Abstract

This article provides an overview of an interactive online training designed for healthcare professionals to hone their skills in assisting pregnant women to quit smoking and to remain quit postpartum. The curriculum teaches a best practice approach for smoking cessation, the 5A’s, and is based on current clinical recommendations. The program offers five interactive case simulations and comprehensive discussions of patient visits, short lectures on relevant topics from leading experts, interviews with real patients who have quit, and a dedicated website of pertinent links and office resources. The training is accredited for up to 4.5 hours of continuing education credits.

Introduction

Smoking during pregnancy remains one of the most common preventable causes of infant morbidity and mortality. Women who smoke during pregnancy experience increased risk of pregnancy complications, including placental previa, placental abruption, and premature rupture of the membranes (PROM). In addition, infants of mothers who smoked during pregnancy are more likely to be delivered early and have higher rates of restricted fetal growth, preterm-related death, and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).1 In 2002, 5%–8% of preterm deliveries, 13%–19% of term low-birth-weight deliveries, 23%–34% of SIDS, and 5%–7% of preterm-related deaths were attributable to prenatal smoking in the United States.2 Infant exposure to secondhand smoke increases the risk for respiratory tract infections (e.g., bronchitis, pneumonia), ear infections, and death from SIDS.3 Clinicians who assist pregnant women in quitting smoking until the end of pregnancy and remaining quit after delivery can significantly improve the health of mothers and infants.4

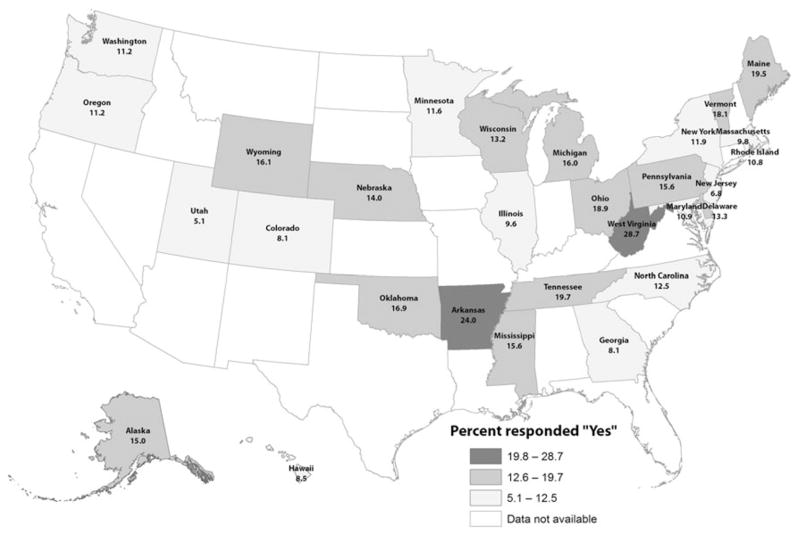

Although the U.S. prevalence of smoking during pregnancy has declined in the past decade,5 prenatal smoking remains unacceptably high, and certain subpopulations of women are particularly at risk. In 2008, data from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) indicated that 12.8% (95% confidence interval [CI] 12.3–13.3) of women in 29 states smoked during the last 3 months of pregnancy.6 The variation ranged from 5.1% in Utah to 28.7% in West Virginia (Fig. 1). Prevalence was highest among women aged 20–24 years (19.3%), Alaska Native women (30.4%), women with <12 years of education (22.5%), and women who were Medicaid-insured (22.1%). Another analysis found young white and Alaska Native women 18–24 years who recently delivered a live infant had high rates of smoking before pregnancy (46.4% and 55.6%), suggesting that younger women at risk of pregnancy in certain racial/ethnic groups may have the greatest need for smoking cessation programs.7 Furthermore, half of women who quit smoking during the last 3 months of pregnancy report relapse to smoking approximately 4 months after delivery.5

FIG. 1.

The percentage of mothers who smoked the last 3 months of pregnancy, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) states, 2008.

Clinical Recommendations

Major clinical guidelines support smoking cessation counseling during pregnancy. The U.S. Public Health Service (USPHS) recommends that clinicians ask all pregnant women about tobacco use and provide augmented, pregnancy-tailored counseling for those who smoke.8 The USPHS recommends that clinicians offer effective tobacco dependence interventions to pregnant smokers at the first prenatal visit as well as throughout the course of pregnancy.8 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that prenatal care providers deliver a brief counseling session for patients who are willing to try to quit smoking.9 ACOG guidance recommends counseling approaches, such as the 5A’s intervention (ask, advise, assess, assist, and arrange), which have been shown to be effective when initiated by healthcare providers.9

Although clinical guidelines consistently recommend screening and counseling by prenatal care providers, only half of pregnant smokers receive counseling.10 Furthermore, only a third of prenatal care providers report delivering recommended cessation interventions in their clinical practice.11,12 Reasons for the low level of cessation counseling include providers’ self-reported lack of awareness of or agreement with existing guidelines, lack of self-efficacy, lack of training, lack of systems to support counseling activities, and lack of patient and provider materials.11–13 Providers reported that they do not have enough training or confidence in prescribing pharmacotherapy to pregnant or breastfeeding women. In addition, many providers report that they have not received formal training on smoking cessation interventions and have stated the desire to learn more about effective cessation interventions and how to implement smoking cessation programs in their offices.

A Web-Based Virtual Clinic

To enhance provider confidence and skills in smoking cessation interventions, “Smoking Cessation for Pregnancy and Beyond: A Virtual Clinic” was developed and updated by Dartmouth College Interactive Media Laboratory in collaboration with ACOG and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Released in the fall of 2011, the training is designed for healthcare professionals to effectively assist pregnant women and women in the childbearing years to quit smoking. The training program teaches a best practice approach for smoking cessation, the 5A’s, and is based on current clinical recommendations from the USPHS and endorsed by ACOG. The program also includes messaging on remaining smoke-free postpartum.

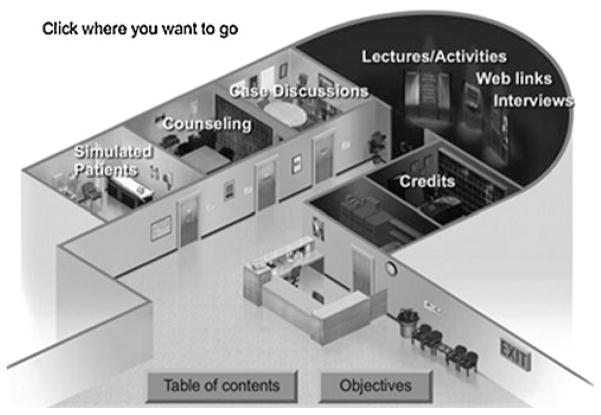

This program offers various learning tools (Fig. 2), including:

FIG. 2.

Virtual clinic screen shot.

Interactive case simulations and comprehensive discussions of the patient visits

Short lecture on relevant topics from leading experts, including former Surgeon General Dr. C. Everett Koop. Lecture topics include: the 5A’s, nature of addiction, pathophysiology and pharmacotherapy, motivational interviewing, and office systems for smoking cessation

Interviews with real patients who have quit

A dedicated website of pertinent links and office resources

In the training, providers can learn about the risks to reproductive health associated with smoking, the benefits of quitting for the mother and fetus, nicotine withdrawal symptoms and how to cope with them, strategies for addressing such patient concerns as weight gain or depressed mood, and issues related to pharmacotherapy use during pregnancy or while breastfeeding. Detailed learning objectives are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Learning Objectives for “Smoking Cessation for Pregnancy and Beyond: A Virtual Clinic”

After completing this activity, the participants will be able to:

|

5A’s, ask, advise, assess, assist, and arrange; 5R’s, relevance, risks, rewards, roadblocks, and repetition; GAPS, goals for your practice, assessment of current services provided, planning how to improve those services, and start-up.

The interactive patient simulations and case discussions allow health professionals to see the application of the 5A’s during prenatal and postpartum visits and with nonpregnant women. Patient simulations include presentation of the patient’s past medical history and current medical condition and the patient’s description of her current smoking behavior. The training format allows the user to go through each step of the 5A’s with the patient. The process is interactive, allowing the user to select options for how to respond to issues as they arise. At the end of each case, the moderator presents a case discussion detailing key learning points.

The training is accredited for up to 4.5 hours of continuing education credits (CME, CNE, CEU, CECH, and CPE). The target audiences are physicians, physician assistants, nurse-midwives, registered nurses, licensed practical/vocational nurses, nurse practitioners, certified health educators, other health educators, pharmacists, health professional students, and other professionals who may interact with women of reproductive age. The cost is $25.00 per user, and group licensing at reduced rates is available. To access the training, please visit www.smokingcessationandpregnancy.org.

Conclusions

Smoking around the time of pregnancy continues to compromise maternal and infant health. This web-based training program can help providers enhance their skills in helping pregnant women quit smoking and remain smoke-free postpartum. Increased quit among pregnant women to improved health for themselves and their offspring.

Acknowledgments

The current, updated version of the training program was developed by the Interactive Media Laboratory, Dart-mouth Medical School (IML) in collaboration with ACOG and was supported by the CDC cooperative agreement 1U48DP001935-01 with the Dartmouth Prevention Research Center. The original version of this program was developed by the IML, with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The original and updated versions of this program were designed, written, directed, and produced by Joseph Henderson, M.D., Professor of Community and Family Medicine, Dartmouth Medical School.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dietz P, England L, Shapiro-Mendoza C, Tong V, Farr S, Callaghan W. Infant morbidity and mortality attributable to prenatal smoking in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39:45–52. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Department of Health Human Services. The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Diseas Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lumley J, Chamberlain C, Dowswell T, Oliver S, Oakley L, Watson L. Interventions for promoting smoking cessation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD001055. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001055.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tong VT, Jones JR, Dietz PM, D’Angelo D, Bombard JM. Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy—Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), United States, 31 sites, 2000–2005. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2009;58:1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed July 6, 2012];PRAMS and smoking. Available at www.cdc.gov/prams/TobaccoandPRAMS.htm.

- 7.Tong VT, Dietz PM, England LJ, et al. Age and racial/ethnic disparities in prepregnancy smoking among women who delivered live births. Prev Chronic Dis. 2011;8:A121. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fiore M, Jaén C, Baker T, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. Rockville, MD: U.S. Dept of Health and Human Services; 2008. Available at http://www.ahrq.gov/path/tobacco.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 9.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion No. 471. Smoking cessation during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116:1241–1244. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182004fcd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tong VT, England LJ, Dietz PM, Asare LA. Smoking patterns and use of cessation interventions during pregnancy. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:327–333. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartmann KE, Wechter ME, Payne P, Salisbury K, Jackson RD, Melvin CL. Best practice smoking cessation intervention and resource needs of prenatal care providers. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:765–770. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000280572.18234.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jordan TR, Dake JR, Price JH. Best practices for smoking cessation in pregnancy: Do obstetrician/gynecologists use them in practice? J Womens Health. 2006;15:400–441. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baxter S, Everson-Hock E, Messina J, Guillaume L, Burrows J, Goyder E. Factors relating to the uptake of interventions for smoking cessation among pregnant women: a systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 2010;12:685–694. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]