Abstract

Authentic Ativisha (Aconitum heterophyllum) is a rare, endangered Himalayan species. Ayurveda classical texts of c. 15th–16th century, introduced “abhava-pratinidhi dravya” concept, wherein Ativisha was categorized as an abhava dravya (unavailable drug) and Musta (Cyperus rotundus) was suggested as a pratinidhi dravya (substitute) for it. C. rotundus is a weed, abundantly available pan-India. Cryptocoryne spiralis (Naattu Athividayam) and Cyperus scariosus (Nagarmotha) are also traded as Ativisha and Musta, respectively. Yet, there are no scientific studies to validate the use of substitutes. A. heterophyllum bears no similarity in terms of botanical classification with the other candidates. This article reviews published literature with an emphasis to look for similar phytochemicals or groups of phytochemicals in the species that could contribute to similar pharmacological activities, thereby supporting the drug substitution from a bio-medical perspective. Alkaloids like atisine were found to be the main focus of studies on A. heterophyllum, whereas for the Cyperus spp., it was terpenoids like cyperene. Although alkaloids and terpenoids were reported from both species, alkaloids in C. rotundus and terpenoids in A. heterophyllum were minor constituents. Reports on phytochemicals on Cryptocoryne spiralis and C. scariosus were very limited. Despite no significant similarities in chemical profiles reported, the dravyaguna (Ayurvedic drug classification) of Ativisha and Musta was quite similar warranting further exploration into the bio-functional aspects of the drug materials.

Keywords: Aconitum, Ativisha, Ayurveda, Cryptocoryne, Cyperus, Musta, phytochemistry

INTRODUCTION

The concept of drug substitution is well-known in allopathy and resorted to when the patient develops resistance to a particular drug or suffers from undesirable side effects from its use. In Ayurveda, single, pure compounds are seldom used, and the bulk of its medicines are derived from plants. Instances of drug resistance and side effects are rare or may be not recorded in Ayurveda. However, the concept of drug substitution has been in vogue in Ayurveda and documented in texts dating to 15th and 16th centuries. Such a concept is called as “abhava-pratinidhi dravya”, wherein an “abhava dravya” (unavailable drug) is replaced by a “pratinidhi dravya” (substitute drug).[1,2,3] Neither the process of substitute identification nor reasons for using substitutes are available in the classical Ayurvedic texts. Hence, for scientists in contemporary times the substitution seems nonscientific and inappropriate, raising questions about the validity of their use in treatment. It is possible that unavailability of the original drug due to geographical and/or seasonal variations led to its substitution. Loss of biodiversity and habitat due to over-exploitation and expanding human population may also have pushed several species to near extinction.

A careful examination of Ayurvedic texts in the context of abhava-pratinidhi dravya enables us to understand the progression in the systematization of Ayurvedic knowledge. The brhattrayis (three classical texts of Ayurveda: Charaka and Sushrutha samhitas and Ashtanga Sangraha) do not use the abhava-pratinidhi dravya nomenclature. This usage occurs for the first time in Bhavaprakasha (c. 16th century AD) and has been repeated in subsequent Ayurvedic literature.

Ayurvedic medicines are characterized based upon the principles of dravyaguna vijnana. In essence, each drug is identified/characterized using its rasapanchaka attributes of rasa (taste), guna (properties), veerya (potency), vipaka (taste after digestion) and prabhava (unique action) and karma (pharmacological action).[1] Using this concept, it may be possible to explain the logic underlying the choice of abhava-pratinidhi dravya drug pairs.

More than 150 “abhava-pratinidhi dravya” pairs are mentioned in the Ayurvedic texts. Reasons for some of the substitutes suggested are simple: E.g. Kusta (Saussurea lappa C.B. Clark) as a substitute for Pushkaramula (Inula racemosa Hook.f.),[2] where the species are morphologically similar (both belong to the Asteraceae family) and have chemical resemblances as well (both have constituents containing the biologically significant α-methylene γ-lactone functionality).[4] However, there are also instances where the substitutes show no similarities either in morphology or chemical constituents with the original drug. E.g., substitution of the wood of Rakthachandana (Pterocarpus santalinus L.) with the root of Ushira (Vetiveria zizanioides L.) for use in Pitta dominated diseases.[2] P. santalinus is rich in phenolics and flavonoids,[5] whereas terpenoids are the major constituents present in V. zizanioides.[6] In these examples, comparing the dravyaguna vijnana may prove to be useful.

Musta (pratinidhi dravya) is mentioned in Ayurveda as a substitute for Ativisha (abhava dravya) and they are strikingly different botanical entities.[2,3] The Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India (API) identifies Ativisha as Aconitum heterophyllum Wall. ex Royle (Ranunculaceae) and Musta as Cyperus rotundus L. (Cyperaceae). A. heterophyllum is a perennial herb found in the Himalayas at high altitudes from 3000 m,[4] is classified as an endangered species[7] and is in the negative list of exports of the Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India.[8] C. rotundus, on the other hand, is a common weed widely distributed throughout India.[7,9]

The main use of both Ativisha and Musta is in the treatment of diarrheal disorders as powders of dried tubers or dried rhizomes, respectively.[9,10] According to the API, the suggested dose in powder form is 0.6–2.0 g for Ativisha and 3–6 g for Musta.[11,12] This indicates that Ativisha possibly is more potent than Musta.

Although the API has identified Ativisha and Musta unequivocally as A. heterophyllum and C. rotundus respectively, Cryptocoryne spiralis (Retz.) Fisch ex Wydler is very often sold in the markets as Naattu Athividayam (Malayalam/Tamil: Local Ativisha).[9] The original Ativisha is called Athividayam in Malayalam, Tamil and Telugu.[13] While Cryptocoryne spiralis is inexpensive, freely available and has some properties similar to Ativisha, some Ayurvedic scholars do not accept it as Ativisha.[9] In the case of Musta too some confusion exists. The Ayurvedic texts mention two types of Musta, namely “Nagara Musta” and “Bhadra Musta”. The former has been identified as Cyperus scariosus R. Br., and the latter, C. rotundus. However, both species of the Cyperaceae family are traded under the name Musta.[9]

All the four species, namely A. heterophyllum, C. rotundus, C. scariosus and Cryptocoryne spiralis have been studied both phytochemically and pharmacologically. Most studies, however, are based on individual plants and are not on a comparative basis. Recent reviews on A. heterophyllum and C. rotundus cover most of the work done on these two species.[14,15,16]

This article looks at the concept of abhava-pratinidhi dravya, with a focus on phytochemical similarities/differences between a selected pair, that is, Ativisha and Musta. To make use of this unique concept, a thorough understanding of the Ayurvedic logic behind substitution as well as phytochemical and pharmacological evidence is essential. This is an attempt to put together the vast information available on the chemistry of the four species in order to unearth any possible similarities in their chemical constituents. Similar review on the pharmacology aspect of the same species has also been put together for publication elsewhere by the authors. A complete picture thus obtained could help in understanding the basis for the substitution of Ativisha by Musta. It may also throw some light on the basis of Ayurvedic ways of drug identification.

TRADE AND DISTRIBUTION

It has been estimated by Ved and Goraya that the annual consumption of Ativisha in India is around 200–500 tonnes with price varying from Rs. 2000 to 4000/kg. The same authors have given a consumption figure of 2000–5000 tonnes for Musta and a cost range of Rs. 15–30/kg.[7] No such data is available for C. scariosus and Cryptocoryne spiralis. The consumption data for Ativisha is disproportionately high when compared with the likely availability of A. heterophyllum, suggesting that what is traded as Ativisha is not exclusively A. heterophyllum. Substitution and adulteration appear to be rampant.

BOTANICAL DESCRIPTION

Aconitum heterophyllum Wall. ex Royle (Ranunculaceae – Dicotyledonae)

More than 300 species are known in the Aconitum family.[17] In China alone, there are more than 200 Aconitum species, although only Aconitum kushnezoffii Reichb., and Aconitum carmichaeli Debx. are recorded in the Chinese Pharmacopoeia 2005 edition.[18] In India, there are around 24 species, of which the major ones found in the Indian markets are A. napellus Linn., A. chasmanthum Stapf. ex. Holmes, A. ferox Wall. ex Ser., A. palmatum D.Don and A. heterophyllum Wall.ex Royle.[19]

Aconitum heterophyllum is a perennial herb found in the alpine and sub-alpine regions above 3000 m.[13,20] It flowers in the second year. The flowers are helmet-shaped, bright blue or greenish blue in color and have a purple vein. For medicinal use, the roots from plants that are 2 years old and bearing fully developed tubers are collected. The tubers sometimes occur as a pair of mother and daughter tubers [Figure 1]. In India, the plant is most commonly found in Jammu and Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh and in Uttarakhand. As it is an endangered species, the Director General of Foreign Trade prohibits the export of Aconitum species of plants, plant portions and their derivatives and extracts obtained from the wild.[8] Cultivation has been undertaken in Uttarakhand as a resource augmentation effort.[20]

Figure 1.

Aconitum heterophyllum Wall. ex Royle: Habit and tubers

Cyperus rotundus L. (Cyperaceae - Monocotyledonae)

Cyperus rotundus, also known as purple nutsedge or nutgrass, is a common weed found all over India in fields, agricultural land, and moist waste land.[13] It is a tufted, grass-like perennial plant, whose stem is three angled at the top with brown spikelets. Inflorescences are small, consisting of tiny flowers with a red-brown husk. Tubers are 3–20 mm in diameter, rust-colored turning black with a characteristic odor [Figure 2]. The rhizomes from 2-year-old plants are used for medicinal purposes.

Figure 2.

Cyperus rotundus L.: Habit and rhizomes

Cyperus scariosu s R.Br. (Cyperaceae - Monocotyledonae)

Cyperus scariosus is a perennial herb with a creeping rhizome up to 5 cm long. Stems are slender and rounded, but 3-angular in the upper part [Figure 3]. There are utmost 3 short leaves. It is a coastal species found in swampy, brackish localities.[21]

Figure 3.

Cyperus scariosus R. Br.: Habit and tubers

Cryptocoryne spiralis (Retz.) Fisch.ex Wydler (Araceae - Monocotyledonae)

Cryptocoryne spiralis, also known as Naattu Athividayam, is a perennial herb found in seasonally inundated places along rivers, roadside ditches and wet sandy places along the coast.[21,22,23] Corms are up to 1 cm thick and up to 30 cm long. Leaves are erect or spreading with green petioles and elongate-elliptical to linear leaf blades [Figure 4]. It is a plant popularly used in aquariums.

Figure 4.

Cryptocoryne spiralis (Retz.) Fisch ex Wydler: Rhizomes

PHYTOCHEMISTRY

In this section, the published literature on A. heterophyllum and C. rotundus, the substitute as per Ayurveda and their market substitutes (viz. C. rotundus, Cryptocoryne spiralis and C. scariosus) have been reviewed. This is with the aim of looking for similarities between them in terms of phytoconstituents and groups of phytochemicals.

Aconitum heterophyllum

Phytoconstituents of Aconitum species

The main alkaloid reported in Aconitum is aconitine that is highly toxic. In mice, the oral LD50 is < 2 mg/kg.[24] However, unlike the other Aconitum species which have aconitine as the major alkaloid, atisine is the main alkaloid in A. heterophyllum.[25] It is comparatively nontoxic in nature, making A. heterophyllum a safer herb to use when compared with other Aconitum species such as A. ferox.[9] In Ayurvedic practice, the tuber of A. ferox (Vatsanabhi) undergoes a thorough process of purification (shodhana) before being used as a drug,[26] whereas no such process is mandatory for A. heterophyllum.

Alkaloids of Aconitum heterophyllum

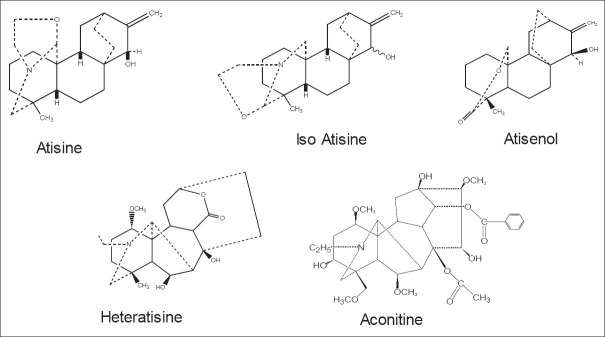

Jowett has documented the early investigations on the tubers of A. heterophyllum, beginning with Broughton (1873), Wasowicz (1879) and Wright (1879).[27] Broughton was first to isolate atisine. Different salts (sulphate, hydrochloride and platinichloride) were prepared from the alkaloid, and the molecular formula was deduced. Wasowicz showed that the aconitic acid is also present along with atisine. He suggested slight modifications in the molecular formula of atisine. Wright proposed a new formula for atisine based on analysis of its aurichloride salt [Figure 5]. Subsequently, Jowett investigated the properties and composition of atisine and its salts in great detail. They did not find any alkaloid other than atisine.[27] Jacob and Craig in 1942–1943 confirmed the structure of atisine and also isolationed three other alkaloids hetisine, heteratisine and benzoylheteratisine.[28,29]

Figure 5.

Important chemical constituents of Aconitum heterophyllum

Detailed studies by Pelletier on hetisine[30] atisine and heteratisine[31,32,33] in the years 1962–1964 helped in their structure elucidation. Further investigations on A. heterophyllum in 1967–1968 by Pelletier et al. led to the isolation and structure elucidation of additional new diterpene alkaloids: Atidine, F-dihydroatisine, hetidine and hetisone as well as lactone alkaloids heterophyllisine, heterophylline and heterophyllidine.[34,35] In 1982, a new entatisene diterpenoid lactone, atisenol, was isolated from the tuber.[36] Dvornik and Edwards in 1963 established the structure and more importantly, the stereochemistry of atisine and related alkaloids.[37]

Work on Aconitum alkaloids by Ahmad et al. in 2008 led to the isolation of two new aconitine-type norditerpenoid alkaloids 6-dehydroacetylsepaconitine and 13-hydroxylappaconitine along with known norditerpenoid alkaloids lycoctonine, delphatine and lappaconitine.[38]

Although aconitine, which is the major alkaloid of the other Aconitum species, is not a major constituent of A. heterophyllum, high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) studies carried out on the tubers from Kumaon and Garhwal regions of the Himalayas showed that it is present in different populations and varies from 0.13% to 0.75%(dry weight basis).[39,40] Bahuguna and others reported higher content of atisine (0.35%) and aconitine (0.27%) in green house grown A. hetrophyllum when compared with the naturally grown plants (0.19% and 0.16%, respectively).[41] Similar HPLC studies on the quantification of aconitine from tubers of A. heterophyllum from the Kashmir valley have reported 0.0014–0.0018% aconitine.[42] From the reported literature, it is evident that, alkaloids were the main focus of study in A. heterophyllum. Several pharmacological actions of Ativisha have been attributed to their alkaloids.[24]

Cyperus rotundus

Terpenes

At least two exhaustive review articles listing out the different constituents and the pharmacological activities have been published on this species.[15,16] Most of the studies on the rhizomes of C. rotundus are on essential oils.

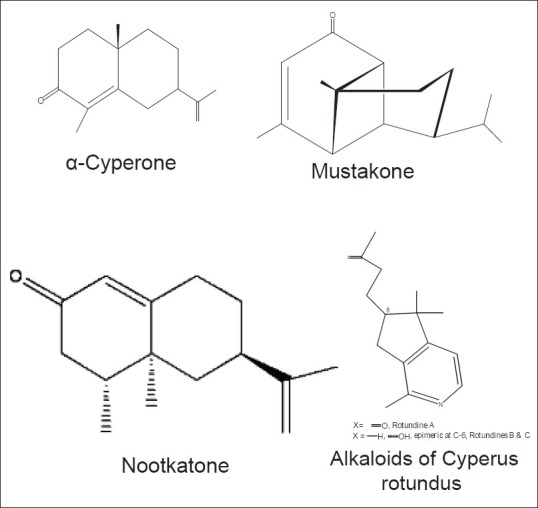

In 1964, while studying the composition of the essential oils, Trivedi et al. isolated a new sesquiterpene, cyperene, which is a tricyclic hydrocarbon. Earlier work by them had also confirmed the presence of β-selinene.[43] Around the same time, Kapadia et al. isolated a new ketone, which was named mustakone, after a local name for C. rotundus, Mustaka. They also achieved a direct conversion of copaene to mustakone, further confirming the structures for both.[44] Additional studies by the group in 1967 described in detail the structures of copadiene (a conjugated diene), epoxyguaiene (an epoxide), rotundone and cyperolone (a hydroxy ketone) - all found in C. rotundus.[45]

Paknikar et al. in 1977 reported the isolation and structure elucidation of the sesquiterpenoids rotundene and rotundenol.[46]

Singh and Singh in 1980 isolated from the benzene extract of C. rotundus the triterpenoid acid oleanolic acid and its glycoside. The glycoside, on acid hydrolysis, produced glucose and rhamnose. This glycoside, oleanolic acid-3-O-neohesperidoside, had not been isolated previously from any plant source.[47]

Dhillon et al. in 1993 were the first to report the presence of caryophyllene in C. rotundus.[48]

The rhizomes of C. rotundus have been used in Thailand as an antimalarial. Thebtaranonth et al. in 1995 isolated the constituents responsible for its antimalarial activity: Patchoulenone, caryophyllene alpha-oxide, 4, 7-dimethyl-1-tetralone and a novel sesquiterpene endoperoxide 10, 12-peroxycalamenene of which the endoperoxide (containing peroxide oxygen atoms) showed the strongest antimalarial effect with an EC50 of 2.33 × 10-6 M.[49] The peroxide linkage is a known antimalarial pharamcophore.[50]

Ohira et al. characterized three new sesquiterpenoids from C. rotundus. Two of the newly isolated oils had 4, 5-secoeudesmane skeletons and were identified as 2α-(5-oxopentyl)-2 β-methyl-5 β-isopropenyl cyclohexanone and 2 β-(5-oxopentyl)-2 β-methyl-5 β-isopropenyl cyclohexanone. The third oil isolated had a cyperolone carbon skeleton and was characterized as a tetracyclic acetal.[51]

Analysis of the essential oil of C. rotundus by GC and GC-MS in 2001 by Sonwa and König enabled positive identification of a number of constituents.[52]

Work was done on optimization of the method of extraction of essential oils from the tubers of C. rotundus by CU Tam et al. in 2006. It was observed that the three methods investigated-hydro distillation, pressurized liquid extraction and supercritical fluid extraction-showed differences in the contents of the main volatile components studied.[53] In a recent development, Korean scientists isolated two new patchoulane type sesquiterpenes and three known patchoulane and two eudesmane types from the rhizomes of C. rotundus.[54] The rhizomes also afforded on extraction two new sesquiterpenoids with rearranged secoeudesmane and germacrane skeletons, a new 9, 10-seco-cycloartane triterpenoid as well known compounds comprising a monoterpenoid, five sesquiterpenoids and a nortriterpenoid.[55]

Phenolics and flavonoids

Nagulendran et al. in 2007 estimated the total phenolic content in the ethanol extract of dried rhizome to be 73.27 ± 4.26 g/100 g extract in terms of catechin equivalents.[56]

Many phenolics and flavonoids have been isolated from C. rotundus. Samariya and Sarin obtained four known flavonoids, quercetin, kaempferol, catechin and myrcetin from the leaves and roots of the plant.[57] A new flavanone, 7, 8-dihydroxy - 5,6 - methylenedioxyflavone as well as five known compounds, namely quercetin, kaempferol, luteolin, ginkgetin and isoginkgetin were isolated from the rhizomes.[58] The rhizomes are also the source of two new phenolics, 1alpha-methoxy -3beta - hydroxy-4alpha (3′,4′-dihydroxyphenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthalene and its demethylated parent.[59]

Ito et al. isolated several stilbene oligomers from C. rotundus. They are (+) and (−)-E-cyperusphenol A, E-mesocyperusphenol A, cyperusphenol B as well as the known cyperusphenols C and D, scirpusins A and B, piceid and luteolin.[60]

Glycosides

The rhizomes of C. rotundus were shown to contain two new iridoid glycosides, rotundusides A and B.[61,62] Methanolic extract of the rhizomes of C. rotundus gave a keto-alcohol characterized as 21-oxo-n-tricontanol and two new triterpenoid glycosides, 18-epi-alpha-amyrin glucuronoside and oleanolic acid arabinoside besides the known compounds alpha and beta amyrin glucopyranosides.[63]

Analysis of different extracts (aqueous, total oligomers flavanoids, essential oil, ethyl acetate and methanol) of the tubers was carried out by Kilani et al. in 2007. Tannins, flavanoids and coumarins were found to be present in all the extracts. Composition of the essential oil was investigated by GC and GC-MS and around 70 sesquiterpene hydrocarbons were identified along with oxygenated sesquiterpenes and a few monoterpene hydrocarbons.[64]

Study of the rhizomes of C. rotundus in 2008 led to the isolation and structure elucidation of a novel norsesquiterpene norcyperone.[65] Xu et al. in 2009 isolated 2 new compounds-epiguaidiol A and sugebiol-along with four known sesquiterpenes guaidiol, sugetriol triacetate, cyperenoic acid and cyperotundone.[66] Klahn et al. reported in 2012, the total synthesis of cyperolone, a sesquiterpenoid found in C. rotundus, starting from carvone.[67]

Interest in the discovery of new secondary metabolites in traditional Chinese Medicines led to the work by Yang and Shi in 2012 on the rhizomes of C. rotundus. They investigated the ethanolic extract of the dried and powdered rhizomes of C. rotundus that were further partitioned with petroleum ether. They succeeded in isolating two new sesquiterpenoids – rotundusolide A and B having secoeudesmane sesquiterpenoids skeleton as well as a new triterpenoid rotundusolide C.[55]

Alkaloids of Cyperus rotundus

In 2000, Jeong et al., in their search for alkaloids from medicinal plants, isolated 3 sesquiterpene alkaloids from the rhizomes of C. rotundus. Rotundines A-C. This was the first report on the presence of alkaloids in this plant. This was also the first time that such sesquiterpene alkaloids with a cyclopenta pyridine structure were isolated from natural sources. These alkaloids were colorless oils and gave a positive reaction to Dragendorff's reagent. However, the quantities obtained were very small (in the range of 0.7–1.1 ppm).[68] Adams et al. reported a complex mixture of terpenoids and alkaloids as well as condensed tannins in the rhizomes of C. rotundus, using histochemical studies.[23]

Studies on chemotypes of Cyperus rotundus

It is not surprising that such a widely distributed species like C. rotundus has four major chemotypes. These have been classified as H, K, M and O, based upon the composition of the essential oils. H, M and O chemotypes are found in Asia, with O being the most widely distributed. K is reported to be the dominant type in the Hawaiian islands.[69]

Studies carried out on the composition of essential oils of C. rotundus from two regions in South Africa support the conclusions of the above data and show that there is a compositional difference between C. rotundus found in South Africa and the rest of the world.[70] Similarly, Ghannadi et al. in 2012 carried out the phytochemical screening and essential oil analysis of C. rotundus from Iran. The phytochemical screening revealed the presence of flavanoids, tannins, alkaloids and essential oils. The essential oil analysis was carried out by GC-MS. The major constituents were cyperene, caryophyllene and α-longipinane. These results also showed differences from the analysis done by earlier investigators from other parts of the world.[71]

Within India, the composition of the essential oil of C. rotundus shows a geographical variation. Jirovetz et al. showed in 2004 that the composition of the essential oils of C. rotundus from South India is dominated by the presence of α-copaene (11.4%), valerenal (9.8%), caryophyllene oxide (9.7%), cyperene (8.4%), nootkatone (6.7%), and trans-pinocarveol (5.2%). GC-FID and GC-MS analysis were carried out to identify the constituents and olfactoric evaluations were also done to correlate the aroma attributes with the compounds responsible for the aroma.[72] A similar GC-MS study on the essential oils of C. rotundus from Dehradun showed that the major components were 5-oxo-isolongifolene (16.27%), α-gurjunene (10.22%), valerenyl acetate 8.88%) α-salinene (4.48%), valerenic acid (3.67%) and γ-cadinene (3.4%).[73]

From the above, it is clear that, terpenoids are the major phytoconstituents in C. rotundus. Phenolics and flavonoids are also present and there is only one report on the occurrence of alkaloids in this species.

Cyperus scariosus

When compared to C. rotundus, little information is available on the chemical constituents of C. scariosus. The essential oil was shown to contain mainly bicyclic and tricyclic sesquiterpenes.[74] In 1957 Dhingra and Dhingra established that the essential oil of C. scariosus contains a bicyclic ketone, a tricyclic tertiary alcohol and a tricyclic sesquiterpene hydrocarbon.[75] Nerali et al. in 1965 reported the isolation of a new sesquiterpene ketone from C. scariosus, which they called isopatchoulenone, due to its structural similarity to patchoulenone.[76] In the same year, Nigam isolated a sesquiterpene ketone, which he called cyperenone, from the same species.[77] Similarly, Hikino et al., in 1967, also isolated a sesquiterpene ketone from the three species of the Cyperus genus (C. rotundus, C. scariosus and C. articulatus) which they named cyperotundone.[78] Neville et al. in 1968 also isolated a ketone and established by spectral data that the ketones isolated by the earlier investigators were one and the same and proposed a new name, isopatchoul-4 (5)-en-3-one.[79] Nerali et al. in 1967 isolated two sesquiterpene alcohols from the alcoholic fractions of the essential oils of the tubers. These were named cyperenol and patchoulenol.[80] Other sesquiterpenes isolated from C. scariosus include rotundene and rotundenol,[46,81] the known hydrocarbon (-)-beta-selinene and the new compound isopatchoula-3,5-diene.[82] Uppal, along with Chhabra et al., while studying the species for plant growth regulators, isolated a new hydrocarbon, isopatchoul-3-ene. This compound was subjected to spectral characterization and found to be a tricyclic compound with an isopatchoulane type carbon skeleton.[83]

The essential oil derived from rhizomes of C. scariosus grown in Bangladesh was analysed by GC-MS and as many as 31 compounds were identified.[84] A similar analysis of the essential oil from fresh tubers of C. scariosus collected in central india showed the presence of 30 compounds.[85]

Bhatt et al. in 1981 studied the phytoconstituents of the leaves of C. scariosus and isolated a phenolic glycoside, which on acidic hydrolysis gave an aglycone along with glucose and rhamnose. The aglycone was identified as leptosidin and the structure of the new glycoside was assigned as leptosidin 6-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-O-α-L-rhamnopyranoside.[86] The leaves were also the source of two more glycosides, leptosidin-6-O-[β-D-xylopyranosyl (14)-β-D-arabinoside[87] and stigmasta-5, 24 (28)-diene-3 β-O-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-O-β-D-aabinopyranoside.[88]

Sahu et al. in 2010 isolated from the tubers of C. scariosus a new compound, namely 2, 3-diacetoxy-19-hydroxy-urs-12-ene-24-O-β-D-xylopyranoside.[89] The presence of alkaloid-terpenoid complex in the rhizomes of C. scariosus by histochemical studies was reported by Adams et al. in 2013. However, the occurrence of this complex is not as extensive when compared to C. rotundus.[23]

Cryptocoryne spiralis

As mentioned earlier, Cryptocoryne spiralis is known in Tamil Nadu as “naattu adhividayam” and sold in the markets in the place of A. heterophyllum. It is also known as “Indian Ipecacuanha.”[90] While the actual Ipecacuanha root (Radix ipecacuanha) found mainly in Brazil, contains the alkaloids emetine and cepheline, these are absent in the Indian variety.[91]

Gupta et al. in 1983 isolated 4 compounds, including 2 new oxo fatty acid esters, ethyl 14-oxotetracosanoate and 15-oxoeicosanyl 14-oxoheptadecanoate from the hexane extract of the corms.[92] Further studies in 1984 led to the isolation of two new fatty acids, 22-oxononacosanoic acid and 26-oxohentriacontanoic acid.[93] Two steryl esters from the same plant, 5α-stigmast-11-en-3 β-yl palmitate and 24-ethyl-5α-cholesta-8 (14), 25-dien-3 β-yl stearate were also isolated.[94]

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Aconitum heterophyllum is an endangered species available only at high altitudes; while C. rotundus, C. scariosus and Cryptocoryne spiralis are widely available. Although in all four species, the tuber/rhizomes are used, the similarity ends there. While C. rotundus and C. scariosus belong to the Cyperaceae family, Cryptocoryne spiralis belongs to the Araceae family and A. heterophyllum belongs to Ranunculaceae family. The former three are monocots while A. heterophyllum is a dicot. The four species also differ in their habitat.[23]

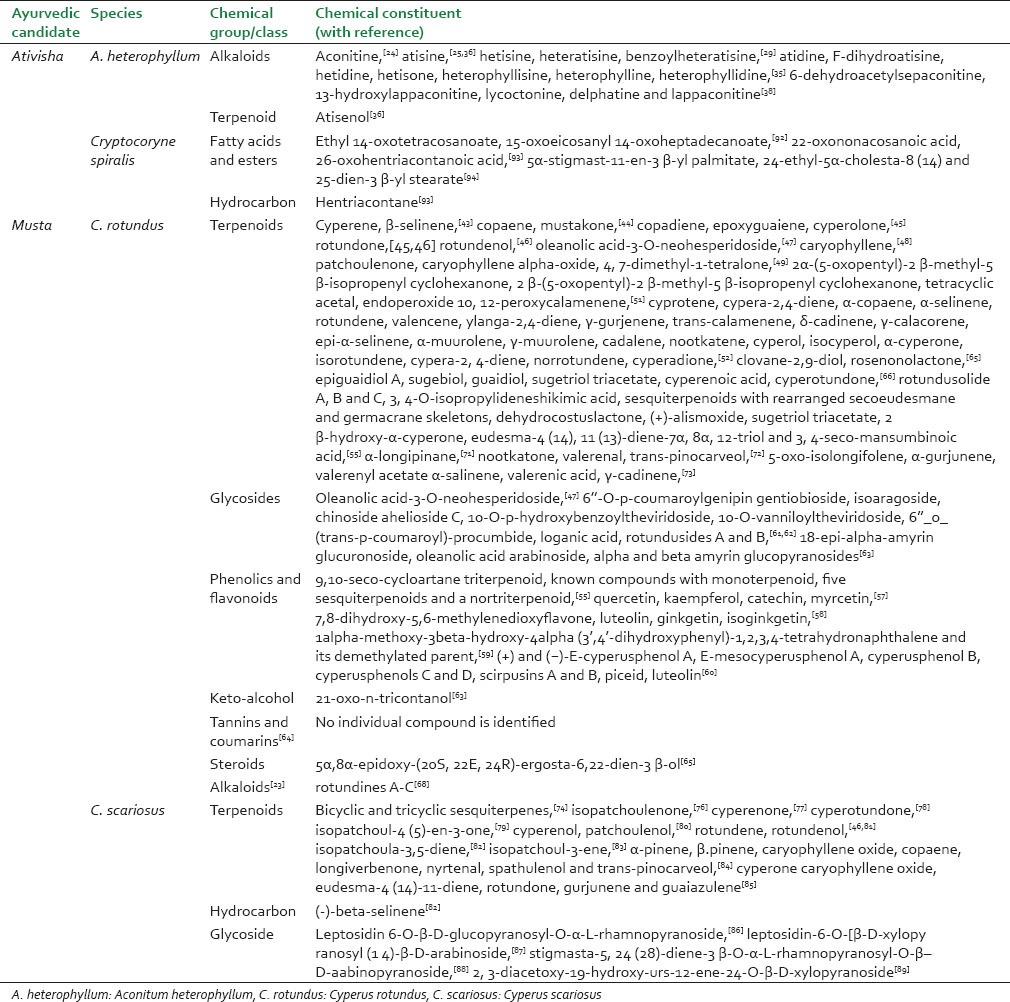

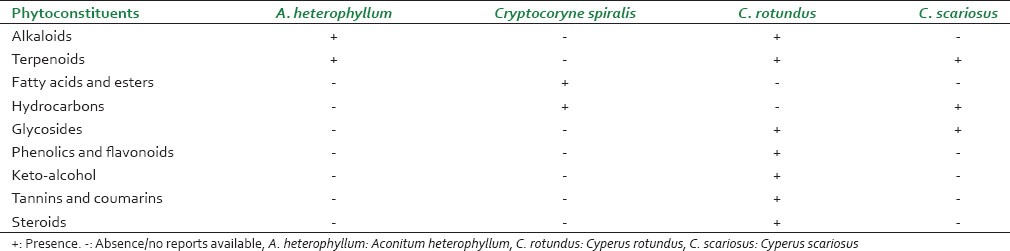

The phytochemistry of A. heterophyllum, C. rotundus, C. scariosus and Cryptocoryne spiralis is summarized in Tables 1 and 2. As per published reports, no significant similarity in chemical composition was apparent between A. heterophyllum and C. rotundus. However, alkaloids and terpenoids were common classes of compounds reported as being present in both species, nevertheless only as minor constituents in C. rotundus and A. heterophyllum respectively. Alkaloids of A. heterophyllum and essential oils of C. rotundus have been studied extensively. Except for the lone report by Jeong et al. on the presence of alkaloids (Rotundines A-C)[68] [Figure 6], no other alkaloids have been reported as detected in C. rotundus. Furthermore, the extensive worldwide studies on essential oils of C. rotundus have shown that there is a lot of chemical diversity within the species. A recent review of the phytochemistry and pharmacology of C. rotundus by Sivapalan stresses on the need for further exploration of various pharmacological uses of this herb because of this chemical diversity.[95] Studies carried out on C. scariosus and Cryptocoryne spiralis are few and far between and do not mention the presence of alkaloids.

Table 1.

Ativisha and Musta species with reported phytoconstituents

Table 2.

Comparison of Ativisha-Musta species based on reported phytoconstituent classes

Figure 6.

Important chemical constituents of Cyperus rotundus

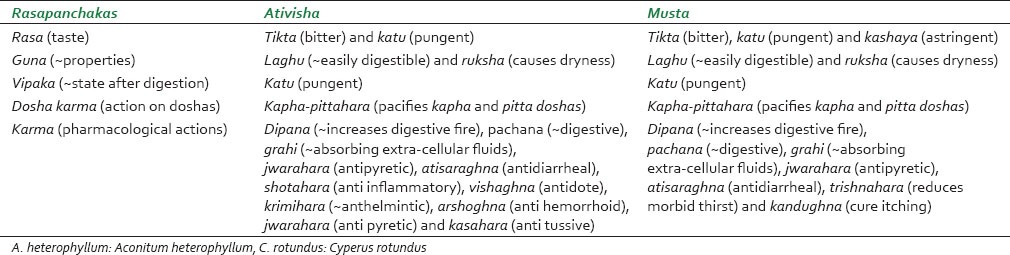

As per Ayurveda, dravyas (materials) are characterized based upon dravyaguna vijnana, where elements of rasapanchaka (taste, properties, potency, postdigestive effect and action) are considered. Dravyaguna way of characterization of plants is different from modern botanical or chemo-taxonomical ways of characterizing herbal drugs. E.g., Charaka samhita describes Panchashat Mahakashaya (fifty therapeutical groups of medicinal herbs) classifying herbal drugs according to their pharmacological actions.[10] It is interesting to note that despite lack of apparent similarities in botanical aspects as well as chemical composition, the rasapanchakas of Ativisha and Musta were similar [Table 3]. Both of them have bitter and pungent taste, cause dryness in the body, are easily digestible, retain pungency even after digestion and pacify kapha and pitta doshas. They are prescribed to increase digestive fire, to prevent fluid loss from the body and to control pyrexia and diarrhea. However, their virya (potency) are different. Ativisha has a hot potency (usna), while Musta is cold (shita). These facts enable us to conclude that the substitution of Musta (pratinidhi dravya) for Ativisha (abhava dravya) is most likely based on dravyaguna. Probably Ayurvedic seers looked at the similarities at rasapanchaka and karma levels of abhava-pratinidhi dravyas, rather than their morphological similarity.

Table 3.

Rasapanchaka of Ativisha and Musta

It has to be borne in mind that the phytochemical studies published in the literature have not been done with a purpose of comparing the species. Dedicated scientific studies of Ativisha and Musta as well as other abhava-pratinidhi drug pairs are warranted to understand this concept better. In conclusion, understanding the concept of dravyaguna vijnana is essential to understand the logic behind selection of substitutes mentioned in Ayurveda. This in turn will be useful in identifying new substitutes, especially for drugs that are unavailable for use since they are endangered, seasonal, regional or expensive.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Mr. DK Ved, Dr. GS Goraya, Prof. KV Krishnamurthy, Dr. K Ravikumar, Dr. K Haridasan and Mr. MV Sumanth for botanical details and authentic collections. Thanks are due to Dr. K Ravikumar and Dr. Noorunnisa Begum S for the plant images. This project was funded by the Centre of Excellence, Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MoEF), Government of India, which is gratefully acknowledged. Subrahmanya Kumar K acknowledges affiliation by Manipal University, for his PhD research on the topic of abhava pratinidhi dravya and ETC-CAPTURED, the Netherlands for fellowship.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Centre of Excellence, Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MoEF), Govt. of India.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chunekar KC. 1st ed. Varanasi: Chaukhambha Bharati Academy; 2004. Bhavaprakasa Nighantu of Sri Bhavamisra; p. 63. 127-8, 243-4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shastry L. 7th ed. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Sanskrit Sansthan; 2002. Yogaratnakara, with Vidyotini Hindi commentary; p. 171. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mishra SN. 1st ed. Varanasi: Chaukhamba Surbharti Prakashan; 2007. Bhaishajyaratnavali of Kaviraj Govind Das Sen; pp. 80–2. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta AK, Tandon N, Sharma M. New Delhi: Indian Council of Medicinal Research; 2006. Quality Standards of Indian Medicinal Plants; p. 1. 89, 169, 204. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arunakumara KK, Walpola BC, Subasinghe S, Yoon M. Pterocarpus santalinus Linn. f.(Rath handun): A review of its botany, uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. J Korean Soc Appl Biol Chem. 2011;54:495–500. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhushan B, Kumar SS, Singh T, Singh L, Hema A. Vetiveria zizanioides (Linn.) Nash: A Pharmacological review. Int Res J Pharm. 2013;4:18–20. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ved DK, Goraya GS. Dehradun: Bishen Singh Mahendrapal Singh and Bangalore: FRLHT; 2008. Demand and Supply of Medicinal Plants in India; p. 125. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zoo rules 1992 notification. [Last cited on 2014 Apr 01]. Available from: http://www.envfor.nic.in/legis/wildlife/wildlife9.html .

- 9.Sastry JL. 2nd ed. II. Varanasi: Chaukhambha Orientalia; 2005. Dravyaguna Vijnana; pp. 23–32. (551-7). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sastri K. 5th ed. I. Varanasi: Chaukhambha Sanskrit Sansthan; 1997. Caraka Samhita of Agnivesa, Sootrasthana. [Google Scholar]

- 11.1st ed. I. New Delhi: Government of India, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Department of Indian Systems of Medicine and Homoeopathy; 2001. Anonymous. The Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India. Part-I; pp. 22–3. [Google Scholar]

- 12.1st ed. Vol. 3. New Delhi: Government of India, Ministry of health and family welfare, Department of Indian Systems of Medicine and Homoeopathy; 2001. Anonymous. The Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India. Part-I; pp. 129–30. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarin YK. Dehradun: Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh; 2008. Principal Crude Herbal Drugs of India: An Illustrated Guide to Important, Largely Used and Traded Medicinal Raw Materials of Plant Origin; p. 28. 222. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srivastava N, Sharma V, Kamal B, Dobriyal AK, Singh Jado V. Advancement in research on Aconitum sp.(Ranunculaceae) under different area: A review. Biotechnology. 2010;9:411–27. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meena AK, Yadav AK, Niranjan US, Singh B, Nagariya AK, Verma M. Review on Cyperus rotundus-A potential herb. Int J Pharm Clin Res. 2010;2:20–2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chandratre RS, Chandarana SS, Trivedi MN, Joshi TA, Nehete MN. Cyperus rotundus: Traditional uses and pharmacological actions: A review. Inventi Rapid Planta Activa ; 2011:4. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Been A. Aconitum: Genus of powerful and sensational plants. Pharm Hist. 1992;34:35–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singhuber J, Zhu M, Prinz S, Kopp B. Aconitum in traditional Chinese medicine: A valuable drug or an unpredictable risk? J Ethnopharmacol. 2009;126:18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chopra RN, Chopra IC. Kolkata: Academic Publishers; 2006. Chopra's Indigenous Drugs of India; pp. 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nautiyal MC, Nautiyal BP. Dehra Dun: Bishen Singh Mahendra Pal Singh; 2004. Agrotechniques for High Altitude Medicinal and Aromatic Plants; p. 30. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cook CD. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1996. Aquatic and Wetland Plants of India; p. 57. 124. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anandakumar A, Rajendran V, Thirugnanasambantham MP, Balasubramanian M, Muralidharan R. The pharmacognosy of nattu atividayam-The corms of Cryptocoryne spiralis fisch. Anc Sci Life. 1982;1:200–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams JS, Kuruvilla GR, Krishnamurthy KV, Nagarajan M, Venkatasubramanian P. Pharmacognostic and phytochemical studies on ayurvedic drugs Ativisha and Musta. Braz J Pharm. 2013;23:398–409. [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Neil MJ, Smith A, Hecklman PE, Obenchain JR, Gallipeau JAR, D’Arecca MA. 13th ed. New Jersy: Merck and Co. Inc; 2001. The Merck Index; p. 118. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chatterjee A, Prakash SC. New Delhi: Vedams Books International; Treatise on Indian Medicinal Plants; p. 1. 111-21. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reddy KR. 1st ed. Varanasi: Chaukhambha Sanskrit Bhavan; 2005. Bhaishajya Kalpana Vijnanam; p. 535. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jowett HA. Contributions to our knowledge of the aconite alkaloids. Part XIII. On atisine, the alkaloid of Aconitum heterophyllum. XCIX. J Chem Soc Trans. 1896;69:1518–26. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jacobs WA, Craig LC. The aconite alkaloids VIII. On atisine. J Biol Chem. 1942;143:589–603. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobs WA, Craig LC. The aconite alkaloids Ix. The isolation of two new alkaloids from Aconitum heterophyllum, heteratisine and hetisine. J Biol Chem. 1942;143:605–9. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solo AJ, Pelletier SW. Aconite alkaloids, the structure of hetisine. J Org Chem. 1962;27:2702–3. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aneja R, Locke DM, Pelletier SW. Diterpene alkaloids. Structure and stereochemistry of heteratisine. Tetrahedron. 1973;29:3297–08. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aneja R, Pelletier SW. Diterpene alkaloids. Structure of heteratisine. Tetrahedron Lett. 1964;5:669–77. doi: 10.1016/s0040-4039(01)99596-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pelletier SW, Parthasarathy PC. The diterpene alkaloids. Further studies of atisine chemistry. J Am Chem Soc. 1965;87:777–98. doi: 10.1021/ja01082a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pelletier SW, Aneja R. The diterpene alkaloids. Three new diterpene lactone alkaloids from Aconitum heterophyllum wall. Tetrahedron Lett. 1967;6:557–62. doi: 10.1016/s0040-4039(00)90547-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pelletier SW, Aneja R, Gopinath KW. The alkaloids of Aconitum heterophyllum wall: Isolation and characterization. Phytochemistry. 1968;7:625–35. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pelletier SW, Ateya AM, Finer-Moore J, Mody NV, Schramm LC. Atisenol, a new ent-atisene diterpenoid lactone from Aconitum heterophyllum. J Nat Prod. 1982;45:779–81. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dvornik D, Edwards OE. The structure and stereochemistry of atisine. Can J Chem. 1964;42:137–49. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ahmad M, Ahmad W, Ahmad M, Zeeshan M, Obaidullah, Shaheen F. Norditerpenoid alkaloids from the roots of Aconitum heterophyllum Wall with antibacterial activity. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2008;23:1018–22. doi: 10.1080/14756360701810140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pandey H, Nandi SK, Kumar A, Agnihotri RK, Palni LM. Acontine alkaloids from the yubers of Aconitum heterophyllum and A. balfourii: Critically endangered medicinal herbs of Indian central Himalaya. Natl Acad Sci Lett. 2008;31:89–93. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bahuguna R, Purohit MC, Rawat MS, Purohit AN. Qualitative and quantitative variations in alkaloids of Aconitum species from Gharwal Himalaya. J Plant Biol. 2000;27:179–83. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bahuguna R, Prakash V, Bisht H. Quantitative enhancement of active content and biomass of two Aconitum species through suitable cultivation technology. Int J Conserv Sci. 2013;4:101–6. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jabeen N, Rehman S, Bhat KA, Khuroo MA, Shawl AS. Quantitative determination of aconitine in Aconitum chasmanthum and Aconitum heterophyllum from Kashmir Himalayas using HPLC. J Pharm Res. 2011;4:2471–3. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trivedi B, Motl O, Smolikova J, Sorm F. Structure of the sesquiterpenic hydrocarbon cyperene. Tetrahedron Lett. 1964;5:1197–201. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kapadia VH, Nagasampagi BA, Naik VG, Dev S. Studies in sesquiterpenes - XXII structure of mustakone and copaene. Tetrahedron. 1965;21:607–18. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kapadia VH, Naik VG, Wadia MS, Dev S. Sesquiterpenoids from the essential oil of C. rotundus. Tetrahedron Lett. 1967;8:4661–7. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paknikar SK, Motl O, Chakravarti KK. Structures of rotundene and rotundenol. Tetrahedron Lett. 1977:2121–4. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh PN, Singh SB. A new Saponin from mature tubers of Cyperus rotundus. Phytochemistry. 1980;19:2056. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dhillon RS, Singh S, Kundra S, Basra AS. Studies on the chemical composition and biological activity of essential oil from Cyperus rotundus Linn. Plant Growth Regul. 1993;13:89–93. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thebtaranonth C, Thebtaranonth Y, Wanauppathamkul S, Yuthavong Y. Antimalarial sesquiterpenes from tubers of Cyperus rotundus: Structure of 10,12-peroxycalamenene, a sesquiterpene endoperoxide. Phytochemistry. 1995;40:125–8. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(95)00260-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krishna S, Uhlemann AC, Haynes RK. Artemisinins: Mechanisms of action and potential for resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 2004;7:233–44. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ohira S, Hasegawa T, Hayashi KI, Hoshino T, Takaoka D, Nozaki H. Sesquiterpenoids from Cyperus rotundus. Phytochemistry. 1998;47:1577–81. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sonwa MM, König WA. Chemical study of the essential oil of Cyperus rotundus. Phytochemistry. 2001;58:799–810. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(01)00301-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tam CU, Yang FQ, Zhang QW, Guan J, Li SP. Optimization and comparison of three methods for extraction of volatile compounds from Cyperus rotundus evaluated by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2007;44:444–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim SJ, Kim HJ, Kim HJ, Jang YP, Oh MS, Jang DS. New patchoulane-type sesquiterpenes from the rhizomes of Cyperus rotundus. Bull Korean Chem Soc. 2012;33:3115–8. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yang JL, Shi YP. Structurally diverse terpenoids from the rhizomes of Cyperus rotundus L. Planta Med. 2012;78:59–64. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1280216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nagulendran KR, Velavan S, Mahesah R, Begum HV. In vitro antioxidant activity and total polyphenolic content of Cyperus rotundus rhizomes. E-J Chem. 2007;4:440–9. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Samariya K, Sarin R. Isolation and identification of flavonoids from Cyperus rotundus Linn. in vivo and in vitro. J Drug Deliv Ther. 2013;3:109–13. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou Z, Fu C. A new flavanone and other constituents from the rhizomes of Cyperus rotundus and their antioxidant activities. Chem Nat Compd. 2013;48:963–5. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhou Z, Yin W. Two novel phenolic compounds from the rhizomes of Cyperus rotundus L. Molecules. 2012;17:12636–41. doi: 10.3390/molecules171112636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ito T, Endo H, Shinohara H, Oyama M, Akao Y, Iinuma M. Occurrence of stilbene oligomers in Cyperus rhizomes. Fitoterapia. 2012;83:1420–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou Z, Zhang H. Phenolic and iridoid glycosides from the rhizomes of Cyperus rotundus Linn. Med Chem Res. 2013;22:4830–5. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhou Z, Yin W, Zhang H, Feng Z, Xia J. A new iridoid glycoside and potential MRB inhibitory activity of isolated compounds from the rhizomes of Cyperus rotundus L. Nat Prod Res. 2013;27:1732–6. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2012.750318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alam P, Ali P, Aeri V. Isolation of ketoalcohols and triterpenes from tubers of Cyperus rotundus Linn. J Nat Prod Plant Res. 2012;2:272–80. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kilani S, Bouhlel I, BenAmmar R, BenSghaiar M, Skandrani I, Boubaker J, et al. Chemical investigation of different extracts and essential oil from the tubers of (Tunisian) Cyperus rotundus. Correlation with their antiradical and antimutagenic properties. Ann Microbiol. 2007;57:657–64. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xu Y, Zhang HW, Yu CY, Lu Y, Chang Y, Zou ZM. Norcyperone, a novel skeleton norsesquiterpene from Cyperus rotundus L. Molecules. 2008;13:2474–81. doi: 10.3390/molecules13102474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Xu Y, Zhang HW, Wan XC, Zou ZM. Complete assignments of (1) H and (13) C NMR data for two new sesquiterpenes from Cyperus rotundus L. Magn Reson Chem. 2009;47:527–31. doi: 10.1002/mrc.2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Klahn P, Duschek A, Liébert C, Kirsch SF. Total synthesis of (+)-cyperolone. Org Lett. 2012;14:1250–3. doi: 10.1021/ol300058t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jeong SJ, Miyamoto T, Inagaki M, Kim YC, Higuchi R. Rotundines A-C, three novel sesquiterpene alkaloids from Cyperus rotundus. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:673–5. doi: 10.1021/np990588r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Komai K, Tang CS, Nishimoto RK. Chemotypes ofCyperus rotundus in Pacific Rim and Basin: Distribution and inhibitory activities of their essential oils. J Chem Ecol. 1991;17:1–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00994417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lawal OA, Oyedeji AO. Chemical composition of the essential oils of Cyperus rotundus L. from South Africa. Molecules. 2009;14:2909–17. doi: 10.3390/molecules14082909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ghannadi A, Rabbani M, Ghaemmaghami M, Malekian N. Phytochemical screening and essential oil analysis of one of the Persian sedges: Cyperus rotundus L. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2012;3:424–7. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jirovetz L, Wobus A, Buchbauer G, Shafi MP, Thampi PT. Comparative analysis of the essential oil and SPME-headspace aroma compounds of Cyperus rotundus L. Roots/tubers from South India using GC, GC-MS and olfactometry. J Essent Oil-Bearing Plants. 2004;7:100–6. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bisht A, Bisht GR, Singh M, Gupta R, Singh V. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of essential oil of tubers of C. rotundus Linn. Collected from Dehradun (Uttarakhand) Int J Res Pharm Biomed Sci. 2011;2:661–5. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Naves YR, Ardizio P. Volatile plant substances. CXXIX. The essential oil of Cyperus scarosius R. Br. Bull Chim Soc Fr. 1954:332–4. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dhingra SN, Dhingra DR. Essential oil of Cyperus scariosus. Perfumery Essent. Oil Rec. 1957;48:112–6. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nerali SB, Kalsi PS, Chakravarti KK, Bhattacharyya SC. Terpenoids LXXVII. Structure of isopatchoulenone, a new sesquiterpene ketone from the oil of Cyperus scariosus. Tetrahedron Lett. 1965;6:4053–6. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nigam IC. Essential oils and their constituents. XXXI. Cyperenone. A new sesquiterpene ketone from oil of Cyperus scariosus. J Pharma Sci. 1965;54:1823–5. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hikino H, Aota K, Takemoto T. Identification of ketones in Cyperus. Tetrahedron. 1967;23:2169–72. doi: 10.1016/0040-4020(67)80050-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Neville GA, Nigam IC, Holmes JL. Identification of ketones in cyperus. Tetrahedron. 1968;24:3891–7. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nerali SB, Chakravarti KK. Terpenoids CXVII-Structures of cyperenol and patchoulenol. Two new sesquiterpene alcohols from the oil of. Tetrahedron Lett. 1967;8:2447–9. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nerali SB, Chakravarti KK, Paknikar SK. Terpenoids. CXLIII. Rotundene and rotundenol, sesquiterpenes from Cyperus scariosus. Indian J Chem. 1970;8:854–5. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gopichand Y, Pednekar PR, Chakravarti KK. Isolation and characterization of (-)-β-selinene and isopatchoula-3,5-diene from Cyperus scariosus oil. Indian J Chem B. 1978;16B:148–9. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Uppal SK, Chhabra BR, Kalsi PS. A Biogenetically important hydrocarbon from C. scariosus. Phytochemistry. 1984;23:2367–9. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chowdhury JU, Yusuf M, Hossain MM. Aromatic plants of Bangladesh: Chemical constituents of rhizome oil of Cyperus scariosus R. Br. Indian Perfum. 2005;49:103–5. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pandey AK, Chowdhury AR. Essential oil of Cyperus scariosus R. Br. Tubers from Central India. Indian Perfum. 2002;46:325–8. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bhatt SK, Saxena VK, Singh KV. A leptosidin glycoside from leaves of Cyperus scariosus. Phytochemistry. 1981;20:2605. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bhatt SK, Sthapak JK, Singh KV. A new aurone from the leaves of Cyperus scariosus. Fitoterapia. 1984;55:171–6. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bhatt SK, Saxena VK, Singh KV. Stigmasta-5,24 (28)-diene-3b-O-a- L-rhamnopyranosyl-O-b-D-arabinopyranoside from leaves of Cyperus scariosus R. Br. Indian J Phys Nat Sci. 1982;2:15–7. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sahu S, Singh J, Kumar S. New terpenoid from the rhizomes of Cyperus Scariosus. Int J Chem Eng Appl. 2010;1:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Evans WC. 14th ed. London: WB Saunders Company Ltd; 1996. Trease and Evans’ Pharmacognosy; p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Greenish HG. 3rd ed. Jodhpur: Scientific Publishers (India); 1999. Materia Medica; pp. 323–9. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gupta M, Shukla Y, Lal R. Oxo fatty acid esters from Cryptocoryne spiralis rhizomes. Phytochemistry. 1983;22:1969–71. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gupta MM, Lal RN, Shukla YN. Oxo fatty acids from Cryptocoryne spiralis rhizomes. Phytochemistry. 1984;23:1639–41. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gupta MM, Shukla YN. 5α-Stigmast-11-en-3 β-yl palmitate and 24-ethyl-5α-cholesta-8 (14),25-dien-3 β-yl stearate, two steryl esters from Cryptocoryne spiralis rhizomes. Phytochemistry. 1986;25:1423–5. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sivapalan SR. Medicinal uses and pharmacological activities of Cyperus rotundus Linn.– A review. Int J Sci Res Publ. 2013;3:1–8. [Google Scholar]