Abstract

Background

Lyme disease is a global public health problem caused by the spirochaete Borrelia burgdorferi. Our previous studies found differences in disease severity between B. burgdorferi B31- and B. garinii SZ-infected mice. We hypothesized that genes that are differentially expressed between Borrelia isolates encode bacterial factors that contribute to disease diversity.

Methods

The present study used high-throughput sequencing technology to characterize and compare the transcriptional profiles of B. burgdorferi B31 and B. garinii SZ cultured in vitro. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR was used to validate selected data from RNA-seq experiments.

Results

A total of 731 genes were differentially expressed between B. burgdorferi B31 and B. garinii SZ isolates, including those encoding lipoproteins and purine transport proteins. The fold difference in expression for B. garinii SZ versus B. burgdorferi B31 ranged from 22.07 to 1.01. Expression of the OspA, OspB and DbpB genes were significantly lower in B. garinii SZ compared to B. burgdorferi B31.

Conclusions

The results support the hypothesis that global changes in gene expression underlie differences in Borrelia pathogenicity. The findings also provide an empirical basis for studying the mechanism of action of specific genes as well as their potential usefulness for the diagnosis and management of Lyme disease.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s13071-014-0623-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Lyme disease, Gene expression, High-throughput sequencing, Transcriptional profile

Background

Borrelia burgdorferi is the causative agent of Lyme disease, the most prevalent tick-borne zoonosis and an important emerging infectious disease in Europe, North America, and Far Eastern countries [1]. The Borrelia burgdorferi complex consists of 18 proposed and confirmed genospecies [2]. The obligate parasites are transmitted by ticks of Ixodes spp., with disease symptoms and severity varying among B. burgdorferi genospecies. B. garinii is primarily associated with neuroborreliosis [3], B. afzelii with crodermatitis chronic athrophicans [4], and B. burgdorferi s.s is the major cause of Lyme arthritis [5].

Despite its small genome, the spirochaetes possess complex cellular machinery for regulating gene and protein expression. B. burgdorferi expresses specific subsets of genes throughout its life cycle, both in the arthropod vector and vertebrate host [6,7]. In one study of bacterial protein expression in infected mouse tissues, VlsE, OspC, and decorin-binding protein (Dbp)A were expressed at high levels in joints and dermal tissues, while OspC and DbpA were also detected in the heart [8], demonstrating tissue-specific protein expression. A comparative analysis of protein expression profiles of three strains of B. burgdorferi (B31, ND40, and JD-1) demonstrated large differences in the percentage of peptide coverage of proteins [9]. The application of genome, transcriptome, interactome, and immunoproteome analyses can reveal complexities of bacterial physiology and pathogenesis; in addition, the development of massively parallel cDNA sequencing (RNA-seq) techniques is enabling more comprehensive and accurate assessments of eukaryote [10] and prokaryote [11] transcriptomes.

Our previous studies found differences in disease severity between B. burgdorferi B31- and B. garinii SZ-infected mice, particularly affecting the brain, heart, liver, and spleen tissues [12]. Differential gene expression facilitates spirochaetal survival and promotes disease pathogenesis. In the present study, RNA-seq was employed to compare the transcriptome profiles of B. burgdorferi B31 and B. garinii SZ isolates during in vitro culture. The differences in gene expression profiles between the two species of spirochetes provide insights into disease-specific mechanisms.

Methods

Bacterial strains

B. burgdorferi B31 and B. garinii SZ were used in this study. B31 was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and had undergone five in vitro passages. B. garinii SZ was isolated from Dermacentor ticks collected in Shangzhi county of Heilongjiang province in China [13]. The strains were cultured in BSK-H medium in a 33°C incubator and observed under a dark-field microscope every other day. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at a speed of 5,000 × g during logarithmic phase and washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS).

RNA isolation

RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). RNA concentration and quality were assessed using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA) and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). RNA (10 μg) was pooled from three individual cells of each strain and used to construct two cDNA libraries following the mRNA sequencing sample preparation guide (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Paired-end DNA sequencing was carried out in two lanes (one per library) on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 following the manufacturer’s protocol. The 16S and 23S rRNA was removed from total RNA using the MICROBExpresst Bacterial mRNA Purification Kit (Ambion, Foster City, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Sequence assembly and annotation

The 100-bp paired-end Illumina reads from the B. burgdorferi B31 (82,056,756 reads) and B. garinii SZ (145,680,918 reads) libraries were combined for de novo assembly. Reads that were of low quality (≥80% with Phred score < 20) or complexity (>80% with single, di-, or trinucleotide repeats) or were < 20 bp were removed. The processed reads were then assembled using the CLC Genomics Workbench v.5.5 [14,15] with wordsize = 45 and minimum contig length ≥ 200. The resulting assembled sequences and singletons were combined and processed to remove duplicates using a custom Perl Script; contigs were then assembled using CAP3 EST to obtain the final unigenes.

Functional annotation of unigenes was achieved by searching for analogous sequences in EMBL and Swiss-Prot databases using an E-value ≤ 1e − 5. Hierarchical functional categorization for gene ontology (GO) terms was accomplished using BLAST2GO, which was also used to identify genes represented among the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways.

Real-time quantitative reverse transcription (qRT)-PCR

Real-time qRT-PCR was used to validate data from RNA-seq experiments. Gene-specific primers (Additional file 1: Table S7) were designed using Primer Express software (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The relative quantitation (ΔΔCt) method was used to evaluate differences between the two genospecies for each gene examined. The flaB amplicon was used as an internal control to normalize all data. Removal of genomic DNA and reverse transcription (Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Japan) were performed for each sample and standard without reverse transcriptase to confirm the absence of genomic DNA.

Results and discussion

Whole-transcriptome profiling of bacteria has been widely used to evaluate global changes in gene expression [16]. RNA-seq-based transcriptome analyses of pathogens during infection yields a robust, sensitive, and accessible dataset that enables the assessment of the regulatory interactions driving pathogenesis [11]. Our previous studies revealed differences in disease severity between B. burgdorferi B31- and B. garinii SZ-infected mice [12]; the present study used RNA-seq to determine the transcriptional profiles of B. burgdorferi B31 and B. garinii SZ isolates during in vitro infection. This is the first comprehensive analysis of gene expression in this organism; the findings are discussed in the context of pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of Lyme disease.

Sequence assembly and annotation

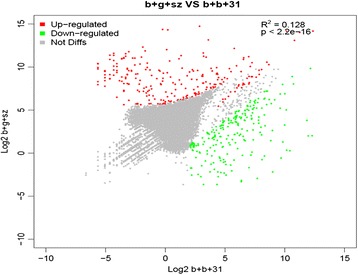

The 100-bp paired-end Illumina sequence reads from B. burgdorferi B31 (82,056,756 reads) and B. garinii SZ (145,680,918 reads) libraries were combined in a de novo assembly to obtain the final unigenes (89,827,575 bp) and 65,535 good quality contigs. Approximately 43.7% of transcripts (n = 28,610) mapped to the Swiss-Prot database (E < 10−4) based on deduced amino acid similarity. A total of 1,347 and 1,454 genes were generated for B. burgdorferi B31 and B. garinii SZ transcriptomes, respectively. Sequence reads mapped against the final unigenes were used to quantify gene expression levels based on the number of reads per kilobase of coding sequence per million mapped reads. On a more conservative level using Fisher’s exact test (false discovery rate < 0.05) and fold-change ≥ 2, a total of 731 genes were differentially expressed between B. burgdorferi B31 and B. garinii SZ isolates, with 288 genes upregulated and 443 genes downregulated in B. garinii SZ (Additional file 1: Tables S1 and S2 and Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Average log 2 -transformed reads per kilobase per million of genes differentially expressed by B. garinii SZ (y-axis) and B. burgdorferi B31 (x-axis). Red and green dots represent genes that are significantly up- and downregulated, respectively, in B. garinii SZ; gray dots represent genes that are not differentially expressed between the two species.

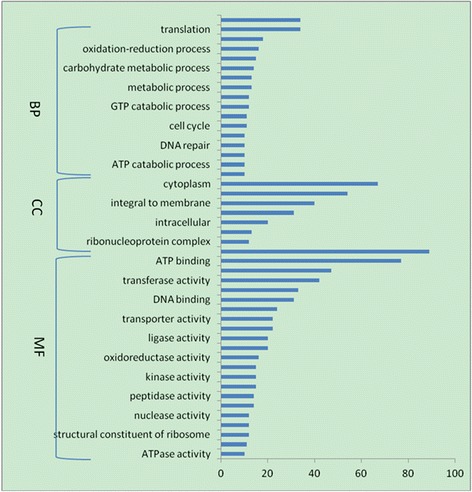

To determine the functional significance of differentially expressed genes, BLAST2GO was used to examine the associations between GO and biological function. A total of 264 genes mapping to GO terms were identified among upregulated genes (Additional file 1: Tables S3 and S4), as well as 439 genes mapping to GO terms among downregulated genes; of these, 343 were classified as having a molecular function, 306 were implicated in biological processes, and 71 encoded cellular components. When the analysis was restricted to genes with putative biological functions, the number of genes differentially expressed between the two isolates was consistently higher in all functional categories (Figures 2 and 3). Genes that were the most highly upregulated in B. garinii SZ were those encoding membrane-associated proteins (20.8%) and proteins with ATP-/nucleotide-binding function (23.2%). The most highly upregulated genes in B. burgdorferi B31 encoded cytoplasmic proteins (13.6%) and proteins with ATP-/nucleotide-binding function (18.2%). The KEGG pathway analysis revealed that 288 of the genes that were upregulated and 443 of the genes that were downregulated in B. garinii SZ could be assigned to one or more of 52 and 80 KEGG pathways, respectively (Additional file 1: Tables S5 and S6).

Figure 2.

Functional categories of genes upregulate in B.garinii SZ.

Figure 3.

Functional categories of genes upregulated in B. burgdorferi B31.

Lipoproteins

A large fraction of the Borrelia genome encodes lipoproteins such as the well-studied outer surface proteins (Osp). Several Borrelia proteins have been identified that interact with either host or tick ligands and thereby promote pathogen survival [17], which is facilitated by the differential expression of specific genes at various stages of the Borrelia infection cycle. This is best exemplified by the up-/downregulation of OspA–F, DbpA or B, multicopy lipoprotein (Mlp)-8, RNA polymerase sigma S, OspE/F-related proteins (Erp), and OspE/F-like proteins during tick feeding, transmission, and infection [18-22]. Differentially expressed genes with the highest levels of expression in B. burgdorferi B31 and B. garinii SZ are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The majority of genes encoded membrane proteins, which have important antigen-related functions. B. burgdorferi gene expression in the host are influenced by humoral and cellular immunity factors [23]. Complement regulator-acquiring surface proteins (CRASP) [24] and Erp bind factor H or four-and-a-half LIM domain protein, thereby inhibiting complement-mediated bactericidal activity [25]. The ability to inhibit complement varies between Borrelia genospecies: Erps have different affinities for factor H proteins from various animal hosts [26]. In the present analysis, CRASP and ErpA/D/P were upregulated in B. burgdorferi B31, while ErpY was upregulated in B. garinii SZ, indicating that the expression of Erp subtypes is species-specific (Additional file 1: Tables S1 and S2), which may cause different humoral and cellular immune responses in the host and contribute to the genotypic variation of B. burgdorferi in the pathogenicity of Lyme disease. This supports the hypothesis that global changes in gene expression underlie differences in Borrelia pathogenicity.

Table 1.

Genes with the highest transcript levels in B. garinii SZ

| Locus | Gene | Description | Log 2 (fold change) |

|---|---|---|---|

| G0IT27 | Erf | Erf superfamily protein | 26.27 |

| G0ANB6 | Mlp | Mlp lipofamily protein | 24.67 |

| B8DXK7 | OspE | Outer surface protein E | 22.66 |

| B8F1A2 | OspD | Outer surface protein D | 21.23 |

| K0DGB8 | BmpD | Basic membrane protein D | 22.49 |

| Q0SLT0 | P13 | Borrelia membrane P13 family protein | 21.61 |

| B9X9C0 | Rev protein | 21.00 | |

| C0R6G3 | ErpY | ErpY protein | 20.27 |

| D5BEM4 | Omp121 | Outer membrane protein Omp121 | 18.77 |

| K0DGT1 | P66 | Membrane-associated protein P66 | 11.96 |

| E4QH49 | BBD14-like protein | 19.83 | |

| K0DF80 | NifS protein | 19.91 |

Table 2.

Genes with the highest transcript levels in B. burgdorferi B31

| Locus | Gene | Description | Log 2 (fold change) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q547V1 G8W6T3 | DbpA/B | Decorin binding protein B DbpA/B | 24.49 |

| Q8KKG6 | OspA | Outer surface protein A | 23.19 |

| C6C2K1 | OspB | Outer surface protein B (OspB) | 14.11 |

| E4S1K9 | BmpA | Basic membrane protein A | 25.06 |

| Q9S036 | ErpP | Complement regulator-acquiring surface protein 3 precursor protein ErpP | 26.06 |

| O50951 | P27 | Surface lipoprotein P27 | 25.84 |

| O51398 | YidC | Membrane protein insertase YidC | 23.85 |

| E4QEQ3 | FliF | Flagellar M-ring protein FliF | 27.62 |

| O51576 | Uncharacterized protein | 30.99 | |

| E4S2W7 | Putative uncharacterized protein | 28.74 |

Purine transport proteins

The uptake of preformed purines by spirochete represents the first step in the purine salvage pathway, which is critical for the infection of mammalian hosts by B. burgdorferi. The genes bbb22 and bbb23, which are present on circular plasmid 26, encode key purine transport proteins that are essential for hypoxanthine, adenine, and guanine transport [27], while inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase (encoded by GuaB) and guanosine monophoshpate synthase (encoded by GuaA) are two key enzymes in the purine salvage pathway [28]. GuaA and B were significantly upregulated in B. burgdorferi B31 as compared to B. garinii SZ (Additional file 1: Tables S1 and S2). Genes encoding bifunctional purine biosynthesis protein (PurH) and non-canonical purine nucleoside triphosphate (NTP) pyrophosphatase were also identified. These findings suggest that this transport system is a potential target for antimicrobial agents in the treatment of Lyme disease.

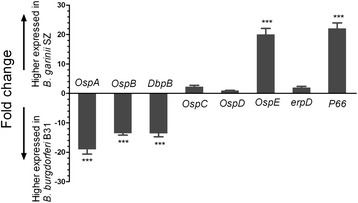

Confirmation of RNA-seq data by qRT-PCR

The expression levels of select genes—particularly those encoding lipoproteins and/or surface proteins—were confirmed by qRT-PCR. RNA isolated from B. burgdorferi B31 and B. garinii SZ isolates had an A260/A280 between 1.8 and 2, indicating high purity, and the PCR efficiency for each primer set was below 0.1 (Additional file 1: Table S7). The fold difference in expression levels for B. garinii SZ vs. B. burgdorferi B31 ranged from 22.07 to 1.01 (Figure 4). There were no differences between the two species in OspC, OspD, and erpD expression; however, OspA, OspB, and DbpB expression levels were significantly lower in B. garinii SZ than in B. burgdorferi B31. DbpA and B bind to the host extracellular matrix component decorin [29], and decorin-deficient mice infected with B. burgdorferi show reduced Borrelia numbers and less arthritis than infected wild-type controls [30]. The high expression of DbpA and B in B. burgdorferi B31 may be associated with arthritis severity and could explain the wide global distribution of this genospecies. OspA/B function was not required for infection of mice or accompanying tissue pathology, but was essential for the colonization of and survival within tick midgut by B. burgdorferi, events that are critical for sustaining its natural enzootic life cycle [31].

Figure 4.

Expression profiles of genes encoding Borrelia membrane proteins detected by qRT-PCR. Each bar represents the fold change of gene expression in B. garinii SZ vs. B. burgdorferi B31. Expression levels were nomalized to that of flaB, and levels in B. burgdorferi B31 were used to calculate fold change based on a mean of three biological replicates. Bars above and below the x-axis show genes that are up- and downregulated, respectively, in B. garinii SZ. ΔΔCt values were analyzed with the Student’s t test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Given the increasing incidence of and medical concerns related to Lyme disease, vaccination, drug treatment, and pathogenic mechanisms have received considerable attention. Some insight is gained from the study of other faculative pathogens such as those responsible for cholera and malaria using high-throughput cDNA sequencing techniques on organisms grown in laboratory medium or isolated from infected hosts [11,32]. Thus, RNA-seq-based transcriptome analyses of pathogens during infection offer robust, sensitive, and accessible datasets for evaluating regulatory mechanisms driving pathogenesis [33].

Conclusions

The availability of fully sequenced genomes offers new opportunities to identify genotype–phenotype relationships and undertake global genomic, proteomic, and transcriptomic analyses to investigate the biological significance of paralogous gene families and other unique features of genomes. The present study is the first to characterize the transcriptome of B. burgdorferi, the causative agent of Lyme disease. Some novel genes, including a bifunctional PurH and non-canonical purine NTP pyrophosphatase, were also identified that could potentially be targeted by antimicrobial agents for disease treatment. Moreover, the differential expression of specific factors observed between Borrelia genospecies could explain the variation in disease pathogenicity. These findings provide a framework for future studies examining the molecular mechanisms underlying the pathogenicity of Lyme disease.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the “973” Program (2010CB530206),NSFC (31272556, 30972182, 31072130, 31001061), “948” (2010-S04), Key Project of Gansu Province (1002NKDA035), NBCITS. MOA (CARS-38), Specific Fund for Sino-Europe Cooperation, MOST, China, State Key Laboratory of Veterinary Etiological Biology Project (SKLVEB2008ZZKT019). The research was also facilitated by EPIZONE (FOOD-CT-2006-016236), ASFRISK (211691), ARBOZOONET (211757) and PIROVAC (KBBE-3-245145) of the European Commission, Brussels, Belgium.

Additional file

Tables S1. Using Fisher’s exact test (false discovery rate < 0.05) and fold-change ≥ 2, with 288 upregulated genes in B. garinii SZ. Tables S2: Using Fisher’s exact test (false discovery rate < 0.05) and fold-change ≥ 2, with 443 downregulated genes in B. garinii SZ (upregulated in B. burgdorferi B31). Tables S3. A total of 264 genes mapping to GO terms were identified among upregulated genes in B. garinii SZ. Tables S4. A total of 439 genes mapping to GO terms among downregulated genes in B. garinii SZ (upregulated in B. burgdorferi B31). Tables S5. The KEGG pathway analysis of the genes that were upregulated in B. garinii SZ. Tables S6. The KEGG pathway analysis of the genes that were downregulated in B. garinii SZ (upregulated in B. burgdorferi B31). Tables S7. The primer and the PCR efficiency for each selected genes.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

QW designed the experimental. QW and GG carried out most of the experiments. YL and ZL participated in the design of the study and helped experimental development. QW and ZL drafted the manuscript. JL and HY conceived, coordinated and provided financial support for the study. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Qiong Wu, Email: wubinbin02@163.com.

Guiquan Guan, Email: guanguiquan@163.com.

Zhijie Liu, Email: lvrilzj@hotmail.com.

Youquan Li, Email: youquanli@163.com.

Jianxun Luo, Email: ljxbn@163.com.

Hong Yin, Email: yinhong@caas.net.cn.

References

- 1.Steere AC, Coburn J, Glickstein L. The emergence of Lyme disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1093–101. doi: 10.1172/JCI21681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Margos G, Hojgaard A, Lane RS, Cornet M, Fingerle V, Rudenko N, et al. Multilocus sequence analysis of Borrelia bissettii strains from North America reveals a new Borrelia species, Borrelia kurtenbachii. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2010;1:151–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilske B, Busch U, Eiffert H, Fingerle V, Pfister H-W, Rössler D, et al. Diversity of OspA and OspC among cerebrospinal fluid isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato from patients with neuroborreliosis in Germany. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1996;184:195–201. doi: 10.1007/BF02456135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canica MM, Nato F, Merle L, Mazie JC, Baranton G, Postic D. Monoclonal antibodies for identification of Borrelia afzelii sp. nov. associated with late cutaneous manifestations of Lyme borreliosis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1993;25:441–8. doi: 10.3109/00365549309008525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lünemann JD, Zarmas S, Priem S, Franz J, Zschenderlein R, Aberer E, et al. Rapid typing of Borrelia burgdorferisensu lato species in specimens from patients with different manifestations of Lyme borreliosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:1130–3. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.3.1130-1133.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lederer S, Brenner C, Stehle T, Gern L, Wallich R, Simon MM. Quantitative analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi gene expression in naturally (tick) infected mouse strains. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2005;194:81–90. doi: 10.1007/s00430-004-0218-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samuels DS. Gene regulation in Borrelia burgdorferi. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2011;65:479–99. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crother TR, Champion CI, Wu XY, Blanco DR, Miller JN, Lovett MA. Antigenic composition of Borrelia burgdorferi during infection of SCID mice. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3419–28. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3419-3428.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs JM, Yang X, Luft BJ, Dunn JJ, Camp DG, II, Smith RD. Proteomic analysis of Lyme disease: global protein comparison of three strains of Borrelia burgdorferi. Proteomics. 2005;5:1446–53. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ozsolak F, Milos PM. RNA sequencing: advances, challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;12:87–98. doi: 10.1038/nrg2934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mandlik A, Livny J, Robins WP, Ritchie JM, Mekalanos JJ, Waldor MK. RNA-Seq-Based Monitoring of Infection-Linked Changes in Vibrio cholerae Gene Expression. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:165–74. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Q, Liu Z, Wang J, Li Y, Guan G, Yang J, et al. Pathogenic analysis of Borrelia garinii strain SZ isolated from northeastern China. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:177. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niu Q, Yang J, Guan G, Fu Y, Ma M, Li Y, et al. Identification and phylogenetic analysis of Lyme disease Borrelia spp. isolated from Shangzhi Prefecture of Heilongjiang Province. Chin Vet Sci. 2010;40:551–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.C-l S, Chao Y-T, Chang Y-CA, Chen W-C, Chen C-Y, Lee A-Y, et al. De novo assembly of expressed transcripts and global analysis of the Phalaenopsis aphrodite transcriptome. Plant Cell Physiol. 2011;52:1501–14. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcr097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garg R, Patel RK, Tyagi AK, Jain M. De novo assembly of chickpea transcriptome using short reads for gene discovery and marker identification. DNA Res. 2011;18:53–63. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsq028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wehrly TD, Chong A, Virtaneva K, Sturdevant DE, Child R, Edwards JA, et al. Intracellular biology and virulence determinants of Francisella tularensis revealed by transcriptional profiling inside macrophages. Cell Microbiol. 2009;11:1128–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01316.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brisson D, Drecktrah D, Eggers CH, Samuels DS. Genetics ofBorrelia burgdorferi. Annu Rev Genet. 2012;46:515–36. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-011112-112140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodzic E, Feng S, Freet KJ, Barthold SW. Borrelia burgdorferi population dynamics and prototype gene expression during infection of immunocompetent and immunodeficient mice. Infect Immun. 2003;71:5042–55. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.9.5042-5055.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang X, Goldberg MS, Popova TG, Schoeler GB, Wikel SK, Hagman KE, et al. Interdependence of environmental factors influencing reciprocal patterns of gene expression in virulent Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:1470–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hefty PS, Jolliff SE, Caimano MJ, Wikel SK, Akins DR. Changes in temporal and spatial patterns of outer surface lipoprotein expression generate population heterogeneity and antigenic diversity in the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 2002;70:3468–78. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.7.3468-3478.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hefty PS, Jolliff SE, Caimano MJ, Wikel SK, Radolf JD, Akins DR. Regulation of OspE-related, OspF-related, and Elp lipoproteins of Borrelia burgdorferi strain 297 by mammalian host-specific signals. Infect Immun. 2001;69:3618–27. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.6.3618-3627.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stevenson B, Bono JL, Schwan TG, Rosa P. Borrelia burgdorferi Erp proteins are immunogenic in mammals infected by tick bite, and their synthesis is inducible in cultured bacteria. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2648–54. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2648-2654.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang FT, Nelson FK, Fikrig E. Molecular adaptation of Borrelia burgdorferi in the murine host. J Exp Med. 2002;196:275–80. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kraiczy P, Skerka C, Kirschfink M, Brade V, Zipfel PF. Immune evasion of Borrelia burgdorferi by acquisition of human complement regulators FHL 1/reconectin and Factor H. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1674–84. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200106)31:6<1674::AID-IMMU1674>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alitalo A, Meri T, Lankinen H, Seppälä I, Lahdenne P, Hefty PS, et al. Complement inhibitor factor H binding to Lyme disease spirochetes is mediated by inducible expression of multiple plasmid-encoded outer surface protein E paralogs. J Immunol. 2002;169:3847–53. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stevenson B, El-Hage N, Hines MA, Miller JC, Babb K. Differential binding of host complement inhibitor factor H by Borrelia burgdorferi Erp surface proteins: a possible mechanism underlying the expansive host range of Lyme disease spirochetes. Infect Immun. 2002;70:491–7. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.2.491-497.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jain S, Sutchu S, Rosa PA, Byram R, Jewett MW. Borrelia burgdorferi Harbors a Transport System Essential for Purine Salvage and Mammalian Infection. Infect Immun. 2012;80:3086–93. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00514-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jewett MW, Lawrence KA, Bestor A, Byram R, Gherardini F, Rosa PA. GuaA and GuaB are essential for Borrelia burgdorferi survival in the tick-mouse infection cycle. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:6231–41. doi: 10.1128/JB.00450-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo BP, Norris SJ, Rosenberg LC, Höök M. Adherence of Borrelia burgdorferi to the proteoglycan decorin. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3467–72. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3467-3472.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brown EL, Wooten RM, Johnson BJ, Iozzo RV, Smith A, Dolan MC, et al. Resistance to Lyme disease in decorin-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:845–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI11692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang XF, Pal U, Alani SM, Fikrig E, Norgard MV. Essential role for OspA/B in the life cycle of the Lyme disease spirochete. J Exp Med. 2004;199:641–8. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lovegrove FE, Peña-Castillo L, Mohammad N, Liles WC, Hughes TR, Kain KC. Simultaneous host and parasite expression profiling identifies tissue-specific transcriptional programs associated with susceptibility or resistance to experimental cerebral malaria. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:295. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Westermann AJ, Gorski SA, Vogel J. Dual RNA-seq of pathogen and host. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:618–30. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]