Abstract

Background:

Suicide attempts are more common among adolescents than other age groups. Although suicide is considered a worldwide problem, but the related factors, to suicidal behavior are different in various cultures.

Objectives:

The purpose of this study is to identify themes that explain suicide attempt process among adolescents in Iran.

Patients and Methods:

This is a qualitative study carried out based on grounded theory. Key informants were 16 adolescents referred to two hospitals in Shiraz after suicide attempts. Also, 4 family members, a nurse, a psychologist, and a psychiatrist participated in this study. Sampling started with purposive sampling method and continued with theoretical sampling. Data were collected using semi-structured in-depth interviews. Data analysis was carried out using Strauss and Corbin approach and constant comparative method until the point of data saturation.

Results:

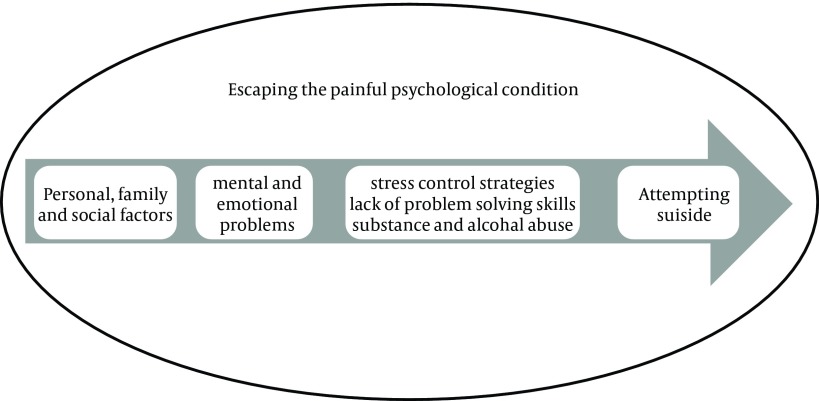

Five main categories, including personal factors and life experiences; family factors, social and educational factors, psychological-emotional problems, and stress control strategies were extracted from the data. The central concept in the data was to escape the painful psychological condition, which was in connection with other concepts describing the process of suicide attempts in adolescents.

Conclusions:

This study identified 5 categories of concepts as main themes that can be used to explain suicidal attempt process among Iranian adolescents.

Keywords: Adolescent, Grounded Theory, Qualitative Research, Suicide Attempt

1. Background

Suicide attempt is a non-fatal act when a person deliberately puts himself or herself at risk of death (1). Research results show that the rate of committed suicides among adolescents in the world is higher than other age groups (2, 3). Suicide is the second leading cause of death in adolescents after accidents (4). Several studies have shown that suicidal behavior in adolescents is a serious public health problem worldwide (5-7). In Iran, a few organizations are engaged in the study of suicide rate. According to Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education statistics, there have been 3170 suicides in Iran in 2012. Drawback of this statistic and other similar statistics (such as report from statistical center of Iran) is the lack of consideration in age variable (8). Nevertheless, In Iran, statistics show that the suicide rate among adolescents has been rising since 1990 (7). According to a study by Haghighat et al. (2013) conducted on children under 18 years old, the prevalence of suicide attempt in Shiraz was 38.50%. In 2005, the prevalence of suicide attempts in this age group in the same city had been estimated as 15.80%. Comparing these figures indicate a rapid increase in the rate of suicide attempts in this age group in Shiraz within a short period (9). Researches show the most common causes of attempted suicide among Iranian adolescents are psychiatric disorders (such as depression), parental conflict, family loss, family history of substance abuse, parental divorce, parent-child friction, sibling friction, low socioeconomic status, romantic issues, and educational issues (2, 7, 10, 11). According to the researches, the most common method used for attempting suicide among Iranian adolescents is drug poisoning (2, 12). Although suicide is considered a worldwide problem, the related factors, beliefs, and attitudes towards suicidal behavior are different in various cultures. Also, the most empirical data on suicide attempts are related to studies in Western countries and the most studies in countries like Iran included simple descriptive studies of suicides and suicide attempts. Therefore developing an idea or a comprehensive theory to investigate this phenomenon in other countries is essential (11, 13, 14). In this regard, qualitative research can help nurses to understand the experience of people who have suicidal attempts and provide an effective nursing care (15, 16). Therefore, a deep understanding of this phenomenon is necessary for suggesting the ways to prevent recurrences and rehabilitation among adolescents who have attempted suicide.

2. Objectives

This study aimed to identify themes based on cultural contexts that explain suicide attempt process among adolescents in Iran.

3. Patients and Methods

This qualitative study was conducted based on grounded theory, which is a methodology suitable for researchers interested to know about basic social and psychological processes that occur over time and to explain variations in a particular behavior (17).

Key informants in this study were 16 adolescents (7 males and 9 females) aged 13 to 19 years, who referred to two hospitals in Shiraz after attempting suicide with drugs. Suicide attempt was approved by the emergency department physician. Four subjects from the adolescents’ parents (3 females and 1 male), as well as 3 members of the medical staff, including a nurse, a psychologist, and a psychiatrist were included in the study for collection of a more comprehensive data.

Initially, the researcher (first author) visited the adolescents in hospitals in order to establish close rapport with them and determine an appropriate time for an interview after being discharged from the hospital. After appointments, interviews were conducted 72 to 96 hours after the participants were discharged from the hospital. The time for interviews was determined based on the subject’s medical condition, ability, and interest.

Exclusion criteria included inability to participate in the study by expression of their experiences for any reason, such as lack of interest, diagnosis with acute psychosis, and severe depression. Sampling started with purposive sampling method with maximum variation (e.g. variation in genders, cultures, and socioeconomic status) and continued with theoretical sampling. Theoretical saturation continued up to 19 interviews i.e. after saturation of all categories until no new relevant meaning unit was found. In order to ensure data saturation, 4 other interviews were conducted with adolescents. Sampling ended after interview with a total of 23 individuals.

The interviewer started the interviews by introducing himself and explaining the purpose and method of the study. Data were collected using semi-structured in-depth interviews. This type of interview is one of the most popular methods of data collection in qualitative researches (18). In this method, the interview begins with a general question and then continues with more specific questions based on the results of the initial interviews and the main themes extracted from interviews (17). Therefore, in this study, interview questions started with a general question (describe a day in your life) and progressively focused on specific issues (such as talking about their feelings before attempting suicide). Therefore, based on the participants’ responses, probing and the following up questions were asked. Form and arrangement of research questions with research progress and in various stages were somewhat different. The researcher was flexible in reaction to different answers provided by the participants. Finally, the interviewer asked the participant to discuss other important issues that were not mentioned during the interview. For convenience of participants, a calm and quiet place was chosen for the interviews. Interviews were conducted from September 2013 to June 2014. Each participant was interviewed one session. The mean duration of the interviews was 50 minutes.

Data collection and analysis were done simultaneously. Regarding analysis, at first, each interview was recorded. After listening to the interviews several times, they were transcribed verbatim and then entered into MAXQDA 10. Data analysis was carried out according to the 3 stage coding approach, including open, axial, and selective coding by Strauss and Corbin (1998) via the constant comparative method (17). After each interview and throughout the data analysis, the researcher wrote theoretical memos that were coded in the process. This contributed to the richness of the data. In the open coding, data were broken down into parts and basic concepts were extracted. Then, meaning units were compared with each other to find similarities and differences and similar concepts were grouped in one category to form more abstract concepts. In the process of interviews, categories gradually became clearer. In the axial coding stage, the analyst spread the categories and linked the sub-categories systematically. In the selective coding, the analyst refined the findings for making decision about the core category. Finally, the findings were integrated to define the core variable and their interrelations.

In the open coding, 1225 codes were extracted. After several revisions, similar items were combined and the number of codes diminished to 16 categories in the axial coding phase. Finally, in the selective coding stage, 16 categories were summarized in a core category and 5 subcategories. At this step, categories and subcategories were systemically linked with the core category during in-depth data collection and constant comparative analysis. The “escaping the painful psychological condition” emerged as the core category during the process of making a link between categories.

To improve the accuracy and rigor of the findings, Lincoln and Guba’s criteria, including credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability were used (18). Researchers tried to increase the credibility of data by keeping prolonged engagement with the process of data collection and analysis, collecting data from two major referral centers for patients who have suicide attempt, writing memos, confirming the accuracy of data analysis by 3 specialists in the field of qualitative research and checking original codes by some participants to compare the findings with the experiences of participants. To increase the dependability and confirmability of data, maximum variation was observed in the sampling. Also, to increase the power of data transferability, adequate description of the data were provided in the study for critical review of findings by other researchers.

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (CT - 92 - 6746). All participants signed the informed consent prepared in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. The parents of participants under 15 years old also signed the informed consent.

4. Results

Average age of adolescents in this study was 16.64 ± 1.60 years old and all of them were single. Five patients had a history of 2 suicide attempts and others once. The main categories of data included personal factors and life experiences; family factors, social and educational factors, psychological-emotional problems, and stress control strategies. The psychological-emotional problems were determined as the main problem and efforts to escape the painful psychological condition was considered as the core variable.

4.1. Personal Factors and Life Experiences

This class includes sub-categories of health, maturity, religious beliefs, and emotional issues such as love and marriage. One participant who had been burned said: "when I see that others walk easily, but I can’t, I get so upset. What’s the use of disabled people?" (Boy, 17 years old). Maturity and the resulting physiological changes can instigate self-injurious behaviors. Describing the day of his suicide attempt, one of the participants said: "For a few days, I felt very bad. I was on my menstruation period. I was very nervous."(Girl, 19 years old). Adolescents’ religious beliefs can affect their suicide attempt. One of the adolescents said: "What is the difference if I die now or 60 years later. Maybe you believe in heaven and hell, but I don’t."(Girl, 18 years). Without a doubt, one of the important experiences of an adolescent is emotional experience. One participant said: "My family didn’t agree with our marriage … I could not tolerate the situation. I had to decide about my prospective wife, this was my right not theirs." (Girl, 18 years).

4.2. Family Factors

This class includes the sub-categories of family structure, communication within the family, family economic characteristics, and family health status. Collapse of the family structure due to mother’s death, divorce, and living with stepparent can make problems for the adolescents. Some quotes from participants are listed below.

"I could not tolerate being away from my mother. I preferred to die."(Boy, 16 years old). "The very next day I got separated from my daughter’s father, she took some pills. Our divorce was a big shock for her." (Woman, 37 years old). Parents’ remarriage after divorce or death of a spouse following which adolescents have to live with stepparents, can make the home intolerable for adolescents. "After my stepmother insulted my mother, I got angry. I could not stand it anymore. I wanted to kill myself." (Boy, 16 years old).

Communication problems between family members can lead to poor emotional relationship between the adolescent and parents and eventually to family conflicts. One participant said: "I disputed with my mom over going out. If their children were important for them, they would give them love and affection not just control their entrance and exit. If my parents had close relationship with me, I could talk about problems with them and I did not commit suicide."(Girl, 19 years old).

One of the most important issues currently facing many families is economic crisis. This crisis can affect adolescents. One participant said: "Our financial situation is really bad. I could not continue this kind of life. Poverty is really bad." (Boy, 17 years old).

Parents’ mental illness and addiction can affect adolescents. One participant said: "After my dad got remarried, my mom got depressed. She doesn’t have a good behavior with me because of her depression. After some disputes with her. I took the pills" (Boy, 17 years old). The most common problem in the families of the participants was father’s addiction that had several consequences. One participant said: "My dad was a drug addict. He did not support us emotionally and financially. My mom had to work. I was tired of living." (Girl, 15 years old).

4.3. Educational and Social Factors

This category contains sub-categories of major and education level, suicidal behavior in others, media influence and professional support. If the educational environment in the community is in such a condition that puts a lot of pressure on the adolescents, it leads to serious problems for them. One participant said: "When I could not enter the University of Medical Sciences. I wanted to die." (Girl, 19 years old). The psychologist noted: "Entering College and studying at high levels in our country is very important. For example, competition for university entrance exam is difficult and puts much pressure on adolescents who may not be able to handle this situation."

History of suicidal behavior in adolescents as well as the influence of media affect adolescents’ suicide attempts. Some participants said: "My husband had attempted suicide. Now my daughter has taken tablet sand says that she learned it from her dad. Suicide is in our nature." (Woman, 37 years old)."A few days ago I watched a movie in which a girl took pills and eases herself." (Girl, 13 years).

Despite the problems in adolescents, almost none of the adolescents and their families received professional support before attempting suicide. The main reason for not seeking advice was their belief that this advice would not solve their problem. Other reasons included lack of trust to others, the belief in solving problems in the family without the help of others, adolescent’s fear of medication, lack of recognition of the problem by family, lack of awareness, and social stigma of mental illness. Some comments from the participants were as follows: "There is no one who can help me… then why should I seek advice." (Boy, 17 years old). "You just cannot talk about these kinds of stuff to anyone." (Boy, 15 years old). "We did not think we need to refer to anyone to solve the problem, we thought we could solve it ourselves." (Woman, 37 years old)."I was afraid of going to the doctor because I had heard they just prescribe medicine." (Boy, 19 years old). The psychiatrist said: "Some of the adolescents and their families do not agree that they have a problem; therefore, they do not seek advice." The psychologist said: "When I talk with families, they say they did not know their children had problems." A nurse said: "Sometimes when we recommend them to visit a psychiatrists, they get frustrated, because they think they are being labeled as a mentally ill person."

4.4. Psychological - Emotional Problems

After the adolescents were faced with problems related to the previous step, they experienced mental and emotional problems such as depression, anxiety, a sense of hopelessness, feelings of worthlessness, feeling guilty, anger or resentment towards themselves. Some quotes from the participants are as follows: "When my mother died, I got depressed." (Boy, 16 years old). "I failed in my love. I felt a sense of hopelessness … I did not account my life of any value."(Boy, 19 years old). "Every time I disputed with my mom, she said: "you are nothing" (Girl, 18 years old)."After a dispute with my mom, she wept. I felt guilty." (Girl, 15 years old). "I was very angry because my mom quarreled with me."(Girl, 13 years old)."After I broke up with my boyfriend, he did not answer my calls, and I was disgusted with myself."(Girl, 17 years old).

4.5. Stress Control Strategies

After adolescents’ emotional reaction to problems they encountered, in the next phase, they tried to reduce their stress levels. Many of them used ineffective strategies such as taking a variety of drugs, smoking, and consuming alcohol to reduce their stress. Some of the statements made by participants are as follows:

"I drank in order to handle the problem of failure in love." (Boy, 16 years old). "I used marijuana to get away from the family atmosphere and problems." (Girl, 18 years old)."Every time I reminded of my love, I felt bad. I took tramadol and then smoked …"(Boy, 18 years old).

Finally, the adolescents thought that suicide was the only way to escape the stress, because they did not have problem solving skills. Some remarks by participants in this regard are as follows:

"I did not find any solution. I thought it was better to kill myself." (Boy, 15 years). "I did not know what I had to do. I took some pills in my hand and I ate them all."(Girl, 13 years). "Whatever thoughts came to my mind, suicide overcame them." (Girl, 15 years).

In general, when adolescents experience problems regarding personal, family and social issues, they respond with some emotional reactions. Then, they try to reduce their stress. Finally, after their struggle is not effective for reducing stress, they attempt suicide as the only way to escape the stresses. Thus investigating the relationships between the obtained concepts show that the core concept is the attempt to escape the painful psychological condition that is in connection with other concepts (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Process of Suicide Attempt Among Adolescents.

5. Discussion

In this study, 5 categories of concepts identified as main themes used to explain suicidal attempt process among Iranian adolescents. Some evidence that supports these main themes are discussed here.

Regarding personal factors affecting suicide attempts, research has shown that there is a relationship between history of suicide attempts and physical disabilities in adolescents. Therefore, adolescents with physical disabilities or long term health problems are more likely to commit suicide attempt compared to other adolescents (19). The hormonal changes of puberty in adolescents (especially girls) can influence adolescents’ behaviors. Evidence shows a significant relationship between suicide attempt among girls and the start of their menstruation periods (20, 21). When a person is confronted with life stresses, religious beliefs are a haven for relaxation. Thus, faith is a strong protective factor against suicide attempt (22, 23). In this study, lack of this protective factor was felt among the participants. Of various experiences of adolescents, their relationship with the opposite sex and the related emotional issues such as love crash are considered among the most important life experiences. If adolescents fail in their emotional relationships with the opposite sex or their family prevent their marriage to their favorite persons, they may be attracted towards attempting suicide (10, 24).

Regarding family factors affecting suicide attempt, several studies show that family problems such as emotional distance between adolescents and parents, poor communication and conflicts between adolescents and parents, unstable family structure due to parental death or divorce, stepparents, a positive history of parental mental illness, and problems such as family poverty and parental drug and alcohol addiction are the most important factors driving adolescent towards suicide attempts (10, 11, 24-29).

Regarding social factors contributing to suicide attempts, studies show that academic failure, history of suicidal behavior among adolescents’ close relatives and family as well as exposure to suicide scenes in films are social factors associated with suicide in adolescents (10, 30-32). According to evidence, receiving professional support has an important role in the prevention of suicide attempt (33, 34). However, 3.4% of those who committed suicide did not get any special psychological care before death (35). There is little information regarding why only a few seek professional help in times of crisis. However, research has shown that personal features such as help-resisters by nature, sufferers, attempts to solve the problem without the help of others, adolescent’s fear of medication, lack of recognition of the problem by family, lack of awareness, and social stigma of mental illness are reasons why individuals and families do not seek professional help in times of trouble (34, 36).

The results of studies show that when adolescents face problems such as emotional breakdown, conflicts with parents or death of close relatives, they experience excitement, anger, sadness, a sense of hopelessness, and guilt. When adolescents lose the ability to deal with the problem due to ineffective coping mechanisms such as escaping from home, substance and alcohol abuse, they attempt suicide. The results of these studies are consistent with the results of our present study (29, 37). In the present study, we describe the correlation between the extracted themes and the participants’ experiences about attempting suicide as a process. According to the process, professionals in this field can help their clients at 3 levels.

At the first level, informing adolescent, their families, and the community particularly schools about the risk factors for suicidal behavior and teaching stress management strategies in times of crisis like problem solving skills training can help prevent the problem. At the second level, providing specialized support systems for these individuals and treatment of adolescents’ problems in the early stages of stress exposure can prevent emotional problems experienced by the adolescents. At the third level, given that history of suicide attempt increases its likelihood, monitoring these people and providing specialized services to them after hospital discharge can help prevent their suicide attempts in future. Then, these 5 main theme categories and related subthemes can have practical benefits in understanding and preventing suicidal attempts in Iranian adolescents.

Difficulty in data collection due to social stigma toward suicide, selection of participants only from hospital admitted cases, and sampling strategy were the limitations of this study. We need quantitative studies to examine these results and generalize them to Iranian adolescent population.

Acknowledgments

The researchers would like to thank all research participants of Namazi and Ali Asghar hospitals who have contributed to the study. The authors would also like to thank the center for development of clinical research of Namazi hospital for cooperation in this study.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions:Mohammad Rafi Bazrafshan developed the study design, conducted the interviews and analysis, ensured trustworthiness, and drafted the manuscript. Farkhondeh Sharif as the supervisor participated in the study design, supervised the codes and data analysis process, and revised the manuscripts. Zahra Molazem and Arash Mani as research consultants participated in the study and advised during the study.

Funding/Support:The present article was extracted from the thesis written by Mohammad Rafi Bazrafshan and was financially supported by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences (Grant No. 92 - 6746).

References

- 1.De Leo D, Burgis S, Bertolote JM, Kerkhof AJ, Bille-Brahe U. Definitions of suicidal behavior: lessons learned from the WHo/EURO multicentre Study. Crisis. 2006;27(1):4–15. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.27.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pajoumand A, Talaie H, Mahdavinejad A, Birang S, Zarei M, Mehregan FF, et al. Suicide epidemiology and characteristics among young Iranians at poison ward, Loghman-Hakim Hospital (1997-2007). Arch Iran Med. 2012;15(4):210–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greydanus DE, Shek D. Deliberate self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Keio J Med. 2009;58(3):144–51. doi: 10.2302/kjm.58.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kostenuik M, Ratnapalan M. Approach to adolescent suicide prevention. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(8):755–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu X, Tein JY, Zhao Z, Sandler IN. Suicidality and correlates among rural adolescents of China. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37(6):443–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez AH, Caldera T, Kullgren G, Renberg ES. Suicidal expressions among young people in Nicaragua: a community-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41(9):692–7. doi: 10.1007/s00127-006-0083-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohammadkhani P, Mohammadi MR, Delavar A, Khushabi KS, Rezaei Dogaheh E, Azadmehr H. Predisposing and Precipitating Risk Factors for Suicide Ideations and Suicide Attempts in Young and Adolescent Girls. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2006;20(3):123–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rezaeian M. Comparing the Statistics of Iranian Ministry of Health with Data of Iranian Statistical Center Regarding Recorded Suicidal Cases in Iran. Health System Res. 2012;8(7):1190–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haghighat M, Moravej H, Moatamedi M. Epidemiology of pediatric acute poisoning in southern Iran: a hospital-based study. Bull Emergen Trauma. 2013;1(1 JAN):28–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keyvanara M, Haghshenas A. Sociocultural contexts of attempting suicide among Iranian youth: a qualitative study. East Mediterr Health J. 2011;17(6):529–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mostafazadeh B, Mesri M, Farzaneh Sheikhahmad E. Assessment the role of effective variables in repeated suicidal attempts. Pejouhesh. 2010;34(2):111–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shirazi HR, Hosseini M, Zoladl M, Malekzadeh M, Momeninejad M, Noorian K, et al. Suicide in the Islamic Republic of Iran: an integrated analysis from 1981 to 2007. East Mediterr Health J. 2012;18(6):607–13. doi: 10.26719/2012.18.6.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lester D. Suicide and islam. Arch Suicide Res. 2006;10(1):77–97. doi: 10.1080/13811110500318489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldston DB, Molock SD, Whitbeck LB, Murakami JL, Zayas LH, Hall GC. Cultural considerations in adolescent suicide prevention and psychosocial treatment. Am Psychol. 2008;63(1):14–31. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lakeman R. What can qualitative research tell us about helping a person who is suicidal? Nurs Times. 2010;106(33):23–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larsson P, Nilsson S, Runeson B, Gustafsson B. Psychiatric nursing care of suicidal patients described by the Sympathy-Acceptance-Understanding-Competence model for confirming nursing. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2007;21(4):222–32. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2007.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Polit-O'Hara D, Beck CT. Essentials of Nursing Research: Methods, Appraisal, and Utilization. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Speziale HS, Streubert HJ, Carpenter DR. Qualitative Research in Nursing: Advancing the Humanistic Imperative. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Everett Jones S, Lollar DJ. Relationship between physical disabilities or long-term health problems and health risk behaviors or conditions among US high school students. J Sch Health. 2008;78(5):252–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00297.x. quiz 298-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rabbani A, Mahmoudi-Gharaei J, Mohammadi MR, Motlagh ME, Mohammad K, Ardalan G, et al. Mental health problems of Iranian female adolescents and its association with pubertal development: a nationwide study. Acta Med Iran. 2012;50(3):169–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sein Anand J, Chodorowski Z, Ciechanowicz R, Wisniewski M, Pankiewicz P. The relationship between suicidal attempts and menstrual cycle in women. Przegl Lek. 2005;62(6):431–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhugra D. Commentary: Religion, religious attitudes and suicide. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(6):1496–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sisask M, Varnik A, Kolves K, Bertolote JM, Bolhari J, Botega NJ, et al. Is religiosity a protective factor against attempted suicide: a cross-cultural case-control study. Arch Suicide Res. 2010;14(1):44–55. doi: 10.1080/13811110903479052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keyvanara M, Haghshenas A. The sociocultural contexts of attempting suicide among women in Iran. Health Care Women Int. 2010;31(9):771–83. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2010.487962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stenager K, Qin P. Individual and parental psychiatric history and risk for suicide among adolescents and young adults in Denmark: a population-based study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2008;43(11):920–6. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwok SY, Shek DT. Hopelessness, parent-adolescent communication, and suicidal ideation among Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2010;40(3):224–33. doi: 10.1521/suli.2010.40.3.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seghatoleslam T, Habi H, Rashid RA, Mosavi N, Asmaee S, Naseri A. Is suicide predictable? Iran J Public Health. 2012;41(5):39–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christoffersen MN, Soothill K. The long-term consequences of parental alcohol abuse: a cohort study of children in Denmark. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003;25(2):107–16. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herrera A, Dahlblom K, Dahlgren L, Kullgren G. Pathways to suicidal behaviour among adolescent girls in Nicaragua. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(4):805–14. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nazarzadeh M, Bidel Z, Ayubi E, Asadollahi K, Carson KV, Sayehmiri K. Determination of the social related factors of suicide in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ali MM, Dwyer DS, Rizzo JA. The social contagion effect of suicidal behavior in adolescents: does it really exist? J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2011;14(1):3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shain BN, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on A. Suicide and suicide attempts in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2007;120(3):669–76. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suominen K, Isometsa E, Martunnen M, Ostamo A, Lonnqvist J. Health care contacts before and after attempted suicide among adolescent and young adult versus older suicide attempters. Psychol Med. 2004;34(2):313–21. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Owens C, Lambert H, Donovan J, Lloyd KR. A qualitative study of help seeking and primary care consultation prior to suicide. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(516):503–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Owens C, Booth N, Briscoe M, Lawrence C, Lloyd K. Suicide outside the care of mental health services: a case-controlled psychological autopsy study. Crisis. 2003;24(3):113–21. doi: 10.1027//0227-5910.24.3.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ebrahimi H, Namdar H, Vahidi M. Mental illness stigma among nurses in psychiatric wards of teaching hospitals in the north-west of Iran. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2012;17(7):534–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Obando Medina CM, Dahlblom K, Dahlgren L, Herrera A, Kullgren G. I keep my problems to myself: pathways to suicide attempts in Nicaraguan young men. J Suicidology. 2011;2(1):17–28. [Google Scholar]