Abstract

A migrating cell must establish front-to-back polarity in order to move. In this issue, Juanes-Garcia et al. (2015. J. Cell Biol. http://dx.doi.org/10.1083/jcb.201407059) report that a short serine-rich motif in nonmuscle myosin IIB is required to establish the cell’s rear. This motif represents a new paradigm for what determines directional cell migration.

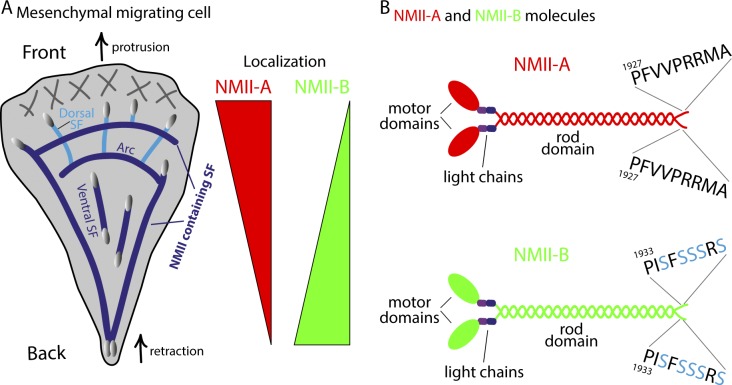

Directed cell movement is instrumental for organismal development, immune responses, and the progression of diseases, such as cancer (Gardel et al., 2010). To achieve directed movement, an individual cell must establish front-to-back polarity, where there is coordinated protrusion of its front and retraction of its back (Fig. 1 A; Vicente-Manzanares et al., 2007). How polymerizing actin filaments drive protrusion of the front is understood in exquisite detail (Pollard and Borisy, 2003; Pollard, 2007). The mechanisms defining how actin filament contraction defines the back of the cell (Yam et al., 2007) have been more difficult to elucidate. Contraction of actin filaments in crawling cells is driven by nonmuscle myosin II (NMII; Vicente-Manzanares et al., 2009). NMII has three isoforms, NMII-A, NMII-B, and NMII-C, all of which can bind and contract actin filaments to generate force. Importantly, NMII-A and NMII-B have different cellular localizations, which could drive their functions (Kolega, 1998; Vicente-Manzanares et al., 2007). NMII-A localizes primarily to the front, protrusive edge and is required for adhesion maturation. In contrast, NMII-B localizes behind NMII-A, primarily to large and stable actin stress fibers in the middle and back of the cell (Kolega, 1998; Vicente-Manzanares et al., 2007). NMII-B is required for front-to-back polarity, as cells lacking NMII-B lose large stress fibers and fail to define their rear (Vicente-Manzanares et al., 2007). The major question of what drives the polarized localization of NMII-B is unknown. In this issue, Juanes-Garcia et al. report that a short serine-rich motif in NMII-B is responsible for both its localization and the establishment of front-to-back cellular polarity.

Figure 1.

Nonmuscle myosins in cell migration. (A) Schematic showing a top view of a crawling cell. The front of the cell is protruding (top arrow), and the back of the cell is retracting (bottom arrow). The protrusion of the edge is driven by polymerization of actin filament networks in the lamellipodium (gray hash marks). NMII-containing stress fibers (SF, dark blue lines) are assembled behind the lamellipodium. SFs are connected to focal adhesions (gray ovals) either directly or indirectly through non-NMII–containing actin bundles (Dorsal SF, light blue lines; Naumanen et al., 2008). Moving away from the cell’s front, there is a decreasing and increasing gradient of NMII-A (red wedge) and NMII-B (green wedge), respectively (Kolega, 1998). (B) Schematic of NMII-A and NMII-B isoforms. A single NMII molecule is a hexamer of two heavy chains (i.e., NMII-A, NMII-B, or NMIIC), two regulatory light chains, and two essential light chains (Vicente-Manzanares et al., 2009). The overall structure of NMII-A and NMII-B molecules is similar, with two motor domains, a coiled-coil rod domain, and a short nonhelical tail domain. The serine-rich motif is unique to NMII-B, and the role for this motif in SF contraction and the ability of the cell to apply forces to its environment are yet to be determined.

Though NMII-A and NMII-B are genetically and structurally very similar, Juanes-Garcia et al. (2015) identified a serine-rich sequence (SFSSSRS) in the C terminus of NMII-B (Fig. 1 B). The authors effectively used cells depleted of NMII-B (Vicente-Manzanares et al., 2007) to test the role of this serine motif in front-to-back polarity. Although expression of wild-type NMII-B rescued front-to-back polarity, expressing NMII-B lacking the serine motif did not. Interestingly, simply inserting the serine-rich motif from NMII-B into NMII-A (NMII-A5S) conferred the ability to rescue front-to-back polarity. In addition, NMII-A5S did not localize to the front of the cell or play a role in adhesion maturation like wild-type NMII-A. Mass spectrometry analysis revealed three of the residues in the serine motif of NMII-B were phosphorylated in cells, and one of these, serine 1935, was found to be crucial for the wild-type kinetics and localization of NMII-B. A phosphomimetic point mutation, S1935D, failed to rescue front-to-back polarity in NMII-B–depleted cells. In contrast, expression of the nonphosphorylatable mutant, S1935A, localized normally to large actin stress fibers and did rescue front-to-back polarity.

To provide further evidence that serine 1935 is a regulatory element of front-to-back polarity, Juanes-Garcia et al. (2015) investigated the role of PKC, which acts upstream of NMII in cell polarization (Gomes et al., 2005; Even-Faitelson and Ravid, 2006), in NMII-B–generated stable actin bundles. Cells expressing constitutively active PKC produced isotropic protrusions at the perimeter of the cell, while also failing to produce large, stable NMII-B decorated actin bundles. This isotropic protrusive phenotype was blocked when nonphosphorylatable NMII-B S1935A was expressed in cells but not with wild type or S1935D. Thus, PKC was implicated as the likely upstream regulator of NMII-B activity, which negatively regulates stable actin stress fiber formation by phosphorylating NMII-B at serine 1935. Taken together, the data presented strongly suggest that a small regulatory motif on NMII-B controls cellular front-to-back polarity in migrating cells.

The findings presented in this issue by Juanes-Garcia et al. (2015) shine a bright spotlight on a family of motors that has already taken “center stage” in cellular research (Vicente-Manzanares et al., 2009). Some exciting new questions as to how NMII-B functions in the establishment of asymmetric cellular shape and function can now be addressed, including but clearly not limited to: How does the unique enzymatic activity of NMII-B’s motor domain synergize with the serine motif to drive front-to-back polarity (Billington et al., 2013)? What are the structural and dynamic implications for homo- and/or hetero-NMII filament formation (Ricketson et al., 2010; Beach et al., 2014; Shutova et al., 2014)? Does the NMII-B serine motif play a role in the establishment of more complex 3D cellular shapes? Is the serine motif required for directional cell migration through physiological environments?

References

- Beach J.R., Shao L., Remmert K., Li D., Betzig E., and Hammer J.A. III. 2014. Nonmuscle myosin II isoforms coassemble in living cells. Curr. Biol. 24:1160–1166 10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billington N., Wang A., Mao J., Adelstein R.S., and Sellers J.R.. 2013. Characterization of three full-length human nonmuscle myosin II paralogs. J. Biol. Chem. 288:33398–33410 10.1074/jbc.M113.499848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Even-Faitelson L., and Ravid S.. 2006. PAK1 and aPKCζ regulate myosin II-B phosphorylation: a novel signaling pathway regulating filament assembly. Mol. Biol. Cell. 17:2869–2881 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardel M.L., Schneider I.C., Aratyn-Schaus Y., and Waterman C.M.. 2010. Mechanical integration of actin and adhesion dynamics in cell migration. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 26:315–333 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.011209.122036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes E.R., Jani S., and Gundersen G.G.. 2005. Nuclear movement regulated by Cdc42, MRCK, myosin, and actin flow establishes MTOC polarization in migrating cells. Cell. 121:451–463 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juanes-Garcia A., Chapman J.R., Aguilar-Cuenca R., Delgado-Arevalo C., Hodges J., Whitmore L.A., Shabanowitz J., Hunt D.F., Horwitz A.R., and Vicente-Manzanares M.. 2015. A regulatory motif in nonmuscle myosin II-B regulates its role in migratory front–back polarity. J. Cell Biol. 10.1083/jcb.201407059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolega J.1998. Cytoplasmic dynamics of myosin IIA and IIB: spatial ‘sorting’ of isoforms in locomoting cells. J. Cell Sci. 111:2085–2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naumanen P., Lappalainen P., and Hotulainen P.. 2008. Mechanisms of actin stress fibre assembly. J. Microsc. 231:446–454 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2008.02057.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard T.D.2007. Regulation of actin filament assembly by Arp2/3 complex and formins. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 36:451–477 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.101936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard T.D., and Borisy G.G.. 2003. Cellular motility driven by assembly and disassembly of actin filaments. Cell. 112:453–465 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00120-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricketson D., Johnston C.A., and Prehoda K.E.. 2010. Multiple tail domain interactions stabilize nonmuscle myosin II bipolar filaments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107:20964–20969 10.1073/pnas.1007025107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shutova M.S., Spessott W.A., Giraudo C.G., and Svitkina T.. 2014. Endogenous species of mammalian nonmuscle myosin IIA and IIB include activated monomers and heteropolymers. Curr. Biol. 24:1958–1968 10.1016/j.cub.2014.07.070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicente-Manzanares M., Zareno J., Whitmore L., Choi C.K., and Horwitz A.F.. 2007. Regulation of protrusion, adhesion dynamics, and polarity by myosins IIA and IIB in migrating cells. J. Cell Biol. 176:573–580 10.1083/jcb.200612043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicente-Manzanares M., Ma X., Adelstein R.S., and Horwitz A.R.. 2009. Non-muscle myosin II takes centre stage in cell adhesion and migration. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10:778–790 10.1038/nrm2786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yam P.T., Wilson C.A., Ji L., Hebert B., Barnhart E.L., Dye N.A., Wiseman P.W., Danuser G., and Theriot J.A.. 2007. Actin–myosin network reorganization breaks symmetry at the cell rear to spontaneously initiate polarized cell motility. J. Cell Biol. 178:1207–1221 10.1083/jcb.200706012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]