Abstract

Guillain–Barre syndrome (GBS) is rarely reported in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and may be difficult to differentiate from vincristine induced neuropathy. Only few case reports highlighted GBS with ALL. We report a 10-year-old male child who was a diagnosed case of ALL since 3 month on chemotherapy. At 3rd week of chemotherapy, he developed rapidly progressive ascending motor quadriparesis over 2 days. Clinical and electrophysiology revealed acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN) variant of GBS. He was treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (2 g/kg) without discontinuing chemotherapy. Complete recovery took 12 weeks despite immunotherapy, and it was corroborating to slow remission. We concluded that AMAN variant is usually present in B-cell type ALL, may be causal for GBS and it takes 6–16 weeks to complete recovery which may correspond to remission of ALL. However, it needs to be studied. We also present a meta-analysis of previously reported cases of GBS in ALL.

Keywords: Acute lymphoblastic leukemia, chemotherapy, children, Guillain–Barre syndrome

Introduction

The fact that so many cases of Guillain–Barre syndrome (GBS) begin after a viral or bacterial infection suggests that certain characteristics of some viruses and bacteria may activate the immune system inappropriately. Evidence of GBS in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is very rarely highlighted. Differentiation from other neuropathies is important from the therapeutic point of view. We report a case of GBS in children on induction chemotherapy for B-cell types ALL.

Case Report

A 10-year-old boy, was investigated and diagnosed as ALL just 3 months prior for his 4 months symptoms of easy fatigability, fever, anemia and cervical lymphadenopathy. His bone marrow flow cytometry revealed 95% precursor B ALL with CD10, co-expression of CD10 and CD19 and human leukocyte antigen–DR positive, but his cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) had no blasts cells. He was kept on induction chemotherapeutic regimen according to the Medical Research Council United Kingdom Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia-12 protocol (daunorubicin 50 mg and vincristine 1.5 mg given intravenously on days 1, 8, 15 and 22, prednisolone 50 mg, once daily on days 1–28, and L-asparaginase 5000 units intramuscularly on days 17–28).

During 4th week of chemotherapy (3 days after 4th dose of vincristine) he developed rapidly progressive ascending weakness of all four limbs over 48 h without concurrent or antecedent history of infections. On examination, he had pure motor are flexic quadriplegia without involving the bladder, respiratory or bulbar muscles. Power was grade three in upper limbs and grade zero in lower limbs. Polyradiculoneuropathy was considered with differentials of GBS, vincristine induced neuropathy and precipitation of hereditary neuropathy by drugs (vincristine). Investigation revealed leukocytosis (14,300/mm3), thrombocytopenia (98,700/ml), CSF showed glucose - 53 mg/dL; protein - 128 mg/dL; cell count - 5 lymphocytes/mm3 and absent blasts cells. Contrast enhancing magnetic resonance imaging spine and brain, anti-nuclear antibody and rest were normal. Electrophysiological evaluation done on day 5 of illness revealed a pure motor axonal polyradiculoneuropathy pattern. The common peroneal and tibial nerves were bilaterally unexcitable. Bilateral median and ulnar nerves showed reduction in amplitude of compound muscle action potentials, prolonged latencies, and normal conduction velocities. F waves were absent in lower limbs with prolonged latency in nerves of upper limbs. The sensory nerve action potentials were normal in all the tested nerves. Needle electromyography showed the neurogenic pattern. Correlating the clinical and electrophysiological findings, acute motor axonal neuropathy (AMAN) – a subtype of GBS was kept.

He was treated with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) (0.4 g/kg/day) for 5 days without discontinuing chemotherapy. The weakness began to improve on the 10th day following administration of IVIG. Six weeks later, he had complete improvement in upper limbs but require assistance for walking (power grade 2–3/5). After 6 weeks, he started to achieve remission (bone marrow blast 29%), simultaneously his motor deficit also started to improve. He took total 14 weeks to achieve complete remission (bone marrow blast 5%) and 12 weeks to get full recovery in motor deficit. Unexpectedly both were achieved simultaneously. He is presently on maintenance chemotherapy. During 12th week, nerve conduction study showed normal parameter. Neither was there any finding on examination nor any family history suggestive of a hereditary neuropathy.

Discussion

Guillain–Barre syndrome is an acute, severe and fulminant, polyradiculoneuropathy that is autoimmune in nature. Electrodiagnostically they are described as demyelinating and axonal subtypes. The immunological vulnerability of the peripheral nervous system could be increased in lymphoproliferative disorders; known infective triggers could precipitate an immune neuropathy in this setting. The association between GBS and ALL could be coincidental or causal. The pathophysiologic basis for acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy (AIDP) in children with ALL remains unclear. Some evidence suggests immunosuppression secondary to intensive chemotherapy.[1] Immune system neoplasms may also act to trigger AIDP in a manner similar to some viral infections.[2]

Differentials of neuropathy in our case could be vincristine induced neuropathy, AIDP, carcinomatous infiltration, expression of hidden hereditary neuropathy during induction (vincristin) therapy. However, a high index of suspicion is needed for differentiation from other neuropathies. Vincristine induced neuropathy, is a toxic, “dying-back” neuropathy with prominent sensory involvement.[3] Vincristine may also cause a fulminant neuropathy with severe weakness in patients with hereditary neuropathy. In our case, the clinical and electrophysiological features were not supportive of vincristine induced and hereditary neuropathy.[4,5,6]

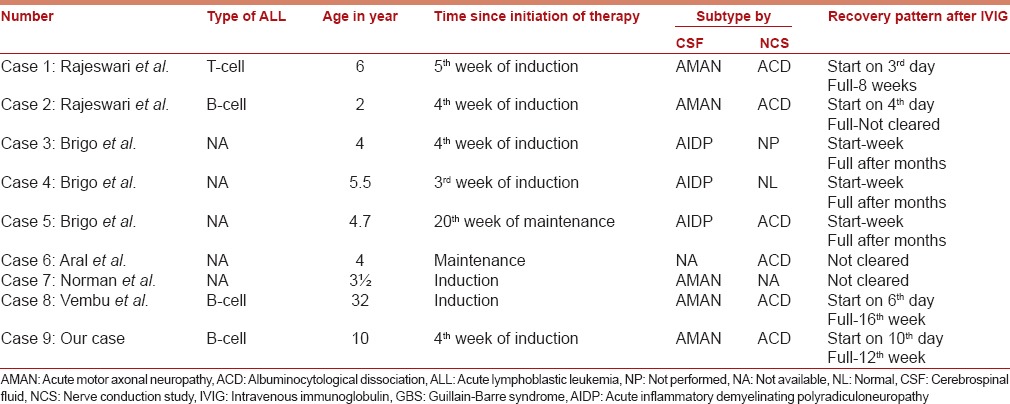

Improvement of GBS with immunotherapy, in this case (before remission of ALL) is different from other cases of GBS in an autoimmune disorder, not directly related to the hematologic malignancy. The cases so far reported, three were in the B cell type ALL and had AMAN variant.[6,7,8] Except two cases, all were described during induction therapy and onset was in 3–5 weeks of therapy. Almost all cases had albuminocytological dissociation in CSF. All responded to IVIG. All cases had vincristine in induction therapy and were continued during treatment of neuropathy. Albeit, complete improvement time were different and usually longer but association with remissions of ALL were not emphasized clearly. Longest recovery time (16 weeks) was only in one case of a 32-year-old female who was on induction therapy for ALL and developed AMAN variant of GBS like our case, but was treated successfully with two course of IVIG [Table 1]. Similar to this, our patient remained on vincristine, took longer time (12 weeks) to recover completely, however he started to show minimal response by a single course of IVIG. Complete response was simultaneous with complete remission in our case.

Table 1.

Meta-analysis of reported cases of GBS in ALL

Usually the recovery can be either complete or partial, depending on initiation of immunomodulatory therapy and axonal or demyelinating pattern in GBS setting. Although axonal degeneration takes longer time to recover, but odd aspect is unexpected temporal association of improvement with remission of ALL.

Conclusion

The differentiation between GBS and vincristine neuropathy is important to initiate timely immunomodulatory therapies for GBS and avoid unnecessary withdrawal of vincristine, which could worsen the outcome of ALL. Electrophysiological studies guide to the correct diagnosis. Recovery can take more than 6–16 weeks and corroborates to complete remission in ALL. However it needs to be studied further.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Guruprasad S Pujar, Dr. Banakar Basavaraj, Registrar, D.M. Neurology, Dr. S.N. Medical College and M.G. Hospital, Jodhpur, Rajasthan, India.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Aral YZ, Gursel T, Ozturk G, Serdaroglu A. Guillain-Barré syndrome in a child with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;18:343–6. doi: 10.1080/088800101300312618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brigo F, Balter R, Marradi P, Ferlisi M, Zaccaron A, Fiaschi A, et al. Vincristine-related neuropathy versus acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy in children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Child Neurol. 2012;27:867–74. doi: 10.1177/0883073811428379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guiheneuc P, Ginet J, Groleau JY, Rojouan J. Early phase of vincristine neuropathy in man. Electrophysiological evidence for a dying-back phenomenon, with transitory enhancement of spinal transmission of the monosynaptic reflex. J Neurol Sci. 1980;45:355–66. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(80)90179-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moudgil SS, Riggs JE. Fulminant peripheral neuropathy with severe quadriparesis associated with vincristine therapy. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:1136–8. doi: 10.1345/aph.19396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pal PK. Clinical and electrophysiological studies in vincristine induced neuropathy. Electromyogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1999;39:323–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norman M, Elinder G, Finkel Y. Vincristine neuropathy and a Guillain-Barré syndrome: A case with acute lymphatic leukemia and quadriparesis. Eur J Haematol. 1987;39:75–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1987.tb00168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rajeswari B, Krishnan S, Sarada C, Kusumakumary P. Guillain-Barre syndrome with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Indian Pediatr. 2013;50:791–2. doi: 10.1007/s13312-013-0201-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vembu P, Al-Shubaili A, Al-Khuraibet A, Kreze O, Pandita R. Guillain-Barré syndrome in a case of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. A case report. Med Princ Pract. 2003;12:272–5. doi: 10.1159/000072298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]