Marine sponges are ubiquitous colonizers of shallow, clear-water environments in the oceans (1, 2). Sponges have emerged as significant mediators of biogeochemical fluxes in coastal zones by virtue of respiring organic matter and facilitating both the consumption and release of nutrients (3, 4). Sponges gain their nutrition through filtering out plankton and organic detritus and through uptake of dissolved organic matter from seawater (4). Many species host diverse microbial symbiont communities that contribute to digestion and nutrient release from the filtered organics, and in some species cyanobacterial symbionts can supply fresh photosynthate to meet a substantial fraction of the sponge energy requirements (5). In PNAS, Zhang et al. (6) reveal a major and heretofore unknown role for sponges with regard to the marine phosphorus cycle. The authors present strong evidence for polyphosphate (poly-P) production and storage by sponge endosymbionts. Zhang et al. also may have detected apatite, a calcium phosphate mineral, in sponge tissue. This work has major implications for our understanding of nutrient cycling in reef environments, the roles played by microbial endosymbiont communities in general, and aspects of P cycling on geologic timescales.

Reef ecosystems harbor some of the greatest concentrations of biodiversity in the marine environment (7). This diversity is supported in part by gross rates of photosynthesis that can approach those of tropical rainforests (8, 9). However, reefs persist in extremely low nutrient environments and show little net production of organic matter. Sponges have proven to be key players in facilitating this rapid treadmill of photosynthetic and respiratory turnover of carbon (4).

Sponges are major biogeochemical agents by virtue of their abundance coupled with the large volumes of water they process (Fig. 1), many species in excess of 10,000 body volumes of seawater per day (11, 12). Sponges metabolize a significant fraction of reef primary production (4) and also return organic carbon to the reef environment through shedding of cellular materials, which are rapidly consumed by detritivores (13).

Fig. 1.

Dye tracer release in a giant barrel sponge (Xestospongia muta) illustrates the rapid rate at which sponges process sea water (10). Uptake, transformation, and release of carbon and nutrients by the sponge and its endosymbiont microbial community can have a profound impact on the surrounding water quality and ecosystem. Image courtesy of Steven E. McMurray (photographer).

Sponges mediate a complex array of nutrient transformations. The net effect is to release labile nutrient forms (nitrate, nitrite, ammonium, phosphate) from less bioavailable organic molecules (3, 4, 14). Sponge endosymbionts also supply and remove fixed N to the reef ecosystem via N fixation (15) and denitrification and anaerobic ammonia oxidation (annamox) (4).

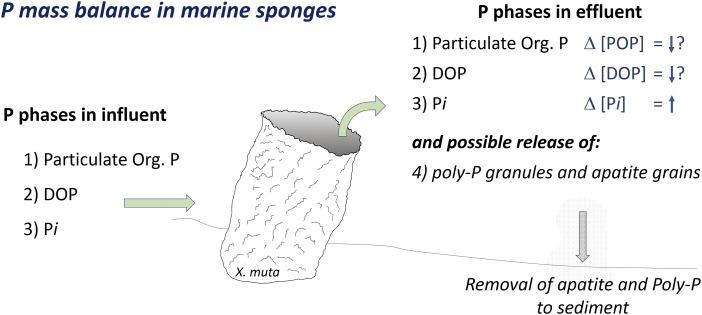

Very few studies have determined the change in concentration of dissolved and particulate P between ambient waters and sponge effluent (Fig. 2). These studies show a net release of dissolved inorganic P in the form of orthophosphate (Pi) (4). However, the change in concentrations of particulate and dissolved organic P (Δ[POP] and Δ[DOP], respectively) are rarely measured in water passing through sponges. The change in C:N:P stoichiometry between sponge inputs and outputs will influence nutrient limitation in reef environments. However, endosymbiont photosynthesis, N fixation, denitrification, and annamox all complicate this determination. Now poly-P accumulation poses another challenge to the study of the ecological stoichiometry of sponges.

Fig. 2.

Significant uncertainties persist in our understanding of P cycling by marine sponges. The direction and magnitude of P concentration changes (Δ [P phase]) upon passage through a sponge are poorly constrained (↑ or ↓ signifies an increase or decrease in concentration; “?” signifies an absence of observations). Zhang et al. (6) show that poly-P can be produced in marine sponges and may constitute up to 40% of the P found in sponge biomass. Their results raise the question of whether poly-P storage is transient and reversible, or whether substantial amounts of poly-P and apatite are shed from sponges and lost to sediments.

Zhang et al. (6) present several lines of evidence that sponge endosymbionts accumulate P in the form of poly-P granules. These lines of evidence include fluorescence microscopy, whole-tissue poly-P extraction, scanning electron microscope-energy dispersive spectroscopy compositional analysis of granules, and detection of genes and gene transcripts for poly-P kinase, an enzyme responsible for bacterial poly-P synthesis. In the three sponge species examined, poly-P constitutes 25–40% of the total P in sponge tissue.

The accumulation of abundant poly-P granules begs the question, “To what end?” The phosphoanhydride bonds that form the backbone of poly-P are analogous to those in ATP and might be used for energy storage, among other biochemical and regulatory functions (16). Alternatively, these deposits could be used to tide bacteria over during times of P famine (17). If poly-P serves mainly to protect against future P deficits, then could these bacterial poly-P granules serve as a commensal P storage medium, serving host as well as endosymbiont?

This answer would broaden our general understanding of microbial endosymbiont–host relations. The conversion of nutrients to more bioavailable forms is a fundamental function of animal gut bacterial communities. Similarly, mycorrhizal fungi extract nutrients from the soil environment, translocate the nutrients to plant roots, and release them (18). However, there has been almost no discussion of microbial endosymbionts storing nutrients for the host organism. Poly-P is used for transport of P in fungal hyphae from the soil environment to plants; there has been some speculation that this poly-P pool serves to buffer the release of Pi against fluctuations in fungal uptake of P (18). The sponge endosymbiont poly-P could prove to be among the first discoveries of direct nutrient storage by bacteria for host.

If poly-P is simply a transient reservoir used to bank energy or P, then subsequent release as Pi would lead to a temporal offset between P uptake and release by sponges. The main overall impact on P cycling in reef environments would still relate to the conversion of less labile organophosphorus forms to easily used Pi (Fig. 2).

However, if a substantial amount of sponge poly-P is released in particulate form and deposits in sediments, then this could facilitate a major sink for P in such ecosystems. Zhang et al. (6) note that poly-P could serve as a precursor phase, which converts directly to the mineral apatite or which decomposes to promote apatite supersaturation and precipitation within the sponge tissue or within sediments. Diatom-associated poly-P has been shown to contribute substantially to apatite formation in marine sediments (19). Some large sulfur bacteria can store P as poly-P. Subsequent release is linked to the formation of apatite in organic-rich sediments of marine upwelling zones (20), likely leading to the formation of geologically significant phosphorite deposits in the past.

If sponge-associated sequestration of particulate P in sediments is significant, then reef sediments should possess detectable levels of authigenic apatite. In one of the only studies to assess particulate P phases in reef sediments, biogenic and authigenic apatite were detected along a transect across the Great Barrier Reef (21). Should sponges be found to enrich sediments in poly-P and apatite, then it is plausible that they contributed to phosphatic fossilization of soft-bodied metazoans in calcareous sedimentary rocks (22), recording early stages of animal evolution.

The results from Zhang et al. (6) potentially cast sponges in a dual role with regard to reef P cycling. The release of Pi through the metabolism of particulate and dissolved organic compounds restores P to a more bioavailable form and supports reef primary production. However, the poly-P mechanism may lead to the sequestration of P in recalcitrant sediment phases (Fig. 2). A detailed investigation of the P budget for marine sponges is needed, characterizing particulate and dissolved P sources “ingested” by sponges, P storage, and P release mechanisms. The oxygen isotope composition of Pi may prove useful in tracking P regeneration mechanisms (23). The delineation of sponge P budgets, as well as the factors that determine the stoichiometry of sponge-mediated fluxes of carbon and nutrients, are important steps toward understanding the high rates of primary production and respiration in reef ecosystems. This is especially important in the context of shifts from coral-dominated to sponge-dominated reefs (24).

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 4381.

References

- 1.Diaz MC, Rützler K. Sponges: An essential component of Caribbean coral reefs. Bull Mar Sci. 2001;69(2):535–546. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bell JJ. The functional roles of marine sponges. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci. 2008;79(3):341–353. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Southwell MW, Weisz JB, Martens CS, Lindquist N. In situ fluxes of dissolved inorganic nitrogen from the sponge community on Conch Reef, Key Largo, Florida. Limnol Oceanogr. 2008;53(3):986–996. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maldonado M, Ribes M, van Duyl FC. Nutrient fluxes through sponges: Biology, budgets, and ecological implications. Adv Mar Biol. 2012;62:113–182. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394283-8.00003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Webster NS, Taylor MW. Marine sponges and their microbial symbionts: Love and other relationships. Environ Microbiol. 2012;14(2):335–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang F, et al. Phosphorus sequestration in the form of polyphosphate by microbial symbionts in marine sponges. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:4381–4386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1423768112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts CM, et al. Marine biodiversity hotspots and conservation priorities for tropical reefs. Science. 2002;295(5558):1280–1284. doi: 10.1126/science.1067728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kinsey DW. Standards of performance in coral reef primary production and carbon turnover. In: Barnes DJ, editor. Perspectives on Coral Reefs. Australian Institute of Marine Science; Townsville, Australia: 1983. pp. 209–220. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Restrepo-Coupe N, et al. What drives the seasonality of photosynthesis across the Amazon basin? A cross-site analysis of eddy flux tower measurements from the Brasil flux network. Agric Meteorol. 2013;182–183:128–144. [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMurray S, Pawlik J, Finelli C. Trait-mediated ecosystem impacts: How morphology and size affect pumping rates of the Caribbean giant barrel sponge. Aquat Biol. 2014;23(1):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reiswig HM. Water transport, respiration and energetics of three tropical marine sponges. J Exp Mar Biol Ecol. 1974;14(3):231–249. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weisz JB, Lindquist N, Martens CS. Do associated microbial abundances impact marine demosponge pumping rates and tissue densities? Oecologia. 2008;155(2):367–376. doi: 10.1007/s00442-007-0910-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Goeij JM, et al. Surviving in a marine desert: The sponge loop retains resources within coral reefs. Science. 2013;342(6154):108–110. doi: 10.1126/science.1241981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Southwell MW, Popp BN, Martens CS. Nitrification controls on fluxes and isotopic composition of nitrate from Florida Keys sponges. Mar Chem. 2008;108(1-2):96–108. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohamed NM, Colman AS, Tal Y, Hill RT. Diversity and expression of nitrogen fixation genes in bacterial symbionts of marine sponges. Environ Microbiol. 2008;10(11):2910–2921. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rao NN, Gómez-García MR, Kornberg A. Inorganic polyphosphate: Essential for growth and survival. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78(1):605–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.083007.093039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karl DM, Björkman KM. Dynamics of DOP. In: Hansell DA, Carlson C, editors. Biogeochemistry of Marine Dissolved Organic Matter. Academic; San Diego, CA: 2002. pp. 249–366. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jansa J, Finlay R, Wallander H, Smith FA, Smith SE. Role of mycorrhizal symbioses in phosphorus cycling. In: Bünemann E, Oberson A, Frossard E, editors. Phosphorus in Action. Springer; Berlin: 2011. pp. 137–168. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diaz J, et al. Marine polyphosphate: A key player in geologic phosphorus sequestration. Science. 2008;320(5876):652–655. doi: 10.1126/science.1151751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldhammer T, Brüchert V, Ferdelman TG, Zabel M. Microbial sequestration of phosphorus in anoxic upwelling sediments. Nat Geosci. 2010;3(8):557–561. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monbet P, Brunskill GJ, Zagorskis I, Pfitzner J. Phosphorus speciation in the sediment and mass balance for the central region of the Great Barrier Reef continental shelf (Australia) Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2007;71(11):2762–2779. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Creveling JR, et al. Phosphorus sources for phosphatic Cambrian carbonates. Geol Soc Am Bull. 2014;126(1-2):145–163. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colman AS, Blake RE, Karl DM, Fogel ML, Turekian KK. Marine phosphate oxygen isotopes and organic matter remineralization in the oceans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(37):13023–13028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506455102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bell JJ, Davy SK, Jones T, Taylor MW, Webster NS. Could some coral reefs become sponge reefs as our climate changes? Glob Change Biol. 2013;19(9):2613–2624. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]