Abstract

Ovarian cancer is a dreadful disease estimated to be the second most common gynecological malignancy worldwide. Its current therapy, based on cytoreductive surgery followed by the combination of platinum and taxanes, is frequently complicated by the onset of multidrug resistance (MDR). The discovery that survivin, a small anti-apoptotic protein, is involved in chemo-resistance, provided a new prospect to overcome MDR in cancer, since siRNA could be used to inhibit the expression of survivin in cancer cells. With this in mind, we have developed self-assembly polymeric micelles (PM) able to efficiently co-load an anti-survivin siRNA and a chemotherapeutic agent, such as Paclitaxel (PXL) (survivin siRNA/PXL PM). Previously, we have successfully demonstrated that the down-regulation of survivin by using siRNA-containing PM strongly sensitizes different cancer cells to PXL. Here, we have evaluated the applicability of the developed multifunctional PM in vivo. Changes in survivin expression, therapeutic efficacy and biological effects of the nanopreparation were investigated in an animal model of PXL-resistant ovarian cancer. The results obtained in mice xenografed with SKOV3-tr revealed a significant down-regulation of survivin expression in tumor tissues together with a potent anticancer activity of survivin siRNA/PXL PM, while the tumors remained unaffected with the same quantity of free PXL alone. These promising results introduce a novel type of non-toxic and easy-to-obtain nano-device for the combined therapy of siRNA and anti-cancer agents in the treatment of chemo-resistant tumors.

Keywords: Multifunctional Polymeric Micelles, Anti-survivin siRNA, Paclitaxel, Self-assembly, Drug-resistant ovarian cancer

Introduction

Ovarian cancer, the most deadly gynecologic malignancies, is often diagnosed at late stages (1). The current therapy of advanced ovarian carcinomas consists on platinum and PXL-based combination chemotherapy (2). However, invariably, after an unpredictable time of response to therapy, a significant percentage of patients undergo to a resistant phase. Recently, a correlation between chemo-resistance and expression of survivin in cancer has been reported (3). Survivin is a small anti-apoptotic protein expressed only in embryonal and fetal tissues (4). However, high survivin levels have been detected in many cancer tissues (5), especially in advanced stages. The over-expression of survivin has been associated with poor prognosis and aggressiveness of the tumors (6). In advanced ovarian carcinomas, it has been found that the expression of survivin directly correlates with a clinical resistance to taxane chemotherapy (7). The treatments that suppress survivin expression can induce apoptosis, inhibit cancer growth, and enhance the sensitivity of cancer cells to chemotherapy and radiotherapy (8). From here, new strategies based on the inhibition of survivin in tumor tissues should represent a powerful tool to enhance the chemo-sensitivity in patients with drug-resistance ovarian cancer.

The use of small interfering RNA (siRNA) offers a valid and efficient approaches to selectively inhibit the expression of survivin in vitro (9). Since the unfavorable pharmacokinetic profile of the siRNA hampers its direct use in the clinic, earlier we have designed stable nanopreparations of siRNA. In particular, we have developed and characterized polyethyelene glycol2000-phosphatidyl ethanolamine (PEG2000-PE)-based polymeric micelles (PM) containing an anti-survivin siRNA reversibly conjugated with phospholipid (phosphatidylethanolamine, PE) via a disulfide linkage (survivin siRNA-S-S-PE) (10, 11). This chemical conjugation was designed to increase the stability of the siRNA in biological fluids and allow for siRNA liberation in free form in cancer cells due to the reduction of the disulfide bond with high concentration of intracellular glutathione. We found an effective stabilization of the modified siRNA in PM against nucleolytic degradation in vitro (10). In addition, the incorporation of the modified survivin siRNA-S-S-PE into PEG2000-PE-based PM allowed to efficiently deliver the siRNA in the cells. As a result, in different cancer cell lines, a significant down-regulation of survivin protein expression and a decrease in the cell viability were observed (11).

Then, we attempted combining anti-survivin siRNA and PXL within one multifunctional nano-assembly by encapsulating both into PM to achieve a better anti-cancer effect of the two agents for the treatment of aggressive ovarian cancer. Clear evidences are given by pre-clinical and early clinical trials that the combined delivery of siRNA and chemotherapeutic agents within one nanoparticulated system are indeed more efficient in inhibiting the tumor growth and overcoming the drug resistance compared to nanoparticles containing single agents (12). In our preliminary study, survivin siRNA/PXL PM effectively co-encapsulated chemotherapeutic agent and siRNA and showed high cytotoxicity against SKOV3-tr cell line (11). In the present manuscript, we have investigated the in vivo therapeutic potential of the developed survivin siRNA/PXL PM in mice with xenografts of PXL-resistant ovarian carcinoma, SKOV3-tr. We have also investigated the down-regulation of survivin synthesis in tumor cells and the biochemical effects of the formulation.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Unless otherwise stated, all chemicals were from Sigma-Aldrich (Saint Louis, MO). Survivin siRNA 5’-GCAUUCGUCCGGUUGCGCUdTdT-3’ and a scrambled siRNA 5’-AUGAACUUCAGGGUCAGCUdTdT-3’ have been used. Both siRNAs modified at the 3′-end of the sense strand with N-succinimidyl 3-(2-pyridyldithio)propionate (SPDP) group were purchased from Thermo Scientific Dharmacon (Pittsburgh PA, USA). Paclitaxel (PXL) was purchased from LC Laboratories (Woburn MA, United States). The PXL Oregon green (P22310) was from Invitrogen, CA. The 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphothioethanol (PE-SH, MW 731) and 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-{methoxy[poly(ethyleneglycol)]-2000} (PEG2000-PE) were from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). The RNeasy kit for mRNA isolation was obtained from Qiagen (Germantown, MD). The First Strand cDNA synthesis kit and the SYBR green kit for qRT-PCR were purchased from Roche, USA. Primers for the survivin gene (5’CTGCCTGGCAGCCCTTT-3’) and (5’CCTCCAGAAGGGCCA-3’) and for β-actin were obtained from Invitrogen, CA. The Aspartate aminotransferase (AST)/Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) assay kit was purchased from the biomedical research service center at SUNY Buffalo (Buffalo, NY). The rabbit anti-survivin antibody, AF886, was from R&D System (Minneapolis, MN). β-Tubulin antibody (G-8) was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, Texas, USA). Texas red-x goat anti-rabbit IgG (T6391) and Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse IgG, IgA, IgM (H+L) were from Life Technologies (Eugene, Oregon, USA). Hoechst 33342 trihydrochloride, trihydrate, was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, Oregon, USA). Vecta Shield mounting medium for fluorescence, H-1000, was from Vector Laboratories, Inc. (Burlingame, CA). DeadEnd™ Fluorometric TUNEL System from Promega Corporation (Madison, WI).

Preparation and characterization of PM co-encapsulating survivin siRNA and PXL

The survivin siRNA-S−S-PE conjugate was synthesized as described earlier (11). The PEG2000-PE micelles containing survivin siRNA-S-S-PE and PXL were prepared as reported previously, with slight modifications for the in vivo translation (11). Briefly, an organic solution of PXL in methanol (1 mg/mL) was added to the PEG2000-PE solution (60 mg/mL) in chloroform. The initial quantity of PXL relative to the main micelle-forming component was 2% w/w. The resulting solution was added to a 50 ml round-bottom flask, and the organic solvent was removed under the reduced pressure on a rotary evaporator under the nitrogen, followed by freeze-drying. Then, the polymeric film formed was hydrated with 1 mL of the solution of survivin siRNA-S-S-PE in PBS at pH 7.4 at PEG2000-PE/siRNA-S-S-PE weight ratio of 600:1. The resulting dispersion was gently vortexed to form mixed survivin siRNA/PXL PM. PEG2000-PE-based PM containing survivin siRNA-S-S-PE alone and scrambled siRNA-S-S-PE in combination with PXL were prepared similarly. Each formulation was prepared in triplicate. For intra-tumor accumulation studies, survivin siRNA/PXL PM containing 0.1% (w/w) of Oregon Green-labeled PXL were prepared similarly.

Characterization of survivin siRNA/PXL PM

The mean diameter of PM containing survivin siRNA-S-S-PE in combination with PXL, was determined at 20°C by the dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a Zeta Plus Instrument (Brookhaven Instrument Co., Holtsville, NY). Briefly, each sample was diluted in deionized/filtered water and analyzed with detector at the 90° angle. As a measure of the particle size distribution, polydispersity index (P.I.) was used. For each batch, mean diameter and size distribution were the mean of three measurements. For each formulation, the mean diameter and P.I. were calculated as the mean of three different batches. The quantitative analysis of survivin siRNA-S-S-PE and PXL content in PM was performed by the size-exclusion high-performance liquid chromatography (SEC-HPLC) and RP-HPLC, respectively, as reported previously by Salzano G et al. (11).

Cell Culture

Human ovarian adenocarcinoma resistant cell line, SKOV3-tr PXL resistant cells, were kindly provided and tested by Dr. Zhenfeng Duan at the Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA) immediately before the in vivo study. The phenotype of SKOV3-tr has been deeply characterized by Dr. Duan Z. and co-workers by high-density Affymetrix HG-U95Av2 microarrays to quantify the gene expression (13). In detail, SKOV3 cells, obtained from ATCC (Rockville, Md.), were selected to be PXL resistant by continuous exposure of cells with increasing concentration of PXL for eight months. A significant and stable over-expression of the MDR-1 gene, associated with acquired PXL resistance, was identified. In addition, the PXL resistant phenotype and the MDR-1 expression did not changed when the SKOV3-tr cells were grown for six months without PXL. In our lab, we have routinely monitored the IC(50) of PXL in SKOV3-tr by Cell Titer Blue assay (CTB). CTB assay showed that SKOV3-tr were at least 100-fold more resistant than the sensitive SKOV3 cell line.

SKOV3-tr cells were grown in RPMI®-1640 medium supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 100 U/mL penicillin G sodium and 100 mg/mL streptomycin sulfate (complete medium), in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air 5% CO2 at 37 °C. For the subculture, cells growing as a monolayer were detached from the tissue flasks by the treatment with trypsin/EDTA. The viability and cell count were monitored routinely using the Trypan blue dye exclusion method. The cells were harvested during the logarithmic growth phase and re-suspended in serum free medium before inoculation in animals.

In vivo studies

Experimental model

The experimental protocol involving the use of animals was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Northeastern University. SCID female nude mice (nu/nu), 6–8 weeks old and weighing 20–25 g were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Cambridge, MA), and were housed under controlled laboratory conditions in polycarbonate cages. The animals were allowed to acclimate for at least 48 hr before any experiment.

Subcutaneous tumor xenografts development

Approximately 7 million of SKOV3-tr cells, suspended in 100 µl of Matrigel® (in free serum media 1:1 volume ratio), were injected subcutaneously in the left flank of each mouse under light isoflurane anesthesia. Palpable solid tumors developed within 15 days post tumor cell inoculation, and as soon as tumor volume reached 150–200 mm3, the animals were randomly allocated to 5 different control and treatment groups [i.e., PBS, PXL in Cremophor EL1-ethanol (1:1) mixture with normal saline (Taxol), PM containing scrambled siRNA-S-S-PE conjugate and PXL in combination (scrambled siRNA/PXL PM), PM containing survivin siRNA-S-S-PE conjugate (survivin siRNA PM) and PM containing survivin siRNA-S-S-PE and PXL in combination (survivin siRNA/PXL PM). Six animals per group were used. All controls and micelle formulations were diluted and suspended in sterile PBS. Each tumor-bearing animal received siRNA-S-S-PE at a dose of 20 µg, corresponding to 1mg/kg per injection, and PXL at a dose 10 mg/kg both in Cremophor solution or in PM by intravenous administration through the tail vein once per week for 5 consecutive weeks.

Evaluation of therapeutic efficacy

The tumor diameters were measured three times weekly with a vernier calipers in two dimensions. Individual tumor volumes (V) were calculated using the formula (14):

V = [length × (width)2]/2

where length (L) is the longest diameter and width (W) is the shortest diameter perpendicular to length.

Growth curves for tumors are presented as the Relative Tumor Volume (RTV), defined as Vn/Vo, where Vn was the tumor volume in mm3 on day ‘n’ (Vn) and Vo at the start of the treatment plotted versus time in days. Mean RTV (mRTV) and standard deviation were calculated per each group. At the end of the experiment, the animals were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and the tumor mass was harvested and weighed.

Evaluation of repeated dose toxicity in mice

For safety evaluation of the controls and survivin siRNA/PXL PM formulation, the body weight of each mouse was determined three times per week and related to the first day weight as percent change in body weight. In addition, blood samples were collected via the cardiac puncture prior to the sacrifice, and the levels of serum aspartate amino transferase (AST) and alanine amino transferase (ALT) were measured. The serum was obtained by centrifugation of the freshly collected blood samples at 2,000×g for 30 min at 4°C. Then, AST and ALT were measured using the manufacturer’s standard kinetic assay protocol (Biomedical Research Service).

Collection of tumor tissues

Tumors were excised, dissected free of the skin and body tissue and weighed on a digital balance. Then, the tumors were immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and maintained at −80°C until ready for sectioning. For immunofluorescence analysis, frozen sections (6 µm) were cut on a Cryostats microtome (Thermo Scientific), placed on glass slides and stored at −20°C until they were used.

Tumor cell apoptosis

Tumor sections were stained by Hoechst 33342, and the level of the tumor cell apoptosis was analyzed by DeadEnd™ Fluorometric TUNEL System, according to the protocol described by the supplier. The pictures were taken by the confocal microscopy. The slides were visualized by light microscopy at 10× magnification.

Evaluation of survivin mRNA expression with RT-PCR

Survivin mRNA expression was assayed from different tumor tissues by performing the quantitative real-time PCR method, as described previously (15). Briefly, tumors were vortexed in a 1.5mL tube containing 1 mL of cold PBS. Total RNA was isolated from the cells using the RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. This isolated RNA was treated with DNase, followed by RNA quantification using a ND-1000 NanoDrop spectrophotometer. cDNA synthesis and subsequent PCR amplification were performed using 1 µg of the isolated RNA, random hexamers and Reverse Transcriptase enzyme as per the First strand cDNA synthesisTM kit from Roche. qRT-PCR assay was performed on triplicate samples the SYBR Green I Master® from Roche™ on the LightCycler® 480 qRT-PCR machine from Roche™ as described previously (15). The following survivin primer sequence: human survivin: (Forward, 5’-CTGCCTGGCAGCCCTTT-3’) and (Reverse, 5’-CCTCCAAGAAGGGCCAGTTC-3’), (16), β-actin; (Forward, 5’-ACCGAGCGCGGCTACAGT-3’), (Reverse, 5’CTTAATGTCACGCACGATTTC-3’) was used as an internal control. All custom primers were designed using the Invitrogen OligoPerfect™ Designer to have between 50–60% GC content, an annealing temperature of ~60°C and a length of 20 bases. No template controls (NTC) were run on each plate as well as done to verify that there was neither unspecific amplification nor the formation of primer dimers. Data were analyzed using the Roche quantification method Δ(ΔCt) and were normalized to β-actin and compared to control levels. The relative expression levels are expressed as a percentage of the indicated control.

Determination of survivin protein expression by immunofluorescence analysis

Survivin immunofluorescence analysis was performed on frozen tumor sections. Tumor sections were fixed with 4% of paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature. After washing twice with PBS, slides were immersed in 0.5 % of H2O2/PBS solution at room temperature for 10 min to block the endogenous peroxidase activity. The slides were rinsed in PBS solution with two changes, 5 min each, and then, incubated in 1% of Triton X-100 solution for 10 min. Enzymatic activity and non-specific binding sites were blocked by incubating the slides in 10% of FBS for 1 hour at room temperature in a humidified chamber. Subsequently, replicate sections were incubated at 4°C overnight with a primary rabbit anti-survivin antibody (AF886; R&D System) at the final concentration of 10 µg/ml. Thorough rinsing was followed by the incubation with the red-fluorescent dye-labeled anti-rabbit IgG (10 µg/ml; T6391; Life Technologies) for 1 hour. Negative controls for each tissue section were performed leaving out the primary antibody. Finally, the nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (5 µM) for 15 min at room temperature and the stained sections were observed and photographed using a Nikon Eclipse E400 microscope and a Spot Advanced software (Spot Imaging). To quantify the survivin protein levels from the images, the cell fluorescent intensity was measured with ImageJ.

Evaluation of the simultaneous intra-tumor accumulation of PXL and down-regulation of survivin expression in tumor sections

For this experiment, mice (n=3) were injected once with survivin siRNA/PXL PM. After 48 hours the animals were injected with survivin siRNA/PXL PM containing Oregon Green labeled PXL (0.1% w/w). After 1 hour the animals were sacrificed. Tumors were excised and processed as above under light protection. At the same time, the intra-tumor accumulation of Oregon Green labeled PXL and survivin protein expression were evaluated. The survivin protein expression was evaluated by the immunofluorescence analysis as described above. The nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342. Negative control, such as untreated tumor sections and sections exposed to the secondary antibody only, were processed as described above. Images were recorded by confocal microscopy.

Tubulin immunostaining

Frozen sections were processed as above and incubated with a monoclonal antibody against β-tubulin (G-8; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; dilution 1:50) for overnight at 4°C. After washing, the sections were incubated with a secondary Alexa Fluor 488-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG targeting antibody (dilution 1:100) for 1 hour at room temperature. Then, after washing, the sections were incubated with Hoechst 33342 (5 µM) for nuclear staining. The slides were mounted on glass slides with Fluoromount-G (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) medium and sealed using a nail lacquer. Negative control sections were exposed to the secondary antibody only and processed as described above. The slides were observed with a Zeiss LSM 700 inverted confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss Co. Ltd., Jena, Germany) equipped with a 63×, 1.4-numerical aperture plan-apochromat oil-immersion objective. The images were analyzed using the ImageJ version 1.42.

Statistical analysis

For comparison of several groups, one-way ANOVA for multiple groups, followed by Newmane-Keuls test if P < 0.05 was performed using the GraphPad Prism version 5.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc, San Diego, CA). All numerical data are expressed as mean ± SD, n = 3 or more, from 3 different experiments. Any p values less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The characteristics of the developed multifunctional PM are summarized in the Table 1. Survivin siRNA/PXL PM have a mean diameter of about 25 nm and a very narrow size distribution (P.I. ≤ 0.2). The chromatographic analysis of the amount of survivin siRNA-S-S-PE and PXL entrapped in the same PM, was performed as previously reported by Salzano G et al. (11). HPLC analysis of non-incorporated siRNA and PXL showed an actual loading of ~1 µg of survivin siRNA-S-S-PE /mg polymer and ~22 µg of PXL /mg polymer, corresponding to an incorporation efficiency of ~50% and ~90%, respectively.

Table 1.

Physical characteristics of PM-based formulations.

| Formulation | Mean Diameter (nm ± SD) |

P.I. ± SD | Survivin siRNA incorporation efficiency (% ± SD) |

PXL incorporation efficiency (% ± SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survivin siRNA/PXL PM | 25.0 ± 3.6 | 0.190 ± 0.07 | 51.0 ± 2.5 | 89.9 ± 3.5 |

| Survivin siRNA PM | 23.0 ± 2.1 | 0.182 ± 0.10 | 50.6 ± 1.5 | - |

| Scrambled siRNA/PXL PM | 22.9 ± 1.5 | 0.195 ± 0.05 | 52.2 ± 3.0 | 90.1 ± 2.4 |

In vivo anti-tumor activity of survivin siRNA/PXL PM in xenografted mice

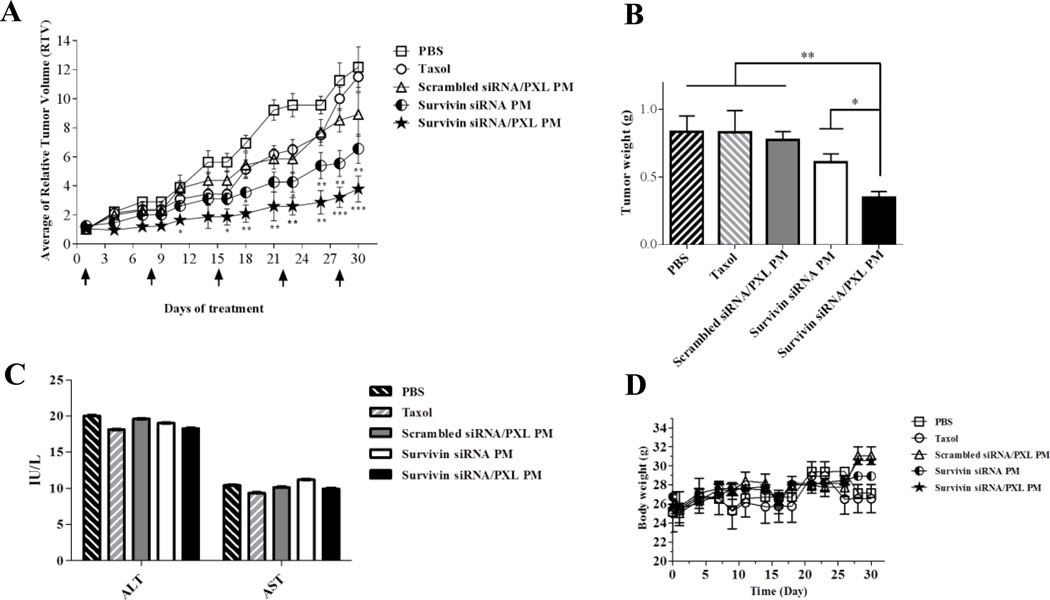

The antitumor efficiency of the co-delivery of anti-survivin siRNA and PXL in the same PM was evaluated in an animal model of SKOV3-tr xenografts. As shown in Figure 1A, PXL alone, in Cremophor solution (Taxol) or incorporated in PM (scrambled siRNA/PXL PM), did not induce a significant effect on the tumor growth. In contrast, following the treatment of the animals with PM containing survivin siRNA alone or in combination with PXL, the therapeutic outcome was significantly enhanced. The treatment with survivin siRNA alone was able to induce a significant slowing of the tumor growth. This effect was even more pronounced in survivin siRNA/PXL PM treated group. The treatment of animals with the combination of siRNA and PXL in PM elicited the highest antitumor activity, showing the least RTV among all the treatment groups (P < 0.05). Moreover, the post-mortem tumor weights of mice treated with this schedule were significantly reduced compared to all the control groups (P < 0.01) (Figure 1B). None of the agents caused any noticeable toxicity, since we did not detect significant changes in body weight (Figure 1D), toxic adverse events or deaths, confirming low non-specific toxicity of the treatments. To monitor the general toxicity after repeated doses of the treatments, the serum levels of ALT and AST were measured. As presented in Figure 1C, there was no significant decrease in ALT and AST levels in serum following all the treatment procedures, suggesting the absence of liver toxicity induced by the treatments.

Figure 1.

(A) In vivo antitumor activity of survivin siRNA/PXL PM in SKOV3-tr xenografts. Survivin siRNA/PXL PM were administered at a final concentration of anti-survivin siRNA and PXL of 1 and 10 mg/kg, respectively, once per week for 5 consecutive weeks. Relative tumor volume (RTV) values (tumor volume in mm3 on day ‘n’ (Vn) / tumor volume at the start of the treatment (Vo) plotted versus time in days) are reported. Data were given as mean ± SD for each treatment group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.005 were obtained by comparing each treatment group with Taxol group. (B) Post-mortem tumor weights. On day 30, eterotopically implanted tumors were weighed and plotted. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 were considered significant and very significant, respectively, and were obtained by comparing each treatment group with survivin siRNA/PXL group. (C) Evaluation of repeated dosing toxicity in mice by measurement of changes in serum levels of transaminase (AST/ALT). Data were given as mean ± SD for each treatment group. (D) Changes in body weight by measurement of the body weight of the mice three times a week for 5 consecutive weeks. Data were given as mean ± SD for each treatment group. N.s. means no statistical significance between the different groups.

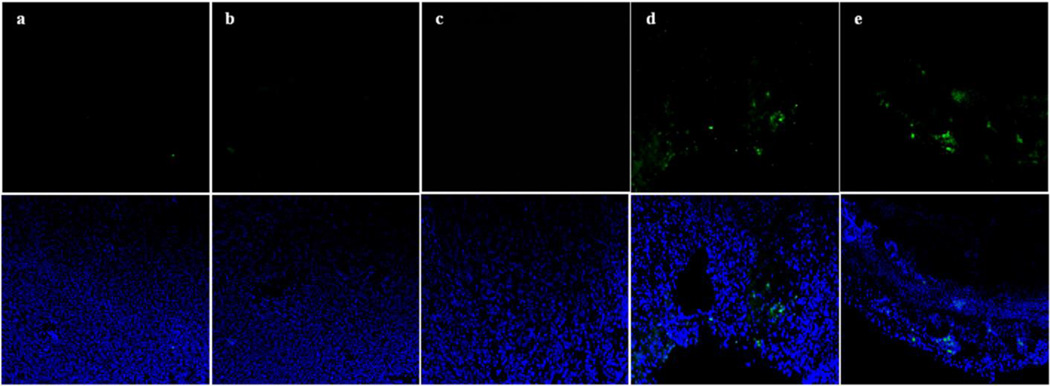

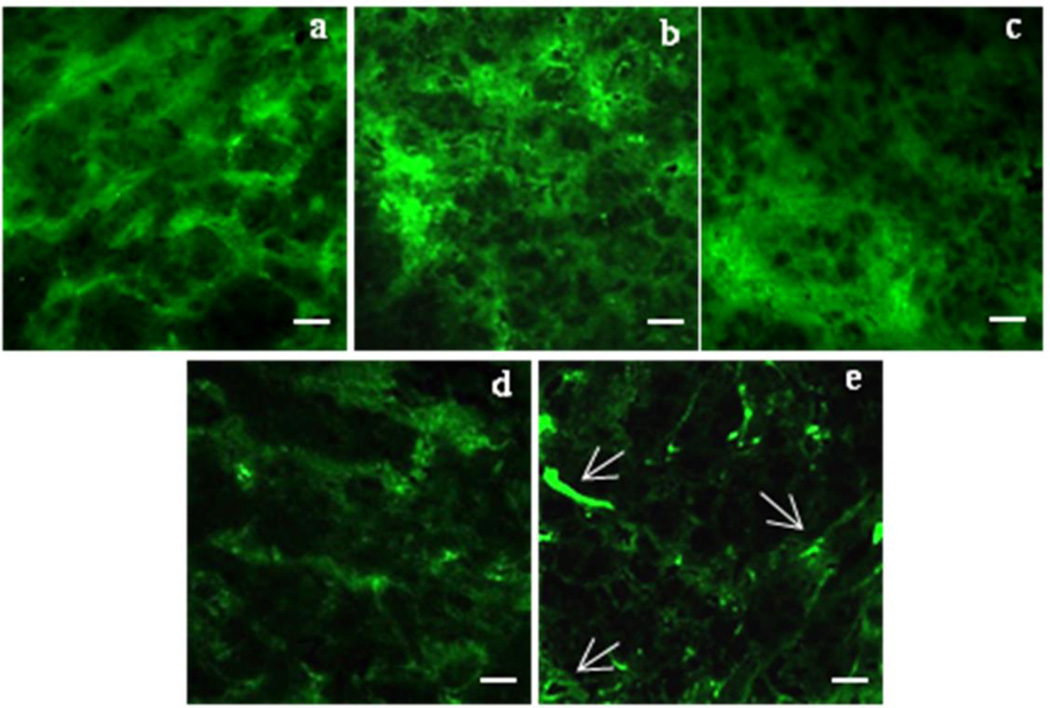

Tumor cell apoptosis

In order to investigate the cellular mechanisms of the tumor growth inhibition in mice treated with survivin siRNA/PXL PM, the level of the apoptosis in tumor tissues was evaluated. Tumor sections of tumors dissected from the previous experiment were stained by Hoechst 33342, and the level of the apoptosis was analyzed by the TUNEL assay under the confocal microscopy. As shown in Figure 2, the co-delivery of PXL and survivin siRNA leads to the highest rate of cell apoptosis (Figure 2e), which was clearly superior to all the other treatment groups (Figure 2a–d).

Figure 2. Apoptosis analysis on tumor sections by the TUNEL assay.

Pictures were taken by the confocal microscopy (10× magnification). The nuclei were stained for Hoechst 33342 (blue) and apoptotic cells (green) for Tunel. Representative images of (a) Untreated, (b) Scrambled siRNA/PXL PM,(c) Taxol, (d) Survivin siRNA PM, (e) Survivin siRNA/PXL PM groups.

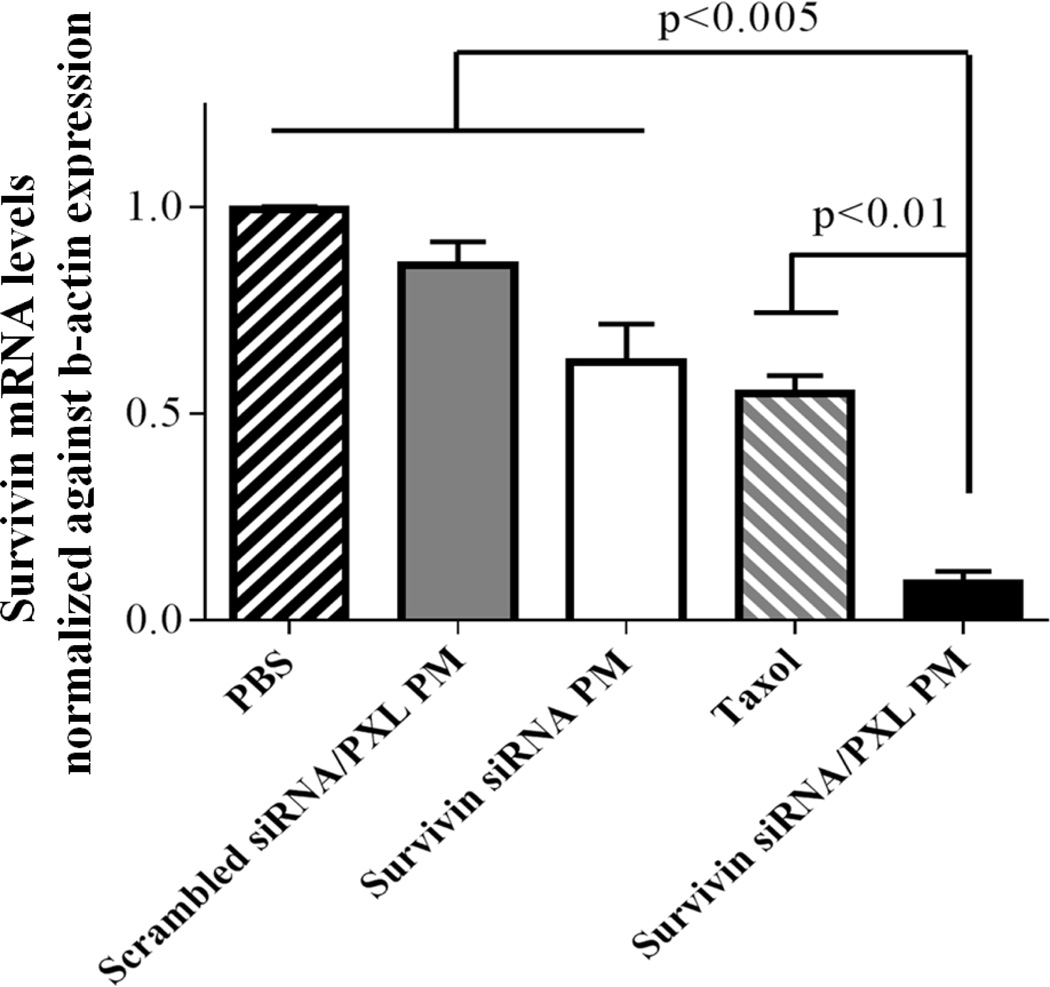

Down-regulation of survivin mRNA expression in vivo

To provide the evidence that the inhibition of the tumor growth by using survivin siRNA/PXL PM was due to the ability of this preparation (siRNA component) to down-regulate survivin in vivo, the transcriptional mRNA of the survivin gene expression was evaluated in tumor tissues by rt-PCR. Experiments were repeated three times. The relative levels of survivin mRNA in tumor tissues were normalized against mRNA of an internal control gene, β-actin, performed in the same run. As shown in Figure 3, the relative levels of survivin mRNA in mice treated with survivin siRNA/PXL PM (0.09±0.03) were significantly decreased compared to those in untreated (0.99±0.007) and scrambled siRNA/PXL PM (0.86±0.05) animal groups. The co-delivery of anti-survivin siRNA and PXL showed an inhibitory rate of survivin mRNA of about 90%. Interestingly, the treatment with Taxol could also reduce the survivin expression in tumors to a certain extent (Figure 3). In according with the results previously reported by Hu Q et al. (17), free PXL temporarily reduces the expression of survivin as a result of mitosis inhibition. These results indicated that the combination of an anti-survivin siRNA with a chemotherapeutic agent, such as PXL, with effective silencing propriety on survivin expression, could be a powerful approach to treat MDR tumors.

Figure 3. Survivin mRNA levels in tumor tissues by rt-PCR analysis.

Data were given as mean ± SD for each treatment group. ***p < 0.005, **p < 0.01 were obtained by comparing each treatment group with survivin siRNA/PXL group.

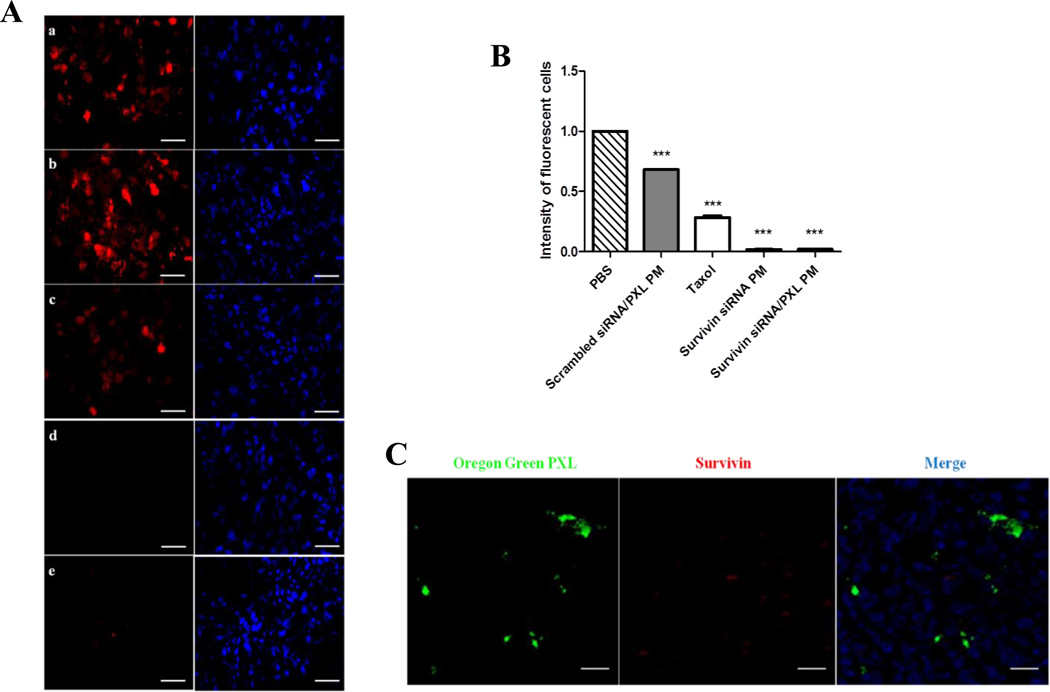

Espression of survivin protein detected by immunofluorescence analysis

In order to confirm the results obtained by qRT-PCR analysis, protein levels of survivin in tumor tissues were investigated by immunofluorescence analysis. As shown in Figure 4A and 4B, the microscopic examination of stained tumor sections showed strong immunoreactivity for survivin (red color) in untreated and scrambled siRNA/PXL PM groups. In contrast, the intensity of survivin signal was dramatically decreased in survivin siRNA PM and survivin siRNA/PXL PM treated groups (Figures 4A–B). Furthermore, the simultaneous delivery of PXL and siRNA in tumors was examinated by the confocal laser scanning microscope. For confocal microscopy observation, the immunostaining for survivin was used to evaluate the gene silencing, while the Oregon Green-labeled PXL was used to follow the drug. The mice were treated once with survivin siRNA/PXL PM. After 48 hours, the animals were injected with survivin siRNA/PXL PM containing Oregon Green-labeled PXL. One hour later, the animals were sacrificed and tumor sections were processed under light protection. The confocal microscopy study showed clearly that Oregon Green labeled PXL was transported in the tumor tissues and survivin was significantly down-regulated (Figure 4C). It is interesting to note that, a single administration of survivin siRNA/PXL PM was able to efficiently down-regulate survivin expression in tumors, as suggested by the almost complete absence of the survivin red signal in the sections.

Figure 4.

(A). Immunohystochemistry analysis. Survivin protein levels were evaluated by the fluorescent microscopy (50 ×). Representative images of three independent experiments showing survivin expression (in red) and nuclei staining with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Untreated group (a); Scrambled siRNA/PXL PM group (b); Taxol group (c); Survivin siRNA PM group (d); Survivin siRNA/PXL PM group (e). Scale bar 20 µm. (B). Cell fluorescent intensity of the survivin protein levels measured with ImageJ. ***p < 0.005 was obtained by comparing the cell fluorescence of each treatment group with PBS group (C). Simultaneous down-regulation of survivin expression and PXL penetration in tumor tissues by using survivin siRNA/PXL PM. At the same time, the intra-tumor accumulation of Oregon Green labeled PXL (left) and survivin protein expression (middle) were evaluated on tumor sections by confocal microscopy (magnification 63×). Scale bar 20 µm.

Effect of survivin siRNA/PXL PM on microtubule conformation of ovarian cancer xenografts

Previously, we have shown that survivin down-regulation enhanced the PXL activity on microtubule organization in SKOV3-tr cells (11). After down-regulation of survivin levels by treating cells with survivin siRNA PM, PXL was able to destabilize the microtubule organization at a very low concentration and exposure time. Here, to assess the effect of survivin siRNA/PXL PM on microtubule organization in vivo, SKOV3-tr tumor sections were incubated with an anti-tubulin fluorescent antibody. As shown in Figure 5a, in untreated mice, tumor cells exhibited staining of elongated microtubule fibers, demonstrative of an intact microtubule network. No significant differences were observed in all the control groups (Figure 5 b–c). At the same time, survivin siRNA/PXL PM group showed a microtubule-staining organization that was markedly different from all the other treatments (Figure 5e). In particular, as indicated by the arrows, in survivin siRNA/PXL PM-treated mice, the tumor cells exhibited diffuse organization of microtubules (Figure 5e). This result can be demonstrative of a compromised microtubule network, as previously reported in vitro (11).

Figure 5. Microtubule organization after treatment with survivin siRNA/PXL PM in vivo.

SKOV3-tr tumor sections were stained for β-tubulin (green). a-e: Representative images of three independent experiments showing the organization of microtubules (magnification 63×). Untreated group (a); scrambled siRNA/PXL PM group (b); Taxol group (c); survivin siRNA PM group (d); survivin siRNA/PXL PM group (e). Scale bar 10 µm.

Discussion

Resistance to chemotherapy is a major cause of treatment failure and relapse of many cancer types, including ovarian cancer. Survivin is one of the most tumor-specific molecules, which is selectively over-expressed in cancer tissues where it antagonizes apoptosis, stimulates tumor-associated angiogenesis, and promotes cell growth by stabilizing the microtubules organization (18). In the last years, the retrospective analysis of patient specimens and xenografts tumor data are pointing out that there is a clear connection between the existence of high levels of survivin protein and the resistance to therapy and poor prognosis in multiple tumor types (19–22). In the particular case of ovarian cancer, the prognostic role of survivin is not clear due to some conflicting results (23–26). However, the potential of survivin as a target for apoptosis-based therapy is well-established (27). The inhibition of survivin using the transcriptional repressor, YM155 sensitized primary cell cultures to cisplatin and decreased the tumor size of OVCa ovarian cancer xenografts (28). The use of siRNA to down-regulate the survivin expression has been proposed as an alternative strategy to sensitize and strengthen the tumor response. The combination of PXL and survivin RNAi down-regulation induced synergistic apoptosis in vitro and inhibited tumor growth in ovarian cancer SKOV-3 xenografts (29, 17). Despite, the exact mechanism of such a significant chemo-sensitization effect is still not clear, there are evidences that up-regulated levels of survivin preserve the microtubules network (30). The interaction of survivin with microtubules of the mitotic spindle results to a protection of cancer cells from PXL-mediated apoptosis. The disruption of survivin-microtubule interactions and the down-regulation of survivin by using siRNA can results in loss of survivin-mediated resistance to apoptosis. The translation of PXL and anti-survivin siRNA combinations in the clinical settings is challenging because of the lack of appropriate delivery systems. On the one hand, siRNA has a poor pharmacokinetic profile upon intravenous injection, i.e. fast degradation, fast clearance, and it cannot cross cellular membranes per se. This impairs tumor accumulation and the subsequent cellular internalization of siRNA. Current siRNA carriers, such as cationic lipidic or polymeric nanoparticles, fail in their in vivo stability and safety (31–33). On the other hand, PXL has a very low solubility in aqueous solution and, to be intravenously injected, requires to be formulated with ethanol and Cremophor, the commercial formulation Taxol, which is associated with serious side effects including hypersensitivity, myelosupression and neurotoxicity (34–36). Therefore, there is a clear need of alternative formulations for both siRNA and PXL that improve their stability, are suitable for intravenous injection, and lack of carrier-related toxicities.

We previously reported on bio-reductive PM for siRNA delivery based on siRNA conjugated to PE via a disulfide linkage. The inclusion of siRNA-PE conjugate into PEG2000-PE micelles further stabilized the siRNA preventing its nucleolytic degradation and allowing its release in free and biologically active form inside the cells by intracellular glutathione (10). In vitro cytotoxicity and survivin protein levels studies revealed the ability of survivin siRNA PM to down-regulate the survivin in different cancer cell lines and sensitize the cells to PXL. In addition, PXL and survivin siRNA simultaneously delivered in PM were especially active in resistant ovarian cancer cells, leading to superior cytotoxicity compared to their sequential administration (11). The present study aims to validate the utility and safety of these nanopreparations in vivo for intravenous co-delivery of siRNA and PXL to distant tumors and verify their activity in a resistant ovarian cancer model.

For the preparation of PM containing anti-survivin siRNA and PXL, we first reversibly modified anti-survivin siRNA with a PE lipid moiety via disulfide linkage by a facile chemical conjugation. Then, PXL and conjugated siRNA were incorporated into PEG2000-PE PM by one-step polymer film hydratation. The PM showed high colloidal stability, high drug incorporation efficiency (90% and 50%, for PXL and siRNA, respectively) and small particle sizes. Usually, cationic nanoparticles commonly employed for siRNA formulation need to be freshly prepared right before injection to avoid premature precipitation and loss of activity. The PM retained their technological properties for hours and even days after their preparation and do not require the use of toxic excipients for their preparation. Intravenous injection of PM was well-tolerated by the mice. We did not observe any signs of blood aggregation or hemolytic activity, pulmonary embolism or fatigue reported in the case of cationic carriers (33), or cremophor-like hypersensitivity reactions (37). In addition to their safety, the small particle size of PM (25 nm) ensured extravasation and accumulation of the PXL/siRNA cargo in the tumor by the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect (38, 39). We detected the presence of PXL in tumor sections 2 hours post-injection of PM (Figure 4B). We also verified the release of free and active siRNA inside tumoral cells by the strong survivin down-regulation 24 hours post-single-injection of anti-survivin siRNA PM (Figure 4B).

The anti-tumor effect of anti-survivin siRNA and PXL co-loaded in PM was demonstrated in nude mice bearing SKOV3-tr tumors. The animals were treated with Taxol, scrambled siRNA/PXL PM, survivin siRNA PM and survivin siRNA/PXL PM once a week for five consecutive weeks at doses of of 1 and 10mg/kg for siRNA and PXL, respectively. During the treatment, the overall health of the animals was good. No weight loss or evident hepatoxicity was found after repeated doses of the different PM formulations or even Taxol (Figure 1C–D). It is worth noticing that intravenous injections of Taxol (PXL~ 10 mg/kg) trice a week produced significant body loss in SKOV-3 xenografted mice with poor improvement in the therapeutic outcome.

Combination of PXL and survivin siRNA in PM resulted in sensitization of resistant tumors to PXL and improved anti-cancer activity. As shown in Figure 1A, the co-delivery of anti-survivin siRNA and PXL in PM inhibited tumor growth and exceeded the therapeutic effect of the single agents. Mice treated with survivin siRNA/PXL PM showed a 4-fold tumor volume reduction as compared to saline control that was consistent with the half-reduction in tumor weight after sacrifice the animals. Survivin down-regulation by survivin siRNA PM exhibited certain anti-cancer activity although lesser than the one obtained after treatment with survivin siRNA/PXL PM. This intrinsic anti-cancer activity was already described in SKOV3 animal models after direct tumor injection of survivin shRNA (40). Finally, the lack of therapeutic response of PXL either as Taxol or incorporated into scrambled siRNA/PXL PM demonstrated that survivin down-regulation mediated the sensitization of resistant tumors to non-effective doses of PXL.

Sequence-specific down-regulation by survivin siRNA in PM was confirmed in excised tumors (Figure 3). Taxol-treated tumors had significant decreased levels of survivin mRNA as previously described (41). Only those nanopreparations containing anti-survivin siRNA were able to consistently decrease survivin mRNA and protein levels at the same extent.

We further characterized the tumor response to survivin siRNA and PXL combination by the detection of apoptosis in tumor sections. The degree of apoptosis (Figure 2) correlated well with the tumor growth curves. The highest level of tumor apoptosis was found for survivin siRNA/PXL PM followed by survivin siRNA PM, whereas no significant apoptosis increase was found for PXL formulations (Figure 2). Finally, the restoration of PXL sensitivity by survivin siRNA/PXL PM treatment was also noticed by the changes in the microtubule network in tubulin-stained tumor sections (Figure 5). Similar to what we observed in vitro (11), survivin siRNA/PXL PM treatment resulted in more intensively stained tubulin as compared with the rest of the preparations, consistent with an improvement of the micro-tubule-stabilizing activity of PXL (42).

Conclusions

We have developed a micellar nanopreparation (PM) containing anti-survivin siRNA as siRNA-S-S-PE conjugate and PXL for the treatment of ovarian cancer. The developed system allows for easy and highly efficient co-encapsulation of chemotherapeutic drugs and siRNA, showed high colloidal stability and had small particle sizes compatible with parenteral administration. The micelles accumulate in distal tumors and delivered anti-survivin siRNA and PXL in sufficiently high amounts to mediate a potent and specific survivin down-regulation and improved anti-cancer activity as compared to single agents. Survivin down-regulation by anti-survivin siRNA/PXL PM mediated the sensitization of the resistant ovarian tumor to non-effective doses of PXL. Finally, the system avoids the use of toxic excipients and is well-tolerated by the animals even after repeated dosing.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant number U54 CA151881). The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Marcus CS, Maxwell GL, Darcy KM, Hamilton CA, McGuire WP. Current Approaches and Challenges in Managing and Monitoring Treatment Response in Ovarian Cancer. J Cancer. 2014;5:25–30. doi: 10.7150/jca.7810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kigawa J. New Strategy for Overcoming Resistance to Chemotherapy of Ovarian Cancer. Yonago Acta Med. 2013;56:43–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pennati M, Folini M, Zaffaroni N. Targeting survivin in cancer therapy. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2008;12:463–476. doi: 10.1517/14728222.12.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li F. Role of survivin and its splice variants in tumorigenesis. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:212–216. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ambrosini G, Adida C, Altieri DC. A novel anti-apoptosis gene, survivin, expressed in cancer and lymphoma. Nat Med. 1997;3:917–921. doi: 10.1038/nm0897-917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salz W, Eisenberg D, Plescia J, Garlick DS, Weiss RM, Wu XR, et al. A survivin gene signature predicts aggressive tumor behavior. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3531–3534. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaffaroni N, Pennati M, Colella G, Perego P, Supino R, Gatti L, et al. Expression of the antiapoptotic gene survivin correlates with taxol resistance in human ovarian cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:1406–1412. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8518-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhen HN, Li LW, Zhang W, Fei Z, Shi CH, Yang TT, et al. Short hairpin RNA targeting survivin inhibits growth and angiogenesis of glioma U251 cells. Int J Oncol. 2007;31:1111–1117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carvalho A, Carmena M, Sambade C, Earnshaw WC, Wheatley SP. Survivin is required for stable checkpoint activation in taxol-treated HeLa cells. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:2987–2998. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Musacchio T, Vaze O, D'Souza G, Torchilin VP. Effective stabilization and delivery of siRNA: reversible siRNA-phospholipid conjugate in nanosized mixed polymeric micelles. Bioconjug Chem. 2010;21:1530–1536. doi: 10.1021/bc100199c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salzano G, Riehle R, Navarro G, Perche F, De Rosa G, Torchilin VP. Polymeric micelles containing reversibly phospholipid-modified anti-survivin siRNA: a promising strategy to overcome drug resistance in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014;343:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gandhi NS, Tekade RK, Chougule MB. Nanocarrier mediated delivery of siRNA/miRNA in combination with chemotherapeutic agents for cancer therapy: Current progress and advances. J Control Release. 2014;194C:238–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duan Z, Lamendola DE, Duan Y, Yusuf RZ, Seiden MV. Description of paclitaxel resistance-associated genes in ovarian and breast cancer cell lines. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2005;55:277–285. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0878-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomayko MM, Reynolds CP. Determination of subcutaneous tumor size in athymic (nude) mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1989;24:148–154. doi: 10.1007/BF00300234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trivedi MS, Shah JJ, Hodgson NW, Hyang-Min B, Deth RC. Morphine Induces Redox-based Changes in Global DNA Methylation and Retrotransposon Transcription by Inhibition Of EAAT3-Mediated Cysteine Uptake. Mol Pharmacol. 2014;85:747–757. doi: 10.1124/mol.114.091728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakahara T, Kita A, Yamanaka K, Mori M, Amino N, Takeuchi M, et al. YM155, a novel small-molecule survivin suppressant, induces regression of established human hormone-refractory prostate tumor xenografts. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8014–8021. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1343. Erratum in Cancer Res 2012;72:3886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu Q, Li W, Hu X, Hu Q, Shen J, Jin X, et al. Synergistic treatment of ovarian cancer by codelivery of survivin shRNA and paclitaxel via supramolecular micellar assembly. Biomaterials. 2012;33:6580–6591. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altieri DC. Survivin, cancer networks and pathway-directed drug discovery. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nrc2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart DJ. Tumor and host factors that may limit efficacy of chemotherapy in non-small cell and small cell lung cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2010;75:173–234. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith SD, Wheeler MA, Plescia J, Colberg JW, Weiss RM, Altieri DC. Urine detection of survivin and diagnosis of bladder cancer. JAMA. 2001;285:324–328. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song J, Su H, Zhou YY, Guo LL. Prognostic value of survivin expression in breast cancer patients: a meta-analysis. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:2053–2062. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0848-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paik S, Shak S, Tang G, Kim C, Baker J, Cronin M, et al. A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2817–2826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zaffaroni N, Daidone MG. Survivin expression and resistance to anticancer treatments: perspectives for new therapeutic interventions. Drug Resist Updat. 2002;5:65–72. doi: 10.1016/s1368-7646(02)00049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen L, Liang L, Yan X, Liu N, Gong L, Pan S, et al. Survivin status affects prognosis and chemosensitivity in epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2013;23:256–263. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0b013e31827ad2b8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferrandina G, Legge F, Martinelli E, Ranelletti FO, Zannoni GF, Lauriola L, et al. Survivin expression in ovarian cancer and its correlation with clinico-pathological, surgical and apoptosis-related parameters. Br J Cancer. 2005;92:271–277. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Felisiak-Golabek A, Rembiszewska A, Rzepecka IK, Szafron L, Madry R, Murawska M, et al. Nuclear survivin expression is a positive prognostic factor in taxane-platinum-treated ovarian cancer patients. J Ovarian Res. 2011;4:20. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-4-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Church DN, Talbot DC. Survivin in solid tumors: rationale for development of inhibitors. Curr Oncol Rep. 2012;14:120–128. doi: 10.1007/s11912-012-0215-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mir R, Stanzani E, Martinez-Soler F, Villanueva A, Vidal A, Condom E, et al. YM155 sensitizes ovarian cancer cells to cisplatin inducing apoptosis and tumor regression. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132:211–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xing J, Jia CR, Wang Y, Guo J, Cai Y. Effect of shRNA targeting survivin on ovarian cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:1221–1229. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1196-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tran J, Master Z, Yu JL, Rak J, Dumont DJ, Kerbel RS. A role for survivin in chemoresistance of endothelial cells mediated by VEGF. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4349–4354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072586399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang J, Lu Z, Yeung BZ, Wientjes MG, Cole DJ, Au JL. Tumor priming enhances siRNA delivery and transfection in intraperitoneal tumors. J Control Release. 2014;178C:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Musacchio T, Torchilin VP. siRNA delivery: from basics to therapeutic applications. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2013;18:58–79. doi: 10.2741/4087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ballarín-González B, Howard KA. Polycation-based nanoparticle delivery of RNAi therapeutics: adverse effects and solutions. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012;64:1717–1729. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singla AK, Garg A, Aggarwal D. Paclitaxel and its formulations. Int J Pharm. 2002;235:179–192. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5173(01)00986-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anon. Paclitaxel (taxol) for ovarian cancer. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 1993;35:39–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weiss RB, Donehower RC, Wiernik PH, Ohnuma T, Gralla RJ, Trump DL, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions from taxol. J Clin Oncol. 1990;8:1263–1268. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1990.8.7.1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim SC, Kim DW, Shim YH, Bang JS, Oh HS, Wan Kim S, et al. In vivo evaluation of polymeric micellar paclitaxel formulation: toxicity and efficacy. J Control Release. 2001;72:191–202. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00275-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monsky WL, Fukumura D, Gohongi T, Ancukiewcz M, Weich HA, Torchilin VP, et al. Augmentation of transvascular transport of macromolecules and nanoparticles in tumors using vascular endothelial growth factor. Cancer Res. 1999;59:4129–4135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davis ME, Chen ZG, Shin DM. Nanoparticle therapeutics: an emerging treatment modality for cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:771–782. doi: 10.1038/nrd2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xing J, Jia CR, Wang Y, Guo J, Cai Y. Effect of shRNA targeting survivin on ovarian cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138:1221–1229. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1196-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Z, Xie Y, Wang H. Changes in survivin messenger RNA level during chemotherapy treatment in ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:716–719. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.7.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anbalagan M, Ali A, Jones RK, Marsden CG, Sheng M, Carrier L, et al. Peptidomimetic Src/pretubulin inhibitor KX-01 alone and in combination with paclitaxel suppresses growth, metastasis in human ER/PR/HER2-negative tumor xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11:1936–1947. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]