Abstract

Influenza virus (IFV) can evolve rapidly leading to genetic drifts and shifts resulting in human and animal influenza epidemics and pandemics. The genetic shift that gave rise to the 2009 influenza A/H1N1 pandemic originated from a triple gene reassortment of avian, swine and human IFVs. More minor genetic alterations in genetic drift can lead to influenza drug resistance such as the H274Y mutation associated with oseltamivir resistance. Hence, a rapid tool to detect IFV mutations and the potential emergence of new virulent strains can better prepare us for seasonal influenza outbreaks as well as potential pandemics. Furthermore, identification of specific mutations by closely examining single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in IFV sequences is essential to classify potential genetic markers associated with potentially dangerous IFV phenotypes. In this study, we developed a novel R library called “SNPer” to analyze quantitative variants in SNPs among IFV subpopulations. The computational SNPer program was applied to three different subpopulations of published IFV genomic information. SNPer queried SNPs data and grouped the SNPs into (1) universal SNPs, (2) likely common SNPs, and (3) unique SNPs. SNPer outperformed manual visualization in terms of time and labor. SNPer took only three seconds with no errors in SNP comparison events compared with 40 hours with errors using manual visualization. The SNPer tool can accelerate the capacity to capture new and potentially dangerous IFV strains to mitigate future influenza outbreaks.

Introduction

Influenza virus (IFV), a rapidly evolving virus in the orthomyxoviridae family, causes frequent epidemics and occasional pandemics. The diversity of the IFV genome generates mixtures of viral subpopulations, which subsequently can lead to the emergence of new virulent strains. Genetic divergence of IFV sequences can be driven by pressure from host immunity and host cell factors [1]. IFV evolves through several mechanisms including RNA recombination, point mutation or antigenic drift, and gene reassortment or genetic shift [2]. There are three types of IFVs (influenza A, B and C) with human disease most commonly caused by influenza A/H3N2, A/H1N1 and B. A full length RNA genome of influenza A is approximately 13.6 kb; influenza B is about 14.6 kb. The full genomic structure is composed of eight fragments with approximate lengths of 2341 nucleotides (nt) for RNA polymerase PB1 unit; 2300 nt for RNA polymerase PB2; 2233 nt for RNA polymerase PA; 1765 nt for hemagglutinin (HA); 1565 nt for nucleoprotein (NP); 1413 nt for neuraminidase (NA) with additional NB protein in influenza B; 1027 nt for matrix (M); 890 nt for nonstructural protein (NS) including NS1 and NS2 proteins.

Close monitoring of current circulating strains is crucial to evaluate IFV evolution as well as the possible detection of novel virulent and drug resistant viral strains. This information is essential for determining seasonal influenza vaccine design and composition. Therefore, a technique to identify the signature sequence or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) of viruses from the large amount of sequence information typically generated using next-generation sequencing (NGS) is essential to evaluate the sequence signatures in viral subpopulations associated with virulent or drug resistant phenotypes.

NGS [3], also known as high-throughput sequencing, is a powerful sequencing technique often used to obtain large amounts of genomic sequences to investigate specific questions about an organism’s genetic information. Particularly in viruses, this methodology has been adopted for diagnosis and advanced investigations to detect novel mutations and evolving quasispecies [4]. Analyzing SNPs by manual visualization is time consuming and resource intensive. A computational program to compare viral SNPs would provide an efficient tool compared to manual analysis.

R [5] is an open source statistics programming language and environment (http://www.r-project.org/). A wide variety of packages are provided by R, especially bioinformatics packages such as Bioconductor [6] (www.bioconductor.org), GenABEL [7] and ParallABEL [8] (http://www.genabel.org/packages). MySQL (http://www.mysql.com/) is a well known free database management software useful for storing and retrieving SNPs data using SQL command [9]. MySQL can be manipulated by R using RMySQL [10], a database interface and MySQL driver for R.

In this article, we present the development of the “SNPer” library, a new R library for identification of IFV mutations by differentiation of SNPs among viral subpopulations. “SNPer” is named to denote the action of searching for SNPs in a MySQL database.

Methods

Operating System and Computer Software for Input Data Preparation

A personal computer running CentOS (Community Enterprise Operating System) version 6.3 (http://www.centos.org/download/) was utilized for data analysis. The computer consisted of an Intel icore i5-2400 (3.10 GHz) processor and 4 GB RAM. This computer also provided R program version 3.0.2, RMySQL library version 0.9–3, and MySQL 5.1.67, which were utilized as components by the SNPer library.

SNPs data of three different influenza A/H3N2 viral subpopulations obtained by NGS and published in Sequence Read Archive (SRA) and GenBank [11–12] were used to create an input data file to measure the performance of SNPer. The IFV genomic information of NGS sequence read data as described in detail in Rutvisuttinunt et al. 2014 [12] including viral subpopulations from sample #VIROAF1 (GenBank accession number KJ577146-KJ577153), VIROAF2 (KJ577154-KJ577161) and VIROAF6 (KJ577186-KJ577193) were downloaded from the database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra and http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/). Each subpopulation had eight fragments: PB2, PB1, PA, HA, NP, NA, M and NEP. The SNPs data of the three IFV subpopulations in csv files were created by Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) [13] and Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) [14–15] from the raw fastq files.

Table 1 illustrates an example of SNPs data of the HA gene fragment from VIROAF1 contained in “AF1_HA.csv” file. A *.csv file contained SNPs information of the sequence reads of interest after being aligned with the reference genome, and the fields of each line were separated by commas and enclosed within double quotation marks. The specific “AF1_HA.csv” file was created by MiSeq Reporter aligning sequence reads [13] with the NGS data of influenza A/H3N2 subpopulation 1 against the HA gene of the reference genome influenza A/H3N2 (GenBank CY121792). The Call column presents the alleles of the SNPs. For example, the first SNP at location 51 is A51G (VIROAF1 contains allele G while reference contains allele A at position 51 of HA gene fragment).

Table 1. Detected SNPs in HA gene fragment from sample #VIROAF1 (“AF1_HA.csv”).

| # | Sample ID | Sample Name | Chr | Position | Score | Variant Type | Call | Frequency | Depth | Filter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | H3N2_CY121792_HA.seq | 51 | 13099 | SNP | A->[G/G] | 1 | 426 | LowGQ |

| 2 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | H3N2_CY121792_HA.seq | 72 | 16707 | SNP | C->[T/T] | 1 | 567 | LowGQ |

| 3 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | H3N2_CY121792_HA.seq | 146 | 23020 | SNP | A->[G/G] | 1 | 864 | LowGQ |

| 4 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | H3N2_CY121792_HA.seq | 182 | 23194 | SNP | G->[A/A] | 1 | 872 | LowGQ |

| 5 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | H3N2_CY121792_HA.seq | 191 | 23154 | SNP | C->[T/T] | 1 | 852 | LowGQ |

| 6 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | H3N2_CY121792_HA.seq | 285 | 17047 | SNP | C->[T/T] | 1 | 620 | LowGQ |

| 7 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | H3N2_CY121792_HA.seq | 308 | 16337 | SNP | T->[A/A] | 1 | 580 | LowGQ |

| 8 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | H3N2_CY121792_HA.seq | 405 | 21306 | SNP | A->[G/G] | 1 | 791 | LowGQ |

| 9 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | H3N2_CY121792_HA.seq | 413 | 20528 | SNP | G->[A/A] | 1 | 760 | LowGQ |

| 10 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | H3N2_CY121792_HA.seq | 456 | 20446 | SNP | C->[T/T] | 1 | 768 | LowGQ |

Each line describes the SNPs at each position in the HA gene fragment of VIROAF1. For instance, position 51 of the HA gene in VIROAF1 is G while the reference allele is A.

Executing SNPer

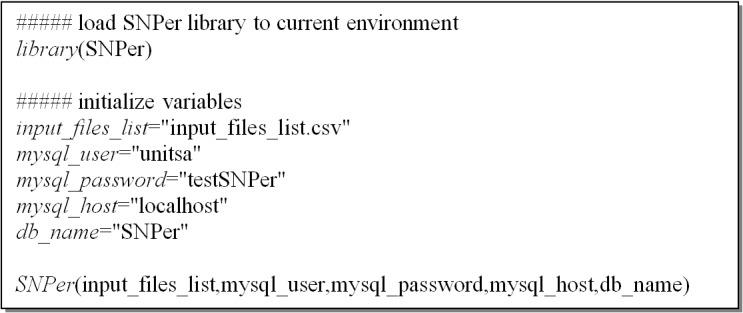

After installing the SNPer package, users can use SNPer to compare IFV SNPs by executing the SNPer function. An example of SNPer usage is shown in Fig 1. The user can change the variables including input_files_list (a file contained the list of SNPs files), mysql_user (a user name in MySQL), mysql_password (a password for the user name), mysql_host (the host name of MySQL), and db_name (the database name for storing SNPs data). The SNPer database must be created by the user before executing SNPer.

Fig 1. An example of SNPer usage.

The user loads the SNPer library to current environment before using the SNPer function.

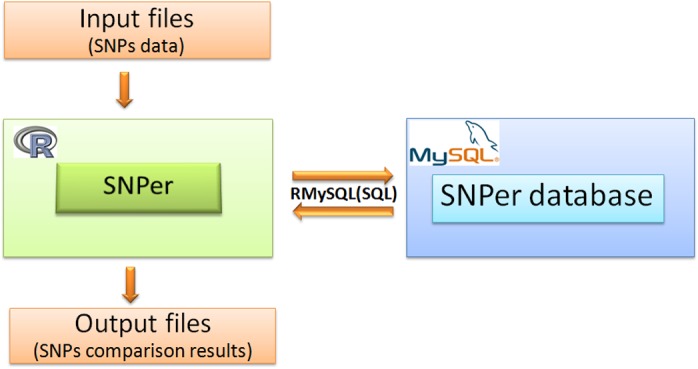

The workflow for SNPs comparison is presented in Fig 2. The SNPs data in input files is processed by the SNPer library under the R program. SNPer uses RMySQL library and SQL commands to create three tables of the SNPer database including sp1, sp2 and sp3 [Table 2]. These tables store SNPs data of each viral subpopulation in the SNPer database. For instance, the sp1 table stores the SNPs data of the HA fragment of the first IFV subpopulation (VIROAF1) contained in “AF1_HA.csv” file, the sp2 table stores the SNPs data of the HA fragment of the second IFV subpopulation (VIROAF2) contained in “AF2_HA.csv” file, and the sp3 table stores the SNPs data of the HA fragment of the third IFV subpopulation (VIROAF6) contained in “AF6_HA.csv” file. SNPer executes data according to the list of subpopulations illustrated in Table 2. The SNPs data from “AF1_HA.csv”, “AF2_HA.csv” and “AF6_HA.csv” are pulled from the SNPer database for SNPs comparison by SNPer.

Fig 2. SNPs comparison workflow.

SNPer, an R library, analyzes SNPs data using RMySQL and MySQL producing SNPs comparison data as its output.

Table 2. List of SNP input files ("input_files_list.csv") to be compared by SNPer.

| sp1 | sp2 | sp3 |

|---|---|---|

| AF1_HA.csv | AF2_HA.csv | AF6_HA.csv |

| AF1_M.csv | AF2_M.csv | AF6_M.csv |

| AF1_NA.csv | AF2_NA.csv | AF6_NA.csv |

| AF1_NEP.csv | AF2_NEP.csv | AF6_NEP.csv |

| AF1_NP.csv | AF2_NP.csv | AF6_NP.csv |

| AF1_PA.csv | AF2_PA.csv | AF6_PA.csv |

| AF1_PB1.csv | AF2_PB1.csv | AF6_PB1.csv |

| AF1_PB2.csv | AF2_PB2.csv | AF6_PB2.csv |

SNPs from eight fragments of sp1, sp 2 and sp3 were compared by SNPer. Each computational SNPs comparison among three viral subpopulations was conducted according to the name of the files listed in each row. For instance, for row #1, SNPer compared the SNPs data in file “AF1_HA.csv” of population 1 (sp1), “AF2_HA.csv” file from population 2 (sp2) and “AF6_HA.csv” file from population 3 (sp3).

In addition, the setting of RMySQL table structure for the input data is required as illustrated in Table 3 if different datasets are used for SNPs comparison. The input data (as seen in Table 1) contains information which is organized into eight fields, separated by columns in the csv file. The assigned primary key, “id” column, must be unique and not null. SNPer queries the SNPs comparison in the tables using RMySQL with SQL commands. Furthermore, SNPer is executed to compare the SNPs of three viral subpopulations ordered by the list of SNPs files as shown in Table 2. The SNPs comparison outputs from RMySQL are processed and written in the output files by SNPer.

Table 3. The required table structure of the input data for SNPer computational analysis based on MySQL.

| Field | Type | Null | Key | Default | Extra |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| id | int(5) | NO | PRI | NULL | |

| sample_id | char(20) | YES | NULL | ||

| sample_name | char(20) | YES | NULL | ||

| chr | char(100) | YES | NULL | ||

| position | int(20) | YES | NULL | ||

| score | int(20) | YES | NULL | ||

| variant_type | char(20) | YES | NULL | ||

| call_ | char(8) | YES | NULL | ||

| frequency | int(5) | YES | NULL | ||

| depth | int(10) | YES | NULL | ||

| filter | char(20) | YES | NULL |

The table structure of the input data in the SNPer database can be retrieved by sql command (DESCRIBE <table_name>).

Expected Output Data for SNPs comparison

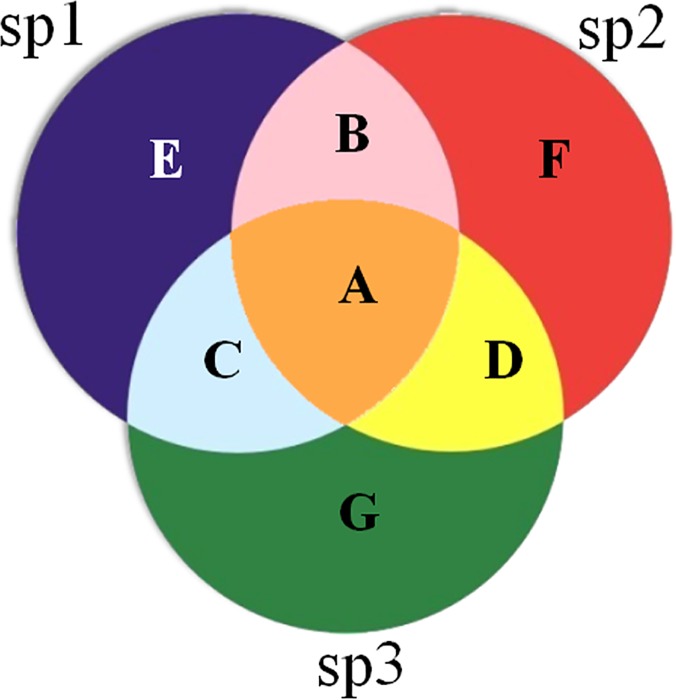

SNPer analyzes the output variants data from NGS done by the MiSeq Illumina platform and groups the SNPs of three different IFV subpopulations into (1) universal SNPs (shared in all viral subpopulations), (2) likely common SNPs (shared in almost all viral subpopulations), and (3) unique SNPs (not shared by other viral subpopulations). Fig 3 shows an example of SNPs comparison of three different viral subpopulations of influenza A/H3N2: viral subpopulation 1 (sp1), viral subpopulation 2 (sp2) and viral subpopulation 3 (sp3). Universal SNPs are located in area A. Likely common SNPs are presented in area B (in sp1 and sp2 but not in sp3), area C (in sp1 and sp3 but not in sp2) and area D (in sp2 and sp3 but not in sp1). Unique SNPs are indicated in area E (only in sp1), area F (only in sp2) and area G (only in sp3).

Fig 3. Comparison of SNPs from three different IFV subpopulations.

Area A contains universal SNPs. Areas B, C and D consist of likely common SNPs. Areas E, F and G contain unique SNPs.

Results

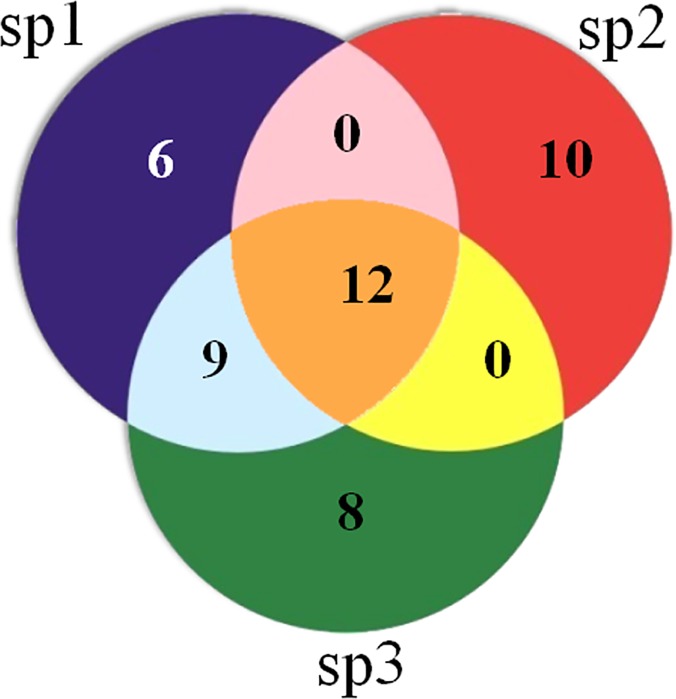

SNPer took three seconds to compare the SNPs of the complete eight IFV genomic fragments against three viral subpopulations as shown in Table 4. Each row displays distinct groups of SNPs [unique (only_spX), likely common (only_spX_spY), and universal SNPs (all)]. The HA fragment has the highest number of universal SNPs (all = 12) and unique SNPs (only_X = 6 + 10 + 8 = 24) as visualized in Fig 4. The comparison results from SNPer were checked by adding groups of SNPs according to the formula; no errors were found using SNPer. The summation of the SNPs of all groups from SNPer was equal to the summation of the total SNPs numbers in the fragments of the three subpopulations.

Table 4. The outputs of SNPer for the eight fragments of the three different IFVs (“summary.csv”).

| samples_table | sp1 | sp2 | sp3 | all | only_sp1 | only_sp2 | only_sp3 | only_sp1_sp2 | only_sp2_sp3 | only_sp3_sp1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AF1_HA_vs_AF2_HA_vs_AF6_HA | 27 | 22 | 29 | 12 | 6 | 10 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| AF1_M_vs_AF2_M_vs_AF6_M | 8 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| AF1_NA_vs_AF2_NA_vs_AF6_NA | 13 | 12 | 16 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| AF1_NEP_vs_AF2_NEP_vs_AF6_NEP | 5 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| AF1_NP_vs_AF2_NP_vs_AF6_NP | 11 | 9 | 10 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| AF1_PA_vs_AF2_PA_vs_AF6_PA | 15 | 8 | 18 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 9 |

| AF1_PB1_vs_AF2_PB1_vs_AF6_PB1 | 18 | 21 | 21 | 9 | 3 | 11 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| AF1_PB2_vs_AF2_PB2_vs_AF6_PB2 | 31 | 16 | 26 | 11 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

Each row shows the number of SNPs of VIROAF1 (sp1), VIROAF2 (sp2) and VIROAF6 (sp3) for each fragment after comparison by SNPer. For example, in the first row, the HA fragment contains 27 SNPs in VIROAF1, 22 SNPs in VIROAF2 and 29 SNPs in VIROAF6. Twelve universal SNPs are in VIROAF1, VIROAF2, and VIROAF6. There are six SNPs in only VIROAF1, 10 SNPs in only VIROAF2 and eight SNPs in only VIROAF6. Only nine SNPs exist in both VIROAF6 and VIROAF1.(1)

Fig 4. The SNPs composition output chart of three HA sequences from three IFV subpopulations.

Each circle represents the number of SNPs of VIROAF1 (sp1), VIROAF2 (sp2) and VIROAF6 (sp3) for the HA fragment; universal SNPs; unique SNPs; and likely common SNPs.

| (1) |

only_spX: number of SNPs only detected in the X subpopulation.

only_spX_spY: number of SNPs shared between the X and Y but not Z subpopulation.

all: number of SNPs shared by all subpopulations (X, Y and Z).

For example, the results from SNPer for the HA fragment of viral subpopulations VIROAF1, VIROAF2, and VIROAF6 were validated with the number of SNPs from Table 3. The summation of the number of SNPs in the HA fragment of the three subpopulations is 78 (27+22+29). The summation of SNPs from each group for the HA fragment of the three subpopulations is 78 [6+10+8+(0+0+9)*2+(12*3)]. Therefore, SNPer correctly produced the outputs of the HA fragment of the three subpopulations.

The complete list of SNPs for each group is provided in an output folder. An example of the list is shown in Table 5. The position and call (e.g., A405G) illustrates the universal SNPs from the three subpopulations.

Table 5. The allelic list of the universal SNPs found in HA fragment (“AF1_HA_vs_AF2_HA_vs_AF3_HA_sim_all.csv”).

| id | sample_id | sample_name | id | sample_id | sample_name | id | sample_id | sample_name | position | call_ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | 5 | VIROAF2 | VIROAF2 | 6 | VIROAF6 | VIROAF6 | 405 | A->[G/G] |

| 9 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | 6 | VIROAF2 | VIROAF2 | 7 | VIROAF6 | VIROAF6 | 413 | G->[A/A] |

| 11 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | 9 | VIROAF2 | VIROAF2 | 11 | VIROAF6 | VIROAF6 | 482 | A->[G/G] |

| 13 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | 10 | VIROAF2 | VIROAF2 | 14 | VIROAF6 | VIROAF6 | 629 | C->[T/T] |

| 14 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | 11 | VIROAF2 | VIROAF2 | 15 | VIROAF6 | VIROAF6 | 640 | G->[T/T] |

| 17 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | 13 | VIROAF2 | VIROAF2 | 16 | VIROAF6 | VIROAF6 | 715 | G->[A/A] |

| 19 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | 16 | VIROAF2 | VIROAF2 | 21 | VIROAF6 | VIROAF6 | 973 | A->[G/G] |

| 21 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | 17 | VIROAF2 | VIROAF2 | 22 | VIROAF6 | VIROAF6 | 1195 | A->[C/C] |

| 23 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | 18 | VIROAF2 | VIROAF2 | 25 | VIROAF6 | VIROAF6 | 1323 | A->[G/G] |

| 24 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | 19 | VIROAF2 | VIROAF2 | 26 | VIROAF6 | VIROAF6 | 1341 | T->[G/G] |

| 26 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | 21 | VIROAF2 | VIROAF2 | 28 | VIROAF6 | VIROAF6 | 1606 | C->[T/T] |

| 27 | VIROAF1 | VIROAF1 | 22 | VIROAF2 | VIROAF2 | 29 | VIROAF6 | VIROAF6 | 1671 | A->[G/G] |

Twelve universal SNPs detected among three subpopulations in HA fragment are A405G, G413A, A482G, C629T, G640T, G715A, A973G, A1195C, A1323G, C1606T, A1671G when compared to the influenza A/H3N2 reference (GenBank CY121792). Each row displays each SNP position.

Discussion and Conclusion

The SNPer library utilizes RMySQL to compare IFV SNPs stored in MySQL. SNPer was efficiently executed on Linux and Microsoft Windows operating systems. In addition, manual visualization utilizing the same set of SNPs data by qualified performers under non-distracting conditions generally required more than 40 hours (data not shown).

Although similar software packages already exist, SNPer has certain advantages compared to currently available package tools. For instance, VCFtools [16] can compare two subpopulations (two files) whereas SNPer can compare three subpopulations. Although the VCFtools user can merge the SNPs data of two subpopulations to compare with a third subpopulation, it is a cumbersome and time-consuming process, especially when running many subpopulation fragments. A second software package, VariantToolChest [17], requires reference genomes in fasta format, and is time and memory consuming. In contrast, SNPer does not need any reference genome during comparison and takes less time and memory when compared to VariantToolsChest. Moreover, the VariantToolsChest user needs to create many different sets of commands to compare the fragments from three subpopulations. For example, to compare the SNPs of eight gene fragments from three subpopulations, VariantToolsChest requires 56 different commands, while SNPer requires one command. Therefore, SNPer is more efficient than VariantToolsChest, especially during analysis of multiple genomic fragments. In addition, users validate the outcome from VariantToolsChest and VCFtools whereas sql commands automatically validate outcomes from SNPer. In terms of running time and the resources needed to analyze our test dataset, SNPer requires the least, followed by VCFtools and VariantToolsChest.

In conclusion, SNPer is a rapid and efficient tool to detect SNPs to monitor IFV evolution. This efficiency only increases with higher numbers of SNPs. SNPer could be used to analyze quantitative variants of SNPs among not only IFV subpopulations [12] but also other pathogens such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). SNPer has the potential to improve our ability to understand evolving populations of viruses and other pathogens, particularly for identifying novel universal SNPs associated with specific traits (e.g., drug resistance, virulence, etc.) which can emerge under selective pressure. This tool could allow for more timely response to these newly emerging pathogens.

Software Availability

The SNPer package and its manual are available at http://www.mbb.psu.ac.th/SNPer/index.html

Acknowledgments

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the US Government. We are grateful to Prof. Dr. Amornrat Phongdara and Assoc. Prof. Dr. Wilaiwan Chotigeat for their support for the Prince of Songkla University (PSU) research group in bioinformatics, Ms. Angkana Huang from the Department of Virology, Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences for her helpful comments on the manuscript. We also thank the National e-Science Infrastructure Consortium, Thailand, for supporting computing infrastructure to develop the SNPer library.

Data Availability

The SNPer package and its manual are available at http://www.mbb.psu.ac.th/SNPer/index.html

Funding Statement

This work was funded by Thailand Center of Excellence for Life Sciences (TCELS). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Zhirnov OP, Vorobjeva IV, Saphonova OA, Poyarkov SV, Ovcharenko AV, Anhlan D, et al. Structural and evolutionary characteristics of HA, NA, NS and M genes of clinical influenza A/H3N2 viruses passaged in human and canine cells. J Clin Virol. 2009. Aug;45(4):322–33. 10.1016/j.jcv.2009.05.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Webster RG, Bean WJ, Gorman OT, Chambers TM, Kawaoka Y. Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Microbiol Rev. 1992. Mar;56(1):152–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Grada A, Weinbrecht K. Next-generation sequencing: methodology and application. J Invest Dermatol. 2013. Aug;133(8):e11 10.1038/jid.2013.248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Barzon L, Lavezzo E, Militello V, Toppo S, Palu G. Applications of next-generation sequencing technologies to diagnostic virology. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12(11):7861–84. 10.3390/ijms12117861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ihaka R, Gentleman R. R: A language for data analysis and graphics. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 1996;5(3):299–314. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reimers M, Carey VJ. Bioconductor: an open source framework for bioinformatics and computational biology. Methods Enzymol. 2006;411:119–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Aulchenko YS, Ripke S, Isaacs A, van Duijn CM. GenABEL: an R library for genome-wide association analysis. Bioinformatics. 2007. May 15;23(10):1294–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sangket U, Mahasirimongkol S, Chantratita W, Tandayya P, Aulchenko YS. ParallABEL: an R library for generalized parallelization of genome-wide association studies. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:217 10.1186/1471-2105-11-217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schaefer C, Meier A, Rost B, Bromberg Y. SNPdbe: constructing an nsSNP functional impacts database. Bioinformatics. 2012. Feb 15;28(4):601–2. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schwarz DF, Hadicke O, Erdmann J, Ziegler A, Bayer D, Moller S. SNPtoGO: characterizing SNPs by enriched GO terms. Bioinformatics. 2008. Jan 1;24(1):146–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rutvisuttinunt W, Chinnawirotpisan P, Simasathien S, Shrestha SK, Yoon IK, Klungthong C, et al. Simultaneous and complete genome sequencing of influenza A and B with high coverage by Illumina MiSeq Platform. J Virol Methods. 2013. Nov;193(2):394–404. 10.1016/j.jviromet.2013.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rutvisuttinunt W, Chinnawirotpisan P, Thaisomboonsuk B, Rodpradit P, Ajariyakhajorn C, Manasatienkij W, et al. Viral subpopulation diversity in influenza virus isolates compared to clinical specimens. Journal of Clinical Virology (In press). 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13. Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009. Jul 15;25(14):1754–60. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. DePristo MA, Banks E, Poplin R, Garimella KV, Maguire JR, Hartl C, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011. May;43(5):491–8. 10.1038/ng.806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010. Sep;20(9):1297–303. 10.1101/gr.107524.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Danecek P, Auton A, Abecasis G, Albers CA, Banks E, DePristo MA, et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics. 2011. Aug 1;27(15):2156–8. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ebbert MT, Wadsworth ME, Boehme KL, Hoyt KL, Sharp AR, O'Fallon BD, et al. Variant Tool Chest: an improved tool to analyze and manipulate variant call format (VCF) files. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15 Suppl 7:S12 10.1186/1471-2105-15-S7-S12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The SNPer package and its manual are available at http://www.mbb.psu.ac.th/SNPer/index.html