Abstract

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) is commonly seen after viral and bacterial infections, immunization, and Plasmodium falciparum (PF) malaria. Plasmodium vivax (PV) rarely causes ADEM. We report a 14-year-old female patient who presented with acute onset bilateral cerebellar ataxia and optic neuritis, 2 weeks after recovery from PV. Magnetic resonance imaging showed bilateral cerebellar hyperintensities suggestive of ADEM. No specific viral etiology was found on cerebrospinal fluid examination. Patient responded well to treatment without any sequelae. Thus, PV too is an important cause of ADEM along with PF. Two of the previously reported cases had co-infection with falciparum malaria. The only other two reported cases, as also this patient, are from Asia. A geographical or racial predisposition needs to be evaluated. Also, a possibility of post-PV delayed cerebellar ataxia, which is classically described post-PF infection, may be considered as it may be clinically, radiologically, and prognostically indistinguishable from a milder presentation of ADEM.

Keywords: Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, delayed cerebellar ataxia, malaria, Plasmodium vivax malaria

Introduction

We report a rare patient who developed cerebellar ataxia and optic neuritis following recovery from Plasmodium vivax (PV) malaria, which is usually a mild and uncomplicated disease compared to Plasmodium falciparum (PF). Furthermore, we discuss the differentials of malarial neurological manifestations and the possibility of a new variety of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM) or of post-PV delayed cerebellar ataxia (DCA).

Case Report

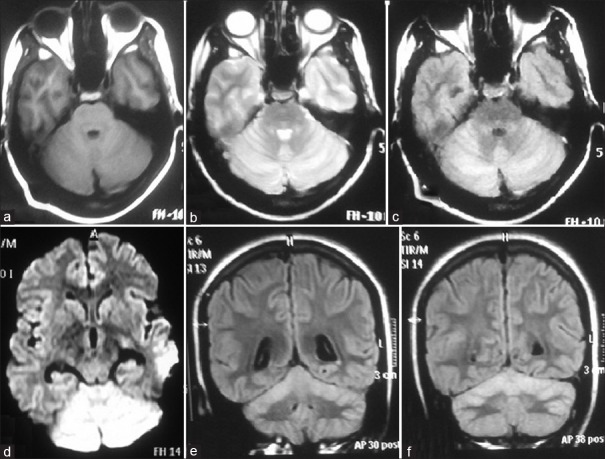

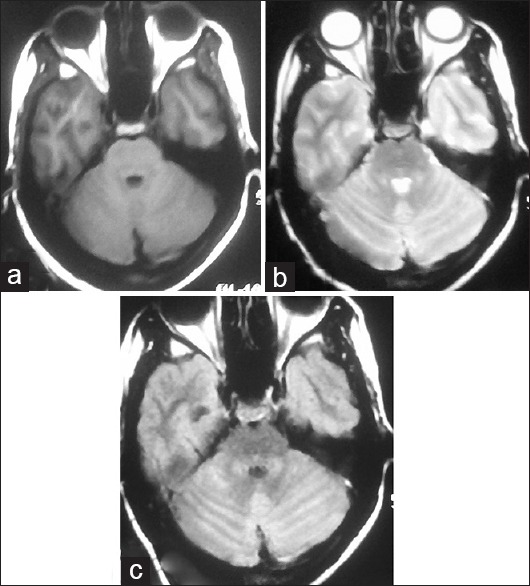

A 14-year-old female student was treated at our hospital for PV (diagnosed by slide and antigen test) with antimalarials and discharged uneventfully after 3 days. She presented to us 2 weeks later with acute gait and limb ataxia, dysarthria, and bilateral visual blurring since 2 days. She denied a history of any other symptom. She had not lost consciousness and did not report any history of seizures. There was no history suggestive of any respiratory, gastrointestinal, skin, exanthema or any other infection (except PV) in 4 weeks prior to the current symptoms. On examination, she had bilateral optic neuritis, horizontal gaze-evoked nystagmus, dysarthria, and limb and truncal ataxia. Rest examination was normal. Her complete blood count, renal and hepatic functions, blood glucose, electrolytes, human immunodeficiency virus - enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, hepatitis B and C and serological test for syphilis were normal. Malaria parasites were not seen on peripheral smear examination, and antigen test for malaria was negative. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed T1-weighted isointense and T2 and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery hyperintense signal in bilateral cerebellar hemispheres including vermis, with minimal diffusion restriction and nongadolinium enhancement [Figure 1]. MRI of the spine was normal. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) showed 65 mg/dL proteins, 10 leukocytes, 100% lymphocytes, and glucose 97 mg/dL (matching blood glucose 111 mg/dL). CSF was negative for malarial antigen test, and polymerase chain reaction for herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 and varicella-zoster virus. Other viral markers were not done due to financial constraints. CSF oligoclonal bands and serum anti-aquaporin4 antibody were negative. Visual evoked potentials showed bilaterally delayed P100. Patient was treated with Methylprednisolone 1 g/day for 5 days and began showing visual improvement by day 2 in right eye and by day 4 in left eye. Ataxia and dysarthria also improved by day 4. She was discharged on oral steroids for 6 weeks, after which follow-up examination was completely normal. Repeat MRI of the brain with gadolinium contrast after 3 months showed partial resolution of previous lesions and no new lesions [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain axial images showing bilateral cerebellar hemispheres (a) T1-weighted isointense, (b) T2-weighted hyperintense, (c) fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) hyperintense, (d) restricted diffusion on diffusion-weighted imaging sequence. (e and f) MRI brain coronal FLAIR images showing bilateral cerebellar hyperintense signals

Figure 2.

Repeat magnetic resonance imaging brain axial images after 3 months showing partial resolution of the previous hyperintense signals in bilateral cerebellar hemispheres: (a) T1-weighted image, (b) T2-weighted image, (c) fluid-attenuated inversion recovery image

Discussion

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis is an immune disease of the central nervous system occurring after an infection (93%) or immunization.[1] Histopathology reveals widespread perivenular inflammation and myelinolysis. Molecular mimicry or nonspecific activation of autoreactive T-cell clones lead to a transient autoimmune response toward myelin-oligodendrocyte antigens. Patients have obtundation, hemiparesis (76%), ataxia (59%), hypoesthesia, seizures, meningismus (26–31%) or acute polyradiculoneuropathy.[1] Many viruses, bacteria, and PF (not PV) are known to cause ADEM.[1]

The various neurological presentations of PF include cerebral malaria, postmalaria neurological syndrome (PMNS), ADEM, or DCA.[2] Cerebral malaria presents with clinical symptoms similar to ADEM but occurs during the stage of parasitemia.[1] PMNS is a self-limiting postinfective encephalopathy that occurs within 2 months after an episode of PF. DCA has been described from Sri Lanka as cerebellar ataxia occurring after an afebrile period of 3–41 days (median 13 days) after recovery from PF.[2]

Though PV is usually a milder disease compared to PF, occasional patients follow a severe course similar to PF. Previously, one case has been reported of post-PV ADEM in Japan,[3] and another of post-PV acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis.[4] Two cases of mixed PF-PV infection leading to ADEM[5] or multiple sclerosis (MS)-like[6] MRI picture have been reported, in which the role of PV apart from PF cannot be assessed, as PF commonly causes ADEM. Furthermore, the authors of one of the latter reports proposed the generalized immunosuppression due to PF, and not PV, which led to varicella-zoster induced infectious ADEM in their case.[5]

Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in children presents with fever, vomiting, headache, gait disturbances, and seizures. Overall, 29% have gait disturbances, 21% have dysarthria, and cerebellar involvement on MRI is in only 7%.[7] On repeat MRI, patients with ADEM typically have no new lesion (0–9% have new lesions) and old lesions resolve completely in 27–55% and partially in 45–64%.[8] Furthermore, simultaneous bilateral optic neuritis is more suggestive of ADEM than MS or neuromyelitis optica (NMO).[8] There are a lot of similarities between ADEM and PMNS, including the latent period from initial infection to neurological symptoms, clinical and MRI finding, response to steroids, good prognosis, and resolution of MRI findings posttreatment.[9] However, PMNS is mentioned only after severe PF, not PV. Thus, our patient was considered to have ADEM and not PMNS. DCA occurs after a median of 13 days of PF (not PV) infection, patients being alert and conscious. They respond to steroids, have a good prognosis and only one-third of them have parasitemia at presentation. Thus, it is not possible to rule out DCA in this patient other than that our patient had vivax malaria and not falciparum.[10]

In our patient, we ruled out MS and NMO. PMNS was less likely as patient had normal sensorium, and it occurs after PF infection. As CSF was negative for the tested common viruses and with a history of PV infection, a post-PV ADEM was concluded. However, a likely entity of post-PV DCA with optic neuritis as a part of its spectrum could not be ruled out. We believe that ADEM occurs more commonly after PV than previously thought. Furthermore, as our patient had symptoms 2 weeks after recovering from malaria, autoimmune mechanisms play a role rather than direct infection. A new variant of ADEM with involvement of the cerebellum and optic nerve may exist, other than the commonly described myelitic and encephalitic forms. ADEM in children presents predominantly with gait ataxia and dysarthria.[7] One highlight is that all but one of the reported cases of post-PV ADEM are from Asia. Further studies on this are needed to evaluate a geographical influence. Furthermore, we would like to consider a possibility of post-PV DCA and hope future studies may throw light on whether this entity exists.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Noorbakhsh F, Johnson RT, Emery D, Power C. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis: Clinical and pathogenesis features. Neurol Clin. 2008;26:759–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2008.03.009. ix. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Senanayake N, de Silva HJ. Delayed cerebellar ataxia complicating falciparum malaria: A clinical study of 74 patients. J Neurol. 1994;241:456–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00900965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koibuchi T, Nakamura T, Miura T, Endo T, Nakamura H, Takahashi T, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis following Plasmodium vivax malaria. J Infect Chemother. 2003;9:254–6. doi: 10.1007/s10156-003-0244-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Venugopal V, Haider M. First case report of acute hemorrhagic leukoencephalitis following Plasmodium vivax infection. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2013;31:79–81. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.108736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lademann M, Gabelin P, Lafrenz M, Wernitz C, Ehmke H, Schmitz H, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis following Plasmodium falciparum malaria caused by varicella zoster virus reactivation. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:478–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mani S, Mondal SS, Guha G, Gangopadhyay S, Pani A, Das Baksi S, et al. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis after mixed malaria infection (Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax) with MRI closely simulating multiple sclerosis. Neurologist. 2011;17:276–8. doi: 10.1097/NRL.0b013e3182173668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jayakrishnan MP, Krishnakumar P. Clinical profile of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis in children. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2010;5:111–4. doi: 10.4103/1817-1745.76098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dale RC, Branson JA. Acute disseminated encephalomyelitis or multiple sclerosis: Can the initial presentation help in establishing a correct diagnosis? Arch Dis Child. 2005;90:636–9. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.062935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohsen AH, McKendrick MW, Schmid ML, Green ST, Hadjivassiliou M, Romanowski C. Postmalaria neurological syndrome: A case of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:388–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.3.388a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Markley JD, Edmond MB. Post-malaria neurological syndrome: A case report and review of the literature. J Travel Med. 2009;16:424–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8305.2009.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]