SUMMARY

Neurons utilize mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OxPhos) to generate energy essential for survival, function and behavioral output. Unlike most cells that burn both fat and sugar, neurons only burn sugar. Despite its importance, how neurons meet the increased energy demands of complex behaviors such as learning and memory is poorly understood. Here we show that the estrogen related receptor gamma (ERRγ) orchestrates the expression of a distinct neural gene network promoting mitochondrial oxidative metabolism that reflects the extraordinary neuronal dependence on glucose. ERRγ−/− neurons exhibit decreased metabolic capacity. Impairment of long-term potentiation (LTP) in ERRγ−/− hippocampal slices can be fully rescued by the mitochondrial OxPhos substrate pyruvate, functionally linking the ERRγ knockout metabolic phenotype and memory formation. Consistent with this notion, mice lacking neuronal ERRγ in cerebral cortex and hippocampus exhibit defects in spatial learning and memory. These findings implicate neuronal ERRγ in the metabolic adaptations required for memory formation.

INTRODUCTION

Mature neurons have exceedingly high energy demands, requiring a continuous supply of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) for survival, excitability, as well as for the synaptic signaling and circuitry underlying different behaviors. Neurons utilize aerobic metabolism of glucose, but not fat, to meet their fluctuating needs (Escartin et al., 2006; Magistretti, 2003). Indeed, the predominance of pyruvate as the mitochondrial substrate for ATP generation suggests the possibility of a distinct neuronal mitochondrial phenotype. Defects in neuronal metabolism, especially in mitochondrial OxPhos, are associated with aging and diverse human neurological diseases (Lazarov et al., 2010; Mattson et al., 2008; Schon and Przedborski, 2011; Stoll et al., 2011; Wallace, 2005). In addition, neuronal metabolism (especially glucose uptake) and blood flow are tightly coupled with neuronal activity, an adaptation to the increased energy demand from complex tasks such as learning and memory (Howarth et al., 2012; Patel et al., 2004; Shulman et al., 2004). This neurometabolic and neurovascular coupling provides the basis for widely-used brain imaging techniques including functional magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography (Fox et al., 1988; Shulman et al., 2004). However, the molecular underpinnings regulating neuronal metabolism and its link to behavior remain poorly understood. Though such metabolic adaptations are at least partially mediated by transcriptional mechanisms that modulate the expression of metabolic genes (Alberini, 2009; Magistretti, 2006), the key transcription factors involved remain to be identified.

RESULTS

ERRγ is Highly Expressed in Both Developing and Mature Neurons

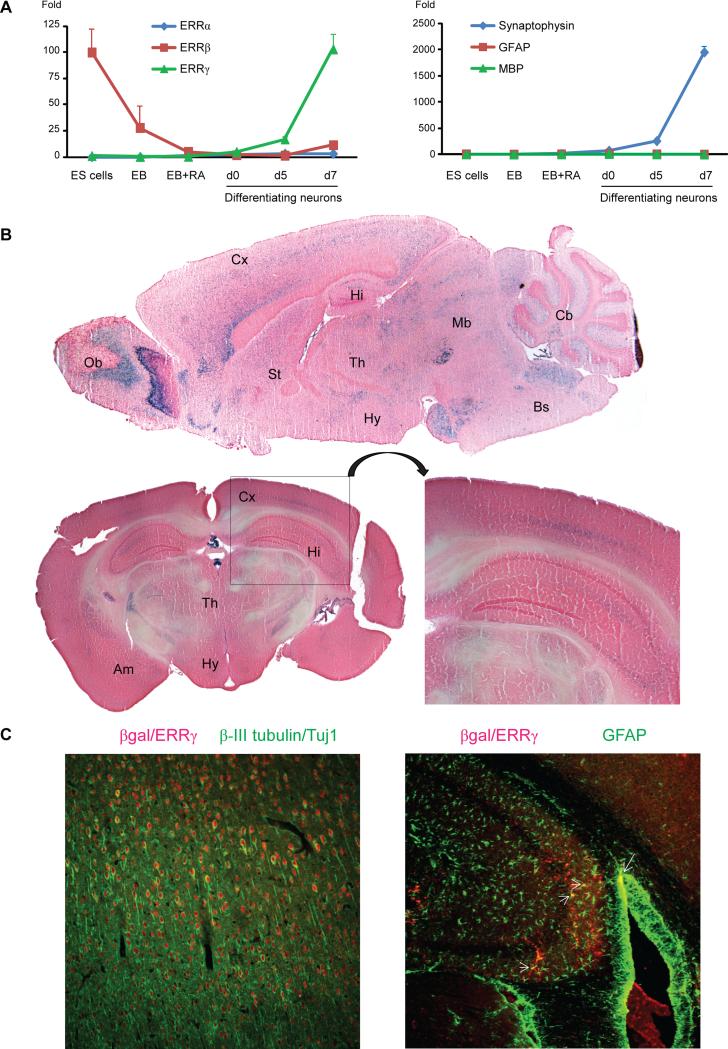

To investigate the global impact of metabolism on neuronal function and behavior, we aimed to identify key transcription factors that regulate metabolism in the neurons. Neuronal differentiation is known to induce mitochondrial biogenesis and OxPhos (Mattson et al., 2008). Therefore we reasoned that key neuronal metabolic regulators would be concordantly induced. We used a well-established protocol to differentiate mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells into neurons with high degree of uniformity (Bibel et al., 2007). We then examined the expression of some transcription factors with established metabolic regulatory function in peripheral tissues based on existing literature. We found that ERRγ was highly induced during neuronal differentiation (Figure 1A). In contrast, ERRα expression was barely changed. ERRβ is highly expressed in ES cells and is one of the key factors for their maintenance (Feng et al., 2009); its expression was decreased during neuronal differentiation. Using a mouse strain where LacZ was inserted into the Esrrg locus, our previous work has shown that ERRγ is highly expressed in the developing embryonic central nervous system in vivo as well (Alaynick et al., 2007). Consistent with previous reports using in situ hybridization (Gofflot et al., 2007; Lorke et al., 2000), X-gal staining revealed that ERRγ protein was abundant and widely expressed in the adult mouse brain, including the olfactory bulb, cerebral cortex, hippocampus, thalamus, hypothalamus, midbrain, striatum, amygdala and brain stem (Figure 1B). For example, many cells in the cerebral cortex, hippocampal CA and dentate gyrus regions expressed ERRγ. Co-immunostaining with different cell type markers suggested that most ERRγ expressing cells in the adult brain were neurons, though it was also expressed in some astrocytes (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. ERRγ is highly expressed in both developing and mature neurons.

(A) Expression of ERRα, ERRβ, ERRγ, neuron marker synaptophysin, astrocyte marker GFAP and oligodendrocyte marker MBP during mouse ES cells differentiation were measured using qRT-PCR. The Y axis indicates fold change of gene expression compared to the ES cells (except for ERRβ where the ES cell level is set as 100). The result is presented as mean + s.e.m.

(B) ERRγ expression pattern in the adult mouse brain was revealed via X-gal staining in 5 month old female ERRγ+/− mice. Part of the cerebrum and hippocampus areas was enlarged for better visualization. Ob – olfactory bulb; Cx – cerebral cortex; Hi – hippocampus; Th – thalamus; Hy – hypothalamus; Mb – midbrain; Cb – cerebellum; St – striatum; Am – amygdala; Bs – brain stem.

(C) Immunostaining of βgal/ERRγ and different cell type markers in 4 month old ERRγ+/− mice cerebrum and hippocampus reveals that ERRγ is expressed in most neurons (indicated by asterisks next to the right side of the cell) and in some astrocytes (arrows). Please note that most neurons are ERRγ positive and only a portion of them are marked by asterisks.

ERRγ regulates neuronal metabolism

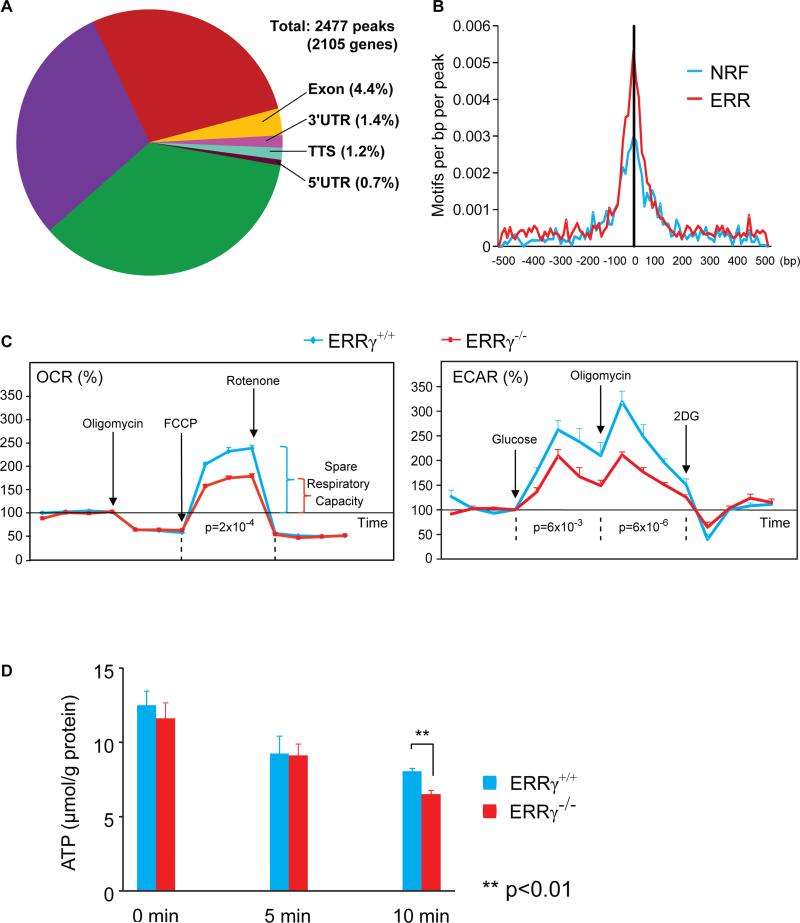

To elucidate a potential role for ERRγ in regulating neuronal metabolism, we used chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by deep sequencing (ChIP-Seq) to map the genome-wide binding sites (cistrome) of ERRγ in neurons. Notably, an unusually high percentage of ERRγ binding sites fell in the promoter regions (~36%), and the locations in intronic and intergenic regions were also significant (~28% and 30%, respectively) (Figure 2A). This tendency of ERRγ to bind to the promoter regions may reflect its preference to associate with certain transcriptional co-factor or chromatin-remodeling complexes. Indeed, sequence motif analysis revealed an extensive colocalization of ERRγ and nuclear respiratory factors (NRFs), established transcriptional regulators of nuclear genes encoding respiratory subunits and components of the mitochondrial transcription and replication machinery (Figures 2B and S1A). Pathway analysis revealed that the most represented pathways were related to ATP generation, especially OxPhos (Figure S1B, Table S1). For example, ChIP-Seq analysis revealed that ERRγ bound to the promoter regions of genes important in transcriptional regulation (Esrra, Gabpa/Nrf2a, etc), glycolysis (Eno1, Gpi1, Pfkm, Ldhβ, etc), TCA cycle (Fh, Idh3a, Ogdh, Sdhβ, etc), OxPhos (Cox5a, Cox6c, Cox8a, Atp5b, etc) and mitochondrial functions (Mrpl39, Tomm40, Slc25a4/Ant1, Mtch2, etc) which were confirmed by conventional ChIP (Figures S1C and S1D). In contrast to previous ChIP-on-Chip studies of ERRγ in the mouse heart (Dufour et al., 2007), the neuronal ERRγ cistrome was depleted of genes involved in fatty acid oxidation, an active process in cardiomyocytes but not in neurons. This indicates a cell-type specific role for ERRγ in regulating cellular metabolism, and supports the notion of an ERRγ-dependent neuronal mitochondrial phenotype. We also used microarray analysis to compare gene expression in the cerebral cortex from newborn wild type (WT) and ERRγ−/− mice; the cerebral cortex comprises a relatively pure neuronal lineage at this stage compared to adult cortex. Among the 1,215 genes that were differentially expressed (p<0.00001), the most significantly represented pathways were related to ATP generation especially OxPhos (Figure S1E), highly overlapping with the ChIP-Seq result (Figure S1B). Importantly, mitochondrial OxPhos activity was significantly decreased in ERRγ−/− mouse cortex, demonstrating the functional importance of ERRγ in supporting neuronal oxidative metabolism (Figure S1F).

Figure 2. ERRγ regulates neuronal metabolism.

(A) Pie chart shows the distribution of genome-wide ERRγ binding sites revealed by ChIP-Seq.

(B) Histogram of motif densities near ERRγ binding sites is shown. ERR and NRF motifs are graphed based on their distances to the center of ERRγ-bound peaks.

(C) OCR and ECAR were measured in WT and ERRγ−/− primary cortical neurons. Values were normalized to the baseline. The result is presented as mean + s.e.m. (n=4). Two-factor with replication ANOVA using data points of each treatment was used to calculate and determine the statistical significance. FCCP: p-trifluorocarbonylcyanide phenylhydrazone; 2DG: 2-Deoxy-D-glucose. Drugs used were: 1 μM oligomycin A, 4 μM FCCP and 2 μM rotenone for OCR; 10 mM glucose, 2 μM oligomycin A and 100 mM 2DG for ECAR. (D) The cellular ATP level in WT and ERRγ−/− primary cortical neurons at different time points after 1μM FCCP treatment was measured and normalized to cellular protein level. The result is presented as mean + s.e.m. (n=4). Two-tail, unpaired, unequal variance t-test was used to calculate and determine the statistical significance. See also Figure S1.

We next investigated whether the loss of ERRγ would affect the metabolic properties of neurons. Cultured primary WT and ERRγ−/− cortical neurons were morphologically similar, established strong synaptic connections (data not shown), and retained comparable protein levels of neuronal markers PSD95 and MAP2 (Figure S1G). Subsequently, their relative rates of oxygen consumption (indicating mitochondrial OxPhos) and extracellular pH change (indicating anaerobic glycolysis) were compared in real time using a Seahorse extracellular flux analyzer. Although WT and ERRγ−/− cortical neurons had comparable basal metabolic rates (data not shown), ERRγ−/− neurons exhibited a significantly reduced maximal and spare oxidative capacity, as determined by use of mitochondrial uncoupler FCCP to stimulate the maximal OxPhos rates (Figures 2C and S1H). ERRγ−/− neurons demonstrated only ~50% of the spare respiratory capacity of WT neurons, suggesting that ERRγ was critical to achieve peak capacity for ATP production. ERRγ−/− neurons also displayed significantly decreased maximal glycolytic capacity when stimulated with glucose or ATP synthase inhibitor oligomycin A (Figure 2C). Accordingly, ERRγ−/− neurons exhibited an impaired ability to maintain their cellular ATP level (Figure 2D). Neither ERRγ+/+ nor ERRγ−/− neurons increased their oxygen uptake in response to palmitate treatment, indicating that neurons’ reliance on glucose but not fat as fuel was ERRγ independent (Figure S1I). In addition, the dependence on ERRγ for maximal metabolic capacity was cell-type specific. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) express both ERRα and ERRγ abundantly; however loss of ERRγ did not affect their total oxidative and glycolytic capacity (Figure S1J).

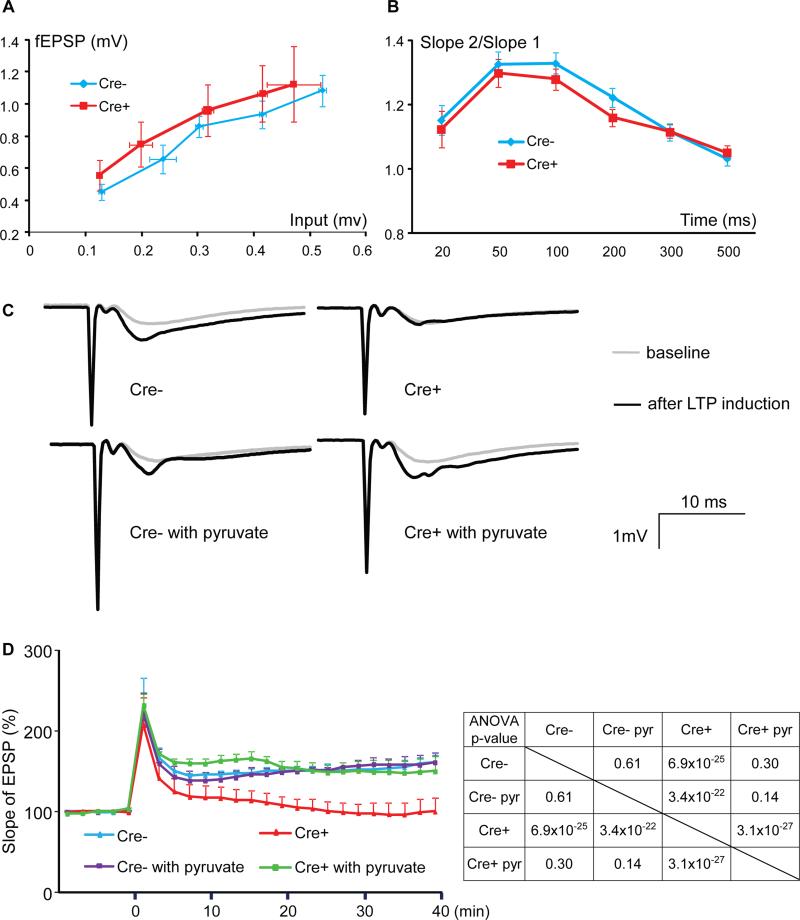

ERRγ deletion significantly impairs hippocampal LTP, which is rescued by mitochondrial OxPhos substrate pyruvate

We next sought to evaluate the in vivo importance of ERRγ-regulated neuronal metabolism in energy demanding brain functions such as learning and memory. Since ERRγ−/− mice die within days of birth (Alaynick et al., 2007), floxed ERRγ alleles were targeted with a late-onset neuron-specific enolase-cre (NSE or Eno2-Cre), to generate mature neuron ERRγ knockout (KO) mice (Figure S2A). Crosses with a Tomato/GFP reporter line (Muzumdar et al., 2007) confirmed that Eno2-Cre yielded a strong, high percentage recombination in cerebral cortex, hippocampus, part of the olfactory bulb, thalamus and brain stem but only sporadically in other brain regions (Figure S2B). By comparing this recombination pattern with the endogenous ERRγ expression pattern (Figure 1B) to subtract non-ERRγ expressing areas, we found that Eno2-Cre resulted in efficient deletion of ERRγ in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus and partial olfactory bulb. ERRγ deficiency in these regions was confirmed by quantifying both the mRNA and nuclear protein levels of ERRγ (Figure S2C). The residual ERRγ may be due to incomplete neuronal deletion or because ERRγ is also expressed in non-neuronal cells (Figure 1C). These neuronal ERRγ KO mice were born in a Mendelian ratio and appeared grossly normal. Both male and female mice had body weights similar to Cre- controls (Figure S2D). We evaluated their brain morphology via Nissl staining. Detailed comparison of the coronal sections at different planes revealed normal histology. In particular, all the structural features and nuclei were present and microscopically normal (Figure S2E). Electron microscopy revealed that neuronal ERRγ KO mouse hippocampi possessed normal subcellular structure, mitochondrial morphology and synaptic vesicles (Figure S2F and data not shown), and no significant differences were seen in the levels of the neurotransmitter glutamate across several brain regions (Figure S2G). Most importantly, the neuronal ERRγ KO mouse hippocampi exhibited normal baseline electrophysiological properties as measured by input-output function and paired pulse ratio (PPR, Figures 3A and 3B), suggesting that the basal hippocampal synaptic transmission and circuits were functional and not affected by loss of ERRγ.

Figure 3. ERRγ deletion significantly impairs hippocampal LTP, which is rescued by mitochondrial OxPhos substrate pyruvate.

(A and B) Input-output function (A) and PPR (B) were measured in 5 – 6 month old Cre- and Cre+ mouse hippocampal slices. The result is presented as mean ± s.e.m.

(C) Sample traces of 5 – 6 month old Cre- and Cre+ mouse hippocampal CA1 LTP with or without 2.5 mM pyruvate.

(D) Cre- and Cre+ mouse hippocampal CA1 LTP (slope of fEPSP) with or without 2.5 mM pyruvate. The result is presented as mean + s.e.m. (n=6). Two-factor with replication ANOVA was used to calculate and determine the statistical significance. P value from ANOVA is shown in the insert table. See also Figure S2.

LTP is well-established as a key neuronal mechanism that underlies learning and memory (Bliss and Collingridge, 1993; Kelleher et al., 2004). The ability of neurons to appropriately enhance synaptic transmission through a memory generating experience depends upon an abundant energy source for ATP-dependent action potentials as well as cycles of neurotransmitter synthesis, release, reuptake and recycling (Belanger et al., 2011). We therefore next recorded hippocampal CA1 LTP (field excitatory post-synaptic potential, fEPSP) in brain slices from these mice. The baseline response was comparable between control and neuronal ERRγ KO mice, again suggesting intact neuronal connections and excitability. However, there was a significant reduction of CA1 LTP in the neuronal ERRγ KO mice (Figures 3C and 3D). In fact, these mice exhibited LTP barely above baseline after stimulation. To determine whether the observed defect in LTP was caused by a metabolic deficiency, we supplemented the hippocampal slices with pyruvate, a well-known energy source and mitochondrial OxPhos substrate, during LTP measurements. Addition of pyruvate should increase the metabolic flux rate of OxPhos and therefore enhance ATP generation. Remarkably, pyruvate supplementation completely rescued the LTP defects in neuronal ERRγ KO but had no effect on control hippocampal slices (Figures 3C and 3D), establishing a causal link between the metabolic deficiency and the LTP defects.

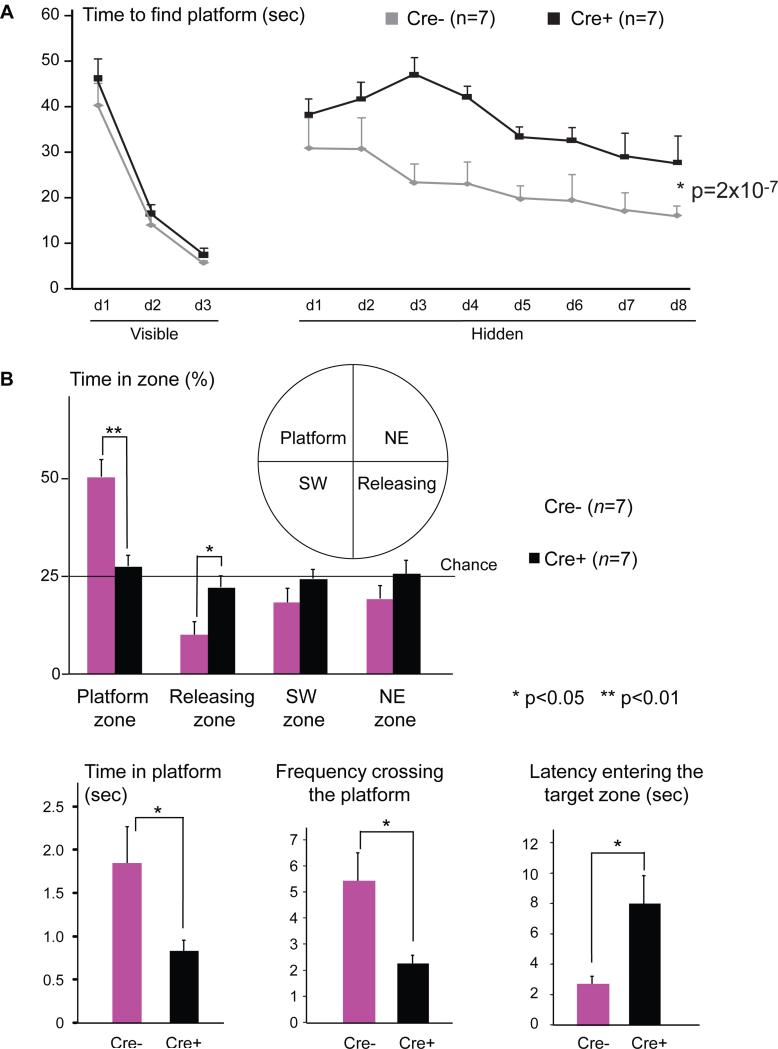

Loss of neuronal ERRγ in vivo impairs spatial learning and memory

We next investigated whether loss of cortical and hippocampal neuronal ERRγ impacted in vivo animal behavior, in particular, hippocampal-dependent spatial learning and memory. As ERRγexpression appeared intact in most other brain regions, we did not expect that the behaviorsheavily dependent on other brain areas would be affected. The functional Observational Battery(Crawley, 2000) showed normal sensory perception, motor control and reflexes. Metabolic cagestudies revealed a normal circadian pattern of movement (Figure S3A) and normal respiratoryexchange ratio (RER, Figure S3B). Furthermore, a series of behavioral tests revealed that the neuronal ERRγ KO mice had normal vision (visual cliff test, data not shown), motorcoordination and balance (rotarod test, Figure S3C), exploratory activity (open field test, Figure S3D) and anxiety (light/dark box test, Figure S3E; and elevated plus maze test, Figure S3F). In sharp contrast, these mice exhibited severe defects in spatial learning and memory in the Morris water maze test compared to control Cre- mice (Figures 4A, 4B and S3G). Although they had no problem locating a visible platform in the Morris water maze indicating normal vision and swimming ability, they were significantly slower in learning to locate the hidden platform (Figure 4A). They also exhibited significantly poorer memory in the probe test to locate the original position of the removed platform (less time spent swimming in the platform zone, less frequency crossing the platform, and longer latency to first enter the target zone; Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Loss of neuronal ERRγ in vivo impairs spatial learning and memory.

(A) The learning curves of 4 month old Cre- and Cre+ mice in finding visual or hidden platform in the Morris water maze test. The result is presented as mean + s.e.m. Two-factor with replication ANOVA was used to calculate and determine the statistical significance.

(B) Spatial memory was evaluated using a probe test in the Morris water maze. Time spent in different zones/platform, frequency crossing the platform and the latency in entering the target zone are shown. The result is presented as mean + s.e.m. Two-tail, unpaired, unequal variance t-test was used to calculate and determine the statistical significance. See also Figure S3.

DISCUSSION

Our studies here identify an essential role for ERRγ in the regulation of neuronal metabolism required for spatial learning and memory. Mechanistically, we identify an ERRγ genomic signature in neurons consistent with their utilization of glucose, but not fat, in mitochondrial OxPhos and energy generation. This neuronal ERRγ genomic signature, combined with the marked reduction in spare respiratory capacity of neurons lacking ERRγ, suggest that persistent synaptic changes associated with memory formation may be limited by insufficient energy in neuronal ERRγ KO mice. Indeed, the finding that LTP defects in neuronal ERRγ KO hippocampus were rescued by pyruvate supplementation supports a role for ERRγ in regulating neuronal metabolism. Consistent with this notion, mice lacking neuronal ERRγ exhibited defects in spatial learning and memory. As ERRγ activity can be modulated with small molecules, targeting ERRγ-dependent neuronal metabolic pathways could provide new therapeutic avenues in the clinical treatment of a variety of neurological diseases.

In addition to ERRγ, closely related proteins ERRα and ERRβ have been shown as important transcriptional regulators of cellular metabolism in peripheral tissues. The three ERR proteins clearly have non-overlapping functions since the individual ERR KO mouse exhibits different phenotypes (Alaynick et al., 2007; Luo et al., 1997; Luo et al., 2003). On the other hand they bind to overlapping loci in the genome, as illustrated in the mouse heart for ERRα and ERRγ (Dufour et al., 2007). Our current and previous studies as well as data from the Allen Brain Atlas indicate that all three ERR proteins are expressed in the brain, but with distinct time and spatial patterns (Gofflot et al., 2007; Lorke et al., 2000; Real et al., 2008). For example, ERRβ is primarily expressed in the developing brain and ERRα expression pattern in the adult brain is more ubiquitous compared to ERRβ and ERRγ. This is significant because different brain cell types (neurons, astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, etc), same cell types in different brain regions and during different developmental stages exhibit diverse metabolic properties (Funfschilling et al., 2012; Goyal et al., 2014; Vilchez et al., 2007). It remains poorly understood regarding the nature and importance of these differences and how such differential metabolic regulation is achieved. Our current study reveals that ERRγ is essential for metabolism and learning/memory of the mature neurons in the hippocampus. Future studies are needed to determine whether the three ERR proteins regulate distinct cellular metabolism, functions and related behaviors in different cell types, brain regions and developmental stages.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Animal experiments

All animal procedures were approved by and carried out under the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the Salk Institute and the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. All mice were maintained in a temperature and light-controlled (6am – 6pm light) environment and received a standard diet (PMI laboratory rodent diet 5001, Harlan Teklad) unless otherwise noted. ERRγ KO mice were previously described (Alaynick et al., 2007) and heterozygous mice were backcrossed to C57BL6/J background for at least 10 generations. The ERRγ floxed and conditional KO strains were backcrossed to C57BL6/J background for at least 6 generations. Age and gender matched mice were used for all experiments.

Gene expression and protein analysis

RNA isolation, gene expression analysis by qRT-PCR and western blot were performed as previously described (Pei et al., 2006).

Histology, immunofluorescence and X-gal staining

Histological analysis and immunofluorescence were performed as previously described (Pei et al., 2011).

Isolation and culture of mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs)

The isolation and culture of MEFs were performed as previously described (Pei et al., 2011). MEFs within 3 generations of culture were used for the experiments.

Extracellular flux (XF) analysis

We analyzed the bioenergetic profiles of ERRγ WT and KO cells using XF24 extracellular flux analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience) following manufacturer's protocol.

Generation of ES cell-derived neurons

We obtained the mouse embryonic stem cell line ES-D3 from ATCC. We followed a previously published protocol (Bibel et al., 2007) to differentiate ES-D3 cells into homogeneous populations of glutamatergic neurons.

ChIP-Seq

We fixed ES cell-derived neurons and performed ChIP-Seq as previously described (Pei et al., 2011).

Microarray Analysis

RNA from WT and ERRγ KO P0 cortex (technical duplicates of 4 cortices each genotype) were extracted and their purity was assessed by Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100. Microarray was performed as previously described (Pei et al., 2011).

Neurotransmitter analysis

Different brain regions were carefully dissected from 5 month old control (Cre-) and neuronal ERRγ KO (Cre+) littermates, weighed, and then grinded and lysed in hypotonic buffer containing proteinase inhibitors (Roche). Glutamate level in the lysates of individual samples was measured using a Sigma kit following manufacturer's instructions and normalized to the sample weight.

Mitochondrial enzyme activity

WT and ERRγ KO P0 littermate mouse cortices were dissected, weighed and homogenized in 20 volume (v/w) of homogenization buffer (1 mM EDTA and 50 mM Triethanolamine in water) on ice. Complex III (Q-cytochrome c oxidoreductase) and Complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) enzymatic activities were determined by the change in absorbance of cytochrome c measured at 550 nm. Assays were performed in 96 well plates with the “Kinetic” function of a SpectraMax Paradigm Multi-Mode Microplate Detection Platform (Molecular Devices). The linear slopes (ΔOD/min) were calculated. The enzymatic activity was determined by the slope (ΔOD/min)/cortex weight (mg)/molar extinction coefficient (OD/mmol/cm)/0.625 cm. The molar extinction coefficient for cytochrome c used was 29.5 OD/mmol/cm.

Electrophysiology

Electrophysiology studies were performed using 5 – 6 month old control and neuronal ERRγ KO littermates as previously described with slight modification (Mu et al., 2011).

Behavior tests

All behavior tests were performed between 1 – 6 pm unless otherwise noted. We conducted metabolic and behavioral studies in mice without prior drug administration or surgery in the following order: metabolic cages, rotarod, open field, light/dark box, elevated plus maze, and Morris water maze. We started the test with 2 – 4 month old mice; they reached 5 – 6 months of age when the Morris water maze test was completed. All tests were repeated in 2 – 3 separate cohorts of mice and similar results were observed. All behavioral studies were repeated by more than one investigator to assure the reproducibility.

Statistical analysis

Two-tail, unpaired, unequal variance t-test or two-factor with replication ANOVA (Microsoft Excel) were used to calculate and determine the statistical significance, with the criterion for significance set at p<0.05. All figure error bars indicate s.e.m.

Please see the Supplemental Information for detailed experimental procedures.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank C. McDonald, M. Karunasiri, H. Juguilon, S. Andrews, M. Joens, and J. Fitzpatrick for technical and EM studies support; D. Wallace, A. Atkins, C. Perez-Garcia, R. Carney, W. Fan, J. Whyte, O. Chivatakarn, A. Levine, K. Hilde, T. Wang, R. Hernandez, Y. Kim, and M. Marchetto for helpful discussions; Z. Zhou for the PSD95 antibody; and E. Ong, C. Brondos, and S. Ganley for administrative assistance. R.M.E. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies and March of Dimes Chair in Molecular and Developmental Biology. This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute; NIH grants DK057978, HL105278, DK090962, and CA014195 (R.M.E.); NIMH MH090258 (F.H.G.); the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust Grant (R.M.E & F.H.G); Ellison Medical Foundation and Glenn Foundation for Medical Research (R.M.E.); the G. Harold & Leila Y. Mathers Charitable Foundation, the JPB Foundation, and Annette Merrill-Smith (F.H.G); pilot funds from the Research Institute of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), CHOP Metabolism, Nutrition and Development Research Affinity Group Pilot Grant, and Penn Medicine Neuroscience Center (PMNC) Innovative Pilot Funding Program (L.P.). L.P. conceived of the project and designed and performed most of the experiments. Y.M. performed the hippocampal LTP recordings and analyzed the data together with L.P. M.L. is a pathologist who evaluated the histology and staining results. W.A. performed some of the X-gal staining and immunostaining experiments. R.T.Y. and C.L. analyzed the ChIP-Seq and microarray data. G.D.B., M.P., T.W.T., S.K., M.D., S.L.P., and J.A. provided technical assistance, research materials, or intellectual input. R.M.E. supervised the project. L.P. and R.M.E. wrote, and F.H.G., M.D., and R.T.Y. reviewed and edited, the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information includes Supplemental Experimental Procedures, three Supplemental Figures and two Supplemental Tables.

L.P., R.T.Y., M.D., and R.M.E. are coinventors of a method of modulating hippocampal function and may be entitled to royalties.

REFERENCES

- Alaynick WA, Kondo RP, Xie W, He W, Dufour CR, Downes M, Jonker JW, Giles W, Naviaux RK, Giguere V, et al. ERRgamma directs and maintains the transition to oxidative metabolism in the postnatal heart. Cell Metab. 2007;6:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberini CM. Transcription factors in long-term memory and synaptic plasticity. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:121–145. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00017.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belanger M, Allaman I, Magistretti PJ. Brain energy metabolism: focus on astrocyte-neuron metabolic cooperation. Cell Metab. 2011;14:724–738. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibel M, Richter J, Lacroix E, Barde YA. Generation of a defined and uniform population of CNS progenitors and neurons from mouse embryonic stem cells. Nature protocols. 2007;2:1034–1043. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TV, Collingridge GL. A synaptic model of memory: long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Nature. 1993;361:31–39. doi: 10.1038/361031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawley JN. What's wrong with my mouse? : behavioral phenotyping of transgenic and knockout mice. Wiley-Liss; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dufour CR, Wilson BJ, Huss JM, Kelly DP, Alaynick WA, Downes M, Evans RM, Blanchette M, Giguere V. Genome-wide orchestration of cardiac functions by the orphan nuclear receptors ERRalpha and gamma. Cell Metab. 2007;5:345–356. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escartin C, Valette J, Lebon V, Bonvento G. Neuron-astrocyte interactions in the regulation of brain energy metabolism: a focus on NMR spectroscopy. J Neurochem. 2006;99:393–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng B, Jiang J, Kraus P, Ng JH, Heng JC, Chan YS, Yaw LP, Zhang W, Loh YH, Han J, et al. Reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced pluripotent stem cells with orphan nuclear receptor Esrrb. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:197–203. doi: 10.1038/ncb1827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox PT, Raichle ME, Mintun MA, Dence C. Nonoxidative glucose consumption during focal physiologic neural activity. Science. 1988;241:462–464. doi: 10.1126/science.3260686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funfschilling U, Supplie LM, Mahad D, Boretius S, Saab AS, Edgar J, Brinkmann BG, Kassmann CM, Tzvetanova ID, Mobius W, et al. Glycolytic oligodendrocytes maintain myelin and long-term axonal integrity. Nature. 2012;485:517–521. doi: 10.1038/nature11007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gofflot F, Chartoire N, Vasseur L, Heikkinen S, Dembele D, Le Merrer J, Auwerx J. Systematic gene expression mapping clusters nuclear receptors according to their function in the brain. Cell. 2007;131:405–418. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal MS, Hawrylycz M, Miller JA, Snyder AZ, Raichle ME. Aerobic glycolysis in the human brain is associated with development and neotenous gene expression. Cell Metab. 2014;19:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howarth C, Gleeson P, Attwell D. Updated energy budgets for neural computation in the neocortex and cerebellum. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1222–1232. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher RJ, 3rd, Govindarajan A, Tonegawa S. Translational regulatory mechanisms in persistent forms of synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2004;44:59–73. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarov O, Mattson MP, Peterson DA, Pimplikar SW, van Praag H. When neurogenesis encounters aging and disease. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:569–579. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorke DE, Susens U, Borgmeyer U, Hermans-Borgmeyer I. Differential expression of the estrogen receptor-related receptor gamma in the mouse brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2000;77:277–280. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Sladek R, Bader JA, Matthyssen A, Rossant J, Giguere V. Placental abnormalities in mouse embryos lacking the orphan nuclear receptor ERR-beta. Nature. 1997;388:778–782. doi: 10.1038/42022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, Sladek R, Carrier J, Bader JA, Richard D, Giguere V. Reduced fat mass in mice lacking orphan nuclear receptor estrogen-related receptor alpha. Molecular and cellular biology. 2003;23:7947–7956. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.22.7947-7956.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magistretti P. Fundamental Neuroscience. 2nd edition Academic Press; New York: 2003. Brain energy metabolism. pp. 339–360. [Google Scholar]

- Magistretti PJ. Neuron-glia metabolic coupling and plasticity. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:2304–2311. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP, Gleichmann M, Cheng A. Mitochondria in neuroplasticity and neurological disorders. Neuron. 2008;60:748–766. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu Y, Zhao C, Gage FH. Dopaminergic modulation of cortical inputs during maturation of adult-born dentate granule cells. J Neurosci. 2011;31:4113–4123. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4913-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzumdar MD, Tasic B, Miyamichi K, Li L, Luo L. A global double-fluorescent Cre reporter mouse. Genesis. 2007;45:593–605. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel AB, de Graaf RA, Mason GF, Kanamatsu T, Rothman DL, Shulman RG, Behar KL. Glutamatergic neurotransmission and neuronal glucose oxidation are coupled during intense neuronal activation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:972–985. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000126234.16188.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei L, Leblanc M, Barish G, Atkins A, Nofsinger R, Whyte J, Gold D, He M, Kawamura K, Li HR, et al. Thyroid hormone receptor repression is linked to type I pneumocyte-associated respiratory distress syndrome. Nat Med. 2011;17:1466–1472. doi: 10.1038/nm.2450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei L, Waki H, Vaitheesvaran B, Wilpitz DC, Kurland IJ, Tontonoz P. NR4A orphan nuclear receptors are transcriptional regulators of hepatic glucose metabolism. Nat Med. 2006;12:1048–1055. doi: 10.1038/nm1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Real MA, Heredia R, Davila JC, Guirado S. Efferent retinal projections visualized by immunohistochemical detection of the estrogen-related receptor beta in the postnatal and adult mouse brain. Neurosci Lett. 2008;438:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schon EA, Przedborski S. Mitochondria: the next (neurode)generation. Neuron. 2011;70:1033–1053. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman RG, Rothman DL, Behar KL, Hyder F. Energetic basis of brain activity: implications for neuroimaging. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:489–495. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoll EA, Cheung W, Mikheev AM, Sweet IR, Bielas JH, Zhang J, Rostomily RC, Horner PJ. Aging neural progenitor cells have decreased mitochondrial content and lower oxidative metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:38592–38601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.252171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilchez D, Ros S, Cifuentes D, Pujadas L, Valles J, Garcia-Fojeda B, Criado-Garcia O, Fernandez-Sanchez E, Medrano-Fernandez I, Dominguez J, et al. Mechanism suppressing glycogen synthesis in neurons and its demise in progressive myoclonus epilepsy. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1407–1413. doi: 10.1038/nn1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace DC. A mitochondrial paradigm of metabolic and degenerative diseases, aging, and cancer: a dawn for evolutionary medicine. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:359–407. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.110304.095751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.