Significance

The postgenomic era has seen the identification of numerous long noncoding RNA (lncRNAs) in mammalian cells; however, their biological functions remain largely unknown. Nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1 (NEAT1) is an lncRNA that participates in the construction of the massive ribonucleoprotein subnuclear complex, the paraspeckle. Paraspeckle formation proceeds in conjunction with NEAT1 biogenesis and the assembly of >40 proteins. Here, we demonstrate that SWItch/Sucrose NonFermentable (SWI/SNF) chromatin-remodeling complexes play an essential role in organizing the protein–protein interaction network of paraspeckles in a manner that does not require their canonical remodeling activity. We also show that SWI/SNF complexes are required for the assembly of the Satellite III lncRNA-dependent nuclear stress body. These data suggest the presence of a common pathway for the assembly of lncRNA-dependent nuclear bodies in mammalian cells.

Keywords: chromatin-remodeling complex, long noncoding RNA, nuclear bodies, ribonucleoprotein assembly

Abstract

Paraspeckles are subnuclear structures that form around nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1 (NEAT1) long noncoding RNA (lncRNA). Recently, paraspeckles were shown to be functional nuclear bodies involved in stress responses and the development of specific organs. Paraspeckle formation is initiated by transcription of the NEAT1 chromosomal locus and proceeds in conjunction with NEAT1 lncRNA biogenesis and a subsequent assembly step involving >40 paraspeckle proteins (PSPs). In this study, subunits of SWItch/Sucrose NonFermentable (SWI/SNF) chromatin-remodeling complexes were identified as paraspeckle components that interact with PSPs and NEAT1 lncRNA. EM observations revealed that SWI/SNF complexes were enriched in paraspeckle subdomains depleted of chromatin. Knockdown of SWI/SNF components resulted in paraspeckle disintegration, but mutation of the ATPase domain of the catalytic subunit BRG1 did not affect paraspeckle integrity, indicating that the essential role of SWI/SNF complexes in paraspeckle formation does not require their canonical activity. Knockdown of SWI/SNF complexes barely affected the levels of known essential paraspeckle components, but markedly diminished the interactions between essential PSPs, suggesting that SWI/SNF complexes facilitate organization of the PSP interaction network required for intact paraspeckle assembly. The interactions between SWI/SNF components and essential PSPs were maintained in NEAT1-depleted cells, suggesting that SWI/SNF complexes not only facilitate interactions between PSPs, but also recruit PSPs during paraspeckle assembly. SWI/SNF complexes were also required for Satellite III lncRNA-dependent formation of nuclear stress bodies under heat-shock conditions. Our data suggest the existence of a common mechanism underlying the formation of lncRNA-dependent nuclear body architectures in mammalian cells.

Paraspeckles are nuclear bodies that are typically detected as foci in close proximity to nuclear speckles (1, 2) and were initially defined as foci enriched in characteristic RNA-binding proteins, including paraspeckle component 1 (PSPC1), non-POU domain containing octamer binding (NONO), and splicing factor proline/glutamine-rich (SFPQ) (3, 4). Nuclear paraspeckle assembly transcript 1 (NEAT1), a long noncoding RNA (lncRNA), localizes exclusively to paraspeckles and acts as a core structural component of these ribonucleoprotein (RNP) bodies (5–7). Paraspeckles are ∼360 nm in diameter (8); hence, they are considered huge among RNP particles. Paraspeckles regulate the expression of a number of genes via the sequestration of specific proteins and RNAs (4, 9, 10), and are physiologically involved in the development of the corpus luteum and the mammary gland in mice (11, 12).

Paraspeckle formation is initiated by NEAT1 transcription at the NEAT1 locus on human chromosome 11 (5, 13). The NEAT1 gene generates two isoform transcripts, namely, 3.7-kb NEAT1_1 and 23-kb NEAT1_2. Both isoforms are transcribed from the same promoter and can be processed at the 3′ end to produce a canonically polyadenylated NEAT1_1 isoform and a noncanonically processed NEAT1_2 isoform (6, 7, 14). Whereas NEAT1_2 is required for de novo paraspeckle construction, NEAT1_1 is not required for this process (6, 14, 15). Extensive RNAi analyses of 40 paraspeckle proteins (PSPs) revealed that seven PSPs, namely heterogeneous nuclear RNP K (HNRNPK), NONO, RNA-binding motif protein 14 (RBM14), SFPQ, DAZ-associated protein 1 (DAZAP1), fused in sarcoma (FUS), and HNRNPH3, are essential for paraspeckle formation (14). HNRNPK, NONO, RBM14, and SFPQ (category 1A proteins), but not DAZAP1, FUS, or HNRNPH3 (category 1B proteins), are required for the accumulation of the essential NEAT1_2 isoform (14). Whereas HNRNPK facilitates NEAT1_2 synthesis by interfering with the 3′-end processing of NEAT1_1 (14), other proteins in category 1A stabilize the NEAT1_2 isoform. Although category 1B proteins barely affect NEAT1_2 accumulation, they are required for the assembly of intact paraspeckles (14). These data suggest that paraspeckle formation proceeds in conjunction with the biogenesis of NEAT1 lncRNA and subsequent RNP assembly.

SWItch/Sucrose NonFermentable (SWI/SNF) chromatin-remodeling complexes are known to disrupt nucleosome architecture and elicit changes in gene expression. They play roles in a number of biological processes and are implicated in several diseases (16). The presence of the BRG1 or the BRM subunit of SWI/SNF, which are both ATPases, is sufficient for nucleosome remodeling in vitro; however, maximal activity requires additional subunits (17). Here, we report the identification of SWI/SNF complexes as novel factors required for paraspeckle formation and demonstrate that this function does not require their ATPase activity. We demonstrate that several SWI/SNF subunits interact with known PSPs. The predominant localization of SWI/SNF components within paraspeckles was also confirmed. The results suggest a novel function of SWI/SNF complexes in the architectural lncRNA-dependent assembly of nuclear bodies.

Results

Subunits of SWI/SNF Complexes Are Major Paraspeckle Components.

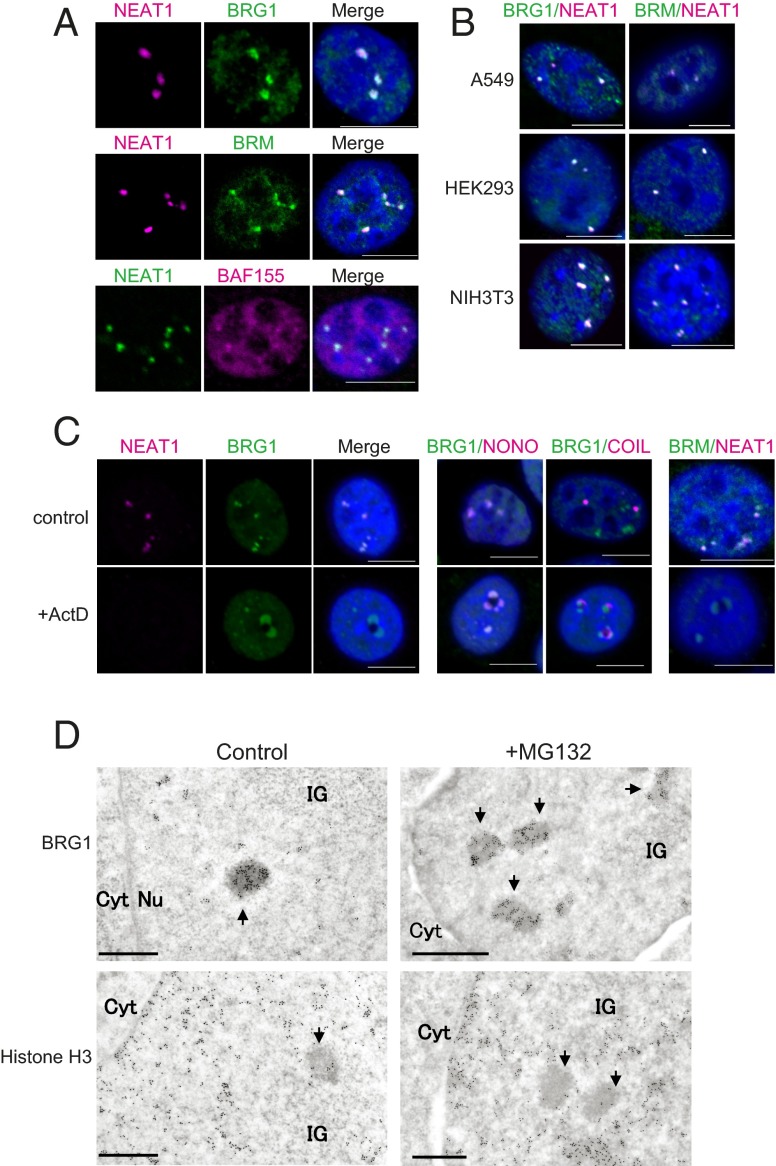

A search for proteins that interact with the 40 known PSPs in information publically available in the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins database (version 9.05; string905.embl.de) revealed core subunits of the SWI/SNF chromatin-remodeling complex, particularly essential category 1 proteins (Table 1). Immunocytochemical analyses of human HeLa cells showed that three SWI/SNF subunits (BRG1, BRM, and BAF155) exhibited broad nucleoplasmic distributions with several prominent foci that overlapped with the locations of NEAT1 lncRNA detected by RNA FISH (Fig. 1A). The specific detection of BRG1 was confirmed by using a distinct BRG1 antibody with different fixation conditions (Fig. S1A) and by observing signal disappearance upon BRG1 knockdown (Fig. S1B). Paraspeckle localization of BRG1 and BRM was also observed in other human cell lines (A549 and HEK293) and in a mouse cell line (NIH 3T3; Fig. 1B). These results indicate that a subpopulation of the SWI/SNF subunits is localized to paraspeckles.

Table 1.

PSPs that interacted with SW/SNF subunits

| SWI/SNF | PSP |

| BRG1 | NONO*, SFPQ*, CPSF7, CPSF6, SS18L1 |

| BRM | NONO*, SFPQ*, RBM14*, HNRNPK*, FUS*, HNRNPA1, HNRNPR, TARDBP1, CPSF6, RBMX, HNRNPF, HNRNPH1, SS18L1 |

| BAF170 | NONO*, SFPQ*, RBM14*, HNRNPK*, FUS*, CPSF7, HNRNPA1, HNRNPR, TARDBP1, CPSF6, NUDT21, EWSR1,RBM7, RBMX, TAF15, HNRNPF, HNRNPH1 |

| BAF155 | NONO*, SFPQ*, RBM14*, HNRNPK*, FUS*, CPSF7, HNRNPA1, HNRNPR, TARDBP1, CPSF6, NUDT21, EWSR1,RBM7, RBMX, TAF15, HNRNPF, HNRNPH1 |

| BAF57 | NONO*, SFPQ*, RBM14*, HNRNPK*, FUS*, HNRNPA1, HNRNPR, TARDBP1, NUDT21, EWSR1,RBM7, RBMX, TAF15, HNRNPF, HNRNPH1 |

| BAF47 | NONO*, SFPQ*, RBM14*, HNRNPK*, FUS*, HNRNPA1, HNRNPR, TARDBP1, NUDT21, EWSR1,RBM7, RBMX, TAF15, HNRNPF, HNRNPH1 |

The essential PSPs per Naganuma et al. (14).

Fig. 1.

Paraspeckle localization of SWI/SNF complex components. (A and B) Localization of BRG1, BRM, and BAF155 to paraspeckles in human and mouse cells. The SWI/SNF components were detected by immunocytochemical analyses, and the paraspeckles were visualized by RNA FISH analyses of NEAT1 lncRNA. The experiments were performed in HeLa cells (A) and other human cell lines (A549 and HEK293), as well as a mouse cell line (NIH 3T3) (B). (Scale bars: 10 μm.) (C) Relocalization of BRG1 and BRM to perinucleolar caps upon transcriptional arrest caused by treatment of HeLa cells with actinomycin D (+Act D). The indicated PSPs and SWI/SNF components were detected by immunocytochemical analyses, and the paraspeckles were visualized by RNA FISH analyses of NEAT1 lncRNA. NONO, which is known to relocalize to perinucleolar caps, was used as a positive control. COIL relocates to another cap structure. (Scale bars: 10 μm.) (D) I-EM detection of BRG1 (Upper) in normal (control) paraspeckles and enlarged paraspeckles induced by the treatment of HeLa cells with MG132. Chromosome localization was detected by using an anti-histone H3 antibody (Lower). The arrows indicate paraspeckles. Cyt, cytoplasm; IG, interchromatin granule clusters; Nu, nucleus. (Scale bars: 0.5 µm.)

Transcriptional inhibition by actinomycin D leads to paraspeckle disintegration and relocation of PSPs, but not NEAT1, to perinucleolar cap structures (2, 6, 14). Similarly, in our hands, treatment of HeLa cells with actinomycin D resulted in the disappearance of SWI/SNF foci and relocation of BRG1 and BRM to perinucleolar cap structures (Fig. 1C). BRG1 signals overlapped with those of other PSPs such as NONO, but not with COIL, which is known to relocate to distinct perinucleolar caps (Fig. 1C) (2, 6, 14). Furthermore, knockdown of NEAT1 with antisense oligonucleotides (Fig. S2A) resulted in the disappearance of SWI/SNF foci without affecting the levels of BRG1 and BRM (Fig. S2 B and C), indicating that SWI/SNF foci require NEAT1 for their integrity.

Immunogold EM (I-EM) detection revealed a patchy pattern of distribution of SWI/SNF, indicating that it was concentrated within paraspeckle subdomains (Fig. 1D, Upper Left). This patchy pattern of localization, which was not observed for the other PSPs (Fig. S1C), was even more evident in enlarged paraspeckles generated by treatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (9) (Fig. 1D, Upper Right). The use of an antibody against histone H3 revealed that the paraspeckle interior region, where the majority of the BRG1 protein was localized, contained very little chromatin (Fig. 1D, Lower). Taken together, these results suggest that SWI/SNF subunits are bona fide paraspeckle components that do not overlap with distinct subnuclear structures or chromosome loci.

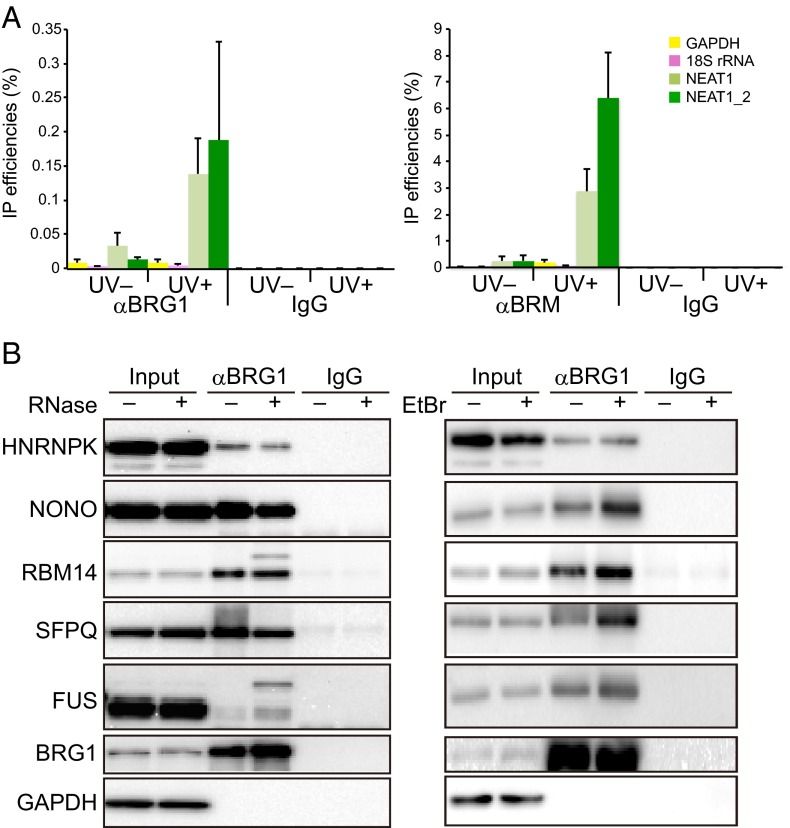

In UV cross-linking immunoprecipitation (IP) experiments, NEAT1 coimmunoprecipitated with BRG1 and BRM, but only after UV irradiation (Fig. 2A), indicating a direct interaction between NEAT1 and these SWI/SNF subunits. In addition, PSPs essential for paraspeckle formation were efficiently coimmunoprecipitated with BRG1 even after treatment with RNase A or ethidium bromide (18) (Fig. 2B), indicating the absence of an RNA or DNA bridge between the SWI/SNF subunits and PSPs. These observations suggest that SWI/SNF subunits are stable paraspeckle components.

Fig. 2.

SWI/SNF subunits interact directly with essential paraspeckle components. (A) Detection of direct interactions between SWI/SNF components (BRG1 and BRM) and NEAT1 lncRNA by UV cross-linking IP. After UV cross-linking, the coimmunoprecipitated RNAs were quantified by quantitative RT-PCR, and the IP efficiencies (as percentages) were determined (n = 3). The “UV−” lanes are negative controls without UV cross-linking. IgG was used as a negative control for IP. (B) Interactions between BRG1 and five essential PSPs (Left) detected by co-IP with an anti-BRG1 antibody (αBRG1) in the presence (+) or absence (−) of RNase A (Left) or ethidium bromide (EtBr; Right). GAPDH was detected as a negative control.

SWI/SNF Complexes Are Required for Paraspeckle Formation.

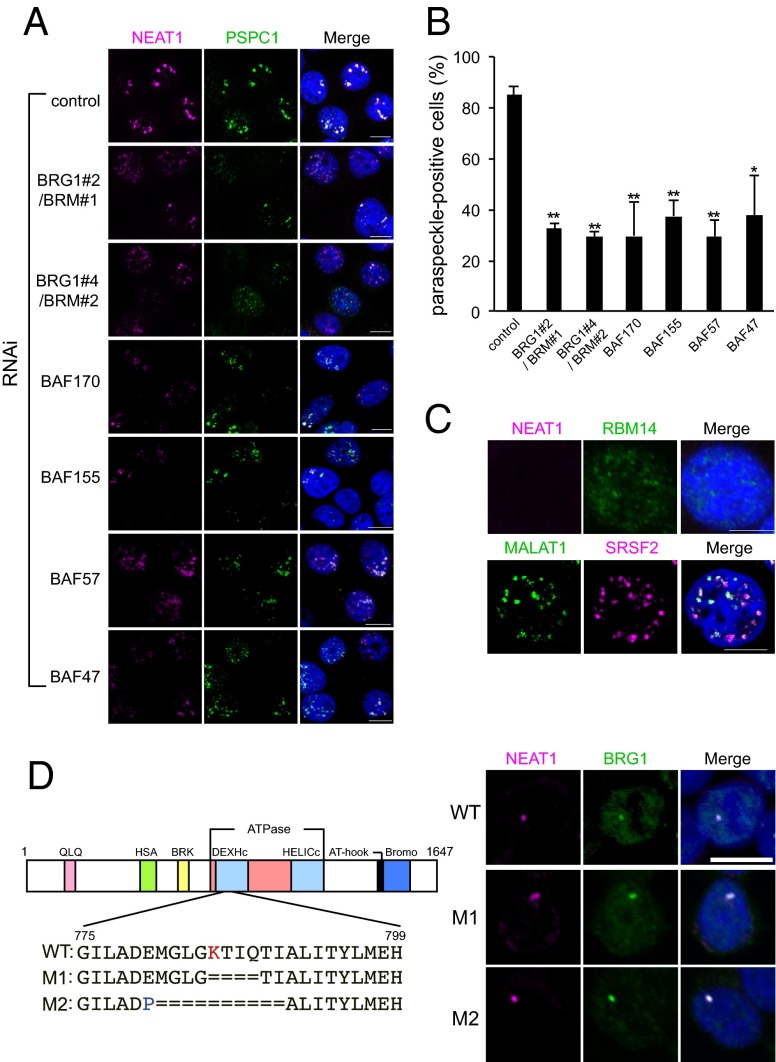

The results described here earlier raised the possibility that SWI/SNF complexes are involved in paraspeckle formation. To test this hypothesis, the expression of six SWI/SNF core subunits was impaired by RNAi and the integrity of the paraspeckle structure was examined. Single knockdown of BRG1 or BRM had no effect on paraspeckle appearance in HeLa cells (Figs. S1B and S3); however, double knockdown of BRG1 and BRM by using a combination of two siRNAs (Fig. S4A) resulted in obvious paraspeckle disintegration (Fig. 3 A and B), suggesting that these SWI/SNF subunits are functionally redundant for paraspeckle formation. Single knockdowns of four BAF proteins (BAF170, BAF155, BAF57, and BAF47; Fig. S4A) also resulted in marked paraspeckle disintegration in ∼70% of cells (Fig. 3 A and B). Based on these data, we propose that components of intact paraspeckle-localized SWI/SNF complexes are involved in the formation of paraspeckles.

Fig. 3.

SWI/SNF complexes are essential for paraspeckle formation. (A) The effects of RNAi-mediated knockdown of the indicated SWI/SNF components on paraspeckle formation. The effects were monitored by analyzing paraspeckle integrity by using RNA FISH detection of NEAT1 and immunofluorescent detection of PSPC1. The siRNAs used in these experiments are listed in Table S3. Because BRG1 and BRM are functionally redundant, these proteins were concomitantly knocked down with a combination of two siRNAs (BRG1#2/BRM#1 and BRG1#4/BRM#2). The results of single RNAi-mediated knockdown of BRG1 or BRM are shown in Fig. S3. (Scale bars: 10 μm.) (B) Quantification of the number of paraspeckle-positive cells after RNAi-mediated knockdown of the indicated SWI/SNF components (as shown in A). Data are represented as the mean ± SD of three replicates. The cell numbers for the control, BRG1#2/BRM#1, BRG1#4/BRM#2, BAF170, BAF155, BAF57, and BAF47 groups were 435, 229, 266, 165, 149, 198, and 227, respectively (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.02 by Student t test). (C) The lack of paraspeckles in adrenal cortex adenocarcinoma SW13 cells (Upper). RNA FISH was used to detect NEAT1, and immunocytochemistry was used to detect RBM14 in SW13 and HeLa (control) cells. (Scale bars: 10 μm.) Nuclear speckles in SW13 cells as detected by RNA FISH analyses of MALAT1 and immunofluorescent analyses of SRSF2 (Lower). (Scale bars: 10 μm.) (D) Paraspeckle formation does not require the canonical nucleosome-remodeling activity of SWI/SNF complexes. Schematic representations of WT and two ATPase mutants (M1 and M2) of BRG1 are shown on the left. HAP1 cells were treated with siBRM to abolish the background expression of BRM. The essential lysine residue (marked as “K”) in WT BRG1 and the artificially inserted proline residue (marked as “P”) in the M2 mutant are shown in red and blue, respectively. The paraspeckles detected in WT, M1, and M2 HAP1 cells are shown on the right. (Scale bar: 10 μm.)

In SW13 cells, SWI/SNF complexes are undetectable as a result of silencing of both BRG1 and BRM (Fig. S5A) (19). When we examined these cells, we observed normal nuclear speckles but no paraspeckle-like nuclear foci (Fig. 3C). In addition, immunoblot analyses and RNase protection assays (RPAs) of SW13 cells revealed the accumulation of essential PSPs and NEAT1, respectively (Fig. S5 A and B). This result supports the hypothesis that paraspeckle formation specifically requires SWI/SNF complexes.

To investigate the requirement of the remodeling activity of SWI/SNF complexes for paraspeckle formation, the CRISPR/Cas9 system was used to create small deletions of the catalytic subunit BRG1 that spanned the most classically characterized essential lysine residue (K785) in the ATPase domain (20) (M1 and M2 in Fig. 3D, Left). To accelerate genomic engineering, we used the near-haploid human HAP1 cell line, in which we detected marginal expression of BRM (Fig. S6A), suggesting that paraspeckle formation depends on BRG1 without the functional redundancy of BRM. Paraspeckle formation was abolished by RNAi-mediated knockdown of BRG1 in HAP1 cells, but was barely affected by knockdown of BRM (Fig. S6B). Although the ATPase M1 and M2 mutations moderately diminished the expression level of BRG1 in HAP1 cells (Fig. S6C), both mutant proteins were properly localized and sustained the paraspeckle structure (Fig. 3D, Right). The size and number of paraspeckles were not altered in the M1 and M2 mutant cells (Fig. 3D, Right). We also confirmed that the ATPase mutations abrogated the canonical chromatin-remodeling function of the SWI/SNF complexes in the IFN-γ–dependent transcriptional activation of the class II transactivator (CIITA) gene (21) (Fig. S6D). Taken together, these data indicate that the canonical ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling activity of BRG1 is not required for paraspeckle formation.

SWI/SNF Complexes Facilitate the Formation of a PSP Interaction Network in Paraspeckles.

To determine what is defective in SWI/SNF-depleted cells (ΔSWI/SNF cells) for paraspeckle formation, we measured the expression of known essential paraspeckle components, including NEAT1_2 and category 1 PSPs. RPAs were used to determine whether the paraspeckle disintegration observed in ΔSWI/SNF cells was caused by diminished accumulation of NEAT1_2. These analyses, which were performed by using an antisense riboprobe that discriminated between the two NEAT1 isoforms, revealed no loss in the expression of NEAT1 isoforms in ΔSWI/SNF cells (Fig. S4B). It is noteworthy that the NEAT1_1 level was higher in ΔSWI/SNF cells, and consequently the ratio between NEAT1 isoforms was altered (Fig. S4B). Furthermore, immunoblot analyses showed that seven essential PSPs (14) were constantly accumulated in ΔSWI/SNF cells (Fig. S4C). These results indicate that paraspeckle disintegration in ΔSWI/SNF cells was not caused by the down-regulation of known essential paraspeckle components.

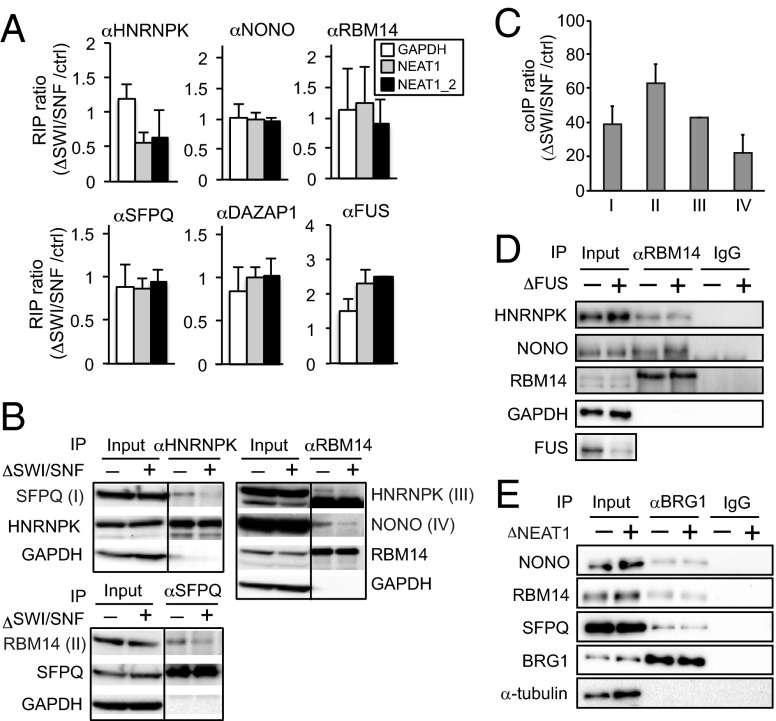

In the absence of SWI/SNF complexes, paraspeckle formation was arrested despite the continued accumulation of NEAT1_2. To examine the defective process of paraspeckle formation in ΔSWI/SNF cells further, we examined the intermolecular interactions between essential paraspeckle components. RNA IP experiments showed that the interactions between NEAT1 and category 1 PSPs were unaffected in ΔSWI/SNF cells. An exception was the interaction between NEAT1 and HNRNPK, which was ∼50% lower in ΔSWI/SNF cells than in control cells (Fig. 4A). The lower interaction between NEAT1 and HNRNPK may be a consequence of the change in the NEAT1 isoform ratio shown in Fig. S4B (14). However, co-IP analyses of category 1A proteins showed that the interactions between category 1A proteins (HNRNPK-SFPQ, RBM14-HNRNPK, RBM14-NONO, and SFPQ-RBM14) were significantly diminished in ΔSWI/SNF cells (Fig. 4 B and C). To determine whether the decreased interactions between PSPs in ΔSWI/SNF cells were a consequence of paraspeckle structural disintegration, the interactions between PSPs were monitored in cells in which paraspeckle formation was blocked by depletion of FUS (a category 1B protein) (14). Knockdown of FUS had no effect on the interactions between RBM14 and other category 1A proteins (Fig. 4D). Taken together, these results suggest that the decreased interactions between PSPs in ΔSWI/SNF cells are caused by the loss of specific SWI/SNF complex functions required for paraspeckle formation. Next, we monitored interactions between SWI/SNF components and essential PSPs in ΔNEAT1 cells that lacked paraspeckles. The interactions between BRG1 and three essential PSPs were not affected by NEAT1 depletion (Fig. 4E), indicating that the interactions between proteins in SWI/SNF complexes and PSPs is not dependent on paraspeckle integrity.

Fig. 4.

SWI/SNF complexes are required for proper interactions between PSPs. (A) RNA IP of NEAT1 with six essential PSPs from control and ΔSWI/SNF cells. The amounts of immunoprecipitated RNAs were quantified by quantitative RT-PCR using the NEAT1 and NEAT1_2 primer pairs shown in Table S2. The ratio of immunoprecipitated RNA from ΔSWI/SNF cells to that from the control cells was calculated. The expression level of GAPDH was measured as a control. Data are represented as the mean ± SD of three replicates. (B and C) Interactions between the essential PSPs in control (−) and ΔSWI/SNF (+) cells. Co-IP was performed by using antibodies against HNRNPK, RBM14, and SFPQ, and the expression levels of the indicated PSPs were monitored by immunoblotting (B). The interactions that were diminished by <40% in ΔSWI/SNF cells are indicated by I–IV, and the quantified co-IP ratios (ΔSWI/SNF/control) in I–IV are plotted on the graph shown in C. (D) Interactions between RBM14 and essential PSPs in control (−) and paraspeckle-depleted ΔFUS (+) cells. Co-IP was performed by using an anti-RBM14 antibody, and the expression levels of the indicated PSPs were monitored by immunoblotting. (E) Interactions between BRG1 and the essential PSPs in control (−) and NEAT1-depleted (+) cells.

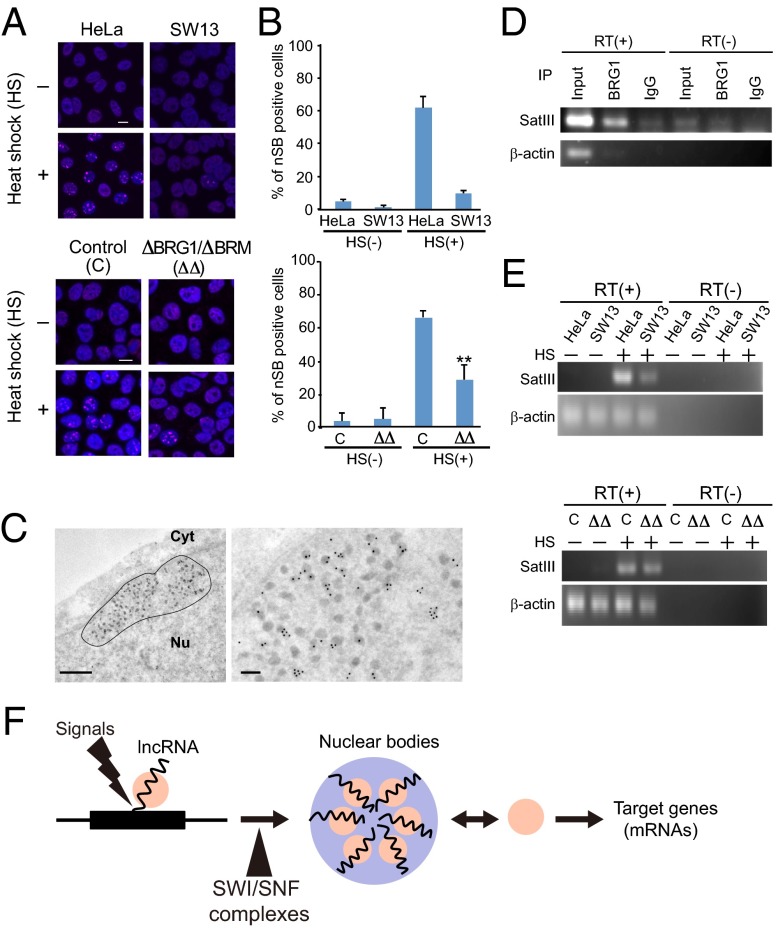

SWI/SNF Complexes Are Required for the Formation of Another lncRNA-Dependent Nuclear Body.

Nuclear stress bodies (nSBs), another type of RNA-dependent nuclear body, occur in response to heat shock in a process initiated by the synthesis of lncRNA derived from pericentric tandem repeats of Satellite III (Sat III) sequences (22). Sat III lncRNA sequesters several splicing-related factors, such as serine/arginine-rich splicing factor 1 and scaffold attachment factor B (SAFB) (22). To determine whether SWI/SNF complexes are required for Sat III lncRNA-dependent formation of nSBs, the numbers of nSB-positive control HeLa cells, ΔBRG1/ΔBRM HeLa cells, and SW13 cells lacking functional SWI/SNF complexes were determined before and after heat shock at 42 °C for 1 h. The formation of nSBs in response to heat shock was impaired in ΔBRG1/ΔBRM HeLa cells and SW13 cells (Fig. 5 A and B and Fig. S5C). In addition, an I-EM analysis revealed localization of BRG1 in the electron-dense granules of nSBs (Fig. 5C), supporting the involvement of SWI/SNF complexes in nSB formation. RNA IP with an αBRG1 antibody revealed the association of BRG1 with heat-shock–induced Sat III lncRNA (Fig. 5D); however, the expression of Sat III lncRNA was still detected in ΔBRG1/ΔBRM HeLa cells and SW13 cells (Fig. 5E). These data indicate that SWI/SNF complexes contribute to the assembly of nSBs by interacting with Sat III lncRNA, a role that is remarkably similar to their role in paraspeckle formation. Taken together, these results raise the possibility that SWI/SNF complexes are part of a common mechanism for the lncRNA-dependent formation of two distinct nuclear bodies (Fig. 5F).

Fig. 5.

SWI/SNF complexes are required for the formation of nSBs. (A) Immunostaining of scaffold attachment factor B (magenta) to detect the formation of nSBs before and after heat shock (HS) of control HeLa cells, SW13 cells, and BRG1/BRM-specific siRNA-treated HeLa cells. (Scale bars: 10 μm.) (B) Quantification of the numbers of nSB-positive cells shown in A. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of three replicates. The cell numbers for HeLa(HS−), SW13(HS−), HeLa(HS+), SW13(HS+), C(HS−), ΔBRG1/ΔBRM(HS−), C(HS+), and ΔBRG1/ΔBRM(HS+) groups were 276, 228, 303, 202, 341, 356, 332, and 403, respectively (**P < 0.02 by Student t test). (C) I-EM detection of BRG1 in nSBs. Dashed line (Left) indicates a single nSB. (Scale bars: Left, 0.5 μm; Right, 100 nm.) (D) RNA IP of Sat III lncRNA from heat-shock–treated HeLa cells using the αBRG1 antibody. The expression level of β-actin was used as a control. RT, reverse transcription. The sequences of the PCR primers used are shown in Table S2. (E) RT-PCR analyses of Sat III lncRNA expression in control HeLa cells, SW13 cells, and BRG1/BRM-specific siRNA-treated HeLa cells. HS, heat shock at 42 °C for 1 h. (F) A model of lncRNA-dependent nuclear body assembly. SWI/SNF complexes may be common assembly factors in mammalian cells. Nuclear bodies act to sequestrate specific regulatory proteins to control the expression of specific genes (9).

Discussion

In this paper, we demonstrate that subunits of SWI/SNF complexes are localized to paraspeckles, where they play an essential role in the formation of these cellular structures. The canonical ATP-dependent nucleosome remodeling activity of SWI/SNF complexes is not required for this role. In a number of previous studies, immunofluorescent analyses revealed a broad distribution of human SWI/SNF components (BRG1 and BRM) throughout the nucleoplasm (e.g., refs. 23, 24), which is in contrast to our observations. We suggest that the different fixation conditions (use of ethanol and acetone) used in this study (Fig. S1A) or the use of RNA FISH (Figs. 1 and 3) improved the detection of BRG1 in paraspeckles by immunostaining. We can argue for the paraspeckle localization of SWI/SNF complexes based on the following data: (i) immunofluorescent signals of BRG1 were detected in paraspeckles and were lost upon knockdown of BRG but not BRM, (ii) the paraspeckle localization of BRG1 was confirmed by using two distinct antibodies against BRG1, (iii) five other SWI/SNF subunits were localized to paraspeckles, and (iv) SWI/SNF components physically interacted with NEAT1 and PSPs.

The results of the I-EM study also showed a marked enrichment of SWI/SNF components within paraspeckles; in particular, a characteristic patchy pattern of distribution in the interior region was observed. The 5′ and 3′ terminal regions and the middle region of NEAT1_2 are located mainly in the periphery and interior of paraspeckles, respectively (8). No other PSPs exhibited a similar patchy localization pattern, indicating that it was unique to SWI/SNF components.

The I-EM study revealed the depletion of chromatin in SWI/SNF-located paraspeckle subdomains, suggesting that SWI/SNF complexes are localized to paraspeckles because they interact with NEAT1 and PSPs, and not with the chromosomes. Similarly, SWI/SNF complexes, not chromosomes, may dictate the proper locations of NEAT1 and other PSPs within the paraspeckle structure. This proposal is consistent with the finding that the nucleosome remodeling activity of SWI/SNF complexes is not required for their function in paraspeckle formation, and suggests that these complexes act as a part of the structural foundation of paraspeckles.

The evidence that SWI/SNF components (BRG1 and BRM) interact directly with NEAT1, as well as with a number of the essential PSPs, supports the pivotal functionality of the SWI/SNF components in sustaining paraspeckle structure. A recent study demonstrated that BRG1 binds to a specific lncRNA, termed Myheart, which acts to antagonize BRG1 function (25). The SWI/SNF component hSNF5 interacts with a specific lncRNA termed SChLAP1, which arrests the chromosome association of SWI/SNF complexes (26). Taken together, these findings suggest that some components of SWI/SNF complexes have affinity for lncRNAs.

According to our previous reports, paraspeckle formation involves at least two distinct steps: (i) NEAT1_2 expression by category 1A proteins and (ii) paraspeckle assembly by category 1B proteins that do not affect the NEAT1_2 expression level (14). In ΔSWI/SNF cells, paraspeckle formation was defective despite NEAT1_2 accumulation, confirming that SWI/SNF complexes are involved in the second assembly step. SWI/SNF depletion resulted in a marked loss of protein–protein interactions between essential PSPs, but these interactions were not affected by knockdown of FUS, a category 1B protein. Taken together, these results suggest that SWI/SNF complexes are involved in a previously unidentified essential step of paraspeckle formation.

In mammalian cells, additional nuclear bodies constructed around specific lncRNAs have been reported (27), and nSB foci form on stress-induced Sat III lncRNA in response to heat shock. SWI/SNF complexes are localized in nSBs, where they interact with Sat III lncRNA. Depletion of SWI/SNF complexes impaired the formation of nSBs in response to heat shock without affecting the level of Sat III lncRNA, suggesting that these complexes are involved in the assembly of Sat III sub-RNP complexes. The mechanism involved may be similar to that of SWI/SNF-dependent paraspeckle assembly. Paraspeckles and nSBs sequestrate specific sets of RNA-binding proteins whose specificity is defined by RNA sequence elements that reside in the lncRNAs. Similar to paraspeckles, nSBs form on the locus where Sat III lncRNA is transcribed; therefore, it is intriguing to hypothesize that SWI/SNF complexes bridge the architectural lncRNA to the sequestered RNA-binding protein to construct huge RNP complexes at the cognate chromosomal locus. Further characterization of the modes of action of SWI/SNF complexes will help unveil the common mechanisms underlying the lncRNA-dependent formation of nuclear bodies.

Materials and Methods

Basic methods for techniques such as RPA, quantitative RT-PCR, and immunoblotting are described in SI Materials and Methods.

Cell Culture.

HeLa, A549, HEK293, NIH 3T3, and SW13 cells were grown and maintained as described previously (14). HAP1 cells were purchased from Haplogen and cultured in Iscove modified Dulbecco medium (IMDM). For heat-shock experiments, the cells were incubated for 1 h at 42 °C and then allowed to recover for 1 h at 37 °C. Some cells were treated with actinomycin D (0.3 μg/mL) for 4 h or MG132 (5 μM) for 17 h.

RNA FISH and Immunocytochemistry.

The RNA FISH probes were synthesized by using SP6 RNA polymerase and a DIG/FITC RNA labeling kit (Roche Diagnostic). Linearized plasmids (1 μg) containing a NEAT1 fragment (+1 to +1,000) or a MALAT1 fragment (+5,114 to +5,712) were used as templates for transcription. RNA FISH and immunocytochemical analyses were performed as described previously (14). The detailed conditions are described in SI Materials and Methods.

IP of RNP Complexes.

HeLa cells were lysed with IP lysis buffer [50 mM Tris⋅HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 20 U/mL SUPERase•In (Ambion), complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor, and PhoSTOP phosphatase inhibitor] and then disrupted by three pulses of sonication for 5 s. The cell extracts were incubated with or without RNase A (1 μg/mL) or ethidium bromide (50 μg/mL) on ice for 30 min, and then cleared by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The antibodies were incubated with Dynabeads Protein-G, Dynabeads anti-rabbit IgG, or Dynabeads anti-mouse IgG (Life Technologies) for 1 h and then washed five times with IP lysis buffer. The remaining supernatants were mixed with the antibody–bead conjugates and rotated at 4 °C for 3 h or overnight, after which the beads were washed three times with IP lysis buffer. For cross-linking IP, 1.8 J/cm2 UV light was used for irradiation, as described previously (6). The antibodies used are listed in Table S1.

CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Genome Engineering.

The guide RNA in the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)/Cas9 system was designed using the CRISPR design tool (crispr.mit.edu/) and then cloned into the BbsI site of the PX459 vector (Addgene plasmid ID 48141). HAP1 cells were transfected with the guide RNA plasmid by using Nucleofection reagent (Lonza). For clonal selection of the mutants, the cells were selected in IMDM containing 167 ng/mL of puromycin for 2 d, and then diluted and incubated in IMDM without puromycin in 96-well plates. The selected clones were lysed, and the genomic region flanking the CRISPR target site was amplified by PCR to check for the presence of small deletions, which were confirmed by sequencing. The primers used are listed in Table S2.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Y. Ikeuchi and the members of the laboratory of T.H. for useful discussions. This research was supported by the Funding Program for the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan, as well as by grants from the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization, the Mitsubishi Foundation, the Takeda Science Foundation, the Suminoto Foundation, the Naito Foundation, and the Mochida Memorial Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1423819112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Visa N, Puvion-Dutilleul F, Bachellerie JP, Puvion E. Intranuclear distribution of U1 and U2 snRNAs visualized by high resolution in situ hybridization: Revelation of a novel compartment containing U1 but not U2 snRNA in HeLa cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 1993;60(2):308–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fox AH, et al. Paraspeckles: A novel nuclear domain. Curr Biol. 2002;12(1):13–25. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00632-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox AH, Bond CS, Lamond AI. P54nrb forms a heterodimer with PSP1 that localizes to paraspeckles in an RNA-dependent manner. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(11):5304–5315. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-06-0587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prasanth KV, et al. Regulating gene expression through RNA nuclear retention. Cell. 2005;123(2):249–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clemson CM, et al. An architectural role for a nuclear noncoding RNA: NEAT1 RNA is essential for the structure of paraspeckles. Mol Cell. 2009;33(6):717–726. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sasaki YT, Ideue T, Sano M, Mituyama T, Hirose T. MENepsilon/beta noncoding RNAs are essential for structural integrity of nuclear paraspeckles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(8):2525–2530. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807899106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sunwoo H, et al. MEN epsilon/beta nuclear-retained non-coding RNAs are up-regulated upon muscle differentiation and are essential components of paraspeckles. Genome Res. 2009;19(3):347–359. doi: 10.1101/gr.087775.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Souquere S, Beauclair G, Harper F, Fox A, Pierron G. Highly ordered spatial organization of the structural long noncoding NEAT1 RNAs within paraspeckle nuclear bodies. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21(22):4020–4027. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-08-0690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirose T, et al. NEAT1 long noncoding RNA regulates transcription via protein sequestration within subnuclear bodies. Mol Biol Cell. 2014;25(1):169–183. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-09-0558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imamura K, et al. Long noncoding RNA NEAT1-dependent SFPQ relocation from promoter region to paraspeckle mediates IL8 expression upon immune stimuli. Mol Cell. 2014;53(3):393–406. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakagawa S, et al. The lncRNA Neat1 is required for corpus luteum formation and the establishment of pregnancy in a subpopulation of mice. Development. 2014;141(23):4618–4627. doi: 10.1242/dev.110544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Standaert L, et al. The long noncoding RNA Neat1 is required for mammary gland development and lactation. RNA. 2014;20(12):1844–1849. doi: 10.1261/rna.047332.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mao YS, Sunwoo H, Zhang B, Spector DL. Direct visualization of the co-transcriptional assembly of a nuclear body by noncoding RNAs. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(1):95–101. doi: 10.1038/ncb2140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naganuma T, et al. Alternative 3′-end processing of long noncoding RNA initiates construction of nuclear paraspeckles. EMBO J. 2012;31(20):4020–4034. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakagawa S, Naganuma T, Shioi G, Hirose T. Paraspeckles are subpopulation-specific nuclear bodies that are not essential in mice. J Cell Biol. 2011;193(1):31–39. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201011110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson BG, Roberts CW. SWI/SNF nucleosome remodellers and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(7):481–492. doi: 10.1038/nrc3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phelan ML, Sif S, Narlikar GJ, Kingston RE. Reconstitution of a core chromatin remodeling complex from SWI/SNF subunits. Mol Cell. 1999;3(2):247–253. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80315-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai JS, Herr W. Ethidium bromide provides a simple tool for identifying genuine DNA-independent protein associations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89(15):6958–6962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.6958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito T, et al. Brm transactivates the telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) gene and modulates the splicing patterns of its transcripts in concert with p54(nrb) Biochem J. 2008;411(1):201–209. doi: 10.1042/BJ20071075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khavari PA, Peterson CL, Tamkun JW, Mendel DB, Crabtree GR. BRG1 contains a conserved domain of the SWI2/SNF2 family necessary for normal mitotic growth and transcription. Nature. 1993;366(6451):170–174. doi: 10.1038/366170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ni Z, Abou El Hassan M, Xu Z, Yu T, Bremner R. The chromatin-remodeling enzyme BRG1 coordinates CIITA induction through many interdependent distal enhancers. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(7):785–793. doi: 10.1038/ni.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biamonti G, Vourc’h C. Nuclear stress bodies. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(6):a000695. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reyes JC, Muchardt C, Yaniv M. Components of the human SWI/SNF complex are enriched in active chromatin and are associated with the nuclear matrix. J Cell Biol. 1997;137(2):263–274. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ishida M, Tanaka S, Ohki M, Ohta T. Transcriptional co-activator activity of SYT is negatively regulated by BRM and Brg1. Genes Cells. 2004;9(5):419–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1356-9597.2004.00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han P, et al. A long noncoding RNA protects the heart from pathological hypertrophy. Nature. 2014;514(7520):102–106. doi: 10.1038/nature13596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prensner JR, et al. The long noncoding RNA SChLAP1 promotes aggressive prostate cancer and antagonizes the SWI/SNF complex. Nat Genet. 2013;45(11):1392–1398. doi: 10.1038/ng.2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hirose T, Mishima Y, Tomari Y. Elements and machinery of non-coding RNAs: toward their taxonomy. EMBO Rep. 2014;15(5):489–507. doi: 10.1002/embr.201338390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.