Abstract

A 59-year-old kidney recipient was diagnosed with a late onset of severe chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy and almost fully recovered after stopping tacrolimus and one course of intravenous immunoglobulin treatment. Unique features of this patient are the unusually long time lapse between initiation of tacrolimus and the adverse effect (10 years), a strong causality link and several arguments pointing toward an inflammatory etiology. When facing new neurological signs and symptoms in graft recipients, it is important to bear in mind the possibility of a drug-induced adverse event. Discontinuation of the suspect drug and immunomodulation are useful treatment options.

Keywords: adverse event, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy, tacrolimus

Introduction

Safety concerns about tacrolimus include neurological adverse events (NAEs) similar to other calcineurin inhibitors [1–4]. In a 1991 prospective study (n = 44), NAEs were reported in 32% of liver transplant recipients on tacrolimus [5]. In 2007, a large prospective study (n = 1645) reported NAEs to be present in 10–15% of patients treated with calcineurin inhibitors for 1 year [6]. We report here a kidney transplant recipient who developed a life-threatening demyelinating sensorimotor polyneuropathy while on tacrolimus.

Case report

A 59-year-old African-born female patient underwent renal deceased donor heterotopic transplantation in August 2000. Cytomegalovirus serology was negative in the donor, positive in the recipient; Epstein-Barr virus serology was positive in both donor and recipient. Initial immunosuppression consisted of basiliximab 20 mg at days 0 and 4, then cyclosporine (targeted plasma level 150–200 µg/L), azathioprine (1–2 mg/kg/day) and steroids. At day 7, cyclosporine was switched to tacrolimus (targeted plasma level 8–10 µg/L) because of digestive intolerance. Two episodes of mild rejection at months (M) 4 and 106 were successfully treated.

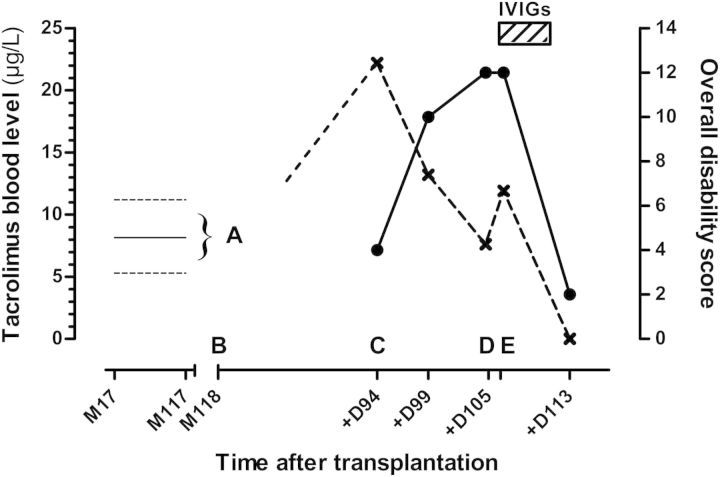

Otherwise, creatinine and tacrolimus serum levels remained stable over many years (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Tacrolimus whole blood levels (cross symbols) and clinical findings over time following transplantation. 0 = graft; M = month post-graft; D = days after 1st neurological manifestations; IVIGs=intravenous immunoglobulins. Overall disability sum score (filled circles) was retrospectively calculated according to Merkies ISJ et al., J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2002. Tacrolimus whole blood levels were quantified by means of an immunoassay. (A) Variations of tacrolimus levels from M17 to M117 (full line = mean level, dotted lines = highest and lowest levels ever measured). (B) Onset of neurological manifestations at M118 = D0. (C) First neurological impairment at D94. (D) Switch from tacrolimus to sirolimus and beginning of IVIGs at D105. (E) First clinical improvement at D106.

Ten years after the graft, at M118, the patient complained about painful paresthesias first in both hands, and 1 month later in her feet. At M120, neurological examination revealed distal loss of touch and vibratory sensations of four extremities. The sensory nerve action potentials (SNAPs) were absent in the ulnar, median and sural nerves (Tables 1 and 2). At M121, the patient was hospitalized for stance and gait disorders. General examination was normal, tendon reflexes were preserved, but all sensory modalities were reduced in her distal upper and lower limbs. On the fourth hospital day, tacrolimus serum level was found to be elevated at 22.2 µg/L. The patient was found to have been erroneously receiving a double dose since admission. This was corrected and 5 days later, the tacrolimus level had almost normalized at 13.2 µg/L, but the neurological manifestations worsened. A repeat nerve conduction study demonstrated findings consistent with motor neuronal demyelination and absent SNAPs (Table 1). The patient also developed hypertension, tachycardia, profuse sweating, alternating diarrhea–constipation, urinary incontinence, multiple electrolyte disorders consistent with dysautonomia and delirium related to severe hyponatremia (117 mmol/L, normal range 135–145 mmol/L) and opiate toxicity. Results of extensive laboratory and radiology studies were all negative. Two days later, intravenous infusions of immunoglobulins (IVIGs) were started (2 g/kg over 4 days), and tacrolimus was switched to sirolimus. With further supportive treatment, all symptoms improved rapidly over the next 3 weeks, and the patient was discharged home after a 2-month hospital stay (M123). Two months later (M125), she was independent in all activities of daily living; however, diffuse hyporeflexia, bilateral hypoesthesia in a stocking and glove distribution with distal reduction of vibration sense, with some gait and Romberg unsteadiness, were still present.

Table 1.

Results of nerve conduction studies (right side unless otherwise mentioned) at months 2.5 (A), 4 (B) and 7 (C) after the onset of neurological manifestationsa

| Nerve | Recording site | Parameters | A | B | C | Normal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motor studies | ||||||

| Median | Abductor pollicis brevis | Distal latency (ms) | 4.5 | 17.4 | <4.0 | |

| Amplitude (mV) | 6.8 | 0.2 | >5 | |||

| Duration (ms) | 10 | 37.8 | <6 | |||

| CV (m/s) | 52 | 0 | >50 | |||

| Tibial | Abductor hallucis | Distal latency (ms) | NR | 0 | <6.5 | |

| Amplitude (mV) | >3 | |||||

| Peroneal | Extensor digitorum brevis (Tibialis anterior) | Distal latency (ms) | 7.5 | 0(6) | 12 | <6.0 (<2.0) |

| Amplitude (mV) | 0.4 | (0.1) | 0.4 | >3 (>4) | ||

| Duration (ms) | (15) | 15 | <6 (<8) | |||

| F-wave latency (ms) | 0 | <52 | ||||

| Sensory studies | ||||||

| Median (digit 2) | Wrist | Amplitude (μV) | 0 | NR | >7 | |

| Sural | Ankle (right and left) | Amplitude (μV) | 0 | 0 | 0 | >5 |

aData are all abnormal, characterized by prolonged distal motor latencies and desynchronization of the motor responses, and absence of sensory responses, suggestive of sensorimotor demyelinating neuropathy—ms, milliseconds; μV or mV, micro or millivolts; m/s, metre/second; CV, conduction velocity; NR, not recorded; 0, absent.

Table 2.

Main characteristics of the 12 reported cases of tacrolimus-induced neuropathy (references in text)a

| References | Sex, age in years | Type of graft | Tacrolimus treatment details | Symptoms onset (time after transplant) | Clinical signs | Type of conduction abnormalities | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ayres et al. [8] | Male, 31 | Liver | tacrolimus 0.3 mg/kg daily from day 7 after transplant | D8 | Flaccid quadriparesis; Renal failure | Motor axonal | Complete resolution within a few days | Complete recovery |

| Ayres et al. [8] | Male, 58 | Liver | po from D7 on, 0.3 mg/kg/d | D8 | Flaccid quadriparesis | Motor, axonal | Tacrolimus withdrawal | Complete recovery |

| Wilson et al. [15] | Male, 57 (diabetes mellitus) | Liver | None given | Shortly after | Paresthesias, and foot drops over 6 months | Multifocal, demyelinating | PLEX over 10 days | Improvement over months |

| Wilson et al. [15] | Male, 60 | Liver | None given | D14 | Distal paresthesias, walking difficulties over 2 months | Multifocal, demyelinating | PLEX over 10 days, and IVIGs | Improvement over months |

| Wilson et al. [15] | Male, 35 (alcoholic cirrhosis) | Liver | None given | D14 | Distal paresthesias with weakness, bedridden | Sensori-motor, axonal | IVIGs over 3 days | Improvement over 3 weeks, then lost to follow-up |

| Bronster et al. [11] | Male, 45 | Liver | Complex (see reference) | Over the 4 months following transplant | Disabling distal paresthesias | Generalized, demyelinating | Tacrolimus switched to cyclosporine | Improvement over weeks |

| Laham et al. [14] | Male, 40 | Kidney | Complex (see reference) | D14 | Distal muscle weakness | Multifocal, demyelinating | Withdrawal of tacrolimus; IVIGs over 5 days | Recovery within 19 weeks |

| Boukriche et al. [10] | Male, 52 | Lung | Tacrolimus plasma level elevated | D3 | Distal paresthesias, weakness and inability to walk | Sensori-motor, axonal | Transient cessation of tacrolimus | Improvement over months |

| Bhagavati et al. [9] | Female, 44 | Kidney | 3 mg bid | 10 months | Facial twitching and numbness, gait dysbalance | Demyelinating, involving limbs and cranial nerves | IVIGs over 5 days | Improvement over months, recovery after 3 months |

| Bhagavati et al. [9] | Male, 53 | Kidney | 12 mg, then 7 mg bid | Immediately | None given | Diffuse, predominantly axonal neuropathy | Tacrolimus dose reduced to 2 mg bid | Resolution after 5–6 weeks |

| De Weerdt et al. [12] | Female, 44 | Liver and pancreas | Tacrolimus 0.04-0.08 mg/kg | D9 | Distal muscle weakness | Asymmetric motor axonal | Tacrolimus dose reduced, IVIGs over 5 days | Improvement over months (walking aids after 2 years) |

| Labate et al. [13] | Female, 56 | Heart | Tacrolimus 5 mg bid | 2 months | Progressive paresthesias in the lower limbs | Symmetric, sensorimotor demyelinating | Tacrolimus switched to cyclosporine | Improvement over months |

aD, days post-graft; iv, intravenous; IVIGs, intravenous immunoglobulins.

Discussion

Ten years after the graft, this 59-year-old kidney transplant recipient experienced a life-threatening sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy strongly suggesting a diagnosis of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (CIDP). A tacrolimus-induced adverse event has been judged probable (score of 5/13 according to the Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale) [7].

We identified 12 other published reports of tacrolimus-related polyneuropathy [8–15]. The onset was within the first 3 months after initiation of tacrolimus in most of the patients, but one presented with symptoms after 10 months of treatment. Tacrolimus blood levels were described as over the target range in five cases. Demyelinating type of neuropathy was predominant. In contrast, tacrolimus has been used as an immunosuppressant treatment in two cases of primary CIDP [16, 17].

The underlying mechanism in our patient is probably inflammatory and non-toxic, given the fast and excellent response to the single course of IVIGs. The cause of inflammation is undetermined and some undiagnosed infection remains a possibility. Autoimmune damage is another possibility, a tacrolimus-triggered event in the context of dysimmunity in this graft recipient being possible.

In summary, our case contributes quite unique features of what is already known on tacrolimus-induced neuropathy:

1. The adverse effect occurred 10 years after initiation of tacrolimus.

2. A causal role of tacrolimus is suggested by a suggestive temporal relationship, long-term response after cessation of treatment, exclusion of other causes, some degree of dose–response relationship during transient overdosage and consistency with previously published cases.

3. Tacrolimus could be switched safely to sirolimus. Sirolimus-induced neurotoxicity has rarely been described [18, 19]. In our patient, it has been well tolerated so far after an ongoing treatment of 18 months.

In conclusion, this case illustrates that a drug-induced adverse reaction may occur a long time after starting tacrolimus. Early discontinuation of the offending drug and immunomodulation by IVIGs are the key components of management given the potential for a life-threatening course.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Alessiani M, Cillo U, Fung JJ, et al. Adverse effects of FK 506 overdosage after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 1993;25:628–634. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bechstein WO. Neurotoxicity of calcineurin inhibitors: impact and clinical management. Transplant Int. 2000;13:313–326. doi: 10.1007/s001470050708. doi:10.1111/j.1432-2277.2000.tb01004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eidelman BH, Abu-Elmagd K, Wilson J, et al. Neurologic complications of FK 506. Transplant Proc. 1991;23:3175–3178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Said G. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2006;16:293–303. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2006.02.008. doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wijdicks EF, Wiesner RH, Dahlke LJ, et al. FK506-induced neurotoxicity in liver transplantation. Ann Neurol. 1994;35:498–501. doi: 10.1002/ana.410350422. doi:10.1002/ana.410350422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ekberg H, Tedesco-Silva H, Demirbas A, et al. Reduced exposure to calcineurin inhibitors in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2562–2575. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067411. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa067411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239–245. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.154. doi:10.1038/clpt.1981.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayres RC, Dousset B, Wixon S, et al. Peripheral neurotoxicity with tacrolimus. Lancet. 1994;343:862–863. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92070-2. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(94)92070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhagavati S, Maccabee P, Muntean E, et al. Chronic sensorimotor polyneuropathy associated with tacrolimus immunosuppression in renal transplant patients: case reports. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:3465–3467. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.06.088. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.06.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boukriche Y, Brugiere O, Castier Y, et al. Severe axonal polyneuropathy after a FK506 overdosage in a lung transplant recipient. Transplantation. 2001;72:1849–1850. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200112150-00026. doi:10.1097/00007890-200112150-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bronster DJ, Yonover P, Stein J, et al. Demyelinating sensorimotor polyneuropathy after administration of FK506. Transplantation. 1995;59:1066–1068. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199504150-00029. doi:10.1097/00007890-199504150-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Weerdt A, Claeys KG, De Jonghe P, et al. Tacrolimus-related polyneuropathy: case report and review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008;110:291–294. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2007.10.014. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Labate A, Morelli M, Palamara G, et al. Tacrolimus-induced polyneuropathy after heart transplantation. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33:161–162. doi: 10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181dc4f43. doi:10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181dc4f43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laham G, Vilches A, Jost L, et al. Acute peripheral demyelinating polyneuropathy and acute renal failure after administration of FK506. Medicina (B Aires) 2001;61:445–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson JR, Conwit RA, Eidelman BH, et al. Sensorimotor neuropathy resembling CIDP in patients receiving FK506. Muscle Nerve. 1994;17:528–532. doi: 10.1002/mus.880170510. doi:10.1002/mus.880170510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahlmen J, Andersen O, Hallgren G, et al. Positive effects of tacrolimus in a case of CIDP. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:4194. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)01389-x. doi:10.1016/S0041-1345(98)01389-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Echaniz-Laguna A, Anheim M, Wolf P, et al. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (CIDP) in patients with solid organ transplantation: a clinical, neurophysiological and neuropathological study of 4 cases. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2005;161:1213–1220. doi: 10.1016/s0035-3787(05)85195-1. doi:10.1016/S0035-3787(05)85195-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bodkin CL, Eidelman BH. Sirolimus-induced posterior reversible encephalopathy. Neurology. 2007;68:2039–2040. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000264428.76387.87. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000264428.76387.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molina MG, Diekmann F, Burgos D, et al. Sympathetic dystrophy associated with sirolimus therapy. Transplantation. 2008;85:290–292. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181601230. doi:10.1097/TP.0b013e3181601230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]