Abstract

Background

There are 60 000 to 100 000 new cases of borreliosis in Germany each year. This infectious disease most commonly affects the skin, joints, and nervous system. Lyme carditis is a rare manifestation with potentially lethal complications.

Methods

This review is based on selected publications on the clinical manifestations, diagnosis, and treatment of Lyme carditis, and on the authors’ scientific and clinical experience.

Results

Lyme carditis is seen in 4% to 10% of all patients with Lyme borreliosis. Whenever the clinical suspicion of Lyme carditis arises, an ECG is mandatory for the detection or exclusion of an atrioventricular conduction block. Patients with a PQ interval longer than 300 ms need continuous ECG monitoring. 90% of patients with Lyme carditis develop cardiac conduction abnormalities, and 60% develop signs of perimyocarditis. Borrelia serology (ELISA) may still be negative in the early phase of the condition, but is always positive in later phases. Cardiac MRI can be used to confirm the diagnosis and to monitor the patient’s subsequent course. The treatment of choice is with antibiotics, preferably ceftriaxone. The cardiac conduction disturbances are usually reversible, and the implantation of a permanent pacemaker is only exceptionally necessary. There is no clear evidence at present for an association between borreliosis and the later development of a dilated cardiomyopathy. When Lyme carditis is treated according to the current guidelines, its prognosis is highly favorable.

Conclusion

Lyme carditis is among the rarer manifestations of Lyme borreliosis but must nevertheless be considered prominently in differential diagnosis because of the potentially severe cardiac arrhythmias that it can cause.

Lyme borreliosis (Lyme disease) is the most prevalent vector-borne infectious disease in Europe (1). Leisure behavior as well as the longer seasonal activity of ticks due to climate change have resulted in an increase in Borrelia-associated morbidity (2, 3).

While Lyme disease most frequently affects the skin, joints, and nervous system, Lyme carditis is one of the rarer organ manifestations (1). However, cases with cardiac involvement can be severe and, in contrast to other Borrelia-associated diseases, sporadic fatal outcomes have been reported (4, 5, e1). Therefore, the aim of this review is to create awareness of Lyme carditis, focusing on differential diagnostic considerations.

Methods

This review is based on a selective search of pertinent literature, guided by the authors’ scientific and clinical experiences. For the sub-aspect of Borreliosis-related mortality, a systematic search of PubMed was performed, including all publications until 2014 (target parameters were morbidity, mortality, clinical course, and prognosis).

Pathogen and prevalence

Borrelia species are Gram-negative bacteria, belonging to the Spirochete family. In 1982, the pathogen Borrelia burgdorferi was first isolated from ticks (6) and later from the skin, blood and cerebrospinal fluid of infected patients (7, 8). In the meantime, various human-pathogenic species, distinguished by genotyping, have been identified in Europe. The Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex comprises:

Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto

Borrelia afzelii

Borrelia garinii

Borrelia spielmanii.

By contrast, in North America Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto is the only genospecies which has been implicated in Lyme disease (9).

Approximately 60 000 to 100 000 new cases of borreliosis are annually recorded in Germany (1, 3). The prevalence of Lyme carditis is 0.3 to 4% in Europe and 1.5 to 10% in the U.S. of all adult untreated patients with Lyme disease (10– 12). This variance in disease prevalence may be due to differences in the virulence of European and North American isolates. However, mammalian model-based histopathology studies suggest that the actual rate of cardiac involvement may be much higher (e2). A study on pediatric patients with Lyme disease found ECG changes indicative of myocardial involvement in approximately 30% of patients (13).

Transmission and course of the disease

Lyme disease is spread through the bite of the Ixodes ricinus tick (castor bean tick). Depending on the location, the average prevalence is in the range of 16 to 35% (3, 14). Once the tick has started to suck blood, the Lyme disease agent moves from the tick’s gut into its hemolymph and ultimately invades its salivary gland. With the tick’s saliva, the Borrelia bacteria are then transmitted to the host. As this process takes 12–24 hours to complete, timely removal of the tick can prevent the transmission of Borrelia (1, 2).

Once the pathogens have been transferred into the human organism, the disease develops in three stages:

Stage I: In stage I (days to weeks after the tick bite) , the most common presentation of the disease is the characteristic erythema chronicum migrans (Figure 1), along with unspecific signs and symptoms of infection, such as headache and muscle pain, fever, and swollen lymph nodes (1, 2).

Figure 1.

Erythema chronicum migrans on lower arm as an early manifestation of Lyme disease— erythematous ring expanding peripherally

Stage II: Weeks later, in the subsequent stage II (disseminated phase) of the disease, hematogenous spread and the typical organotropism of Borrelia result in the preferential involvement of specific organ systems. At this stage, the patient develops the classical organ manifestations, such as joint pain, neurological complications ([15], e.g., meningoradiculitis, facial palsy, encephalitis), Borrelia lymphocytoma, or Lyme carditis (1).

Stage III: Stage III (chronic phase/late persistent disease), occurring after two to three years, is characterized by the manifestations of chronic borreliosis, including chronic destructive arthritis and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (1, 2).

The clinical manifestations of Lyme carditis

Even though it is not uncommon for cardiac involvement of Lyme disease to be asymptomatic (2, 13, e2), clinical signs of Lyme carditis can be observed in patients following the manifestation of the erythema chronicum migrans rash (Fgure 1), after 21 days on average (11, 16). While generally no gender difference in the prevalence of Lyme disease is found, Lyme carditis more commonly affects men (ratio 3 : 1) (11, 12). Steere et al. (11) described for the first time in 1980 a case series of 20 patients who developed Lyme carditis. In addition to exertional dyspnea, chest pain or irregular heartbeat, typical symptoms include episodes of syncope. On physical examination, 35% of patients presented with bradycardia and approx. 15% with tachycardia (11).

Some patients report concomitant symptoms of other Borrelia-associated organ manifestations, such as joint ache or neurological symptoms associated with meningoencephalitis (11). The criteria used to diagnose Lyme carditis are summarized in the Box.

Box. Diagnostic criteria for Lyme carditis (modified according to [17]).

-

Clinical picture

Newly developed AV conduction disorder (especially in young patients) or other arrhythmia. Signs and symptoms of perimyocarditis. Additional history of existing/previous erythema chronicum migrans (ECM) or tick bite. Exclusion of other differential diagnoses

-

Laboratory testing

Detection of specific antibodies (Borrelia burgdorferi) in serumLimitation: Positive serology alone is not sufficient to diagnose Lyme carditis!

-

Special testing (individual cases)

Detection of Borrelia DNA in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (myocardial biopsy specimen)

Diagnosis

If cardiac involvement of Lyme disease is suspected, pertinent basic investigations should be initiated (18), including:

Laboratory testing

12-channel ECG and 24-hour Holter ECG (query: rhythm analysis, PQ interval, QRS width, ectopic beats)

Chest radiograph (query: heart size, congestion)

Echocardiography (diameter, ejection fraction, wall motion abnormality, pericardial effusion).

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (19, 20, e3, e4), myocardial biopsy (21, 22) or electrophysiological examination (23, 24) may provide valuable insights in individual cases, helping to confirm the diagnosis and establish a prognosis.

Laboratory testing

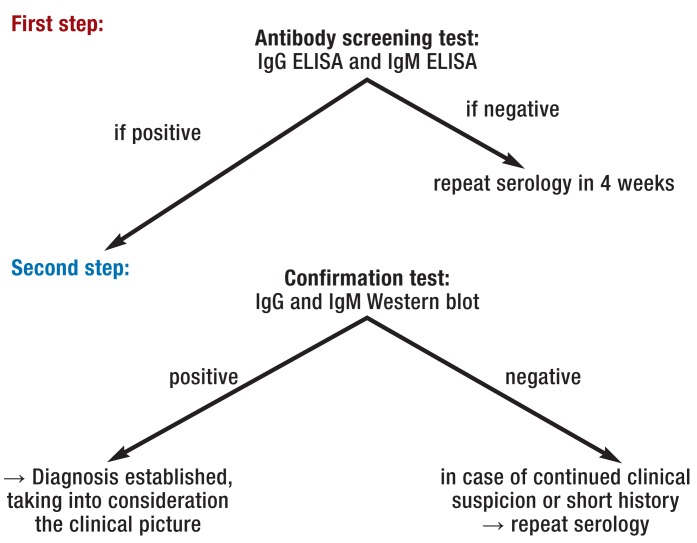

Today, a variety of Borrelia laboratory tests are available. However, because of the high antigen variability of Borrelia, significant differences between regional Borrelia strains and the lack of standardization of test methods with ultimately limited sensitivities and specificities of conventional test kits, serological results should always be interpreted in the context of the patient’s clinical condition or course of the disease. Today’s two-step testing procedure (Figure 2) uses a sensitive enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as an IgM and IgG antibody screening test; then, positive or borderline results are confirmed using a Western blot assay (1).

Figure 2.

First step:

Two-tiered antibody testing for Lyme disease

Due to the often delayed immune response, results may be false negative in the early stage of the disease. There is, for example, an early diagnostic gap in 50% of patients with erythema migrans. Consequently, negative serology does not rule out early infection. In contrast, in late-stage Lyme disease elevated IgG levels are almost always present. This means that seronegative late-stage infection is non-existent (9).

Other often newer methods, such as the lymphocyte transformation test, Borrelia antigen test in urine, Borrelia spheroblast formation, or visual contrast sensitivity testing, cannot be recommended at present due to their low sensitivity and lack of replicability and standardization (1, 9).

Histopathology

Endomyocardial biopsy is considered the gold standard for diagnosing myocarditis and continues to play an important role, especially in complicated cases, presenting with e.g. heart failure, left ventricular dilatation or higher-degree arrhythmias (21, 25).

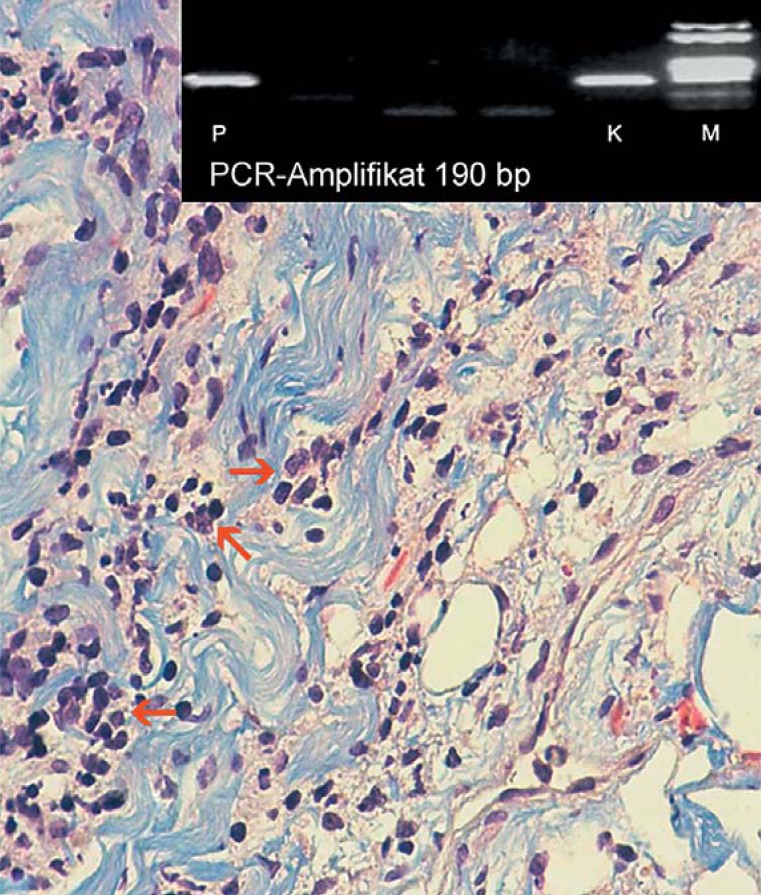

In Lyme carditis, histological processing of myocardial biopsy specimens shows transmural inflammatory infiltrates with characteristic band-like endocardial lymphocytic infiltration (Figure 3) (10, 21, 26). Occasionally, spirochetes can be identified next to or within these infiltrates, between muscle fibers or within the endocardium (23, 27). Histopathologically, the inflammatory reaction induced by the spirochete infection is discussed as a possible mechanism underlying the cardiac organ damage, besides a direct destructive effect of the spirochetes. In addition, the discrepancy between only sporadically identified spirochetes and the extent of lymphocytic infiltration (Figure 3) suggests an immunological component to the etiology of Lyme carditis (10, 22, e5).

Figure 3.

Histology of endomyocardial biopsy from a patient with Lyme carditis: Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) band pattern (top insert in the image) with patient specimen (P) on the left. Identification of Borrelia burgdorferi DNA (ospA gene region, PCR amplificate of 190 bp as a bright band), control (K) on the right with corresponding band on the same height, and size standard (M) on the far right. Histopathological appearance of lymphocytic myocarditis (red arrows) with significant subendocardial fibrosis (stained blue) and pathogen persistence correspond to stage II of Lyme disease (Masson’s trichrome stain, x 400)

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay for the detection of Borrelia burgdorferi DNA in endomyocardial biopsy specimens can help to establish the diagnosis of Lyme carditis (e6), as shown in Figure 3. However, to ensure reliable specificity the biopsy material must be carefully obtained and the test must be performed in a highly specialized laboratory. As with PCR assays from synovial or cerebrospinal fluid specimens, Lyme carditis is not ruled out by a negative myocardial biopsy PCR result (1, 9, e7).

ECG changes and electrophysiological findings

As with viral myocarditis, changes in surface ECG are a common finding in Lyme carditis. Diffuse myocardial involvement frequently results in ST segment changes. According to the largest published study of Steere et al. (11), 60% of the patients showed ST segment depression or T wave inversion, especially in the inferolateral leads. With clinical remission, these changes disappeared completely. Even more common than these unspecific repolarization abnormalities are AV conduction disorders that can be observed in the 12-channel ECG and 24-hour Holter ECG.

In the case series of Steere et al., 90% of all patients with Lyme carditis presented with a first-degree AV block and at least 44% of these patients experienced, at least temporarily, a complete AV block. Mc Alister (16) described in his analysis of more than 52 published cases of Lyme carditis an AV block in 87% and 53% of the patients had a complete AV block or Mobitz-type block. Likewise, van der Linde (12) reported in his retrospective analysis of 105 cases in 49% of patients a third-degree AV block and in 16% a second-degree block. It is not uncommon that the location of the AV conduction disorder fluctuates from a first-degree block to a His-Purkinje block within a few minutes. According to Steere et al. (11), a progression of a first-degree AV block to a complete AV block was highly likely, when the PQ interval was above 300 msec. Although Lyme carditis can essentially occur in any decade of life, Lyme disease should be considered as a differential diagnosis especially in young patients with unclear AV block.

Electrophysiological data related to Lyme carditis are only available from case reports. Here, a mainly supra-Hisian/intranodular AV block with corresponding abnormalities of the AH intervals (interval between atrial depolarization and His bundle) and a small-based AV junctional escape rhythm was identified. Apart from this constellation, which bears a good prognosis, only sporadic reports of infra-Hisian blocks with prolonged HV interval (interval between His bundle and ventricle) have been documented (16, 24, e8). Likewise, cases of sinus node dysfunction, more precisely of sinoatrial blocks (13, 16, e9), temporary bundle blocks (16), and paroxysmal atrial fibrillations (11) have been described. In three children with Lyme carditis, a prolonged QT interval was reported (28).

Diagnostic imaging

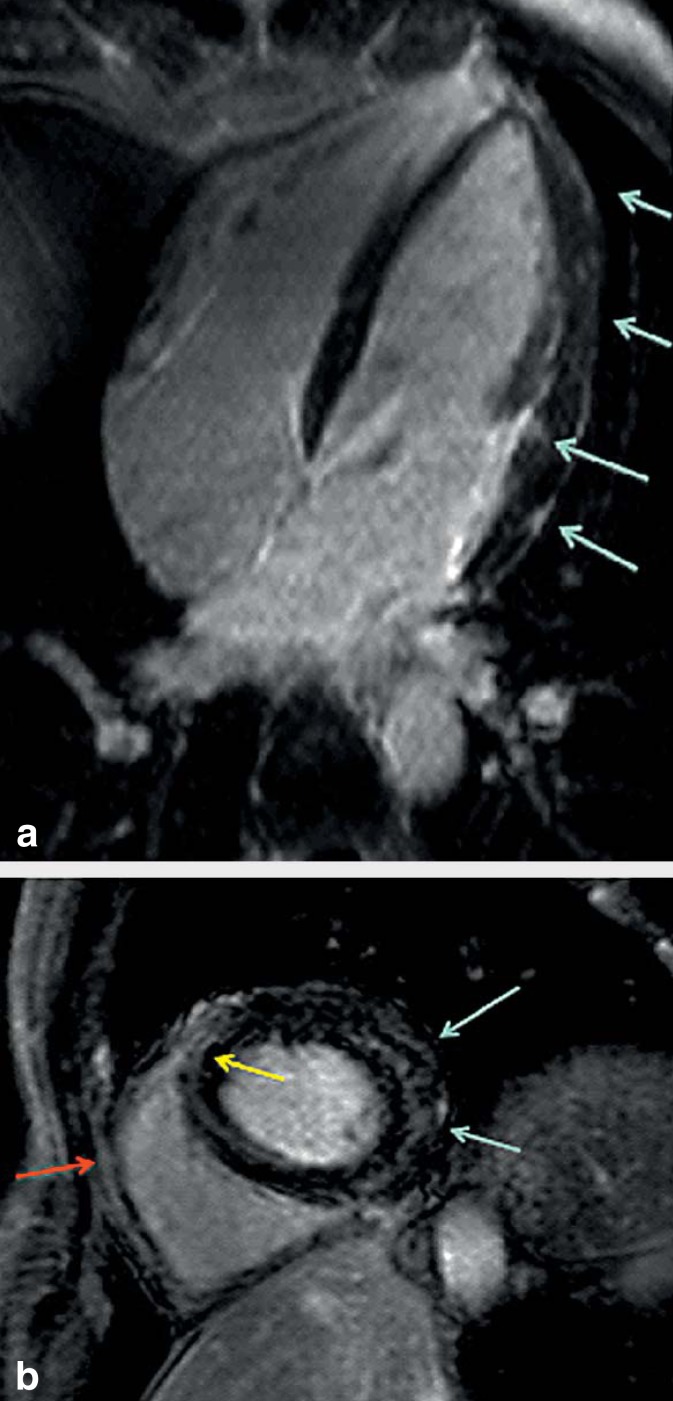

Both echocardiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cardiac MRI) can provide valuable information about pericardial involvement, which may manifest, for example, as pericardial effusion. Left ventricular dysfunction with detection of abnormalities of left ventricular kinetics may be indicative of myocarditis. On cardiac MRI, a wall edema can present with increased signal intensity on T1-weighted images, corresponding to myocardial inflammatory processes triggered by the spirochetes. After gadolinium administration, intramyocardial or epicardial signal enhancement is observed with late-enhancement imaging (LE) (Figure 4) (19). The possible increase in pericardial signal intensity results from pericarditis-induced irritation (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging with 4-chamber view

a) of a patient with Lyme carditis along with first-degree AV block and complete left bundle-branch block: after gadolinium administration, multilocular late-enhancement (LE), situated subepicardially, mid-myocardially and subendocardially.

b) In the short-axis view, LE is primarily situated in the mid-myocardium; however, the septum is also affected, possibly the substrate of the affected conduction system (yellow arrow). In addition, slight enhancement of the pericardium (red arrow)

Furthermore, MRI can be used to monitor left ventricular dysfunction and the perimyocardial inflammatory process (19, 20, e3, e4, e10).

Chronic course

Isolation of Borrelia burgdorferi from the myocardial biopsy specimen of a patient with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) by Stanek and Bergler-Klein (27) suggested that the heart condition and the spirochete infection were linked. While the same work group (29) demonstrated an increased prevalence of Borrelia antibodies in patients with DCM, this correlation could not be confirmed in later studies by Levolas (30) and Rees (e11). The latest studies (22, 31), using a highly sensitive PCR method, found a significantly higher genome prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi in patients recently diagnosed with DCM as compared with controls (in [22]: in 24% Borrelia genome detectable in myocardial biopsy specimens versus 0% in the control group). While Palacek et al. (31) observed a significant improvement of left ventricular function under antibiotic treatment in their patient population which tested positive for Borrelia genome, Kubanek et al. (22) found no positive response to this therapy.

In conclusion, there are no dependable epidemiological data available that prove the existence of a link between Borrelia infection and the development of DCM.

Therapeutic aspects

Lyme carditis has an overall good prognosis, as have other forms of Lyme disease (14).

Patients with a strong clinical suspicion of Lyme disease along with syncopal episodes or the presence of second- or third-degree atrioventricular block (Box) should be admitted to hospital for continuous monitoring of their heart rhythm (11, 32). Such an approach also applies to patients with Lyme disease, presenting with a PQ interval of >300 ms (11). The hospital must be equipped for temporary pacemaker implantation, because in approximately 35% patients with Lyme carditis the progression of the heart block will require temporary ventricular stimulation (12, 33). However, patients with high-degree AV block typically recover within one week (16, 34). Due to this high remission rate, rushing the implantation of a permanent pacemaker system is not recommended (18).

Taking into account the guidelines of the European Federation of Neurological Societies (15) on the diagnosis and management of Lyme neuroborreliosis, today ceftriaxone (alternative: cefotaxime), administered over a period of two weeks, has become the standard antibiotic for the treatment of acute Lyme carditis (1, 18). The aim of this early initiated antibiotic treatment is to rapidly eliminate the spirochetes. Even though the data currently available do not provide conclusive evidence of the effect of this antibiotic regimen on remission rate and remission time of the conduction disorder, this treatment approach is generally followed, in particular because of its positive impact on other organ manifestations of Lyme disease (1, 32).

In contrast, antibiotic treatment of a long-standing dilated cardiomyopathy based on the assumption of a past Borrelia infection cannot be recommended because of the inconsistency of the presently available data (22, 35, 31, 36, e11).

Prognosis

As with other organ manifestations of Lyme disease, Lyme carditis has a good prognosis in patients receiving treatment in keeping with what is recommended in the guidelines. Even though in approximately 60% of patients who develop a higher-degree AV block temporary pacemaker implantation is required (16), patients with high-degree infra-Hisian block usually recover within one week, with first-degree conduction disorder within six weeks (16, 34). Therefore, only in absolutely exceptional cases, the implantation of a permanent pacemaker is indicated (11, 30, e8).

A systematic analysis of the literature on Lyme disease mortality identified nine documented deaths worldwide (Table). In seven cases, sudden cardiac death occurred as a result of acute lymphocytic myocarditis. Retrospectively, a primary arrhythmogenic event—more precisely a higher-degree AV block—has to be discussed as the immediate cause of death in these cases. In two cases (Table: Waniek et al. [37] and Kirsch et al. [e12]), secondary, non-cardiac complications after a course of Lyme disease over several months were responsible for the fatal outcome.

Table. Result of a systematic analysis of the literature on the mortality of Lyme disease*.

| Author | Publication | Number of deaths | Clinical information | Cause oWf death |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deresinski S | Case report, 2014, (38) |

3 | Patient age between 26 and 38 years (2 male, one female) Cardinal symptom: exertional dyspnea, chest pain and unspecific symptoms of infection Relevant secondary diagnoses: none |

Sudden cardiac death in acute lymphocytic myocarditis, identification of spirochetes in the myocardium, positive PCR (Borrelia burgdorferi DNA) |

| Tavora F et al. | Case report, 2008, (39) |

1 | 37-year-old man Cardinal symptom: fever, rash Secondary diagnoses: none |

Sudden cardiac death, diffuse lymphocytic myocarditis, positive Borrelia serology, positive PCR (Borrelia burgdorferi DNA), documented second-degree AV block |

| Waniek C et al. | Case report, 1995, (37) |

1 | 48-year-old man Cardinal symptom: progressive personality disorder Secondary diagnoses: none |

Rapidly progressive dementia, suspected neuroborreliosis, spirochetes identified in the thalamus |

| Reimers CD et al. | Case report, 1993, (e13) |

1 | 38-year-old man Admission diagnosis: Guillain-Barré syndrome Secondary diagnoses: none |

Sudden cardiac death in acute lymphocytic myocarditis, positive Borrelia serology, identification of spirochetes in skeletal muscles |

| Cary NR et al. | Case report, 1990, (4) |

1 | 31-year-old farmer Admission diagnosis: myositis, rash Secondary diagnoses: hepatitis of unknown origin, arterial hypertension |

Sudden cardiac death in acute lymphocytic myocarditis, third-degree AV block, positive Borrelia serology |

| Kirsch M et al. | Case report, 1988, (e12) |

1 | 67-year-old woman Cardinal symptoms: fever, rash Secondary diagnosis: arterial hypertension |

Prolonged course with ARDS, positive Borrelia serology |

| Marcus LC et al. | Case report, 1985, (5) |

1 | 66-year-old man Cardinal symptom: unspecific symptoms of infection Secondary diagnosis: babesiosis |

Sudden cardiac death in acute myocarditis, lymphocytic pancarditis with identification of spirochetes in the myocardium |

*All published deaths of Lyme disease in the PubMed database. Search period until end of 2014;

PCR = polymerase chain reaction; ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome (pulmonary failure)

Key Messages.

Lyme carditis occurs in 4 to 10% of all patients with Lyme disease. Typical clinical manifestations include perimyocarditis, but also conduction disorders (80 to 90% of patients).

The diagnostic triad of Lyme carditis comprises medical history (erythema migrans, tick bite), AV block in ECG and a positive Borrelia serology.

Where Lyme carditis is clinically suspected, continuous ECG monitoring is required in patients who have experienced a syncope or present with a PQ interval >300 ms. Further investigations include, in addition to Borrelia serology, echocardiography, cardiac MRI and, in individual cases, myocardial biopsy.

In by far the most cases, the conduction disorders are fully reversible within six weeks. Only in absolutely exceptional cases, the implantation of a permanent pacemaker is required.

Provided patients receive antibiotic treatment with ceftriaxone, the prognosis is excellent. A clear correlation between Lyme carditis and the development of chronic dilated cardiomyopathy cannot be established based on the currently available data

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ralf Thoene, MD.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Stanek G, Wormser GP, Gray J, Strle F. Lyme borreliosis. Lancet. 2012;379:461–473. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubrey SW, Bhatia A, Woodham S, Rakowicz W. Lyme disease in the United Kingdom. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:33–42. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frank C, Faber M, Hellenbrand W, Wilking H, Stark K. Wichtige, durch Vektoren übertragene Infektionskrankheiten beim Menschen in Deutschland. Epidemiologische Aspekte. Bundesgesundheitsbl. 2014;5:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00103-013-1925-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cary NR, Fox B, Wright DJM, Cutler SJ, Shapiro LM, Grace AA. Fatal lyme carditis and endodermal heterotopia of the atrioventricular node. Postgrad Med J. 1990;66:134–136. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.66.772.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcus LC, Steere AC, Duray PH, Anderson AE, Mahoney EB. Fatal pancarditis in a patient with coexistent lyme disease and babesiosis. Demonstration of spirochetes in the myocardium. Ann Intern Med. 1985;103:374–376. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-103-3-374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burgdorfer W, Barbour AG, Hayes SF, Beneach JL, Grunwaldt E, Davis JP. Lyme disease, a tick-borne spirochetosis. Science. 1982;216:1317–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.7043737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beneach JL, Bosler EM, Hanrahan JP. Spirochetes isolated from the blood of two patients with lyme-disease. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:740–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198303313081302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ciesielski CA, Markowitz LE, Horsley R, Hightower AW, Russell H, Broome CV. Lyme disease surveillance in the United States, 1983-1986. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11:1435–1441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stanek G, Reiter M. The expending lyme borrelia complex: clinical significance of genomic species ? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:487–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cox J, Krajden M. Cardiovascular manifestations of lyme disease. Am Heart J. 1991;122:1449–1455. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90589-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steere AC, Batsford WP, Weinberg M, et al. Lyme carditis: cardiac abnormalities of lyme disease. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93:8–16. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-93-1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Linde MR. Lyme-carditis: clinical characteristics of 105 cases. Scand J Infect Dis. 1991;77:81–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woolf PK, Lorsung EM, Edwards KS. Electrocardiographic findings in children with lyme disease. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1991;7:334–336. doi: 10.1097/00006565-199112000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nau R, Christen HJ, Eiffert H. Lyme disease—current state of knowledge. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009;106:72–82. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mygland A, Ljøstad U, Fingerle V, Rupprecht T, Schmutzhard E, Steiner I. EFNS guidelines on the diagnosis and management of European lyme neuroborreliosis. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:8–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mc Alister HF, Klementowicz C, Andrews JD, Fisher JD, Feld M, Furman S. Lyme carditis: an important cause of reversible heart block in lyme disease. Ann Intern Med. 1989;110:339–345. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-110-5-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stanek G, Fingerle V, Hunfeld KP, et al. Lyme borreliosis: Clinical case definitions for diagnosis and management in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:69–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scheffold N, Bergler-Klein J, Sucker C, Cyran J. Kardiovaskuläre Manifestationsformen der Lyme-Borreliose. Dtsch Artzebl. 2003;14:A 912–A 920. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hombach V, editor. Stuttgart, New York: Schattauer Verlag; 2009. Kardiovaskuläre Magnetresonanztomographie; pp. 149–152. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munk PS, Ors S, Larsen AI. Lyme carditis: persistent local delayed enhancement by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Cardiol. 2007;115:e108–e110. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.05.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kandolf R. Myokarditis-Diagnostik. Dtsch Med Wschr. 2011;136:829–835. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1275813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kubanek M, Sramko M, Berenova D, et al. Detection of borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in endomyocardial biopsy specimens in individuals with recent-onset dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:588–596. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Linde MR, Crijus HJ, de Koning J, et al. Range of atrioventricular conduction disturbances in lyme borreliosis: a report of four cases and review of other published reports. Br Heart J. 1990;63:162–168. doi: 10.1136/hrt.63.3.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Linde MR, Crijns HJ, Lie KI. Transient complete AV-block in lyme disease: electrophysiologic observations. Chest. 1989;96:219–221. doi: 10.1378/chest.96.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kühl U, Schultheiss HP. Myocarditis: early biopsy allows for tailored regenerative treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109:361–368. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Duray PH. Histopathology of clinical phases of human lyme disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1989;15:691–710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stanek G, Klein J, Bittner R, Glogar D. Isolation of borrelia burgdorferi from the myocardium of a patient with long-standing cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 1990;322:249–252. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199001253220407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seslar SP, Berul CI, Burklow TR, Cecchin F, Alexander ME. Transient prolonged corrected QT intervall in lyme disease. J Pediatr. 2006;148:692–697. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stanek G, Klein J, Bittner R, Glogar D. Borrelia burgdorferi as an etiologic agent in chronic heart failure. Scand J Infect Dis. 1991;77:85–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levolas P, Dontas I, Bassiakon E, Xanthos T. Cardiac implications of lyme disease, diagnosis and therapeutic approach. Int J Cardiol. 2008;129:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palecek T, Kuchynka P, Hulinska D, et al. Presence of borrelia burgdorferi in endomyocardial biopsies in patient with new onset unexplained dilated cardiomyopathy. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2010;199:139–143. doi: 10.1007/s00430-009-0141-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krause PJ, Bockenstedt LK. Lyme disease and the heart. Circulation. 2013;127:451–454. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.101485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lorincz I, Lakos A, Kovacs P. Temporary pacing in complete heart block due to lyme disease: a case report. PACE. 1989;12:1433–1436. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1989.tb05059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Allal J, Coisne D, Thomas P, et al. Manifestation cardiaques de la maladie de lyme. Ann Med Interne. 1986;137:372–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suedkamp M, Lissel C, Eiffert H, et al. Cardiac myocytes of hearts from patients with end-stage dilated cardiomyopathy do not contain borrelia burgdorferi DNA. Am Heart J. 1999;138:269–272. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(99)70111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Piccirillo BJ, Pride YB. Reading between the lyme: is borrelia burgdorferi a cause of dilated cardiomyopathy? The debate continues. Eur J Heart Fail. 2012;14:567–568. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waniek C, Prohovnik I, Kaufman MA, Dwork AJ. Rapidly progressive frontal-type dementia associated with lyme disease. J Neuropsychiatr Clin Neurosci. 1995;7:345–347. doi: 10.1176/jnp.7.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deresinski S. Sudden unexpected cardiac death from lyme disease. J Infect Dis. 2014;33:37–39. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tavora F, Burke A, Li L, Franks TJ, Virmani R. Postmortem confirmation of lyme carditis with polymerase chain reaction. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2008;17:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2007.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Kugeler KJ, Griffith KS, Gould LH, et al. A review of death certificates listing lyme disease as a cause of death in the United States. Clin Inf Dis. 2011;52:364–367. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e2.Cadavid D, Bai Y, Holzic E, Narayan K, Barthold SW, Pachner AR. Cardiac involvement in non-human primates infected with the lyme disease spirochete borrelia burgdorferi. Lab Invest. 2004;84:1439–1450. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Karaday B, Spieker E, Schwitter J. Lyme carditis: restitutio ad integrum documented by cardiac MRI. Cardiol Rev. 2004;12 doi: 10.1097/01.crd.0000123841.02777.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Maher B, Murday D, Harden SP. Cardiac MRI of lyme disease myocarditis. Heart. 2012;98:264–266. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-301070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e5.Raveche ES, Schutzer SE, Fernandes H, et al. Evidence of borrelia autoimmunity-induced component of lyme and arthritis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:850–856. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.2.850-856.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e6.Moter SE, Hofmann H, Wallich R, Simon MM, Kramer MD. Detection of borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in lesional skin of patients with erythema migrans and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans by ospA-specific PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2980–2988. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.12.2980-2988.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e7.Karatolios K, Maisch B, Pankuweit S. Suspected inflammatory cardiomyopathy: Prevalence of borrelia burgdorferi in endomyocardial biopsies with positive serological evidence. Herz. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00059-014-4118-x. [online first]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e8.Cornuau L, Bernard M, Daumas PL, Oblet B, Poirot G, Valois M. Les manifestations cardiaques de la maladie de lyme: a propos de deux observations. Ann Cardiol Angeiol. 1984;33:395–399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e9.Kapusta R, Fauchier JP, Cosnay P, Huguet R, Grezard O, Rouesnel P. Troubles conductivs sinuauriculaires et auriculo-ventriculaires de la maladie de lyme: a propos de deux observations. Arch Mal Coeur. 1986;79:1361–1366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e10.Konopka M, Kuch M, Braksator W, et al. Unclassified cardiomyopathy or lyme carditis ? A three year follow-up. Kardiol Pol. 2013;71:283–285. doi: 10.5603/KP.2013.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e11.Rees DH, Keeling PJ, McKenna WJ, Axford JS. No evidence to implicate borrelia burgdorferi in the pathogenesis of dilated cardiomyopathy in the United Kingdom. Br Heart J. 1994;71:459–461. doi: 10.1136/hrt.71.5.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e12.Kirsch M, Ruben FL, Steere AC, Duray PH, Norden CW, Winkelstein A. Fatal adult respiratory distress syndrome in a patient with lyme disease. JAMA. 1988;259:2737–2739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e13.Reimers CD, de Koning J, Neubert U, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi myositis: report of eight patients. J Neurol. 1993;240:278–283. doi: 10.1007/BF00838161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]