Abstract

Objectives:

This study was performed to know the prevalence of primary headache disorders in school going children of central India and to elucidate the effects of various sociodemographic variables like personality or behavior traits, hobbies like TV watching, school life or study pressure in form of school tests, family history of headache, age, sex, body habitus etc., on prevalence of primary headaches in school going children of central India.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional school-based study was performed on 500 school children (aged 7–14 years) for the duration of 1 year. Potential triggering and aggravating demographic and social variables were investigated based on a diagnosis of International Classification of Headache Disorder-II headache.

Results:

The prevalence of recurrent headache was found to be 25.5% in Indore. Of the studied population, 15.5% had migraine, 5% had tension-type headache migraine, and 5% had mixed-type headache symptoms suggesting both of above. Overall headaches were found to be more common among girls, but tension-type was more common in boys. Using regression analysis, we found that sensitive personality traits (especially vulnerable children), increasing age, female gender and family history of headache had a statistically significant effect on headaches in children. In addition, mathematic or science test dates and post weekend days in school were found to increase the occurrence of headache in school-going children. Hobbies were found to have a significant effects on headaches.

Conclusion:

As a common healthcare problem, headache is prevalent among school children. Various sociodemographic factors are known to trigger or aggravate primary headache disorders of school children. Lifestyle-coping strategies are essential for school children.

Keywords: Migraine, schoolchildren, tension-type headache

Introduction

Headache is one of the most frequent complaints evaluated by internists and neurologists in the office practice.[1] Headache is also a common complaint observed in childhood.[2] Primary headaches are unaccompanied by any structural, metabolic or any other lesion in the body in general and brain, in particular, whereas secondary headaches are caused by exogenous disorders.[3] Many epidemiological studies on headache disorders show that migraine and tension-type headache (TTH) are more common in childhood.[4,5] However, the prevalence of migraine and TTH was found to be in different ranges. The prevalence of migraine in Asian countries was reported in the range of 1–22%, lower than in North American and European countries.[6,7,8] In previous studies, the prevalence of migraine was found in the range of 3.7–34.4%, and the prevalence of TTH in the general population was also reported to vary significantly (0.7 - 18%).[9] There is growing evidence available that the differences in reported TTH and migraine prevalence rates may be related to their comorbid association, which remains poorly defined. Epidemiological studies discuss the differences in prevalence rates of headache by geographical and socioeconomic variables.[9,10] The presentation of headaches may also depend on many factors including genetic factors as well as the children's school, home, and social life.

Migraine is a ubiquitous familial disorder characterized by periodic, often unilateral, pulsatile headache, which begins in childhood, adolescence or early adult life and recurs with diminishing frequency during advancing years. Migraine with aura (classic or neurologic migraine) is ushered in by an evident disturbance of nervous function, most often visual, followed in a few minutes by hemicranial or in about 1/3rd of the cases, by bilateral headache, nausea, and sometimes vomiting, all of which last for 4–72 h. Migraine without aura (common migraine) is characterized by a sudden onset of hemicranial or less often by global headache with or without nausea and vomiting, which then follows the same temporal pattern as the migraine with aura. Photophobia and phonophobia accompany both types of migraine.[3] Migraine and TTH have been considered distinct entities by the International Headache Society.[11]

Headaches in children lead to a poorer quality-of-life and decreased success in school. Focusing on personality traits and lifestyle is more important to recognize and prevent the headaches. In addition, many studies suggest that stress is related with headaches in adolescents.[12,13] The potential risk factors, including school courses and tests, may be responsible for headaches. A poor psychosocial life may also have a role on headaches. No studies are available in the literature showing the effects of the hobbies, personality traits, school life, and the presence of siblings on headaches in school children. Hence, it is essential to find the key points in the etiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment in childhood.

This study aimed to determine the prevalence of migraine and TTH in adolescents and also investigates the effects of sex, age, school tests, hobbies, personality traits, and family history of headache in 7–14 years old school going children in central India.

Materials and Methods

Eligible subjects included 500 students between 7 and 14 years of age from various schools of Indore city for a period of 1-year. Verbal permissions were taken from the school children and their parents before applying the survey, and the aim of the study was explained to them. The study was a questionnaire survey on factors affecting headache and the prevalence of headaches in Indore city. The sample size calculated by the Epi Info 7 version using microsoft windows XP, with 95% confidence interval, prevalence (P) = 0.50 (unknown prevalence) and 0.05 precision (d). The present study was designed as a school-based, cross-sectional, and selective (2nd–7th grades) study. Students were classified into groups of 15–20 in each class and a detailed explanation of each question was given by a study neurologist (MY) and student's guidance counselor in each class before answers were sought for the questions. A self-administered 10-item questionnaire was answered by all the students and their parents. The questionnaire included headache, personality traits, family history, and hobbies-related questions. The children's personality traits were identified based on subjective observations made by the families. Then children with headache answered 10 questions about the symptoms of pain and its severity. The classification of headache was based on International Classification of Headache Disorder (ICHD-II). The data were processed and analyzed using SPSS-18 manufactured by IBM - India for Windows Fisher's exact test, Pearson correlations, and Pearson's Chi-square test; and logistic regression was used for the comparison of categorical and scale variables. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Among the groups, variables which were found to be statistically significant and variables that are not conceptually compatible were added to the logistic regression model. Encounter with headache (yes, no) has been grouped and added to the logistic regression model as a dependent variable.

Results

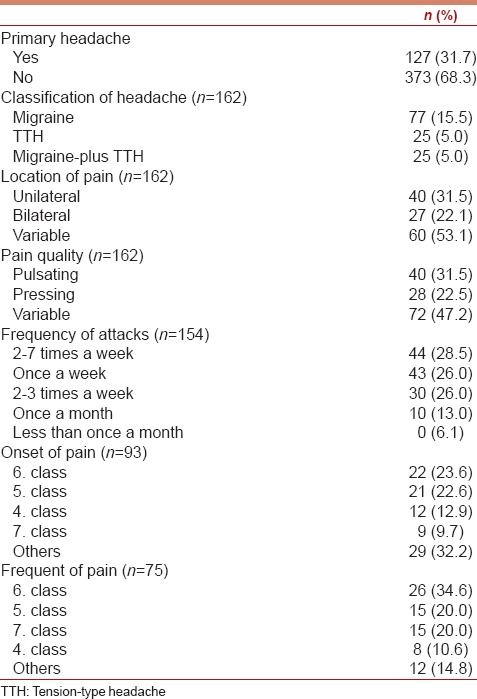

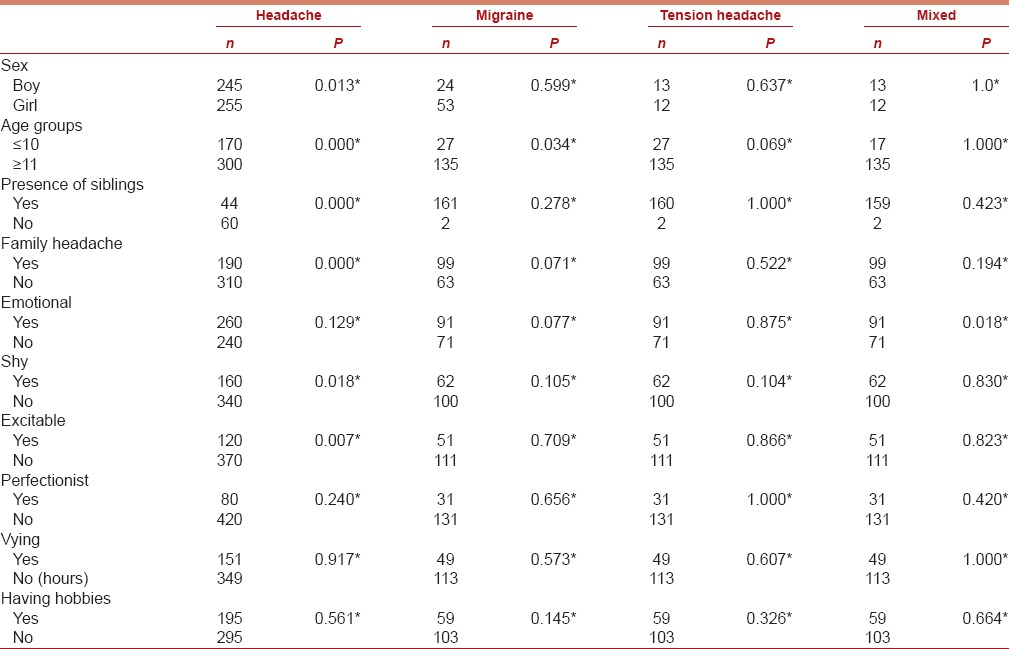

A total of 500 students participated in this study: 255 girls and 245 boys were included and aged 7–14 years. Recurrent headache was found in 127 participants. 77 girls and 50 boys had headache. The distribution of children with primary headaches based on the ICHD-II criteria was as follows: 77 children (15.5%) had migraine 25 children (5%) were diagnosed with TTH, 25 children (5%) were diagnosed with mixed migraine plus TTH. Headache was significantly more common in girls than in boys (P < 0.05). The prevalence of headache increased gradually with age in both sexes (P < 0.05). According to the questionnaire, 31.5% of the students had unilateral headache of pulsating quality and associated nausea and/or vomiting in 21.6%.

In this study, of the 77 total children with migraine, 16 children (20.7%) were diagnosed as having migraine with aura. The prevalence of migraine with aura was found to be 3.2%. 78 children (62%) had a school day loss and failed to do homework. There was a family history of headache in 38.1%. Headache prevalence increased more than 4 times in children with family history of headache. 39.9% of headaches were activated by noise, 48.9% by noise, 33.4% by hunger, 52.3% by fatigue, and 52.7% by distress. Headache was relieved through rest in 80%.

Students with three or more headaches a month were followed for 3 months and the most common day for headaches was found to be Monday with 28.5% (r: 0.128, P: 0.022). The rate of headaches in weekends was found to be 5.9%. In 56.5% of the students, headache was detected on the day of tests and 18.3% of these tests were science, 19.4% were mathematic tests. Headache prevalence was found to be 15% in students with hobbies and 42% in students without hobbies (P > 0.05). Based on their families’ subjective observations, the children's personality traits were as follows: 62.4% emotional, 38.5% shy, 17.7% excitable, 13.7% perfectionist, and 19.7% vying. Headache was more common for emotional, shy, and excitable subjects (P = 0.016, 0.015, and 0.005 respectively).

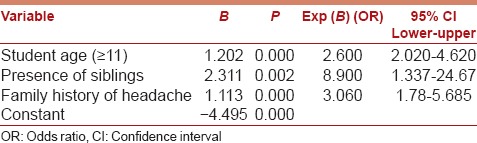

According to logistic regression analysis, 12 years and over age, presence of siblings, family history of headache and sleep disturbances significantly increases the frequency of headache of students (odds ratio [OR] = 2.6, CI: 2.02–4.62, OR = 8.9, CI: 1.33–24.67, OR = 3.06, 1.78–5.68, OR = 3.54, 2.05–5.92, respectively). Results are shown in Tables 1-3.

Table 1.

Headache feature of school students

Table 3.

According to logistic regression results, the features that affect to frequency of meeting with headache of the students

Table 2.

The association of several characteristics with headache presence

Discussion

Headache in the pediatric population is underdiagnosed and undertreated, despite a high prevalence of headache disorders in children and adolescents. Headaches, although not uncommon during childhood, tend to increase in frequency during adolescence. This study intended to show the prevalence of headache disorders among school children in Indore. We also investigated the incidence and types of headaches on specific affecting factors including personal characteristics, hobbies, tests, and sex. There are no studies available in the literature showing the effects of sociodemographic factors on the prevalence of childhood headache including school tests, hobbies and personality traits of school children.

We found a headache prevalence of 25.5% in school children aged 7–14 years old in Indore. There are reports in the literature suggesting varying headache prevalence in children with different ages. Our result about the prevalence of headache is higher than in studies made in China (9,68%, aged 9–15), Sweden (24.4% aged 7–15), Finland (5.7%, aged 7).[14,15,16] Another study in Turkey suggested that the prevalence of headache was 46.2% in children aged 6–10.[16,17,18] Epidemiological studies also have different prevalence in Asian, North American, and European countries.[6,7,19] It is certain that the headache prevalence varies in different countries. Our study confirms that headache is a common problem in school children population in Indore. We also found the prevalence to be higher in girls. Mortimer et al. found that migraine prevalence was higher in boys than girls under 7 years, and that prevalence was equal at 7–11 years.[20] Bugdayci et al. suggested that the prevalence of headache was higher in girls than boys with increasing age.[21]

Headache, especially migraine, is an outcome of the interaction between organic, psychological, and psychosocial factors. The differences in sex in the development of migraine and TTH may be related to hormonal influences. It is notable that puberty changes hormonal levels, and personal features may also be different. Furthermore, the personality trait is more labile in girls so that the personal sensitivity may reflect the influence on headache. This study determines that vulnerable children have higher prevalence of headache. We found that the prevalence of headaches in school children increases with increasing age. It is notable that the prevalence of headache was influenced by variables in sex, age and personality traits.

Heredity and family background was found to be of great importance in many previous studies.[22,23] A positive family history is more common among patients with headache.[23] A family history (especially maternal) of headaches is more common among school children with migraine (P < 0.001). The genetic contribution to migraine was showed in several studies and indicated that this family history of headache was more common on the maternal side.[10,17,24]

Children with migraine seem to have more emotional symptoms than children without migraine.[25] Some points should also be clarified to understand the effects of social and environmental factors for headache. There are limited number of studies investigating the relationship between hobbies and headache. The prevalence of headache was found to be less in people having a regular hobby without the stress.[21] The same finding was found in our study.

This study found that tests were significantly associated with headache. Especially, the math-test dates cause headaches. Mathematics and science courses are considered to be difficult, so it causes stress, resulting in headache.

It was reported that emotional problems were related with headaches.[26,27,28] Different from previous field studies, follow-up of children over a period of 3 months, and investigation into the relationship of headache with tests as well as effects of the development and pursuit of hobbies on headache in children are the strengths of this study.

Conclusion

This study identified the coping strategies with migraine and TTH cases, also concluding that stress factors including school courses and personality traits also need to be considered.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Raieli V, Raimondo D, Cammalleri R, Camarda R. Migraine headaches in adolescents: A student population-based study in Monreale. Cephalalgia. 1995;15:5–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1995.1501005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perquin CW, Hazebroek-Kampschreur AA, Hunfeld JA, Bohnen AM, van Suijlekom-Smit LW, Passchier J, et al. Pain in children and adolescents: A common experience. Pain. 2000;87:51–8. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00269-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goadsby PJ, Raskin NH. Headache. In: Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, et al., editors. Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. United States of America: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc; 2008. pp. 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monteith TS, Sprenger T. Tension type headache in adolescence and childhood: Where are we now? Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2010;14:424–30. doi: 10.1007/s11916-010-0149-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zencir M, Ergin H, Sahiner T, Kiliç I, Alkis E, Ozdel L, et al. Epidemiology and symptomatology of migraine among school children: Denizli urban area in Turkey. Headache. 2004;44:780–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stovner Lj, Hagen K, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Lipton R, Scher A, et al. The global burden of headache: A documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:193–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, Diamond ML, Reed M. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: Data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache. 2001;41:646–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2001.041007646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis DW. Headaches in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65:625–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim BK, Chu MK, Lee TG, Kim JM, Chung CS, Lee KS. Prevalence and impact of migraine and tension-type headache in Korea. J Clin Neurol. 2012;8:204–11. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2012.8.3.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alp R, Alp SI, Palanci Y, Sur H, Boru UT, Ozge A, et al. Use of the International Classification of Headache Disorders, Second Edition, criteria in the diagnosis of primary headache in schoolchildren: Epidemiology study from eastern Turkey. Cephalalgia. 2010;30:868–77. doi: 10.1177/0333102409355837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders. Cephalalgia. (2nd ed) 2004;24(Suppl 1):9–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2003.00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houle TT, Butschek RA, Turner DP, Smitherman TA, Rains JC, Penzien DB. Stress and sleep duration predict headache severity in chronic headache sufferers. Pain. 2012;153:2432–40. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maleki N, Becerra L, Borsook D. Migraine: Maladaptive brain responses to stress. Headache. 2012;52(Suppl 2):102–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2012.02241.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jin Z, Shi L, Wang YJ, Yang LG, Shi YH, Shen LW, et al. Prevalence of headache among children and adolescents in Shanghai, China. J Clin Neurosci. 2013;20:117–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2012.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laurell K, Larsson B, Eeg-Olofsson O. Prevalence of headache in Swedish schoolchildren, with a focus on tension-type headache. Cephalalgia. 2004;24:380–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2004.00681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Isik U, Topuzoglu A, Ay P, Ersu RH, Arman AR, Onsüz MF, et al. The prevalence of headache and its association with socioeconomic status among schoolchildren in istanbul, Turkey. Headache. 2009;49:697–703. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aromaa M, Sillanpää M, Rautava P, Helenius H. Pain experience of children with headache and their families: A controlled study. Pediatrics. 2000;106:270–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.2.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karli N, Akgöz S, Zarifoglu M, Akis N, Erer S. Clinical characteristics of tension-type headache and migraine in adolescents: A student-based study. Headache. 2006;46:399–412. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Akyol A, Kiylioglu N, Aydin I, Erturk A, Kaya E, Telli E, et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of migraine among school children in the Menderes region. Cephalalgia. 2007;27:781–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mortimer MJ, Kay J, Jaron A. Epidemiology of headache and childhood migraine in an urban general practice using Ad Hoc, Vahlquist and IHS criteria. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1992;34:1095–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1992.tb11423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bugdayci R, Ozge A, Sasmaz T, Kurt AO, Kaleagasi H, Karakelle A, et al. Prevalence and factors affecting headache in Turkish schoolchildren. Pediatr Int. 2005;47:316–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.2005.02051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rasmussen BK. Migraine and tension-type headache in a general population: Psychosocial factors. Int J Epidemiol. 1992;21:1138–43. doi: 10.1093/ije/21.6.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gervil M, Ulrich V, Kaprio J, Olesen J, Russell MB. The relative role of genetic and environmental factors in migraine without aura. Neurology. 1999;53:995–9. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.5.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arruda MA, Bigal ME. Migraine and behavior in children: Influence of maternal headache frequency. J Headache Pain. 2012;13:395–400. doi: 10.1007/s10194-012-0441-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bigal ME, Lipton RB. What predicts the change from episodic to chronic migraine? Curr Opin Neurol. 2009;22:269–76. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e32832b2387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luntamo T, Sourander A, Rihko M, Aromaa M, Helenius H, Koskelainen M, et al. Psychosocial determinants of headache, abdominal pain, and sleep problems in a community sample of Finnish adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;21:301–13. doi: 10.1007/s00787-012-0261-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palma JA, Urrestarazu E, Iriarte J. Sleep loss as risk factor for neurologic disorders: A review. Sleep Med. 2013;14:229–36. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raggi A, Giovannetti AM, Quintas R, D’Amico D, Cieza A, Sabariego C, et al. A systematic review of the psychosocial difficulties relevant to patients with migraine. J Headache Pain. 2012;13:595–606. doi: 10.1007/s10194-012-0482-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]