Abstract

Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) syndrome is a rare mitochondrial disease. The available studies on MELAS syndrome are limited to evaluation of radiological, audiological, genetic, and neurological findings. Among the various neurological manifestations, speech-language and swallowing manifestations are less discussed in the literature. This report describes the speech-language and swallowing function in an 11-year-old girl with MELAS syndrome. The intervention over a period of 6 months is discussed.

Keywords: 3243A >G mutation, mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes syndrome, mitochondrial DNA, rehabilitation, speech-language, swallowing

Introduction

The mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) syndrome, first described in 1984 by Pavlakis et al. is a multisystem disorder characterized by clinical stroke, seizures, lactic acidosis, ragged red fibers, exercise intolerance, and onset of symptoms before the age of 40.[1] Other manifestations comprise dementia, limb weakness, short stature, hearing loss and recurrent migraine-like headaches.[2,3,4] The audiological manifestations in mitochondrial disorders are well-characterized.[5,6] Voice and swallowing problems are also reported in different phenotypes of mitochondrial disease in adults. Most of the available literature focuses on the audiological findings of children with sparse details on the speech-language and swallowing profile.[5,6,7] The different speech subsystems involving respiratory, laryngeal, resonatory, articulatory, and prosodic subsystems may be differentially involved depending on the extent of muscular and neurological involvement. The present case report aims to highlight the speech-language and swallowing issues and intervention in an 11-year-old girl with MELAS syndrome over a 6-month follow-up.

Case Report

An 11-year-old girl second born to Indo - Japanese parentage presented with a history of recurrent stroke-like episodes since the age of five. She was confirmed to have m.A3243A > G mutation in the mitochondrial (mt) tRNALeu at the age of 5 years, on presentation to our center. On examination, she was short-statured and had striking hypertrichosis. She was alert and could respond to queries by smiling. There was hypotonia of all four limbs with brisk deep tendon reflexes and extensor plantar response. Her academic performance was good till first standard after which she gradually regressed in terms of speech, hearing, cognitive-linguistic, and motor skills along with difficulties in swallowing. There was a gradual decline in IQ from 79 to 54 over a period of 4 years. Evaluation showed lactic acidosis. Her magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at the age of 12 years showed bilateral symmetrical signal changes in the basal ganglia, white matter, and cerebral cortex with moderate atrophy. She received mitochondrial cocktail medications, arginine hydrochloride along with multiple antiepileptic medications.

Family history was significant with mother having history of stroke-like episodes, two episodes of status epilepticus, and history of thyroid carcinoma operated at 32 years of age. Matrilineal grandmother reportedly had auditory problem, diabetes mellitus, brain infarction, and died of cancer with unknown primary lesion. Both mother and grandmother had the m. 3243A >G mutation as per the reports.

Audiological findings

At 7 years of age, her initial audiogram revealed right moderate conductive hearing loss and C type right tympanometry. Follow-up audiogram at 11 years of age revealed mild and minimal sensorineural hearing loss in the right and left ear, respectively. Otoacoustic emissions (OAEs) were also absent bilaterally indicating cochlear dysfunction.

Speech-language and dysphagia evaluation

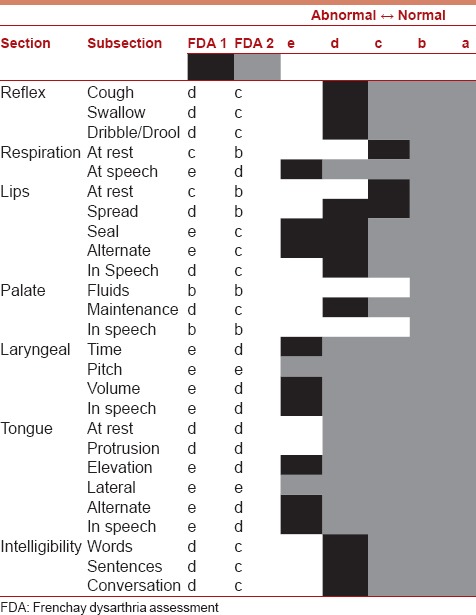

Analysis of language milestones revealed that she started babbling at the age of 6 months and had age adequate language use and mean length of utterance till 6 years of age. There was a gradual deterioration in speech-language and swallowing since 7 years of age with use of bisyllabic words and gestures for communication, articulatory difficulties, and soft voice. She often answered a direct question with a single word (mostly bisyllabic) or did not answer at all and needs constant prompting to respond. Tongue showed choreiform movements with dystonia and pooling of saliva. Speech and language evaluation at 11 years of age using receptive-expressive emergent language scales (REELS) revealed the child's receptive language as 24 months and expressive language as 12–14 months.[8] The child's communicative intent was poor and needed frequent prompts to communicate. The Frenchay Dysarthria Assessment (FDA) was administered to assess the speech and nonspeech oro-motor abilities of the child.[9] The profile of the FDA results during first visit and after six sessions of speech-language and dysphagia intervention spanning 5 months is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

FDA done at 11 years of age (May 2012 (FDA-1) and October 2012 (FDA-2))pre-and post-six sessions of speech-language intervention shows significant improvement in all speech subsystems. (FDA1-Black; FDA2-Grey)

It is evident from Table 1 that the child showed significant deficits in most of the subsections, particularly respiratory support for speech, lip seal, laryngeal, and tongue subsections during the first evaluation (FDA-1) which improved after intervention spanning 5 months (FDA-2). Patient had difficulty in swallowing, reduced food intake, weight loss, and drooling of saliva. Pharyngeal weakness was prominent in the form of drooling and difficulty in taking liquids. Parents reported progressive loss of ability to chew, make vertical and lateral jaw movements, and difficulty in swallowing. Child could take all consistencies of food till 7 years of age after which child was mainly on the liquid diet or homogenous pureed forms, porridge and biscuit (dry, can bite and soak in saliva). Feeding time was prolonged, and there was prominent pocketing of food on the anterior part of the hard palate and on both sides of the buccal cavity. Child was able to clean the tongue relatively well, but there was dribbling of consumed food. Typical intake consisted of half glass of milk with beaten egg.

On evaluation, child had difficulty with voluntary opening and closing of the mouth, chewing certain food textures, tastes, etc. Child was unable to drink from a cup or bottle and had to be spoon fed. Sucking and rotary chewing were absent. Parents reported presence of choking when the quantity of food was approximately more than 2.5 ml. Child was often fed by the parents, positioned in a chair. It took the child an average of 45 min for drinking 70 ml of milk. Poor lip seal, pooling of saliva, and frequent drooling were also observed. Parents reported significant weight loss since 10 years of age.

Intervention

Based on the speech-language and dysphagia evaluation, intervention incorporating exercises to improve swallowing functions which included exercises to improve jaw closure, to increase the tone in the posterior sections of the tongue, and to restore rotary chewing as described in Gallender was undertaken.[10] Alternative and augmentative communication and improving receptive and expressive vocabulary were the second goal. Oro-motor exercises and phonetic stimulation were also recommended.

Discussion

This report presents the speech-language and swallowing evaluation in an 11-year-old child with MELAS syndrome diagnosed based on the clinical findings of recurrent stroke like episodes, lactic acidosis, MRI findings, and the m. 3243A > G mutation in the mtDNA. She had mild sensory neural hearing loss on audiological evaluation. Speech and language evaluation showed significant deficits and regression of speech-language, hearing and swallowing abilities over a period of 4 years. Rehabilitation of these functions resulted in improvement over 6 months. This is evident from the improvement in FDA scores before (FDA-1) and after (FDA-2) intervention. The FDA total score prior to intervention was 9.28 whereas score after intervention was 16.71. Improvement in language was judged using REELS.[8]

The findings of the present study are in accordance with literature findings reporting cognitive deficits, global impairment, and sensorineural hearing impairment accompanying mitochondrial dysfunction.[2,3,4] Oro-motor abilities were significantly affected in terms of reduced reflexes and difficulty obtaining lip seal and reduced tongue and laryngeal movements. Breath support for speech was also reduced. These findings are expected due to the multisystem presentation of MELAS including neurological and muscular symptoms, which can affect different speech subsystems differentially.

Hearing loss is a frequently associated feature of mitochondrial disease.[5,6] Audiological evaluation at 7 years of age revealed a right sided moderate conductive hearing loss with “C” type tympanogram suggesting eustachian tube malfunction. Child had good speech discrimination scores (>90% in both ears). Cochlear dysfunction was ruled out with OAEs, which were bilaterally present in both ears for more than three frequencies. A mild and minimal sensorineural hearing loss was identified in the follow-up evaluation at 11 years of age. Cochlear dysfunction was also substantiated by the bilateral absence of otoacoustic emissions. Mild to severe sensorineural hearing loss of cochlear origin is seen in more than 75% of patients with MELAS syndrome.[11] The outer hair cells of the cochlea are highly metabolically active and are highly sensitive to reduce intracellular adenosine triphosphate production and mitochondrial dysfunction. This is the reason for the frequent association of sensorineural hearing loss with mitochondrial dysfunction. Brainstem auditory evoked potentials during both evaluations suggested bilateral presence of all waves at near normal latencies and hence the absence of retrocochlear involvement. Parents were counseled on the need for regular hearing evaluation for the child at an interval of 6 months. The hearing loss associated with mitochondrial disease may be mild or subclinical and if not evaluated specifically may be missed in the clinical diagnosis.

Speech and language evaluation findings revealed regression in speech and language skills over a period of 4 years spanning from seven to 11 years of age. She had near normal cognitive-linguistic skills till 7 years of age after which there were regressions and occasional remissions of language skills. At 11 years of age, the girl was using only two or three single words (only if prompted continuously) for communication. There are reports of cognitive decline and dementia as being associated with MELAS.[2,3,4] Studies have also mentioned the presence of aphasia, particularly episodic aphasia associated with repeated “stroke-like” episodes which also recovers quickly. They have also stated instances of steadily declining communication at the semantic-pragmatic level.[7] Language disturbances in MELAS are rarely addressed in the growing research evidence on mitochondrial cytopathies. There are only passing references of the fact that aphasia may occur among many other neurological disturbances in the later stages of MELAS.[7] Increasingly, sparse and slow discourse production is also reported as a characteristic feature of MELAS. Language disturbance in MELAS is also characterized by drastic worsening of language followed by quick remission, with some residual deficits after each stroke-like episode. Significant anomia is also reported to recede within hours after onset.[7] The pattern of language in this case concurs with these literature findings. The language impairment in our patient is multifactorial and includes frequent regressions followed by quick recovery. However, it is noticeable that the recovery of language is not age adequate. The recovered receptive language is more often around 2 and 3 years level whereas expressive language is often <18 months of age. The profile of language impairments also seems to indicate a gradual decline in cognitive-linguistic abilities in this child following several episodes of regression. This is also evidence for the reduction in IQ and poor academic performance over a period of time spanning 4 years.

Dysphagia is often associated in MELAS due to generalized muscle weakness.[12] Weakness of the lips, tongue or jaw impairs the bolus preparation and increases swallow time. Palatal weakness may lead to nasal regurgitation. All of this together may lead to impaired bolus transit, pharyngeal pooling and risk of aspiration. Respiratory muscle weakness may impair the cough reflex and may lead to other complications.[12] The girl exhibited significant oropharyngeal neurogenic dysphagia with increased oral transit time, anterior spillage, and occasional palatal stick. Pharyngeal swallow reflex was also prolonged, and feeding time was prolonged with inadequate nutritional intake.

The findings demonstrate the need for routine evaluation of speech-language and swallowing in children with mitochondrial disease and need for early intervention. The intervention focused mainly on oro-motor exercises, phonetic placement, and articulation drill as well as dysphagia intervention. Dysphagia intervention included a series of exercises to enhance jaw closure, tongue, and lip strength. It also included dietary manipulation in terms of changing consistency of food and liquids and use of safe swallow strategies. Oro-motor control exercises and phonetic stimulation were also taken up. The child showed improvement in the areas of speech-language comprehension and expression, oro-motor abilities, and swallowing movements over 6-month follow-up.

As a case report, the findings cannot be generalized. The language symptoms associated with mitochondrial disease are quite variable and may show recovery immediately. It may be predominantly neurological symptoms in the beginning, and hence these go unnoticed. Hence, a detailed clinical evaluation or intervention is rarely done at least in the early stages. Symptomatic treatment focusing on the different aspects of speech-language and to facilitate smooth swallow is essential in children with MELAS syndrome. It involves a multidisciplinary team of neurologists, pediatricians, speech-language pathologists, audiologists, and occupational therapists. The goals have to be modified according to the evolving symptoms and needs of the child and the family. These may help in palliation of some of the symptoms, supportive care and slow the course of the illness. Early intervention of speech-language, dysphagia, and hearing problems is essential to prevent social isolation, malnutrition and to improve the quality-of-life. The evolution of speech-language and swallowing issues and the long-term effects of the intervention on these need to be explored further in this cohort of patients.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Pavlakis SG, Phillips PC, DiMauro S, De Vivo DC, Rowland LP. Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes: A distinctive clinical syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1984;16:481–8. doi: 10.1002/ana.410160409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirano M, Ricci E, Koenigsberger MR, Defendini R, Pavlakis SG, DeVivo DC, et al. MELAS: An original case and clinical criteria for diagnosis. Neuromuscul Disord. 1992;2:125–35. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(92)90045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirano M, Pavlakis SG. Mitochondrial myopathy, encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes (MELAS): Current concepts. J Child Neurol. 1994;9:4–13. doi: 10.1177/088307389400900102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ciafaloni E, Ricci E, Shanske S, Moraes CT, Silvestri G, Hirano M, et al. MELAS: Clinical features, biochemistry, and molecular genetics. Ann Neurol. 1992;31:391–8. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karkos PD, Waldron M, Johnson IJ. The MELAS syndrome. Review of the literature: The role of the otologist. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2004;29:1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.2004.00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tawankanjanachot I, Channarong NS, Phanthumchinda K. Auditory symptoms: A critical clue for diagnosis of MELAS. J Med Assoc Thai. 2005;88:1715–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pachalska M, MacQueen BD. Episodic aphasia with residual effects in a patient with progressive dementia resulting from a mitochondrial cytopathy (MELAS) Aphasiology. 2001;15:599–615. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bzoch KR, Richard L. The bzoch-league receptive-expressive emergent language scale for the measurement of language skills in infancy. In: Kenneth B, editor. Assessing Language Skills in Infancy: A Handbook for the Multidimensional Analysis of Emergent Language. Florida: Language Education Division of Computer Management Corp; 1971. pp. 43–5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enderby P, Palmer R. 2nd ed. Austin, Texas: Proed; 2007. Frenchay Dysarthria Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallender D. Springfield, Illinois: Charles C Thomas Publisher; 1979. Eating Handicaps. Illustrated Techniques for Feeding Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sue CM, Lipsett LJ, Crimmins DS, Tsang CS, Boyages SC, Presgrave CM, et al. Cochlear origin of hearing loss in MELAS syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1998;43:350–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sproule DM, Kaufmann P. Mitochondrial encephalopathy, lactic acidosis, and strokelike episodes: Basic concepts, clinical phenotype, and therapeutic management of MELAS syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1142:133–58. doi: 10.1196/annals.1444.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]