Abstract

Rare type of calvarial defects seen in patients with neurofibromatosis type-1 (NF1) is presented. The issues of pathogenesis and management are discussed. Two cases of NF1 with skull defects in the region of the lambdoid suture are reported. The possible etiological basis and nature of these type of defects and management issues are discussed. The calvarial skull defects in the lambdoid suture region are rare defects in NF1 patients. The possible reason of the progressive nature of these type of lesions can be the cerebrospinal fluid pulsations behaving like “growing skull fractures,” especially when not associated with structural lesions. It leads to progressive enlargement of the small congenital defects in the region of the lambdoid suture and abnormal susceptibility of bones for resorption. For these defects, conservative management is suggested due to its progressive nature and high chances of operative treatment failure.

Keywords: Calvarial defects, dural ectasia, growing skull fractures, lambdoid suture, neurofibromatosis type-1

Introduction

Neurofibromatosis type-1 (NF1) also known as Von Recklinghausen disease is one of the most common neurocutaneous disorders with multisystem involvement. NF1 is a disorder affecting approximately one in 3000 persons worldwide.[1] Osseous manifestations have been reported in approximately 50% of patients with NF1.[2] A number of bone defects have been described in NF1 patients - out of those skull bone defects are of rare occurrence. The commoner anomalies are scoliosis (10–26% of patients), absence of the greater sphenoid wing (3–11.3%), tibial pseudoarthrosis (1–4%), short stature, spinal meningocele, and macrocephaly.[3] Among a number of skull bone defects described sphenoid wing dysplasia and orbital defects are some of the common ones while calvarial defects are very rare entities.

So far, calvarial bone defect in the region of the lambdoid suture have been described in very few publications and majority of them are associated with overlying plexiform neurofibromas and/or dural ectasia requiring surgical intervention. Many times these calvarial skull defects have been attributed to overlying plexiform neurofibroma leading to progressive bone resorption. Here, we are presenting two cases of NF1 with lambdoid suture bone defect without associated plexiform neurofibroma or dural ectasia. One of those patients had a history of mild bulge at occipital region, which was asymptomatic and in the other patient it was detected incidentally while being investigated for altered sensorium following fall from height.

Case Reports

Case 1

First patient is 16-year-old boy who presented with drooping of right upper eyelid and prominence of right eyeball since 3 years. He also noticed multiple hyperpigmented patches on the trunk over last 4 years.

On examination, patient had multiple cafe au lait spots over the back and trunk. He also had occipital scalp swelling since birth which was nonprogressive. Right eye was lower than left. Hollowness was noted in right frontotemporal region above right eyebrow. Skull defect of size 8 × 6 cm over the lambdoid region, centering on midline was noted.

Computerized tomography scan head showed parieto-occipital bone defect in midline in the region of the lambdoid suture with cystic encephalomalacia right parieto-occipital lobe and porencephalic change [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Computerized tomography showing midline parieto-occipital bone defect with right parieto-occipital encephalomalacia and right orbital roof defect

The roof of the right orbit was absent. There was the herniation of meninges and brain into the right orbit through orbital roof bone defect with increased right orbital transverse diameter [Figure 1].

This patient underwent ophthalmological evaluation for visual acuity and fields, which were within normal limits. He was advised to be under follow-up to look for deterioration of visual acuity or worsening of the proptosis.

Case 2

This 13-year-old boy presented with a history of the fall from stairs. There was no eye witness account of the events leading to or following the fall. The patient was found in altered sensorium. On evaluating history, patient was born of consanguineous parentage. He had congenital cleft lip and palate for which he was operated 2 years earlier. His first degree cousin had bilateral lower limb bone abnormality with abnormal curvature.

On examination, patient was in altered sensorium with Glassgow coma scale of E2M5V2. He had multiple café au lait spots all over body with axillary freckling.

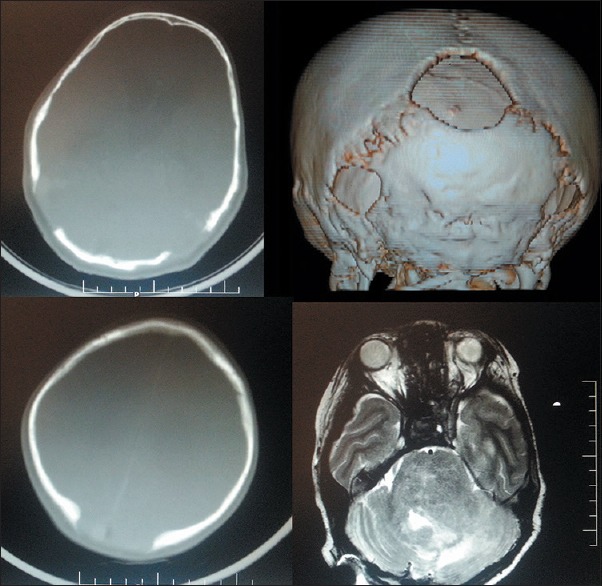

Computerized tomography head showed midline parieto-occipital as well as bilateral lateral skull defect in the region of the lambdoid suture without evidence of dural ectasia or brain bulge [Figure 2]. He did not have other associated bone defects. It also showed diffuse brain stem glioma with hydrocephalus so initially right frontal external ventricular drain was placed, and patient improved in sensorium. Hence, medium pressure ventriculo-peritoneal shunt was done. Following which magnetic resonance imaging brain plain and with contrast was done, and he was referred to an oncologist for radiation therapy for diffuse brain stem glioma.

Figure 2.

Computerized tomography with three-dimension reconstruction showing midline as well as bilateral lateral lambdoid suture defects and magnetic resonance T2-weight image (right lower image) showing diffuse pontine glioma

Discussion

In both of these cases, patients had lambdoid suture bone defect without dural ectasia or associated plexiform neurofibroma overlying the defect. The patient discussed in case 1 had proptosis due to isolated orbital roof defect without sphenoid wing defect. As the proptosis was nonprogressive, and vision was unaffected, he was put on follow-up. The patient discussed in case 2 had diffuse brain stem glioma with hydrocephalus, which was managed with shunt and standard adjuvant chemoradiation. The skull defect per se did not require treatment. He was also put on regular follow-up.

The pathological reason for the development of these types of skull defects is still unclear. Progressive bone resorption is seen in bone defects in the convexity as opposed to skull base defects. The sphenoid wing and the orbital roof defects are nonprogressive and congenital in origin. The calvarial bone defects may be attributed to bone resorption due to overlying plexiform neurofibroma or meningioma when present.

We hypothesize that the calvarial defects may be of congenital origin due to primary mesenchymal hypoplasia or dysplasia especially when the defect is involving the skull base as in sphenoid wing and orbital roof defects. They may also be of acquired origin due to secondary enlargement of small fusion defects occurring in skull convexity in the region of sutures. The overall picture may be like “growing skull fractures” due to the effect of cerebrospinal fluid pulsations transmitted to the defect [Figure 3]. This leads to progressive osteolysis in the region of sutures as in both our cases. Susceptibility of bones to resorption due to pressure effect and/or change in mineral microenvironment is another possibility.

Figure 3.

Graphical presentation of small defect in lambdoid suture with cerebrospinal fluid pulsations causing enlargement

As far as the management of these type of skull defects In NF1 cases is concerned, there are no guidelines. Attempted cranioplasties have failed due to the progressive nature of these defects.[4] Hence, the suggested management would be the “wait and watch” policy, especially when the patients are asymptomatic. So far, both of our patients are under 3 years and 6 months follow-up respectively and doing fine.

Conclusion

The calvarial bone defects can be seen as the part of NF1 symptom complex. Majority of them are benign and do not require any repair.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Cohen MM Jr, Neri G, Weksberg R, editors. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002. Neurofibromatosis, in Overgrowth Syndromes; pp. 130–45. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crawford AH, Jr, Bagamery N. Osseous manifestations of neurofibromatosis in childhood. J Pediatr Orthop. 1986;6:72–88. doi: 10.1097/01241398-198601000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedman JM. Epidemiology of neurofibromatosis type 1. Am J Med Genet. 1999;89:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mislow JM, Proctor MR, McNeely PD, Greene AK, Rogers GF. Calvarial defects associated with neurofibromatosis type 1. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 2007;106(6 Suppl):484–9. doi: 10.3171/ped.2007.106.6.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]