Abstract

Sepsis, a leading cause of mortality in intensive care units worldwide, is often a result of overactive and systemic inflammation following serious infections. We found that mice lacking immediate early responsive gene X-1 (IEX-1) were prone to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) -induced endotoxemia. A nonlethal dose of LPS provoked numerous aberrations in IEX-1 knockout (KO) mice including pancytopenia, increased serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and lung neutrophilia, concurrent with liver and kidney damage, followed by death. Given these results, in conjunction with a proven role for IEX-1 in the regulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis during stress, we pre-treated IEX-1 KO mice with Mitoquinone (MitoQ), a mitochondrion-based antioxidant prior to LPS injection. The treatment significantly reduced ROS formation in circulatory cells and protected against pancytopenia and multiple organ failure, drastically increasing the survival rate of IEX-1 KO mice challenged by this low dose of LPS. This study confirms significant contribution of mitochondrial ROS to the etiology of sepsis.

Keywords: IEX-1, reactive oxygen species, mitoquinone, sepsis

1. Introduction

Sepsis affects over 18 million people worldwide each year and is caused by systemic inflammation owing to severe infections (1). The symptoms are initially associated with aberrations of white blood cell counts, edema, and fever or hypothermia, which, if unchecked, could be deteriorating and lead to multiple organ failure often followed by death. Cytokine storms provoked by infiltrating immune cells in major organs, in combination with activation of complement pathways, can activate the procoagulation factors in the endothelium and damage microvasculature following intravascular clotting and microvascular thrombosis (2). During this process, several sources of ROS have been identified including those produced by respiratory bursts in activated phagocytes and neutrophils, and by the mitochondrial respiratory chain (3–8). Growing evidence suggests that excess production of ROS by tissue-infiltrating immune cells is critical in the etiology of sepsis.

IEX-1 is essential in the regulation of inflammation and ROS homeostasis during states of stress. It is up regulated in response to various stressors such as irradiation, viral infections, and growth factors. Its expression protects stressed cells from apoptosis, which lies within its involvement in the regulation of mitochondrial respiratory chain activity and the ability to control mitochondrial membrane potential through targeting F1F0-ATPase inhibitor (IF1) for degradation (9;10). IEX-1-mediated modulation of IF1 degradation was shown to increase F1F0 ATPase activity and prevent a rise of ROS induced by various apoptotic stimuli at mitochondria. Consistent with this, a loss of IEX-1 during non-myeloablative irradiation results in an myelodysplastic-like syndrome, accompanied by increases of ROS in multiple types of circulating blood cells that adversely affect the function, morphology, and survival of these cells (11;12). As well, absence of IEX-1 has been linked to inflammatory states in several autoimmune disease models due to the inability to quell immune responses in the loss of function (9;13;14). Given these findings and the strong induction of IEX-1 by LPS we believe that IEX-1 plays a favorable role in preventing the excess ROS production often found accompanying septic shock.

In the present investigation, we show increased susceptibility of IEX-1 deficient mice to LPS-induced endotoxemia as compared to wild type control mice. Pre-treatment of the mice with MitoQ, a mitochondrion-based antioxidant, not only decreased ROS levels in granulocytes, red blood cells and platelets, cell types particularly affected by sepsis, but also reversed the septic etiologies. These findings provide novel insights into the role of IEX-1 in maintenance of ROS homeostasis during septicemia and again suggest that MitoQ may be useful for preventing sepsis in patients with known mitochondrial dysfunction.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Mice

Wild type (WT) control mice and IEX-1 KO mice on mixed 129Sv/C57BL/6 background (F1) were generated by gene-targeting deletion in our laboratory as previously described (15). For sepsis induction, mice at 8 weeks of age, were administered a single intra peritoneal (i.p.) dose of LPS (20mg/kg) (E.coli 0111:B4) (Sigma). Mitoquinone was administered to mice in drinking water containing 250μM MitoQ ad libitum for 2 weeks pre-LPS challenge, with a change of the drinking water every three days. Animals were maintained in pathogen-free animal facilities of Massachusetts General Hospital in compliance with institutional guidelines.

2.2 Flow cytometric analysis

Peripheral blood cells were stained with rat anti-mouse antibodies against mature blood cell markers obtained from BD Biosciences at concentrations per manufacturer’s instructions. For macrophage detection, cells were blocked with an Fc receptor block (BD Biosciences) and stained with PE-conjugated Mac-1(CD11b). Erythropoietic red blood cells were stained using Ter-119 (Ter-119) antibody, and platelets using CD41 (MWReg30) antibody (eBiosciences). Flow cytometric studies were performed on a FACSAria (BD Bioscience) and data were analyzed by FlowJo software (Tree Star).

2.3 Blood parameters and histology

Blood smears and complete blood cell counts (CBC) were evaluated for pathologies. For CBC, blood was collected via tail vein into EDTA-coated microtainer tubes (BD Bioscience) and analyzed on a HemaTrue veterinary hematology analyzer (Heska Corporation). Serum AST was measured using a DRI-CHEM analyzer (Heska). Peripheral blood smears were stained with Wright-Giemsa (Sigma-Aldrich). Formalin fixed tissues from lung, spleen and kidney were embedded, cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for histological analysis. Microscopic analysis was conducted with a Zeiss Axiophot and images were captured using Picture Frame 2.3 software.

2.4 ROS and JC-1 Analysis

ROS were measured by incubation of cells in serum-free RPMI media or phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with 5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate, acetyl ester (CM-H2DCFDA or DCF) 5μM (Sigma) for 30 minutes and measured by shifts in green mean fluorescence intensity (MFI). Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was measured by incubation of the cells for 20 minutes with 5μM JC-1 (Invitrogen) in PBS as per manufacturer’s instructions, followed by flow cytometric analysis. MMP alteration was expressed as a ratio of red to green fluorescence due to JC-1 aggregate in mitochondria.

2.5 Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD). Differences in mean values among multiple groups or between two groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA analysis with Tukey post-test or two-tailed Student’s t-test, respectively using Graphpad Prism 5 (Graphpad Software). Animal survival was analyzed with Kaplan-Meyer tests. Statistical significance or high significance was considered at P< 0.05 or P< 0.01, respectively.

3. Results

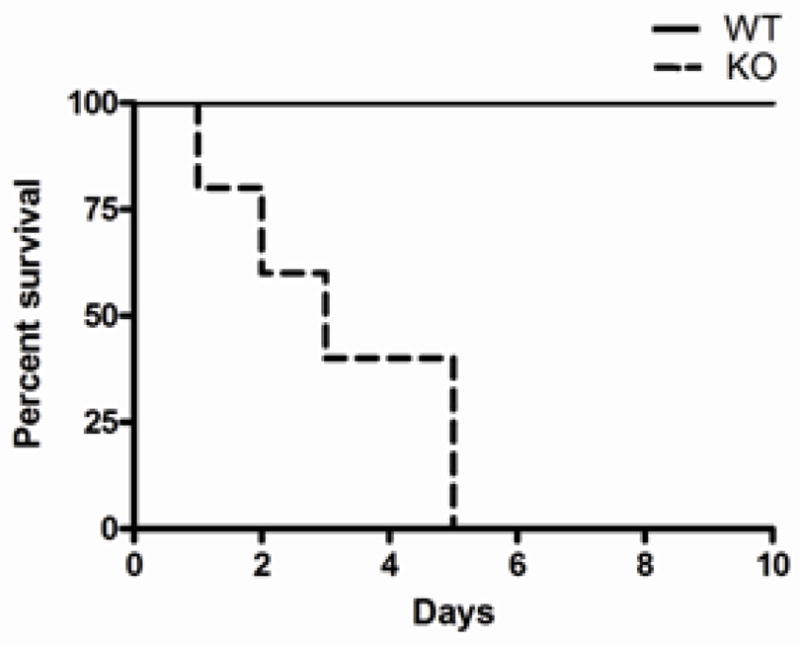

3.1 IEX-1 deficient mice are prone to LPS-induced septicemia

In light of the importance of IEX-1 in the regulation of ROS homeostasis within mitochondria, we tested whether null mutation of IEX-1 predisposed to sepsis induced by LPS. To this end, WT and IEX-1 KO mice were i.p administered with LPS at a nonlethal dose of 20mg/kg, followed by monitoring survival of the mice. No KO mice survived past 5 days of treatment, as opposed to WT control mice that all survived (KO 0/8 vs. WT 8/8) (Figure 1). The result confirms increased susceptibility to LPS–induced sepsis in the absence of IEX-1.

Figure 1.

IEX-1 deficient mice are prone to LPS-induced endotoxemia. Kaplan-Meyer analysis of the survival of WT and KO mice subjected to a nonlethal dose of LPS is shown. Data shown are from two experiments with n= 8 in each treatment group.

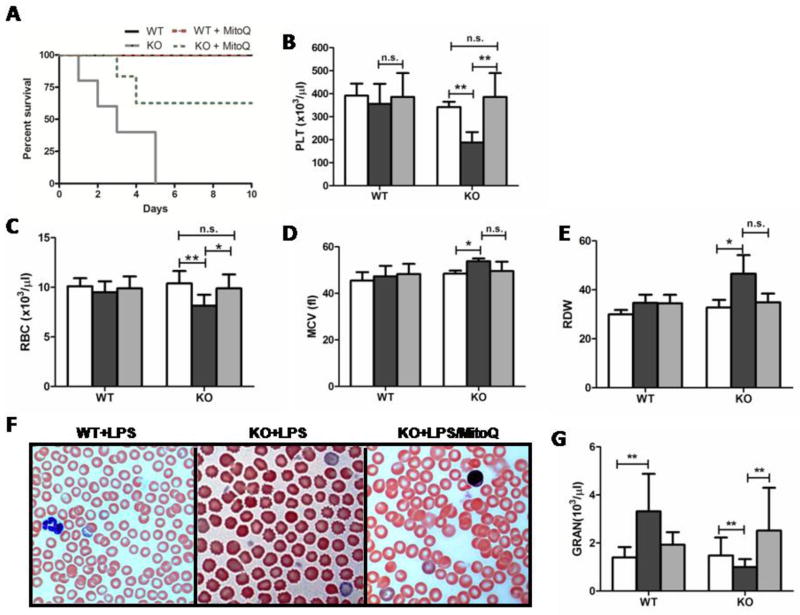

3.2 MitoQ reduces endotoxemic mortality and maintains hemostatic blood cell counts in the loss of IEX-1

A number of investigations, including ours, have shown that MitoQ can ameliorate ROS-induced damage during stress (12;16;17). To test its effects in the context of septicemia, we treated the mice with MitoQ for two weeks prior to LPS challenge, by adding the anti-oxidant into drinking water as previously described (12). The treatment robustly reduced the mortality rate to 25%, from 100%: six out of eight mice survived from LPS-induced septic shock (Fig. 2A). Alongside these results, MitoQ prevented thrombocytopenia induced by LPS in KO mice (Fig. 2B), without incurring any adverse effects on platelet (PLT) mean volume or morphology (data not shown). Because anemia has been shown as an important piece of the etiology of septic shock, we investigated red blood cells and their morphological parameters during endotoxemia in the loss of IEX-1(18–20). Similar to platelets, red blood cells (RBC) were also decreased in number during endotoxemia (Fig. 2C), concomitant with an increased mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and red cell distribution width (RDW) (Fig. 2D and E). These morphological aberrations were well noted within peripheral blood smears of mice 24-hours post LPS challenge exhibiting pokilocytosis consisting of both spherocytes and echinocytes (Fig. 2F). In sharp contrary, WT RBCs maintained normal morphological parameters in 24 hours after a similar LPS challenge (Fig. 2F). LPS-induced abnormalities were almost completely corrected by MitoQ pre-treatment, corroborating protective effects of MitoQ on peripheral blood cells (Fig. 2B–F). There were no differences in peripheral blood cell parameters between untreated and MitoQ treated KO and WT control mice (data not shown), similar to previous investigations (21).

Figure 2.

MitoQ pre-treatment reverses endotoxemic effects of LPS in IEX-1 deficient mice. Kaplan-Meyer analysis is shown for the survival of WT and KO mice with MitoQ pre-treatment before LPS challenge as in Figure 1(A) with n= 8 in each WT and KO treatment group. Platelet (B) and red blood cell (C) levels were measured, alongside red blood cell mean corpuscular volume (D) and distribution width (E). Changes in red blood cell morphology were visible through blood representative smears (100x magnification) (F). Granulocyte levels were also noted (G). Data shown (B–E, G) are from two experiments with n= 5 in each treatment group. Groups are denoted as Control (white), LPS (black), and LPS+ MitoQ (grey). *P< 0.05 and **P< 0.01

Commonly, sepsis may induce peripheral expansion of granulocytes or mobilization of bone marrow granulocytes in an attempt to clean and neutralize infections. During endotoxemia, WT mice displayed such a noted expansion, whereas KO mice showed a significant decrease in circulating granulocytes 24 hours post-LPS challenge. However, when KO mice were pretreated with MitoQ, granulocyte counts were expanded in response to endotoxemia to a WT level (Fig. 2G). Taken together, these data show that loss of IEX-1 results in a predisposition to septic conditions such as pancytopenias, giving way to increased mortality, which can be prevented by MitoQ treatment.

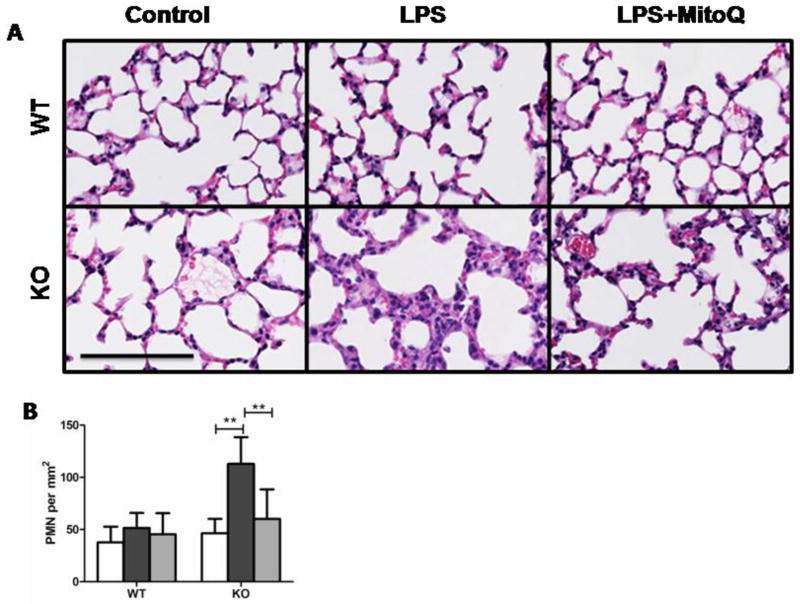

3.3 MitoQ attenuates LPS-induced lung damage and neutrophilia

A number of studies have shown the lungs as being a main target organ for damage in response to LPS challenge, leading us to examine the histology of lung tissue in mice 24 hours post-LPS challenge (22). KO mice receiving LPS exhibited severe inflammation and edema in the lung (Fig. 3A), in parallel to significant increases in the number of neutrophils as compared to WT mice treated similarly (Fig. 3 A and B). LPS-treated KO lungs exhibited an almost 3-fold increase in polymorphonuclear granulocytes (PMN) (112.9±25.6 versus KO control 46.5±13.7) (****************Fig. 3B). In contrast, no significant differences were noted in PMN populations in WT mice regardless of whether the mice are treated with or without LPS (Fig. 3). PMN lung infiltration was prevented by MitoQ treatment, leading to nearly normal levels of PMN counts within the lung. MitoQ-mediated attenuation of inflammation and PMN infiltration were clearly evidenced in lung histology (Fig. 3A, panel 3).

Figure 3.

LPS induced lung neutrophilia and tissue damage are exacerbated in the loss of IEX-1. Representative H&E stainings of lung tissues were prepared from WT and KO control mice, or with LPS and MitoQ+LPS treatments (A). Bar (100μm). PMN were counted in the lung tissue of subject mice (B). Groups are denoted as Control (white), LPS (black), and LPS+ MitoQ (grey). Data shown are from two experiments where n= 5. **P< 0.01

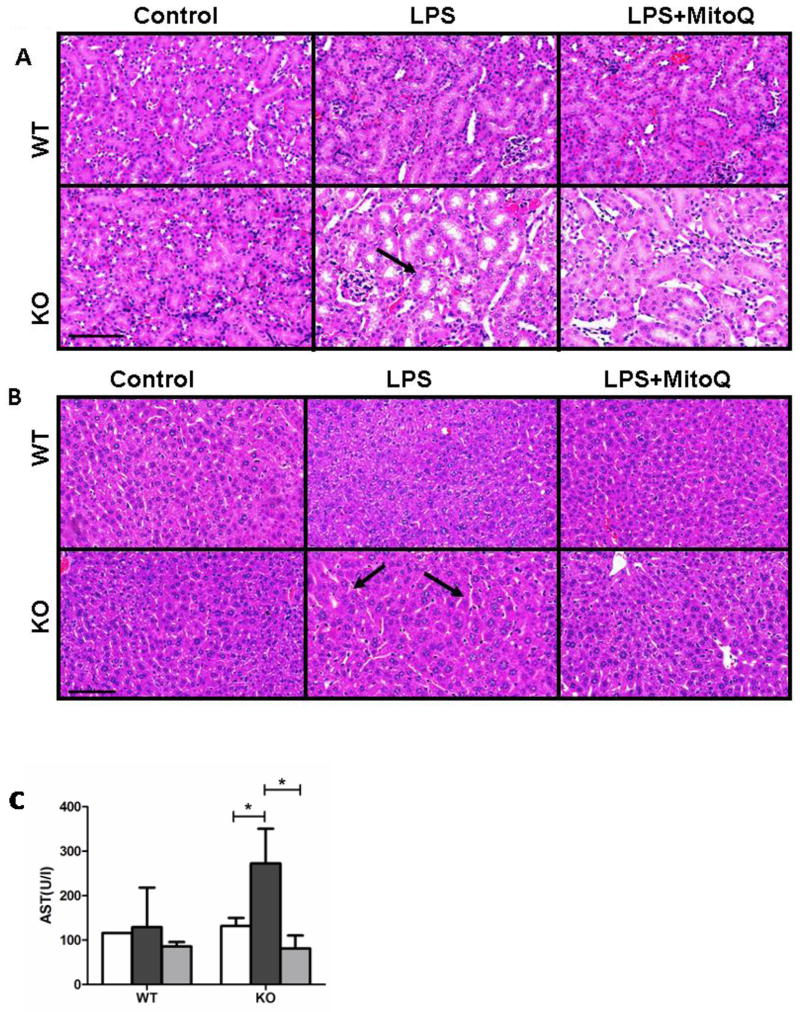

3.4 MitoQ prevents LPS-induced damage of the kidney and liver

Effects of LPS alone or with MitoQ treatment were then examined in kidney and liver tissues, two other prominent target organs in endotoxemia. The kidneys of LPS-treated KO mice displayed tubule dilation (arrow, Figure 4A) and apoptotic/damaged brush cell structure, pathologies that were resolved by MitoQ pretreatment (Fig. 4A). Livers of LPS-treated KO mice also showed hepatocellular apoptosis with pyknotic nuclei and an increased dilation of sinusoids (arrows) (Fig. 4B). These prominent pathological markers were noted in neither WT nor KO control mice nor KO mice with MitoQ treatment (Fig. 4B). To corroborate a decline in liver function in septic KO mice, we measured serum aspartate transaminase (AST), a common clinical marker for septicemia. As shown in Fig. 4C, KO septic mice showed significantly increased levels of AST, which were completely normalized by MitoQ pretreatment. These data provide evidence linking mitochondrial dysfunction to increased organ damage during septic states.

Figure 4.

MitoQ protects from LPS induced kidney and liver damage. Kidneys (A) and livers (B) of control and treated WT and KO mice were harvested 24 hours after LPS injection. Serum AST was measured in all subjects; Control (white), LPS (black), and LPS+ MitoQ (grey)(C). H&E stains are representative of two experiments with n= 5. Bar (100μm). Serum AST is a result of two experiments with n=3. *P< 0.05

3.5 MitoQ lowers ROS production in blood cells and preserves mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) during endotoxemia

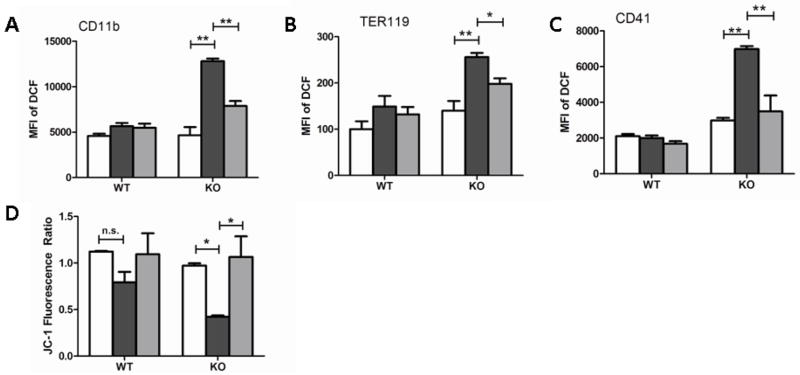

Given the pancytopenia development during endotoxemia in KO mice (Fig. 2), although it returned to normal levels with MitoQ treatment, we next determined if these cells were particularly sensitive to LPS-induced ROS formation. Flow cytometric analysis of blood samples taken 24 hours after LPS challenge showed increased ROS production in granulocytes (Fig. 5A), red blood cells (Fig. 5B), and platelets (Fig. 5C) during septicemia in KO mice. A direct role of MitoQ in preservation of mitochondrial function was investigated by measuring MMP in peripheral platelets of these mice using JC-1, a mitochondrial specific dye. In healthy cells, a potential-dependent accumulation of JC-1 dye within the mitochondria was evidenced by a shift from green to red fluorescence of JC-1 due to its red-flourescein J-aggregates. However, when MMP was disturbed, JC-1 failed to cross the electrophilic mitochondrial membrane, and no accumulation or aggregates of JC-1 but only green fluorescence of JC-1 monomers was detected. We observed decreased MMP in IEX-1 KO platelets in a standing state (Figure 5D). Further decreases in MMP were induced by LPS in WT mice, with more prominent effects on KO mice (Figure 5D). These levels of MMP alteration were specifically blunted by MitoQ. The results directly support the role of IEX-1 in the maintenance of platelet mitochondrial function under a threat of endotoxemia. It has been shown that decreases in platelet MMP correlate strongly with progression of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) in patients (23)(24), implicating a clinical significance of sepsis exacerbated by lack of IEX-1.

Figure 5.

Analysis of ROS and MMP in circulating blood cells. Cellular levels of ROS were analyzed in granulocyte (A), red blood cell (B) and platelet (C) populations from 2 experiments where n=5. JC-1 aggregation ratios are expressed as a ratio of red to green fluorescence of JC-1 in platelets collected from mice at a standing state, or MitoQ treated and nontreated groups 24 hours post-endotoxemic challenge (D). Data shown is from 2 experiments with similar results and n= 3 in each. Groups are denoted as Control (white), LPS (black), and LPS+ MitoQ (grey). *P< 0.05 and **P< 0.01

4. Discussion

We report here that a loss of IEX-1 impairs mitochondrial function and serves as a predisposing factor to sepsis. Mice lacking IEX-1 displayed a significantly increased mortality to endotoxin induced by a nonlethal dose of LPS, after peripheral multilineage cytopenias, infiltrating neutrophilia, and multiple organ damage. Previously, we have shown that a loss of IEX-1 results in unfettered ROS production during stress responses, which promotes us to use MitoQ to quell septic etiologies and reduce endotoxemic mortality. Due to the standing higher production of ROS in the loss of IEX-1, we chose MitoQ as a pretreatment. Apparently, MitoQ is able to sustain normality of RBCs and platelets both in their numbers and morphology. Neutrophil levels were also well maintained through the use of MitoQ, even allowing for expansion, similar to the response noted in WT mice. Loss of circulating IEX-1 deficient neutrophils in the absence of MitoQ, appear to be a result of tissue redistribution, as shown through increased lung neutrophilia. Furthermore, the ability of MitoQ to preserve steady circulating neutrophil numbers may also favor clearance of LPS or pathogens in the setting of infections, eliminating the sources that provoke cytokine storms and complement cascades so that micovascular occlusions and organ dysfunction are sufficiently prevented This anti-inflammatory effect of MitoQ preserved both histology and function of the liver, kidney, and lung, all of which are crucial for the survival of LPS challenge.. Our investigations argue that MitoQ can serve as a protective agent during sepsis in distinct groups of patients who have preexisting mitochondrial dysfunction such as elderly populations.

Unfortunately, a use of antioxidants as a beneficial supplement during sepsis has shown few or no benefits in critically ill patients (25–27). One of the reasons for this may be that anti-oxidant is used too late as organ damage may have been caused in these critically ill patients. Our data suggest that if anti-oxidant is given early, such as immediately after severe infection or before neutropenic development, it may be able to prevent organ damage. Another reason may be the failure of most antioxidants to accumulate within the mitochondria where a high level of ROS is produced. In contrast, MitoQ is designed to target the mitochondria, due to its conjugation to lipophilic ions, whose accumulation within the mitochondria is driven solely by the mitochondrial membrane potential (28). Once within the mitochondria, MitoQ is absorbed within the inner membrane of the matrix surface of mitochondria, where it is recycled into an ubiquinol antioxidant via the respiratory chain. Targeting this antioxidant into the matrix has allowed for MitoQ to protect against oxidative injury in multiple disease models, particularly septicemia (1;16;17). For example, recent in vitro studies showed that human epithelial cells treated with MitoQ exhibited a decrease in ROS formation and maintained mitochondrial membrane potential under septic conditions (29). In vivo, multiple rodent models show MitoQ’s protection of cardiac, liver and renal function under septicemic conditions (16;30). We have shown that MitoQ is able to maintain MMP in the loss of IEX-1 during an endotoxemic challenge, a finding that correlates strongly with a previous report of decreased platelet MMP in SIRS (23). Platelet function is essential to prevent internal bleeding in septic animals. It may be also critical in reducing systemic inflammatory responses because instability of mitochondrial membranes of platelets may lead to the release of “damage”-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) such as mitochondrial DNA and formyl peptides into circulation system, intensifying the inflammation in the subjects (24). Together, such findings may help underline the balance between corrective and exaggerated immune responses in the face of sepsis, allowing for more efficient treatment.

Sepsis treatment is mainly supportive currently, so any novel therapy with the propensity to protect against organ damage would be paramount in reducing septic mortality. Numerous studies consistently reporting mitochondrial dysfunction as a result of oxidative stress culminating in organ failure in septic patients, beg for further research on the preventive role of MitoQ against septicemia in patients with inadequate mitochondrial functions, in particular, in the elderly who show significantly higher mortality than young patients after serious infections.

Highlights.

Loss of IEX-1 predisposes to LPS-induced endotoxemia

MitoQ maintains red blood cell, platelet and granulocyte numbers during endotoxemia

MitoQ sustains mitochondrial membrane potential in platelets during endotoxemia

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael P. Murphy for the generous gift of MitoQ used in this study.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest Statement

The authors report no declarations of interest. This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants CA158756, AI089779, and DA028378 to M.X.W. H.R. designed and performed the research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. M.X.W. has designed and supervised research and wrote the manuscript. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Galley HF. Bench-to-bedside review: Targeting antioxidants to mitochondria in sepsis. Crit Care. 2010;14(4):230. doi: 10.1186/cc9098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nimah M, Brilli RJ. Coagulation dysfunction in sepsis and multiple organ system failure. Crit Care Clin. 2003 Jul;19(3):441–58. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0704(03)00008-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martins PS, Kallas EG, Neto MC, Dalboni MA, Blecher S, Salomao R. Upregulation of reactive oxygen species generation and phagocytosis, and increased apoptosis in human neutrophils during severe sepsis and septic shock. Shock. 2003 Sep;20(3):208–12. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000079425.52617.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Combadiere C, El BJ, Pedruzzi E, Hakim J, Perianin A. Stimulation of the human neutrophil respiratory burst by formyl peptides is primed by a protein kinase inhibitor, staurosporine. Blood. 1993 Nov 1;82(9):2890–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurtado-Nedelec M, Makni-Maalej K, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, Dang PM, El-Benna J. Assessment of priming of the human neutrophil respiratory burst. Methods Mol Biol. 2014;1124:405–12. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-845-4_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marchi LF, Sesti-Costa R, Ignacchiti MD, Chedraoui-Silva S, Mantovani B. In vitro activation of mouse neutrophils by recombinant human interferon-gamma: increased phagocytosis and release of reactive oxygen species and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014 Feb;18(2):228–35. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brealey D, Brand M, Hargreaves I, Heales S, Land J, Smolenski R, et al. Association between mitochondrial dysfunction and severity and outcome of septic shock. Lancet. 2002 Jul 20;360(9328):219–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09459-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fossati G, Moulding DA, Spiller DG, Moots RJ, White MR, Edwards SW. The mitochondrial network of human neutrophils: role in chemotaxis, phagocytosis, respiratory burst activation, and commitment to apoptosis. J Immunol. 2003 Feb 15;170(4):1964–72. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arlt A, Schafer H. Role of the immediate early response 3 (IER3) gene in cellular stress response, inflammation and tumorigenesis. Eur J Cell Biol. 2011 Jun;90(6–7):545–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shen L, Zhi L, Hu W, Wu MX. IEX-1 targets mitochondrial F1Fo-ATPase inhibitor for degradation. Cell Death Differ. 2009 Apr;16(4):603–12. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramsey H, Zhang Q, Brown DE, Steensma DP, Lin CP, Wu MX. Stress-induced hematopoietic failure in the absence of immediate early response gene X-1 (IEX-1, IER3) Haematologica. 2014 Feb;99(2):282–91. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.092452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramsey H, Zhang Q, Wu MX. Mitoquinone restores platelet production in irradiation-induced thrombocytopenia. Platelets. 2014 Jul;15:1–8. doi: 10.3109/09537104.2014.935315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sommer SL, Berndt TJ, Frank E, Patel JB, Redfield MM, Dong X, et al. Elevated blood pressure and cardiac hypertrophy after ablation of the gly96/IEX-1 gene. J Appl Physiol. 2006 Feb;100(2):707–16. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00306.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sina C, Arlt A, Gavrilova O, Midtling E, Kruse ML, Muerkoster SS, et al. Ablation of gly96/immediate early gene-X1 (gly96/iex-1) aggravates DSS-induced colitis in mice: role for gly96/iex-1 in the regulation of NF-kappaB. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010 Feb;16(2):320–31. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamelin V, Letourneux C, Romeo PH, Porteu F, Gaudry M. Thrombopoietin regulates IEX-1 gene expression through ERK-induced AML1 phosphorylation. Blood. 2006 Apr 15;107(8):3106–13. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lowes DA, Thottakam BM, Webster NR, Murphy MP, Galley HF. The mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ protects against organ damage in a lipopolysaccharide-peptidoglycan model of sepsis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008 Dec 1;45(11):1559–65. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowes DA, Webster NR, Murphy MP, Galley HF. Antioxidants that protect mitochondria reduce interleukin-6 and oxidative stress, improve mitochondrial function, and reduce biochemical markers of organ dysfunction in a rat model of acute sepsis. Br J Anaesth. 2013 Mar;110(3):472–80. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piagnerelli M, Boudjeltia KZ, Vanhaeverbeek M, Vincent JL. Red blood cell rheology in sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2003 Jul;29(7):1052–61. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1783-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piagnerelli M, Boudjeltia KZ, Vanhaeverbeek M. Etiology of anemia in critically ill patients: role of red blood cell rheology. Eur J Intern Med. 2005 Nov;16(7):537. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Piagnerelli M, Boudjeltia KZ, Brohee D, Piro P, Carlier E, Vincent JL, et al. Alterations of red blood cell shape and sialic acid membrane content in septic patients. Crit Care Med. 2003 Aug;31(8):2156–62. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000079608.00875.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodriguez-Cuenca S, Cocheme HM, Logan A, Abakumova I, Prime TA, Rose C, et al. Consequences of long-term oral administration of the mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ to wild-type mice. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010 Jan 1;48(1):161–72. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guo RF, Ward PA. Role of oxidants in lung injury during sepsis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007 Nov;9(11):1991–2002. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamakawa K, Ogura H, Koh T, Ogawa Y, Matsumoto N, Kuwagata Y, et al. Platelet mitochondrial membrane potential correlates with severity in patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013 Feb;74(2):411–7. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31827a34cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Q, Raoof M, Chen Y, Sumi Y, Sursal T, Junger W, et al. Circulating mitochondrial DAMPs cause inflammatory responses to injury. Nature. 2010 Mar 4;464(7285):104–7. doi: 10.1038/nature08780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abiles J, de la Cruz AP, Castano J, Rodriguez-Elvira M, Aguayo E, Moreno-Torres R, et al. Oxidative stress is increased in critically ill patients according to antioxidant vitamins intake, independent of severity: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2006;10(5):R146. doi: 10.1186/cc5068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mishra V. Oxidative stress and role of antioxidant supplementation in critical illness. Clin Lab. 2007;53(3–4):199–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crimi E, Sica V, Slutsky AS, Zhang H, Williams-Ignarro S, Ignarro LJ, et al. Role of oxidative stress in experimental sepsis and multisystem organ dysfunction. Free Radic Res. 2006 Jul;40(7):665–72. doi: 10.1080/10715760600669612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.James AM, Sharpley MS, Manas AR, Frerman FE, Hirst J, Smith RA, et al. Interaction of the mitochondria-targeted antioxidant MitoQ with phospholipid bilayers and ubiquinone oxidoreductases. J Biol Chem. 2007 May 18;282(20):14708–18. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611463200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Apostolova N, Garcia-Bou R, Hernandez-Mijares A, Herance R, Rocha M, Victor VM. Mitochondrial antioxidants alleviate oxidative and nitrosative stress in a cellular model of sepsis. Pharm Res. 2011 Nov;28(11):2910–9. doi: 10.1007/s11095-011-0528-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Supinski GS, Murphy MP, Callahan LA. MitoQ administration prevents endotoxin-induced cardiac dysfunction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009 Oct;297(4):R1095–R1102. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90902.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]