Abstract

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) afflict approximately half of HIV-infected patients. The HIV-1 transactivator of transcription (Tat) protein is released by infected cells and contributes to the pathogenesis of HAND, but many of the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood. Here we used fura-2-based Ca2+ imaging and whole-cell patch-clamp recording to study the effects of Tat on the spontaneous synaptic activity that occurs in networked rat hippocampal neurons in culture. Tat triggered aberrant network activity that exhibited a decrease in the frequency of spontaneous action potential bursts and Ca2+ spikes with a simultaneous increase in burst duration and Ca2+ spike amplitude. These network changes were apparent after 4 h treatment with Tat and required the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP). Interestingly, Tat-induced changes in network activity adapted during 24 h exposure. The activity returned to control levels in the maintained presence of Tat for 24 h. These observations indicate that Tat causes aberrant network activity, which is dependent on LRP, and adapts following prolonged exposure. Changes in network excitability may contribute to Tat-induced neurotoxicity in vitro and seizure disorders in vivo. Adaptation of neural networks may be a neuroprotective response to the sustained presence of the neurotoxic protein Tat and could underlie the behavioral and electrophysiological changes observed in HAND.

Keywords: adaptation, Ca2+ signaling, excitotoxicity, HIV associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND), lipoprotein receptor, synaptic network, hippocampal culture, fura-2

Introduction

HIV associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) afflict approximately half of HIV infected patients [1]. Functional loss in HAND ranges from subclinical deficits to a dementia that disrupts even simple tasks of daily living [2]. The severity of functional impairment correlates with synaptodendritic damage [3]. As might be predicted for patients undergoing viral driven synaptic changes, HIV infected patients exhibit abnormal electroencephalographic (EEG) rhythms and an increased incidence of seizures [4, 5], suggesting functional changes in synaptic networks.

HIV does not infect neurons; thus, the neurotoxicity produced by HIV in the brain is indirect and results from shed HIV proteins, secreted inflammatory cytokines and released excitotoxins [6]. While all of these factors likely act together to produce synaptic damage, a significant contributor is the HIV protein Tat [7]. Elevated levels of Tat are found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of virologically controlled HIV patients on antiretroviral therapy, presumably because expression of Tat continues in the presence of antiviral drugs after HIV DNA is integrated into the host genome [8]. Antibodies to Tat may be neuroprotective as the levels of anti-Tat antibodies in the CSF of HIV infected patients are inversely correlated with HAND severity [9]. Transgenic animals that express Tat in the brain exhibit synapse loss and impaired cognitive function [10, 11]. In vitro studies have shown that Tat potentiates NMDA receptor function [12–14] leading to loss of excitatory synapses [15], increased inhibitory synapses [16] and, following prolonged exposure, neuronal death [17].

The synaptic changes produced by Tat appear to be a coping mechanism, somewhat analogous to homeostatic plasticity [18]. Here, we examined the effects of Tat on the spontaneous synaptic activity that occurs in networked hippocampal neurons in culture. We hypothesized that Tat would alter network activity and that the effects would change during prolonged exposure. We report that exposure to Tat for 4 h decreased the frequency of action potential bursts and spontaneous Ca2+ spikes while simultaneously increasing burst duration and Ca2+ spike amplitude. By 24 h these changes had abated indicating that the network adapted to the presence of the HIV protein. We speculate that Tat-induced network changes adapt as a result of previously described synaptic adaptations and may underlie the behavioral and electrophysiological changes observed in HAND.

Materials and Experimental Methods

Drugs and Reagents

Materials were obtained from the following sources: HIV-1 Tat (Clade B, 1–86 amino acids) was acquired from Prospec Tany TechnoGene Ltd. (Rehovot, Israel); Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum, horse serum, and fura-2-acetoxymethyl ester (Fura-2-AM) were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA); recombinant rat low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein associated protein 1 (RAP) was purchased from Fitzgerald Industries International (Concord, MA).

Cell Culture

In accordance with the University of Minnesota’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the NIH guide for the care and use of laboratory animals, maternal rats were euthanized by CO2 inhalation and fetuses were removed on embryonic day 17. Rat hippocampal neurons were grown in primary culture as described previously [19]. Cells used in these experiments were cultured without mitotic inhibitors for 12 to 15 days in vitro (DIV) resulting in a mixed glial-neuronal culture consisting of 18 ± 2% neurons, 70 ± 3% astrocytes, and 9 ± 3% microglia as indicated by immunocytochemistry [20].

Electrophysiology

Spontaneous bursts of action potentials were recorded in the whole-cell current-clamp configuration. Electrodes were pulled using a horizontal micropipette puller (P-87; Sutter Instruments) from glass capillaries (Narishige). Pipettes had resistances of 3–5 MΩ when filled with the following intracellular recording solution (in mM): 130 K-Gluconate, 10 KCl, 10 NaCl, 10 BAPTA, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, 5 MgATP, and 0.3 NaGTP (pH was adjusted to 7.2 with KOH; osmolarity was 300 mOsm). Recordings were performed with the following extracellular solution (in mM): 143 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1.3 CaCl, 0.9 MgCl, 20 HEPES, and 5 glucose (pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH; osmolarity was adjusted to 305 mOsm with sucrose) (slightly modified from [21]). Whole-cell voltages were amplified with an AxoPatch 200B (Molecular Devices), low-pass filtered at 2 kHz, and digitized at 10 kHz with a Digidata 1322A digitizer with pClamp software (Molecular Devices). If needed, current was injected to keep cells at −60 mV for the duration of the recording. Cells with a membrane resistance >300 MΩ and an access resistance <20 MΩ were used for analysis. Burst frequency and duration were analyzed using pClamp software. Patch-clamp experiments were performed in parallel to Ca2+ imaging experiments and were taken from the same plating’s of neurons.

[Ca2+]i imaging

Intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) was recorded using fura-2-based digital imaging as previously described [22]. Fluorescent intensity values (340 nm/380 nm excitation) were converted to [Ca2+]i using previously reported calibration constants [23].

Statistical analysis

For electrophysiology studies, an individual experiment was defined as the action potential frequency or duration recorded from a single neuron. Each experiment was replicated using at least 11 neurons from at least 3 cultures. Changes in burst frequency and duration are presented as mean ± SEM. For [Ca2+]i recordings, the neuronal cell body was selected as the region of interest for all measurements. Every neuron within an imaging field was included in the analysis and no exclusions were made. The frequency of calcium spikes was synchronized for the neurons within a field of view on a coverglass; thus, an individual experiment (n=1) was defined as the number of Ca2+ spikes per 10 min epoch recorded from a single field of view (FOV) on a coverglass. Each experiment was replicated using between 7 and 14 coverglasses from at least 2 separate cultures. The amplitude of calcium spikes is varies dramatically between individual neurons within a FOV on a coverslip; thus, an individual experiment (n=1) was defined as the change in [Ca2+]i resulting from a single Ca2+ spike from a single neuron. Each experiment was replicated using between 198 and 336 neurons from at least 2 separate cultures. Changes in spike frequency and [Ca2+]i are presented as mean ± SEM. Significant differences were determined using Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons.

Results

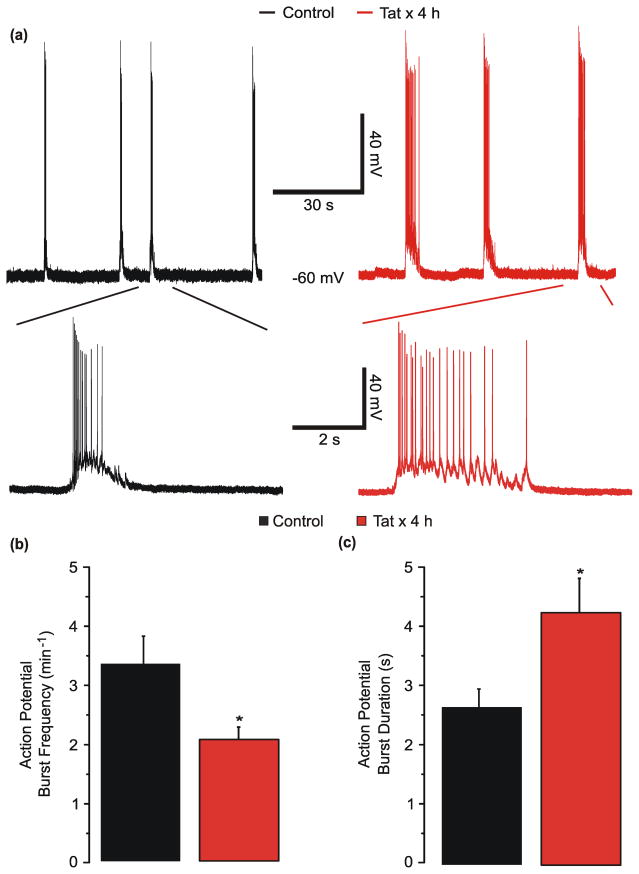

Tat reduces action potential burst frequency and increases burst duration

Acute exposure to the HIV protein Tat increases the excitability of neurons [24–27]. Tat concentrations as high as 40 ng/mL have been detected in the sera of HIV-infected patients [28]. Changes in NMDAR function [12] and synaptic composition [15, 16] occur following prolonged exposure to 50 ng/mL Tat. Thus, we hypothesized that prolonged exposure to 50 ng/mL Tat would alter the spontaneous activity observed in the synaptic network that forms between rat hippocampal neurons in culture (DIV 12–15) [29–32]. To test this hypothesis, the whole-cell current clamp technique was used to record membrane potential from control neurons and neurons treated with 50 ng/mL Tat for 4 h (Fig. 1a). Treatment with Tat simultaneously decreased the frequency of spontaneous bursts of action potentials (Fig. 1b) and increased the burst duration (Fig. 1c). The action potential burst frequency decreased by 38 % from 3.4 ± 0.5 to 2.1 ± 0.2 min−1. The burst duration increased by 61 % from 2.6 ± 0.3 to 4.2 ± 0.6 s.

Fig. 1. Tat reduces action potential burst frequency and increases burst duration.

a, Representative traces show bursts of action potentials, under whole-cell current-clamp mode, during a 90 s sweep from an untreated (⚊) neuron or from a neuron treated with 50 ng/mL Tat (

) for 4 h. Insets show individual bursts of action potentials displayed on an expanded time scale. b–c, Bar graphs show frequency (b) or duration (c) of action potential bursts from cultures left untreated (■, n=12) or treated with Tat (

) for 4 h. Insets show individual bursts of action potentials displayed on an expanded time scale. b–c, Bar graphs show frequency (b) or duration (c) of action potential bursts from cultures left untreated (■, n=12) or treated with Tat (

, n=11) for 4 h. *p<0.05 relative to control as determined by Student’s t-test.

, n=11) for 4 h. *p<0.05 relative to control as determined by Student’s t-test.

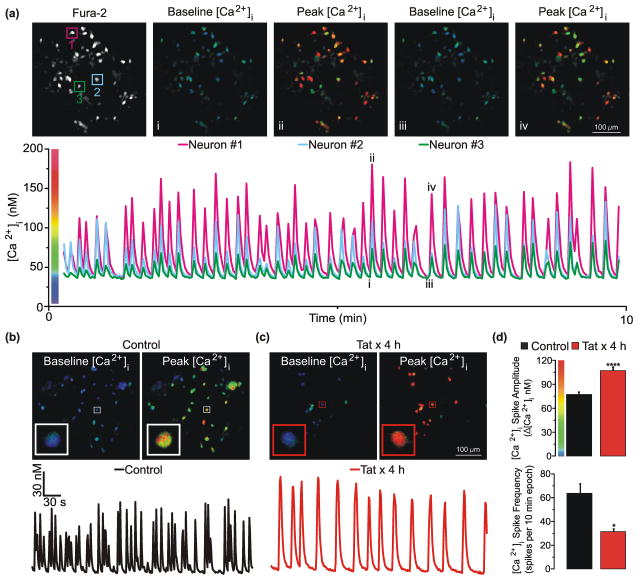

Tat reduces spontaneous [Ca2+]i spike frequency and increases [Ca2+]i spike amplitude

Each burst of action potentials, such as those described in Fig. 1, produces an increase in [Ca2+]i ([Ca2+]i spike) that increases in amplitude with increasing burst duration [33]. Because fura-2-based digital [Ca2+]i imaging enables the rapid and reliable recording of [Ca2+]i spikes, even from hippocampal networks exposed to neurotoxins, we used [Ca2+]i spike recording to assess the time course and mechanism of Tat effects on synaptic function. Considering that Tat reduced the frequency and increased duration of action potential bursts, we hypothesized that Tat would reduce the frequency and increase the amplitude of [Ca2+]i spikes. To test this hypothesis, spontaneous [Ca2+]i spiking was monitored in fields of approximately 20 rat hippocampal neurons using fura-2-based digital imaging (Fig. 2a). Neurons were superfused with HHSS for 3 min and then activity was assessed during a 10 min imaging epoch. A [Ca2+]i spike was defined as an increase in [Ca2+]i of ≥10 nM relative to the preceding baseline (for complex spikes the inflection point was defined as baseline). Consistent with our hypothesis, treatment with Tat for 4 h reduced the frequency of [Ca2+]i spikes and increased their amplitude relative to neurons left untreated (Fig b-d). Resting [Ca2+]i was similar in control (42 ± 1nM) and Tat-treated cells (43 ± 1 nM). To determine if the observed effects were specific to Tat, primary neuronal cultures were left untreated (n=8 coverslips) or treated for 4 h with either 50 ng/mL of heat-inactivated (HI)-Tat (85°C x 30 min, n=8) or Tat (n=8). Network activity was similar between untreated cultures (17 ± 3 spikes per 10 min) and cultures treated with heat-inactivated Tat (21 ± 3 spikes per 10 min). However, [Ca2+]i spike frequency was significantly lower (p<0.05) in cultures treated with Tat (11 ± 2 spikes per 10 min) relative to HI-Tat as determined by an ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test for multiple comparisons. Taken together, these data indicate that treatment with Tat for 4 h reduces spontaneous Ca2+ spike frequency and increases Ca2+ spike amplitude.

Fig. 2. Tat reduces spontaneous [Ca2+]i spike frequency and increases [Ca2+]i spike amplitude.

a, Representative images show a region of fura-2 loaded neurons at baseline [Ca2+]i (i, iii) and during the peak of a [Ca2+]i spike (ii, iv). Pseudocolor images (i–iv) correspond to the numerals in the representative trace below. Pseudocolor images are scaled as indicated by the color bar on the y-axis of the plot. Note that neuronal processes lie below the focal plane in these images. Representative traces from the neurons identified in the representative Fura-2 fluorescence intensity image shows synchronized [Ca2+]i spike frequency during a 10 minute imaging epoch. b, c Representative pseudocolor images show a region of untreated (control) neurons or neurons treated for 4 h with 50 ng/mL of Tat (Tat x 4 h) at baseline [Ca2+]i and during the peak of a [Ca2+]i spike. Representative traces from the neurons identified by the boxed region in b and c show spontaneous [Ca2+]i spiking during a 10 min imaging epoch from untreated (b, control ⚊) and Tat-treated (c, Tat x 4 h

), neurons. Insets show enlarged image of the soma from neurons identified by the boxed region in b and c (see Supplemental Video #1). d, Bar graphs show [Ca2+]i spike amplitude (top: n=256 and 198 neurons for control and Tat, respectively) and [Ca2+]i spike frequency (bottom: n=7 and 8 coverslips of neurons for control and Tat, respectively) from untreated (■) cultures or cultures treated with Tat (

), neurons. Insets show enlarged image of the soma from neurons identified by the boxed region in b and c (see Supplemental Video #1). d, Bar graphs show [Ca2+]i spike amplitude (top: n=256 and 198 neurons for control and Tat, respectively) and [Ca2+]i spike frequency (bottom: n=7 and 8 coverslips of neurons for control and Tat, respectively) from untreated (■) cultures or cultures treated with Tat (

) for 4 h. *p<0.05; ****p<0.0001 relative to control as determined by Students t-test.

) for 4 h. *p<0.05; ****p<0.0001 relative to control as determined by Students t-test.

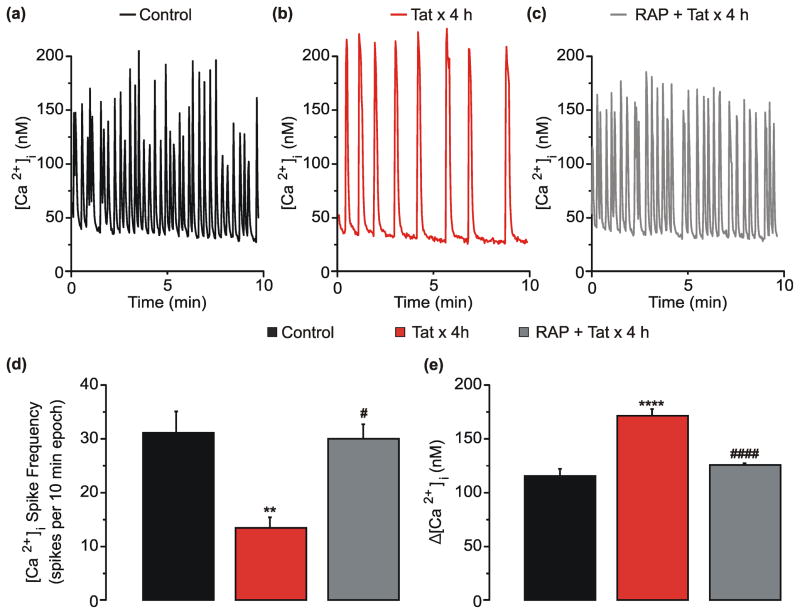

Tat-induced network changes require low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein

The low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP) binds to and internalizes Tat [34] resulting in NMDAR potentiation [12], loss of excitatory synapses [15] and, following prolonged exposure (>48 h), cell death [17]. These events are blocked by pretreatment with 50 nM of receptor-associated protein (RAP). RAP inhibits Tat binding to LRP and prevents the internalization of Tat [35]. Thus, we hypothesized that LRP was necessary for the Tat-induced changes in network activity described here and pretreatment with RAP would block these changes. Application of RAP 1 h prior to Tat application completely blocked the 59% decrease in [Ca2+]i spiking frequency induced by Tat (Fig. 3d). RAP also prevented the 49% increase in [Ca2+]i spike amplitude induced by Tat (3e). Additionally, resting [Ca2+]i was similar in control (45 ± 1 nM), Tat-treated cells (47 ± 1 nM), and Tat-treated cells that were pretreated with RAP (47 ± 1 nM). Thus, Tat-induced changes in network activity require LRP.

Fig. 3. Tat-induced network changes require LRP.

a–c, Representative traces show spontaneous [Ca2+]i spiking during a 10 min epoch from neurons left untreated (control ⚊), treated with Tat for 4 h (

), or pretreated with 50 nM RAP 1 h prior to treatment with Tat for 4 h (RAP + Tat

), or pretreated with 50 nM RAP 1 h prior to treatment with Tat for 4 h (RAP + Tat

). d–e, Bar graphs show [Ca2+]i spike frequency (d, n=11, 10, and 8 coverslips of neurons for control, Tat, and RAP + Tat, respectively) or net [Ca2+]i increase (e, n=265, 226, and 252 neurons for control, Tat, and RAP + Tat, respectively) from cultures left untreated (■), treated with Tat (

). d–e, Bar graphs show [Ca2+]i spike frequency (d, n=11, 10, and 8 coverslips of neurons for control, Tat, and RAP + Tat, respectively) or net [Ca2+]i increase (e, n=265, 226, and 252 neurons for control, Tat, and RAP + Tat, respectively) from cultures left untreated (■), treated with Tat (

) for 4 h, or treated with RAP + Tat (

) for 4 h, or treated with RAP + Tat (

). **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001 relative to untreated control neurons; #p<0.05, ####p<0.0001 relative to Tat x 4 h as determined by one-way ANOVA with 3 levels followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons.

). **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001 relative to untreated control neurons; #p<0.05, ####p<0.0001 relative to Tat x 4 h as determined by one-way ANOVA with 3 levels followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons.

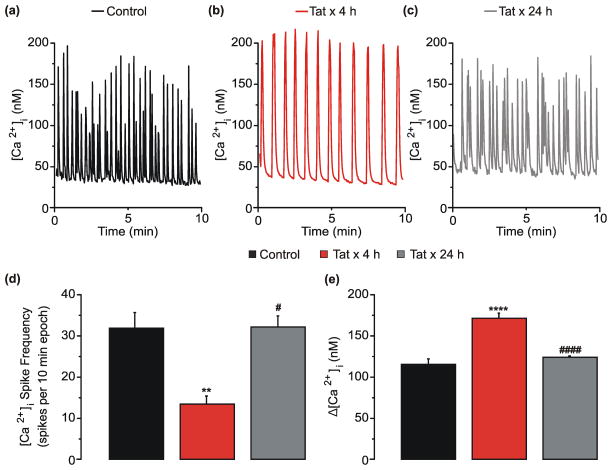

Tat-induced network changes adapt

Many of the changes in neuronal function induced by prolonged (24 h) treatment with Tat appear to be part of an adaptive response as demonstrated by an attenuation subsequent to an initial potentiation of NMDAR function [12], a loss of excitatory synapses [15] and an increase in inhibitory synapses [16]. Thus, we speculated that Tat-induced effects on network activity might also change over time. Network-mediated spontaneous [Ca2+]i spiking activity was assessed in cultures treated with Tat for 4 h or 24 h. Four h treatment with Tat reduced the frequency (Fig. 4d) and increased the amplitude of [Ca2+]i spikes (Fig. 4e). The Tat-induced decrease in [Ca2+]i spike frequency returned to control levels following 24 h exposure to Tat (Fig. 4d). The increase in [Ca2+]i spike amplitude observed following 4 h exposure to Tat also adapted back to control levels by 24 h (Fig. 4e). These adaptive responses are consistent with previously described adaptation of NMDAR function [12]. Resting [Ca2+]i was similar in control (46 ± 1nM), cells treated with Tat for 4h (47 ± 1 nM) or 24 h (46 ± 1 nM). These data suggest that Tat-mediated perturbation of network activity adapts to the sustained presence of Tat.

Fig. 4. Tat-induced network changes adapt by 24 h.

a–c, Representative traces show spontaneous [Ca2+]i spiking during a 10 min epoch from neurons left untreated (control ⚊), treated with Tat for 4 h (

), or treated with Tat for 24 h (

), or treated with Tat for 24 h (

). d–e, Bar graphs show [Ca2+]i spike frequency (d, n=14, 10, and 10 coverslips of neurons for control, Tat x 4 h, and Tat x 24 h, respectively) or net [Ca2+]i increase (e, n=323, 226, and 336 neurons for control, Tat x 4 h, and Tat x 24 h, respectively) from cultures left untreated (■), treated with Tat for 4 h (

). d–e, Bar graphs show [Ca2+]i spike frequency (d, n=14, 10, and 10 coverslips of neurons for control, Tat x 4 h, and Tat x 24 h, respectively) or net [Ca2+]i increase (e, n=323, 226, and 336 neurons for control, Tat x 4 h, and Tat x 24 h, respectively) from cultures left untreated (■), treated with Tat for 4 h (

), or treated with Tat for 24 h (

), or treated with Tat for 24 h (

). **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001 relative to untreated control; #p<0.05, ####p<0.0001 relative to Tat x 4 h as determined by one-way ANOVA with 3 levels followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons.

). **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001 relative to untreated control; #p<0.05, ####p<0.0001 relative to Tat x 4 h as determined by one-way ANOVA with 3 levels followed by Tukey’s post hoc test for multiple comparisons.

Discussion

Here, we studied the effects of Tat on spontaneous network activity in vitro. Using electrophysiological recording and digital [Ca2+]i imaging we determined that treatment with Tat for 4 h decreased the frequency of action potential bursting and spontaneous [Ca2+]i spiking. Furthermore, Tat increased the duration of action potential bursts and the amplitude of [Ca2+]i spikes. Changes in network excitability may contribute to Tat-induced neurotoxicity in vitro and seizure disorders in vivo. Tat-induced changes in network activity required LRP. This is consistent with work showing that Tat, acting via this receptor, induced changes in NMDAR function as well as the number of inhibitory and excitatory synapses [12, 15, 16]. Tat-induced network changes adapted following 24 h exposure, suggesting that the changes in synaptic function associated with HAND may result in part from an attempt to maintain homeostasis.

HIV-induced neuropathogenesis is complex and involves many factors. Tat is especially important because it is a potent neurotoxin that continues to be produced despite treatment with antiretroviral therapy [7]. Studying Tat-induced synaptic changes in vitro provides a useful model for studying network changes associated with HIV neurotoxicity. The use of a single neurotoxin in a cell culture model allows precise control of the duration and concentration of neurotoxin exposure. Furthermore, this approach enables recording from single cells and from networks of many cells simultaneously. In addition to Tat [13, 36], many HIV-associated neurotoxins, while acting through distinct upstream pathways, potentiate NMDAR mediated Ca2+ influx including: gp120 [20, 37–39], inflammatory cytokines [40, 41] and excitotoxins [42]. Thus, results obtained with Tat may extend to other neurotoxins.

Tat-induced neurotoxicity can occur via direct excitation of the neuron [25, 43] and indirectly via LRP-mediated endocytosis [17, 34]. Previous studies using this cell culture system found that LRP was required for Tat-induced NMDAR potentiation [12], loss of excitatory synapses [15], and gain of inhibitory synapses [16]. Thus, we hypothesized that LRP was required for Tat-induced changes in network activity. Consistent with our hypothesis, blockade of LRP with RAP prevented Tat-induced changes in [Ca2+]i spike frequency and amplitude. Since RAP binds with high affinity to LRP1 and other members of the LDL receptor family, actions at multiple LRPs may be involved [44]. A role for LRP in Tat-induced network changes suggests that, similar to other LRP-mediated effects of Tat, LRP might activate Src tyrosine kinase to potentiate NMDARs [12–14, 17]. NMDAR-mediated EPSPs provide a sustained depolarizing current to support bursting behavior in hippocampal neurons [45] and drive paroxysmal depolarizing shifts that produce synchronized firing in neuronal cultures [33, 46]. Thus, Tat-induced potentiation of NMDAR function would likely increase action potential burst duration and [Ca2+]i spike amplitude.

The mechanism downstream of LRP that leads to the reduced frequency of action potential bursts and [Ca2+]i spikes is unclear. Evidence suggests that Tat inhibits GABAergic and enhances glutamatergic neurotransmission leading to disinhibition and over excitation of networked neurons. Indeed, Tat decreases GABA exocytosis, while simultaneously increasing glutamate release, in human and rodent CNS tissue [47]. Similarly, in synaptosomes derived from transgenic mice expressing Tat, depolarization-evoked glutamate release was increased in synaptosomes from the cortex and hippocampus, while GABA release was decreased in synaptosomes from the cortex, but not in the hippocampus [48]. The slowed burst frequency that we observed does not match the hyperexcitability that these studies would predict. Our data indicate that the duration of Tat exposure is a key factor in determining any resulting change in network activity so timing could be a confounding factor. Changes in neurotransmitter release likely occur in the context of Tat-induced changes in the function of ion channels that regulate network excitability. For example, enhanced Ca2+ influx due to Tat-induced NMDAR potentiation could produce a Ca2+-activated hyperpolarization, which occurs following repetitive firing in hippocampal neurons [49], thereby reducing the frequency of action potential bursts and spontaneous Ca2+ spikes.

In addition to Tat altering network excitability via a neuronal mechanism, Tat could act via glial mechanisms. [Ca2+]i transients in astrocytes evoke the release of glutamate, which increases neuronal excitability via activation of GluN2B-containing NMDARs [50]. Furthermore, Ca2+-dependent glutamate release from astrocytes can activate presynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) to potentiate synaptic neurotransmitter release [51]. Indeed, Tat is taken up by astrocytes [52] thereby leading to transient increases in [Ca2+]i [53, 54] and impaired uptake of extracellular glutamate [55]. Microglia can also affect neuronal excitability via the release of inflammatory mediators [56]. Tat evokes the release of the proinflammatory cytokines tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-1 beta, and interleukin-6 from human microglia [57]. In sum, diverse mechanisms from multiple cell types can contribute to Tat-induced network dysfunction.

Neuroplasticity allows neurons and the networks in which they reside to adapt to changing environments. Our data indicate that Tat-induced changes in network function adapt in the maintained presence of Tat. We speculate that the adaptive response is a mechanism to compensate for a neurotoxic environment. If we extrapolate these results to a patient with HAND, the changes in synaptic and network function may improve neuronal survival at the expense of cognitive function. Thus, pharmacologically improving network function without reducing neuronal survival will require detailed knowledge of the signaling involved in both synaptic plasticity and cell death pathways [58]. Furthermore, because the network adapts in the presence of neurotoxin, a time course of HIV neurotoxicity will be required for a thorough understanding of HIV-associated neuropathogenesis and precise timing of potential therapeutic intervention.

The mechanism of adaptation remains unknown, although several potential explanations exist. Tat potentiates NMDAR function [12, 13], which then gradually returns to control levels during prolonged exposure [36]. Interestingly, adaptation of both Tat-induced potentiation of NMDAR function and Tat-induced changes in network activity were pronounced following 24 h exposure to Tat. Perhaps enhanced Ca2+ influx due to Tat-induced NMDAR potentiation contributes to elevated Ca2+ spike amplitude and reduced Ca2+ spike frequency then, as NMDAR function gradually returns to normal, network function recovers. NMDAR adaptation results from potentiation of NMDARs leading to Ca2+-induced nitric oxide production with subsequent activation of a kinase cascade to ultimately remodel the actin cytoskeleton [36]. Alternatively, a mechanism similar to homeostatic scaling could explain the adaptation of Tat-induced network changes. Homeostatic scaling is a mechanism to adjust the excitability of networked neurons [59]. Indeed, treatment with Tat for 24 h causes a reduction in the ratio of excitatory-to-inhibitory synapses [15, 16], perhaps as a mechanism to compensate for over excitation of the network. Thus, it is possible that the adaptation of network activity is the result of reduced excitatory tone and elevated inhibitory tone.

Infection with HIV is associated with the development of new-onset seizures [60, 61], however the cause of seizure disorders in a large percentage of HIV-infected patients remains unknown [62]. The HIV-1 Tat protein may contribute to the production of seizures because it increases neuronal excitability in vitro [24, 26, 27] and in vivo [48]. Indeed, transgenic animals expressing high levels of Tat exhibited seizures and cognitive abnormalities, although these animals were quite sick, thereby complicating determination of Tat’s role in the seizures [63]. EEG rhythms in HIV infected patients are abnormal; they appear to reflect the neurotoxic effects of HIV and have been proposed as potential biomarkers to monitor antiretroviral treatment in the brain [4]. Presently, we cannot relate the changes in network function observed in vitro to EEG changes in HIV patients. However, the in vitro work does establish the principle that networks adapt to the presence HIV neurotoxins and suggest that viewing EEG changes as an adaptive response might facilitate interpretation and therapeutic intervention.

In summary, we show that 4 h exposure to Tat decreased the frequency of spontaneous action potential bursts and Ca2+ spikes as well as increased the duration of action potential bursts and amplitude of Ca2+ spikes. Tat-induced changes in Ca2+ spiking were dependent on LRP and adapted following 24 h exposure. These findings show that Tat altered network function, which may contribute to the neurotoxicity observed in patients infected with HIV. Future studies will investigate the cellular mechanisms that alter network function, determine the pharmacology for reversing adaptation, and extend this study to in vivo models.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Jon Raybuck for his help in producing the supplemental video and Rebecca Maki for her efforts in confirming Tat’s effect on network activity using photometry. This work was supported by NIH grant DA07304 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to SAT. National Institute on Drug Abuse Training Grants supported KK (DA007097) and MG (DA07234).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Heaton RK, Franklin DR, Ellis RJ, McCutchan JA, Letendre SL, Leblanc S, et al. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders before and during the era of combination antiretroviral therapy: differences in rates, nature, and predictors. J Neurovirol. 2011;17:3–16. doi: 10.1007/s13365-010-0006-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antinori A, Arendt G, Becker JT, Brew BJ, Byrd DA, Cherner M, et al. Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology. 2007;69(18):1789–99. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000287431.88658.8b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellis R, Langford D, Masliah E. HIV and antiretroviral therapy in the brain: neuronal injury and repair. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8(1):33–44. doi: 10.1038/nrn2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babiloni C, Buffo P, Vecchio F, Onorati P, Muratori C, Ferracuti S, et al. Cortical sources of resting-state EEG rhythms in “experienced” HIV subjects under antiretroviral therapy. Clin Neurophysiol. 2014;125(9):1792–802. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2014.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Modi M, Mochan A, Modi G. New onset seizures in HIV--seizure semiology, CD4 counts, and viral loads. Epilepsia. 2009;50(5):1266–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaul M, Lipton SA. Mechanisms of neuroimmunity and neurodegeneration associated with HIV-1 infection and AIDS. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2006;1(2):138–51. doi: 10.1007/s11481-006-9011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li W, Li G, Steiner J, Nath A. Role of Tat Protein in HIV Neuropathogenesis. Neurotox Res. 2009;16(3):205–20. doi: 10.1007/s12640-009-9047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson TP, Patel K, Johnson KR, Maric D, Calabresi PA, Hasbun R, et al. Induction of IL-17 and nonclassical T-cell activation by HIV-Tat protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(33):13588–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308673110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bachani M, Sacktor N, McArthur JC, Nath A, Rumbaugh J. Detection of anti-tat antibodies in CSF of individuals with HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. J Neurovirol. 2013;19(1):82–8. doi: 10.1007/s13365-012-0144-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fitting S, Ignatowska-Jankowska BM, Bull C, Skoff RP, Lichtman AH, Wise LE, et al. Synaptic dysfunction in the hippocampus accompanies learning and memory deficits in human immunodeficiency virus type-1 tat transgenic mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;73(5):443–53. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carey AN, Sypek EI, Singh HD, Kaufman MJ, McLaughlin JP. Expression of HIV-Tat protein is associated with learning and memory deficits in the mouse. Behav Brain Res. 2012;229(1):48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krogh KA, Wydeven N, Wickman K, Thayer SA. HIV-1 protein Tat produces biphasic changes in NMDA-evoked increases in intracellular Ca concentration via activation of Src kinase and nitric oxide signaling pathways. J Neurochem. 2014;130:642–56. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haughey NJ, Nath A, Mattson MP, Slevin JT, Geiger JD. HIV-1 Tat through phosphorylation of NMDA receptors potentiates glutamate excitotoxicity. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2001;78(3):457–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00396.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Longordo F, Feligioni M, Chiaramonte G, Sbaffi PF, Raiteri M, Pittaluga A. The human immunodeficiency virus-1 protein transactivator of transcription up-regulates N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor function by acting at metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 receptors coexisting on human and rat brain noradrenergic neurones. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317(3):1097–105. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.099630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim HJ, Martemyanov KA, Thayer SA. Human immunodeficiency virus protein Tat induces synapse loss via a reversible process that is distinct from cell death. J Neurosci. 2008;28(48):12604–13. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2958-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hargus NJ, Thayer SA. Human Immunodeficiency Virus-1 Tat Protein Increases the Number of Inhibitory Synapses between Hippocampal Neurons in Culture. J Neurosci. 2013;33(45):17908–20. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1312-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eugenin EA, King JE, Nath A, Calderon TM, Zukin RS, Bennett MV, et al. HIV-tat induces formation of an LRP-PSD-95- NMDAR-nNOS complex that promotes apoptosis in neurons and astrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(9):3438–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611699104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turrigiano G. Homeostatic synaptic plasticity: local and global mechanisms for stabilizing neuronal function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4(1):a005736. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waataja JJ, Kim HJ, Roloff AM, Thayer SA. Excitotoxic loss of post-synaptic sites is distinct temporally and mechanistically from neuronal death. J Neurochem. 2008;104(2):364–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04973.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim HJ, Shin AH, Thayer SA. Activation of Cannabinoid Type 2 Receptors Inhibits HIV-1 Envelope Glycoprotein gp120-Induced Synapse Loss. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;80(3):357–66. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.071647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen M, Piser TM, Seybold VS, Thayer SA. Cannabinoid receptor agonists inhibit glutamatergic synaptic transmission in rat hippocampal cultures. Journal of Neuroscience. 1996;16(14):4322–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-14-04322.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Y, Popko J, Krogh KA, Thayer SA. Epileptiform stimulus increases Homer 1a expression to modulate synapse number and activity in hippocampal cultures. J Neurophysiol. 2013;130:1494–504. doi: 10.1152/jn.00580.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1985;260(6):3440–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nath A, Psooy K, Martin C, Knudsen B, Magnuson DS, Haughey N, et al. Identification of a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat epitope that is neuroexcitatory and neurotoxic. J Virol. 1996;70(3):1475–80. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1475-1480.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng J, Nath A, Knudsen B, Hochman S, Geiger JD, Ma M, et al. Neuronal excitatory properties of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein. Neuroscience. 1998;82(1):97–106. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00174-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brailoiu GC, Brailoiu E, Chang JK, Dun NJ. Excitatory effects of human immunodeficiency virus 1 Tat on cultured rat cerebral cortical neurons. Neuroscience. 2008;151(3):701–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chi X, Amet T, Byrd D, Chang KH, Shah K, Hu N, et al. Direct effects of HIV-1 Tat on excitability and survival of primary dorsal root ganglion neurons: possible contribution to HIV-1-associated pain. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiao H, Neuveut C, Lee H, Benkirane M, Rich EA, Murphy PM, et al. Selective CXCR4 antagonism by Tat: implications for in vivo expansion of coreceptor use by HIV-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(21):11466–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.21.11466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siebler M, Koller H, Stichel CC, Muller HW, Freund HJ. Spontaneous activity and recurrent inhibition in cultured hippocampal networks. Synapse. 1993;14(3):206–13. doi: 10.1002/syn.890140304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fletcher TL, Cameron P, De Camilli P, Banker G. The distribution of synapsin I and synaptophysin in hippocampal neurons developing in culture. The Journal of Neuroscience. 1991;11(6):1617–26. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-06-01617.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rao A, Kim E, Sheng M, Craig AM. Heterogeneity in the Molecular Composition of Excitatory Postsynaptic Sites During Development of Hippocampal Neurons in Culture. Journal of Neuroscience. 1998;18(4):1217–29. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-04-01217.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaech S, Banker G. Culturing hippocampal neurons. Nature protocols. 2006;1(5):2406–15. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLeod JR, Jr, Shen M, Kim DJ, Thayer SA. Neurotoxicity mediated by aberrant patterns of synaptic activity between rat hippocampal neurons in culture. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1998;80(5):2688–98. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.5.2688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Y, Jones M, Hingtgen CM, Bu G, Laribee N, Tanzi RE, et al. Uptake of HIV-1 tat protein mediated by low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein disrupts the neuronal metabolic balance of the receptor ligands. Nat Med. 2000;6(12):1380–7. doi: 10.1038/82199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bu G. The roles of receptor-associated protein (RAP) as a molecular chaperone for members of the LDL receptor family. Int Rev Cytol. 2001;209:79–116. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(01)09011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krogh KA, Lyddon E, Thayer SA. HIV-1 Tat activates a RhoA signaling pathway to reduce NMDA-evoked calcium responses in hippocampal neurons via an actin-dependent mechanism. J Neurochem. 2015;132:354–66. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gemignani A, Paudice P, Pittaluga A, Raiteri M. The HIV-1 coat protein gp120 and some of its fragments potently activate native cerebral NMDA receptors mediating neuropeptide release. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;12(8):2839–46. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lipton AS, Sucher JN, Kaiser KP, Dreyer BE. Synergistic effects of HIV coat protein and NMDA receptor-mediated neurotoxicity. Neuron. 1991;7:1–28. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90079-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toggas SM, Masliah E, Mucke L. Prevention of hiv-1 gp120-induced neuronal damage in the central nervous system of transgenic mice by the nmda receptor antagonist memantine. Brain research. 1996;706(2):303–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01197-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mishra A, Kim HJ, Shin AH, Thayer SA. Synapse Loss Induced by Interleukin-1β Requires Pre- and Post-synaptic Mechanisms. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11481-012-9342-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Viviani B, Bartesaghi S, Gardoni F, Vezzani A, Behrens MM, Bartfai T, et al. Interleukin-1b Enhances NMDA Receptor-Mediated Intracellular Calcium Increase through Activation of the Src Family of Kinases. J Neurosci. 2003;23(25):8692–700. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-25-08692.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang J, Hu D, Xia J, Liu J, Zhang G, Gendelman HE, et al. Enhancement of NMDA Receptor-Mediated Excitatory Postsynaptic Currents by gp120-Treated Macrophages: Implications for HIV-1-Associated Neuropathology. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11481-013-9468-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song L, Nath A, Geiger JD, Moore A, Hochman S. Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 Tat Protein Directly Activates Neuronal N -methyl- D -aspartate Receptors at an Allosteric Zinc-Sensitive Site. Journal of Neurovirology. 2003;9(3):399– 403. doi: 10.1080/13550280390201704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lillis AP, Van Duyn LB, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Strickland DK. LDL receptor-related protein 1: unique tissue-specific functions revealed by selective gene knockout studies. Physiol Rev. 2008;88(3):887–918. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00033.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ashwood TJ, Wheal HV. The expression of N-methyl-D-aspartate-receptor-mediated component during epileptiform synaptic activity in hippocampus. Br J Pharmacol. 1987;91(4):815–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1987.tb11280.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rose K, Christine C, Choi D. Magnesium removal induces paroxysmal neuronal firing and NMDA receptor-mediated neuronal degeneration in cortical cultures. Neurosci Lett. 1990;115:313–7. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(90)90474-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Musante V, Summa M, Neri E, Puliti A, Godowicz TT, Severi P, et al. The HIV-1 Viral Protein Tat Increases Glutamate and Decreases GABA exocytosis from Human and Mouse Neocortical Nerve Endings. Cerebral Cortex. 2010;20(1):1974–84. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zucchini S, Pittaluga A, Brocca-Cofano E, Summa M, Fabris M, De Michele R, et al. Increased excitability in tat-transgenic mice: role of tat in HIV-related neurological disorders. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;55:110–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hotson JR, Prince DA. A calcium-activated hyperpolarization follows repetitive firing in hippocampal neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1980;43(2):409–19. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.43.2.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fellin T, Pascual O, Gobbo S, Pozzan T, Haydon PG, Carmignoto G. Neuronal Synchrony Mediated by Astrocytic Glutamate through Activation of Extrasynaptic NMDA Receptors. Neuron. 2004;43(3):729–43. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Perea G, Araque A. Astrocytes Potentiate Transmitter Release at Single Hippocampal Synapses. Science. 2007;317(5841):1083–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1144640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ma M, Nath A. Molecular determinants for cellular uptake of Tat protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in brain cells. J Virol. 1997;71(3):2495–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2495-2499.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tewari M, Monika Varghese RK, Menon M, Seth P. Astrocytes mediate HIV-1 Tat-induced neuronal damage via ligand-gated ion channel P2X7R. J Neurochem. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jnc.12953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.El-Hage N, Gurwell JA, Singh IN, Knapp PE, Nath A, Hauser KF. Synergistic increases in intracellular Ca2+, and the release of MCP-1, RANTES, and IL-6 by astrocytes treated with opiates and HIV-1 Tat. Glia. 2005;50(2):91–106. doi: 10.1002/glia.20148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou BY, Liu Y, Kim B, Xiao Y, He JJ. Astrocyte activation and dysfunction and neuron death by HIV-1 Tat expression in astrocytes. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;27(3):296–305. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bernardino L, Xapelli S, Silva AP, Jakobsen B, Poulsen FR, Oliveira CR, et al. Modulator Effects of Interleukin-1{beta} and Tumor Necrosis Factor-{alpha} on AMPA-Induced Excitotoxicity in Mouse Organotypic Hippocampal Slice Cultures. J Neurosci. 2005;25(29):6734–44. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1510-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sheng WS, Hu S, Hegg CC, Thayer SA, Peterson PK. Activation of human microglial cells by HIV-1 gp41 and Tat proteins. Clin Immunol. 2000;96(3):243–51. doi: 10.1006/clim.2000.4905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shin AH, Kim HJ, Thayer SA. Subtype selective NMDA receptor antagonists induce recovery of synapses lost following exposure to HIV-1 Tat. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166(3):1002–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01805.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marder E, Goaillard JM. Variability, compensation and homeostasis in neuron and network function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(7):563–74. doi: 10.1038/nrn1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holtzman DM, Kaku DA, So YT. New-onset seizures associated with human immunodeficiency virus infection: causation and clinical features in 100 cases. Am J Med. 1989;87(2):173–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(89)80693-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kellinghaus C, Engbring C, Kovac S, Moddel G, Boesebeck F, Fischera M, et al. Frequency of seizures and epilepsy in neurological HIV-infected patients. Seizure. 2008;17(1):27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2007.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pesola GR, Westfal RE. New-onset generalized seizures in patients with AIDS presenting to an emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1998;5(9):905–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1998.tb02820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim BO, Liu Y, Ruan Y, Xu ZC, Schantz L, He JJ. Neuropathologies in transgenic mice expressing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Tat protein under the regulation of the astrocyte-specific glial fibrillary acidic protein promoter and doxycycline. Am J Pathol. 2003;162(5):1693–707. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64304-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.