Abstract

Maternal age is a risk factor for congenital heart disease even in the absence of any chromosomal abnormality in the newborn1-7. Whether the basis of the risk resides with the mother or oocyte is unknown. The impact of maternal age on congenital heart disease can be modeled in mouse pups that harbor a mutation of the cardiac transcription factor gene Nkx2-58. Here, reciprocal ovarian transplants between young and old mothers establish a maternal basis for the age-associated risk. A high-fat diet does not accelerate the effect of maternal aging, so hyperglycemia and obesity do not simply explain the mechanism. The age-associated risk varies with the mother's strain background, making it a quantitative genetic trait. Most remarkably, voluntary exercise, whether begun by mothers at a young age or later in life, can mitigate the risk when they are older. Thus, even when the offspring carry a causal mutation, an intervention aimed at the mother can meaningfully reduce their risk of congenital heart disease.

Congenital heart disease remains a leading cause of childhood morbidity and mortality despite dramatic clinical advances. Discoveries regarding the pathogenic mechanisms have likewise abounded, but translating the knowledge of causes in the embryo to improve outcomes will not be simple. The ideal would be to develop a broadly implemented prevention strategy, just as folic acid is prescribed to expectant mothers to prevent neural tube defects9. We therefore have focused upon genetic or environmental modifiers of heart defects caused by Nkx2-5 haploinsufficiency in the mouse embryo8,10. Mutations of the cardiac transcription factor NKX2-5 that cause congenital heart disease were first discovered in humans11,12. Modifiers, which affect risk but do not cause disease per se, can suggest therapies that do not necessarily target the main cause13.

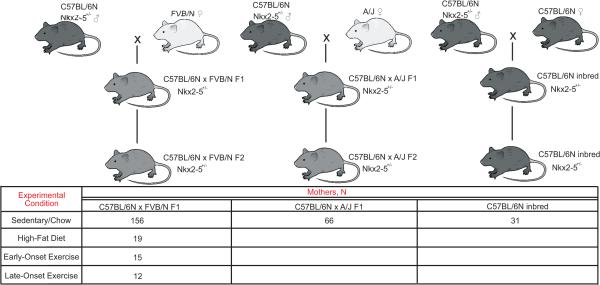

A substantial fraction of the ventricular septal defects (VSD) among Nkx2-5+/− mice can be attributed to the effect of modifiers8. The modifiers include genetic polymorphisms that quantitatively affect penetrance8,10. In the C57BL/6N X FVB/N hybrid strain background, maternal age also affects the risk of VSD in Nkx2-5+/− but not wild-type pups; Extended Data Fig. 1 depicts the breeding scheme. The risk is independent of genetic polymorphisms in the offspring and not due to chromosomal aneuploidy8. These laboratory and epidemiologic observations motivated investigation of the maternal age effect in the mouse model.

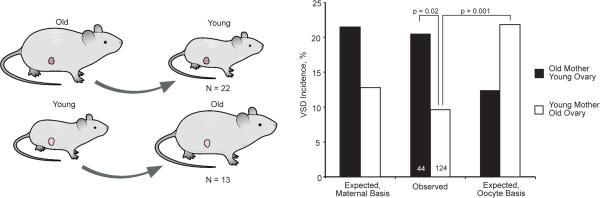

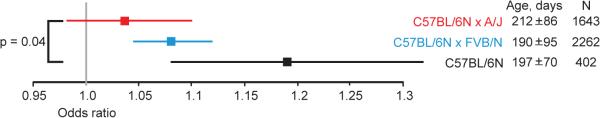

The basis of the maternal age effect could reside in either the mother or oocyte. To determine which, we performed reciprocal ovarian transplants between young and old mothers that were first generation (F1) hybrids of the inbred strains C57BL/6N and FVB/N (Fig. 1). F1 parents were bred to produce F2 offspring. The incidence of VSD was significantly greater among the Nkx2-5+/− offspring of older mothers bearing young ovaries. Next, we calculated the number of VSDs that would be expected for either a maternal or oocyte basis based upon the effect of maternal age that was quantified in the 2262 Nkx2-5+/− offspring of C57BL/6N X FVB/N F1 mothers who ovulated from their native ovaries. The observed numbers in each transplanted group were consistent with a maternal basis (Fig. 1). We focused on VSDs, the most common defect in Nkx2-5+/− mice, because their frequency provides sufficient power for the statistical analyses here8,10. Atrial septal defects (ASD), the second most common defect, showed a pattern consistent with a maternal basis, but their numbers were insufficient to draw statistical conclusions (Extended Data Fig. 2). The results point to a maternal pathway that either produces a factor or mediates a process that interacts with cardiac development in the mutant embryo. A harmful factor would rise with age, whereas a protective one would fall.

Fig. 1.

Reciprocal ovarian transplants between young and old mothers localize the basis of the maternal age-associated risk to the mother. The incidence of VSD for the offspring of old mothers with young ovaries is significantly greater than of young mothers with old ovaries. The observed incidence in the offspring of recipient mothers matches that expected for a maternal but not an oocyte basis of the age effect. The number of recipient mothers and the number of pups in each age group are shown.

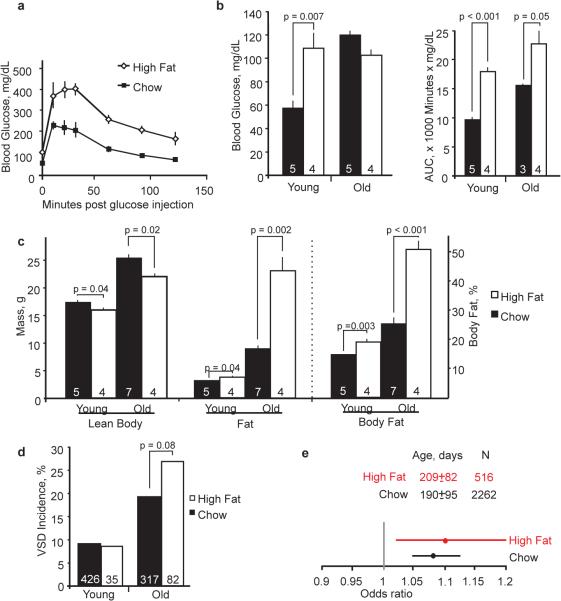

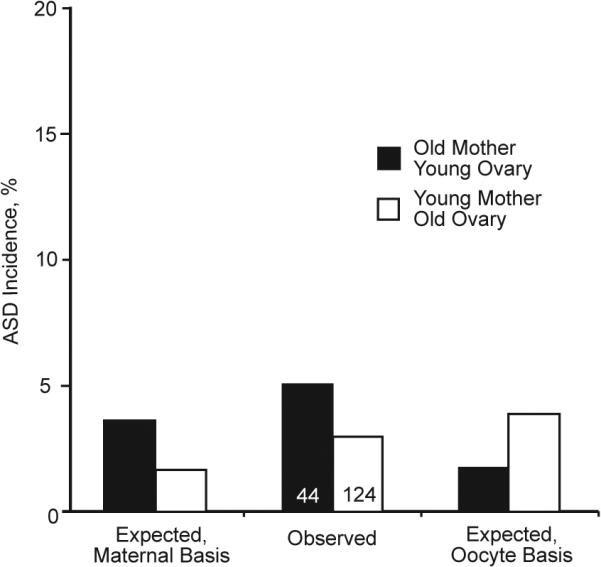

Factors related to diabetes or obesity are plausible suspects; both conditions are associated with aging and human congenital heart disease14. To assess their contribution to the maternal age-associated risk, we placed young females on a high-fat diet four weeks prior to mating. The mothers remained on the diet thereafter. Young mothers on a high-fat diet had impaired glucose tolerance and fasting hyperglycemia, yet their offspring had an incidence of VSD equal to those of mothers on a normal, chow diet (Fig. 2a, b, d). Old mothers developed marked adiposity in addition. Still, the incidence of VSD in their offspring was not significantly increased (Fig. 2c, d, and Extended Data Fig. 3). Despite large effects on glucose homeostasis and obesity, a high-fat diet did not significantly increase the maternal age-associated risk of defects (Fig. 2e and Extended Data Fig. 4). A logistic regression analysis that considered an interaction between diet and age also failed to detect an effect. Any potential effect of the high-fat diet on the maternal-age associated risk is small relative to the effects on glycemic indices or body composition.

Fig. 2.

A high-fat diet does not accelerate the onset of the maternal age effect. (a) A high-fat diet causes a higher peak glucose and impaired clearance in glucose tolerance tests. Data are shown here from young mothers. (b) A high-fat diet induces hyperglycemia in young mothers and impaired glucose tolerance in young and old mothers, as quantified by the area under the curve (AUC) in glucose tolerance tests. (c) Lean body mass decreases with a high-fat diet, while fat mass and percentage increases. Marked adiposity develops in old mothers on a high-fat diet. (d) The incidences of VSD in the offspring of young mothers are the same whether on a high-fat or normal diet. The incidence for the offspring of old mothers on a high-fat diet is not significantly increased. Young and old mothers are defined as <100 and >300-days old. Glucose tolerance tests and MRI quantification of body composition were performed on a subset of the 19 high-fat or 156 chow-diet fed mothers who produced the offspring for analysis. (e) The maternal age-associated risk is unaffected by a high-fat diet. Odds ratios are presented with the 95% confidence interval; the relative widths of the confidence intervals are related to the sample sizes. The age of the mothers (mean ± S.D.) and the number of offspring in each cohort are shown.

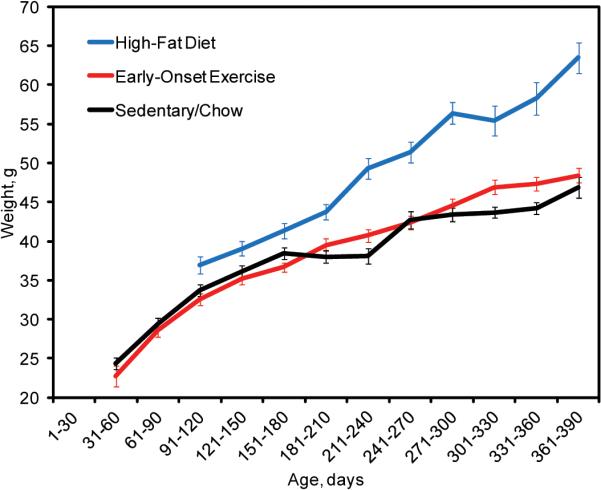

Most epidemiologic studies identify maternal age as a risk factor for congenital heart disease, but the risk is not always detected perhaps because of genetic variation among populations6,15,16. We thus compared the maternal age-associated risk in three mouse strain backgrounds: the inbred C57BL/6N and the F1 hybrids of C57BL/6N X A/J and C57BL/6N X FVB/N (Extended Data Fig. 1). The inbred C57BL/6N strain bears the greatest risk. That risk is significantly greater than in C57BL/6N X A/J, which shows no significant risk. The maternal-age associated risk in C57BL/6N X FVB/N is significant and intermediate to the other two backgrounds (Fig. 3). The maternal age-associated risk is a quantitative genetic trait. For example, the net effect of A/J polymorphisms is to reduce the risk associated with aging, whereas C57BL/6N polymorphisms generally increase risk. Genetic polymorphisms may affect the activity of the maternal factor hypothesized to interact with embryonic cardiac development.

Fig. 3.

The maternal age-associated risk of VSD is a quantitative genetic trait. Risk is significantly greater in the inbred C57BL/6N strain than in the C57BL/6N X A/J F1 hybrid. The C57BL/6N X FVB/N F1 hybrid bears intermediate risk. Odds ratios are presented with the 95% confidence interval; the relative widths of the confidence intervals are related to the sample sizes. The age of mothers (mean ± S.D.) and the number of offspring in each cohort are shown.

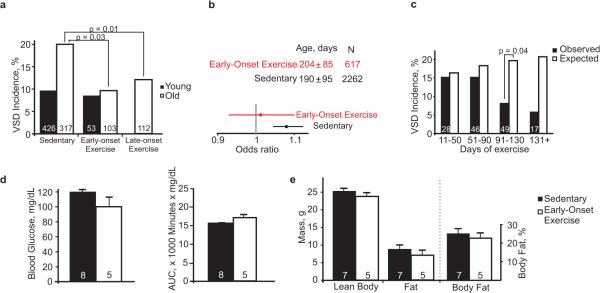

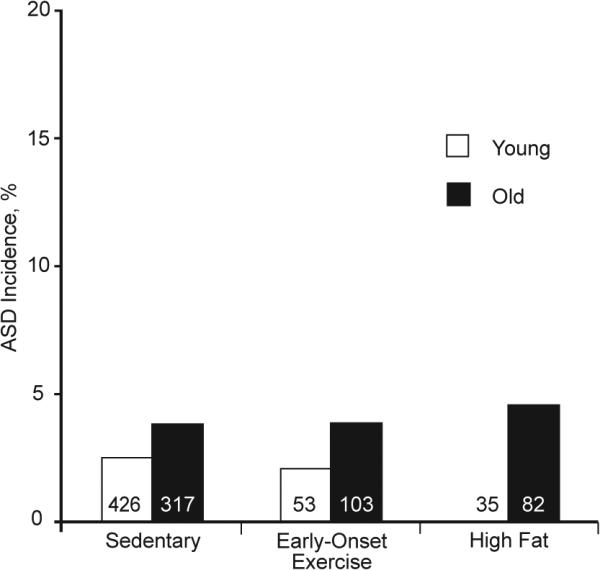

A/J and C57BL/6 are known for their phenotypic differences in a number of complex metabolic traits, including the effects of diet17,18. We thus wondered whether exercise, which has beneficial effects on metabolism, could decrease risk just as A/J polymorphisms decrease the risk of adverse metabolic phenotypes. Running wheels were placed in the cages of C57BL/6N X FVB/N F1 mice at the onset of breeding when the females were 4-weeks old. The mice were allowed to run ad libitum during their entire reproductive lifespan19. Early-onset exercise did not lower the incidence of VSD in the Nkx2-5+/− offspring of young mothers but did in those of old mothers (Fig. 4a). When all the offspring of mothers from young to old age were included in a logistic regression analysis, the maternal-age associated risk was insignificant in the setting of early-onset exercise (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Exercise can mitigate the risk associated with maternal aging. Running wheels were placed in breeding cages when mothers were 4-weeks or 8-months old (early- or late-onset exercise groups). (a) Both early and late-onset exercise decrease the incidence of VSD for the offspring of old compared to that of young mothers. The number of mouse pups in each group is shown. (b) Early-onset exercise makes the risk associated with aging insignificant. Odds ratios are presented with the 95% confidence interval; the relative widths of the confidence intervals are related to the sample sizes. The age of their mothers (mean ± S.D.) and the number of offspring in each cohort are shown. (c) The incidence of VSD is shown binned according to the number of days a mother in the late-onset group had exercised by the pup's birthdate. The expected incidences are calculated for age-matched, sedentary control mothers. Three months of exercise prior to conception results in a detectable reduction in the incidence of VSD. (d) Early-onset exercise does not alter fasting glucose levels or glucose tolerance in old mothers. (e) Lean and fat body mass and body fat percentage are also not appreciably affected. Glucose tolerance tests and MRI quantification of body composition were performed on a subset of the mothers in the early-onset exercise and sedentary groups.

Early-onset exercise clearly reduces risk for Nkx2-5+/− offspring but may be difficult to implement in clinical practice. We therefore assessed the effect of exercise beginning in late adulthood. Running wheels were placed in cages when the mothers were 8 months old. The subsequent incidence of VSD was significantly reduced in the Nkx2-5+/− offspring of mothers older than 300 days. Late-onset exercise reduced the incidence nearly as much as early-onset exercise (Fig. 4a). Consistent with the multifactorial basis of a congenital heart defect, exercise mitigates the fraction of risk associated with maternal aging but does not eliminate risk entirely, as shown by the equivalent incidences of VSD in the offspring of exercised and sedentary young mothers.

To estimate the duration of exercise sufficient for an effect, the observed incidence of VSD was compared to the expected in a range of intervals binned according to the number of days a mother had exercised by a pup's birth date. Given a 20-day gestational period, 3 months of exercise prior to conception exerts a detectable effect on incidence (Fig. 4c). Variables not examined here, such as the mother's age at the onset of exercise and the intensity of exercise, could affect the magnitude of the effect. Nevertheless, a modest duration of exercise appears sufficient to reduce the risk of congenital heart disease.

The benefit of exercise for the offspring is not associated with overt or large changes in the mother. Neither early- nor late-onset exercise significantly affected glucose metabolism, lean or fat body mass or weight in old mothers (Fig. 4d, e, Extended Data Fig. 3). Furthermore, body weight was not independently associated with risk under any of the experimental conditions, i.e., sedentary control, high-fat diet, early- or late-onset exercise. In humans, good evidence indicates that maternal diabetes and obesity are risk factors for congenital heart disease14. The fraction of children of mothers who have diabetes or obesity who actually have a heart defect is still small, however, so the true risk factor may be present in just a subset of women. Exercise may ameliorate a risk factor associated with aging, dysglycemia or obesity without a noticeable effect on glucose metabolism or body composition in the mouse mother.

The present results reveal a maternal pathway that could potentially be targeted to prevent congenital heart disease in offspring who carry a deleterious mutation. Whether this pathway affects the development of defects other than VSD or that are not caused by Nkx2-5 mutation remains unanswered, although consistent evidence supports a maternal-age associated risk for ASD in the mouse (Extended Data Fig. 2 and 4) and other defects in humans. Very large studies are necessary to prove or exclude confidently a maternal age-associated risk for less common defects. Experimental dissection of the pathway may be a more efficient means forward. The results could indicate whether distinct defects should be analyzed separately and help to focus the aims of human studies. Well-known pathways may not be involved, given that deranged glucose homeostasis and obesity do not exacerbate the maternal age effect. Interestingly, maternal genetic polymorphisms in other metabolic pathways have recently been associated with the risk of conotruncal heart defects in humans20. A maternal genetic basis for the age-associated risk in Nkx2-5+/− pups likewise supports the concept of Gene X Gene interactions between the mother and embryo. The present results do not exclude the possibility of other complex molecular, genetic and epigenetic mechanisms, but mapping the genes that affect risk could provide a foothold into the maternal pathway. In addition, the effect of exercise provides a functional clue. Like aging, exercise has complex effects on physiology and metabolism. Exercise and aerobic fitness affect the concentration of dozens of metabolites21-26. Any of them could be the hypothesized age-related factor. The pertinent factor or pathway in the mouse, however, must fit a profile delimited by aging and genetic background.

METHODS

Mouse strains

The C57BL/6N and FVB/N inbred strains were purchased from Charles River, and the A/J strain from the Jackson Laboratory. Nkx2-5+/− mice were maintained in the C57BL/6N background; Nkx2-5+/− males were crossed to FVB/N or A/J females to produce first generation (F1) hybrids10,27. Nkx2-5+/− F1 mice were then crossed to produce the F2 offspring (Extended Data Figure 1). No randomization was necessary among genetically identical mice. The animal studies committee at Washington University School of Medicine approved the experiments.

Preparation and phenotyping of newborn mouse hearts

Newborn mouse pups were collected within hours of birth. Their hearts were fixed in formalin, and the pups were genotyped for the Nkx2-5 knockout allele. Nkx2-5+/− hearts were embedded in paraffin, serially sectioned at 6 micron thickness and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The sections were examined for heart defects as previously described10. Phenotyping was performed by individuals blinded to the age of a pup's mother or in the transplantation experiment the ovary as well. Every heart that was phenotyped is included in statistical analyses.

Ovarian Transplantation

Mice were anesthetized with a cocktail (0.5-0.7 ml/kg) of 3:3:1 ketamine (100 mg/ml), xylazine (20 mg/ml) and acepromazine (10 mg/ml) via intraperitoneal injection. A small incision was made in the dorsolateral flank to access the ovarian bursa. The ovary was removed from the donor and then transplanted into the recipient. The native, contralateral ovary of the recipient was left in place, while the oviduct was ligated. Transplants were performed between C57BL/6N X FVB/N F1 females that were either old (range 244-377 days, mean 317) or young (range 30-81 days, mean 48). The recipient females were allowed to recover for three weeks before breeding commenced. Pregnant females were noted to carry their fetuses in the uterine horn on the same side as the transplanted ovary.

High-fat diet

Weanling Nkx2-5+/− C57BL/6N x FVB/N F1 females were placed on a high-fat diet for 4 weeks prior to the onset of breeding. The mice remained on the diet while breeding. Calories in the diet derived from 59% fat, 25% carbohydrate, and 15% protein (AIN-76A w/58% Fat Energy/Sucrose/Red, catalog # 1810835, Test Diet). Calories in the normal, control diet derived from 13% fat, 62% carbohydrate, and 25% protein (Pico Rodent Diet 20, catalog # 0007688, Lab Diet).

Exercise

Running wheels were placed in breeding cages when the females were either 4-weeks (early-onset group) or 8-months old (late-onset). The mice ran ad libitum for the remainder of their reproductive lives.

Intraperitoneal Glucose Tolerance Testing

Mice were fasted overnight (14 h) on paper bedding prior to glucose challenge (2 g/kg intraperitoneal). Blood was obtained from the tail vein for glucometry. Samples were measured with a Bayer Contour TS glucometer before and at 10, 20, 30, 60, 90, and 120 minutes after injection.

Lean and Fat Body Mass Quantification

Lean and fat body mass was measured in live mice by quantitative magnetic resonance imaging on an EchoMRI 3-in-1 instrument (Echo Medical Systems, Houston, TX). Fat body mass measurements were calibrated against canola oil standards.

Statistics

The maternal-age associated risk of a defect within an experimental condition was calculated by logistic regression analysis. The phenotype of a pup, e.g., VSD present or normal, was the dependent variable, and the mother's age in months on the pup's birthdate was the independent variable. The data were fit to the inverse of the logistic function or logit using the Generalized Linear Model in R (http://www.r-project.org/). Fitting yielded an estimate of the maternal age coefficient, from which the odds ratio is calculated. Odds ratios are reported with the 95% confidence interval.

For the reciprocal ovarian transplant and late-onset exercise experiments, the expected incidence of a defect was calculated from the estimates of the coefficients in the logit for the C57BL/6N X FVB/N sedentary control group and either the age of the mother or ovary for every pup. The probability of a defect, as given by the logistic function, was calculated for each observed pup. The sum of probabilities across all the pups was the expected number for the experimental group, given the hypothesized or null model. The expected and observed numbers of defects were compared in a Chi-square goodness-of-fit test. To assess the effect of other variables, such as genetic background, diet or the interaction of either with age, the variables were included in the logistic function as covariates in addition to maternal age. The significance of a covariate was determined using the Generalized Linear Model in R.

Two-sided t-tests were performed for blood glucose and body composition measurements.

Experimental sample sizes in the ovarian transplantation, high-fat diet, and exercise experiments and analysis of the C57BL/6N strain were planned based on the incidences of VSD in the offspring of young and old C57BL/6N X FVB/N F1 mothers. Every heart collected for an experimental condition was included in the statistical analysis unless poor histology precluded a diagnosis.

Results are reported as mean ± S.E.M. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Breeding scheme and experimental conditions.

Nkx2-5+/− offspring from several maternal genetic backgrounds and experimental conditions were phenotyped. Nkx2-5+/− C57BL/6N males were crossed to FVB/N or A/J females to produce F1 hybrids. The cross to a C57BL/6N female maintains the inbred strain. Nkx2-5+/− F1 hybrids were intercrossed to produce the F2 progeny. The hearts of newborn Nkx2-5+/− F2 pups were phenotyped to calculate the incidence of a defect and the effect of maternal age. C57BL/6N X FVB/N F1 hybrid mothers were bred in either sedentary/chow, high-fat diet, early- or late-onset exercise conditions. C57BL/6N X A/J F1 hybrid and C57BL/6N inbred mothers were studied only in the sedentary/chow condition. The number of mothers in each cross and experimental condition that were used to produce pups in this study are shown.

Extended Data Figure 2. Incidences of ASD in the reciprocal ovarian transplant experiment.

The relative incidences of ASD in the reciprocal ovarian transplant experiment are consistent with a maternal basis of the age-associated effect. The differences that were significant in the VSD data, however, are not here because of the lower incidence of ASD, as depicted by the Y-axis drawn on a scale comparable to that for VSD. The total number of pups in each group is shown.

Extended Data Figure 3. Growth charts for C57BL/6N X FVB/N F1 mothers under sedentary, early-onset exercise and high-fat diet conditions.

C57BL/6N X FVB/N F1 mothers on a high-fat diet develop marked obesity as they age. They weigh substantially more than mothers in the sedentary or early-onset exercise groups. Mothers in the latter two groups weigh the same.

Extended Data Figure 4. ASD incidences in the offspring of C57BL/6N X FVB/N mothers.

Maternal age may affect the risk of ASD, but the lower incidence of ASD and other defects less common than VSD preclude firm statistical conclusions. For example, the incidences of ASD are shown for the Nkx2-5+/− offspring of young and old C57BL/6N X FVB/N mothers in the sedentary, early-onset exercise, and high-fat diet conditions. The Y-axis is drawn on a scale comparable to that for VSD incidence. ASD incidences are higher, but not significantly, among the offspring of old mothers compared to young mothers. The incidences are not significantly different between experimental conditions. The total number of pups in each group is shown.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

CES was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Awards from the Developmental Cardiology and Pulmonary Training Program (NIH T32 HL007873). PYJ is an Established Investigator of the American Heart Association and the Lawrence J. & Florence A. DeGeorge Charitable Trust. This work was supported by the Children's Discovery Institute of Washington University and St. Louis Children's Hospital, the Children's Heart Foundation, and the NIH (R01 HL105857). The Washington University Digestive Diseases Research Core Center provided histology services and is supported by the NIH (P30 DK52574). MRI studies were performed in the Washington University Diabetes Research Center, which is supported by the NIH (P30 DK020579). We thank Drs. Jeffrey Magee, Joshua Rubin, David Rudnick, and Alan Schwartz for comments.

Footnotes

CONTRIBUTIONS:

C.E.S., D.B.W. and P.Y.J. designed experiments. C.E.S., S.D.R., R.A.M., M.T.D., H.L., A.K.H.

A.A.P., M.M.G., and P.Y.J. executed experiments. C.E.S. and P.Y.J. interpreted experiments.

C.E.S. and P.Y.J. wrote the manuscript. D.B.W. critically reviewed the paper.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS:

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Forrester MB, Merz RD. Descriptive epidemiology of selected congenital heart defects, Hawaii, 1986-1999. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2004;18:415–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2004.00594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hollier LM, Leveno KJ, Kelly MA, MCIntire DD, Cunningham FG. Maternal age and malformations in singleton births. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000;96:701–706. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01019-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kidd SA, Lancaster PA, McCredie RM. The incidence of congenital heart defects in the first year of life. J. Paediatr. Child Health. 1993;29:344–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1993.tb00531.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Materna-Kiryluk A, et al. Parental age as a risk factor for isolated congenital malformations in a Polish population. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 2009;23:29–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2008.00979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller A, Riehle-Colarusso T, Siffel C, Frias JL, Correa A. Maternal age and prevalence of isolated congenital heart defects in an urban area of the United States. Am. J. Med Genet. A. 2011;155A:2137–2145. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pradat P, Francannet C, Harris JA, Robert E. The epidemiology of cardiovascular defects, part I: a study based on data from three large registries of congenital malformations. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2003;24:195–221. doi: 10.1007/s00246-002-9401-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reefhuis J, Honein MA. Maternal age and non-chromosomal birth defects, Atlanta--1968-2000: teenager or thirty-something, who is at risk? Birth Defects Res. A Clin. Mol. Teratol. 2004;70:572–579. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winston JB, et al. Complex Trait Analysis of Ventricular Septal Defects Caused by Nkx2-5 Mutation. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2012;5:293–300. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.961136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MRC Vitamin Study Research Group Prevention of neural tube defects: results of the Medical Research Council Vitamin Study. Lancet. 1991;338:131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winston JB, et al. Heterogeneity of genetic modifiers ensures normal cardiac development. Circulation. 2010;121:1313–1321. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.887687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schott JJ, et al. Congenital heart disease caused by mutations in the transcription factor NKX2-5. Science. 1998;281:108–111. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5373.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benson DW, et al. Mutations in the cardiac transcription factor NKX2.5 affect diverse cardiac developmental pathways. J. Clin. Invest. 1999;104:1567–1573. doi: 10.1172/JCI8154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nadeau JH. Modifier genes in mice and humans. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2001;2:165–174. doi: 10.1038/35056009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenkins KJ, et al. Noninherited risk factors and congenital cardiovascular defects: current knowledge: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation. 2007;115:2995–3014. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.183216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baird PA, Sadovnick AD, Yee IM. Maternal age and birth defects: a population study. Lancet. 1991;337:527–530. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91306-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loane M, Dolk H, Morris JK. Maternal age-specific risk of non-chromosomal anomalies. BJOG. 2009;116:1111–1119. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burrage LC, et al. Genetic resistance to diet-induced obesity in chromosome substitution strains of mice. Mamm. Genome. 2010;21:115–129. doi: 10.1007/s00335-010-9247-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singer JB, et al. Genetic dissection of complex traits with chromosome substitution strains of mice. Science. 2004;304:445–448. doi: 10.1126/science.1093139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen DL, et al. Cardiac and skeletal muscle adaptations to voluntary wheel running in the mouse. J. Appl. Physiol. 2001;90:1900–1908. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.5.1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li M, et al. Detecting maternal-fetal genotype interactions associated with conotruncal heart defects: a haplotype-based analysis with penalized logistic regression. Genet. Epidemiol. 2014;38:198–208. doi: 10.1002/gepi.21793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bye A, et al. Serum levels of choline-containing compounds are associated with aerobic fitness level: the HUNT-study. PLoS. One. 2012;7:e42330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chorell E, Svensson MB, Moritz T, Antti H. Physical fitness level is reflected by alterations in the human plasma metabolome. Mol. Biosyst. 2012;8:1187–1196. doi: 10.1039/c2mb05428k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krug S, et al. The dynamic range of the human metabolome revealed by challenges. FASEB J. 2012;26:2607–2619. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-198093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis GD, et al. Metabolic signatures of exercise in human plasma. Sci. Transl. Med. 2010;2:33ra37. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lustgarten MS, et al. Identification of serum analytes and metabolites associated with aerobic capacity. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2013;113:1311–1320. doi: 10.1007/s00421-012-2555-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mukherjee K, et al. Whole blood transcriptomics and urinary metabolomics to define adaptive biochemical pathways of high-intensity exercise in 50-60 year old masters athletes. PLoS. One. 2014;9:e92031. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanaka M, Chen Z, Bartunkova S, Yamasaki N, Izumo S. The cardiac homeobox gene Csx/Nkx2.5 lies genetically upstream of multiple genes essential for heart development. Development. 1999;126:1269–1280. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.6.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]