dense granules and 5-HT appears in the platelet cytoplasm. VMAT is disabled and cannot remove 5-HT in dense granules anymore. This leads to the serotonylation of small GTPases such as Rab4, Rho and Rac via Ca2+-activated TGase. In GTP form, Rab4 binds and prevents the translocation of SERT to the plasma membrane. (C) These processes are involved in platelet activation and aggregation in a two-step process: in the first step elevated 5-HT controls the platelet 5-HT uptake rates via altering the membrane trafficking of plasma membrane SERT which in turn elevates the plasma 5-HT level further; then in the second step the elevated plasma 5-HT level activates 5-HT2A which accelerates the exocytosis of α-granules. Secretion of prothrombotic molecules from α-granules to the plasma with high levels of 5-HT propagates the thrombus formation. However, even at the highest levels of plasma 5-HT, there are always a number of SERT molecules on the plasma membrane that still continue to clear plasma 5-HT, but with a lower rate, most probably until the plasma 5-HT level returns to the physiological level.

In a recent study, we reported that at elevated level plasma 5-HT was associated with a change in the density and/or composition of N-glycans on the platelet surface and this abnormality was allied with an enhanced rate of platelet aggregation.11 Earlier studies with the platelets of fawn-hooded rats showed a connection between plasma 5-HT level and platelet functions.34–37 The genetic disorder in the platelet function of fawn-hooded rat appears similar to the storage pool disease. The reduced level of ATP, ADP and 5-HT in the platelets and the glycoprotein structure on the surface of platelets of fawn-hooded rates reduce their aggregation rates and contribute to the platelet disorder.34–37

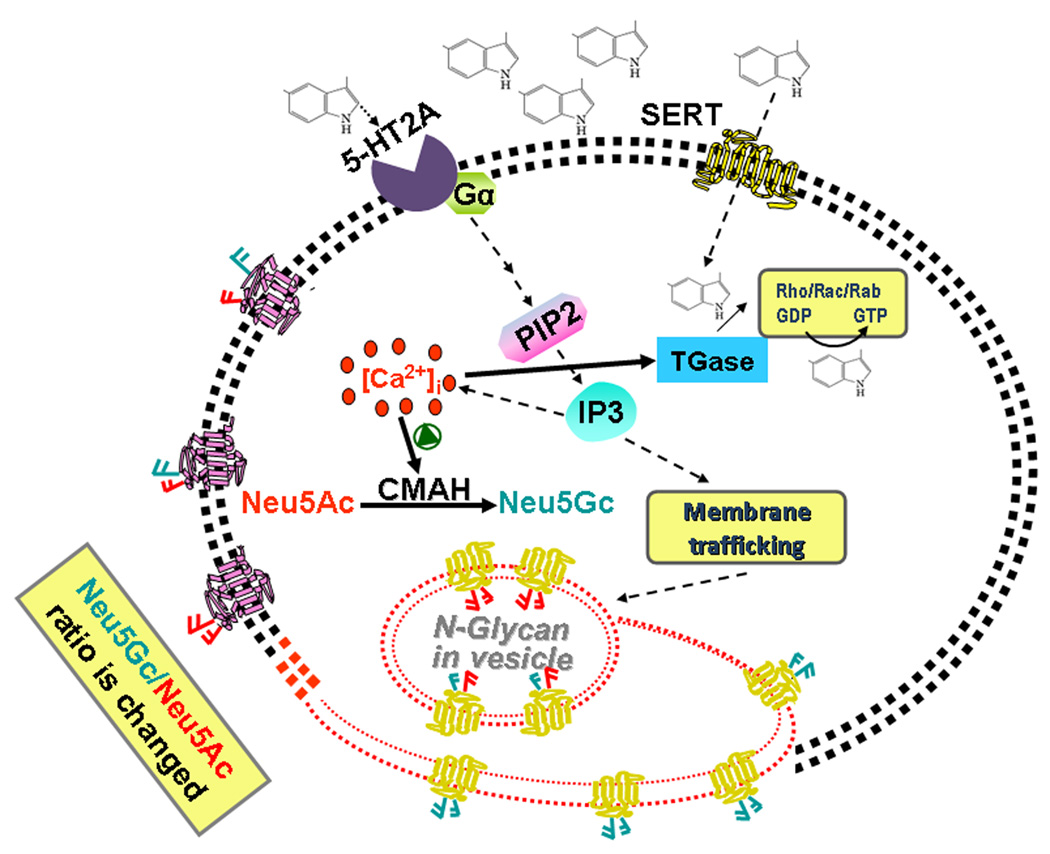

5-HT infusion in mice elevates plasma 5-HT levels and alters the terminal N-glycan content of platelet surface proteins; this enhances platelet aggregation, establishing the surface glycan as a key mediator in platelet activation. Others reported that sialic acid at the terminal position of N-glycans promoted the cell-cell adhesion by acting as a ligand for receptors such as P- and E-selectins.38 Therefore this feature of sialic acids could also be expected for the aggregation characteristics of platelets. However, before our studies, neither the involvement of 5-HT in N-glycan switching nor the role of N-glycans on platelet aggregation was reported.11 Comparing the 5-HT infused TPH1-KO and SERT-KO mice models with wild type counterparts, we found that the plasma membrane of platelets isolated from 5-HT-infused mice had predominantly N-glycolyl-neuraminic acid (Neu5Gc) containing N-glycans.11 Plasma 5-HT at a high level elevates the Neu5Gc level on the platelet surface, not only promoting its biosynthesis through the catalytic activity of CMP-N-acetyl-neuraminic acid hydroxylase (CMAH) but also promoting the translocation rates of the vesicles carrying Neu5Gc containing N-glycans to the plasma membrane (Fig. 2). 5-HT-infused SERT KO mice (deficient in intracellular 5-HT) showed nearly 2-fold higher CMAH activity than the control mice. Since Neu5Gc is formed from Neu5Ac via the catalytic action of CMAH, the predominance of Neu5Gc on platelets of 5-HT infused mice suggests that 5-HT signaling enhances the catalytic function of CMAH in a 5-HT2A receptor –dependent pathway and elevates the density of Neu5Gc on the platelet surface.11 These findings concurred with FACS analysis of platelets stained with Neu5Gc antibodies.

Figure 2.

The stimulation of cells with 5-HT activates, via 5-HT2A signaling, the production of Neu5Gc via the catalytic function of CMAH. 5-HT signaling is mediated by the G protein-coupled 5-HT2A which facilitates the formation of Inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) resulting in a rise of cytoplasmic Ca2+ in platelets. Based on our reported and unpublished data, we propose that elevated intracellular Ca2+ activates CMAH, which elevates the number of Neu5Gc containing N-glycans on the plasma membrane of platelets. Our studies showed that 5-HT signaling is important either on trafficking of Neu5Gc (presented in the diagram in blue) containing vesicles to the plasma membrane or enhancing the catalytic ability of CMAH or both in inducing platelet activation and aggregation.

In summary, the involvement of 5-HT in platelet aggregation mechanism appears to be through multiple pathways.

5-HT in hypertension-associated platelet aggregation

The plasma 5-HT level is elevated in various conditions, including hypertension39–43 and thrombosis.6, 9–11, 12, 42 However, in the absence of cardiovascular disease, in vivo administration of 5-HT does not increase systolic blood pressure12 suggesting that the elevation in plasma 5-HT level could be a consequence rather than a cause of some forms of hypertension. The action of plasma 5-HT on blood pressure can be varied with its acute or chronic elevation and the location in the circulation system. For example, the blood pressure of deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)-salt hypertensive rats was decreased over the course of one month of 5-HT infusion.43 If the prothrombotic action of elevated 5-HT level in plasma were ignored, its blood pressure lowering capacity would be a novel approach to the hypertension studies.

Hypertension is characterized by an increased vascular resistance that can be caused by vasoconstriction.44 Several studies report an elevation in plasma 5-HT concentration in hypertensive subjects that concurrently have diabetes and coronary artery disease8, 20, 21, 39, 40, 42, 43 as well as in a variety of other cardiovascular pathologies including cerebrovascular disease and arterial thrombosis.6, 11–14 Since these conditions share platelet activation as a disease mechanism, attention has focused on identifying the complex mechanisms by which 5-HT may promote platelet activation. The cause of elevated 5-HT could be due to an increase in the exocytosis rates of dense granules and/or 5-HT secretion from the enterochromaffin cells of the intestine. 5-HT is also a well-known arterial vasoconstrictor, as described by Rapport, as early as 1945.44

In many forms of experimental and human hypertension2, 8, 16, 39–43 plasma 5-HT levels are reported as elevated but thrombosis is not commonly encountered in hypertension. Biochemical and functional analyses of lungs, platelets, and pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells showed a direct involvement of the SERT/RhoA/Rho kinase signaling pathway in 5-HT–mediated platelet activation during pulmonary hypertension.45

When the plasma 5-HT level, systolic blood pressure (SBP) and the rate of platelet aggregation are compared in two preclinical models of hypertension (angiotensin II-infused for 7 days or cocaine-injected for 30 min),16, 46 the blood plasma 5-HT levels as well as the SBP are found as elevated in both hypertensive models, but only cocaine and not Ang II, exerted a pro-thrombotic effect.16, 46

The platelets in hypertensive subjects have an abnormal biological profile compared to platelets of normal subjects.47 The abnormal endothelium in hypertension promotes platelet activation, aggregation, and thrombosis and these maintain further elevation of SBP. Whether different mechanisms of hypertension differentially predispose platelets to thrombosis is not clear yet. To address this issue, the effect of elevated plasma 5-HT on platelets was compared in angiotensin II-infused mice (mimics the activated renin-angiotensin system)16 with cocaine-injected (sympathetic nervous system is activated) mice.46

Cocaine-induced mouse model of hypertension

Cocaine is a powerful sympathomimetic agent that causes acute elevations in arterial pressures; the net effect of cocaine on SBP and diastolic blood pressures in humans is an increase of 20 mm Hg and 10 mm Hg respectively.48–50 In peripheral tissues, cocaine produces a sympathomimetic response by inhibiting the reuptake of 5-HT and catecholamines leading to a transient bradycardia followed by tachycardia, hypertension, and acute thrombosis in coronary arteries.24, 51–53 Studies agree that cocaine-related cardiovascular effects do not require preexisting vascular disease.51

Through a variety of mechanisms, cocaine increases the risk of thrombosis.51 Even in the absence of systemic platelet activation, endothelial dysfunction, or cardiovascular complications, cocaine is associated with acute thrombosis of coronary arteries.51–55 Autopsy studies have demonstrated the presence of coronary atherosclerosis in young cocaine users along with associated thrombus formation;52 thus, cocaine use is associated with premature coronary atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Platelets isolated from cocaine-injected mice appear hyper-reactive and form thrombi as a result of elevated exocytosis of α-granules and of plasminogen-activator inhibitor level but a decreased antithrombin-III level.51, 53, 55

The role of 5-HT in cocaine-mediated thrombus formation is poorly understood. Cocaine acts as a ligand on SERT and reduces the 5-HT reuptake rates of the cells. However, when mice were injected with cocaine, their plasma 5-HT was elevated to the level found in SSRI-injected mice;12, 46 however, contrary to the effects of SSRI, platelets became hyper-reactive.54 Platelets of cocaine-injected TPH1-KO mice compared with platelets isolated from TPH1-KO mice had higher aggregation rates by 10%; surprisingly, in cocaine-injected DAT-KI mice (Cocaine-insensitive dopamine transporter-knocked) platelets were already prothrombotic with aggregation rates 20% higher than the rates observed in the control group.46 DAT-KI mice are introduced genetically with cocaine-insensitive DAT which made them 70-fold less sensitive to cocaine but fully functional for dopamine uptake.56 Our findings suggest participation of the sympathetic nervous system in cocaine-mediated platelet aggregation via the synergistic actions of 5-HT and nonserotonergic amines such as catecholamines.46

Ang II-induced mouse model of hypertension

Ang II, part of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system contributes to hypertension.57 Whether Ang II-mediated hypertension is associated with a prothrombotic state remains controversial. Whereas some studies report a prothrombotic effect of Ang II57–59, others report a protective effect of Ang II that is independent of its pressor effects60–62 and may rely on elevated prostacyclin or nitric oxide to inhibit platelet aggregation.62, 63 Thus, we studied the correlation between elevated serum Ang II and the adhesive properties of platelets.16 The hypertensive model was established on adult C57BL/6J male mice infused isotonic saline or Ang II via osmotic mini-pumps.16 Baseline SBP was measured on 6 consecutive days prior to insertion of the mini-pumps. Then, SBP in each mouse was averaged from ≥6 trials each day for one week after saline- or Ang- II infusion. Ang II infused for one week increased SBP from 101±8.6 mm Hg to 180±12 mm Hg (average increase of 78%).

5-HT and platelet aggregation in Ang II and cocaine models

After confirmation of a SBP increase following cocaine-injection or Ang II-infusion, plasma 5-HT concentration in saline, Ang- infused, and cocaine-injected mice was determined.16, 46 Neither 30 min cocaine-injection nor 7 days Ang II infusion caused a change in circulating platelet counts (not shown). However, accentuated collagen-induced aggregation was observed in platelets from cocaine-injected mice; this was on average 50% higher compared to that observed in platelets from saline- or Ang II-infused mice.16, 46 These findings were confirmed by showing a significant elevation in P-selectin (marker of platelet activation) by flow cytometry. Thus, exposure to cocaine coincides with a heightened platelet response to collagen and enhanced platelet activation (Table 1). The 5-HT level was 2.8-fold higher in cocaine-injected mice than Ang II-infused mice but in both groups, Ang II and cocaine, the levels of SBP and 5-HT levels were elevated. Hypertension was associated with one week Ang II-infusion or 30 min cocaine-injection, plasma 5-HT levels were relatively elevated, but only the platelets of cocaine-injected mice were hyperreactive.

TABLE 1.

The summary of our findings in 4 groups of mice model system

| Mice-Infused | Saline | 5-HT | Ang II | Cocaine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SBP (mm Hg) | 101 ± 8.6 | 106 ± 14 | 180 ± 19 | 146 ± 15 |

| [5-HT] in plasma (ng/ml blood) | 0.85 ± 0.04 | 2.74 ± 0.37 | 1.24 ± 0.27 | 3.50 ± 0.18 |

| Platelet aggregation | 35.8 ± 12 | 70.7 ± 7.63 | 32 ± 2.06 | 64.33 ± 4.04 |

| FACS analysis of P-selectin | 181.7 ± 8.00 | 316.05 ± 2.61 | 145 ± 7.35 | 325 ± 11.2 |

Adult C57BL/6J male mice which were inserted osmotic pumps filled with 5-HT (0.05 mg/ml, with an infusion rate of 1.66 µg/kg/hr)12 or Ang II (24 µg Ang II/gram body weight with infusion rate of 2 ng/g/min)16 for 24 hrs or 7 days, respectively. Also, a set of C57BL/6J mice were injected with cocaine at 30 mg/kg for 30 min.46 The baseline SBP was measured on 6 consecutive days prior to insertion of mini-pumps. All assays were performed in triplicate. mean ± SEM; n=15 for all groups.

The known effects of drugs interacting with SERT activity on platelet function in the setting of systemic hypertension

Plasma 5-HT levels are elevated in a variety of pathologies including hypertension, thrombotic disease and carcinoid syndrome. The direct contribution of 5-HT to thrombosis is difficult to assess in complex diseases such as hypertension. However, in carcinoid syndrome, carcinoid tumors overproduce 5-HT and the increased circulating level of 5-HT (and other hormones) is correlated with the formation of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Although the evidence linking 5-HT to hypercoagulable states is mainly correlative, Sarpogrelate-ANPLAG® is marketed in Japan, China and Korea as an anti-platelet agent.64–66

These implicate that 5-HT in human diseases associated with abnormal coagulation. One of the best examples in connecting 5-HT and hypertension is “serotonin syndrome” which generally occurs if the physiological 5-HT level is elevated by using two of the following drugs at the same time, triptans, SSRI, selective serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake, ecstasy, LSD, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, meperidine, dextromethorphan. The combination of these drugs causes the elevation of 5-HT level significantly higher than the physiological level which creates a prethrombotic environment for platelet. Despite the availability of a wide range of effective BP-lowering agents, a substantial proportion of patients with hypertension fail to achieve target BP levels. The majority of patients with hypertension need at least two drugs to achieve BP control so it is important to identify new medication targets.

The cardiovascular effects of 5-HT are not uniform: bradycardia or tachycardia, hypotension or hypertension, vasodilatation or vasoconstriction. These responses are mediated by 5-HT1, 5-HT2, 5-HT3, 5-HT4, 5-HT5A/5B, and 5-HT7 receptors as well as by a tyramine-like action in the central nervous system, autonomic ganglia, postganglionic nerve endings, vascular smooth muscle, endothelium and cardiac tissue. For example, BP response to administration of 5-HT is triphasic: initial short-lasting vasodepressor phase (reflex bradycardia due to 5-HT3 receptors on vagal afferents), a middle vasopressor phase (5-HT2A receptors) and a late, longer-lasting, vasodepressor phase (direct vasorelaxation by activation of 5-HT7 receptors located on vascular smooth muscle, inhibition of the vasopressor sympathetic outflow by sympatho-inhibitory 5-HT1A/1B/1D receptors and release of endothelial nitric oxide by 5-HT2B and/or 5-HT1B/1D receptors). Furthermore, central administration of 5-HT can cause both hypotension (5-HT1A receptors) and hypertension (5-HT2 receptors).

Because of this complexity, until now, only 2 drugs have been found to have blood pressure lowering effect. Both work on alpha1-adrenoceptors as well as 5-HT receptors. Ketanserin affects baroreflex function by blocking 5-HT2A receptors and/or alpha1-adrenoceptors through central and/or peripheral mechanisms.66, 67 On the other side, Urapidil has an alpha-blocking effect and also a central sympatholytic effect mediated via stimulation of 5HT1A receptors in the central nervous system.68, 69

Further studies on the role of 5-HT in hypertension, new compounds with high affinity and selectivity for the different 5-HT receptor subtypes together with SERT may be used as a therapy in the hypertension armamentarium.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

5-HT in peripheral tissues as well as the central nervous system has a rich history in pharmacology and this has translated into a widely exploited therapeutic target. New insights into the regulation of SERT and 5-HT2A functions in platelet biology may open new dimensions in the targeting of the additive effect of plasma 5-HT on platelet aggregation. We have focused here on the known mechanisms in which 5-HT impacts platelet biology in cardiovascular diseases.

Elevations of plasma 5-HT levels have been reported in a variety of cardiovascular pathologies including hypertension, atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease, angina, and arterial thrombosis.6, 14, 11, 12, 13, 39, 40 Since these conditions share platelet activation as a disease component, attention has focused on identifying the complex mechanisms by which 5-HT may promote platelet activation.

Considering the role of 5-HT in platelet aggregation, a loss of platelet SERT coupled with elevated plasma 5-HT may play a significant role in cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, atherosclerosis, and peripheral arterial disease; this is thought to reflect a common prothrombotic state. Numerous factors have been identified that confer this increased susceptibility to thrombosis, including a loss of endothelial-derived nitric oxide, vascular smooth muscle cell hypertrophy, hyperinsulinemia, and other metabolic abnormalities, obesity, and inflammation.1, 37, 20, 21 The development of possible antithrombotic therapies for patients with cardiovascular disease has focused on reducing these risk factors rather than on targeting endogenous mechanisms responsible for the prothrombosic state. In this regard, therapies designed to promote the expression of SERT on the platelet surface and thereby reduce plasma levels of 5-HT may represent a novel approach to alleviating thrombotic events as well as controlling blood pressure.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank her collaborators, colleagues, and the students who have contributed across disciplines to the understanding of platelet function.

DAT-KI mice were obtained from Dr. Howard Gu as a generous gift; he generated these mice and used them in several studies successfully.53

SOURCE OF FUNDING:

This work was supported by the IDeA program-P30 GM110702 from National Institutes of Health-NIGMS; American Heart Association [GRNT17240014] and by the National Institutes of Health, NHLBI [R01HL091196 and R01HL091196-01A2W1] to FK.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE:

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gershon MD, Tack J. The serotonin signaling system: from basic understanding to drug development for functional GI disorders. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:397–414. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Côté F, Thévenot E, Fligny C, Fromes Y, Darmon M, Ripoche MA, Bayard E, Hanoun N, Saurini F, Lechat P, Dandolo L, Hamon M, Mallet J, Vodjdani G. Disruption of the nonneuronal tph1 gene demonstrates the importance of peripheral serotonin in cardiac function. Proc Natl Acad Sci. USA. 2003;100:13525–13530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2233056100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walther DJ, Peter JU, Bashammakh S, Hortnagl H, Voits M, Fink H, Bader M. Synthesis of serotonin by a second tryptophan hydroxylase isoform. Science. 2003;299:76. doi: 10.1126/science.1078197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Talvenheimo J, Nelson PJ, Rudnick G. Mechanism of imipramine inhibition of platelet 5-hydroxytryptamine transport. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:4631–4635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holmsen H, Weiss HJ. Secretable storage pools in platelets. Annu Rev Med. 1979;30:119–134. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.30.020179.001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McNicol A, Israels SJ. Platelet Dense Granules: Structure, Function and Implications for. Haemostasis Throm Res. 1999;95:1–18. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(99)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lauder JM, Tamir H, Sadler TW. Serotonin and morphogenesis. I. Sites of serotonin uptake and binding protein immunoreactivity in the midgestation mouse embryo. Development. 1998;102:709–720. doi: 10.1242/dev.102.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Côté F, Fligny C, Bayard E, Launay JM, Gershon MD, Mallet J, Vodjdani G. Maternal serotonin is crucial for murine embryonic development. Proc Natl Acad Sci. USA. 2007;104:329–334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606722104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shirakawa R, Yoshioka A, Horiuchi H, Nishioka H, Tabuchi A, Kita T. Small GTPase Rab4 regulates Ca2+-induced α-granule secretion in platelets. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33844–33849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002834200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crosby D, Poole AW. Platelet dense-granule secretion: the (3H)-5-HT secretion assay Methods. Mol Biol. 2004;272:95–96. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-782-3:095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mercado CP, Quintero MV, Li Y, Singh P, Byrd AK, Talabnin K, Ishihara M, Azadi P, Rusch NJ, Kuberan B, Maroteaux L, Kilic F. A serotonin-induced N-glycan switch regulates platelet aggregation. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2795. doi: 10.1038/srep02795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ziu E, Freyaldenhoven S, Mercado CP, Ahmed BA, Preeti P, Lensing S, Ware J, Kilic F. Down-regulation of the Serotonin Transporter in hyper-reactive platelets counteracts the pro-thrombotic effect of serotonin. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:1112–11121. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Przyklenk K. Targeted inhibition of the serotonin 5HT2A receptor improves coronary patency in an in vivo model of recurrent thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:331–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03693.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walther DJ, Peter JU, Winter S, Holtje M, Paulmann N, Grohmann M, Vowinckel J, Alamo-Bethencourt V, Wilhelm CS, Ahnert-Hilger G, Bader M. Serotonylation of small GTPases is a signal transduction pathway that triggers platelet alpha-granule release. Cell. 2003;115:851–862. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mercado C, Kilic F. Molecular mechanisms of SERT in platelets: regulation of plasma serotonin levels. Molecular Interventions. 2010;10:231–241. doi: 10.1124/mi.10.4.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh P, Fletcher TW, Li Y, Rusch NJ, Kilic F. Serotonin uptake rates in platelets from angiotension II-induced hypertensive mice. Health, Special issue on Hypertension and Cardiovascular Diseases. 2013;5:31–39. doi: 10.4236/health.2013.54A005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Léon C, Hechler B, Freund M, Eckly A, Vial C, Ohlmann P, Dierich A, LeMeur M, Cazenave JP, Gachet C. Defective platelet aggregation and increased resistance to thrombosis in purinergic P2Y(1) receptor-null mice. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1731–1737. doi: 10.1172/JCI8399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brass LF. More pieces of the platelet activation puzzle slide into place. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:1663–1665. doi: 10.1172/JCI8944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishihira K, Yamashita A, Tanaka N, Kawamoto R, Imamura T, Yamamoto R, Eto T, Asada Y. Inhibition of 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor prevents occlusive thrombus formation on neointima of the rabbit femoral artery. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:247–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van den Berg EK, Schmitz JM, Benedict CR, Malloy CR, Willerson JT, Dehmer GJ. Transcardiac serotonin concentration is increased in selected patients with limiting angina and complex coronary lesion morphology. Circulation. 1989;79:116–124. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.1.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pietraszek MH, Takada Y, Takada A, Fujita M, Watanabe I, Taminato A, Yoshimi T. Blood serotonergic mechanisms in type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Thromb Res. 1992;66:765–774. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(92)90052-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saxena PR, Villalon CM. Cardiovascular effects of serotonin agonists and antagonists. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1990;7:S17–S34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karras DJ, Ufberg JW, Heilpern KL, Cienki JJ, Chiang WK, Wald MM, Harrigan RA, Wald DA, Shayne P, Gaughan J, Kruus LK. Elevated blood pressure in urban emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12:835–843. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vanhoutte PM. Platelet-derived serotonin, the endothelium, and cardiovascular disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1991;17:S6–S12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linder L, Kiowski W, Bühler FR, Lüscher TF. Indirect evidence for release of endothelium-derived relaxing factor in human forearm circulation in vivo. Blunted response in essential hypertension. Circulation. 1990;81:1762–1767. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.6.1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berry CN, Lorrain J, Lochot S, Delahaye M, Lalé A, Savi P, Lechaire I, Ferrari P, Bernat A, Schaeffer P, Janiak P, Duval N, Grosset A, Herbert JM, O'Connor SE. Antiplatelet and antithrombotic activity of SL65.0472, a mixed 5-HT1B/5-HT2A receptor antagonist. Thromb Haemost. 2001;85:521–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ottervanger JP. Bleeding attributed to the intake of paroxetine. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:781–782. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.5.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ahmed BA, Jeffus B, Harney JT, Bukhari IS, Unal R, Lupashin VV, van der Sluijs P, Kilic F. Serotonin transamidates Rab4 and facilitates its binding to the C terminus of serotonin transporter. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9388–9398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706367200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mercado C, Ziu E, Kilic F. Communication between 5HT and small GTPases. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2011;11:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang DD, Bai Y, Gunst SJ. Silencing of p21-activated kinase attenuates vimentin phosphorylation on Ser-56 and reorientation of the vimentin network during stimulation of smooth muscle cells by 5-hydroxytryptamine. Biochem J. 2005;388:773–783. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li QF, Spinelli AM, Wang R, Anfinogenova Y, Singer HA, Tang DD. Critical role of vimentin phosphorylation at Ser-56 by p21-activated kinase in vimentin cytoskeleton signaling. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34716–34724. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607715200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmed B, Bukhari IA, Jeffus BC, Harney JT, Thyparambil S, Ziu E, Fraer M, Rusch NJ, Zimniak P, Lupashin V, Tang D, Kilic F. The cellular distribution of serotonin transporter is impeded on serotonin-altered vimentin network. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e4730. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 33.Duerschmied D, Canault M, Lievens D, Brill A, Cifuni SM, Bader M, Wagner DD. Serotonin stimulates platelet receptor shedding by tumor necrosis factor-alpha-converting enzyme (ADAM17) J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:1163–1171. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tschopp TB, Baumgartner HR. Defective platelet adhesion and aggregation on subendothelium exposed in vivo or in vitro to flowing blood of fawn-hooded rats and storage pool disease. Thromb Haemost. 1977;38:620–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raymond SL, Dodds WJ. Characterization of the fawn-hooded rat as a model for hemostatic studies. Thromb Diath Haemorrh. 1975;33:361–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Magro A, Bizios R, Catalfamo J, Blumenstock F, Rudofsky U. Collagen-induced rat platelet reactivity is enhanced in whole blood in both the presence and absence of dense granule secretion. Thromb Res. 1992;68:345–356. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(92)90093-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kirchmaier CM, Meyer M, Spangenberg P, Heller R, Haroske D, Breddin HK, Till U. Platelet membrane defects in fawn hooded bleeder rats. Thromb Res. 1990;57:353–360. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(90)90251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kelm S, Schauer R. Sialic acids in molecular and cellular interactions. Int Rev Cytol. 1997;175:137–240. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(08)62127-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brenner B, Harney JT, Ahmed BA, Jeffus BC, Unal R, Mehta JL, Kilic F. Plasma serotonin levels and the platelet serotonin transporter. J Neurochem. 2007;102:206–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vikens K, Farstad M, Nordrehaug JE. Serotonin is associated with coronary artery disease and cardiac events. Circulation. 1999;100:483–489. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.5.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kerr S, Brosnan MJ, McIntyre M, Reid JL, Dominiczak AF, Hamilton CA. Superoxide anion production is increased in a model of genetic hypertension: role of the endothelium. Hypertension. 1999;33:1353–1358. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.6.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Biondi ML, Agostoni A, Marasini B. Serotonin levels in hypertension. J Hypertens. 1986;4:S39–S41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davis RP, Szasz T, Garver H, Burnett R, Tykocki NR, Watts SW. One-month serotonin infusion results in a prolonged fall in blood pressure in the deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA) salt hypertensive rat. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2013;4:141–148. doi: 10.1021/cn300114a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rapport MM, Green AA, Page IH. Serum vasoconstrictor, serotonin; isolation and characterization. J Biol Chem. 1948;176:1243–1251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Guilluy C, Eddahibi S, Agard C, Guignabert C, Izikki M, Tu L, Savale L, Humbert M, Fadel E, Adnot S, Loirand G, Pacaud P. RhoA and Rho kinase activation in human pulmonary hypertension: role of 5-HT signaling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:1151–1158. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200805-691OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ziu E, Hadden C, Li Y, Lowery CL, III, Singh P, Ucer SS, Mercado C, Gu HH, Kilic F. Effect of serotonin on platelet function in cocaine exposed blood. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5945. doi: 10.1038/srep05945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Minuz P, Patrignani P, Gaino S, Seta F, Capone ML, Tacconelli S, Degan M, Faccini G, Fornasiero A, Talamini G, Tommasoli R, Arosio E, Santonastaso CL, Lechi A, Patrono C. Determinants of platelet activation in human essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2004;43:64–70. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000105109.44620.1B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Menon DV, Wang Z, Fadel PJ. Central sympatholysis as a novel countermeasure for cocaine-induced sympathetic activation and vasoconstriction in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:626–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.03.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eisenberg MJ, Mendelson J, Evans GT, Jr, Jue J, Jones RT, Schiller NB. Left ventricular function immediately after intravenous cocaine: A quantitative two dimensional echocardiographic study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993;22:1581–1586. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90581-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Senchenkova EY, Russell J, Almeida-Paula LD, Harding JW, Granger DN. Angiotensin II-mediated microvascular thrombosis. Hypertension. 2010;56:1089–1095. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.158220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kugelmass AD, Oda A, Monahan K, Cabral C, Ware JA. Activation of human platelets by cocaine. Circulation. 1993;88:876–883. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.3.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kolodgie FD, Virmani R, Cornhill JF, Herderick EE, Smialek J. Increase in atherosclerosis and adventitial mast cells in cocaine abusers: an alternative mechanism of cocaine-associated coronary vasospasm and thrombosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:1553–1560. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(91)90646-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moliterno DJ, Moliterno DJ, Lange RA, Gerard RD, Willard JE, Lackner C, Hillis LD. Influence of intranasal cocaine on plasma constituents associated with endogenous thrombosis and thrombolysis. Am J Med. 1994;96:492–496. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(94)90087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heesch CM, Wilhelm CR, Ristich J, Adnane J, Bontempo FA, Wagner WR. Cocaine activates platelets and increases the formation of circulating platelet containing microaggregates in humans. Heart. 2000;83:688–695. doi: 10.1136/heart.83.6.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rinder HM, Ault KA, Jatlow PI, Kosten TR, Smith BR. Platelet α-granule release in cocaine sers. Circulation. 1994;90:1162–1167. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.3.1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen R, Tilley MR, Wei H, Zhou F, Zhou FM, Ching S, Quan N, Stephens RL, Hill ER, Nottoli T, Han DD, Gu HH. Abolished cocaine reward in mice with a cocaine-insensitive dopamine transporter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9333–9338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600905103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kalinowski L, Matys T, Chabielska E, Buczko W, Malinski T. Angiotensin II AT1 receptor antagonists inhibit platelet adhesion and aggregation by nitric oxide release. Hypertension. 2002;40:521–527. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000034745.98129.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brown NJ, Vaughan DE. Prothrombotic effects of angiotensin. Adv Intern Med. 2000;45:419–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Unger T, Culman J, Gohlke P. (Ang II receptor blockade and end-organ protection: pharmacological rationale and evidence. J Hypertens. 1998;16:S3–S9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gkaliagkousi E, Ritter J, Ferro A. Platelet-derived nitric oxide signaling and regulation. Circ Res. 2007;101:654–662. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.158410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Taddei S, Virdis A, Ghiadoni L, Mattei P, Salvetti A. Effects of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition on endothelium-dependent vasodilatation in essential hypertensive patients. J Hypertens. 1998;16:447–456. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Muthalif MM, Karzoun NA, Gaber L, Khandekar Z, Benter IF, Saeed AE, Parmentier JH, Estes A, Malik KU. Angiotensin II-induced hypertension: contribution of Ras GTPase/Mitogen-activated protein kinase and cytochrome P450 metabolites. Hypertension. 2000;36:604–609. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rosenblum WI, El-Sabban F, Hirsh PD. Angiotensin Delays Platelet Aggregation After Injury of Cerebral Arterioles. Stroke. 1986;17:1203–1205. doi: 10.1161/01.str.17.6.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Iizuka K, Hamaue N, Machida T, Hirafuji M, Tsuji M. Beneficial effects of sarpogrelate hydrochloride, a 5-HT2A receptor antagonist, supplemented with pioglitazone on diabetic model mice. Endocr Res. 2009;34:18–30. doi: 10.1080/07435800902889685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nakamura K, Kariyazono H, Moriyama Y, Toyohira H, Kubo H, Yotsumoto G, Taira A, Yamada K. Effects of sarpogrelate hydrochloride on platelet aggregation, and its relation to the release of serotonin and P-selectin. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1999;10:513–519. doi: 10.1097/00001721-199912000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Villalón CM, Centurión D. Cardiovascular responses produced by 5-hydroxytriptamine: a pharmacological update on the receptors/mechanisms involved and therapeutic implications. Naunyn Schmiedebergs. Arch Pharmacol. 2007;376:45–63. doi: 10.1007/s00210-007-0179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shen FM, Wang J, Ni CR, Yu JG, Wang WZ, Su DF. Ketanserin-induced baroreflex enhancement in spontaneously hypertensive rats depends on central 5-HT(2A) receptors. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34:702–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Buch J. Urapidil, a dual-acting antihypertensive agent: Current usage considerations. Adv Ther. 2010;27:426–443. doi: 10.1007/s12325-010-0039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Southwick SM, Paige S, Morgan CA, 3rd, Bremner JD, Krystal JH, Charney DS. Neurotransmitter alterations in PTSD: catecholamines and serotonin. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 1999;4:242–248. doi: 10.153/SCNP00400242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]