Summary

Of all breast cancer cases, 5–10% can be attributed to germline mutations, and the high-susceptibility genes BRCA1 and BRCA2 account for about 25–28% of these cases. For the remainder, several genes of moderate and low penetrance have been discovered. Histopathologic characteristics have been studied in small cohorts, but for most of the known non-BRCA1/2-associated hereditary breast cancers, the histologic and immunohistochemical phenotypes are not yet identified. Particularly BRCA1 tumors are associated with a distinct morphology and immunohistochemical characteristics that differ from sporadic breast cancer of age-matched controls. The recognition of features characteristic of these mutations can be helpful to identify patients likely to carry a germline mutation and to assess which gene should be screened for first, in families with a high occurrence of breast and ovarian cancer.

Keywords: Intrinsic subtypes, Hereditary breast cancer, BRCA mutation, Genotype/phenotype correlations

Introduction

A certain proportion of 5–10% of the breast cancer cases can be attributed to germline mutations [1]. Since the identification of BRCA1 and BRCA2 as the first genes with germline mutations over 20 years ago [2, 3], several other mutations associated with a higher susceptibility for the development of mammary carcinomas have been discovered.

Over the past 15 years, an increased understanding of the molecular mechanisms behind breast cancer heterogeneity has led to the identification of genetically defined ‘intrinsic’ subtypes [4, 5] associated with different clinical outcomes [6], responses to therapy [7], and preferential sites of relapse [8].

Intrinsic Subtypes of Breast Cancer

The numerous histopathological subtypes of breast cancer and the great variability in response to therapy and clinical outcome of tumors with apparently homogenous morphology [9, 10] show the limitations of the traditional clinicopathological classification.

Transferring the findings of molecular profiling of breast cancer [4] to the everyday clinicopathological diagnostic routine, the St. Gallen consensus meeting 2011 acknowledged the immunohistochemical markers estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), and Ki-67 as ‘surrogate markers’ for the identification of the intrinsic subtypes [11]. However, the discrimination by use of these biomarkers is a pragmatic approach aimed at the therapeutic consequences (i.e. treatment recommendations for systemic therapy proposed by the consensus meeting), as the thereby identified subtypes are similar but not identical to the intrinsic subtypes selected by gene expression analysis [11]. Today, the existence of at least 4 intrinsic subtypes is established.

The luminal subtype is characterized by expression of the ER and of other genes that encode proteins characteristic of the luminal epithelial cells [9]; up to 60% of breast cancers fall into this category [12]. Depending on the expression levels, a further subdivision into the luminal A and luminal B subgroups is made (fig. 1) [6, 9]. Luminal A tumors are characterized by high expression of estrogen-related and low expression of proliferation-related genes, whereas luminal B tumors are characterized by lower expression of estrogen-related and low expression of PR genes and higher expression of proliferation-related genes [6]; these profiles can be reproduced by immunohistochemistry.

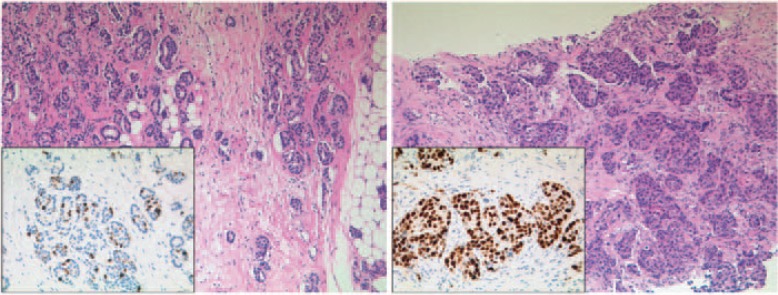

Fig. 1.

1. Luminal subtypes of breast cancer. (Left) Luminal A breast cancer, (right) luminal B breast cancer. Hematoxylin and eosin staining, 100 × magnification, each with corresponding Ki-67 immunohistochemistry (insert, 200 × magnification).

The basal-like subtype accounts for 15–20% of breast cancers [12] and is named for its expression of genes characteristic of the basal-myoepithelial cells of the normal breast [4, 9]. A defined immunohistochemical profile for the identification of this subtype does not exist, but basal-like carcinomas typically lack expression of hormone receptors or HER2 (‘triple negative breast cancer’) [9], so that the majority of basal-like cancers can be classified as triple negative and vice versa, with a concordance of approximately 80% (18–40% of basal-like cancers do not have a triple-negative phenotype on immunohistochemical analysis) [13, 14, 15].

About 10–15% of breast cancers belong to the subgroup of HER2-enriched tumors [5, 12], which are characterized by high expression levels of genes located in the HER2 amplicon on 17q21 [9].

Pathological Characteristics of Hereditary Breast Cancers

Of all human breast cancers, hereditary forms represent a minor percentage (5–10%). Taken together, the high-susceptibility genes BRCA1/2 are responsible for about 25–28% of the hereditary breast cancer cases [16, 17]; other germline mutations of high, intermediate, and low penetrance account for about 20% of the breast cancer cases [17]. In summary, for over 50% of the hereditary breast cancer cases, no mutation has as yet been identified. It is not likely that another high-penetrance gene (comparable to BRCA1 or BRCA2) will be found for this group; the familial risk is probably due to multiple genes of lower penetrance (polygenic model) [18] or a germline mutation in a moderate-penetrance gene still to be identified [17].

The BRCA1 gene was first identified in 1990 by Hall et al. [2]. It localizes to the long arm of chromosome 17 (17q21) and is involved in the regulation of the cellular response to DNA damage by mediating the repair of double-strand breaks through homologous recombination [1, 19]. It is estimated that carriers of BRCA1 mutations have a cumulative risk of 57% for the development of breast cancer and of 40% for ovarian cancer by the age of 70 years [20]. Other cancers associated with BRCA1 mutations include prostate cancer, pancreatic cancer, and cancer of the uterine body and cervix [21].

In terms of histological types, most BRCA1-associated breast cancers are invasive ductal adenocarcinomas of no special type (NST) and of higher grade than sporadic breast cancers [1, 22, 23]. They have higher mitotic indices and show a high frequency of necrotic areas and a higher proportion of continuous pushing margins and lymphocytic infiltration [1]. Interestingly, there is a remarkable overrepresentation of carcinomas with medullary features in the BRCA1 group (13% ‘medullary carcinomas’ vs. 2% controls) and, additionally, a large proportion of BRCA1 carcinomas exhibit some medullary features (hence meeting the diagnostic criteria for ‘atypical medullary carcinomas’) [24]. Carcinomas with medullary features comprise a histological subtype demonstrating all or some of the following characteristics: poor differentiation, high mitotic count, solid sheet-like growth pattern with well-defined pushing borders, and diffuse lymphocytic infiltration [25] (fig. 2). They are associated with a particularly favorable prognosis, probably due to a low incidence of lymph node metastasis [25, 26]. Eisinger et al. [26] found that a proportion of 11% of the ‘medullary carcinomas’ carry BRCA1 germline mutations.

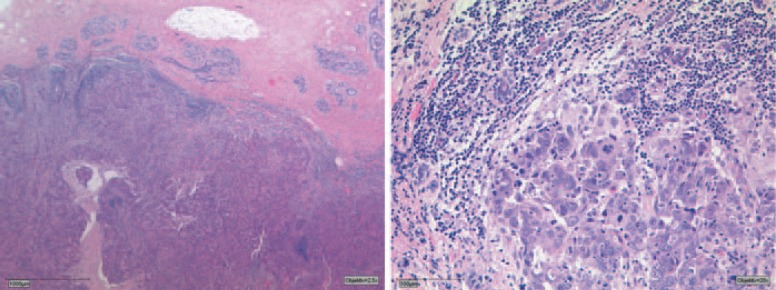

Fig. 2.

Carcinoma with medullary features. Example for the morphologic characteristics of BRCA1 tumors. Pushing margins, prominent lymphoid infiltration (overview left), geographic areas of necrosis may be present. Marked cellular atypia with distinct nucleoli and high mitotic index (detail right). Hematoxylin and eosin staining, 25 × and 200 × magnification.

Concerning immunohistochemical markers of prognostic and predictive relevance, Mavaddat et al. [27] observed in a large data set of 4,325 BRCA1 mutation carriers that 78% of the tumors were ER negative; overexpression of HER2 could be shown in approximately 10% of the cases and 69% were triple negative. The high mitotic count was corroborated by a high proliferation index (i.e. nuclear Ki-67 staining of > 20% of the tumor cells) [23].

Compared to sporadic tumors, BRCA1-associated tumors more often express several markers characteristic of basal/myoepithelial breast cells, including cytokeratin (CK)5/6, CK14, caveolin, vimentin, laminin, P-cadherin, osteonectin, and the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [28, 29]. In terms of the intrinsic subtypes, the majority of the BRCA1 breast cancers can thus be classified as basal like [1, 17]. Furthermore, BRCA1 tumors more often stained p53 positive in comparison to sporadic tumors [1, 23], probably reflecting the higher frequency of mutations in the TP53 gene found in BRCA1 tumors [30, 31].

The BRCA2 gene maps to the long arm of chromosome 13 (13q12–13). It is involved in the maintenance of genomic stability, specifically in the error-free repair of double-stranded DNA breaks through homologous recombination [1, 32]. Carriers of BRCA2 mutations have a cumulative risk of approximately 49% of developing breast cancer and of 18% for developing ovarian cancer by the age of 70 years [20]. Other associated malignancies include male breast cancer, cancer of the fallopian tube, prostate cancer, gastrointestinal cancers (pancreas, gall bladder, bile duct, stomach) and malignant melanoma of the skin [1, 33].

Like BRCA1-associated tumors and sporadic carcinomas, breast cancers arising in BRCA2 mutation carriers are mostly invasive ductal adenocarcinomas of NST with a moderate or poor differentiation, high mitotic counts, and continuous pushing margins [1, 22, 23]. There is contradictory information regarding an association with a special histologic subtype. Some authors reported a higher incidence of pleomorphic lobular carcinomas [34] while in other collectives a statistically significant association to a histological subtype could not be observed [24, 35].

Immunohistochemically, BRCA2 tumors seem to be more similar to sporadic tumors. Mavaddat et al. [27] found ER negativity in 23% of tumors arising in BRCA2 mutation carriers, HER2 overexpression in approximately 10%, and triple negativity in 16%, when investigating a large collective of 2,568 BRCA2 mutation carriers. The overexpression of ER, PR, CK8, and CK18 assigns BRCA2 tumors to the luminal intrinsic subtype [1, 23], with the vast majority belonging to the luminal B subtype [36, 37].

Non-BRCA1/2-associated hereditary breast cancers are responsible for the remaining 72–75% of familial cases. All in all, half of the cancer-related genes in hereditary breast cancer are still unidentified [17]. Many cancer syndromes and germline mutations are currently under investigation for their potential morphologic correlations [38].

The RAD51C gene is a rare high-penetrance breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility gene which encodes a DNA double-strand break repair protein and is localized on the long arm of chromosome 17 (17q23) [39]. Meindl et al. [39] identified several pathogenic RAD51C mutations in BRCA1/2 mutation-negative hereditary breast and ovarian cancer families. In their collective, the mean onset of breast cancer was 53 years, and the majority of the patients had intermediate-grade invasive ductal carcinoma, mostly hormone receptor positive and HER2 negative, indicating more favorable histopathological features in comparison to BRCA1-associated breast cancer. These findings were corroborated by Gevensleben et al. [23] who compared a large cohort of RAD51C-mutated breast cancer cases to breast cancer cases harboring BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in regard to clinicopathological and immunohistochemical features and found a resemblance to BRCA2-related cancers. Regarding the immunohistochemical profile of RAD51C breast cancers, Gevensleben et al. [23] observed high levels of luminal CKs, E-cadherin, activating enhancer binding protein 2 (AP-2) alpha and AP-2 gamma. In direct comparison to BRCA2-associated breast cancers, the proliferation marker Ki-67 was found to be the only discriminating feature, with significantly higher expression in BRCA2-associated breast cancers, indicating that RAD51C-related breast tumors belong to the intrinsic subtype of ‘luminal A’ breast cancers and thus are associated with a more favorable outcome. The lack of features characteristic of the BRCA1 phenotype, such as marked p53 expression or histopathological criteria of the medullary subtype, was also noted by the authors [23].

The CHEK2 gene (coding for checkpoint kinase 2) is a tumor suppressor gene located on the long arm of chromosome 22 (22q12.1) [40]. It encodes a nuclear protein which, in response to DNA damage (i.e. double-strand breaks), is phosphorylated by ATM and subsequently catalyzes the phosphorylation of several substrates, thereby regulating cell cycle progression and protecting cells against too rapid, uncontrolled growth [40, 41, 42].

Mutations of CHEK2 predispose to several types of common cancer, e.g. breast cancer and prostate cancer [43, 44]. Several different CHEK2 mutations have been described [40, 42], 5 of which have been associated with increased breast cancer risks. These CHEK2 variants appear to confer moderate breast cancer risks (2–4-fold) and seem to vary widely among different geographical and ethnic populations [45]. Domagala et al. [42] investigated the association between CHEK2 mutations and the immunophenotypic intrinsic subtypes of breast cancer in a large collective of CHEK2 mutation carriers and controls. They found that CHEK2-associated cancers were predominantly luminal, with significant associations of the CHEK2-I157T variant with the luminal A subtype, and of truncating CHEK2 mutations with the luminal B subtype. In a collective of 26 breast tumors from CHEK2 1100delC carriers analyzed by Nagel et al. [46], all tumors could be assigned to the luminal intrinsic subtype (8 tumors luminal A, 18 tumors luminal B). With respect to histopathological characteristics, an association between lobular carcinoma and the I157T missense mutation was reported by different authors [47, 48]. It was observed that CHEK2-associated tumors were more likely to be of multicentric origin and presented as larger tumors (> 2 cm) [48].

Conclusions

For the identification of mutation carriers, age at the time of tumor diagnosis and family history are the best predictors [22]. To identify the responsible gene, histopathologic evaluation can be crucial, as especially BRCA1 breast cancers are associated with distinct morphology and immunohistochemical characteristics and differ from sporadic breast cancers of age-matched controls [22]. Studies have demonstrated that the inclusion of morphologic and immunohistologic breast cancer characteristics in models of risk estimation improves the accuracy in predicting the BRCA status [28, 49]. The German S3 medical guideline for diagnosis, therapy and follow-up care of breast cancer proposes that the pathologist should report the possibility of a hereditary background when encountering suggestive histopathological features. Non-BRCA1/2 mutations are responsible for the majority of hereditary breast cancer cases; the known non-BRCA1/2-associated hereditary breast cancers comprise a heterogeneous group of tumors, for most of which the histologic and immunohistochemical phenotypes are yet to be identified. Due to the low frequencies of these mutations, it is difficult to obtain sufficiently large collectives to be able to establish a phenotype. Moreover, it has been postulated that a large percentage of the familial clustering in breast cancer might be due to a polygenic setting, with several moderate- and/or low-risk breast cancer susceptibility alleles conferring significantly increased breast cancer risks [45, 50, 51]. Individual family trees with the involvement of several breast cancer susceptibility genes adding up to an overall increased risk might make it difficult to identify characteristic histological profiles for the remainder of the hereditary breast cancer cases.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Larsen MJ, Thomassen M, Gerdes AM, Kruse TA. Hereditary breast cancer: clinical, pathological and molecular characteristics. Breast Cancer (Auckl) 2014;8:145–155. doi: 10.4137/BCBCR.S18715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall JM, Lee MK, Newman B, Morrow JE, Anderson LA, Huey B, et al. Linkage of early-onset familial breast cancer to chromosome 17q21. Science. 1990;250:1684–1689. doi: 10.1126/science.2270482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stratton MR, Ford D, Neuhasen S, Seal S, Wooster R, Friedman LS, et al. Familial male breast cancer is not linked to the BRCA1 locus on chromosome 17q. Nat Genet. 1994;7:103–107. doi: 10.1038/ng0594-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey SS, Rees CA, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–752. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cancer Genome Atlas Network: Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2012;490:61–70. doi: 10.1038/nature11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sorlie T, Tibshirani R, Parker J, Hastie T, Marron JS, Nobel A, et al. Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8418–8423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932692100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rouzier R, Perou CM, Symmans WF, Ibrahim N, Cristofanilli M, Anderson K, et al. Breast cancer molecular subtypes respond differently to preoperative chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5678–5685. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smid M, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Sieuwerts AM, Yu J, Klijn JG, et al. Subtypes of breast cancer show preferential site of relapse. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3108–3114. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rakha EA, Reis-Filho JS, Ellis IO. Basal-like breast cancer: a critical review. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2568–2581. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alizadeh AA, Ross DT, Perou CM, van de Rijn M. Towards a novel classification of human malignancies based on gene expression patterns. J Pathol. 2001;195:41–52. doi: 10.1002/path.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldhirsch A, Wood WC, Coates AS, Gelber RD, Thurlimann B, Senn HJ. Strategies for subtypes – dealing with the diversity of breast cancer: highlights of the St. Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2011. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1736–1747. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Malhotra GK, Zhao X, Band H, Band V. Histological, molecular and functional subtypes of breast cancers. Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;10:955–960. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.10.13879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bertucci F, Finetti P, Cervera N, Esterni B, Hermitte F, Viens P, et al. How basal are triple-negative breast cancers? Int J Cancer. 2008;123:236–240. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weigelt B, Baehner FL, Reis-Filho JS. The contribution of gene expression profiling to breast cancer classification, prognostication and prediction: a retrospective of the last decade. J Pathol. 2010;220:263–280. doi: 10.1002/path.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foulkes WD, Smith IE, Reis-Filho JS. Triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1938–1948. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gerdes AM, Cruger DG, Thomassen M, Kruse TA. Evaluation of two different models to predict BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in a cohort of Danish hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer families. Clin Genet. 2006;69:171–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melchor L, Benitez J. The complex genetic landscape of familial breast cancer. Hum Genet. 2013;132:845–863. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1299-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gracia-Aznarez FJ, Fernandez V, Pita G, Peterlongo P, Dominguez O, de la Hoya M, et al. Whole exome sequencing suggests much of non-BRCA1/BRCA2 familial breast cancer is due to moderate and low penetrance susceptibility alleles. PloS One. 2013;8:e55681. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huen MS, Sy SM, Chen J. BRCA1 and its toolbox for the maintenance of genome integrity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:138–148. doi: 10.1038/nrm2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen S, Parmigiani G. Meta-analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 penetrance. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1329–1333. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson D, Easton DF. Cancer incidence in BRCA1 mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1358–1365. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.18.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Honrado E, Benitez J, Palacios J. Histopathology of BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated breast cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2006;59:27–39. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gevensleben H, Bossung V, Meindl A, Wappenschmidt B, de Gregorio N, Osorio A, et al. Pathological features of breast and ovarian cancers in RAD51C germline mutation carriers. Virchows Arch. 2014;465:365–369. doi: 10.1007/s00428-014-1619-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pathology of familial breast cancer: differences between breast cancers in carriers of BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and sporadic cases. Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Lancet. 1997;349:1505–1510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ridolfi RL, Rosen PP, Port A, Kinne D, Mike V. Medullary carcinoma of the breast: a clinicopathologic study with 10 year follow-up. Cancer. 1977;40:1365–1385. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197710)40:4<1365::aid-cncr2820400402>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisinger F, Jacquemier J, Charpin C, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Bressac-de Paillerets B, Peyrat JP, et al. Mutations at BRCA1: the medullary breast carcinoma revisited. Cancer Res. 1998;58:1588–1592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mavaddat N, Barrowdale D, Andrulis IL, Domchek SM, Eccles D, Nevanlinna H, et al. Pathology of breast and ovarian cancers among BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from the Consortium of Investigators of Modifiers of BRCA1/2 (CIMBA) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:134–147. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lakhani SR, Reis-Filho JS, Fulford L, Penault-Llorca F, van der Vijver M, Parry S, et al. Prediction of BRCA1 status in patients with breast cancer using estrogen receptor and basal phenotype. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5175–5180. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Groep P, van der Wall E, van Diest PJ. Pathology of hereditary breast cancer. Cell Oncol (Dordr) 2011;34:71–88. doi: 10.1007/s13402-011-0010-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crook T, Brooks LA, Crossland S, Osin P, Barker KT, Waller J, et al. p53 mutation with frequent novel codons but not a mutator phenotype in BRCA1- and BRCA2-associated breast tumours. Oncogene. 1998;17:1681–1689. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greenblatt MS, Chappuis PO, Bond JP, Hamel N, Foulkes WD. TP53 mutations in breast cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 germ-line mutations: distinctive spectrum and structural distribution. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4092–4097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Apostolou P, Fostira F. Hereditary breast cancer: the era of new susceptibility genes. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:747318. doi: 10.1155/2013/747318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Asperen CJ, Brohet RM, Meijers-Heijboer EJ, Hoogerbrugge N, Verhoef S, Vasen HF, et al. Cancer risks in BRCA2 families: estimates for sites other than breast and ovary. J Med Genet. 2005;42:711–719. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.028829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armes JE, Egan AJ, Southey MC, Dite GS, McCredie MR, Giles GG, et al. The histologic phenotypes of breast carcinoma occurring before age 40 years in women with and without BRCA1 or BRCA2 germline mutations: a population-based study. Cancer. 1998;83:2335–2345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lakhani SR, Jacquemier J, Sloane JP, Gusterson BA, Anderson TJ, van de Vijver MJ, et al. Multifactorial analysis of differences between sporadic breast cancers and cancers involving BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1138–1145. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.15.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jonsson G, Staaf J, Vallon-Christersson J, Ringner M, Gruvberger-Saal SK, Saal LH, et al. The retinoblastoma gene undergoes rearrangements in BRCA1-deficient basal-like breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:4028–4036. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larsen MJ, Kruse TA, Tan Q, Laenkholm AV, Bak M, Lykkesfeldt AE, et al. Classifications within molecular subtypes enables identification of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutation carriers by RNA tumor profiling. PloS One. 2013;8:e64268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vargas AC, Reis-Filho JS, Lakhani SR. Phenotype-genotype correlation in familial breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2011;16:27–40. doi: 10.1007/s10911-011-9204-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meindl A, Hellebrand H, Wiek C, Erven V, Wappenschmidt B, Niederacher D, et al. Germline mutations in breast and ovarian cancer pedigrees establish RAD51C as a human cancer susceptibility gene. Nat Genet. 2010;42:410–414. doi: 10.1038/ng.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tedaldi G, Danesi R, Zampiga V, Tebaldi M, Bedei L, Zoli W, et al. First evidence of a large CHEK2 duplication involved in cancer predisposition in an Italian family with hereditary breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:478. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Antoni L, Sodha N, Collins I, Garrett MD. CHK2 kinase: cancer susceptibility and cancer therapy – two sides of the same coin? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:925–936. doi: 10.1038/nrc2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Domagala P, Wokolorczyk D, Cybulski C, Huzarski T, Lubinski J, Domagala W. Different CHEK2 germline mutations are associated with distinct immunophenotypic molecular subtypes of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132:937–945. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1635-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dong X, Wang L, Taniguchi K, Wang X, Cunningham JM, McDonnell SK, et al. Mutations in CHEK2 associated with prostate cancer risk. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:270–280. doi: 10.1086/346094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cybulski C, Gorski B, Huzarski T, Masojc B, Mierzejewski M, Debniak T, et al. CHEK2 is a multiorgan cancer susceptibility gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:1131–1135. doi: 10.1086/426403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hollestelle A, Wasielewski M, Martens JW, Schutte M. Discovering moderate-risk breast cancer susceptibility genes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2010;20:268–276. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagel JH, Peeters JK, Smid M, Sieuwerts AM, Wasielewski M, de Weerd V, et al. Gene expression profiling assigns CHEK2 1100delC breast cancers to the luminal intrinsic subtypes. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132:439–448. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1588-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huzarski T, Cybulski C, Domagala W, Gronwald J, Byrski T, Szwiec M, et al. Pathology of breast cancer in women with constitutional CHEK2 mutations. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;90:187–189. doi: 10.1007/s10549-004-3778-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cybulski C, Gorski B, Huzarski T, Byrski T, Gronwald J, Debniak T, et al. CHEK2-positive breast cancers in young Polish women. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4832–4835. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Farshid G, Balleine RL, Cummings M, Waring P. Morphology of breast cancer as a means of triage of patients for BRCA1 genetic testing. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1357–1366. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213273.22844.1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peto J. Breast cancer susceptibility – a new look at an old model. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:411–412. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Antoniou AC, Easton DF. Models of genetic susceptibility to breast cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25:5898–5905. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]