Abstract

Growing evidence suggests that well-being interventions can be effective. However, it is unclear whether happiness-increasing practices are equally effective for individuals from different cultural backgrounds. To investigate this question, Anglo Americans and predominantly foreign-born Asian Americans were randomly assigned to express optimism, convey gratitude, or list their past experiences (control group). Multi-level analyses indicated that participants in the optimism and gratitude conditions reported enhanced life satisfaction relative to those in the control condition. However, Anglo Americans in the treatment conditions demonstrated larger increases in life satisfaction relative to Asian Americans, while both cultural groups in the control condition showed the least improvement. These results are consistent with the idea that the value individualist cultures place on self-improvement and personal agency bolsters the efforts of Anglo Americans to become more satisfied, whereas collectivist cultures’ de-emphasis of self-focus and individual goals interferes with the efforts of Asian Americans to pursue enhanced well-being.

Keywords: well-being, happiness, life satisfaction, intervention, culture, cultural differences

Throughout the world, subjective well-being (or more colloquially, happiness) is increasingly desired and actively pursued by the majority of people (Diener, 2000). Moreover, evidence is building that the hallmarks of subjective well-being – namely, life satisfaction and positive emotions – are associated with successful outcomes in relationships, careers, and physical health (for a review, see Lyubomirsky, King, & Diener, 2005). Given the heightened emphasis on the pursuit of happiness worldwide, along with the advantages happy people seem to enjoy relative to their less happy peers, an important question is whether it is even possible to sustainably improve an individual’s well-being.

Initial evidence suggests that, at least in the short-term, well-being interventions can be successful. For example, activities like expressing gratitude (Emmons & McCullough, 2003; Froh, Sefick, & Emmons, 2008; Lyubomirsky, Dickerhoof, Boehm, & Sheldon, 2009; Lyubomirsky, Sheldon, & Schkade, 2005), imagining one’s ideal future life (King, 2001), counting acts of kindness (Sheldon, Boehm, & Lyubomirsky, in press; Otake, Shimai, Tanaka-Matsumi, Otsui, & Fredrickson, 2006), using one’s personal strengths (Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005), pursuing need-satisfying goals (Sheldon, Abad et al., in press), and meditating (Fredrickson, Cohn, Coffey, Pek, & Finkel, 2008) boost well-being.

An important criticism of the limited number of randomized well-being interventions published thus far is that they have employed only Western participants (see Otake et al., 2006, for an exception). Of course, “the pursuit of happiness” is a staple ideology in Western – and particularly North American – culture. In addition, people from individualist cultures tend to emphasize an autonomous and independent self over the needs of the larger group, and are inclined to be motivated by personal needs and goals (Triandis, 1995). By contrast, non-Western or collectivist cultures are likely to downplay the significance of happiness (Diener & Suh, 1999). Instead, such cultures emphasize collective harmony and tend to be motivated by the norms and duties of their family or group (Triandis, 1995). Differences in cultures are also evident in the way people form judgments about well-being: Those from individualist cultures base their life satisfaction more on intrapersonal than interpersonal factors, whereas those from collectivist cultures do the reverse (Suh, Diener, Oishi, & Triandis, 1998). Moreover, cultural background moderates the influence of the determinants of well-being – for example, self-esteem is more important to the well-being of people in individualist versus collectivist cultures (Diener & Diener, 1995). In sum, norms in collectivist cultures are less supportive of self-expression, self-improvement, and the pursuit of individual goals. This evidence suggests that traditional individually-focused happiness interventions may be less effective for those belonging to collectivist cultures versus individualist cultures.

To explore this idea, we designed a 6-week randomized controlled intervention to test whether two happiness-enhancing strategies – optimistically thinking about the future and writing letters of gratitude – would produce equivalent gains in well-being for Anglo Americans and predominantly foreign-born Asian Americans. In line with previous findings, we hypothesized that individuals randomly assigned to either express optimism or gratitude (i.e., the treatment groups) would demonstrate increases in well-being relative to a control group. However, we expected these findings to be moderated by culture, whereby Anglo Americans in the treatment groups would demonstrate the greatest gains in well-being, compared with Asian Americans in the treatment groups and all participants in the control group. Notably, we selected the two treatment activities of practicing optimism and gratitude because the former is focused on individual wishes and desires, whereas the latter more directly invokes social relationships. Accordingly, we hypothesized that the gratitude condition would confer greater advantages in well-being to Asian Americans than would the optimism condition.

Method

Participants

Two hundred twenty community-dwelling individuals (116 female, 104 male) participated in this study.1 Ages ranged from 20 to 71 years (M = 35.62, SD = 11.36). Forty-eight percent of the participants were married and, across the entire sample, the average participant had one child (range from 0 to 5, SD = 1.19 children). The highest level of education completed by the majority of participants was college (56%), with 25% completing graduate school and 19% completing only high school. Approximately half the sample was of Asian descent (49%) and half was of Anglo American descent (51%). Seventy-eight percent of the Asian Americans were born in foreign countries. Of these, 47% were born in China, 13% in Vietnam, 11% in Korea, 8% in Taiwan, and 21% in other Asian countries (e.g., Singapore, Japan).2

Participants were recruited through advertisements on community-based websites, fliers posted throughout communities in Southern California, and a Chinese-language newspaper advertisement targeting Chinese immigrants in Southern California. The majority of participants, however, were recruited online and therefore originated from different regions of the United States.3 The study was described as potentially improving mental and physical health so that participants’ expectations across all conditions would be equivalent at the start of the experiment. If participant’s completed at least 6 out of the 7 study sessions (described below), they received $60 in compensation.

Design and Procedure

A 2 (cultural background: Asian-American, Anglo-American) X 3 (condition: optimism, gratitude, control) factorial design was used. Participants were randomly assigned to practice optimism (n = 74), express gratitude (n = 72), or list their past week’s experiences (n = 74; i.e., control). Those in the optimism condition were asked to write about their best possible life in the future (with regards to their family, friends, romantic partner, career, health, and hobbies) and imagine that everything had gone as well as it possibly could (cf. King, 2001). Participants in the gratitude condition were asked to write letters of appreciation to friends or family members who had done something for which they were grateful (adapted from Seligman et al., 2005). Those in the control condition were asked to outline what they had done in the past week. The control activity was described as an organizational task to enhance the plausibility of this condition as a positive exercise.

Participants received initial instructions from the researchers by phone and e-mail. The rest of the experiment was conducted over the Internet through a password-secured website. The first assessment consisted of demographic information and our outcome of interest, the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Diener, Emmons, Larsen, & Griffin, 1985).4 The SWLS is a 5-item scale designed to assess the cognitive component of subjective well-being. Items such as “In most ways my life is ideal” were rated on 7-point Likert-type scales, which were then averaged such that higher scores indicated greater life satisfaction. Alphas for the SWLS ranged from .91 to .94 in this study.5 Following these measurements, participants completed the first of six writing manipulations, each lasting 10 min once a week for 6 weeks. Following the sixth, and last, week of the intervention, participants again completed the SWLS for an immediate post-intervention assessment. To evaluate any lingering effects stemming from the intervention, participants completed the SWLS one month post-intervention.

Analytic Approach

To account for within-person and between-person changes in satisfaction across time, we used multilevel modeling techniques estimated with SAS Proc Mixed. As recommended by Singer and Willett (2003), we started with unconditional models. Age, centered at the mean, was a significant predictor of initial life satisfaction, such that older participants reported lower life satisfaction than younger ones. Because of this difference, age was included as a covariate in all subsequent models.6 We then compared the baseline unconditional growth model (composite model: Yij = γ00 + γ01Agei + γ10Timeij + [εij + ζ0i + ζ1iTimeij]; Level 1 model: Yij =π0i + π1iTimeij + εij; Level 2 models: π0i = γ00 + γ;01Agei + ζ0i and π1i = γ10 + ζ1i) to hypothesis-testing models (see Table 1 for all parameter estimates). Time was coded such that the baseline equaled 0, immediate post-intervention equaled 5, and the 1-month follow-up equaled 6. Variables representing condition and cultural background were entered as between-subjects predictors at the second level of the models. Condition was dummy coded with the control group as the reference. Similarly, cultural background was dummy coded with the Anglo-American group as the reference.

Table 1.

Model Parameters (Standard Errors) and Goodness of Fit

| Effect | Parameter | Unconditional Growth | Optimism vs Gratitude vs Control | Treatment vs Control | Treatment vs. Control Moderated by Cultural Background | Optimism vs. Gratitude vs. Control for Cultural Background | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects | Intercept | γ00 | 4.47*** (.09) | 4.41*** (.16) | 4.41*** (.16) | 4.72*** (.24) | 4.47*** (.19) |

| Time | γ10 | ..01 (.01) | −.03~ (.02) | −.03~ (.02) | −.03 (.02) | −.02 (.02) | |

| Age | γ01 | −.02(.007)* | −.02** (.008) | −.02** (.008) | −.03*** (.008) | −.03*** (.008) | |

| Treatment | γ02 | -- | -- | .09 (.20) | −.29 (.28) | -- | |

| Optimism | γ03 | -- | .22 (.23) | -- | -- | .22 (.22) | |

| Gratitude | γ04 | -- | −.04 (.23) | -- | −.05 (.23) | ||

| Cultural Background | γ05 | -- | -- | -- | −.59~ (.33) | −.11 (.20) | |

| Treatment * Time | γ11 | -- | -- | .06** (.02) | .1*** (.03) | -- | |

| Optimism * Time | γ12 | -- | .05* (.02) | -- | -- | .09** (.03) | |

| Gratitude * Time | γ13 | -- | .07** (.02) | -- | -- | .08** (.03) | |

| Cultural Background * Time | γ14 | -- | -- | -- | .01 (.03) | −.008 (.03) | |

| Treatment * Cultural Background | γ15 | -- | -- | -- | .73~ (.39) | -- | |

| Treatment * Cultural Background * Time | γ16 | -- | -- | -- | −.08~ (.04) | -- | |

| Optimism * Cultural Background * Time | γ17 | -- | -- | -- | -- | −.07~ (.04) | |

| Gratitude * Cultural Background* Time | γ18 | -- | -- | -- | -- | −.02 (.04) | |

| Random Effects | Level 1 | σ2ε | .29*** (.03) | .29*** (.03) | .29*** (.03) | .29*** (.03) | .29*** (.03) |

| Level 2 | σ20 | 1.60*** (.18) | 1.59*** (.18) | 1.60*** (.18) | 1.58*** (.18 | 1.59*** (.18) | |

| σ21 | .008*** (.003) | ) .007*** (.002 | .007** (.003) | .006** (.002) | .006** (.002) | ||

| Goodness of Fit | Deviance | 1736.50 | 1724.20 | 1726.10 | 1714.70 | 1715.40 | |

| Akaike Information Criterion | 1750.50 | 1746.20 | 1744.10 | 1740.70 | 1745.40 | ||

| Bayesian Information Criterion | 1774.30 | 1783.60 | 1774.60 | 1784.90 | 1796.30 |

Note:

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Results

Asian Americans and Anglo Americans did not differ in life satisfaction prior to beginning the intervention (t = .91, ns), nor did the three experimental groups (F = .90, ns). This latter, nonsignificant finding suggests that random assignment to condition was successful. To replicate previous findings, we examined the effect of condition on trajectories of life satisfaction. Relative to the baseline model, there was a significant improvement of fit when condition was included in the model,χ2(4) = 12.3, p < .05. Specifically, participants who expressed optimism (γ12 = .05, SE = .02, t(199) = 1.98, p < .05) or gratitude (γ13 = .07, SE = .02, t(199) = 3.03, p < .01) showed increases in satisfaction across time relative to control participants. We found a similar pattern after collapsing together the two treatment conditions and comparing them with the control condition – namely, those in the control condition did not receive the boost that those in the treatment conditions did (γ11 = .06, SE = .02, t(199) = 2.87, p < .01; comparison with baseline model: χ2(2) = 10.4, p < .01).

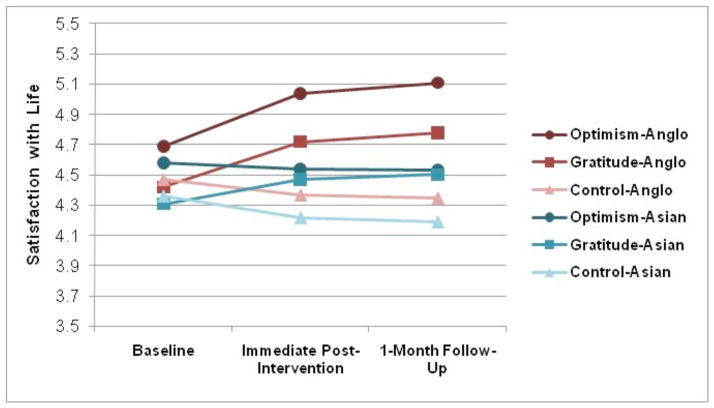

Notably, the effect of condition was qualified by cultural background (γ16 = −.08, SE = .04, t(199) = .−1.91; p = .057; comparison with previous model: χ2(4) = 11.40, p = .02). Asian Americans in either of the two treatment conditions displayed little change in satisfaction across time, whereas Asian Americans in the control condition actually showed very small decrements in their satisfaction. By comparison, the Anglo Americans in either of the two treatment conditions demonstrated the biggest gains in satisfaction of all the groups, and the Anglo Americans in the control condition showed a slight decrease or no change.

Moreover, in line with our predictions, a trend emerged for Asian Americans to derive less benefit from expressing optimism (γ17 = −.07, SE = .04, t(199) = −1.68, p = .09) than from expressing gratitude (γ18 = −.02, SE = .04, t(199) = −.55, ns). That is, Asian Americans in the gratitude condition showed slight increases in life satisfaction across time, whereas Asian Americans in the optimism condition showed essentially no change (see Figure 1). These marginally significant findings are consistent with the idea that writing letters of gratitude – a practice that presumably emphasizes social connectedness – may be more fitting for individuals for whom social relationships and social harmony are cultural priorities.

Figure 1.

Trajectories of life satisfaction across time for Anglo Americans in the optimism condition, Anglo Americans in the gratitude condition, Anglo Americans in the control condition, Asian Americans in the optimism condition, Asian Americans in the gratitude condition, and Asian Americans in the control condition (with age shown at its average).

Discussion

Consistent with previous research, our experimental intervention demonstrated that regularly practicing optimism and conveying gratitude over the course of 6 weeks enhances life satisfaction relative to writing about weekly experiences. In addition, the study provided an opportunity to examine whether participants’ cultural background would impact the effects of such activities on well-being. Our results were consistent with the notion that Western culture’s emphasis on self-improvement and personal agency – and a fixation with the pursuit of happiness in particular – would bolster the efforts of its members to enhance well-being, whereas Asian culture’s relatively lesser valuation of happiness and lesser focus on individual (as opposed to group) goals would provide weaker support and endorsement of its members’ happiness-boosting activities. Specifically, we found that Anglo Americans benefited more from our intervention than did predominantly foreign born Asian Americans, despite the fact that both groups began the intervention with equivalent levels of life satisfaction. Notably, however, this effect was most pronounced in the two treatment conditions and not in the control condition, even though all participants were initially led to believe that the activity in which they were to engage would bolster well-being. Furthermore, in accordance with our hypotheses, Asian Americans seemed to benefit marginally more from conveying gratitude to people in their lives rather than expressing optimism about their personal futures.

These findings suggest that the pursuit of happiness can be fruitful if done under optimal conditions. That is, people need both a “will” (i.e., the desire and motivation to become happier) and a “way” (i.e., an efficacious happiness-boosting activity or positive practice; Lyubomirsky et al., 2009). In this study, cultural background – and the inherent prescriptions and support derived from it – impacted participants’ “will” to exert effort into enhancing well-being. However, although Anglo Americans may have had more “will” to change than Asian Americans, that is not sufficient. Individuals must also possess a proper “way” by which to achieve gains in well-being. Indeed, Anglo Americans reported greater boosts in life satisfaction than did Asian Americans, but only when the Anglo Americans engaged in an effective activity like expressing optimism or gratitude (as opposed to a placebo activity). This finding suggests that participating in empirically-established positive activities and originating from a culture that endorses the pursuit of individual well-being may be two keys for achieving enhanced happiness. However, this conclusion raises important ethical questions: Should people from non-Westernized or collectivist cultures be encouraged to pursue ever-greater personal well-being? Furthermore, should they achieve this by means that do not fit their cultural tradition? As noted above, Asian Americans showed a trend towards benefitting more from expressing gratitude than thinking optimistically. Because expressing gratitude may more closely align with Asian-rooted values and priorities, the activity may have been viewed by Asian Americans as a more appropriate “way” to achieving happiness and, hence, they experienced a stronger “will” to do so. Moreover, it is worth mentioning that other characteristics of Asian Americans – such as their relatively higher levels of pessimism – may be advantageous in a collectivist society, providing another “way” (for example, via problem-solving coping strategies) by which Asian Americans can experience both success and well-being (Chang, 1996). This study’s implications caution against the assumption that all individuals have the same will to increase personal well-being and that all individuals benefit from the same way of pursuing it.

Limitations

Due to the relatively small sample sizes for specific groups of Asian Americans (e.g., Korean, Chinese, Japanese), we combined all (primarily East) Asian participants into a larger, more heterogeneous group. Although some cultural differences undoubtedly exist among distinct Asian groups, we felt that East Asia’s broad emphasis on collective goals – as opposed to a focus on individual pursuits and personal well-being – would be captured by a mixed group of Asian-Americans. In other words, the similarities among these cultures (at least those relevant to this research) likely outweigh the differences. To be sure, we are not the first researchers to use a heterogeneous sample when examining cultural differences (e.g., English & Chen, 2007). Moreover, it would be valuable for future researchers to investigate well-being interventions in samples within Asian countries rather than using Asian Americans as a proxy (as we have done here and others have done previously; e.g., Tsai & Levenson, 1997), because, relative to Asian Americans, Asians may manifest greater differences with Anglo Americans.

Another limitation concerned the self-reported dependent variable in this study – a methodology that raises potential social desirability and response biases. Although well-being is, by definition, a subjective construct, future research could be strengthened by additional measurement methods including peer report, experience sampling, facial expression coding, evaluation of written text, and even physiological indicators. Moreover, consideration of other aspects of subjective well-being in happiness-boosting interventions (e.g., high and low arousal positive and negative emotions) may reveal different underlying processes, outcomes, or cultural differences. Given that Anglo Americans and Asian Americans value affective states differently – for example, Anglo Americans tend to strive for high-arousal affect and Asian Americans for low-arousal affect (Tsai, 2007) – it is critical that future research includes outcomes that capture the meaning of well-being for both individualist and collectivist cultures.

Concluding Remarks

Taken together, our findings suggest that although most individuals pursuing happiness will benefit by regularly practicing gratitude and optimism, those benefits may be mitigated by cultural norms and values that fail to support their efforts. Whether other intervention activities, like reflecting on fulfilling one’s obligations and duties or working to feel understood by others (Lun, Kesebir, & Oishi, 2008), may be more successful in bolstering personal happiness among members of collectivist cultures remains a question for future research.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Mental Health R01 Grant No. 5 R01 MH065937-04 to SL and KMS. The authors would like to thank Sandra Arceo, Joseph Chancellor, Monica Ramirez, Angelina Seto, and Jerome Sinocruz for assisting with data coding, participant recruitment, and other aspects of this research. We are also grateful to Chandra Reynolds for her statistical assistance and two anonymous reviewers for their suggestions.

Footnotes

The original sample consisted of 348 participants. Twenty-six individuals who were not Asian or Anglo were eliminated, as were 83 individuals who missed two or more study sessions and one individual with baseline well-being that exceeded three standard deviations. (Those who missed two or more study sessions did not differ from other participants in terms of baseline well-being, condition, cultural background, age, or sex.) To compare models within multi-level modeling, the same individuals must contribute to each model. Hence, those with missing data on critical variables were excluded, yielding a total sample size of 220.

We were unable to analyze participants from each country separately due to small sample sizes.

Using the Internet to conduct research has become increasingly common. Internet-based studies tend to draw on relatively diverse samples and yield comparable findings to those using more traditional methods (Gosling, Vazire, Srivastava, & John, 2004).

We focused on the outcome of life satisfaction because it is a relatively stable component of subjective well-being compared with positive emotions, which may be more transitory and based on immediate situational influences.

It is important to ensure that items on the SWLS would be interpreted similarly by both our cultural groups. Because Oishi (2006) previously found sufficient evidence for measurement equivalence of the SWLS in samples of American and Chinese college students, we felt that the equivalence would be adequate in our study.

No other demographic characteristics were significant predictors of baseline satisfaction. in satisfaction

Contributor Information

Julia K. Boehm, University of California, Riverside

Sonja Lyubomirsky, University of California, Riverside.

Kennon M. Sheldon, University of Missouri-Columbia

References

- Chang EC. Cultural differences in optimism, pessimism, and coping: Predictors of subsequent adjustment in Asian American and Caucasian American college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1996;23:113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E. Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist. 2000;55:34–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Diener M. Cross-cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:653–663. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.68.4.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1985;49:71–75. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener E, Suh E. National differences in subjective well-being. In: Kahneman D, Diener E, Schwarz N, editors. Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1999. pp. 434–452. [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA, McCullough ME. Counting blessings versus burdens: An experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:377–389. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.84.2.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English T, Chen S. Culture and self-concept stability: Consistency across and within contexts among Asian Americans and European Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93:478–490. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.3.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Cohn MA, Coffey KA, Pek J, Finkel SM. Open hearts build lives: Positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95:1045–1062. doi: 10.1037/a0013262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froh JJ, Sefick WJ, Emmons RA. Counting blessings in early adolescents: An experimental study of gratitude and subjective well-being. Journal of School Psychology. 2008;46:213–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosling SD, Vazire S, Srivastava S, John OP. Should we trust web-based studies? A comparative analysis of six preconceptions about Internet questionnaires. American Psychologist. 2004;59:93–104. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King LA. The health benefits of writing about life goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2001;27:798–807. [Google Scholar]

- Lun J, Kesebir S, Oishi S. On feeling understood and feeling well: The role of interdependence. Journal of Research in Personality. 2008;42:1623–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Dickerhoof R, Boehm JK, Sheldon KM. Becoming happier takes both a will and a proper way: An experimental longitudinal intervention to boost well-being. 2009 doi: 10.1037/a0022575. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, King LA, Diener E. The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:803–855. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Sheldon KM, Schkade D. Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology. 2005;9:111–131. [Google Scholar]

- Oishi S. The concept of life satisfaction across cultures: An IRT analysis. Journal of Research in Personality. 2006;40:411–423. [Google Scholar]

- Otake K, Shimai S, Tanaka-Matsumi J, Otsui K, Fredrickson BL. Happy people become happier through kindness: A counting kindness intervention. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2006;7:361–375. doi: 10.1007/s10902-005-3650-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP, Steen TA, Park N, Peterson C. Positive psychology progress: Empirical validation of interventions. American Psychologist. 2005;60:410–421. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon KM, Abad N, Ferguson Y, Gunz A, Houser-Marko L, Nichols CP, Lyubomirsky S. Persistent pursuit of need-satisfying goals leads to increased happiness: A 6-month experimental longitudinal study. Motivation and Emotion in press. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon KM, Boehm JK, Lyubomirsky S. Variety is the spice of happiness: The hedonic adaptation prevention (HAP) model. In: Boniwell I, David S, editors. Oxford handbook of happiness. Oxford: Oxford University Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Suh E, Diener E, Oishi S, Triandis HC. The shifting basis of life satisfaction judgments across cultures: Emotions versus norms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:482–493. [Google Scholar]

- Triandis HC. Individualism and collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL. Ideal affect: Cultural causes and behavioral consequences. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2007;2:242–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai JL, Levenson RW. Cultural influences of emotional responding: Chinese American and European American dating couples during interpersonal conflict. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1997;28:600–625. [Google Scholar]