Abstract

Escherichia coli maltose-binding protein (MBP) is exceptionally effective at promoting the solubility of its fusion partners. However, there are conflicting reports in the literature claiming that 1) MBP is an effective solubility enhancer only when it is joined to the N-terminus of an aggregation-prone passenger protein, and 2) MBP is equally effective when fused to either end of the passenger. Here, we endeavor to resolve this controversy by comparing the solubility of a diverse set of MBP fusion proteins that, unlike those analyzed in previous studies, are identical in every way except for the order of the two domains. The results indicate that fusion proteins with an N-terminal MBP provide an excellent solubility advantage along with more robust expression when compared to analogous fusions in which MBP is the C-terminal fusion partner. We find that only intrinsically soluble passenger proteins (i.e., those not requiring a solubility enhancer) are produced as soluble fusions when they precede MBP. We also report that even subtle differences in inter-domain linker sequences can influence the solubility of fusion proteins.

Keywords: Gateway cloning, fusion protein, inclusion bodies, MBP, solubility enhancer

The post-genomic era has witnessed a huge evolution in the field of protein production. This was mainly a consequence of advances in the field of molecular biology and associated biotechnological applications. Novel methods are continuously being added to the existing pool of protein expression and purification systems. Even so, Escherichia coli is still considered to be the powerhouse of protein production. Its main disadvantage, however, is the frequent formation of inclusion bodies during overexpression. Accordingly, much research has focused on overcoming this bottleneck [1].

One particularly effective means of avoiding the formation of insoluble aggregates during protein expression in E. coli is to fuse an aggregation-prone protein to a highly soluble partner [2]. One of the most effective solubilizing fusion partners is E. coli maltose-binding protein (MBP) [3, 4]. The mechanism of solubility enhancement by MBP has been studied in some detail [5–10]. It is thought that MBP functions as a “holdase”, maintaining an aggregation-prone passenger protein in a soluble state until it either folds spontaneously or with the assistance of endogenous molecular chaperones. Alternatively, in some cases the fusion protein may persist in the form of a soluble aggregate [11]. It has been proposed that MBP inhibits the formation of insoluble aggregates by transiently binding folding intermediates of an aggregation-prone passenger protein, effectively sequestering it in an intramolecular interaction that impedes the kinetically competing pathway of intermolecular aggregation and precipitation [4]. A corollary of this hypothesis is that MBP must be folded before it can bind to and sequester its passenger protein [6, 9]. If so, then as a result of co-translational folding, it follows that MBP should function as a more effective solubilizing agent when it is fused to the N-terminus of a passenger protein than to its C-terminus because in the former case MBP would emerge first from the ribosome and have time to fold before the passenger protein is translated.

Consistent with this model, Sachdev and Chirgwin found that the aspartic proteases pepsinogen and procathepsin D were soluble in E. coli when MBP was fused to their N-termini but formed inclusion bodies when the order of the fusion partners was reversed [12]. However, a subsequent study claimed that MBP could function as a solubility enhancer irrespective of which end of the passenger protein it was fused to [13]. In the current work, we have attempted to resolve this controversy by comparing the solubility of a set of MBP fusion proteins in both orientations. In contrast to the previous studies, the MBP fusion proteins that we compare here are identical in every respect (e.g., their interdomain linker sequences) except for the order of the two domains.

Materials and methods

Materials

All materials of the highest available purity were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Rockford, IL, USA), Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), American Bioanalytical Inc. (Natick, MA, USA), EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA, USA), or Roche Diagnostics Corp. (Indianapolis, IN, USA), unless otherwise mentioned.

Construction of expression vectors

We used the Gateway multi-site recombinational cloning to assemble the N-terminal and C-terminal MBP fusion protein expression vectors. The appropriate attB sites (attB1, attB2 or attB3) were incorporated into the gene-specific primers (Tables 1 and 2). The N-terminal and C-terminal open reading frames (ORFs) were generated using standard PCR and were inserted into pDONR208 and pDONR209, respectively (Life Technologies Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA). The ORFs encoding green fluorescent protein (GFP) [4], dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) [7], dual specificity phosphatase 14 (DUSP14) [14], and tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease [15] were described previously. The MBP ORF was amplified from pDEST566 (Protein Expression Laboratory, Leidos Biomedical Research, Inc., Frederick, MD, USA; Addgene plasmid 11517) without the His6 tag. Entry clones were sequence verified and subsequently recombined in tandem into the destination vector pDEST527 (PEL, Leidos Biomedical Research; Addgene plasmid 11518) to create the fusion protein expression vectors. For example, the His-GFP-MBP fusion vector was constructed in three steps. First, the GFP ORF was PCR amplified using the forward primer PE-2688 (attB1-GFP) and the reverse primer PE-2689 (GFP-attB3), and the PCR product was recombined into pDONR208 (BP reaction). Second, the MBP ORF was PCR amplified using two partially overlapping forward primers, PE-2690 (attB3-overlap), PE-2691 (overlap-MBP) and a single reverse primer, PE-2692 (MBP-attB2) (Table 1). The overlap region in the forward primers corresponds to amino acids P1 to P6 of the TEV protease recognition site. This PCR product was recombined into pDONR209 (BP reaction). Third, inserts from both the N-terminal and C-terminal entry clones were recombined in tandem into pDEST527 (LR reaction), which includes an N-terminal polyhistidine tag in frame with the Gateway cloning cassette. Hence, the final recombination product expressed a tripartite His-GFP-MBP fusion protein with an attB1 site between the His-tag and GFP and an attB3 site between GFP and MBP. All of the fusion protein expression vectors also included a canonical TEV protease recognition site (ENLYFQG) between MBP and the passenger protein or between the passenger protein and MBP (depending on the orientation), except for the vectors encoding TEV protease fusion proteins, which contained an uncleavable recognition site (ENLYFQP) instead [16]. The P1' proline substitution in the TEV recognition site of the His-TEV-MBP fusion vector was created by site-directed mutagenesis of the C-terminal entry clone using specific mutagenic primers (PE-2728, PE-2729) and a QuikChange Lightning Kit (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA), while the P1' proline substitution in the His-MBP-TEV vector was contained in the gene-specific PCR primer (PE-578) used to amplify the TEV ORF for recombination into pDONR209. These mutant entry clones were used in the subsequent LR reactions to give either His-TEV-MBP or His-MBP-TEV. The coding sequence for the catalytic domain of Y. pestis YopH was PCR amplified using primers PE-2753 (Table 1) and PE-2755 (5'-GGG GAC AAC TTT GTA CAA GAA AGT TGC ATT AGC TAT TTA ATA ATG GTC G-3') from a full-length YopH clone (pKM835) and recombined into pDONR221 (Life Technologies) to generate an entry clone. This entry clone was subsequently recombined into pDEST527 to create the His-YopH expression vector. Other His-passenger expression vectors used in this study were reported previously [10]. All reactions were carried out as per the manufacturer’s protocol.

Table 1.

Primers used in construction of entry clones for C-terminal MBP fusions

| Primers | ORF | Sequence (5' to 3') |

|---|---|---|

| PE-2688 | GFP-F | GGG GAC AAC TTT GTA CAA AAA AGT TGT GAT GAG TAA AGG AGA AG |

| PE-2689 | GFP-R | GGG GAC AAC TTT GTA TAA TAA AGT TGC TTT GTA TAG TTC ATC CAT G |

| PE-2690 | - | GGG GAC AAC TTT ATT ATA CAA AGT TGT GGA GAA CCT GTA CTT CCA G |

| PE-2691 | MBP-F | GAG AAC CTG TAC TTC CAG GGT ATG AAA ATC GAA GAA GG |

| PE-2692 | MBP-R | GGG GAC AAC TTT GTA CAA GAA AGT TGC ATT ACG AAT TAG TCT GCG C |

| PE-2713 | DHFR-F | GGG GAC AAC TTT GTA CAA AAA AGT TGT GAT GGT TGG TTC GCT AAA C |

| PE-2714 | DHFR-R | GGG GAC AAC TTT GTA TAA TAA AGT TGC ATC ATT CTT CTC ATA TAC |

| PE-2715 | DUSP14-F | GGG GAC AAC TTT GTA CAA AAA AGT TGT GAT GAT TTC CGA GGG AG |

| PE-2716 | DUSP14-R | GGG GAC AAC TTT GTA TAA TAA AGT TGC GTG TCG GGA CTC CTT C |

| PE-2726 | TEV protease-F | GGG GAC AAC TTT GTA CAA AAA AGT TGT GGA AAG CTT GTT TAA GGG GCC GCG TG |

| PE-2727 | TEV protease-R | GGG GAC AAC TTT GTA TAA TAA AGT TGC GCG ACG GCG ACG ACG ATT CAT G |

| PE-2728 | - | GGA GAA CCT GTA CTT CCA GCC TAT GAA AAT CGA AGA AGG T |

| PE-2729 | - | ACC TTC TTC GAT TTT CAT AGG CTG GAA GTA CAG GTT CTC C |

| PE-2753 | YopH-F | GGG GAC AAC TTT GTA CAA AAA AGT TGT GCG TGA ACG ACC ACA CAC |

| PE-2754 | YopH-R | GGG GAC AAC TTT GTA TAA TAA AGT TGC GCT ATT TAA TAA TGG TCG |

Table 2.

Primers used in construction of entry clones for N-terminal MBP fusions

| Primers | ORF | Sequence (5' to 3') |

|---|---|---|

| PE-2690 | - | GGG GAC AAC TTT ATT ATA CAA AGT TGT GGA GAA CCT GTA CTT CCA G |

| PE-2717 | MBP-F | GGG GAC AAC TTT GTA CAA AAA AGT TGT GAT GAA AAT CGA AGA AGG |

| PE-2718 | MBP-R | GGG GAC AAC TTT GTA TAA TAA AGT TGC CGA ATT AGT CTG CGC |

| PE-2719 | GFP-F | GAG AAC CTG TAC TTC CAG GGT ATG AGT AAA GGA GAA G |

| PE-2720 | GFP-R | GGG GAC AAC TTT GTA CAA GAA AGT TGC ATT ATT TGT ATA GTT CAT CCA TG |

| PE-2721 | DHFR-F | GAG AAC CTG TAC TTC CAG GGT ATG GTT GGT TCG CTA AAC |

| PE-2722 | DHFR-R | GGG GAC AAC TTT GTA CAA GAA AGT TGC ATT AAT CAT TCT TCT CAT ATA C |

| PE-2723 | DUSP14-F | GAG AAC CTG TAC TTC CAG GGT ATG ATT TCC GAG GGA G |

| PE-2724 | DUSP14-R | GGG GAC AAC TTT GTA CAA GAA AGT TGC ATT AGT GTC GGG ACT CCT TC |

| PE-2725 | TEV protease-R | GGG GAC AAC TTT GTA CAA GAA AGT TGC ATT AGC GAC GGC GAC GAC GAT TCA TG |

| PE-578 | TEV protease-F | GAG AAC CTG TAC TTC CAG CCG GAA AGC TTG TTT AAG GGG CCG CGT G |

Construction of “att” site mutants

The complementary mutagenic primers, PE-2765 and 2766 were used to make ΔattB1 mutants of all N-terminal MBP fusions. These primers anneal to the flanking regions of attB1 and loop out the template region (attB1) to be deleted when the primer-template duplex is formed in a QuikChange reaction. The expression vectors prepared by multisite-gateway cloning were used as the templates. The attB3 to attB1 change in the N-terminal MBP fusion junctions was made using the complementary mutagenic primers PE-2770 and PE-2771 (Table 3) with the ΔattB1 mutants as templates in a second round of QuikChange reactions. These primers anneal to the flanking regions of attB3 and replace the attB3 sequence with attB1.

Table 3.

Primers used for construction of attB1 and attB3 mutants

| Primers | Change | Sequence (5' to 3') |

|---|---|---|

| PE-2765 | ΔattB1 | CCC ACC ATC ACC ATC ACC ATA TGA AAA TCG AAG AAG GTA |

| PE-2766 | ΔattB1 | TAC CTT CTT CGA TTT TCA TAT GGT GAT GGT GAT GGT GGG |

| PE-2770 | attB3 to attB1 | GAC GCG CAG ACT AAT TCG ATC ACA AGT TTG TAC AAA AAA GCA GGC TCG GAG AAC CTG TAC TTC CAG |

| PE-2771 | attB3 to attB1 | CTG GAA GTA CAG GTT CTC CGA GCC TGC TTT TTT GTA CAA ACT TGT GAT CGA ATT AGT CTG CGC GTC |

| PE-2787 | ΔattB1 | CCC ACC ATC ACC ATC ACC ATA TGA GTA AAG GAG AAG AAC |

| PE-2788 | ΔattB1 | GTT CTT CTC CTT TAC TCA TAT GGT GAT GGT GAT GGT GGG |

| PE-2789 | ΔattB1 | CCC ACC ATC ACC ATC ACC ATA TGG TTG GTT CGC TAA AC |

| PE-2790 | ΔattB1 | GTT TAG CGA ACC AAC CAT ATG GTG ATG GTG ATG GTG GG |

| PE-2791 | ΔattB1 | CCC ACC ATC ACC ATC ACC ATA TGA TTT CCG AGG GAG |

| PE-2792 | ΔattB1 | CTC CCT CGG AAA TCA TAT GGT GAT GGT GAT GGT GGG |

| PE-2793 | ΔattB1 | CCC ACC ATC ACC ATC ACC ATG AAA GCT TGT TTA AGG GG |

| PE-2794 | ΔattB1 | CCC CTT AAA CAA GCT TTC ATG GTG ATG GTG ATG GTG GG |

| PE-2795 | attB3 to attB1 | ATG GAT GAA CTA TAC AAA ATC ACA AGT TTG TAC AAA AAA GCA GGC TCG GAG AAC CTG TAC TTC CAG |

| PE-2796 | attB3 to attB1 | CTG GAA GTA CAG GTT CTC CGA GCC TGC TTT TTT GTA CAA ACT TGT GAT TTT GTA TAG TTC ATC CAT |

| PE-2797 | attB3 to attB1 | GTA TAT GAG AAG AAT GAT ATC ACA AGT TTG TAC AAA AAA GCA GGC TCG GAG AAC CTG TAC TTC CAG |

| PE-2798 | attB3 to attB1 | CTG GAA GTA CAG GTT CTC CGA GCC TGC TTT TTT GTA CAA ACT TGT GAT ATC ATT CTT CTC ATA TAC |

| PE-2799 | attB3 to attB1 | GAG AAG GAG TCC CGA CAC ATC ACA AGT TTG TAC AAA AAA GCA GGC TCG GAG AAC CTG TAC TTC CAG |

| PE-2800 | attB3 to attB1 | CTG GAA GTA CAG GTT CTC CGA GCC TGC TTT TTT GTA CAA ACT TGT GAT GTG TCG GGA CTC CTT CTC |

| PE-2801 | attB3 to attB1 | AAT CGT CGT CGC CGT CGC ATC ACA AGT TTG TAC AAA AAA GCA GGC TCG GAG AAC CTG TAC TTC CAG |

| PE-2802 | attB3 to attB1 | CTG GAA GTA CAG GTT CTC CGA GCC TGC TTT TTT GTA CAA ACT TGT GAT GCG ACG GCG ACG ACG ATT |

Since the flanking residues of the target regions were different in His-passenger-MBP fusions, we had to design a unique pair of complementary mutagenic primers for each of them (Table 3). The ΔattB1 mutants were made using complementary mutagenic primers specific for GFP (PE-2787/PE-2788), DHFR (PE-2789/PE-2790), DUSP14 (PE-2791/PE-2792) and TEV protease (PE-2793/PE-2794). The expression vectors prepared by multisite-gateway cloning were used as the templates in QuikChange reactions as outlined above. Similarly, the attB3 to attB1 changes at the passenger-MBP fusion junctions were made using pairs of complementary mutagenic primers specific for GFP (PE-2795/PE-2796), DHFR (PE-2797/PE-2798), DUSP14 (PE-2799/PE-2800) and TEV protease (PE-2801/PE-2802). These primers anneal to the flanking regions of attB3 and replace the attB3 sequence with attB1. The ΔattB1 mutants were used as templates for the second round of QuikChange reactions.

The QuikChange Lightning Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies) was used for engineering these desired modifications throughout. The reaction was performed as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Mutagenic primer sequences are listed in Table 3. All mutants were confirmed experimentally.

Expression and solubility analysis

E. coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIL cells (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, CA) were used for all protein expression experiments. Cells harboring one of the protein expression vectors (see above) were grown to mid-log phase (A600 ~ 0.5) at 37 °C in Luria broth supplemented with 100 µg ml−1 ampicillin and 30 µg ml−1 choloramphenicol, at which time production of the fusion protein was induced by the addition of IPTG to 1 mM and the temperature was reduced to 30 °C. Four hours later, the cells were pelleted by centrifugation and re-suspended in approximately 0.2 culture volume (corresponding to an A600 of 10.0) of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA). The cells were disrupted by sonication. A total protein sample was collected from the cell suspension after sonication, and a soluble protein sample was collected from the supernatant after the insoluble debris was pelleted by centrifugation at 20,000g. These samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and proteins were visualized by staining with Coomassie Brilliant Blue.

Coomassie-stained gels were scanned with an Alpha Innotech AlphaEase FC Imaging System and the pixel densities of the bands corresponding to the fusion proteins were obtained by volumetric integration. In each pair of lanes (total and soluble), the collective density of all proteins that are larger than the fusion protein was also measured and used to normalize the values obtained for the fusion protein bands in the two lanes. The percent solubility of each fusion protein was calculated by dividing the amount of soluble fusion protein by the total amount of fusion protein in the cells after normalization of these two values.

Results and discussion

Initially, a Gateway destination vector with the cloning cassette upstream from and in frame with mature MBP was created to serve as the starting point for the construction of expression vectors that would produce passenger proteins with MBP fused to their C-termini. Green fluorescent protein (GFP), dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), dual specificity phosphatase 14 (DUSP14), and tobacco etch virus protease (TEV), preceded by properly situated ribosome binding sites, were then fused to the N-terminus of MBP by recombinational cloning. However, these fusion protein expression vectors produced very little protein (data not shown), probably due to inefficient translation. Indeed, a principal advantage of N-terminal tags is that they typically provide a consistent and favorable context for translation initiation.

To overcome the problem of poor expression, the fusion protein expression vectors were redesigned so that they would all have the same 5' untranslated mRNA (including the ribosome binding site) and N-terminal amino acid sequences. This was accomplished by using multi-site Gateway cloning and the destination vector pDEST527 (see Materials and Methods) to create tripartite fusions consisting of a polyhistidine tag followed, respectively, by the attB1 recombination site, the passenger protein ORF, the attB3 recombination site, the MBP ORF, and the attB2 recombination site. A matching set of otherwise identical fusion protein expression vectors was constructed in which the MBP domains preceded the passenger proteins. Although this strategy resulted in consistently higher expression levels of all the fusion proteins as intended, the solubility of the His-MBP-passenger fusions was very poor (data not shown). This result was unexpected because analogous His-MBP-passenger fusion proteins constructed by single site Gateway cloning using the destination vector pDEST-HisMBP [17] were moderately to highly soluble [10].

There were only two regions in which the amino acid sequences of the insoluble His-MBP-passenger fusion proteins assembled by multi-site cloning and the soluble His-MBP-passenger fusion proteins constructed by single site cloning differed. First, in the multi-site fusion proteins, the polyhistidine tag was flanked by additional amino acids on its N-terminal and C-terminal ends, with the latter residues corresponding to the translation product of the attB1 recombination site (TSLYKKVV). Second, the linker sequence between MBP and the passenger proteins was the translation product of the attB3 recombination site (ATLLYKVV) in the multisite fusion proteins, whereas it was the slightly different attB1 translation product in the single site fusions (TSLYKKAG). Deleting the attB1 residues from the C-terminal side of the polyhistidine tag in the multi-site fusions resulted in a modest improvement in solubility (data not shown). Replacing the attB3 site between MBP and the passengers with the attB1 site resulted in a substantial additional improvement in solubility. These findings underscore the fact that even minor alterations to linker sequences can have profound effects on solubility and should serve as a cautionary tale to protein engineers. Similar effects have been noted previously [18].

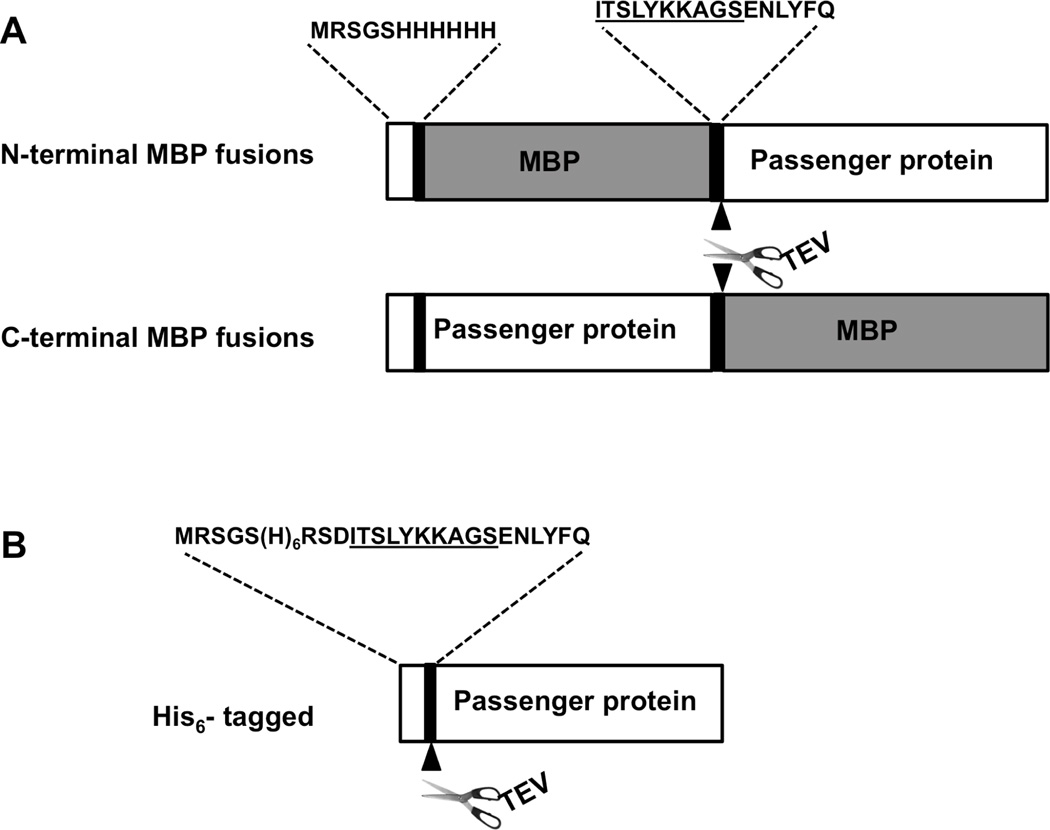

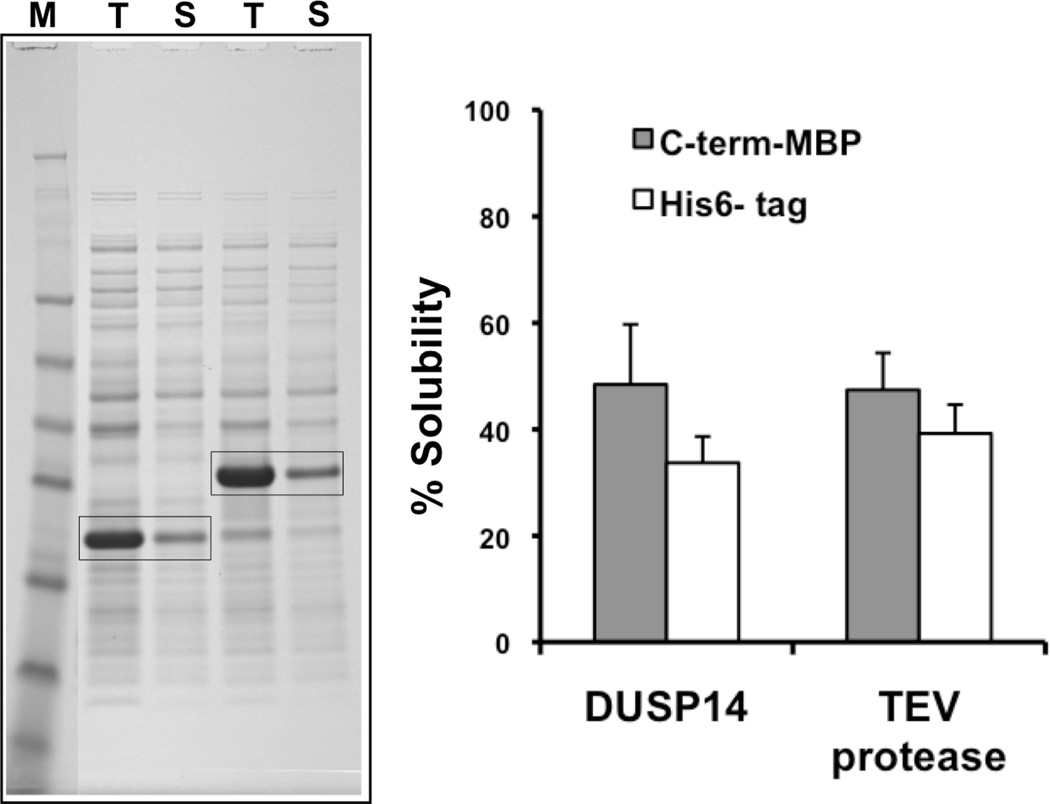

The structures of the modified His-MBP-passenger and His-passenger-MBP fusion protein expression vectors are depicted in Figure 1A. The amino acid sequences of the N-terminal polyhistidine tags and interdomain attB1 linkers (followed by TEV protease cleavage sites) are identical in both N- and C-terminal MBP fusion proteins. When the solubility of the four pairs of fusion proteins was compared, for two of the passenger proteins (GFP and DHFR) the solubility was much greater when the MBP domain preceded the passenger (Figure 2) than it was when they were synthesized in the opposite order. In the other two cases (DUSP14 and TEV protease), the trend was the same but the difference was not as great. Additionally, all of the fusion proteins in which the passenger preceded MBP were invariably expressed at a lower level than those in which MBP preceded the passenger (compare Figures 2A and 2B), even though the 5' untranslated mRNA and first 11 codons of the ORFs were identical in all cases. This suggests that apart from efficient translation initiation, N-terminal MBP may confer some additional advantage that increases the yield of fusion proteins.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation (not to scale) of the MBP fusion proteins (A) and His-tagged proteins (B). The attB1-derived linker is underlined. The sequences at the junction, TEV-protease cleavage site and His-tag are marked as well.

Figure 2.

Solubility comparisons. Samples of total (T) and soluble (S) intracellular proteins were prepared as described (see Materials and Methods) and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. (A) and (B) represent N-terminal and C-terminal MBP fusions, respectively. The overexpressed fusion proteins are surrounded by boxes. (C) Solubility estimate obtained from gel scans. (Values are the mean ± SD of 3 separate determinations).

Seeking to understand why the His-DUSP14-MBP and His-TEV-MBP fusion proteins exhibited such unexpectedly high solubility, the solubility of His-DUSP14 and His-TEV was examined (Figure 1B). These His-tag expression vectors were described previously [10]. As shown in Figure 3, a significant fraction of the His-tagged passengers was soluble under the same experimental conditions. Hence, it appears that the partial solubility of the His-DUSP14-MBP and His-TEV-MBP fusion proteins can be attributed to spontaneous folding of the passengers (since the polyhistidine-tagged proteins approximate the unfused state) rather than MBP-mediated solubility enhancement. If so, then it follows that a soluble passenger protein (one that requires no solubility-enhancing fusion partner) should be indifferent to the position of MBP in a fusion protein.

Figure 3.

The C-terminal MBP tag has little impact on the solubility of DUSP14 and TEV protease. The solubility of His-tagged DUSP14 and His-tagged TEV protease is assessed by SDS-PAGE (left) and quantified by densitometry (right, white bars). The % solubility of the C-terminal His-DUSP14-MBP and His-TEV-MBP (gray bars) is duplicated from Figure 2C.

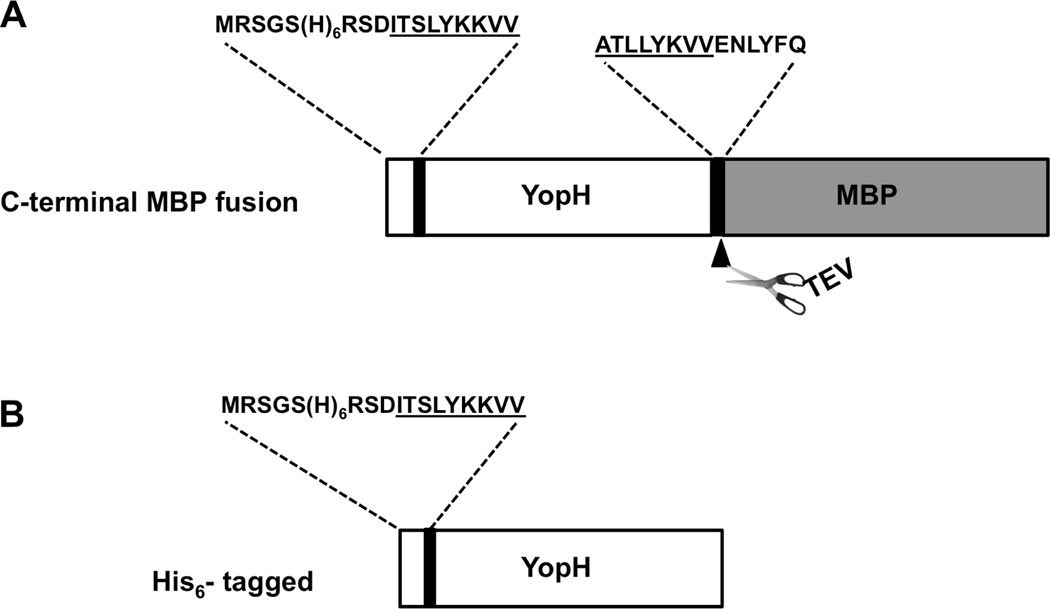

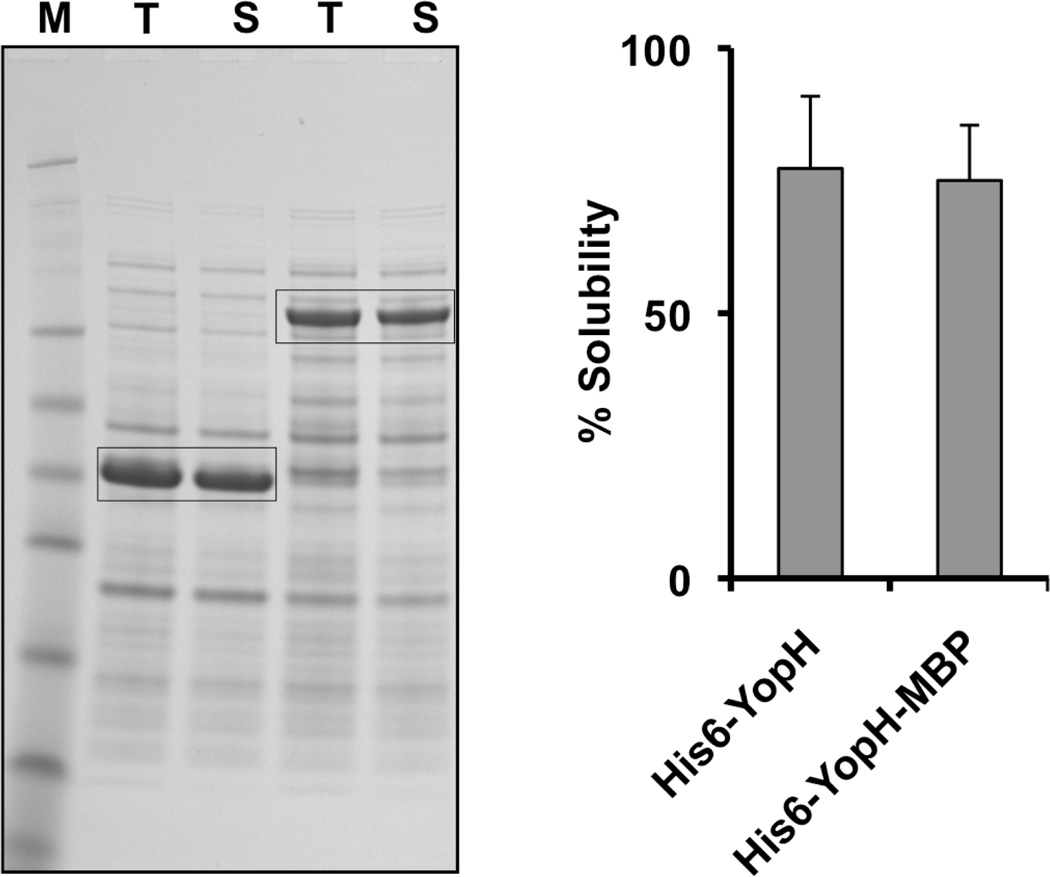

The catalytic domain of Yersinia pestis protein tyrosine phosphatase YopH, which is highly soluble in E. coli [19, 20], was used to test this hypothesis. YopH was produced with just an N-terminal polyhistidine tag and with both an N-terminal polyhistidine tag and a C-terminal MBP tag (Figure 4). Interestingly, here again the fusion protein with MBP attached to its C-terminus was expressed at a lower level than was the protein with no C-terminal MBP tag (Figure 5). However, as expected, the solubility of both forms of YopH was essentially the same. In this case, the longer polyhistidine tag and the presence of the attB3 site instead of attB1 between the YopH and MBP domains did not impede the solubility of YopH, presumably because YopH does not require or benefit from the solubility-enhancing activity of MBP.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation (not to scale) of the His-YopH-MBP and His-YopH constructs. The attB1 and attB3 derived linker residues are underlined. The sequences at the junction, TEV protease cleavage site and His-tag are marked as well. The multi-site gateway components (N-terminal attB1 and interdomain attB3 junction) were retained in these constructs.

Figure 5.

Solubility of YopH variants. The solubility of His-YopH-MBP and His-YopH was assessed by SDS-PAGE (left) and quantified by densitometry (right).

These data contradict the earlier findings of Dyson et al., who reported that MBP is a good solubility enhancer irrespective of which end of the passenger protein it is attached to [13]. There are several possible explanations for this discrepancy. First, their data were reported as mg of soluble protein per liter of culture. However, the C-terminal MBP fusions (i.e., passenger-MBP) described in the Dyson paper were expressed at radically different levels in E. coli, ranging from 0–157 mg/liter, and their method of calculating fusion protein solubility failed to take this into account. Specifically, the amount of soluble protein was not normalized to the total amount of protein expressed to generate a quotient (% soluble). Second, nearly all of the proteins that were scored as soluble when fused to the N-terminus of MBP in their study were also soluble as N-terminally His10-tagged proteins, suggesting that these proteins, like DUSP14, TEV protease and YopH, did not require solubility enhancement by MBP and were therefore indifferent to its presence on their C-termini. Finally, the fact that the inter-domain linker sequences were different in the N- and C-terminal fusion proteins examined by Dyson et al. (attB1 vs. attB2) may have also affected their results, as was observed in the present study (attB3 vs. attB1).

The main conclusion of this study is that MBP provides an excellent solubility-enhancing advantage when joined to the N-termini of a variety of passenger proteins but much less so when fused to their C-termini. This suggests that MBP needs to emerge first from the active ribosome for it to be fully functional as a solubility enhancer and is consistent with a model in which folded MBP binds to partially folded passenger proteins to inhibit their intermolecular aggregation. We also observed a positive impact on the yield of fusion proteins when MBP preceded the passenger protein. Hence, our study illustrates the importance of the positioning of translational fusion partners when goal is to maximize the yield and solubility of recombinant proteins in E. coli.

Highlights.

Both the yield and solubility of aggregation-prone proteins can be improved by fusing them to MBP

N-terminal positioning of MBP in fusion proteins is clearly superior to C-terminal positioning

Even minor alterations of inter-domain linker residues can have a major impact on solubility

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research. Karina Keefe was supported in part by the Werner H Kirsten Student Intern Program (WHK SIP), Office of the Director, NCI-Frederick. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does the mention of trade names, commercial products or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Costa S, Almeida A, Castro A, Domingues L. Fusion tags for protein solubility, purification and immunogenicity in Escherichia coli: the novel Fh8 system. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:63. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esposito D, Chatterjee DK. Enhancement of soluble protein expression through the use of fusion tags. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2006;17:353–358. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hewitt SN, Choi R, Kelley A, Crowther GJ, Napuli AJ, Van Voorhis WC. Expression of proteins in Escherichia coli as fusions with maltose-binding protein to rescue non-expressed targets in a high-throughput protein-expression and purification pipeline. Acta Crystallogr Sect F Struct Biol Cryst Commun. 2011;67:1006–1009. doi: 10.1107/S1744309111022159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kapust RB, Waugh DS. Escherichia coli maltose-binding protein is uncommonly effective at promoting the solubility of polypeptides to which it is fused. Protein Sci. 1999;8:1668–1674. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.8.1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Douette P, Navet R, Gerkens P, Galleni M, Levy D, Sluse FE. Escherichia coli fusion carrier proteins act as solubilizing agents for recombinant uncoupling protein 1 through interactions with GroEL. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:686–693. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox JD, Kapust RB, Waugh DS. Single amino acid substitutions on the surface of Escherichia coli maltose-binding protein can have a profound impact on the solubility of fusion proteins. Protein Sci. 2001;10:622–630. doi: 10.1110/ps.45201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox JD, Routzahn KM, Bucher MH, Waugh DS. Maltodextrin-binding proteins from diverse bacteria and archaea are potent solubility enhancers. FEBS Lett. 2003;537:53–57. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nallamsetty S, Waugh DS. Solubility-enhancing proteins MBP and NusA play a passive role in the folding of their fusion partners. Protein Expr Purif. 2006;45:175–182. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nallamsetty S, Waugh DS. Mutations that alter the equilibrium between open and closed conformations of Escherichia coli maltose-binding protein impede its ability to enhance the solubility of passenger proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;364:639–644. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raran-Kurussi S, Waugh DS. The ability to enhance the solubility of its fusion partners is an intrinsic property of maltose-binding protein but their folding is either spontaneous or chaperone-mediated. PLoS One. 2012;7:e49589. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nomine Y, Ristriani T, Laurent C, Lefevre JF, Weiss E, Trave G. Formation of soluble inclusion bodies by hpv e6 oncoprotein fused to maltose-binding protein. Protein Expr Purif. 2001;23:22–32. doi: 10.1006/prep.2001.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sachdev D, Chirgwin JM. Order of fusions between bacterial and mammalian proteins can determine solubility in Escherichia coli. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1998;244:933–937. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.8365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dyson MR, Shadbolt SP, Vincent KJ, Perera RL, McCafferty J. Production of soluble mammalian proteins in Escherichia coli: identification of protein features that correlate with successful expression. BMC Biotechnol. 2004;4:32. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-4-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lountos GT, Tropea JE, Cherry S, Waugh DS. Overproduction, purification and structure determination of human dual-specificity phosphatase 14. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2009;65:1013–1020. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909023762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kapust RB, Tozser J, Fox JD, Anderson DE, Cherry S, Copeland TD, Waugh DS. Tobacco etch virus protease: mechanism of autolysis and rational design of stable mutants with wild-type catalytic proficiency. Protein Eng. 2001;14:993–1000. doi: 10.1093/protein/14.12.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kapust RB, Tozser J, Copeland TD, Waugh DS. The P1' specificity of tobacco etch virus protease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;294:949–955. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)00574-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nallamsetty S, Austin BP, Penrose KJ, Waugh DS. Gateway vectors for the production of combinatorially-tagged His6-MBP fusion proteins in the cytoplasm and periplasm of Escherichia coli . Protein Sci. 2005;14:2964–2971. doi: 10.1110/ps.051718605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurz M, Cowieson NP, Robin G, Hume DA, Martin JL, Kobe B, Listwan P. Incorporating a TEV cleavage site reduces the solubility of nine recombinant mouse proteins. Protein expression and purification. 2006;50:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phan J, Lee K, Cherry S, Tropea JE, Burke TR, Jr, Waugh DS. High-resolution structure of the Yersinia pestis protein tyrosine phosphatase YopH in complex with a phosphotyrosyl mimetic-containing hexapeptide. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13113–13121. doi: 10.1021/bi030156m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang ZY, Clemens JC, Schubert HL, Stuckey JA, Fischer MW, Hume DM, Saper MA, Dixon JE. Expression, purification, and physicochemical characterization of a recombinant Yersinia protein tyrosine phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:23759–23766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]