Abstract

Background: Our previous three-arm comparative effectiveness intervention in community clinic patients who were not up-to-date with screening resulted in mammography rates over 50% in all arms.

Objective: Our aim was to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the three interventions on improving biennial screening rates among eligible patients.

Methods: A three-arm quasi-experimental evaluation was conducted in eight community clinics from 2008 to 2011. Screening efforts included (1) enhanced care: Participants received an in-person recommendation from a research assistant (RA) in year 1, and clinics followed usual clinic protocol for scheduling screening mammograms; (2) education intervention: Participants received education and in-person recommendation from an RA in year 1, and clinics followed usual clinic protocol for scheduling mammograms; or (3) nurse support: A nurse manager provided in-person education and recommendation, scheduled mammograms, and followed up with phone support. In all arms, mammography was offered at no cost to uninsured patients.

Results: Of 624 eligible women, biennial mammography within 24–30 months of their previous test was performed for 11.0% of women in the enhanced-care arm, 7.1% in the education- intervention arm, and 48.0% in the nurse-support arm (p<0.0001). The incremental cost was $1,232 per additional woman undergoing screening with nurse support vs. enhanced care and $1,092 with nurse support vs. education.

Conclusions: Biennial mammography screening rates were improved by providing nurse support but not with enhanced care or education. However, this approach was not cost-effective.

Introduction

US mammography rates for women are now over 50%,1 although less than 25% of women undergo a second mammogram on at least a biennial schedule.2–3 Repeat mammography screening among “vulnerable” women—those who are uninsured, poor, of minority race/ethnicity, age 65 or older, and/or who live in rural locations—is particularly low.4–10 Developing evidence-based, clinically effective, and cost-effective approaches for repeat mammography is important, as one-time cancer screening will not decrease breast cancer mortality.11–13

Reminder cards, digital video discs (DVDs), phone calls, and counseling have proved clinically effective for improving repeat mammography screening rates among women enrolled in breast health screening programs and large health systems.11,13–17 However, protocols designed to improve repeat mammogram rates among vulnerable populations not enrolled in breast screening programs are needed. Strategies targeting Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs), which disproportionately care for vulnerable populations nationally, offer a practical approach to addressing disparities in repeat mammography screening rates.

We recently completed a three-arm quasi-experimental intervention to evaluate the effectiveness and cost of three strategies designed to improve mammography screening rates of low-income and uninsured populations. Two-thirds of the women were African American, and over half (54%) had low literacy. To ensure that all patients had access to the test, no-cost mammograms were provided to those who lacked insurance. Mammography completion rates for women not up-to-date with screening improved from less than 10% at baseline to 55.7% with enhanced care that included a recommendation for mammography, 51.8% with an intervention that included education, and 65.8% with the education and additional nurse telephone support (p=0.0 37).18 We used this sample to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of these three strategies on biennial mammograms in predominantly rural Louisiana FQHCs.

Materials and Methods

Study design

A three-arm, quasi-experimental comparative effectiveness evaluation was conducted among three Louisiana FQHC networks between May 2008 and August 2011. The target population was five FQHC networks in Louisiana. Three networks agreed to participate in this study. Two networks were involved in ongoing cancer screening programs at the time of the study initiation and were ineligible to participate. Computer-generated random numbers allocated each network to one of three arms: (1) enhanced care with a recommendation by a research assistant (RA) and a clinic nurse scheduling a mammogram immediately after a woman was seen by her primary care physician (PCP), (2) literacy-informed education whereby enhanced care was supplemented by an RA additionally providing brief mammography education, or (3) nurse support with a study nurse conducting the same education provided in the education arm, scheduling a mammogram immediately after a woman was seen by her PCP, and following up with telephone support.

Each participating network was affiliated with multiple clinics assigned to the same study arm as the parent network. In total, two clinics were assigned to enhanced care, two to the educational initiative, and three to the nurse support with educational initiative. After the first year of the study, one additional clinic was enrolled in the enhanced-care arm owing to limited patient recruitment in arm 1 in the first study year. The clinics were located in eight towns in seven parishes. The parent networks each served between 1,162 and 2,386 female patients age 40 and over. Baseline screening mammography rates reported by each clinic prior to initiating the study were between 5% and 9%.

Participants

In year 1, patients were recruited through a multistep process. First, while taking patient vital signs, a medical assistant at each clinic identified potentially eligible female patients by age (≥40 years old) and asked whether they would be willing to talk to an RA about participating in a cancer-screening study prior to the physician encounter. Those interested met with the RA, who screened them for further eligibility: (1) English-speaking, (2) current clinic patient, (3) not requiring screening at an earlier age according to American Cancer Society (ACS) guidelines,19 (4) not up-to-date with 2008 US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)20 screening mammography recommendations (i.e., mammogram every other year beginning at age 40), and (5) not having an acute medical concern.

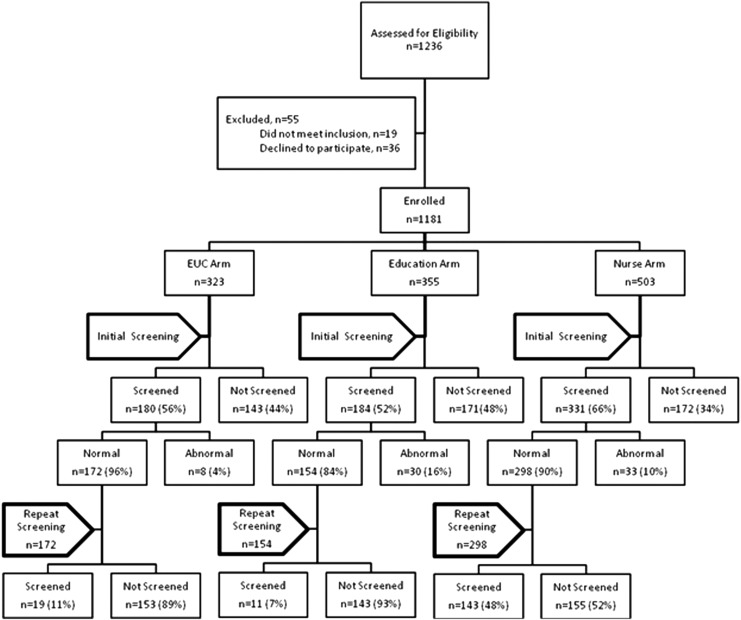

At enrollment, 1,236 patients were identified, 36 (3%) refused to participate, and 19 (2%) were ineligible (see Fig. 1). This left 1,181 enrolled patients with a determined cooperation rate of 96%. A total of 695 patients completed a mammogram within 6 months of enrollment; 624 had a negative result and were therefore eligible for a biennial mammogram. All patients provided consent prior to data collection. The Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center Institutional Review Board approved the study. Each patient received $10 for participation.

FIG. 1.

Flowchart of initial and repeat screening.

Structured interview

The study interview included demographic questions, as well as items about breast cancer and screening mammography, including self-efficacy and barriers from validated questionnaires,21 self-report of previous mammography recommendation and other questions about mammography, and breast cancer from surveys previously used by this team.22 A description of the survey, written on a fourth-grade level and administered orally at enrollment, has been reported previously.23 Literacy was assessed using the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) tool.24 Raw REALM scores (0–66) can be converted into reading-grade levels (<61, below ninth-grade level, an indicator of limited literacy) and (≥61, ninth-grade level or above, an indicator of adequate literacy).

Theoretical framework

The intervention was designed following health literacy best practices and the health learning capacity framework.25–27 The Health Belief Model and social cognitive theories guided content framing in all arms to address salience of breast cancer screening and the need to take action.28–30 The health learning framework guided design of the multimedia educational materials and educational approach by the inclusion of plain-language communication, demonstration, and teach-back techniques to enhance and confirm comprehension in the education and nurse-support arms. These addressed patients' limited knowledge, inadequate understanding, negative beliefs, poor self-efficacy, and lack of motivation.21,31–32 The nurse-support arm was included to determine the added benefit of more in-depth counseling and telephone follow-up support to encourage mammography completion.

The three study arms

Owing to ethical concerns and to ensure that patients in all arms had a recommendation and access to mammography, a recommendation and no-cost mammograms were provided to those without insurance. Prior to initiation of the study, focus groups and individual interviews were conducted with staff, providers, chief executive officers (CEOs), and patients in each clinic. All provided input on the education and counseling; staff and CEOs provided input on study design. Physicians in all clinics requested that the RAs, after enrolling patients and giving a recommendation for mammography, also encourage patients to talk with their PCP about mammography. The PCPs and CEOs in the enhanced usual care (EUC) and education arms suggested regular clinic protocol to follow for scheduling mammograms following the PCP visit and again in 2 years. In the nurse arm, the PCPs, CEOs, and investigators decided that the study nurse would schedule the initial and biennial mammograms.

Enhanced care

At enrollment, a trained, clinic-based RA administered a structured interview while participating women were waiting for a scheduled medical appointment. The RA then gave a recommendation for mammography and a suggestion to talk with the PCP about mammography. Clinic staff scheduled mammograms for participating women following their provider visit. Twenty-four months after mammography completion, participating clinics were sent a list of women who were eligible for biennial screening. Clinic staff followed regular clinic protocol in scheduling the mammogram and following up with results.

Literacy-informed education arm

At enrollment, the clinic RA, who had received training in health literacy techniques, followed the enhanced-care protocol and provided brief education using health literacy best practices, such as using plain language and teach-back to confirm understanding.2–26 The baseline education included the RA's using a pamphlet and brief video as teaching tools. The materials were created by the authors, a video production team, along with input from focus groups of FQHC patients and clinic providers. The video captured actual FQHC patients discussing barriers and facilitators to screening. It showed women encouraging one another to get screened, a physician recommending screening, and a woman getting a mammogram. The pamphlet, written on a fifth-grade level, highlighted risk factors for breast cancer, benefits of regular mammography, and a brief explanation and illustration of the test. The pamphlet included culturally appropriate pictures, text, and testimonials to convey empowering messages to encourage mammography. Iterative cognitive interviews of FQHC patients ensured appeal and cultural and literacy appropriateness of the materials.

As with the enhanced-care arm, 24 months after mammography completion, the investigators sent the clinics a list of women due for biennial screening. Clinic staff followed regular clinic protocol for scheduling mammograms and following up with results.

Nurse-support arm

At enrollment, after the structured interview by a clinic RA, a trained study nurse based at the clinic provided the educational strategy and counseled patients, using motivational interviewing techniques.33 The nurse tracked mammogram completion and, 24 months after completion, called participating women to remind them of and motivate them to undergo biennial screening and to schedule the test. If they did not complete the biennial mammogram, the nurse called again, up to three times, to motivate and reschedule. The nurse tracked results: If results were negative, she sent a letter informing patients that their mammogram was normal; if positive, she called patients to arrange for appropriate follow-up.

Outcome

The primary outcome was completion of a biennial mammogram within 24–30 months of the previous mammogram. Biennial mammograms were documented by the clinic nurse (enhanced-care and education arms) or the research nurse (nurse-support arm) when mammography lab reports were returned to the clinic. In all arms, when a woman completed the mammogram, the hospital sent a report to the clinic, where it was filed and documented in the patient's record.

Statistical analysis

To examine whether patients in the study arms differed on baseline characteristics, generalized linear models with a compound symmetry variance structure within the clinic to account for clustering by clinic (GLMCC) was used for age as a continuous variable and for dichotomous or categorical factors (age categories, education, race, marital status, and literacy level). The identity link was used for continuous variables, the log link was used for dichotomous variables, and the cumulative complementary log-log link was used for categorical variables. Significant variables were used in the multivariate analysis of the outcome. Screening ratios were defined as the ratio of biennial mammography completion rates between two arms. Both screening ratios and pairwise tests for mammography completion were calculated using GLMCC with a log link, with multivariate adjustment for race, education, marital status, whether the patient had seen a doctor in the past 12 months or wanted to know if she had cancer, and self-efficacy.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

Incremental costs for the biennial mammography for the nurse arm over the education arm were 50% of two nurses ($132,850) and mail costs ($22). Incremental costs for the nurse arm over the enhanced-care arm added 10% of a research assistant for $2,800. Costs were assumed to be the same across all towns and parishes. Costs did not include the cost of the mammogram. Costs and number screened were normalized to the reference arm (either education or enhanced care) to account for differences in sample size. Incremental cost-effectiveness was calculated as the total incremental cost of the nurse arm relative to the education arm or the enhanced-care arm divided by the total number of additional persons screened.

Results

Participant demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. The major difference across arms was more African American participants in the nurse arm. Other factors were statistically significant but were relatively modest. All variables in Table 1 with p<0.05 were included as adjustment variables in the comparison of study arms on the primary outcome of biennial mammogram.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Sample at Baseline, Stratified by Study Arm

| Study arm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | All patients (n=624) | Enhanced care (n=172) | Education (n=154) | Nurse (n=298) | p-value |

| Self-efficacy index,a mean (SD) | 28.0 (2.2) | 27.6 (2.4) | 28.8 (2.6) | 27.7 (1.6) | 0.049 |

| Barrier index, mean (SD) | 14.2 (2.9) | 14.5 (3.0) | 14.3 (3.3) | 14.0 (2.7) | 0.39 |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age categories | |||||

| 40–49 | 251 (40) | 60 (35) | 63 (41) | 128 (43) | 0.14 |

| 50–59 | 255 (41) | 79 (46) | 70 (45) | 106 (36) | |

| 60–69 | 87 (14) | 24 (14) | 19 (12) | 44 (15) | |

| 70+ | 31 (5) | 9 (5) | 2 (1) | 20 (7) | |

| Years of education | |||||

| Less than high school | 193 (31) | 60 (35) | 55 (36) | 78 (26) | 0.016 |

| High school grad | 276 (44) | 67 (39) | 71 (46) | 138 (46) | |

| Some college | 112 (18) | 33 (19) | 20 (13) | 59 (20) | |

| ≥College graduate | 43 (7) | 12 (7) | 8 (5) | 23 (8) | |

| Race | |||||

| African American | 405 (65) | 97 (56) | 74 (48) | 234 (79) | <0.0001 |

| Caucasian | 219 (35) | 77 (44) | 80 (52) | 64 (21) | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 207 (33) | 38 (22) | 44 (29) | 125 (42) | 0.028 |

| Married | 180 (29) | 61 (35) | 55 (36) | 64 (21) | |

| Separated | 50 (8) | 16 (9) | 12 (8) | 22 (7) | |

| Divorced | 118 (19) | 34 (20) | 31 (20) | 53 (18) | |

| Widowed | 69 (11) | 23 (13) | 12 (8) | 34 (11) | |

| Literacy level | |||||

| Limited: <ninth grade | 386 (46) | 98 (57) | 49 (32) | 139 (47) | 0.12 |

| Adequate:≥ninth grade | 338 (54) | 74 (43) | 105 (68) | 159 (53) | |

| Seen doctor in past 12 months | 537 (86) | 151 (88) | 139 (90) | 247 (83) | <0.0001 |

| Prior recommendation | 520 (84) | 144 (84) | 134 (87) | 242 (82) | 0.64 |

| Ever had mammogram | 474 (76) | 129 (75) | 114 (74) | 231 (78) | 0.39 |

| Want to know if had cancer | 581 (94) | 165 (96) | 145 (94) | 271 (92) | 0.03 |

The self-efficacy index ranges from 17 to 35, where low numbers mean low self-efficacy; high numbers, high self-efficacy. The barrier index ranges from 6 to 26, where low numbers indicate a low barrier level to obtaining a mammogram; high numbers, a high barrier level.

SD, standard deviation.

Of 624 eligible women, 173, or 28%, completed a biennial mammogram within 30 months. Biennial screening rates were 11.0% in the enhanced-care arm, 7.1% in the education arm, and 48.0% in the nurse-support arm (p<0.0001) (Table 2). After adjustment, patients receiving nurse support were 6.1 times more likely to complete biennial screening mammography (95% confidence interval [CI] 3.63–10.12, p<0.0001) compared to those receiving education. They were 4.0 times more likely to complete screening than were women who had received enhanced care (95% CI 2.83–5.52 p<0.0001). Intraclinic correlation coefficients were 0 for the usual-care arm, 0.003 for the education arm, and 0.04 for the nurse arm.

Table 2.

Primary Outcome Measure: Biennial Mammogram (Screened) Within 13–24 Months

| Study arm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients (n=624) | Enhanced care (n=172) | Education (n=154) | Nurse (n=298) | p-value | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Mammogram (screened) | 173 (28) | 19 (11.0) | 11 (7.1) | 143 (48.0) | <0.0001 |

| No biennial mammogram | 451 (72) | 153 (89.0) | 143 (92.9) | 155 (52.0) | |

| Screening ratio | 1.00 | 0.65 | 3.95 | ||

| 95% CI | (0.40–1.05) | (2.83–5.52) | |||

| p-value | 0.08 | <0.0001 | |||

| Screening ratio | – | 1.00 | 6.06 | ||

| 95% CI | (3.63–10.12) | ||||

| p-value | <0.0001 | ||||

Multivariate analyses controlling for race (African American vs. white), education (<high school, high school or more), marital status (married vs. not married), seen doctor in past 12 months (yes, no/don't know), want to know if had cancer (yes, no/don't know) and self-efficacy.

CI, confidence interval.

When screening ratios among arms were investigated by literacy level, the nurse arm was significantly different from the education arm and the enhanced-care arm in both limited (p<0.0002) and adequate-literacy subgroups (p<0.0002). The incremental cost per additional woman undergoing biennial mammography for the nurse arm relative to the education arm was $1,092 and $1,232 relative to the enhanced-care arm (Table 3).

Table 3.

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

| Nurse (comparison arm) vs. EUC (reference arm) | Nurse (comparison arm) vs. education (reference arm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Additional people screened in comparison arm | |||

| A | Sample size in reference arm | 172 | 154 |

| B | Number screened in reference arm | 19 | 11 |

| C | Sample size in comparison arm | 298 | 298 |

| D | Number screened in comparison arm | 143 | 143 |

| E | Number screened in comparison arm normalized to size of reference arm | 82.5 | 73.9 |

| F | Additional number screened in comparison arm normalized to size of reference arm=E – B | 63.5 | 62.9 |

| Incremental costs of comparison arm | |||

| G | Personnel | $135,650 | $132,850 |

| H | Nonpersonnel | 22 | 22 |

| I | Total incremental costs | 135,672 | 132,872 |

| J | Total incremental costs normalized to size of reference arm | 78,307 | 68,665 |

| Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio=row J/row F | 1,232 | 1,092 |

EUC, enhanced usual care.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first evaluation of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness associated with interventions for promoting biennial mammography screening among patients in both inner-city and rural FQHCs. Unlike other studies promoting repeat mammography among vulnerable populations, our clinics were not participants in county, state, or federally funded cancer-detection programs.10,28,30–31 In our study, biennial screening rates were highest among those who received telephone follow-up support by a nurse manager. Almost half the women who received nurse support sustained screening. However, the cost of over $1,000 per additional woman screened is not feasible in safety-net clinics.

Sustaining mammography in a cost-effective manner in community clinics is challenging. In the first year of our study, up-to-date mammography rates rose to over 50% in all three arms; however, no arm sustained these rates for biennial mammography. Despite the fact that patients incurred no out-of-pocket expenditures getting the mammograms, biennial screening rates reverted to preintervention rates of <10% in the enhanced-care and education arms when clinics followed usual protocol for scheduling mammography. Of note: Although the clinics did not have electronic health records (EHRs) at the time of the study, the investigators provided staff with a list of participants due for biennial screening to prompt scheduling. These findings confirm the still pressing need for FQHCs to develop a sustainable biennial screening approach.

In our study, almost half the “vulnerable women” who received ongoing support, telephone outreach, and mammography scheduling by a dedicated nurse with whom they had at least a 2-year relationship completed biennial mammography. This ongoing support appears to be the only effective approach that worked with women with both low and adequate literacy skills. Our findings are supported by a telephone survey of predominately low-income African American women in the Washington, DC, area, in which O'Malley found that women who reported continuity of healthcare and having a highly compassionate provider were more likely to be adherent with biennial mammography.34 In a different population with teachers enrolled in a state employees health plan, DeFrank found that using mailed and personal or automated phone reminders resulted in effective promotion of repeat mammography.16 The automated calls were more effective and lower in cost.16

Alternative approaches to promote affordable and cost-effective biennial mammography screening among women in rural and inner-city FQHCs in Louisiana will require strategies beyond the three evaluated in our study. Understanding the actual barriers to mammography may facilitate future lower-cost strategies. When our study nurses called patients, the most common barrier to mammography was being unable to attend scheduled mammography appointments and, for those living in rural areas, the closing of a community hospital and subsequent increased distance to the nearest mammography facility. The calls were time consuming, as the nurses attempted to call patients an average of three times before reaching them. Although the calls were usually brief (3–5 minutes), the nurse often had to then call the mammography facility to reschedule the test and then call the patient back to confirm the new appointment. Use of a medical assistant to do the calling would reduce cost by 72%; however, even this approach might be too expensive for a community clinic with limited resources. FQHC networks could consider structuring a collaborative program sharing an assistant to provide all follow-up calls, but this too may not be practical.

In a review of mammography-promoting interventions among women with historically low rates of screening, Legler et al. found that the strongest interventions addressed economic, geographic, and structural barriers as well as personal factors.35 Legler et al. suggested that access-enhancing strategies, such as mobile mammography vans, vouchers, and same-day appointments, are an important complement to individual and systems-directed interventions for women who lack resources to learn about or obtain screening.35 With the reality of the closings of community hospitals and the increased distances to mammography facilities, mobile mammography vans may be particularly beneficial. There may also be incentives for FQHCs to partner with urban health systems to provide state-of-the-art mammography in mobile vans. With the recent federal requirement for community health centers to have EHRs, the amount of staff time needed to identify and track patients due for mammography could be reduced. Future studies should consider using the EHR to generate letters as well as automated calls informing patients that they are due for mammography and, if partnering with a mobile mammography unit, when it will be at their clinic.

Randomization occurred at the FQHC network and not at the patient level. As a result, differences were noted between arms in sociodemographic characteristics. Adjustments were made in the statistical analyses. Other limitations concern the generalizability of the results, which included predominantly African American and low-literacy patients receiving care from FQHCs in one state. However, this is representative of FQHC populations in the southern region of the United States.36 No information was gathered on patients who refused to participate at enrollment, although this was a very small proportion of approached patients (3%). No process measures were collected to evaluate whether the nurses delivered motivational interviewing during the phone calls; however, information was collected on the number of patients reached and the number of calls made to each patient. Finally, it is possible that there may be unmeasured patient factors, such as social support, number of clinic visits, and changes in comorbidity, that could be attributed to repeat screening completion.

Conclusions

In order to be an effective measure for breast cancer detection, mammography must be a regular event; hence, effective, affordable, and cost-effective strategies for improving biennial screening must be developed, particularly in resource-challenged settings. Our study illustrates the need for community clinics to have a systematic approach to regular mammography screening. Telephone outreach by a nurse who schedules a biennial mammography is effective. However, it is not cost-effective in resource-limited settings. Future research should explore leveraging less-expensive clinic staff, distributing the workload over multiple clinics, or possibly automated phone calls and partnering with urban health centers with mobile mammography vans to offset some of the necessary costs to maintain a successful longitudinal screening program that is also affordable.

Acknowledgments

Our study was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (R01-CA115869-05) and in part by 1 U54 GM104940 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, which funds the Louisiana Clinical and Translational Science Center.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Breast cancer facts & figures 2011–2012. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/research/cancerfactsfigures/breastcancerfactsfigures/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures-2011-2012 (accessed on July15, 2014)

- 2.Gierisch JM, Earp JA, Brewer NT, Rimer BK. Longitudinal predictors of nonadherence to maintenance of mammography. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19:1103–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clark MA, Rakowski W, Bonacore LB. Repeat mammography: Prevalence estimates and considerations for assessment. Ann Behav Med 2003;26:201–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rakowski W, Breen N, Meissner H, et al. . Prevalence and correlates of repeat mammography among women aged 55–79 in the year 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Prev Med 2004;39:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang T, Patterson S, Roubidoux M, Duan L. Women's mammography experience and its impact on screening adherence. Psychooncology 2009;18:727–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phillips K, Kerlikowske K, Baker L, Chang SW, Brown ML. Factors associated with women's adherence to mammography screening guidelines. Health Serv Res 1998;33:29–53 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ulcickas Yood M, McCarthy BD, Lee NC, Jacobsen G, Johnson CC. Patterns and characteristics of repeat mammography among women 50 years and older. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 1999;8:595–599 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bobo JK, Shapiro JA, Schulman J, Wolters CL. On-schedule mammography rescreening in the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2004;13:620–630 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith-Bindman R, Miglioretti DL, Lurie N, et al. . Does utilization of screening mammography expliain racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer? Ann Intern Med 2006;144:541–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goel A, George J, Burack RC. Telephone reminders increase re-screening in a county breast screening program. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2008;19:512–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feldstein A, Perrin N, Rosales A, et al. . Effect of a multimodal reminder program on repeat mammogram screening. Am J Prev Med 2009;37:94–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pasick R, Otero-Sabogal R, Nacionales M, Banks PJ. Increasing ethnic diversity in cancer control research: Description and impact of a model training program. J Cancer Educ 2003;18:73–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vernon SW, McQueen A, Tiro J, del Junco DJ. Interventions to promote repeat breast cancer screening with mammography: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009;102:1023–1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quinley J, Mahotiere T, Messina C, Lee TK, Mikail C. Mammography-facility-based patient reminders and repeat mammograms for Medicare in New York State. Prev Med 2004;38:20–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrison T. Response to breast health screening program at a not-for-profit clinic for working poor, uninsured, ethnically diverse women. J Clin Nurs 2012;213:216–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeFrank JT, Rimer BK, Gierisch JM, Bowling JM, Farrell D, Skinner CS. Impact of mailed and automated telephone reminders on receipt of repeat mammograms: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Prev Med 2009;36:459–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Partin MR, Slater JS, Caplan L. Randomized controlled trial of a repeat mammography intervention: Effect of adherence definitions on results. Prev Med 2005;41:734–740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis TC, Rademaker A, Bennett CL, et al. . Improving mammography screening among the medically underserved. J Gen Intern Med 2014;29:628–635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Cancer Society. Breast cancer: Early detection. 2012. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/cancer/breastcancer/moreinformation/breastcancerearlydetection/breast-cancer-early-detection-acs-recs (accessed on October1, 2014)

- 20.US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:716–726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Champion V, Skinner C, Menon U. Development of a self-efficacy scale for mammography. Res Nurs Health 2005;28:329–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis TC, Arnold C, Berkel HJ, Nandy I, Jackson RH, Glass J. Knowledge and attitude on screening mammography among low-literate, low-income women. Cancer 1996;78:1912–1920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis TC, Arnold C, Rademaker A, et al. . Differences in barriers to mammography between rural and urban women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21:748–755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis TC, Long S, Jackson R, et al. . Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: A shortened screening instrument. Fam Med 1993;25:391–395 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weiss BD. Help patients understand: A manual for clinicians, 2nd ed. Chicago: American Medical Association Foundation and American Medical Association, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 26.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. National action plan to improve health literacy. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of health and Human Services, 2010. Available at: http://www.health.gov/communication/hlactionplan/pdf/Health_Literacy_Action_Plan.pdf (accessed on July18, 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolf MS, Wilson EA, Rapp DN, et al. . Literacy and learning in health care. Pediatrics 2009;124(5 suppl):S275–S281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janz NK, Champion VL, Strecher VJ. The Health Belief Model. In: Glanz K, Lewis F, Rimer B, eds. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice, 3rd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenstock I, Strecher V, Becker M. Social learning theory and the Health Belief Model. Health Educ Q 1998;15:175–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav 2004;31:143–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kagawa-Singer M, Valdez Dadia A, Yu MC, Surbone A. Cancer, culture, and health disparities: Time to chart a new course? CA Cancer J Clin 2010;60:12–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McAlearney AS, Reeves K, Tatum C, Paskett ED. Cost as a barrier to screening mammography among underserved women. Ethn Health 2007;12:189–203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hecht J, Borrelli B, Breger R, Defrancesco C, Ernst D, Resnicow K. Motivational interviewing in community-based research: Experiences from the field. Ann Behav Med 2005;9:29–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Malley A, Forrest C, Mandelblatt J. Adherence of low-income women to cancer screening recommendations: The roles of primary care, health insuracne, and HMOs. J Gen Intern Med 2002;17:144–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Legler J, Meissner H, Coyne C, Breen N, Chollette V, Rimer BK. The effectiveness of interventions to promote mammography among women with historically lower rates of screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2002;11:59–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Health Resources and Services Administration. Available at: http://www.hrsa.gov/healthit/toolbox/RuralHealthITtoolbox/Introduction/qualified.html (accessed on July27, 2014)