Abstract

Height is a marker for health, cognitive ability and economic productivity. Recent research on the determinants of height suggests that postneonatal mortality predicts height because it is a measure of the early life disease environment to which a cohort is exposed. This article advances the literature on the determinants of height by examining the role of early life mortality, including neonatal mortality, in India, a large developing country with a very short population. It uses state level variation in neonatal mortality, postneonatal mortality, and pre-adult mortality to predict the heights of adults born between 1970 and 1983, and neonatal and postneonatal mortality to predict the heights of children born between 1995 and 2005. In contrast to what is found in the literature on developed countries, I find that state level variation in neonatal mortality is a strong predictor of adult and child heights. This may be due to state level variation in, and overall poor levels of, pre-natal nutrition in India.

Keywords: height, India, neonatal mortality, postneonatal mortality, maternal nutrition JEL classifications, I1, J1

1 Introduction

Economists have often used height as a measure of human development. Recent research has documented important relationships between height and survival, height and cognitive achievement, and height and productivity.1 The importance of height as a measure of population health and well-being has led to the question: what determines height?

Several studies have used data from Europe to establish correlations between height and early life conditions, as captured by mortality levels in infancy [55, 20, 16, 34, 35]. Postneonatal mortality (PNM), the number of infants per 1000 live births who die between the first and the twelfth months of life, emerges as a strong predictor of height. In these studies, postneonatal mortality is understood to proxy for the disease environment to which infants are exposed. Infants exposed to more disease early in life experience poor growth, leaving them stunted. In [16], neonatal mortality (NNM), which was largely determined by the availability of advanced medical care for neonates, had no correlation with adult heights in European and American cohorts born from 1950-1980, controlling for other factors.

As in developed countries, height in developing countries is determined in large part by early life conditions, especially from conception to two years of age, but these conditions tend to be more varied, and more damaging than in developed countries. Also as in developed countries, the disease environment is likely an important determinant of height, but other factors, such as economic well-being and pre-natal nutrition may play a more important role in developing countries than in developed ones.

This paper examines correlates of height in India, a large developing country with one of the shortest populations in the world, and with significant differences in health outcomes across states [24, 26]. It finds that state level variation in mortality levels from a cohort's infancy predict both the heights of Indian adults born between 1970 and 1983, and the heights of Indian children born between 1995 and 2005. Consistent with prior literature on mortality and the disease environment, I find that state level variation in pre-adult mortality and postneonatal mortality correlate with adult height and child height, respectively. A novel finding of the paper is that, in contrast to in developed countries, neonatal mortality, or mortality between birth and one month of life, is a robust predictor of height in India. This is true both for adults born between 1970 and 1983, and for children born between 1995 and 2005.

The relationship between state level neonatal mortality and height is robust to controlling for postneonatal mortality, which proxies for the disease environment, as well as economic circumstances, measured by state domestic product, in the case of the adults, and household asset wealth, in the case of the children. Unlike in literature on the correlates of height from developed countries, but consistent with prior research on height in developing countries, I find that these measures of economic well-being indeed predict height [60]. Regressions of children's height on early life mortality rates also control for mother's height, suggesting that there is not a spurious correlation between mortality in the state where a baby is born and her genetic height potential.

The finding that state level variation in neonatal mortality predicts Indians’ heights raises the question: for what early life conditions that shape height does neonatal mortality proxy? I review the literature and existing cause of death data and propose that low birth weight, caused by poor pre-natal nutrition, could be driving the correlation between neonatal mortality and height. Vital statistics data suggest that low birth weight has long been, and continues to be, a leading cause of neonatal mortality in India. Indeed, [64] estimate that about a third of infants in India are born at a low birth weight, and that India is home to forty percent of the world's low birth weight babies. Although no representative state or national-level data on birth weight exist, the National Family Health Survey data reveal important differences in women's nutrition across Indian states.

These findings are important for researchers seeking to understand why, despite its high rates of economic growth, India continues to have one of the shortest populations in the world. Although Indians’ heights are certainly determined by many factors,2 these findings suggest that continuing neglect of women's health, and in particular pre-natal nutrition, will have continuing consequences for heights in India, and for all of the health and human development indicators that height reflects.

The paper proceeds as follow: section 2 provides contextual information on the early life determinants of height in developed and developing countries, as well as on causes of early life mortality in India. Section 3 presents the data sources and modeling strategy. Section 4 presents the results of three analyses: the first regresses the heights of adult cohorts born between 1970 and 1983 in different states of India on neonatal and postneonatal mortality rates in their years of birth; the second regresses the heights of these adults on pre-adult mortality rates in their year of birth; and the third regresses the height-for-age z-scores of individual children from two rounds of India's Demographic and Health Survey on state-survey round level measures of neonatal and postneonatal mortality. Section 5 discusses the results, as well as the hypothesis that variation in neonatal mortality proxies for state level variation in maternal net nutrition. Section 6 concludes.

2 Context

2.1 Early life determinants of height in developed countries

In Europe, the relationships between height and the early life environment have been examined in the context of select groups, as well as at the population level. [55] document a relationship between the adult heights of men who were conscripted in European armies and postneonatal mortality in the year of birth. [16] provide evidence for a similar relationship in the general populations of European countries and the United States for cohorts born between 1950 and 1980. They show that the relationship between adult height and postneonatal mortality is robust to a variety of controls, including neonatal mortality, log of GDP in the cohort's year and country of birth, and country and year fixed effects. [34] finds a robust correlation between the heights of school children born between 1910 and 1950 in Britain and the infant mortality rates that prevailed when those children were between two and four years old.

All three of these papers posit that the mechanism linking height and early life mortality is the disease environment in early childhood. In [16], postneonatal deaths from pneumonia and diarrhea, diseases which are known to lead to stunting in childhood, correlate with adult heights, though death rates from pneumonia predict heights more strongly. None of the papers finds evidence of an effect of neonatal mortality on adult heights.

In these contexts, one would not expect adult height to be strongly influenced by factors determining neonatal mortality. Whereas in developing countries, temporal or regional differences in neonatal mortality might be due to variation in maternal nutritional deprivation during pregnancy, in developed countries, differences in the availability of life saving technology for premature infants would play a far more important role. Research on the relationship between maternal nutrition and infant outcomes in developed countries tends to focus on overweight and obese women, rather than on undernourished women. [16] test for but do not find evidence of an effect of income on adult heights in Europe. The authors remind readers that their results do not rule out income or nutrition related constraints on adult heights for Western cohorts born pre-1950, nor do they rule out such a constraint on adult height in developing countries.

2.2 Early life determinants of height in developing countries

[56] posits that the determinants of variation in height are different in developed and developing countries, and in particular, that compared to developed country settings, environmental variation (as opposed to genetic variation) in height is relatively large. This is because environmental insults to childhood growth are more severe in developing countries.3

Many factors determine heights in developing country and pre-industrial settings, and higher levels of development do not always lead to growth in physical stature [41, 42]. However, at low levels of development, additional income may influence height through increasing calorie intake or the quality of the diet. [29] discusses relationships between income, calorie availability and body size. In particular, Fogel proposes a “technophysio evolution” of body size corresponding with calorie availability, which in many contexts increases when income increases. The importance of shocks to income and nutrition as determinants of early life height and health have also been demonstrated in developing country settings [47, 10].

Empirical evidence suggests that the early life disease environment influences height in impoverished settings. [2] find that with the exception of sub-Saharan Africa, where the authors hypothesize that improvements in infant mortality have not been importantly due to reductions in morbidity, changes in adult heights correlate with changes in infant mortality rates in developing regions. Using data from three European populations in the 1800s, [20] find relationships between adult height and pre-adult mortality4 measured when a cohort was a year old. Additionally, [59] suggests that sanitation coverage, a measure of the fecal pathogens to which a child is exposed, is a strong predictor of children's heights in modern developing countries.

Finally, pre-natal conditions may also contribute to stunting in situations of scarcity. There is substantial evidence that maternal nutrition promotes birth weight in developing countries [46], and that birth weight is an important predictor of height [14, 1]. A longitudinal study from Brazil finds that low birth weight is correlated with low pre-pregnancy weight [7]. [44] reviews the literature on birth weight, and concludes that, in addition to low pre-pregnancy weight, low weight gain during pregnancy additionally correlates with low birth weights in developing countries. [37] discusses this relationship in the context of food supplements in pregnancy, which increase birth weights where women are undernourished.

[1] establishes links between birth size and adult height in a sample from the Philippines. [14] show that two causes of low birth weight–intrauterine growth retardation and prematurity–are both associated with low adult heights, though the relationship is stronger for intrauterine growth retarded infants than for premature infants.5 [9] show that differences in birth weight between identical twins predicts differences in height. Finally, [45] present experimental evidence from Indonesia that supplementation during pregnancy improves postnatal growth–that is, growth from age zero to age five. These findings are particularly important for India, where discrimination against women of child-bearing age, even in food consumption, is well documented [39, 21, 51].

2.3 Causes of early life mortality in India

Cause of death data help identify those early life conditions that both kill children and stunt their growth, and those causes of death that are unlikely to also be, or to proxy for, major determinants of height. What are the leading causes of early life mortality in India?

Table 1 summarizes the results of the Million Deaths study, a national study of cause of death that was conducted in 2005 [48]. Prematurity/low birth weight was the second leading cause of death at all ages and the leading cause of neonatal mortality, responsible for over a third of neonatal deaths. Neonatal infection was the second leading cause of neonatal death; according to [48], neonatal infection comprises neonatal pneumonia, septicemia and meningitis. Birth asphxia and trauma are the third cause of neonatal death. Together these three causes account for about 80% of neonatal death. Table 1 also shows cause of death for children between 1 and 59 months of life. The leading causes of child mortality are pneumonia and diarrheal diseases. A number of other infectious diseases comprise a large fraction of the remaining child mortality.

Table 1.

Causes of early life mortality in India from the 2010 Million Deaths Study

| mortality from 0-1 months | |

|---|---|

| cause of death | mortality rate per thousand live births (all India 2005) |

| prematurity and low birth weight | 12.0 |

| neonatal infections | 9.9 |

| birth asphyxia and birth trauma | 7.0 |

| other non-communicable diseases | 1.8 |

| congenital anomalies | 1.2 |

| tetanus | 1.2 |

| injuries | 0.2 |

| other causes | 2.4 |

| all causes | 36.9 |

| mortality from 1-59 months | |

|---|---|

| cause of death | mortality rate per thousand live births (all India 2005) |

| pneumonia | 13.5 |

| diarrhoeal diseases | 11.1 |

| measles | 3.3 |

| other non-communicable diseases | 3.2 |

| injuries | 2.9 |

| malaria | 2.0 |

| meningitis/encephalitis | 1.9 |

| nutritional diseases | 1.5 |

| acute bacterial sepsis and severe infections | 1.4 |

| other infectious diseases | 1.2 |

| other causes | 6.9 |

| all causes | 48.9 |

Source: Million Death Collaborators (2010). Causes of neonatal and child mortality in India: A nationally representative mortality survey. The Lancet 376, 1853-1860.

Among these causes of early life mortality, which reflect conditions that would also affect height? As outlined in section 2.2, there is clear evidence that low birth weight is importantly caused by poor pre-natal nutrition, which is prevalent in India, and which also affects child and adult height. We would not expect birth asphyxia and trauma to cause stunting later in life. The extent to which the neonatal infections identified by the Million Deaths Study as important causes of death affect height is unclear. These infections are likely to be fast-acting, and are typically acquired before or during birth, or shortly thereafter [27].6 While these early infections may have consequences for the heights of children who survive them, there is little evidence to suggest that they sap energy for growth in the way that postneonatal infections like respiratory and gastrointestinal infections do. In contrast, there is clear evidence that both respiratory and gastrointestinal infections impact height. [65] and [16] find evidence that respiratory infections such as pneumonia stunt height, and [19] discuss the role of diarrheal disease in stunting.7

Because neonatal mortality is a particular focus on this paper, it would be useful to know whether the major causes of neonatal death in the 1970s and early 1980s were the same as in 2005, when the Million Deaths study was conducted. This is a difficult question to answer precisely due to lack of high quality cause of death data from this period. However, a cause of death study conducted by the Office of the Registrar General (ORG) in major Indian states in 1978 found that tetanus was the most common cause of neonatal mortality [33]. In contrast, the Million Deaths Study of 2010 found a death rate from neonatal tetanus of only 1.2 per 1000 live births. This suggests that the importance of neonatal tetanus has declined dramatically between the time in which the adults studied here were infants, and when the children studied here were infants.

Despite the importance of neonatal tetanus in determining the mortality rates for the adult cohorts I study, it is unlikely to have been an important cause of their stunting. In the 1970s and 80s, fatality from neonatal tetanus would have been extremely high. [63] reports that fatality rates from untreated neonatal tetanus can be as high as 100%, and [57] report on a study from Côte d'Ivoire estimates a fatality rate from neonatal tetanus of 90%. If nearly all children who suffered from tetanus died of it, it is unlikely to have been a major cause of stunting.

The 1978 ORG study suggests that low birth weight/prematurity was the second most important cause of neonatal death during the period in which the adults studied in this paper were infants [33].8 This cause of death likely reflects conditions of poor pre-natal nutrition that would have also played an important role in determining heights. The correlation between adult height and neonatal mortality that will be discussed in section 4 may reflect statewise variation in pre-natal nutrition when these adults were in utero, a hypothesis which will be discussed further in section 5.

3 Data & modeling approach

3.1 Data sources & descriptive statistics

3.1.1 Adult analyses

Mortality indicators

Mortality indicators from the 1970s and 1980s used for the analysis of adult heights come from the Sample Registration System (SRS), a vital statistics system run by the Office of the Registrar General at the Indian Ministry of Home Affairs. Trained SRS enumerators register vital events in sample localities in order to estimate demographic rates at the state and national levels. The SRS data cover the 17 major Indian states;9 data are available beginning in 1970. Data from the small northeastern states are missing from the SRS.10 Bihar, Jammu & Kashmir and Punjab also have missing data: data from Bihar are missing from 1970-1980; data from Jammu & Kashmir are missing from 1970-1971; and data from Punjab are missing from 1970. [32] and [12] provide detailed information about the SRS.

Height

Data on adult height are taken from two nationally representative surveys, the National Family Health Survey 2 (NFHS 2), which collected data on the heights of adult women in 1998-1999, and the National Family Health Survey 3 (NFHS 3), which collected data on the heights of adult men and women in 2004-2005. The analysis of adult heights includes only individuals aged 22 and older at the time that their heights were measured. The age of 22 was chosen because [24] finds that men and women in India do not reach their adult heights until their early 20s. Since the SRS began measuring mortality in 1970, I have included in the sample women measured in the NFHS 2 and born between 1970 and 1977, as well as men and women measured in NFHS 3 and born between 1970 and 1983.

When matching the heights of individuals measured in NFHS 3 to the SRS data, it is necessary to account for the fact that some state boundaries changed between 1970 and 2005. NFHS 3 height from both Uttarkhand and Uttar Pradesh are matched with SRS data for Uttar Pradesh. Similarly, Bihar and Jharkhand, and for Chattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh.

Control variables

For the analysis using adult heights, controls for state level income from the 1970s and 1980s come from the Economic & Political Weekly (EPW) Research Foundation, which produced an annual series of net domestic product by state, at 1970 prices, for the period from 1970-1983. [28] explains that net state domestic product is “the totality of commodities and services produced during a given period of time within the geographical boundary of the state in monetary terms counted without duplication” (175). State net domestic product per capita does not include, for example, remittance income from migrants working outside the state. The EPW series has complete information on Indian states during the time period of interest.

The analyses using data on the heights of adults additionally control for whether the state is in the north, as well as for survey round and year of birth.

Summary statistics

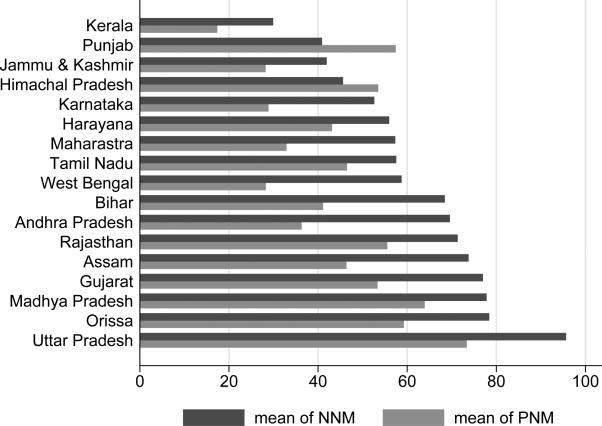

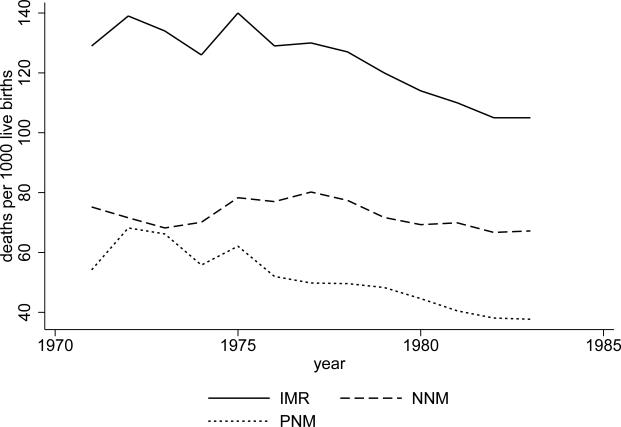

Figure 1 presents summary statistics that reveal large variation at the state level in early life mortality rates during the period from 1970 to 1983, but figure 2 shows that there was much less variation in mortality rates over time during this period. Figure 1 shows the average neonatal and postneonatal mortality rates in each state from the period of 1970-1983, and figure 2 shows the national time trends for neonatal and postneonatal mortality. National neonatal mortality changed very little, from 75 deaths per thousand to about 70. Decline in postneonatal mortality, from about 65 to about 38, was responsible for much of the national decline in infant mortality.11

Figure 1. State-wise average mortality rates from 1970-1983.

Data are from the Sample Registration System. State-wise means of neonatal mortality (NNM) and postneonatal mortality (PNM) are shown for the period from 1970-1983 for the states included in this analysis. A few states are missing values for 1970 and 1971 and Bihar and West Bengal only have PNMs for 1981-1983.

Figure 2. National mortality rates from 1970-1983.

Data are from the Sample Registration System. National time trends are shown for neonatal mortality (NNM), postneonatal mortality (PNM), and infant mortality (IMR), for the period from 1970-1983 for the states included in this analysis. A few states are missing values for 1970 and 1971 and Bihar and West Bengal only have PNMs for 1981-1983.

3.1.2 Child analyses

Mortality indicators

In the child level analysis, I compute neonatal and postneonatal mortality from the National Family Health Surveys (NFHS) at the state-survey round levels. I use children born in the three years before the survey in order to compute these measures. A child, whether dead or alive at the time of the survey, is included in the computation of neonatal mortality only if at least a month has passed since his birth. Likewise, a child is used in the computation of postneonatal mortality only if at least a year has passed since his birth. I scale the fraction of children who died by 1000 to allow for a simple interpretation of the coefficients.

Height

Height-for-age z-scores of children under three years of age are the dependent variable. z-scores provide a measure of the heights of children relative to a healthy population. These scores were computed based on the WHO 2006 growth reference standards [22].12 For children in NFHS 3, scores are provided in the published data; for children in the NFHS 2, scores were computed based on child sex, age and height in centimeters using WHO Anthro software [70].

Control variables

All specifications include a vector of controls for the age-in-months of the child. Controls for economic well-being include a vector of dummy variables for ownership of household assets, including whether or not the child's household owns a radio, a TV, a fridge, a bicycle, a motorcycle, a car, whether the household has electricity, and the household's drinking water source. A control for mother's height, a measure of the child's genetic potential, is also included.

Summary statistics

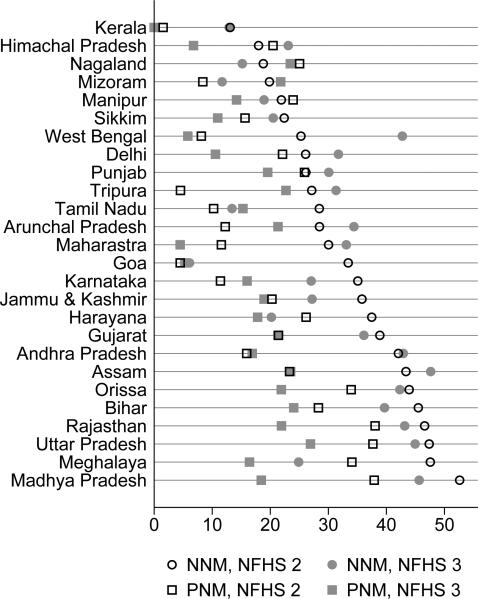

Figure 3 presents summary statistics of the state level neonatal and postneonatal mortality rates used in the child level analysis. The Indian states shown in figure 3 are ordered by their neonatal mortality rates form the NFHS 2, which range from approximately 13 in Kerala, to over 50 in Madhya Pradesh. When using the NFHS 3 data for this figure, and for all the following analyses, I merge data for the states that split between 1998 and 2005 into the state that existed in 1998. Therefore, Jharkhand and Bihar are represented by Bihar, Chattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh are represented by Madhya Pradesh, and Uttarkhand and Uttar Pradesh are represented by Uttar Pradesh.

Figure 3. Early life mortality measures in the NFHS 2 and the NFHS 3.

Neonatal and postneonatal morality are given at the state-survey round level, based on the fraction of children born in the three years before the survey who died. A child, whether dead or alive at the time of the survey, is used in the computation of neonatal mortality only if at least a month has passed since his birth. Likewise, a child is used in the computation of postneonatal mortality only if at least a year has passed since his birth. The fraction of children who died is scaled by 1000.

3.2 Modeling approach

3.2.1 Stunting and selection

Research that correlates early childhood mortality rates with height often interprets mortality rates as a measure of the force or burden of disease in a population. However, the effect of disease burdens in childhood on heights may not always be monotonic. [53], [16] and [34] recognize that high disease burdens could cause both selection and stunting of survivors. Where there is selection, healthier (taller) members of a cohort survive childhood; where there is stunting, adult heights are lower than their genetic potential because energy is spent fighting disease rather than growing during formative years. Thus selection and stunting could produce offsetting effects on height. [16] develop a model of the joint effects of selection and stunting on population heights. They predict that, at a given high level of infant mortality, the selection effect may dominate stunting such that the adults of a cohort which experienced a very high disease burden in infancy may be taller than a cohort which experienced a slightly lower disease burden. Although they derive this result theoretically, clear evidence for the existence of a “turning point” is lacking.13

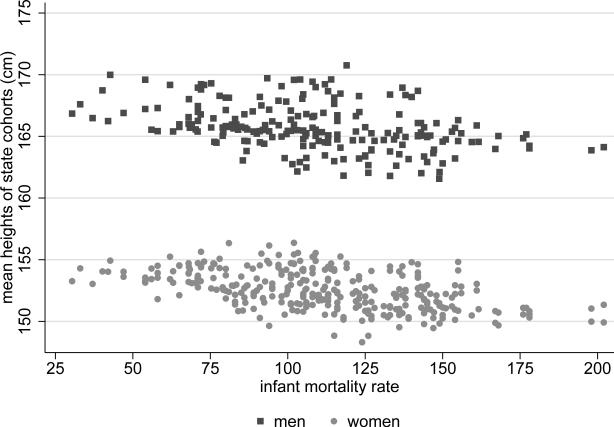

In the Indian data, however, there is no evidence of a “selection effect.” Figure 4 shows a scatter plot (separately for men and women) of the relationship between the infant mortality rate to which a state cohort born between 1970 and 1983 was exposed in its year of birth, and the average height of the adults in that state cohort. Although there is a negative relationship between infant mortality and height, figure 4 shows no visible reversal, or flattening out, of the stunting effect at high levels of infant mortality. If a quadratic function is nonetheless fitted to the data in figure 4, the coefficient on the quadratic term, though positive, is not statistically significant. The turning points would be at 262 for men and 212 for women. These numbers are not beyond the realm of human experience, but they are far extrapolations of the relationships in these data. Finally, [3] assess the magnitude of the bias in Indian children's heights that might be due to selection, and find that the effect is likely small. Therefore, this paper models the relationships between heights and mortality using only linear terms throughout.

Figure 4. Relationship between adult heights and infant mortality.

Observations are state cohorts born 1970-1983. The slope of a tted line for women is −0.022 and the p-value is <0.001, using homoskedastic standard errors. The slope of the tted line for men is -0.023 and the p-value is <0.001.

3.2.2 Men and women

The heights of Indian men and women should be modeled separately for several reasons. First, sex ratios differ substantially across time and place [11]. Second, it is likely that somewhat different processes determine the heights of men and women. Sex discrimination in the allocation of nutrition and health in early childhood has been well-documented (see [8], [15] and [52]). These differences in early life conditions could lead different determinants of height to be more important for one sex than the other. Indeed, [24] shows that there have been different trends in men's and women's heights in India from the 1960s to 2005: men have grown at about three times the rate of women. Finally, [6] show that compared to children in other developing countries, boys in rural India have an advantage in height relative to girls.

4 Results

4.1 Neonatal mortality, postneonatal mortality & adult height

I use ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to estimate the association between early life mortality and the mean heights of adult cohorts. The variation exploited in this analysis comes primarily from large variation in mortality across states. While other papers that have looked at the relationship between measures of early life conditions and adult height have done so during a period of declining infant mortality, and have found effects of mortality on adult height controlling for year, for region, or both, the meager declines in infant mortality in India during the periods under study mean that the conclusions presented here are based almost entirely on variation in mortality across the states. Thus, the relationships are not robust to including state fixed effects. The relationship between adult height and neonatal mortality is robust to controls for state net domestic product per capita and a fixed effect for being a northern state.

Table 2 presents the results of twelve regressions of similar form. Panel A presents the results for women and panel B presents the results for men. Column 1 shows the results of regressions of height on neonatal mortality, and column 2 regresses adult height on postneonatal mortality. Columns 3 through 6 introduce controls to demonstrate the robustness of the association between adult height and neonatal mortality.

Table 2.

Neonatal, postneonatal mortality & adult height in India (state cohorts)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| height in centimeters | ||||||

| Panel A: women (pooled sample of NFHS 2 & 3) | ||||||

| NNM | −0.046*** (0.008) | −0.047*** (0.008) | −0.036*** (0.009) | −0.037*** (0.008) | −0.036*** (0.008) | |

| p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.002 | p = 0.000 | p = 0.000 | ||

| PNM | −0.017 (0.013) | 0.002 (0.006) | 0.003 (0.008) | −0.000 (0.010) | −0.003 (0.012) | |

| ln(NSDPPC) | 1.826* (0.720) | 1.698* (0.744) | 1.764* (0.803) | |||

| northern state | 0.296 (0.446) | 0.351 (0.460) | ||||

| NFHS 3 | 0.588*** (0.111) | 0.525** (0.139) | 0.603*** (0.101) | 0.541*** (0.117) | 0.524*** (0.123) | 0.583*** (0.117) |

| YOB fixed effect | no | no | no | no | no | yes |

| constant | 155.000*** (0.466) | 153.000*** (0.686) | 155.000*** (0.554) | 142.500*** (4.768) | 143.300*** (4.935) | 142.600*** (5.191) |

| R 2 | 0.369 | 0.083 | 0.370 | 0.455 | 0.460 | 0.483 |

| n (state cohorts) | 322 | 322 | 322 | 322 | 322 | 322 |

|

Panel B: men (NFHS 3 only) | ||||||

| NNM | −0.050*** (0.011) | −0.054*** (0.011) | −0.037** (0.011) | −0.039** (0.011) | −0.039** (0.011) | |

| p = 0.000 | p = 0.001 | p = 0.009 | p = 0.010 | p = 0.007 | ||

| PNM | −0.015 (0.015) | 0.009 (0.009) | 0.012 (0.009) | 0.008 (0.012) | 0.004 (0.013) | |

| ln(NSDPPC) | 2.958** (0.788) | 2.795** (0.834) | 2.784** (0.875) | |||

| northern state | 0.375 (0.541) | 0.480 (0.537) | ||||

| YOB fixed effects | no | no | no | no | no | yes |

| constant | 168.800*** (0.677) | 166.400*** (0.683) | 168.700*** (0.625) | 148.300*** (5.442) | 149.300*** (5.742) | 148.800*** (5.833) |

| R 2 | 0.257 | 0.023 | 0.264 | 0.431 | 0.436 | 0.475 |

| n (state cohorts) | 209 | 209 | 209 | 209 | 209 | 209 |

Notes: OLS regression model. Standard errors are clustered at the state level and shown in parentheses. Due to the small number of clusters (17), I have also computed wild bootstrap t two-sided p-values for neonatal mortality (see [17]); these are listed below clustered standard errors.

† p < 0.1

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001. NNM is neonatal mortality; PNM is postneonatal mortality; YOB fixed effects are year of birth fixed effects; ln(NSDPPC) is the natural log of net state domestic product per capita.

The regression equation which corresponds to column 6 of panel A of table 2 is:

| (1) |

where mean heightrys is the mean height of the cohort of women measured in survey round r, born in year y and residing in state s at the time they were surveyed. Since the NFHS does not have information on the state of birth, all of the specifications assume that the state of residence at the time of the survey is the state of birth. The assumption is likely unproblematic for the analysis; [49] point out that India has very low rates of mobility compared to other developing countries. Though women are more mobile than men due to migration for marriage, cultural and linguistic differences across states make inter-state marriage relatively rare. Moreover, [62] cite a figure from the 2001 census identifying 41 million Indians as inter-state migrants. This is less than 4% of the 2001 population.

NNMys is the neonatal mortality rate in state s in year y, and PNMys is the post-neonatal mortality rate. ln(SDP)ys is the log of the net state domestic product per capita for state s in year y. northys is a dummy variable that controls for possible spurious correlation between neonatal mortality and region.14 [24] finds that in northern states the difference between men's and women's heights is greater than in southern states. αy is a fixed effect for year of birth.

ϕr is a fixed effect for survey round, which is equal to one if the height data for cohort ys was taken from the NFHS 3. [25] have documented a systematic difference in the heights of women between the two rounds of the survey; the same cohorts are about 0.5 centimeters taller when measured in NFHS 3. The fixed effect for survey round is only used in regressions in which the dependent variable is women's heights because men's heights were not measured in NFHS 2.

Standard errors were clustered at the state level. However, due to concern about the small number of clusters (there are 17 states), wild-cluster bootstrap t p-values, as suggested by [17], are additionally shown for the coefficients on NNMys in each of the regressions. These regression results are unweighted, but weighting by the number of observations that were used to calculate the mean of heights does not change any of the main conclusions.

Column 1 of table 2 shows the results of a regression of adult height on neonatal mortality in the year of birth. The coefficient on neonatal mortality is negative and statistically significant. Column 2 of table 2 shows the results of a regression of adult height on postneonatal mortality. The coefficient on postneonatal mortality is negative, but not statistically significant for either men or women. Columns 3-6 of table 2 show regressions that include both neonatal and postneonatal mortality, and controls for income, region, year of birth and survey round. Again, it is neonatal mortality that has a robust and statistically significant association with adult heights.

The magnitudes of the coefficients on neonatal mortality in columns 3-6 are similar for men and women; they are about −0.04. This suggests that a 20 per thousand reduction in neonatal mortality is associated with a 0.8 centimeter difference in the mean heights of state cohorts.

These findings differ from the findings of papers using developed country data on adult heights and early life mortality in two ways. First, this paper finds that neonatal mortality is a strong predictor of adults heights. Second, it finds that net domestic product is a significant predictor of adult height, even controlling for postneonatal mortality. The coefficient on state net domestic product per capita in column 6 suggests that a 10 percent difference in state net domestic product per capita is associated with a 0.17 centimeter difference in average women's heights, and a 0.27 centimeter difference in average men's heights. This suggests that the difference in the rates of change of men's and women's heights in India, documented by [24], might be in part explained by an associate between material resources and men's heights that is different from the association between material resources and women's heights.

The lack of a statistically significant relationship between adult heights and post-neonatal mortality in these data is puzzling, and raises a potential issue of data quality, since it is likely that the early life disease environment likely mattered for determining heights in this context. Therefore, it is probably not appropriate to interpret this lack of relationship as evidence that the disease environment in early life did not affect adult heights in this context. Indeed, [16] have suggested that postneonatal mortality may be an incomplete measure of the disease environment in poor country settings. They suggest using measures of pre-adult mortality, which provide more complete information on the disease environment because they measure mortality between the ages of 0 and 15 in the cohort's year of birth. The following section presents the relationship between pre-adult mortality and adult height. There are indeed statistically significant relationship between pre-adult mortality and adult height.

4.2 Pre-adult mortality & adult height

Table 3 reports the results of OLS regressions of adult heights of state cohorts born in India between 1970 and 1983 on levels of pre-adult mortality to which they were exposed in their first year of life. Each panel of columns 1 and 2 of table 3 presents the results of six regressions. The coefficients reported for each of the nmx in column 1 of panel A are the from regressions of the form:

| (2) |

The coefficients in column 2 are generated using the same procedure, but controls are added for log of net state domestic product per capita, northern region, and year fixed effects. Standard errors, clustered at the state level, are shown in parentheses. Each of the mortality rates has a statistically significant effect on adult heights in both the uncontrolled and the controlled regressions.15

Table 3.

Pre-Adult Mortality & Adult Height in India (state cohorts)

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

columns 1-6: Height in centimeters is dependent variable. For 1 & 2, see notes below. | ||||||

| Panel A: women, pooled sample of NFHS 2 & 3 | ||||||

| 5 m 0 | −0.044*** (0.011) | −0.034† (0.017) | −0.017 (0.016) | −0.013 (0.015) | −0.015 (0.018) | −0.018 (0.019) |

| 5 m 5 | −0.525*** (0.101) | −0.396** (0.123) | −0.295* (0.128) | −0.163 (0.097) | −0.155 (0.109) | −0.199 (0.131) |

| 5 m 10 | −0.890*** (0.210) | −0.637* (0.225) | −0.3451 (0.178) | −0.292 (0.183) | −0.298 (0.186) | −0.347† (0.183) |

| ln(net state domestic product per capita) | ✓ | 1.739† (0.852) | 1.685† (0.896) | 1.609† (0.875) | ||

| northern state | ✓ | 0.132 (0.483) | 0.213 (0.468) | |||

| indicator for NFHS 3 | ✓ | ✓ | 0.340* (0.121) | 0.361** (0.122) | 0.356* (0.123) | 0.583*** (0.117) |

| year fixed effects | no | yes | no | no | no | yes |

| constant | ✓ | ✓ | 154.9*** (0.585) | 142.8*** (5.740) | 143.2*** (6.035) | 143.7*** (5.778) |

| R 2 | - | - | 0.330 | 0.400 | 0.400 | 0.450 |

| n (state cohorts) | 321 | 321 | 321 | 321 | 321 | 321 |

| p value of F test | ||||||

| for joint significance | p = 0.000 | p = 0.011 | p = 0.012 | p = 0.002 | ||

| of 5m0, 5m5, 5m10 | ||||||

|

Panel B: men, NFHS 3 | ||||||

| 0 m 5 | −0.042** (0.0126) | −0.024 (0.021) | −0.007 (−0.490) | −0.000 (−0.010) | −0.003 (−0.170) | −0.007 (−0.470) |

| 5 m 5 | −0.536** (0.156) | −0.3301 (0.175) | −0.344† (−1.750) | −0.103 (−0.810) | −0.093 (−0.700) | −0.153 (−1.090) |

| 5 m 10 | −0.950** (0.284) | −0.632* (0.264) | −0.403 (−1.620) | −0.327 (−1.490) | −0.333 (−1.480) | −0.432† (−2.030) |

| ln(net state domestic product per capita) | ✓ | 3.132** (3.270) | 3.066** (3.020) | 2.873** (3.010) | ||

| northern state | ✓ | 0.166 (0.280) | 0.302 (0.560) | |||

| year fixed effects | no | yes | no | no | no | yes |

| constant | ✓ | ✓ | 168.100*** (247.370) | 146.400*** (21.480) | 146.800*** (20.510) | 148.000*** (22.240) |

| R2 | - | - | 0.200 | 0.360 | 0.360 | 0.430 |

| n (state cohorts) | 208 | 208 | 208 | 208 | 208 | 208 |

| p value of F test | ||||||

| for joint significance | p = 0.009 | p = 0.210 | p = 0.247 | p = 0.066 | ||

| of 5M0, 5M5, 5M10 | ||||||

Notes: The values reported in Columns 1 are coefficients and clustered standard errors for three different regressions of average height in centimeters on each nmx measure separately. Column 2 repeats these same three regressions with controls. Columns 3-6 report coefficients from single regressions. Standard errors for all regressions are clustered at the state level and shown in parentheses.

p< 0.1

p< 0.05

p< 0.01

p < 0.001.

Columns 3-6 of table 3 present the results of regressions that include the three mortality rates in the same regression. Due to multicollinearity of the three nmx measures, one would not expect the individual coefficients on the nmx measures to remain statistically significant in this analysis, and they do not. However, the coefficients on the nmx measures are of the anticipated sign and the p values of F tests for the joint significance of 5m0, 5m5 and 5m10 show that the variables are jointly significant for all of the regressions.

It is noteworthy that, using data from the 1800s in Europe, [20] present the results of regressions similar to those in column 3 of table 3. They use the probability of dying, nqx, rather than mortality rates, nmx. When the nmx values in this analysis are converted to nqx values, assuming a constant death rate in the age interval, the magnitudes of the coefficients on the regressors in column 3 are consistent with the magnitudes of the coefficients estimated by [20].

This analysis finds that each of the measures of pre-adult mortality individually correlates with mean adult height for both men and women, and the rates are jointly significant in regressions containing all three rates. If pre-adult mortality is indeed measuring variation in the disease environment, then these regressions suggest that the disease environment was an important determining factor of adult heights in India.

4.3 Neonatal mortality, postneonatal mortality & children's height

Height is largely set quite early in life [55], so relationships between child height and early life mortality can be used to explore the likely determinants of the heights of the next generation of Indian adults. In this section, I take an approach similar to the one used above, and present the results of regressions of child height-for-age z-scores on state level measures of early life mortality. I find that neonatal mortality correlates with the heights for children much as it did with the heights of adults born two to three decades earlier.

Data from the NFHS 2 and 3 allow regressions of an individual child's height on neonatal and postneonatal mortality rates in the state where she was born, as well as controls for possibly confounding variables, such as the child's household socioeconomic status and her mother's height, which is a measure of the child's genetic potential. Table 4 presents the results of regressions of individual children's height-for-age z-scores, on state-survey round level neonatal mortality, postneonatal mortality and controls. It presents results separately for girls and boys. The coefficients in column 5 of table 4 were computed using OLS regressions of the following form:

| (3) |

where hfaihsr is the height-for-age z-score of child i in household h in state s in survey round r. NNMsr is the state and survey round specific neonatal mortality among children born in the three years before the survey. PNMsr is the state and survey round specific postneonatal mortality among children born in the three years before the survey. Ehsr is a vector of household-level controls for economic well-being; these have been described in section 3. mother′s heightihsr is the height in centimeters of the child's mother. Aihsr is a vector of age-in-months indicators, and εihsr is a child specific error term. All standard errors are clustered at the state round level; there are 52 state rounds.

Table 4.

Neonatal mortality, postneonatal mortality & child height in India

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| height for age z-scores | |||||

| Panel A: girls | |||||

| NNM | −0.025*** (0.003) | −0.019*** (0.003) | −0.013*** (0.003) | −0.012** (0.004) | |

| PNM | −0.026*** (0.004) | −0.011** (0.004) | −0.009* (0.004) | −0.009* (0.004) | |

| NFHS 3 | 0.324*** (0.064) | 0.251** (0.082) | 0.274*** (0.060) | 0.258*** (0.057) | 0.245*** (0.060) |

| mother's height | 0.045*** (0.002) | ||||

| asset variables | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| n (children under three) | 24504 | 24504 | 24504 | 24503 | 24416 |

| Panel B: boys | |||||

| NNM | −0.021*** (0.002) | −0.015*** (0.003) | −0.008* (0.004) | −0.008† (0.004) | |

| PNM | −0.023*** (0.003) | −0.011** (0.003) | −0.009* (0.004) | −0.010* (0.005) | |

| NFHS 3 | 0.307*** (0.060) | 0.238** (0.071) | 0.258*** (0.055) | 0.202*** (0.057) | 0.184** (0.058) |

| mother's height | 0.045*** (0.003) | ||||

| F-test on asset variables | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| n (children under three) | 26401 | 26401 | 26401 | 26396 | 26316 |

Notes: OLS regression model. Standard errors are clustered at the state-round level and shown in parentheses. Children under three from the NFHS 2 and the NFHS 3 are included in the regression. The dependent variable is height for age z-scores computed using the WHO 2006 standards. Indicators for age-in-months are included in each specification. Assets indicators are included in columns 4 and 5 for whether or not the child's household owns a radio, a TV, a fridge, a bicycle, a motorcycle, a car, and whether or not it has electricity. It also includes indicators for the type of drinking water the child's house uses (17 options). In all cases, these asset variables are jointly statistically significant. The variable NNM is the fraction of children born in the individual's state in the three years before the survey who died in the first month of life. The variable PNM is the fraction of children born in the individual's state in the three years before the survey who died between the second and twelfth months of life.

p < 0.1

p< 0.05

p< 0.01

p < 0.001.

Because the magnitudes of the coefficients are similar for girls and boys, I discuss only the coefficients in panel A of table 4, which gives results for girls. Indeed, none of the coefficients in panel B, for boys, is statistically significantly different from the corresponding coefficient in the girls table. This is perhaps surprising considering that the coefficients on state net domestic product were different for men and women in the adult regressions. If pre-natal nutrition is the main mechanism leading to both neonatal mortality and stunted heights, it makes sense that the coefficients on neonatal mortality would be similar; because parents would not have known the sex of the child before birth, they would not have been able to make differential investments in pregnancy. However, if parents are both able, and chose to better protect their male children from a bad disease environment, we might expect the coefficient on postneonatal mortality to be steeper for girls than for boys. That the coefficients on postneonatal mortality are similar for both boys and girls suggests that parents are either not able to modify the disease environment differentially, or are choosing not to do so.

Columns 1 and 2 show an association between state level neonatal and postneonatal mortality, respectively, and children's height. In column 3, when both NNM and PNM are included in the same regression, the magnitude of the coefficient on each of these predictors is smaller than when the predictor is entered individually, but both predictors have statistically significant coefficients. The magnitudes of the coefficients change little when controls for household level socioeconomic variables and mother's height are added.

The interquartile range for neonatal mortality in these data is 22 to 43 per 1000 and the interquartile range for postneonatal mortality is 11 to 23 per 1000. Therefore, both mortality measures have an interquartile range of about 20 per 1000. The coefficients on both NNM and PNM are approximately −0.01. This implies that a difference of 20 per 1000 of either neonatal or postneonatal mortality is associated with a difference about −0.2 standard deviations in average child height. For a three year old girl, 0.2 standard deviations is about three quarters of a centimeter. It is noteworthy that this height difference is very close to the effect size found for adult cohorts exposed to a similar difference in neonatal mortality regimes.16

5 Discussion

The correlations between height and postneonatal mortality and pre-adult mortality documented here likely reflect relationships between height and infectious diseases that both stunt growth and cause early death. However, prior papers have not found relationships between height and neonatal mortality. In these data, what are the early life conditions that stunt growth for which neonatal mortality likely proxies?

One factor that is likely to be be important is poor pre-natal nutrition, which has been, and continues to be, a widespread constraint on children's health in India [54, 13]. Pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) and weight gain during pregnancy are useful indicators of pre-natal nutrition that are predictive of birth weight [72]. Because India has no national monitoring system for maternal health, there are no data on these indicators. However, the BMI for women of child-bearing age can be used as a proxy for pre-pregnancy BMI. [25] analyze National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau (NNMB) data from 1975 to 1990, and find that about half of Indian women in the states covered by these data had BMI scores below 18.5, the WHO cutoff for underweight during this period. Improvements in pre-pregnancy body mass between the 1970s and 2005 seem to have been modest; the NFHS 3 found that more than a third of Indian women between the ages of 15 and 49 were underweight. Although there is no nationally representative data on weight gain during pregnancy, the [71]'s review of studies from India found that women in those studies gained an average of only seven kilograms during pregnancy.

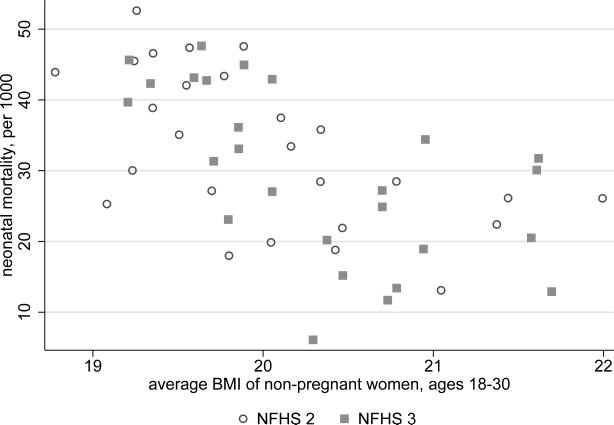

If poor pre-natal nutrition is indeed an important mechanism driving the relationship between neonatal mortality and height in these state level regressions, we would expect state level measures of pre-natal nutrition to correlate with the state level measures of neonatal mortality that are used in this paper. Figure 5 plots the neonatal mortality numbers used in section 4.3 against state level estimates of pre-pregnancy body mass. To estimate pre-pregnancy body mass, I use the average BMI of non-pregnant women aged 18-30 in each state; these ages represent the 10th and 90th percentiles of age among pregnant women both the NFHS 2 and the NFHS 3. Figure 5 shows a strong negative relationship between state level neonatal mortality and state level BMI of women of child bearing age; the correlation coefficient associated with these data is about −0.6. A similar plot of postneonatal mortality against women's body mass produces a much lower correlation, of only about −0.3. Although the data are not presented here, [30] reports that there was important spatial variation in indicators of women's nutrition in India during the 1970s and 1980s, which correlated with child outcomes, including neonatal mortality (see also [67]).

Figure 5. State level variation in women's body mass correlates with neonatal mortaity.

Observations are states in the NFHS 2 and the NFHS 3. The horizontal axis plots the average body mass index score of non-pregnant women age 18 to 30; these ages are the 10th and 90th percentile ages among pregnant women in both the NFHS 2 and the NFHS 3. The vertical axis plots neonatal mortality, the fraction of infants born in the three years before the survey who died in the rst month of life.

Of course, the interpretation that is being advanced here, that neonatal mortality proxies for poor pre-natal nutrition in the relationship between height and neonatal mortality, does not rule out that a high burden neonatal infection may also influence heights. However, large literatures link neonatal mortality to poor pre-natal nutrition, poor prenatal nutrition to low birth weight and low birth weight to height, whereas such a literature does not exist for neonatal infection and height. More research would be needed to fully characterize the relative importance of these two factors.

6 Conclusion

Using data from state cohorts born between 1970 and 1983 and from children in two rounds of the more recent NFHS surveys, this article has documented a negative relationships between height and measures of early life mortality in India. These findings contribute to the literature the first evidence from within a developing country of the associations between neonatal mortality and height. This finding is novel, since other authors who have looked at the relationships between early life mortality and height have not found an association between neonatal mortality and height. This literature has, however, used data from Europe and the United States in the 20th century, where there was little nutritional deprivation among mothers.

As in developed countries, this paper finds relationships between pre-adult mortality and the heights of adult cohorts, and between postneonatal mortality and children's height in the NFHS surveys, which suggests that variation in the disease environment predicts heights in India. Unlike in developed countries, however, aggregate income in early childhood, as measured by net state domestic product per capita in the year of birth, predicts adult heights in India. Unfortunately, this analysis cannot distinguish which mechanisms lead from income to adult height, nor why the coefficient for men is larger than the coefficient for women. Future research in this area should focus on exploring possible mechanisms, and determining whether they are the same for men and women.

Finally, it is likely that relationships between state level neonatal mortality and population heights at least in part reflect important state level variation in pre-natal nutrition. The extent to which poor pre-natal nutrition may have population-wide and lasting effects on the heights of Indians has not previously been well documented. Such an analysis is important not only for understanding the relationship between height and early life mortality, but also for public policy. If poor pre-natal nutrition not only affects infants’ chances of survival, but also stunts their heights, and therefore compromises their later life health and human capital accumulation, the welfare impacts of poor pre-natal nutrition in India may be importantly under-appreciated.

Highlights.

Reports on relationships between early life mortality and height in India

Finds that, in contrast to in developed countries, NNM predicts Indian heights

Suggests widespread maternal malnutrition may partially explain short Indian heights

Acknowledgments

Partial support for this research was provided by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (5R24HD047879).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

All errors are my own.

[59] finds that the Africa-India height gap can be statistically explained by Indians’ early life exposure to poor sanitary conditions measured by open defecation, and [38] focus on inequality among siblings of different sexes and birth orders. [50] discuss the interactions of low birth weight and infection in producing child undernutrition.

Indeed, [59] shows that the correlation between mothers’ heights and children's heights are lower in India and sub-Saharan Africa than in the United States.

The measures included 5q0, 5q5 and 5q10. These are the probability of dying between the ages of 0 and 5, between 5 and 10, and 10 and 15 years old respectively.

[66] provide evidence that the relative contribution of intrauterine growth retardation to low birth weights is greater in developing countries than in developed ones.

Indeed, in a 1996-2003 trial of home based neonatal sepsis management in Maharastra, India, researchers found that over four fifths of deaths from neonatal sepsis occurred in the first week of life [5].

More recently, research has focused on environmental enteropathy [43, 36, 59], which although not a main cause of mortality, may be another important cause of stunting.

Only “prematurity” was listed as a cause of death in this study, birth weight was not specifically mentioned. However, it is unlikely that this survey accounted for pregnancy length, or that women even knew the precise length of their pregnancies. Thus, any low birth weight infant who did not die from another obvious cause might have been said to have died from “prematurity.”

The SRS reports NNM, PNM, IMR, and other mortality rates for each year between 1970 and 1983 in the following states: Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Gujarat, Harayana, Himachal Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharastra, Orissa, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh. There is no data for union territories in the SRS.

These states are: Sikkim, which had previously been a British protectorate and was founded in 1975; Tripura, Meghalaya and Manipur, all of which were founded in 1972; Arunchal Pradesh, which was formed as a union territory out of Assam in 1972, and became state in 1987. An early report on the SRS from the Office of the Registrar General suggests that data from the region that became the union territory of Arunchal Pradesh were not included in the Assam estimates from 1970-1972. Together, these omitted states made up less than 1% of the population of India in the 2011 census.

[23] points out that child mortality (a large fraction of which is infant mortality) was much higher in India than in neighboring China during this period, and that the decline in child mortality was much slower.

For more on using the WHO 2006 charts in the Indian context, see [61].

There is a notable exception to this statement, though the infant mortality rates required to produce a “turning point” are outside the range of most modern human experience. [31] find that the adult heights of people who were children during the Great Chinese Famine (1959-1961), during which mortality rates were estimated to be about 200 per 1000 [4], are no different than the heights of cohorts born just before or just after the famine. The heights of their children, however, are taller than the children of cohorts born just before, or just after the famine. The authors interpret this as evidence that those who survived the famine were selected on the basis of their health, that is, that they had the genetic potential to be tall. However, this genetic potential was not realized due to famine conditions in infancy and childhood, which stunted them.

The following states are coded as northern states: Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Harayana, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Assam, West Bengal, Orissa, Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat. Not included among the northern states are Maharastra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

That the magnitude of the coefficients on 5m10 is so much greater than those on 5m0 is likely due, in large part, to a mechanical relationship resulting from the fact that values for 5m0 are about 20 times the size of values of 5m10.

[69] finds that much of absolute height deficit among adults in developing countries is set by the time they are five years old.

References

- 1.Adair Linda S. Size at birth and growth trajectories to young adulthood. American Journal of Human Biology. 2007;19:327–337. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.20587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akachi Yoko, Canning David. Health trends in Sub-Saharan Africa: Conflicting evidence from infant mortality rates and adult heights. Economics & Human Biology. 2010;8(2):273–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alderman Harold, Lokshin Michael, Radyakin Sergiy. Tall claims: Mortality selection and the height of children in India. Economics & Human Biology. 2011;9(4):393–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashton Basil, Hill Kenneth, Piazza Alan, Zeitz Robin. Famine in China, 1958-1961. Population and Development Review. 1984;10(4):613–645. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bang Abhay, Bang Rani, Stoll Barbara, Baitule Sanjay, Reddy Hanimi, Deshmukh Mahesh. Is home-based diagnosis and treatment of neonatal sepsis feasible and effective? Seven years of intervention in the Gadchiroli field trial (1996 to 2003). Journal of Perinatology. 2005;25:S62–S71. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barcellos Silvia, Carvalho Leandro, Lleras-Muney Adriana. Child gender and parental investments in india: Are boys and girls treated differently? American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 2014;6(1):157–189. doi: 10.1257/app.6.1.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barros Fernando, Huttly Sharon, Victora Cesar, Kirkwood Betty, Patrick Vaughan J. Comparison of the causes and consequences of prematurity and intrauterine growth retardation: A longitudinal study in southern Brazil. Pediatrics. 1992;90(2):238–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Behrman Jere. Intrahousehold allocation of nutrients in rural India: Are boys favored? Do parents exhibit inequality aversion? Oxford Economic Papers. 1988;40(1):32–54. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Behrman Jere, Rosenzweig Mark. Returns to birthweight. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2004;86(2):586–601. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhalotra Sonia. fatal fluctuations? cyclicality in infant mortality in india. Journal of Development Economics. 2010;93(1):7–19. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mari Bhat PN. On the trail of ‘missing’ Indian females: II: Illusion and reality. Economic and Political Weekly. 2003;37(52):5244–5263. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mari Bhat PN, Preston Samuel, Dyson Tim. Vital rates in India, 1961-1981. Report 24, Committee on Population and Demography. 1984.

- 13.Bhutta Zulfiqar A, Gupta Indu, de'Silva Harendra, Manandhar Dharma, Awasthi Shally, Hossain SM, Salam MA. Maternal and child health: Is South Asia ready for change? BMJ. 2004;328(7443):816–819. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7443.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Binkin Nancy J., Yip Ray, Fleshood Lee, Trowbridge Frederick. Birth weight and childhood growth. Pediatrics. 1988;82:828–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borooah Vani K. Gender bias among children in India in their diet and immunisation against disease. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58(9):1719–1731. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00342-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bozzoli Carlos, Deaton Angus, Quintana-Domeque Climent. Adult height and childhood disease. Demography. 2009;46(4):647–669. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colin Cameron A, Gelbach Jonah B., Miller Douglas L. Bootstrap-based improvements for inference with clustered errors. The Review of Economics and Statistics. 2008;90(3):414–427. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Case Anne, Paxson Christina. Stature and status: Height, ability, and labor market outcomes. Journal of Political Economy. 2008;116:499–532. doi: 10.1086/589524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Checkley William, Buckley Gillian, Gilman Robert, Assis Ana, Guerrant Richard, Morris Saul, Mølbak Kare, Valentiner-Branth Palle, Lanata Claudio, Black Robert. Multi-country analysis of the effects of diarrhoea on childhood stunting. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2008;37:816–830. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crimmins Eileen, Finch Caleb. Infection, inflammation, height and longevity. Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences. 2006;103(2):498–503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501470103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das Gupta Monica. Perspectives on women's autonomy and health outcomes. American Anthropologist. 1995;97(3):481–491. [Google Scholar]

- 22.De Onis Mercedes. Technical report. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2006. WHO child growth standards: Length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for-age: Methods and development. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deaton Angus. WIDER Annual Lecture 10. UNU World Institute for Development Economics Research; 2006. Global patterns of income and health: Facts, interpretations, and policies. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deaton Angus. Height, health & inequality: The distribution of adult heights in India. AEA Papers and Proceedings. 2008;98(2):468–474. doi: 10.1257/aer.98.2.468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deaton Angus, Drèze Jean. Nutrition in India: Facts and interpretations. Economic & Political Weekely. 2009;XLIV(7):42–65. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dréze Jean, Sen Amartya. Indian development: Selected regional perspectives. Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Duke T. Neonatal pneumonia in developing countries. Archives of Disease in Childhood–Fetal Neonatal Edition, 90:F211F219. 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.EPW Research Foundation Domestic product of states of India : 1960-61 to 2006-07, 2nd updated edition. Technical report. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fogel Robert. The Escape from Hunger and Premature Death, 1700–2100: Europe, America, and the Third World. Cambridge University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gopalan C. The mother and child in India. Economic and Political Weekly. 1985;20(4):159–166. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gørgens Tue, Meng Xin, Vaithianathan Rhema. Stunting and selection effects of famine: A case study of the Great Chinese Famine. Journal of Development Economics. 2012;97:99–111. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Government of India Vital Statistics of India for 1963-4: Based on civil registration system, volume 134. Office of the Registrar General. 1968 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Government of India Survey on Infant and Child Mortality, 1979. Office of the Registrar General. 1979 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hatton Timothy. Infant mortality and the health of survivors: Britain, 1910-50. The Economic History Review. 2011;64(3):951–972. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0289.2010.00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hatton Timothy J. How have europeans grown so tall? Oxford Economic Papers. 2013;66:349–372. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Humphrey Jean. Child undernutrition, tropical enteropathy, toilets, and handwashing. Lancet. 2009;374:1032–1035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60950-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hytten FE. Nutrition in pregnancy. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 1979;55:2934–2939. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.55.643.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jayachandran Seema, Pande Rohini. working paper. Northwestern University; 2013. Why are Indian children shorter than African children? [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jeffrey Patricia, Jeffrey Roger, Lyon Andrew. Labour Pains and Labour Power: Women and Childbearing in India. Zed Book Ltd.; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jousilahti P, Tuomilehto J, Vartiainen E, Eriksson J, Puska P. Relation of adult height to cause-specific and total mortality: A prospective follow-up study of 31,199 middle-aged men and women in Finland. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2000;151:11121120. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Komlos John. Shrinking in a growing economy? the mystery of physical stature during the industrial revolution. Journal of Economic History. 1998;58:779–802. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Komlos John. Access to food and the biological standard of living: perspectives on the nutritional status of native Americans. The American Economic Review. 2003;93(1):252–255. doi: 10.1257/000282803321455250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Korpe Poonam, Petri William. Environmental enteropathy: critical implications of a poorly understood condition. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2012;18(6):328–336. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kramer Michael S. Intrauterine growth and gestational duration determinants. Pediatrics. 1987;80(4):502–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kusin Jane, Kardjati Sri, Houtkooper Joop, Renqvist UH. Energy supplementation during pregnancy and postnatal growth. The Lancet. 1992;340(8820):623–626. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92168-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kusin Jane, Kardjati Sri, Renqvist UH. Chronic undernutrition in pregnancy and lactation. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 1993;52:19–28. doi: 10.1079/pns19930033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maccini Sharon, Yang Dean. Under the weather: Health, schooling, and economic consequences of early-life rainfall. The American Economic Review. 2009:1006–1026. doi: 10.1257/aer.99.3.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Million Death Collaborators Causes of neonatal and child mortality in India: A nationally representative mortality survey. The Lancet. 2010;376:1853–1860. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61461-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Munshi Kaivan, Rosenzweig Mark. Why is mobility in India so low?: Social insurance, inequality, and growth. NBER Working Paper. 2009;(14850) [Google Scholar]

- 50.Osmani Siddiq, Sen Amartya. The hidden penalties of gender inequality: fetal origins of ill-health. Economics & Human Biology. 2003;1(1):105–121. doi: 10.1016/s1570-677x(02)00006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Palriwala Rajni. Economics and patriliny: Consumption and authority within the household. Social Scientist. 1993;21(9/11):47–73. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pande Rohini P. Selective gender differences in childhood nutrition and immunization in rural India: The role of siblings. Demography. 2003;40(3):395–418. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Preston S, Hill M, Drevenstedt G. Childhood conditions that predict survival to advanced ages among African Americans. Social Science and Medicine. 1998;47:1231–1236. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00180-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ramalingaswami Vulimiri, Jonsson Urban, Rohde Jon. Commentary: The Asian enigma. The progress of nations, United Nations Childrens Fund. 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schmidt IM, Jorgensen MH, Michaelsen KF. Height of conscripts in Europe: Is postneonatal mortality a predictor? Annals of Human Biology. 1995;22(1):57–67. doi: 10.1080/03014469500003702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Silventoinen Karri. Determinants of variation in adult body height. Journal of Biosocial Sciences. 2003;35:263–285. doi: 10.1017/s0021932003002633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sokal DC, Imboua-Bogui G, Soga G, Emmou C, Jones TS. Mortality from neonatal tetanus in rural Côte d'Ivoire. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1988;66(1):69–76. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spears Dean. Height and cognitive achievement among Indian children. Economics and Human Biology. 2012;10:210–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spears Dean. How much international variation in height can sanitation explain? World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. 2013;(6351) [Google Scholar]

- 60.Steckel Richard H. Height and per capita income. Historical Methods: A Journal of Quantitative and Interdisciplinary History. 1983;16(1):1–7. doi: 10.1080/01615440.1983.10594092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tarozzi Alessandro. Growth reference charts and the nutritional status of indian children. Economics & Human Biology. 2008;6(3):445–468. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tripathi Amarnath, Srivastra Shraddha. Interstate migration and changing food preferences in India. Ecology of Food and Nutrition. 2011;50(5):410–428. doi: 10.1080/03670244.2011.604586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.UNICEF Elimination of maternal and neonatal tetanus. 2011 http://www.unicef.org/health/index_43509.html.

- 64.UNICEF & WHO . Low birthweight: Country, regional and global estimates. UNICEF; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Victora Cesar, Barros Fernando, Kirkwood Betty, Patrick Vaughan J. Pneumonia, diarrhea, and growth in the first 4 years of life: A longitudinal study of 5914 urban Brazilian children. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1990;52(39):1–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/52.2.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Villar José, Belizán José. The relative contribution of prematurity and fetal growth retardation to low birthweight in developing and developed societies. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1982;143:793–798. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(82)90012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Visaria Leela. Infant mortality in India: Level, trends and determinants. Economic & Political Weekly. 1985;20(32):1352–1359. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vogl Tom. Height, skills, and labor market outcomes in Mexico. working paper. Harvard University; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Waterlow JC. Reflections on stunting. In: Pasternak Charles., editor. Access not Excess. Smith–Gordon; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 70.WHO WHO Anthro for personal computers, version 3.2.2. 2011 http://www.who.int/childgrowth/software/en/

- 71.World Health Organization Maternal anthropometry and birth outcomes: A WHO collaborative study. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1995 supplement to volume 73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yaktine Ann L, Rasmussen Kathleen M. Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]